Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

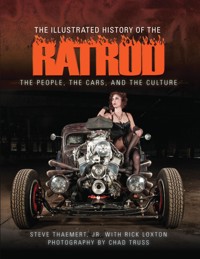

Defined by author and Rat Rod Magazine editor Steve Thaemert, Jr. as the "blue-collar hot rod," a the term "rat rod" refers to a custom car built with creativity, ingenuity, and individuality. Less of a classic-car replica and more of an expression of the builder's personality, "rat rodding" encompasses not just the vehicles but also the scene and the lifestyle ignited by this automotive hobby that's catching on like wildfire. By the editor and senior writer of Rat Rod Magazine, the comprehensive publication for all things rat rod, The Illustrated History of Rat Rod takes you inside the culture to explore the beginnings, evolution, and rising popularity of the hobby. INSIDE THE ILLUSTRATED HISTORY OF RAT ROD: •The beginnings of the rat-rod scene and early enthusiasts. •A look at the hot rods that spawned the rat-rod hobby and how the term "rat rod" was coined. •Rat Rod Magazine and its importance in defining and documenting the hobby as well as other media exposure that helped bring rat rodding into the public eye. •How rat rodding overcame opposition by detractors while gaining acceptance and supporters. •The annual Rat Rod Tour, including event results and anecdotes from attendees. •The clothes, attitudes, music, and styles that shape the rat rod culture. •A discussion of parts, building techniques, and safety practices typical of rat rodding. •A glossary of terminology unique to the rat rod hobby.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 229

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Illustrated History of the Rat Rod

Project Team

Editor: Amy Deputato

Copy Editor: Joann Woy

Design: Mary Ann Kahn

i-5 PUBLISHING, LLCTM

Chairman: David Fry

Chief Financial Officer: David Katzoff

Chief Digital Officer: Jennifer Black-Glover

Chief Marketing Officer: Beth Freeman Reynolds

Marketing Director: Cameron Triebwasser

General Manager, i-5 Press: Christopher Reggio

Art Director, i-5 Press: Mary Ann Kahn

Senior Editor, i-5 Press: Amy Deputato

Production Director: Laurie Panaggio

Production Manager: Jessica Jaensch

Copyright © 2015 by i-5 Publishing, LLCTM

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of I-5 PressTM, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thaemert, Steve, Jr.

The illustrated history of the rat rod : the people, the cars, and the

culture / Steve Thaemert, Jr. w ith Rick Loxton.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-62008-196-9 (hardback)

1. Hot rods--Customizing--History. I. Loxton, Rick. II. Title. III.

Title: Illustrated history of the ratrod.

TL236.3.T44 2015

629.228’6--dc23

2015021089

eBook ISBN: 978-1-62008-221-8

This book has been published with the intent to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter within. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the author and publisher expressly disclaim any responsibility for any errors, omissions, or adverse effects arising from the use or application of the information contained herein. The techniques and suggestions are used at the reader’s discretion and are not to be considered a substitute for veterinary care. If you suspect a medical problem, consult your veterinarian.

i-5 Publishing, LLC™

www.facebook.com/i5press

www.i5publishing.com

Introduction

There’s no question that rat rod culture is surrounded by a lot of “gray area.” For every fact, there seems to be a million opinions—opinions often formed through misperception or even bad information. And while this gray area sometimes creates confusion about what a rat rod is or where the term came from, it’s also part of the rat rod scene’s charm. Rat rods and the rat rod culture leave a lot of things open to interpretation. Some elements of the culture simply can’t be defined, while others are so subjective that they are entirely different for each person.

In this book, we’ll try to sort through the myths and get to the facts of what a rat rod is, what rat rod culture truly represents, and where this movement came from. I’ve written many articles in response to the question “what is a rat rod?” and I’ll probably write many more. It’s the question I’ve been asked most often throughout my tenure as editor of Rat Rod Magazine, and it’s the popular “pot-stirrer” in online forums. Want to get people talking? Ask them what a rat rod is. People naturally love to share their opinions, and their opinions are flavored by their own needs, ideas, and experiences.

Again, this is the charm—and possibly the biggest downer—of rat rod culture.

I’m not here to define anything. No single person or idea can do that. Only the community of builders and enthusiasts who collectively make up the rat rod scene can define exactly what a rat rod is. And even though people argue about and lobby for their own personal views on what a rat rod is, the culture tells us exactly what it is already: a rat rod is a blue-collar hot rod. Period.

