11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

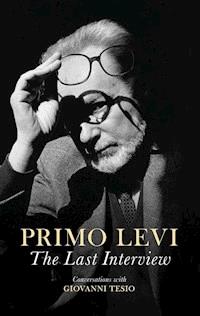

At the start of 1987, Primo Levi took part in a remarkable series of conversations about his early life with a friend and fellow writer, Giovanni Tesio. This book is the result of those meetings, originally intended to be the basis for an authorized biography and published here in English for the first time.

In a densely packed dialogue, Levi responds to Tesio’s tactful and never too insistent questions with a watchful readiness and candour, breaking through the reserve of his public persona to allow a more intimate self to emerge. Following the thread of memory, he lucidly discusses his family, his childhood, his education during the Fascist period, his adolescent friendships, his reading, his shyness and his passion for mountaineering, and recounts his wartime experience as a partisan and the terrible price it exacted from him and his comrades. Though we glimpse his later life as a writer, the story breaks off just before his deportation to Auschwitz owing to his sudden death.

In

The Last Interview, Levi the man, the witness, the chemist and the writer all unite to offer us a story which is also a window onto history. These conversations shed new light on Levi’s life and will appeal to the many readers of this most eloquent witness to the horrors of the Holocaust.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 174

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title page

Copyright page

Introduction

Notes

I knew Primo Levi

Notes

Acknowledgements

Monday, 12 January

Notes

Monday, 26 January

Notes

Sunday, 8 February

Notes

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Start Reading

Pages

iv

vi

viii

xii

vii

ix

x

xi

xiii

xix

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xx

1

2

4

7

9

17

19

22

23

28

29

32

33

36

37

39

41

42

3

5

6

8

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

18

20

21

24

25

26

27

30

31

34

35

38

40

43

44

45

51

56

64

68

69

72

73

74

78

80

81

84

46

47

48

49

50

52

53

54

55

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

65

66

67

70

71

75

76

77

79

82

83

85

86

87

88

89

92

93

95

97

98

99

102

104

106

108

112

113

115

116

117

118

121

124

125

126

128

129

130

90

91

94

96

100

101

103

105

107

109

110

111

114

119

120

122

123

127

Copyright page

First published in Italian as Io che vi parlo. Conversazione con Giovanni Tesio © Giulio Einaudi editore s.p.a, Turin, 2016

This English edition © Polity Press, 2018

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1954-5

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1955-2 (pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Levi, Primo, author. | Tesio, Giovanni, 1946- interviewer.

Title: The last interview : conversation with Giovanni Tesio / Primo Levi.

Other titles: Lo che vi parlo. English

Description: Medford, MA : Polity, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017058561 (print) | LCCN 2017059366 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509519583 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509519545 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509519552 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Levi, Primo–Interviews. | Authors, Italian–20th century–Interviews. | Jewish authors–Italy–Interviews. | Holocaust survivors–Italy–Interviews.

Classification: LCC PQ4872.E8 (ebook) | LCC PQ4872.E8 Z4613 2018 (print) | DDC 858/.91409–dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017058561

Typeset in 11 on 14 pt Sabon by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by Clays Ltd, St Ives PLC

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Introduction

The conversations in this book were intended as material for an authorized biography, but they were also an act of kindness. The literary critic Giovanni Tesio had realized that his friend Primo Levi was suffering from severe depression which left him feeling unable to write, and thought that working together in this way might be consoling and even therapeutic. Consequently these transcriptions are in one sense an intimate record of life events shared with a friend, but in another and very important sense they enable us to overhear the words of a very reserved and private man who paradoxically used his own experiences as the basis for his greatest work.

