Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

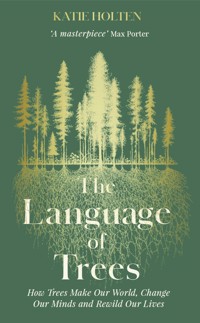

*SHORTLISTED FOR THE 2023 BRITISH BOOK DESIGN & PRODUCTION AWARDS* THE IRISH TIMES BESTSELLER and IRISH INDEPENDENT BOOK OF THE YEAR 'A masterpiece' Max Porter 'A forest of writing to be cherished' Irish Times 'One of the most inspired items of environmental literature in recent years.' Irish Independent If trees have memories, respond to stress, and communicate, what can they tell us? And will we listen? A stunning international collaboration that reveals how trees make our world, change our minds and rewild our lives – from root to branch to seed. In this beautifully illustrated collection, artist Katie Holten gifts readers her visual Tree Alphabet and uses it to masterfully translate and illuminate pieces from some of the world's most exciting writers and artists, activists and ecologists. Holten guides us on a journey from prehistoric cave paintings and creation myths to the death of a 3,500 year-old cypress tree, from Tree Clocks in Mongolia and forest fragments in the Amazon to the language of fossil poetry. In doing so, she unearths a new way of seeing the natural beauty that surrounds us and creates an urgent reminder of what could happen if we allow it to slip away. Printed in deep green ink, The Language of Trees is a celebratory homage filled with prose, poetry and art from over fifty collaborators, including Ursula K. Le Guin, Robert Macfarlane, Zadie Smith, Radiohead, Elizabeth Kolbert, Amitav Ghosh, Richard Powers, Suzanne Simard, Gaia Vince, Tacita Dean, Plato and Robin Wall Kimmerer. 'Immersive, celebratory… all beautifully illustrated.' Observer 'A visual reminder that, like strong oaks from little acorns, we still can create the world in which we wish to live.' Kerri ní Dochartaigh 'A thoughtful and incisive view of Nature across the globe.' The Countryman

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 333

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘An homage to trees in poetry, prose, and art . . . an appealing, celebratory offering with an urgent message.’KIRKUS REVIEWS

A stunning international collaboration that reveals how trees make our world, change our minds and rewild our lives – from root to branch to seed.

In this beautifully illustrated collection, artist Katie Holten gifts readers her visual Tree Alphabet and uses it to masterfully translate and illuminate pieces from some of the world’s most exciting writers and artists, activists and ecologists.

Holten guides us on a journey from prehistoric cave paintings and creation myths to the death of a 3,500-year-old cypress tree, from Tree Clocks in Mongolia and forest fragments in the Amazon to the language of fossil poetry. In doing so, she unearths a new way of seeing the natural beauty that surrounds us and creates an urgent reminder of what could happen if we allow it to slip away.

KATIE HOLTEN is an artist and activist, born in Ireland and living in New York City and Ardee, Ireland. In 2003, she represented Ireland at the Venice Biennale. She has had solo exhibitions at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, and Dublin City Gallery: The Hugh Lane. Her drawings investigate the entangled relationships between humans and the natural world. She has created Tree Alphabets, a Stone Alphabet, and a Wildflower Alphabet to share the joy she finds in her love of the more-than-human world. Her work has appeared in the Irish Times, New York Times, Artforum, and frieze. She is a visiting lecturer at the New School of the Anthropocene. If she could be a tree, she would be an Oak.