Now, regarding that fact, there is a lot of room for interpretation, but the roots of rat rodding will always be deep in hot rod history. A rat rod is a form of hot rod, and the two cultures run parallel even today—maybe even more so today than in the past. The term “rat rod” may not have surfaced until the 1970s or ‘80s (no one really knows for sure), but the rat rod mentality has been around since the creation of the automobile. And, as with the automobile hobby, the terminology used in the rat rod hobby has changed over the years. What we considered a rat rod back in 1960 is much different from what we considered a rat rod in 1995, and both are much different from what we’d consider a rat rod today.

The automotive world is always evolving—cycling and recycling trends and fads, flowing alongside culture, living and dying and living again with each generation. The beauty of rat rod culture—and hot rod culture in general—is that it’s so rooted in American history that it endures. Its multigenerational appeal carries it from fathers to sons to grandsons, changing along the waybut never deviating too far from its foundations.

Preservation comes in many forms. In the automotive world, you have museum-quality restorations—which are an important part of history—all the way down to the daily driver. Yes, you can certainly drive a piece of history; in many cases, that is the best form of preservation because you are maintaining it and people are seeing the vehicle in motion in a very real way. The thing about expensive restorations is this: once you restore a vehicle, its original story is covered up forever. Take a faded ’33 Chevy sedan with all of the dents and scratches on its patina-laden body. Its story is there, in those imperfections. Maybe it has a bullet hole. Why is it there? Did it come from a couple of kids shooting targets in a field, or was this car used for a bank robbery, or … what? Patch it and paint it, and that mystery is gone. Same with old lettering or historic markings. Cover them up, and you can no longer see the story. In rat rodding, these imperfections are usually preserved. The story is left visible for each observer to interpret.

So, yes, the rat rod community is essentially preserving vehicles—albeit in an unorthodox manner. But doesn’t it make sense to leave some history alive in all of its distressed beauty? Time is an incredible artist. So is Mother Nature. They work in tandem in fascinating ways, not just on cars and trucks but on people and really everything around us. Rat rodding tends to capture that artwork and display it.

The exciting thing about today’s rat rod and hot rod scenes? You’re seeing cars from the 1930s and ‘40s and sometimes earlier that have sat for decades in scrap yards or in fields and have been resurrected and given new life. I think it’s fascinating that a seventy-five-year-old car can be patched together and driven around the country, with all of its history—its soul, if you will—preserved and passed on to a new generation. What a cool way to honor automotive history—by enjoying the very essence of the automobile: the drive itself.

Like Rat Rod Magazine has done since 2010, this book will take you on a visual journey into rat rod culture—from its roots to its modern manifestation.

Part I - Roots and History

Early Influences

The automobile. It’s hard to imagine a time when we couldn’t jump in a car or truck and head off down the road. The first legitimate steam-powered automobile was built in 1768, followed by the first car powered by an internal combustion engine in 1807. It wasn’t until 1886 that the first gasoline-powered car was produced in Germany. From there, the first production vehicles hit the market; by the early 1900s, there was an automobile boom in Europe and the United States.

Henry Ford launched the Ford Motor Company in 1903 after leaving his first company—the Detroit Automobile Company, which later became Cadillac. By 1910, gasoline-powered cars were being produced by the thousands. Rat rodding has roots here, in the “vintage era” between 1918 (the end of World War I) and 1929, when the stock market crashed. The Ford Model T was the dominant car during this time, and many of these original bodies are still used today throughout the hot rod world. While rat rods didn’t exist back then, the Great Depression of the 1930s pushed Americans into creative uses of the automobile. This “forced ingenuity” led to the birth of the “doodlebug.”

When tracing rat rod culture in search of its roots, it would be an injustice to overlook the doodlebug. Like “rat rod,” the term “doodlebug” also has its gray areas and different interpretations. The definition that’s relevant to rat rod culture describes automobiles turned into farm implements (sometimes called “doodlebug tractors”) during the material shortages and economic hardships of the Great Depression through World War II. Farmers often took their family vehicles and modified them to be used for plowing fields, hauling loads, or serving any number of purposes for which they were not originally built.

The American doodlebug is a symbol of automotive ingenuity inspired by necessity, a remnant of which lives on in today’s rat rod community. Like those who created doodlebugs in the past, rat rodders of the modern era often repurpose parts and components that are rare, broken, irreplaceable, or simply used for purposes other than those for which they were intended.

Gas Power

Karl Benz, of Mercedes-Benz lineage, produced the first gasoline-powered automobile in 1886: the Benz Patent Motorwagen.

An original 1930 Ford Model A.

The need for such functionality was very obvious during the world wars as well as during the Great Depression, but during the early automotive boom, there was also another growing element: the need for speed.