There are good reasons for Levi's desire to keep his home life out of the public sphere. Turin, his native city, was proverbially reserved and respectful of the proprieties, and his upbringing there was a typically bourgeois one. For a young man from such a background, one of the most devastating aspects of the barbarities he suffered in Auschwitz was that, along with their clothes and their hair and even their names, prisoners were stripped of every last shred of privacy, a degrading and depersonalizing process which began in the cattle trucks, devoid of so much as a bucket, in which deportees were transported to brief slavery or immediate death. The impulse, as he shouldered the life-long task of bearing witness, to close the front door of 75 Corso Re Umberto on a protected space, must have been overwhelming. In addition, his growing international renown, which reached its peak with the English translation, in 1984, of The Periodic Table, meant that he came to be seen, much against his will, as some kind of guru or secular saint, whose Holocaust accounts were thought to represent not a grim and needed warning but a triumph of the human spirit. As he told Tesio, he felt ‘gradually overwhelmed, first in Italy and then abroad, by this wave of success which has profoundly affected my equilibrium and put me in the shoes of someone I am not’. From this, too, the private space with which he was able to surround himself at his writing desk, as he had earlier done at his laboratory bench in the Siva paint and varnish factory, offered a much-needed retreat.

While it was Auschwitz, from which he returned ‘like Coleridge's Ancient Mariner, who waylays on the street the wedding guests going to the feast, inflicting on them the story of his misfortune’,1 which first compelled him to write about what he had suffered, observed and, exceptionally, survived, Levi was also to become a witness of a very different kind, attempting with considerable success to bridge the needless gulf which separates the so-called two cultures with dispatches from the world of pure and applied chemistry. This book should be read alongside The Periodic Table, to which it adds valuable background material about his schooldays and his emotional life as a young man, but to understand why sharing the pleasures and pains of a chemist's trade was so important to Levi, it is necessary to go into a little detail about the educational system in Italy during the Fascist period.

It is well known that Levi narrowly escaped being excluded from a university education by the passing of the anti-Semitic racial laws, and was prevented by them from going on to the academic career which, as a student who had graduated with top marks and distinction, would otherwise have been open to him. However, the frustration he felt as a schoolboy, with the narrowly arts-based curriculum which forced him to discover science through his own reading and his experiments with household chemicals, was also due to Fascist policy. As Martin Clark explains, ‘the Fascists inherited a “three-stream” system of secondary education: the ginnasio and liceo [lower and higher secondary schools] for the social élite, the technical schools and technical institutes for the commercial middle classes, and the scuole normali for girls wanting to become primary teachers … The Fascists soon changed all that. In 1923, Giovanni Gentile, as minister of education, reorganized secondary education.’ Under these reforms, initiated as they were by an idealist philosopher, the old technical schools were abolished and ‘access to, and the status of, the technical institutes was greatly reduced, as was admission to the university science faculties’. One curious effect of this reorganization was that ‘Latin, Italian, History and Philosophy were taught by men, whereas Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry continued to be taught by women. This was an apt comment on Fascist male chauvinism’, and it is an apt comment too on how the subjects which mattered most to Levi were now regarded. Another effect was that ‘Italy produced fewer engineers, scientists and doctors in the late 1930s than the early 1920s.’2 Access to higher education was now largely dependent on attending a liceo classico such as the Massimo D’Azeglio school, where Levi endured rather than enjoyed a syllabus based on those prestige subjects, turning him into a passionate advocate for the integrated culture which was shared by ‘Empedocles, Dante, Leonardo, Galileo, Descartes, Goethe and Einstein, the anonymous builders of the Gothic cathedrals and Michelangelo’ and is still shared by ‘the good craftsmen of today, or the physicists hesitating on the brink of the unknowable’.3

However, the most significant and moving revelation in The Last Interview does not concern either education or chemistry. Although Tesio suggests in his preface, ‘I knew Primo Levi’, that ‘the real difference in our conversations, as compared with other interviews, was more in the tone than the content’, in one painful respect Levi confided something to him which stitches together the repeated but oblique references throughout his writing to a ‘woman who was dear to my heart’ who had been deported to Auschwitz with him.4 That woman was Vanda Maestro, a close friend and fellow partisan, and Levi reveals to Tesio that he had been in love with her but had felt too shy and inhibited fully to reveal his feelings. He had returned from Auschwitz already knowing how she had died: ‘her name pronounced among those of the condemned, her descent from the bunk of the infirmary, her setting off (in full consciousness!) towards the gas chamber and the cremation oven’,5 and was tormented by the irrational but inevitable feeling that if only he had acted differently perhaps he and she might have been elsewhere when their partisan band was rounded up. ‘It was a really desperate situation for me, being in love with someone who was gone and, what's more, whose death one had caused, and I think that what one feels is … Perhaps if I had been less inhibited with her, if we had run away together, if we had made love … I was incapable of those things.’