Contents

Introduction | ROSS GAY

Tree Alphabet | KATIE HOLTEN

Trees Typeface (A Rewilding Tool) | KATIE HOLTEN

SEEDS, SOIL, SAPLINGS

The Ojibwe New Year | WINONA LADUKE

He who plants a tree Plants a hope | LUCY LARCOM

Michael Hamburger | TACITA DEAN

I am the seed of the free | SOJOURNER TRUTH

Palas por Pistolas | PEDRO REYES

Acorn Bread Recipe | LUCY O’HAGAN

BUDS, BARK, BRANCHES

Oak Gall Ink Recipe | RACHAEL HAWKWIND

Branches, Leaves, Roots and Trunks | ROBERT MACFARLANE

Tree Theory, Biogeography and Branching | BRIAN J. ENQUIST

Cultivating the Courage to Sin | ANDREA BOWERS

The Wrong Trees | ZADIE SMITH

Fractal Vision | JAMES GLEICK

LEAVES & TRUNKS

It’s the Season I Often Mistake | ADA LIMÓN

from Why Information Grows | CÉSAR A. HIDALGO

Tree University | FUTUREFARMERS

from Funes, the Memorious | JORGE LUIS BORGES

Under a Plane Tree | PLATO

Fake Plastic Trees | RADIOHEAD

The Trees Breathe Out, We Breathe In | LUCHITA HURTADO

The Elm Stand | THOMAS PRINCEN

The Exact Opposite of Distance | IRENE KOPELMAN

Their Own Stories | KERRI NÍ DOCHARTAIGH

Medicine of the Tree People | VALERIE SEGREST

Blad 2 / Leaf 2 | ÅSE EG JØRGENSEN

FLOWERS & FRUITS

from Sketch of the Analytical Engine | ADA LOVELACE

An Droighneán Donn | SUSAN MCKEOWN

The Tree with the Apple Tattoo | NICOLA TWILLEY

Millenniums of Intervention | AMY HARMON

Cacao: The World Tree and Her Planetary Mission | JONATHON MILLER WEISBERGER

Tree of Life | ROZ NAYLOR

FORESTS

Two Trees Make a Forest | JESSICA J. LEE

The Word for World is Forest | URSULA K. LE GUIN

from How Forests Think | EDUARDO KOHN

from Forests | GAIA VINCE

Bewilderness | E.J. MCADAMS

from Islands on Dry Land | ELIZABETH KOLBERT

Ghost Forest | MAYA LIN

Forest | FORREST GANDERandKATIE HOLTEN

FAMILY TREES

Being | TANAYA WINDER

Brutes: Meditations on the myth of the voiceless | AMITAV GHOSH

Trophic Cascade | CAMILLE T. DUNGY

Catalpa Tree | AIMEE NEZHUKUMATATHIL

Notes for a Salmon Creek Farm Revival | FRITZ HAEG

We Are the ARK | MARY REYNOLDS

Among the Trees | CARL PHILLIPS

Mother Trees | SUZANNE SIMARD

TREE TIME

Tree Clocks and Climate Change | NICOLE DAVI

from Alphabet | INGER CHRISTENSEN

The Horse Chestnut | CHARLES GAINES

Future Library | KATIE PATERSON

Liberty Trees | ROBERT SULLIVAN

January 23, 2015 | ANDREA ZITTEL

A Matter of Time | AMY FRANCESCHINI

All the Time in the World | RACHEL SUSSMAN

TREE PEOPLE

Mujer Waorani / Waorani Women | NEMO ANDY GUIQUITA

TREE X OFFICE | NATALIE JEREMIJENKO

This is not our world with trees in it | RICHARD POWERS

I Want to Be a Tree | SUMANA ROY

What’s Happening? |

Declaration of Interbeing | KINARI WEBB

ROOTS & RESISTANCE

Why Are There No Trees in Paleolithic Cave Drawings? | WILLIAM CORWIN AND COLIN RENFREW

Speaking of Nature | ROBIN WALL KIMMERER

“Joy Is Such a Human Madness”: The Duff Between Us | ROSS GAY

Of Trees in Paint; in Teeth; in Wood; in Sheet-Iron; in Stone; in Mountains; in Stars | AENGUS WOODS

Legere and βιβλιοθήκη: The Library as Idea and Space | ANNA-SOPHIE SPRINGER

Lessons from Fungi | TOBY KIERS

They Carry Us With Them: The Great Tree Migration | CHELSEA STEINAUER-SCUDDER

AFTER TREES

Afterword: Another World is Possible | KATIE HOLTEN

Bibliography

Sources

Contributors

Acknowledgments

Colophon

Introduction

ROSS GAY

I SOMETIMES THINK OF MAKING A BOOK OF ALL THE TREES I HAVE really loved. Here’s a very incomplete list: the mulberry tree in the tiny woods between the school and the apartments where I grew up outside of Philadelphia, into which every June we’d squirrel to harvest; the chokecherry tree in Verndale, Minnesota, where my grandpa parked his hospital-green ‘68 Chevy pickup, atop which I’d scoot to pull some fruit for the both of us; the redbud tree on Third Street my partner Stephanie showed me, whose leaves, backlit late in the day, became a canopy of luminescent, blood red hearts; the pear tree at the end of the block, a sale tree from a box store that is the sweetest, most reliable fruit in town and a local oasis for human, deer, possum, yellowjackets, and more; the giant sycamore with the fleshy, oceanic bark towering in the southeast corner of the graveyard, in the shade of which on hot days is about ten degrees cooler and so is a no-brainer gathering spot; the fig tree on Christian Street in Philadelphia, between 9th and 10th; and there’s that beech tree in Vermont I met on a night hike two summers back, against whose smooth trunk I leaned my head, and though prayed isn’t quite the word, it was something like that. The beech’s breathing seemed to sync up with mine, or mine with the beech’s, and though I can’t exactly say what I was hearing, or feeling, I know it was a language coursing between us.