Mother Nature has programmed every living being with the drive to be better, faster, and stronger than his neighbor. Therefore, it makes sense that the invention of the automobile was followed closely by automobile racing. The earliest documented “races” were more like endurance trials to prove that these newfangled machines were capable of making it from point A to point B with a minimal amount of trouble. This was no small feat, considering that there were few roads as we know them today. Automobile owners gave no thought to modifying these early vehicles because the point was to prove their roadworthiness as-is.

Fast-forward a few decades after the automobile had become a part of everyday life for the majority of American households, and you’ll find that automobile racing had become immensely popular. The races had morphed from cross-country endurance events to competitions held on oval tracks. What had once been a hobby for the super-wealthy was now within reach of a wide audience because there was now a rich supply of old cars in junkyards to use as raw material.

The aftermarket as we know it today did not exist, so there was no available “bolt-on” horsepower to make home-built racecars go faster. In fact, people were doing just the opposite. The less weight you had to move, the faster you could go. By removing things like lights, fenders, doors, and glass, you could free up the available horsepower to move the vehicle forward with more urgency. These racecars of the common man were known as “jalopies,” and jalopy races were a mainstay of the American racing scene from the 1930s until well into the ‘60s.

Take a look at an early hot rod, and you can easily see the jalopy influence. The modern-day rat rod definitely takes cues from the old jalopy racers. The parallels are simple—low cost, do-it-yourself, vintage iron. Many people refer to rat rods as jalopies today, which is almost a slang use of the term, but somewhere in that sea of gray, the dots do connect. Doodlebug, jalopy, hot rod, rat rod … all part of the same automotive culture that was born well over a century ago.

A vintage photo from the early days of car racing.

So, where does hot rod culture begin? Rat rodding, after all, is a part of hot rod culture.

What we commonly refer to as the hot rod culture started to take off in the 1920s and ‘30s as automobiles became more common (as opposed to a luxury of the rich and privileged). The price of new cars was declining, and used cars could be found rather cheaply. Junkyards and used-car lots began to spring up, offering inexpensive entry into the fraternity of car ownership. Hot rod culture and jalopy racing are close kin, and, along with the necessity of the doodlebug, these automotive ideals all ran parallel.

Some saw the car as more than just a means to get somewhere. They saw the car as a way to explore the world, to have fun, and to express one’s self. Inspired by the popularity of automobile racing, owners began to tinker with their cars, finding ways to make them perform better, go faster, and look different from everybody else’s cars.

By the end of the 1930s, manufacturers had abandoned the “form follows function” approach to designing automobiles and began to put a lot more thought into how cars looked. They had flowing lines and graceful curves that easily lent themselves to further augmentation and customization. It is here where hot rodding began to diverge into two paths. There were those whose main goal was speed, and there were those who saw the automobile as more of a showpiece. For the latter group, everything had to be finished and shiny, and performance (outside of general “streetability”) became secondary.

A classic hot rod at on display at a vintage car show.

Above and beyond everything, the automobile represented freedom. If you had a car, the world was yours to explore. The rebel element of hot rodding was always there from the beginning. Deserted highways and dry lake beds were common gathering spots for those wanting to prove their mechanical skills and manhood by driving their modified cars faster than the rules of the road would normally allow. Adrenaline junkies—both drivers and spectators—craved the intoxicating rush of high speeds coupled with the ever-present specter of danger. Those choosing to cruise rather than race formed car clubs with aggressive-sounding names like “The Diablos” or “The Phantoms,” suggesting that their group was one to be reckoned with.

The advent of World War II put a hold on the further development of the culture as the call of duty sent a great percentage of America’s young men into the service. On top of that, everything related to automobiles was being rationed as part of the war effort. Gasoline and tires were very difficult to obtain, and there certainly wasn’t much of anything available for something as frivolous as hot rodding. America’s car manufactures even ceased the production of civilian automobiles soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, meaning that there are few 1941 models, even fewer 1942s, and no production automobiles for the years 1943, 1944, and 1945, with regular production resuming for the model year 1946.

Once soldiers began to return from duty, the hot rod culture picked up where it had left off and then exploded. Guys coming back from the war had three things that fueled this rebirth: disposable income, a plethora of new mechanical skills, and the pent-up desire to get back to doing what they loved. And then it happened: rock and roll music.

A pair of Ford coupes from 1939 and 1940 at the 2015 Lonestar Round Up show for cars from model year 1963 and earlier

The country’s youth had never had a common voice, but they found one with this exciting, albeit taboo, new music. The kids were driving mysterious-looking loud cars and listening to what was called “the devil’s music,” and the teenagers of America were indeed in full rebellion.