Tesio at one point suggests to Levi that his writing is characterized by ‘a sort of holding back’, and Levi himself, when asked why he has written so little about the Fossoli internment camp, repeats three times, ‘ho delle remore’ [I have qualms], adding ‘And also about that woman I told you of’. A remora is a qualm, a hesitation, a scruple, an impediment, but Levi would have known that it is also the name of a family of fish, the Echeneidae or suckerfish, which in classical mythology were believed to be able to hold back any ship they attached themselves to. All this adds an extra poignancy to Levi's poem ‘Il tramonto di Fossoli’ [Sunset at Fossoli],6 dated 7 February 1946, in which he translates the famous lines from Catullus's Poem V:

soles occidere et redire possunt;

nobis cum semel occidit brevis lux,

nox est perpetua una dormienda.

[suns can set and rise again;

but we, when our brief light has set,

will have an endless night to sleep.]

The rest of Catullus's poem urges living and loving, and the exchange of countless kisses, as the best antidote to the fear of death, but Levi describes remembering these lines as he looks at the sunset through the barbed wire of the internment camp and feeling them lacerate his flesh. As in The Periodic Table, he also tells Tesio of the euphoria of falling instantly in love with his future wife, a life-changing encounter, celebrated in a poem written only four days after ‘Sunset at Fossoli’ and titled ‘11 February 1946’,7 which ‘exorcized the name and face of the woman who had gone down into the lower depths with me and had not returned’,8 but Vanda is constantly in his mind as he talks about his early life.

The Italian title of this book, Io che vi parlo, literally means ‘I who am speaking to you’, neatly, if rather untranslatably, putting the emphasis on the first person and the speaking voice. Polity Press has chosen instead to give the English edition a title which not only reflects the fact that Levi's conversations with Tesio were among the final interviews which he gave at the end of his life, but also hauntingly underlines what the final sentence of Tesio's preface makes movingly clear. Levi's last interview was the one which didn't happen: he was just about to ‘resume the work’ of telling Tesio his life story when his life came to its sudden and tragic end. This does not mean that these conversations should be scrutinized for clues or premonitions, not least because the true circumstances of Levi's death will never be known: there is no witness and no suicide note to tell us whether it was caused by a momentary blackout as he leaned over the banisters or the different blackness of a moment of overwhelming despair, and perhaps we should cease to speculate and leave him that final privacy. Although critics and biographers all too often try to shape their narratives by beginning Levi's story at its end, the manner of his death does not give us the measure of the man, or of a lifetime spent in the service both of chemistry, which as he told Tesio he saw as fundamental to everything from ‘the starry sky’ to the smallest gnat, and of human liberty, which he defended to the limits of his strength on behalf of us all.

Judith Woolf

Notes

1

Primo Levi,

The Periodic Table

, trans. Raymond Rosenthal, London: Michael Joseph, 1985, p. 151. All notes in the text are the translator's, unless marked GT (Giovanni Tesio).

2

Martin Clark,

Modern Italy: 1871–1995

, London and New York: Longman, 1996, pp. 276–7.

3

Primo Levi,

Other People's Trades

, trans. Raymond Rosenthal, London: Michael Joseph, 1989, p. viii.

4

The Periodic Table

, op. cit., p. 151.

5

‘Testimony for a fellow prisoner’, in Primo Levi and Leonardo De Benedetti,

Auschwitz Testimonies: 1945–1986

, trans. Judith Woolf, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017, p. 64. This is the concluding passage of a moving tribute to Vanda Maestro, originally published anonymously in a book in memory of Piedmontese women partisans,

Donne piemontesi nella lotta di liberazione

[Piedmontese Women in the Struggle for Liberation], printed in 1953.

6

Primo Levi,

Collected Poems

, trans. Ruth Feldman and Brian Swann, London: Faber, 1992, p. 15.

7

Collected Poems

, op. cit., p. 16.