The word beech, I was delighted to learn a few years back, is the proto-Germanic antecedent for the English word book. The words for book in some other languages too derive from or overlap with words for trees. And though I suspect part of that common root has to do with trees providing the material for books, it’s also the case that being in a library—I mean, the best libraries—can sometimes feel like being in a forest: a wild variety of plants from the canopy to the ground; all manner of life, some of it visible, most of it not; patches of dense shade, swaths of deckled light, clearings where a huge tree just fell and you can almost hear the turning beneath, toward the light. Just as being in the forest can sometimes feel like being in a library—I mean, the best libraries—where what maybe begins as an illegible and almost foreboding place (see every fairy tale; see half of all horror movies), becomes, with time, and maybe with guidance, and patience, and wonder, all these voices, all these stories. Oh, with wonder we say, the trees have a language. There’s a language of trees.

We watch the light flickering across their leaves, or the wind blowing them into song. We see the squirrel peeking out from the porthole in the oak thirty feet up, or the yellowjackets entering and departing the withering branch which until today you would have called dead. And the bloom of fungus underneath. We enter the canopy and soften our eyes or hear or feel the thousand pollinators perusing the blooms. We reach down to pick up one in the constellation of persimmons glowing at our feet. The woodpecker and the chipmunk, the beetle and the worm. We notice the branches and all their reaching. We learn the root systems sometimes scribble through the earth far beyond their massive canopies, some of them for miles and miles and miles, entangling with other roots and life, knitted to all this other life with all this other life. Made possible by being knitted, the trees seem to be trying to tell us, to all this other life. Except the trees never say other.

What the trees say, and how they say it—the language of trees—has never been as interesting to me as it is right now. Not only because, as you now know, I have a book of beloved trees (On the first page of which is a map! Let’s figure out how to get seeds in there too! And birdsong!), not only because I have been lucky enough to work with the community orchard in my town, not only because of that beech tree whispering to me in Vermont. The language of trees is so interesting to me because whether or not we learn to understand it, or at least try to, seems so obviously, well, life or death. Our capacity and willingness to learn the language of trees, to study the language of trees, it’s so obvious to me now, might incline us to be less brutal, less extractive. It might incline us to share, to collaborate. It might incline us to give shelter and make room. The language of trees might incline us to patience. To love. It might incline us to gratitude.

Which is precisely what I would call The Language of Trees: How Trees Make Our World, Change Our Minds and Rewild Our Lives—a gratitude. A gratitude immense. Redwood gratitude. Sycamore gratitude. Aspen gratitude. Pawpaw gratitude. Not only for the gathering of wonderers and lovers of the arboreal that it brings together. But for the literal language of trees—a script made of different trees—by which it is conveyed to us. Can I tell you how batshit beautiful I find this? Can I tell you how each piece, translated into this language of trees, each essay or poem or song becoming a forest or orchard, rattles me, flummoxes me really, with how beautiful? Yes, I mean they are graphically beautiful; they are beautiful to look at as pictures, or arboreal maps or something. Like, astonishingly so. But what moves me so deeply, by which I mean into the loam, my own roots reaching out to yours, is the listening and care, the devotion and curiosity by which this script of trees comes into being. The gratitude, I mean to say, by which the language of people becomes the language of trees. The gratitude by which this book turns us into trees.

For which gratitude, I am thankful.

—Ross Gay, 2023

TREE ALPHABET

Katie Holten

TREES TYPEFACE (A REWILDING TOOL)

Katie Holten

The Ojibwe New Year

WINONA LADUKE

APRIL 16, 2022

Land determines time. Giiwedinong, or up north, we have six seasons, including a couple shorter seasons: “freeze up” and “thaw.” The Cree and Ojibwe people are the northern people here; to the west the Dene, Gwichin and Inuit have different descriptions of the seasons.

What’s for sure is that the freeze up, Gashkaadino Giizis or November in Anishinaabemowin, is called the Freezing Over Moon. March is referred to as Onaabaanigiizis, or the Hard Crusted Snow Moon.

In the Anishinaabe world, and the calendar of our people, there’s nothing about Roman emperors like Julius or Augustus. Those are not months to most of us. In an Indigenous calendar time belongs to Mother Earth, not to humans.