As auto customizers stretched their imaginations further and further, a funny thing happened. Detroit began to take notice. The cars of the late 1940s were more or less recycled designs of the late ‘30s and early ‘40s. Once manufacturers began to focus on automobile production after the end of World War II, this started to change. Of course, we were also entering the jet age and soon would be entering the space race with Russia. These two factors alone would have a great influence on the cars that would roll out of Detroit during the second half of the 1950s. But there is no denying that the creations coming out of the customizing shops and garages around the country also had an influence on what was showing up in new-car showrooms. Cars were lower and leaner—chopped and channeled from the factory. Paint schemes and interior treatments were wilder than anything that anyone had ever seen on a new car.

A highly modified custom 1951 Mercury coupe.

Pushing the Limits

Rat rodding at its basic roots is a break from the norm. It shoves its finger in the face of the hot rodding establishment and says, “I’m tired of the status quo.” It’s all part of a constantly evolving process. The original hot rods and customs were a way for people to differentiate their cars from everybody else’s. But, eventually, even those building custom cars needed to further distance themselves from the rest of the crowd. Leading the charge was a man who would become the pied piper of those everywhere who dared to be different: Ed “Big Daddy” Roth.

Roth was born in 1932 in the center of what would become the flashpoint of all things “kool” in the automotive world: Southern California. Roth immersed himself in the SoCal hot rod scene, amassing a collection of cars. His artistic nature led him to his first foray into car customization by learning how to pinstripe. This helped him make ends meet while trying to support a wife and five children by working at a department store during the day. He soon gained a reputation as a gifted pinstriper, and he eventually left the retail world behind to forge an automotive career.

The first car of Roth’s that gained significant notoriety was Little Jewel, a mildly customized 1930 Ford Model A Tudor. But it was the invention of fiberglass that cemented Big Daddy’s place in hot rodding history. This revolutionary material allowed anybody with enough mechanical know-how and determination to design and build the car of his dreams without having to learn how to perform the metalwork that was previously needed to customize a vehicle. Any design you could imagine was now within reach, and Ed’s second creation, The Outlaw, was unlike any other custom that anybody had ever seen. It caused such a buzz that he was able to open his own garage and start cranking out other mind-bending creations, including Road Agent, Mysterion, and the famous Beatnik Bandit. None of these cars (except Outlaw, for which an argument could be made that it was loosely based on a 1920s-era Ford) were based on production vehicles. They were all from the mind of Ed himself.

Kustom Kulture

The use of the term “kustom kulture” was born of Southern California roots sometime in the ‘60s and was generally used to describe the hot rod lifestyle as a whole. Although kustom kulture has evolved over the decades, it has always had an artistic and rebellious undertone. The term (and improper spelling) is still used today to describe the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s hot-rod lifestyle.

Building these cars wasn’t cheap, and much of it was financed with the airbrushed T-shirts that Ed sold at car shows. Images of his grotesque monsters, often shown piloting equally wacky custom cars, were selling just as fast as he could create them. His most popular monster was Rat Fink, which was intended to be a direct jab at the wholesome, clean-cut Mickey Mouse. Rat Fink was everything that Mickey Mouse wasn’t: bloated, dirty, smelly, and just plain ugly. The word “fink” in the character’s name was a slightly less vulgar derivation of another term used to describe someone of, let’s say, less than altruistic values. The outrage that these shirts caused only served to exponentially broaden their—and Ed’s—popularity. Model-car kits based on his creations sold by the millions at the zenith of their popularity.

Ed’s interests eventually turned to building custom motorcycles and three-wheeled “trikes,” but his initial visions helped usher in a new era of free-form car customization. Other luminaries of the day, such as Dean Jeffries, Gene Winfield, George Barris, and Darryl Starbird, also began to shift their focus from more traditional, organic designs to more fanciful, abstract creations with features such as asymmetrical pieces and bubble tops. Roth, along with Kenny Howard (better known by his nom de plume, Von Dutch) could also make a case for creating the primordial ooze that eventually evolved into what is now known as the “lowbrow” art movement.

Lowbrow Art

Lowbrow art became popular in the 1970s and referred to the pop surrealism movement that was heavily influenced by hot rod culture, punk music, and “comix” (underground, self-published comics).

What Is a Rat Rod?

We’ve traced the roots of rat rod culture back to the beginning of the automobile: from the doodlebug to the jalopy and all the way to the hot rod scene of the 1960s. But where does today’s rat rod really come from? The rat rod scene has continued to evolve and has taken on a life of its own in the twenty-first century. Today’s rat rod pays homage to the hot rod of old while bringing its own modern ingenuity and style to the table. Its charm lies in its vintage appeal and its rebellious nature.