8

The Periodic Table

, op. cit., p. 153.

I knew Primo Levi

Creating a space for conversation requires the efforts of an alpinist.

Osip Mandelštam, Conversation about Dante

‘Do you already have a plan of attack in mind?’ I was asked this question in the study of an apartment on the third floor of 75 Corso Re Umberto – one of the most elegant streets in Turin – on the afternoon of 12 January 1987.

Asking it was one of the most pacific writers to have crossed, not only in a literary sense, our twentieth-century stage, one of the most authoritative witnesses to Auschwitz, a man of undoubted integrity but just as undoubtedly wounded in spirit and flesh: a master of secularism and reason, of doubt and questioning, but also of clarity and resistance, of resolve and action.

In the austerely spacious study, in that house which resembled ‘many other quasi-patrician houses of the turn of the century’ (as he wrote in an account later published in Other People's Trades),9 Primo Levi asked me that entirely predictable question, which nonetheless disconcerted me. But to account both for the predictability of the question and for my astonishment at hearing it put to me, I need to give some preliminary explanation.

I first encountered Primo Levi by reading If This is a Man in the Einaudi ‘Corallo’ edition in 1967. And ten years later I got to know him in person, because leafing through a school anthology devoted to Piedmontese writers,10 I discovered that the pages chosen by the editor did not correspond in the least with my enduring memory of the text of If This is a Man in the edition I had read. Having compared them, I was able to discover that there existed a text previous to the Einaudi edition, and that this text had been published in 1947 by the De Silva publishing house which Franco Antonicelli, one of the leading figures in Turinese anti-fascism, had founded in ’42 and which had closed down in ’49. Comparing the De Silva text with the first Einaudi edition of 1958, which has remained identical in subsequent reprintings, I then discovered that the variants were neither few nor insignificant. So I plucked up my courage (in Piedmontese there is a fine saying, to put on a ‘bon bèch’, which literally means a ‘good beak’) and telephoned the author, who without hesitation invited me to his house and put at my disposal an exercise book: a thick school exercise book with an olive green cover, in which I was able to check the text of the parts which had been added. And so I wrote an article,11 in truth rather hybrid and certainly not perfect (I did not take account of the chapters already published thanks to Silvio Ortona in the Vercellese Communist journal L’Amico del Popolo [The Friend of the People]), but which all the same had a modest success.

After this, I returned to question Levi again about the problem of variants. And it was he who allowed me to look not only at the handwritten exercise book in which he had composed nearly all the chapters of The Truce, but – in due course – at the typescript of The Wrench prepared for publication, which took place in ’78. So I could be quite sure that he was referring to me when, with the arrival of the computer, he wrote an article called ‘The Scribe’ for La Stampa (later collected in Other People's Trades), in which he talks about a ‘literary friend’ who laments the loss of ‘the noble joy of the philologist intent on reconstructing, through successive erasures and corrections, the itinerary which leads to the perfection of the Infinite’.12

After that first piece of work, others followed. First of all a ‘critical portrait’ published in Belfagor13 two years later. And then quite a number of reviews and interviews. So that when he was thinking of publishing the poems of Ad Ora Incerta [At an Uncertain Hour], he consulted me – it was the time when Einaudi was going through its most acute crisis, which saw the diaspora of other writers, for example Lalla Romano, who published Nei mari estremi [The Furthest Seas] with Mondadori – about finding another possible and worthy publisher, and I suggested that he should consider Garzanti, as in fact he did.

Levi was unassuming, sober, discreet and very courteous. And I was fascinated not only by the expressive precision of his books, by his wide-ranging and detailed knowledge, by his remarkable memory, but also by his receptiveness and his undoubted and special ability to communicate with precise and succinct words, in which all the same there vibrated a note which was not without some trace of melancholy: that ability of his to avoid all superfluities and to base his writing instead on a rich and ornate sobriety of language, on the plain elegance of the mot-chose.

To have got to know Levi also means this: recognizing in his written words the grain of his speaking voice: anti-rhetorical but not inert, familiar but almost festive, a monotone which was capable of expressive power.

There grew up between us something that was more than mere civility. So much so as to permit us to address each other as tu rather than lei14