Bradley Robinson, from Timiskaming, Quebec, writes these seasons, not only in Cree and Ojibwe, but in syllabics, the orthography of the north:

• Ziigwan (spring): ᓰᑿᐣ

• Minookamin (the good Earth awakening): ᒥᓅᑲᒥᐣ

• Niibin (summer): ᓃᐱᐣ

• Tagwaagin (falling leaves time): ᑕ gᐚᑭᐣ

• Piiji-Piboon (on the way to winter, the freezing time): ᐲᒋᐱᐴᐣ

• Piboon (winter): ᐱᐴᐣ

If language frames your understanding of the world, those who live on the land have a different understanding than those who live in the memories of emperors. There’s no empire in creator’s time.

The Ojibwe new year has arrived.

That’s what I know. Gregorian calendars are based on commemorative times, while the Anishinaabe view the new year to begin as the world awakens after winter. Indigenous spiritual and religious practices are often said to be reaffirmation religions, reaffirming the relationship with Mother Earth.

The maple sugarbush, that’s really when the year begins, when the trees awaken. We are told that long ago, the maples ran all year, and the trees produced a sweet syrup. Our own folly changed that equation, and today the maple sap runs only in the spring, and it takes 40 gallons of sap to make a gallon of syrup.

We learned to be respectful of the gifts provided by Mother Earth. That’s a good lesson for all of us. We go to the sugarbush now, and we are grateful for the sugar which comes from a tree. This sugar is medicine.

As spring approaches, we prepare our seeds of hope, and we think about the future plants, foods and warm ahead—aabawaa, it’s getting warm out. Minookamin, the land, is warming up and with that, the geese and swans return in numbers to our lakes, thankful to be home. After that 5,000-mile flight, it seems that we could make sure their homes are in good shape, their waters clean.

I’ve been worrying about that Roundup stuff and the unpronounceable chemicals big agriculture is about to levy on these lands. I’ve always maintained that if you put stuff on your land that ends in “-cide,” whether herbicide, fungicide or pesticide, it’s going to be a problem. After all, that’s the same suffix as homicide, genocide and suicide.

Don’t eat stuff that ends with -cide. So, heading into a local Fleet Farm, or Ace Hardware, there’s going to be a lot of that in the aisles. Take Monsanto’s Roundup, that’s the stuff we are going to see all over these stores; there are thousands of lawsuits about the non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Or maybe paraquat, associated with Parkinson’s disease. An estimated 6.1 billion kilos of glyphosate-based weed killers were sprayed across gardens and fields worldwide between 2005 and 2014 (the most recent point at which data has been collected). That is more than any other herbicide, so understanding the true impact on human health is vital.

A 2016 study found a 1,000% rise in the levels of glyphosate in our urine in the past two decades—suggesting that increasing amounts of glyphosate is passing through our diet.

From the micro-plastics in our blood to the weedkiller in our urine, I’d like a little less weird stuff in my body, and maybe we move toward organic—the geese and bees like that better. That’s one of my prayers for this New Year. Along with my New Year’s resolutions: to listen better, to not lose my mittens, be with my family, and to grow more food and hemp. It’s time to make those plans.

As climate change transforms our world, I am still hoping we can keep a few constants, like our six seasons.

This is what I know, the geese return, and that’s a time. When the crows gather, the maple trees flow with sap and the world is being born again.

He who plants a treePlants a hope

LUCY LARCOM

Michael Hamburger

TACITA DEAN

MICHAEL COULDN’T BE DRAWN INTO TALKING ABOUT HIS LIFE OR HIS poetry, but was content to talk about his friend, the writer W. G. Sebald, whom Michael knew as Max. I realize now that I had quite strong feelings about how I imagined the person Sebald to be from reading his books: the German academic in self-imposed exile, plodding his rueful way down the country lanes of East Anglia, meeting, encountering, watching and remembering in the strangest of rural places, before returning home to a beautiful but run-down Norfolk home to write some of the most moving prose to come out of the twentieth century. I feel that’s what Sebald wanted us to believe he was like, especially in his book, The Rings of Saturn, because he wrote it that way. The truth is inevitably different. Max, according to Michael, was quite the opposite: a less romantic figure, anxious and obsessively tidy, courting no chaos around him as he worked, and with a restlessness of spirit that made him continue correcting his books long after they had been published. Evidently, something of the same driving dissatisfaction manifested in his work, impelling him to inexhaustible research, and to write such emotionally immense and mysteriously unquenchable books. Very clearly in The Rings of Saturn, Sebald visits the one person he would have us believe he was most like: the poet in his library in a much-loved house surrounded by piles of manila envelopes and looking out upon an English wildflower wilderness, and that person was Michael Hamburger.

Michael’s Suffolk garden was so fecund that one only had to throw an apple core out of the window and it sprung up as a tree. His orchard was cultivated in the most part from seeds, as he eschewed grafting as a method and preferred to extract the pips and plant them himself. He spent his days preserving and cultivating many varieties of apple, some long out of favor or wilfully forgotten by the commercial world. His orchard was an encyclopaedia of apples, a resource for both horticulturalist and poet.