Many different sources have claimed to have coined the term “rat rod” or have tried to pin its first usage to a certain person, publication, or club. The fact of the matter is that no one truly knows when the term was first used, how it was first used, or who used it first.

In this book, we won’t even try to track the term’s origins because that effort would be based on unverifiable resources and ultimately would result in more speculation. The early history of the term itself will remain mysterious and debatable until someone develops time travel and we can go back and figure it all out.

For the sake of factual explanation of the history of rat rod culture, we will emphatically declare that the term “rat rod” has its own unique meaning today and that wherever it originated is irrelevant. Because the term is so polarizing, and because what exactly a rat rod is or isn’t has been such a hot topic, let’s delve into a couple of previously published articles from Rat Rod Magazine.

Spectators enjoy the rat rods on display at the annual Lonestar Roundup event in Austin, Texas.

An Open Letter from the Editor

Published in Rat Rod in January 2011, this article was the magazine’s first official response to the question of “what is a rat rod?”

What Is a Rat Rod?

Before I dig into this question, let me start off with a little disclaimer: I appreciate all cars. I’m not a hater. If you’re into shiny restorations or European sports cars, so be it. I don’t understand why people get so bent out of shape about someone else’s tastes … I mean, a little harmless chiding is no big deal, but I’ve seen some pretty aggressive arguments over what kind of car scene someone is into. I myself grew up in a racing family. My dad was racing stock cars from the day I was born, so I grew accustomed to watching him slave away in the garage, trying to get the car ready for the weekends. I’ve always had a love for the classics, especially American muscle, and an appreciation for anything that looks cool or goes fast. But, yes, I do like rat rods the most, and I’ve developed a healthy respect for them and their builders. If you hate rats, you probably shouldn’t be reading a copy of Rat Rod Magazine. As a rat rod guy, and the editor of this magazine, I feel obligated to at least share my opinion with you about what I personally feel that a rat rod is. The truth of the matter is, you can ask ten different people, and they will all give you a different answer. There are a lot of people out there who will tell you matter-of-factly that a rat rod is (whatever they think it is), and some will even tell you exactly where the term originated … some folks have even tried to take credit for creating the term. Internet research will ultimately bring you to a couple of different common definitions. From Wikipedia: “A rat rod is a style of hot rod or custom car that, in most cases, imitates (or exaggerates) the early hot rods of the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s. It is not to be confused with the somewhat closely related ‘traditional’ hot rod, which is an accurate recreation or period-correct restoration of a hot rod from the same era.”

Rat rods have been aptly described as “rough around the edges.”

Or how ‘bout this definition from Fat Tony at RatRodStuff.com: “A rat rod is simply a custom car that is made for driving and hanging out with friends. Rat rods aren’t ultra-glossy show cars. Instead, a rat rod is an ‘unfinished’ street rod that is intentionally left a bit rough around the edges.” Here’s one from streetrods-online.com: “A rat rod is a newly developed name for the original hot rod style of the early 1950s. A rat rod is usually a vehicle that has had many of its non-critical parts removed. They are usually finished in primer or paints that are often period-correct. They are very often a conglomeration of parts and pieces of different makes, models, and aftermarket parts. The term ‘rat rod’ was first used by the high-dollar, show-car guys to describe the low-buck, home-built drivers. Don’t forget the roots of the hobby (street rods); it was the little guy in a garage on a budget (with help from his friends) that started it all.” Then there’s the squidoo.com definition: “A rat rod is an older car or truck that’s still roadworthy but has been stripped down to basics and then rebuilt (usually) with accessories and parts that date approximately from the same period as the original car.”

Using old truck bodies for builds is popular among rat rod enthusiasts.

Rat rodders believe in displaying the artwork of time and nature.

You get the idea. There are definitely some points that just about everyone agrees on, and then we have this massive gray area full of opinions and ideas that can range from traditional thinking to overly creative conceptualism. For the record: this magazine is a product of the entire rat rod scene, from every angle, covering all personalities, ideals, and components. What it really comes down to is the fact that a rat rod can be whatever you want it to be. You might be laughed at for building something goofy or praised for stretching the boundaries. There is a fine line between ridicule and respect, at least in the world of hot rods. The rat rod scene seems to be more accepting, more free-spirited, more rebellious, and more open to individual interpretation. My observation is this—if someone says, “Hey, you can’t do that!,” someone’s gonna do it.