His house had been a row of farmhand cottages, so was oddly stretched out and one room deep: you could sit looking out front and back from the same chair. The outside was unusually present inside, but of late, it had begun transgressing further, as creepers crept in under doors and around windows. Michael seemed at home with this, content to surrender to his wasteland and almost bidding it enter. He realized, he said, that he could no longer stem the tide of entropy and had begun acquiescing to old age. He had stopped planting trees, he said, because they took twelve years to bear fruit and he would no longer be around to witness it. He worried what would happen to his orchard after he died, whether it would be understood or not, and whether it would be preserved. He worried in the same way about his poetry. Michael was in spirit a harvester: a harvester of fruit as well as of words, and he has left a legacy of apples and poems.

Palas por Pistolas

PEDRO REYES

PALAS POR PISTOLAS IS A COMMISSION BY THE BOTANICAL GARDEN OF Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico. The initiative addresses two problems: the proliferation of small arms and the urgent need for reforestation.

We started a campaign calling for community members to voluntarily donate their guns. Three ads were made for a local television station, featuring different family members making the decision to give up their weapons. Thanks to private sponsors, incentives such as domestic appliances were offered in exchange for weapons at Culiacán’s City Hall. It was a record campaign with 1,527 guns collected. Forty percent were high-powered guns used exclusively by the army.

These arms were collected by the Secretaría de Defensa (Secretary of Defence) and publicly crushed with a steamroller. The wood and plastic components of the guns were removed. The crushed remnants were then taken to a foundry.

Next, they were melted to obtain the alloy that was then used to fabricate shovels. In collaboration with a major hardware factory, 1,527 shovels were made, one for every gun melted. The metal was pressed, cut, fired until red hot, forged by pressure, and then a protective finish was applied. Each handle was engraved with a legend telling the story. Through this process the weapons were made into tools, so agents of death became agents of life.

These shovels have been distributed to a number of public schools and museums where children and adults have contributed to the project of planting 1,527 trees. This ritual has a pedagogical purpose: if the violent potential of a gun can be diverted to yield positive effects on communities and the environment, so too can other aspects of society be transformed from destructive to constructive.

Several institutions in different countries have participated in Palas por Pistolas in cities such as Culiacán, Boston, Denver, Dinard, Greensboro, Guelph, London, Lyon, Marfa, Mexico City, New York, Puebla, San Diego, San Francisco, Tijuana, Vancouver, Houston, and Washington D.C.

To this day tree plantings continue, with at least one tree planted for each shovel.

Acorn Bread Recipe

LUCY O,HAGAN

FIND AN OAK TREE IN LATE AUTUMN. TOUCH THE RIDGES OF THEIR wrinkled bark and say hello. Look on the ground to see if they have dropped their seed—the deliciously smooth and chocolate brown acorn. Within each one lies the potential wisdom of a new oak tree.

Gather them in your basket, skirt or arms, and watch as the squirrels do the same. Bring them home and lay them out somewhere warm to dry completely—careful they don’t touch one another, lest the fungi take hold and consume the bunch!

Once dry, you can rattle them and hear the seed’s movement within the shell. Crack open the shell with a mortar and pestle, revealing the not-yetready-to-eat seed. This will be covered by a bitter papery membrane which needs to be removed. Rub them between a tea towel to loosen the membrane and then either peel it off with your hands or put them in a bucket of water where the membrane can float to the surface.

Now time to leach! Acorns are full of tannins—clever compounds which make them too bitter to eat straight off the tree. Grind the acorns to increase the surface area and put your grinds into a mesh bag. Now immerse this bag into flowing water which will carry off the tannins, leaving you with deliciously nutty acorn mush. Alternatively, you can boil them in a pot of water for ten minutes, strain and boil again in fresh water. Repeat this process until the water runs clear.

Dry, then toast on a pan to enhance that delicious nutty flavor and grind it into a fine flour. Hey presto, you’re now able to make your acorn bread!

Combine your acorn flour with water and salt or add honey. Form small balls with the mixture and press flat. Bake on a hot stone, roof tile or pan over the fire. Serve with blackberry jam, birch syrup or tree nuts and honey.

The wisdom of the oak now resides in your body!

Oak Gall Ink Recipe

RACHAEL HAWKWIND

OAK GALLS ARE ABNORMAL PLANT GROWTHS FOUND ON twigs on many species of oak trees, similar to benign tumors or warts in animals. They can be caused by various parasites including insects and midges. Oak galls have traditionally been used in inks and dyes because of their ability to produce rich dark blacks. This recipe can be altered to make wood stain, dye for natural fibers such as wool, silk and cashmere, and of course ink, which was in very common use for centuries. Oak gall ink was used to write the United States Declaration of Independence, U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. The tannic quality of the oak galls, which are created by insect larvae, give it its rich dark color.

INGREDIENTS

For the mordant

Rusty nails

Vinegar

Time

For the ink

20–30 oak galls

Paper bag

Water

Colander

Cheesecloth

FOR THE MORDANT

Soak rusty nails in vinegar for at least two weeks. This will create an iron mordant. A mordant, or dye fixative, is a substance used to bind dyes on fabrics.

FOR THE INK

Crush 20–30 oak galls in a paper bag.

In a large pot cover them with water and boil for at least one hour.

Strain out oak galls with a colander and then again with a cheesecloth to remove the fine particles. Add a splash of the vinegar mixture, our iron mordant.

The iron mordant is what makes the dye black and colorfast, so the longer you soak the rusty bits and the more of the solution you add, the darker your ink will be.

Return the pot to the stove and reduce further until you achieve desired consistency and color.

I have used this recipe to dye wool and most recently as a wood stain on a little cabin that I just built!

Branches, Leaves, Roots and Trunks

ROBERT MACFARLANE

THE WORD-HOARD

‘Language is fossil poetry,’ wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1844, ‘[a]s the limestone of the continent consists of infinite masses of the shells of animalcules, so language is made up of images, or tropes, which now, in their secondary use, have long ceased to remind us of their poetic origin.’ Emerson, as essayist, sought to reverse this petrification and restore the ‘poetic origin’ of words, thereby revealing the originary role of ‘nature’ in language. Considering the verb to consider, he reminds us that it comes from the Latin considerare, and thus carries a meaning of ‘to study or see with the stars’. Etymology illuminates—a mundane verb is suddenly starlit. Many of the terms in the glossaries of landscape-language that I have collected over the last decade seem, at least to me, as yet unpetrified and still vivid with poetry. They function as topograms—tiny poems that conjure scenes.

There is no single mountain language, but a range of mountain languages; no one coastal language, but a fractal of coastal languages; no lone tree language, but a forest of tree languages. To celebrate the lexis of landscape is not nostalgic, but urgent. ‘People exploit what they have merely concluded to be of value, but they defend what they love,’ writes the American essayist and farmer Wendell Berry, ‘and to defend what we love we need a particularising language, for we love what we particularly know.’

We are and always have been name-callers, christeners. Words are grained into our landscapes, and landscapes grained into our words. ‘Every language is an old-growth forest of the mind,’ in Wade Davis’s memorable phrase. We see in words: in webs of words, wefts of words, woods of words. The roots of individual words reach out and intermesh, their stems lean and criss-cross, and their outgrowths branch and clasp.

‘I want my writing to bring people not just to think of “trees” as they mostly do now,’ wrote Roger Deakin in a notebook that was discovered after his early death, ‘but of each individual tree, and each kind of tree.’ John Muir, spending his first summer working as a shepherd among the pines of the Sierra Nevada in California, reflected in his journal that ‘Every tree calls for special admiration. I have been making many sketches and regret that I cannot draw every needle.’

I have come to understand that although place-words are being lost, they are also being created. Nature is dynamic, and so is language. Loanwords from Chinese, Urdu, Korean, Portugese and Yiddish are right now being used to describe the landscapes of Britain and Ireland; portmanteaus and neologisms are constantly in manufacture. As I travelled I met new words as well as salvaging old ones: a painter in the Hebrides who used landskein to refer to the braid of blue horizon lines in hill country on a hazy day; a five-year-old girl who concocted honeyfur to describe the soft seeds of grasses held in the fingers.

BRANCHES, LEAVES, ROOTS AND TRUNKS

atchorn

acorn (Herefordshire)

balkcut

tree (Kent)

bannut-tree

walnut tree (Herefordshire)

beilleag

bark of a birch tree (Gaelic)

biests

wen-like protuberances on growing trees (East Anglia)

bole

main part of the trunk of a tree before it separates into branches (forestry)

bolling

permanent trunk left behind after pollarding (pronounced to rhyme with ‘rolling’) (forestry)

brattling

sloppings from felled trees (Northamptonshire)

breakneck, brokeneck

tree whose main stem has been snapped by the wind (forestry)

browse line

level above which large herbivores cannot browse woodland foliage (forestry)

burr

excrescence on base of tree: some broad-leaved trees with a burr, especially walnut, can be very valuable, the burr being prized for its internal patterning (forestry)

butt

lower part of the trunk of a tree (forestry)

cag

stump of a branch protruding from the tree (Herefordshire)

cant-mark

stub pollarded tree used to mark a land boundary (forestry)

celynnoga

bounding in holly (place-name element) (Welsh)

chats

dead sticks (Herefordshire)

chissom

first shoots of a newly cut coppice (Cotswolds)

cramble

boughs or branches of crooked and angular growth, used for craft or firewood (Yorkshire)

crank

dead branch of a tree (Cotswolds)

crìonach

rotten tree; brushwood (Gaelic)

daddock

dead wood (Herefordshire)

damage cycle

narrower rings in the stump of the tree, indicating the accidental loss of branches which are gradually replaced. Useful in helping to work out when and at what intervals a tree has been pollarded/coppiced (forestry)

deadfall

dead branch that falls from a tree as a result of wind or its own weight (forestry)

dodderold

pollard (Bedfordshire)

dosraich

abundance of branches (Gaelic)

dotard

decaying oak or sizeable single tree (Northamptonshire)

eirytall

clean-grown sapling (Cotswolds)

eller

nelder tree (Herefordshire)

flippety

young twig or branch that bends before a hook or clippers (Exmoor)

foxed

term applied to an old oak tree, when the centre becomes red and indicates decay (Northamptonshire)

frail

leaf skeleton (Banffshire)

griggles

small apples left on the tree (south-west England)

interarboration

intermixture of the branches of trees on opposite sides (used by Sir Thomas Browne in The Garden of Cyrus, 1658) (arboreal)

kosh

branch (Anglo-Romani)

lammas

second flush of growth in late summer by some species, e.g. oak (forestry)

leafmeal

tree’s ‘cast self,’ disintegrating as fallen leaves (Gerard Manley Hopkins) (poetic)

lenticels

small pore in bark or a leaf for breathing (forestry)

maiden

tree which is not a coppice stool nor a pollard (forestry)

mute

stumps of trees and bushes left in the ground after felling (Exmoor)

nape

when laying a hedge, to cut the branch partly through so that it can be bent down (East Anglia)

nubbin

stump of a tree after the trunk has been felled (Northamptonshire)

palmate

leaves that have lobes arranged like the fingers of a hand, e.g. horse chestnut (forestry)

pankto

knock or shake down apples from the tree (Herefordshire)

pollard

tree cut at eight or twelve feet above ground and allowed to grow again to produce successive crops of wood (forestry)

raaga tree

tree that has been torn up by the roots and drifted by the sea (Shetland)

rammel

small branches or twigs, especially from trees which have been felled and trimmed (Scots)

rootplate

shallow layer of radially arranged roots revealed when a tree has blown over (forestry)

rundle

hollow pollard tree (Herefordshire)

scocker

rift in an oak tree caused either by lightning blast or the expansive freezing of water that has soaked down into the heart-wood from an unsound part in the head of the tree (East Anglia)

scrog

stunted bush (northern England, Scotland)

slive

rough edge of a tree stump (northern England, Warwickshire)

spronky

of a plant or tree: having many roots (Kent)

staghead

dead crown of a veteran tree (forestry)

starveling

ailing tree (forestry)

stool

permanent base of a coppiced tree (forestry)

suthering

noise of the wind through the trees (John Clare) (poetic)

tod

stump of a tree sawn off and left in the ground; the top of a pollard tree (Suffollk)

wash-boughs

straggling lower branches of a tree (Suffolk)

wewire

to move about as foliage does in wind (Essex)

whip

thin tree with a very small crown reaching into the upper canopy (forestry)

wolf

bigger than average tree which is dominant in the crop, often removed at first thinning (forestry)

Tree Theory, Biogeography and Branching

BRIAN J. ENQUIST

EVERYONE KNOWS MORE OR LESS WHAT A TREE LOOKS LIKE. Although the architecture of any two trees across the world may at first look very diverse, analysis of the mathematics of branching shows a different story. We now know that the diversity of tree architecture can be generated by very simple and common rules across all plants—if not all of life, including animals. These rules basically govern not only how trees branch and when they branch but also the sizes and shapes of those branches, as well as the structure and functioning of forests across the globe.

Understanding these branching rules has allowed us, as scientists, to make accurate predictions about how plants and even whole forests work—in particular how they flux carbon dioxide. If you know something about the branching network, you can make predictions about the entire plant’s functioning. Then you can extend that to understand the ecology of the forest.

The rules appear both in the external branching architecture, or how the branches are arranged, and in the internal structure of the tissues that transport nutrients throughout the tree.

The study of plant architecture has revealed two important yet disparate viewpoints about the evolutionary origin of plant branching patterns. On the one hand, plant architecture often reflects differences in specific growth environments and taxon-specific selection on allocation and life history. Indeed, diverse architectural branching designs that exist in nature as well as specific genes that regulate growth and development often match differences in architecture. On the other hand, categorizing the diversity of plants has sometimes focused on similarities in the patterns of branching and the scaling of branch dimensions, such as number, radius, and length.

Perhaps the most significant insight about the math of real trees comes from Leonardo da Vinci’s original observation of tree construction. He noted that ‘all the branches of a tree at every stage of its height, when put together, are equal in thickness to the trunk below them’. We call this branching rule ‘area-preserving’. Take any mother branch and its daughter branches—the cross sectional area of the mother branch will equal the total cross sectional area of the daughter branches. This was an amazing insight—the total cross-sectional area of the twigs of a tree will be approximately equal to the cross-sectional area of the main trunk. We have used Leonardo’s ‘area-preserving’ as a basis for understanding the structural and functional design of trees. We have come to know that area preserving reflects evolution by natural selection for optimal branching networks. Area-preserving ensures that a tree is biomechanically stable (it will resist gravity better and be less prone to being knocked down). Further, area-preserving networks are more efficient at transporting resources (water and sugar) within their vascular systems.

We can break down tree architecture into a handful of rules. For a branch of a given size: ‘Grow so much and then branch, and then grow so much and then branch.’ This rule governs what the dimensions of the branches have to be. That is, ‘grow until your branch is such and so much length, or so much in width’. Repeating this rule as a plant grows results in a tremendously complicated but beautiful form such as a tree and ultimately it stems down to a very efficient code.

This rule or code can be described mathematically and can be seen to reoccur as the tree grows, creating a fractal—a repeating pattern—like a spiral of daughter branches emanating from the mother branch or tree trunk. These branching rules hold true across species, so the ratios of lengths and radii of a mother branch to daughter branches are similar for almost all trees. But palm trees don’t count: That’s basically one big branch with a bunch of leaves at the end.

There are additional branching rules that can also kick in. You can still follow these basic branching rules of radii and lengths, but if you change the angles at which they branch this will result in a tremendously different looking tree.

So why do these rules exist in the first place? We have proposed that all tree architectures are the result of natural selection acting on the scaling of resource uptake and resource distribution. Our theory predicts that whole-plant carbon and water fluxes, net primary production, and population density should also be characterized by similar scaling functions. Natural selection would select for shapes of trees that, as they grow from seedling to adult plant, solve two important problems: taking in as much resources such as light, water and nutrients as possible, while transporting resources within the plant with as little work as possible.

There are these two conflicting evolutionary pressures on the architectures of trees. In biology we call this a trade-off. For plants the question is how to get food, or resources, with as little work as possible. Work is transporting nutrients and water through internal tissues called xylem and phloem, and the less energy they have to expend to transport nutrients, the more they have for growth and reproduction. Ultimately, natural selection has fine-tuned the rules that govern plants’ internal and external frameworks to a simple repeating pattern coded for by their DNA. The external branching network governs a plant’s shape, which determines the number of leaves on a tree, which then also influences how much carbon is fluxed within the tree.

Biology is basically all about trees. It turns out that the organization and design of biological networks are all around us. We have cardiovascular systems, we have neural systems, we have plant vascular networks. Biological trees are built around common themes in the geometry of vascular networks. Vascular networks flux resources, and resources are basically what maintain us. The speed at which you’re able to flux resources will then influence the speed of your physiology: How fast you grow, how long it will take you to reach reproductive maturity, how long ultimately organisms live. In the case of trees, how much carbon dioxide they are able to absorb from the atmosphere. If you understand the organization of vascular networks you can actually predict an enormous amount about the functioning of organisms.

Because nearly all plants grow by the same network rules, we can scale up these rules to make accurate predictions about the functioning of an entire forest. In a forest, where resources such as sunlight and water are limited, trees compete with each other to get as much of what they need to live and grow as possible. The result is a fractal-like filling of the forest space, with a few large trees taking up most of the resources and many small trees filling in the cracks. The ratio of big trees to little trees in a forest turns out to be the same as the ratio of big branches to little branches on a single tree from that forest. From this we can determine many aspects of how entire forests work. If we know something about these branching rules we can start saying something about what may happen in the future. These branching patterns are so prevalent that they will govern and influence how plants respond in a changing world.

Tausende von E-Books und Hörbücher

Ihre Zahl wächst ständig und Sie haben eine Fixpreisgarantie.

Sie haben über uns geschrieben: