Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Irving's extensive work on Christopher Columbus is one of the most famous biographies in American history. The name of Washington Irving, prefixed to any work, is in itself a sufficient earnest of liberal sentiment and graceful composition. With generous principles and pure intellectual tastes, he unquestionably unites literary talents of no common order. The subject, also, which he has here chosen for the exercise of his powers, is one, if not of any real novelty, at least abounding both in romantic excitement and philosophical interest. It is a subject in many respects, congenial to his own poetical cast of feeling, his imaginative temperament, his amiable and enlightened spirit, and, above all, to his national enthusiasm as a citizen of that continent, of which the discovery has immortalised the fame of his hero. Endowed with such qualifications, and thus inspired by characteristic fondness for his design, it was easy to anticipate the degree of his success in its accomplishment; and it is needless to say, that he has produced a very amusing and elegant book.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1590

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Life And Voyages OfChristopher Columbus

Washington Irving

Contents:

Washington Irving – A Biographical Primer

The Life And Voyages Of Christopher Columbus

Preface.

Book I.

Chapter I. Birth, Parentage, And Early Life Of Columbus.

Chapter Ii. Early Voyages Of Columbus.

Chapter Iii. Progress Of Discovery Under Prince Henry Of Portugal.

Chapter Iv. Residence Of Columbus At Lisbon Ideas Concerning Islands In The Ocean.

Chapter V. Grounds On Which Columbus Founded His Belief Of The Existence Of Undiscovered Lands In The West.

Chapter Vi. Correspondence Of Columbus With Paulo Toscanelli - Events In Portugal Relative To Discoveries - Proposition Of Columbus To The Portuguese Court Departure From Portugal.

Book Ii.

Chapter I. Proceedings Of Columbus After Leaving Portugal His Applications In Spain Characters Of Ferdinand And Isabella.

Chapter Ii. Columbus At The Court Of Spain.

Chapter Iii. Columbus Before The Council At Salamanca.

Chapter Iv. Further Applications At The Court Of Castile - Columbus Follows The Court In Its Campaigns.

Chapter V. Columbus At The Convent Of La Rabida.

Chapter Vi. Application To The Court At The Time Of The Surrender Of Granada.

Chapter Vii. Arrangement With The Spanish Sovereigns - Preparations For The Expedition At The Port Of Palos.

Chapter Viii. Columbus At The Port Of Palos - Preparations For The Voyage Of Discovery.

Book Iii.

Chapter I. Departure Of Columbus On His First Voyage.

Chapter Ii. Continuation Of The Voyage First Notice Of The Variation Of The Needle.

Chapter Iii. Continuation Of The Voyage Various Terrors Of The Seamen.

Chapter Iv. Continuation Of The Voyage - Discovery Of Land.

Book Iv.

Chapter I. First Landing Of Columbus In The New World.

Chapter Ii. Cruise Among The Bahama Islands.

Chapter Iii. Discovery And Coasting Of Cuba.

Chapter Iv. Further Coasting Of Cuba.

Chapter V. Search After The Supposed Island Of Babeque - Desertion Of The Pinta.

Chapter Vi. Discovery Of Hispaniola.

Chapter Vii. Coasting Of Hispaniola.

Chapter Vii. Shipwreck.

Chapter Ix. Transactions With The Natives.

Chapter X. Building Of The Fortress Of La Navidad.

Chapter Xi. Regulation Of The Fortress Of La Navidad - Departure Of Columbus For Spain.

Book V.

Chapter I. Coasting Toward The Eastern End Of Hispaniola - Meeting With Pinzon - Affair With The Natives At The Gulf Of Samana.

Chapter Ii. Return Voyage - Violent Storms Arrival At The Azores.

Chapter Iii. Transactions At The Island Of St. Mary's.

Chapter Iv. Arrival At Portugal - Visit To The Court.

Chapter V. Reception Of Columbus At Palos.

Chapter Vi. Reception Of Columbus By The Spanish Court At Barcelona.

Chapter Vii. Sojourn Of Columbus At Barcelona Attentions Paid Him By The Sovereigns And Courtiers.

Chapter Viii. Papal Bull Of Partition - Preparations For A Second Voyage Of Columbus.

Chapter Ix. Diplomatic Negotiations Between The Courts Of Spain And Portugal With Respect To The New Discoveries.

Chapter X. Further Preparations For The Second Voyage - Character Of Alonso De Ojeda - Difference Of Columbus With Soria And Fonseca.

Book Vi.

Chapter I. Departure Of Columbus On His Second Voyage Discovery Of The Caribbean Islands.

Chapter Ii. Transactions At The Island Of Guadaloupe.

Chapter Iii. Cruise Among The Caribbean Islands.

Chapter Iv. Arrival At The Harbor Of La Navidad - Disaster Of The Fortress.

Chapter V. Transactions With The Natives Suspicious Conduct Of Guacanagari.

Chapter Vi. Founding Of The City Of Isabella - Maladies Of The Spaniards.

Chapter Vii. Expedition Of Alonso De Ojeda To Explore The Interior Of The Island - Dispatch Of The Ships To Spain.

Chapter Viii. Discontents At Isabella - Mutiny Of Bernal Diaz De Pisa.

Chapter Ix. Expedition Of Columbus To The Mountains Of Cibao.

[1494.]

Chapter X. Excursion Of Juan De Luxan Among The Mountains - Customs And Characteristics Of The Natives - Columbus Returns To Isabella.

Chapter Xi. Arrival Of Columbus At Isabella - Sickness Of The Colony.

Chapter Xii. Distribution Of The Spanish Forces In The Interior - Preparations For A Voyage To Cuba.

Book Vii.

Chapter I. Voyage To The East End Of Cuba.

Chapter Ii. Discovery Of Jamaica.

Chapter Iii. Return To Cuba - Navigation Among The Islands Called The Queen's Gardens.

Chapter Iv. Coasting Of The Southern Side Of Cuba.

Chapter V. Return Of Columbus Along The Southern Coast Of Cuba,

Chapter Vi. Coasting Voyage Along The South Side Of Jamaica.

Chapter Vii. Voyage Along The South Side Of Hispaniola, And Return To Isabella.

Book Viii.

Chapter I. Arrival Of The Admiral At Isabella - Character Of Bartholomew Columbus.

Chapter Ii. Misconduct Of Don Pedro Margarite, And His Departure From The Island.

Chapter Iii. Troubles With The Natives Alonzo De Ojeda Besieged By Caonabo.

Chapter Iv. Measures Of Columbus To Restore The Quiet Op The Island - Expedition Of Ojeda To Surprise Caonabo.

Chapter V. Arrival Of Antonio De Torres With Four Ships From Spain - His Return With Indian Slaves.

Chapter Vi. Expedition Of Columbus Against The Indians Of The Vega - Battle.

Chapter Vii. Subjugation Of The Natives - Imposition Of Tribute.

Chapter Viii. Intrigues Against Columbus In The Court Of Spain - Aguado Sent To Investigate The Affairs Of Hispaniola.

Chapter Ix. Arrival Of Aguado At Isabella - His Arrogant Conduct - Tempest In The Harbor.

Chapter X. Discovery Of The Mines Of Hayna.

Book Ix.

Chapter I. Return Of Columbus To Spain With Aguado.

Chapter Ii. Decline Of The Popularity Of Columbus In Spain - His Reception By The Sovereigns At Burgos - He Proposes A Third Voyage.

Chapter Iii. Preparations For A Third Voyage - Disappointments And Delays.

Book X.

Chapter I. Departure Of Columbus From Spain On His Third Voyage - Discovery Of Trinidad.

Chapter Ii. Voyage Through The Gulf Of Paria.

Chapter Iii. Continuation Of The Voyage Through The Gulf Of Paria - Return To Hispaniola.

Chapter Iv. Speculations Of Columbus Concerning The Coast Of Paria.

Book Xi.

Chapter I. Administration Of The Adelantado.—Expedition To The Province Of Xaragua.

Chapter Ii. Establishment Of A Chain Of Military Posts.—Insurrection Of Guarionex, The Cacique Of The Vega.

Chapter Iii. The Adelantado Repairs To Xaragua To Receive Tribute.

Chapter Iv. Conspiracy Of Roldan.

Chapter V. The Adelantado Repairs To The Vega In Relief Of Fort Conception.—His Interview With Roldan.

Chapter Vi. Second Insurrection Of Guarionex, And His Flight To The Mountains Of Ciguay.

Chapter Vii. Campaign Of The Adelantado In The Mountains Of Ciguay.

Book Xii.

Chapter I. Confusion In The Island.—Proceedings Of The Rebels At Xaragua.

Chapter Ii. Negotiation Of The Admiral With The Rebels.—Departure Of Ships For Spain.

Chapter Iii. Negotiations And Arrangements With The Rebels.

Chapter Iv. Grants Made To Roldan And His Followers.—Departure Of Several Of The Rebels For Spain.

Chapter V. Arrival Of Ojeda With A Squadron At The Western Part Of The Island.—Roldan Sent To Meet Him.

Chapter Vi. Manoevres Of Roldan And Ojeda.

Chapter Vii. Conspiracy Of Guevara And Moxica.

Book Xiii.

Chapter I. Representations At Court Against Columbus.—Bobadilla Empowered To Examine Into His Conduct.

Chapter Ii. Arrival Of Bobadilla At San Domingo—His Violent Assumption Of The Command.

Chapter Iii. Columbus Summoned To Appear Before Bobadilla.

Chapter Iv. Columbus And His Brothers Arrested And Sent To Spain In Chains.

Book Xiv.

Chapter I. Sensation In Spain On The Arrival Of Columbus In Irons.—His Appearance At Court.

Chapter Ii. Contemporary Voyages Of Discovery.

Chapter Iii. Nicholas De Ovando Appointed To Supersede Bobadilla.

Chapter Iv. Proposition Of Columbus Relative To The Recovery Of The Holy Sepulchre.

Chapter V. Preparations Of Columbus For A Fourth Voyage Of Discovery.

Book Xv.

Chapter I. Departure Of Columbus On His Fourth Voyage.—Refused Admission To The Harbor Of San Domingo.—Exposed To A Violent Tempest.

Chapter Ii. Voyage Along The Coast Of Honduras.

Chapter Iii. Voyage Along The Mosquito Coast, And Transactions At Cariari.

Chapter Iv. Voyage Along Costa Rica.—Speculations Concerning The Isthmus At Veragua.

Chapter V. Discovery Of Puerto Bello And El Retrete.—Columbus Abandons The Search After The Strait.

Chapter Vi. Return To Veragua.—The Adelantado Explores The Country.

Chapter Vii. Commencement Of A Settlement On The River Belen.—Conspiracy Of The

Natives.—Expedition Of The Adelantado To Surprise Quiban.

Chapter Viii. Disasters Of The Settlement.

Chapter Ix. Distress Of The Admiral On Board Of His Ship.—Ultimate Relief Of The Settlement.

Chapter X. Departure From The Coast Of Veragua.—Arrival At Jamaica.—Stranding Of The Ships.

Book Xvi.

Chapter I. Arrangement Of Diego Mendez With The Caciques For Supplies Of Provisions.—Sent To San Domingo By Columbus In Quest Of Relief.

Chapter Ii. Mutiny Of Porras.

Chapter Iii. Scarcity Of Provisions.—Strategem Of Columbus To Obtain Supplies From The Natives.

Chapter Iv. Mission Of Diego De Escobar To The Admiral.

Chapter V. Voyage Of Diego Mendez And Bartholomew Fiesco In A Canoe To Hispaniola.

Chapter Vi. Overtures Of Columbus To The Mutineers.—Battle Of The Adelantado With

Porras And His Followers.

Book Xvii.

Chapter I. Administration Of Ovando In Hispaniola.—Oppression Of The Natives.

Chapter Ii. Massacre At Xaragua.—Fate Of Anacaona.

Chapter Iii. War With The Natives Of Higuey.

Chapter Iv. Close Of The War With Higuey.—Fate Of Cotabanama.

Book Xviii.

Chapter I. Departure Of Columbus For San Domingo.—His Return To Spain.

Chapter Ii. Illness Of Columbus At Seville.—Application To The Crown For A Restitution Of His Honors.—Death Of Isabella.

Chapter Iii. Columbus Arrives At Court.—Fruitless Application To The King For Redress.

Chapter Iv. Death Of Columbus.

Chapter V. Observations On The Character Of Columbus.

Appendix:

No. I. Transportation Of The Remains Of Columbus From St. Domingo To The Havana.

No. Ii. Notice Of The Descendants Of Columbus.

No. Iii. Fernando Columbus.

No. Iv. Age Of Columbus.

No. V. Lineage Of Columbus.

No. Vi. Birthplace Of Columbus.

No. Vii. The Colombos.

No. Viii. Expedition Of John Of Anjou.

No. Ix. Capture Of The Venetian Galleys, By Colombo The Younger.

No. X. Amerigo Vespucci.

No. Xi. Martin Alonzo Pinzon.

No. Xii. Rumor Of The Pilot Said To Have Died In The House Of Columbus.

No. Xiii. Martin Behem.

No. Xiv. Voyages Of The Scandinavians.

No. Xv. Circumnavigation Of Africa By The Ancients.

No. Xvi. Of The Ships Of Columbus.

No. Xvii. Route Of Columbus In His First Voyage.

No. Xviii. Principles Upon Which The Sums Mentioned In This Work Have Been Reduced Into Modern Currency.

No. Xix. Prester John:

No. Xx. Marco Polo.

No. Xxi. The Work Of Marco Polo.

No. Xxii. Sir John Mandeville.

No. Xxiii. The Zones.

No. Xxiv. Of The Atlantis Of Plato.

No. Xxv. The Imaginary Island Of St. Brandan.

No. Xxvi. The Island Of The Seven Cities.

No. Xxvii. Discovery Of The Island Of Madeira.

No. Xxviii. Las Casas.

No. Xxix. Peter Martyr.

No. Xxx. Oviedo.

No. Xxxi. Cura De Los Palacios.

No. Xxxii. "Navigatione Del Re De Castiglia Delle Isole E Paese Nuovamente Ritrovate."

No. Xxxiii. Antonio De Herrera.

No. Xxxiv. Bishop Fonseca.

No. Xxxv. Of The Situation Of The Terrestrial Paradise.

No. Xxxvi. Will Of Columbus.

No. Xxxvii. Signature Of Columbus.

No. Xxxviii. A Visit To Palos.

The Life And Voyages Of Christopher Columbus, W. Irving

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Germany

Edited and revised by Juergen Beck.

ISBN: 9783849642020

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

www.facebook.com/jazzybeeverlag

" Venient annis,

Saecula seris, quibus Oceanus

Vincula rerum laxet, et ingens

Pateat tellus, Tethysque novos

Detegat Orbes nee sit terris

Ultima Thule."

SENECA, MEDEA.

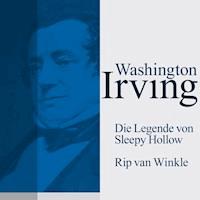

Washington Irving – A Biographical Primer

Washington Irving (1783-1859), American man of letters, was born at New York on the 3rd of April 1783. Both his parents were immigrants from Great Britain, his father, originally an officer in the merchant service, but at the time of Irving's birth a considerable merchant, having come from the Orkneys, and his mother from Falmouth. Irving was intended for the legal profession, but his studies were interrupted by an illness necessitating a voyage to Europe, in the course of which he proceeded as far as Rome, and made the acquaintance of Washington Allston. He was called to the bar upon his return, but made little effort to practice, preferring to amuse himself with literary ventures. The first of these of any importance, a satirical miscellany entitled Salmagundi, or the Whim-Whams andOpinions of Launcelot Langstaff and others, written in conjunction with his brother William and J. K. Paulding, gave ample proof of his talents as a humorist. These were still more conspicuously displayed in his next attempt, A History of New York from theBeginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by “Diedrich Knickerbocker” (2 vols., New York, 1809). The satire of Salmagundi had been principally local, and the original design of “Knickerbocker's” History was only to burlesque a pretentious disquisition on the history of the city in a guidebook by Dr Samuel Mitchell. The idea expanded as Irving proceeded, and he ended by not merely satirizing the pedantry of local antiquaries, but by creating a distinct literary type out of the solid Dutch burgher whose phlegm had long been an object of ridicule to the mercurial Americans. Though far from the most finished of Irving's productions, “Knickerbocker” manifests the most original power, and is the most genuinely national in its quaintness and drollery. The very tardiness and prolixity of the story are skillfully made to heighten the humorous effect.

Upon the death of his father, Irving had become a sleeping partner in his brother's commercial house, a branch of which was established at Liverpool. This, combined with the restoration of peace, induced him to visit England in 1815, when he found the stability of the firm seriously compromised. After some years of ineffectual struggle it became bankrupt. This misfortune compelled Irving to resume his pen as a means of subsistence. His reputation had preceded him to England, and the curiosity naturally excited by the then unwonted apparition of a successful American author procured him admission into the highest literary circles, where his popularity was ensured by his amiable temper and polished manners. As an American, moreover, he stood aloof from the political and literary disputes which then divided England. Campbell, Jeffrey, Moore, Scott, were counted among his friends, and the last-named zealously recommended him to the publisher Murray, who, after at first refusing, consented (1820) to bring out The Sketch Book ofGeoffrey Crayon, Gent. (7 pts., New York, 1819-1820). The most interesting part of this work is the description of an English Christmas, which displays a delicate humor not unworthy of the writer's evident model Addison. Some stories and sketches on American themes contribute to give it variety; of these Rip van Winkle is the most remarkable. It speedily obtained the greatest success on both sides of the Atlantic. Bracebridge Hall, or the Humourists (2 vols., New York), a work purely English in subject, followed in 1822, and showed to what account the American observer had turned his experience of English country life. The humor is, nevertheless, much more English than American. Tales of a Traveller (4 pts.) appeared in 1824 at Philadelphia, and Irving, now in comfortable circumstances, determined to enlarge his sphere of observation by a journey on the continent. After a long course of travel he settled down at Madrid in the house of the American consul Rich. His intention at the time was to translate the Coleccionde los Viajes y Descubrimientos (Madrid, 1825-1837) of Martin Fernandez de Navarrete; finding, however, that this was rather a collection of valuable materials than a systematic biography, he determined to compose a biography of his own by its assistance, supplemented by independent researches in the Spanish archives. His History of the Life and Voyages ofChristopher Columbus (London, 4 vols.) appeared in 1828, and obtained a merited success. The Voyages and Discoveries ofthe Companions of Columbus (Philadelphia, 1831) followed; and a prolonged residence in the south of Spain gave Irving materials for two highly picturesque books, A Chronicle of theConquest of Granada from the MSS. of [an imaginary] FrayAntonio Agapida (2 vols., Philadelphia, 1829), and The Alhambra:a series of tales and sketches of the Moors and Spaniards (2 vols., Philadelphia, 1832). Previous to their appearance he had been appointed secretary to the embassy at London, an office as purely complimentary to his literary ability as the legal degree which he about the same time received from the university of Oxford.

Returning to the United States in 1832, after seventeen years' absence, he found his name a household word, and himself universally honored as the first American who had won for his country recognition on equal terms in the literary republic. After the rush of fêtes and public compliments had subsided, he undertook a tour in the western prairies, and returning to the neighborhood of New York built for himself a delightful retreat on the Hudson, to which he gave the name of “Sunnyside.” His acquaintance with the New York millionaire John Jacob Astor prompted his next important work — Astoria (2 vols., Philadelphia, 1836), a history of the fur-trading settlement founded by Astor in Oregon, deduced with singular literary ability from dry commercial records, and, without labored attempts at word-painting, evincing a remarkable faculty for bringing scenes and incidents vividly before the eye. TheAdventures of Captain Bonneville (London and Philadelphia, 1837), based upon the unpublished memoirs of a veteran explorer, was another work of the same class. In 1842 Irving was appointed ambassador to Spain. He spent four years in the country, without this time turning his residence to literary account; and it was not until two years after his return that Forster's life of Goldsmith, by reminding him of a slight essay of his own which he now thought too imperfect by comparison to be included among his collected writings, stimulated him to the production of his Life of Oliver Goldsmith, with Selections fromhis Writings (2 vols., New York, 1849). Without pretensions to original research, the book displays an admirable talent for employing existing material to the best effect. The same may be said of The Lives of Mahomet and his Successors (New York, 2 vols., 1840-1850). Here as elsewhere Irving correctly discriminated the biographer's province from the historian's, and leaving the philosophical investigation of cause and effect to writers of Gibbon's caliber, applied himself to represent the picturesque features of the age as embodied in the actions and utterances of its most characteristic representatives. His last days were devoted to his Life of George Washington (5 vols., 1855-1859, New York and London), undertaken in an enthusiastic spirit, but which the author found exhausting and his readers tame. His genius required a more poetical theme, and indeed the biographer of Washington must be at least a potential soldier and statesman. Irving just lived to complete this work, dying of heart disease at Sunnyside, on the 28th of November 1859.

Although one of the chief ornaments of American literature, Irving is not characteristically American. But he is one of the few authors of his period who really manifest traces of a vein of national peculiarity which might under other circumstances have been productive. “Knickerbocker's” History of NewYork, although the air of mock solemnity which constitutes the staple of its humor is peculiar to no literature, manifests nevertheless a power of reproducing a distinct national type. Had circumstances taken Irving to the West, and placed him amid a society teeming with quaint and genial eccentricity, he might possibly have been the first Western humorist, and his humor might have gained in depth and richness. In England, on the other hand, everything encouraged his natural fastidiousness; he became a refined writer, but by no means a robust one. His biographies bear the stamp of genuine artistic intelligence, equally remote from compilation and disquisition. In execution they are almost faultless; the narrative is easy, the style pellucid, and the writer's judgment nearly always in accordance with the general verdict of history. Without ostentation or affectation, he was exquisite in all things, a mirror of loyalty, courtesy and good taste in all his literary connexions, and exemplary in all the relations of domestic life. He never married, remaining true to the memory of an early attachment blighted by death.

The principal edition of Irving' s works is the “Geoffrey Crayon,” published at New York in 1880 in 26 vols. His Life and Letters was published by his nephew Pierre M. Irving (London, 1862-1864, 4 vols.; German abridgment by Adolf Laun, Berlin, 1870, 2 vols.) There is a good deal of miscellaneous information in a compilation entitled Irvingiana (New York, 1860); and W. C. Bryant's memorial oration, though somewhat too uniformly laudatory, may be consulted with advantage. It was republished in Studies of Irvine (1880) along with C. Dudley Warner's introduction to the “Geoffrey Crayon” edition, and Mr. G. P. Putnam's personal reminiscences of Irving, which originally appeared in the Atlantic Monthly. See also Washington Irving (1881), by C. D. Warner, in the “American Men of Letters” series; H. R. Haweis, American Humourists (London, 1883).

The Life And Voyages OfChristopher Columbus

PREFACE.

BEING at Bordeaux in the winter of 1825-6, I received a letter from Mr. Alexander Everett, Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States at Madrid, informing me of a work then in the press, edited by Don Martin Fernandez de Navarrete, Secretary of the Royal Academy of History, etc. etc. , containing a collection. of documents relative to the voyages of Columbus, among which were many of a highly important nature, recently discovered. Mr. Everett, at the same time, expressed an opinion that a version of the work into English, by one of our own country, would be peculiarly desirable. I concurred with him in the opinion; and, having for some time intended a visit to Madrid, I shortly afterward set off for that capital, with an idea of undertaking, while there, the translation of the work.

Soon after my arrival, the publication of M. Navarrete made its appearance. I found it to contain many documents, hitherto unknown, which threw additional lights on the discovery of the New World, and which reflected the greatest credit on the industry and activity of the learned editor. Still the whole presented rather a mass of rich materials for history, than a history itself. And invaluable as such stores may be to the laborious inquirer, the sight of disconnected papers and official documents is apt to be repulsive to the general reader who seeks for clear and continued narrative. These circumstances made me hesitate in my proposed undertaking; yet the subject was of so interesting and national a kind, that I could not willingly abandon it.

On considering the matter more maturely, I perceived that, although there were many books, in various languages, relative to Columbus, they all contained limited and incomplete accounts of his life and voyages; while numerous valuable tracts on the subject existed only in manuscript or in the form of letters, journals, and public muniments. It appeared to me that a history, faithfully digested from these various materials, was a desideratum in literature, and would be a more satisfactory occupation to myself, and a more acceptable work to my country, than the translation I had contemplated.

I was encouraged to undertake such a work, by the great facilities which I found within my reach at Madrid. I was resident under the roof of the American Consul, O. Rich, Esq., one of the most indefatigable bibliographers in Europe, who, for several years, had made particular researches after every document relative to the early history of America. In his extensive and curious library, I found one of the best collections extant of Spanish colonial history, containing many documents for which I might search elsewhere in vain. This he put at my absolute command, with a frankness and unreserve seldom to be met with among the possessors of such rare and valuable works; and his library has been my main resource throughout the whole of my labors.

I found also the Royal Library of Madrid, and the library of the Jesuits' College of San Isidro, two noble and extensive collections, open to access, and conducted with great order and liberality. From Don Martin Fernandez de Navarrete, who communicated various valuable and curious pieces of information, discovered in the course of his researches, I received the most obliging assistance; nor can I refrain from testifying my admiration of the self-sustained zeal of that estimable man, one of the last veterans of Spanish literature, who is almost alone, yet indefatigable in his labors, in a country where, at present, literary exertion meets with but little excitement or reward.

I must acknowledge, also, the liberality of the Duke of Veragua, the descendant and representative of Columbus, who submitted the archives of his family to my inspection, and took a personal interest in exhibiting the treasures they contained. Nor, lastly, must I omit my deep obligations to my excellent friend Don Antonio de Uguina, treasurer of the Prince Francisco, a gentleman of talents and erudition, and particularly versed in the history of his country and its dependencies. To his unwearied investigations, and silent and unavowed contributions, the world is indebted for much of the accurate information, recently imparted, on points of early colonial history. In the possession of this gentleman are most of the papers of his deceased friend, the late historian Munos, who was cut off in the midst of his valuable labors. These, and various other documents, have been imparted to me by Don Antonia, with a kindness and urbanity which greatly increased, yet lightened, the obligation.

With these, and other aids incidentally afforded me by my local situation, I have endeavored, to the best of my abilities, and making the most of the time which I could allow myself during a sojourn in a foreign country, to construct this history. I have diligently collated all the works that I could find relative to my subject, in print and manuscript; comparing them, as far as in my power, with original documents, those sure lights of historic research; endeavoring to ascertain the truth amid those contradictions which will inevitably occur, where several persons have recorded the same facts, viewing them from different points, and under the influence of different interests and feelings.

In the execution of this work I have avoided indulging in mere speculations or general reflections, excepting such as rose naturally out of the subject, preferring to give a minute and circumstantial narrative, omitting no particular that appeared characteristic of the persons, the events, or the times; and endeavoring to place every fact in such a point of view, that the reader might perceive its merits, and draw his own maxims and conclusions.

As many points of the history required explanations, drawn from contemporary events and the literature of the times, I have preferred, instead of incumbering the narrative, to give detached illustrations at the end of the work. This also enabled me to indulge in greater latitude of detail, where the subject was of a curious or interesting nature, and the sources of information such as not to be within the common course of reading.

After all, the work is presented to the public with extreme diffidence. All that I can safely claim is, an earnest desire to state the truth, an absence from prejudices respecting the nations mentioned in my history, a strong interest in my subject, and a zeal to make up by assiduity for many deficiencies of which I am conscious.

WASHINGTON IRVING.

Madrid, 1827.

P. S. I have been surprised at finding myself accused by some American writer of not giving sufficient credit to Don Martin Fernandez de Navarrete for the aid I had derived from his collection of documents. I had thought I had sufficiently shown, in the preceding preface, which appeared with my first edition, that his collection first prompted my work and subsequently furnished its principal materials; and that I had illustrated this by citations at the foot of almost every page. In preparing this revised edition, I have carefully and conscientiously examined into the matter, but find nothing to add to the acknowledgments already made.

To show the feelings and opinions of M. Navarrete himself with respect to my work and myself, I subjoin an extract from a letter received from that excellent man, and a passage from the introduction to the third volume of his collection. Nothing but the desire to vindicate myself on this head would induce me to publish extracts so laudatory.

From a letter dated Madrid, April 1st, 1831.

I congratulate myself that the documents and notices which I published in my collection about the first occurrences in the history of America, have fallen into hands so able to appreciate their authenticity, to examine them critically, and to circulate them in all directions; establishing fundamental truths which hitherto have been adulterated by partial or systematic writers.

In the introduction to the third volume of his Collection of Spanish Voyages, Mr. Navarrete cites various testimonials he has received since the publication of his two first volumes of the utility of his work to the republic of letters.

"A signal proof of this," he continues, "is just given us by Mr. Washington Irving in the History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, which he has published with a success as general as it is well merited. We said in our introduction that we did not propose to write the history of the admiral, but to publish notes and materials that it might be written with veracity; and it is fortunate that the first person to profit by them should be a literary man, judicious and erudite, already known in his own country and in Europe by other works of merit. Resident in Madrid, exempt from the rivalries which have influenced some European natives with respect to Columbus and his discoveries; having an opportunity to examine excellent books and precious manuscripts; to converse with persons instructed in these matters, and having always at hand the authentic documents which we had just published, he has been enabled to give to his history that fullness, impartiality, and exactness, which make it much superior to those of the writers who preceded him. To this he adds his regular method, and convenient distribution; his style animated, pure, and elegant; the notice of various personages who mingled in the concerns of Columbus; and the examination of various questions, in which always shine sound criticism, erudition, and good taste."

BOOK I.

WHETHER in old times, beyond the reach of history or tradition, and in some remote period of civilization, when, as some imagine, the arts may have flourished to a degree unknown to those whom we term the Ancients, there existed an intercourse between the opposite shores of the Atlantic; whether the Egyptian legend, narrated by Plato, respecting the island of Atlantis was indeed no fable, but the obscure tradition of some vast country, engulfed by one of those mighty convulsions of our globe, which have left traces of the ocean on the summits of lofty mountains, must ever remain matters of vague and visionary speculation. As far as authenticated history extends, nothing was known of terra firma, and the islands of the western hemisphere, until their discovery toward the close of the fifteenth century. A wandering bark may occasionally have lost sight of the landmarks of the old continents, and been driven by tempests across the wilderness of waters long before the invention of the compass, but never returned to reveal the secrets of the ocean. And though, from time to time, some document has floated to the shores of the old world, giving to its wondering inhabitants evidences of land far beyond their watery horizon; yet no one ventured to spread a sail, and seek that land enveloped in mystery and peril. Or if the legends of the Scandinavian voyagers be correct, and their mysterious Vinland was the coast of Labrador, or the shore of Newfoundland, they had but transient glimpses of the new world, leading to no certain or permanent knowledge, and in a little time lost again to mankind. Certain it is that at the beginning of the fifteenth century, when the most intelligent minds were seeking in every direction for the scattered lights of geographical knowledge, a profound ignorance prevailed among the learned as to the western regions of the Atlantic; its vast waters were regarded with awe and wonder, seeming to bound the world as with a chaos, into which conjecture could not penetrate, and enterprise feared to adventure. We need no greater proofs of this than the description given of the Atlantic by Xerif al Edrisi, surnamed the Nubian, an eminent Arabian writer, whose countrymen were the boldest navigators of the middle ages, and possessed all that was then known of geography.

"The ocean," he observes, " encircles the ultimate bounds of the inhabited earth, and all beyond it is unknown. No one has been able to verify anything concerning it, on account of its difficult and perilous navigation, its great obscurity, its profound depth, and frequent tempests; through fear of its mighty fishes, and its haughty winds; yet there are many islands in it, some peopled, others uninhabited. There is no mariner who dares to enter into its deep waters; or if any have done so, they have merely kept along its coasts, fearful of departing from them. The waves of this ocean, although they roll as high as mountains, yet maintain themselves without breaking; for if they broke, it would be impossible for ship to plough them."

It is the object of the following work, to relate the deeds and fortunes of the mariner who first had the judgment to divine, and the intrepidity to brave the mysteries of this perilous deep; and who, by his hardy genius, his inflexible constancy, and his heroic courage, brought the ends of the earth into communication with each other. The narrative of his troubled life is the link which connects the history of the old world with that of the new.

CHAPTER I. BIRTH, PARENTAGE, AND EARLY LIFE OF COLUMBUS.

CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS, or Colombo, as the name is written in Italian (see Note), was born in the city of Genoa, about the year 1435. He was the son of Dominico Colombo, a wool-comber, and Susannah Fonatanarossa, his wife, and it would seem that his ancestors had followed the same handicraft for several generations in Genoa. Attempts have been made to prove him of illustrious descent, and several noble houses have laid claim to him since his name has become so renowned as to confer rather than receive distinction. It is possible some of them may be in the right, for the feuds in Italy in those ages had broken down and scattered many of the noblest families, and while some branches remained in the lordly heritage of castles and domains, others were confounded with the humblest population of the cities. The fact, however, is not material to his fame; and it is a higher proof of merit to be the object of contention among various noble families, than to be able to substantiate the most illustrious lineage. His son Fernando had a true feeling on the subject. " I am of opinion, " says he, " that I should derive less dignity from any nobility of ancestry, than from being the son of such a father."

Note: Columbus Latinized his name in his letters according to the usage of the time, when Latin was the language of learned correspondence. In subsequent life when in Spain he recurred to what was supposed to be the original Roman name of the family, Cokwrus, which he abbreviated to Colon, to adapt it to the Castilian tongue. Hence he is known in Spanish history as Christoval Colon. In the present work the name will be written Columbus, being the one by which he is most known throughout the world.

Columbus was the oldest of four children; having two brothers, Bartholomew and Giacomo, or James (written Diego in Spanish), and one sister, of whom nothing is known but that she was married to a person in obscure life called Giacomo Bavarello. At a very early age Columbus evinced a decided inclination for the sea; his education, therefore, was mainly directed to fit him for maritime life, but was as general as the narrow means of his father would permit. Besides the ordinary branches of reading, writing, grammar, and arithmetic, he was instructed in the Latin tongue, and made some proficiency in drawing and design. For a short time, also, he was sent to the university of Pavia, where he studied geometry, geography, astronomy, and navigation. He then returned to Genoa, where, according to a contemporary historian, he assisted his father in his trade of wool-combing. This assertion is indignantly contradicted by his son Fernando, though there is nothing in it improbable, and he gives us no information of his father's occupation to supply its place. He could not, however, have remained long in this employment, as, according to his own account, he entered upon a nautical life when but fourteen years of age.

In tracing the early history of a man like Columbus, whose actions have had a vast effect on human affairs, it is interesting to notice how much has been owing to external influences, how much to an inborn propensity of the genius. In the latter part of his life, when, impressed with the sublime events brought about through his agency, Columbus looked back upon his career with a solemn and superstitious feeling, he attributed his early and irresistible inclination for the sea, and his passion for geographical studies, to an impulse from the Deity preparing him for the high decrees he was chosen to accomplish.

The nautical propensity, however, evinced by Columbus in early life, is common to boys of enterprising spirit and lively imagination brought up in maritime cities; to whom the sea is the highroad to adventure and the region of romance. Genoa, too, walled in and straitened on the land side by rugged mountains, yielded but little scope for enterprise on shore, while an opulent and widely extended commerce, visiting every country, and a roving marine, battling in every sea, naturally led forth her children upon the waves, as their propitious element. Many, too, were induced to emigrate by the violent factions which raged within the bosom of the city, and often dyed its streets with blood. A historian of Genoa laments this proneness of its youth to wander. They go, said he, with the intention of returning when they shall have acquired the means of living comfortably and honorably in their native place; but we know from long experience, that of twenty who thus depart scarce two return: either dying abroad, or taking to themselves foreign wives, or being loath to expose themselves to the tempests of civil discords which distract the republic.

The strong passion for geographical knowledge, also, felt by Columbus in early life, and which inspired his after career, was incident to the age in which he lived. Geographical discovery was the brilliant path of light which was forever to distinguish the fifteenth century. During a long night of monkish bigotry and false learning, geography, with the other sciences, had been lost to the European nations. Fortunately it had not been lost to mankind: it had taken refuge in the bosom of Africa. While the pedantic schoolmen of the cloisters were wasting time and talent, and confounding erudition by idle reveries and sophistical dialectics, the Arabian sages, assembled at Senaar, were taking the measurement of a degree of latitude, and calculating the circumference of the earth, on the vast plains of Mesopotamia.

True knowledge, thus happily preserved, was now making its way back to Europe. The revival of science accompanied the revival of letters. Among the various authors which the awakening zeal for ancient literature had once more brought into notice, were Pliny, Pomponius Mela, and Strabo. From these was regained a fund of geographical knowledge, which had long faded from the public mind. Curiosity was aroused to pursue this forgotten path, thus suddenly reopened. A translation of the work of Ptolemy had been made into Latin, at the commencement of the century, by Emanuel Chrysoleras, a noble and learned Greek, and had thus been rendered more familiar to the Italian students. Another translation had followed, by James Angel de Scarpiaria, of which fair and beautiful copies became common in the Italian libraries. The writings also began to be sought after of Avarroes, Alfraganus, and other Arabian sages, who had kept the sacred fire of science alive, during the interval of European darkness.

The knowledge thus reviving was limited and imperfect; yet, like the return of morning light, it seemed to call a new creation into existence, and broke, with all the charm of wonder, upon imaginative minds. They were surprised at their own ignorance of the world around them. Every step was discovery, for every region beyond their native country was in a manner terra incognita.

Such was the state of information and feeling with respect to this interesting science, in the early part of the fifteenth century. An interest still more intense was awakened by the discoveries which began to be made along the Atlantic coasts of Africa; and must have been particularly felt among a maritime and commercial people like the Genoese. To these circumstances may we ascribe the enthusiastic devotion which Columbus imbibed in his childhood for cosmographical studies, and which influenced all his after fortunes.

The short time passed by him at the university of Pavia was barely sufficient to give him the rudiments of the necessary sciences; the familiar acquaintance with them, which he evinced in after life, must have been the result of diligent self -schooling, in casual hours of study amid the cares and vicissitudes of a rugged and wandering life. He was one of those men of strong natural genius, who, from having to contend at their very outset with privations and impediments! acquire an intrepidity in encountering and a facility in vanquishing difficulties, throughout their career. Such men learn to effect great purposes with small means, supplying this deficiency by the resources of their own energy and invention. This, from his earliest commencement, throughout the whole of his life, was one of the remark able features, in the history of Columbus. In every undertaking, the scantiness and apparent insufficiency of his means enhance the grandeur or his achievements.

CHAPTER II. EARLY VOYAGES OF COLUMBUS.

COLUMBUS, as has-been observed, commenced his nautical career when about fourteen years of age. His first voyages were made with a distant relative named Colombo, a hardy veteran of the seas, who had risen to some distinction by his bravery, and is occasionally mentioned in old chronicles; sometimes as commanding a squadron of his own, sometimes as an admiral in the Genoese service. He appears to have been bold and adventurous; ready to fight in any cause, and to seek quarrel wherever it might lawfully be found.

The seafaring life of the Mediterranean In those days was hazardous and daring. A commercial expedition resembled a warlike cruise, and the maritime merchant had often to fight his way from port to port. Piracy was almost legalized. The frequent feuds between the Italian states; the cruisings of the Catalonians; the armadas fitted out by private noblemen, who exercised a kind of sovereignty in their own domains, and kept petty armies and navies in their pay; the roving ships and squadrons of private adventurers, a kind of naval Condottieri, sometimes employed by the hostile governments, sometimes scouring the seas in search of lawless booty; these, with the holy wars waged against the Mahometan powers, rendered the narrow seas, to which navigation was principally confined, scenes of hardy encounters and trying reverses.

Such was the rugged school in which Columbus was reared, and it would have been deeply interesting to have marked the early development of his genius amid its stern adversities. All this instructive era of his history, however, is covered with darkness. His son Fernando, who could have best elucidated it, has left it in obscurity, or has now and then perplexed us with cross lights; perhaps unwilling, from a principle of mistaken pride, to reveal the indigence and obscurity from which his father so gloriously emerged.

The first voyage in which we have any account of his being engaged was a naval expedition, fitted out in Genoa in 1459 by John of Anjoil, Duke of Calabria, to make a descent upon Naples, in the hope of recovering that kingdom for his father King Reinier, or Renato, otherwise called Rene, Count of Provence. The republic of Genoa aided him with ships and money. The brilliant nature of the enterprise attracted the attention of daring and restless spirits. The chivalrous nobleman, the soldier of fortune, the hardy corsair, the desperate adventurer, the mercenary partisan, all hastened to enlist under the banner of Anjou. The veteran Colombo took a part in this expedition, either with galleys of his own, or as a commander of the Genoese squadron, and with him embarked his youthful relative, the future discoverer.

The struggle of John of Anjou for the crown of Naples lasted about four years, with varied fortune, but was finally unsuccessful. The naval part of the expedition, in which Columbus was engaged, signalized itself by acts of intrepidity; and at one time when the duke was reduced to take refuge in the island of Ischia, a handful of galleys scoured and controlled the bay of Naples.

In the course of this, gallant but ill-fated enterprise, Columbus was detached on a perilous cruise, to cut out a galley from the harbor of Tunis. This is incidentally mentioned by himself in a letter written many years afterward. It happened to me, he says, that King Reinier (whom God has taken to himself) sent me to Tunis, to capture the galley Fernandina, and when I arrived off the island of St. Pedro, in Sardinia, I was informed that there were two ships and a carrack with the galley; by which intelligence my crew were so troubled that they determined to proceed no further, but to return to Marseilles for another vessel and more people; as I could not by any means compel them, I assented apparently to their wishes, altering the point of the compass and spreading all sail. It was then evening, and next morning we were within the Cape of Cartagena, while all were firmly of opinion that they were sailing toward Marseilles.

We have no further record of this bold cruise into the harbor of Tunis; but in the foregoing particulars we behold early indications of that resolute and persevering spirit which insured him success in his more important undertakings. His expedient to beguile a discontented crew into a continuation of the enterprise, by deceiving them with respect to the ship's course, will be found in unison with a stratagem of altering the reckoning, to which he had recourse in his first voyage of discovery.

During an interval of many years we have but one or two shadowy traces of Columbus. He is supposed to have been principally engaged on the Mediterranean and up the Levant; sometimes in commercial voyages; sometimes in the warlike contests between the Italian states; sometimes in pious and predatory expeditions against the Infidels. Historians have made him in 1474 captain of several Genoese ships, in the service of Louis XI. of France, and endangering the peace between that country and Spain by running down and capturing Spanish vessels at sea, on his own responsibility, as a reprisal for an irruption of the Spaniards into Roussillon. Again, in 1475, he is represented as brushing with his Genoese squadron in ruffling bravado by a Venetian fleet stationed off the island of Cyprus, shouting "Viva San Georgio!" the old war-cry of Genoa, thus endeavoring to pique the jealous pride of the Venetians and provoke a combat, though the rival republics were at peace at the time.

These transactions, however, have been erroneously attributed to Columbus. They were the deeds, or misdeeds, either of his relative the old Genoese admiral, or of a nephew of tie same, of kindred spirit, called Colombo the Younger, to distinguish him from his uncle. They both appear to have been fond of rough encounters, and not very scrupulous as to the mode of bringing them about. Fernando Columbus describes this Colombo the Younger as a famous corsair, so terrible for his deeds against the Infidels, that the Moorish mothers used to frighten their unruly children with his name. Columbus sailed with him occasionally, as he had done with his uncle, and, according to Fernando's account, commanded a vessel in his squadron on an eventful occasion.

Colombo the Younger, having heard that four Venetian galleys richly laden were on their return voyage from Flanders, lay in wait for them on the Portuguese coast, between Lisbon and Cape St. Vincent. A desperate engagement took place; the vessels grappled each other, and the crews fought hand to hand, and from ship to ship. The battle lasted from morning until evening, with great carnage on both sides. The vessel commanded by Columbus was engaged with a huge Venetian galley. They threw hand-grenades and other fiery missiles, and the galley was wrapped in flames. The vessels were fastened together by chains and grappling irons, and could not be separated; both were involved in one conflagration, and soon became a mere blazing mass. The crews threw themselves into the sea; Columbus seized an oar, which was floating within reach, and being an expert swimmer, attained the shore, though full two leagues distant. It pleased God, says his son Fernando, to give him strength, that he might preserve him for greater things. After recovering from his exhaustion he repaired to Lisbon, where he found many of his Genoese countrymen, and was induced to take up his residence.

Such is the account given by Fernando of his father's first arrival in Portugal; and it has been currently adopted by modern historians; but on examining various histories of the times, the battle here described appears to have happened several years after the date of the arrival of Columbus in that country. That he was engaged in the contest is not improbable; but he had previously resided for some time in Portugal. In fact, on referring to the history of that kingdom, we shall find, in the great maritime enterprises in which it was at that time engaged, ample attractions for a person of his inclinations and pursuits; and we shall be led to conclude, that his first visit to Lisbon was not the fortuitous result of a desperate adventure, but was undertaken in a spirit of liberal curiosity, and in the pursuit of honorable fortune.

CHAPTER III. PROGRESS OF DISCOVERY UNDER PRINCE HENRY OF PORTUGAL.

THE career of modern discovery had commenced shortly before the time of Columbus, and at the period of which we are treating was prosecuted with great activity by Portugal. Some have attributed its origin to a romantic incident in the fourteenth century. An Englishman of the name of Macham, flying to France with a lady of whom he was enamored, was driven far out of sight of land by stress of weather, and after wandering about the high seas, arrived at an unknown and uninhabited island, covered with beautiful forests, which was afterward called Madeira. Others have treated this account as a fable, and have pronounced the Canaries to be the first fruits of modern discovery. This famous group, the Fortunate Islands of the ancients, in which they placed their garden of the Hesperides, and whence Ptolemy commenced to count the longitude, had been long lost to the world. There are vague accounts, it is true, of their having received casual visits, at wide intervals, during the obscure ages, from the wandering bark of some Arabian, Norman, or Genoese adventurer; but all this was involved in uncertainty, and led to no beneficial result. It was not until the fourteenth century that they were effectually rediscovered, and restored to mankind. From that time they were occasionally visited by the hardy navigators of various countries. The greatest benefit produced by their discovery was, that the frequent expeditions made to them emboldened mariners to venture far upon the Atlantic, and familiarized them, in some degree, to its dangers.

The grand impulse to discovery was not given by chance, but was the deeply meditated effort of one master mind. This was Prince Henry of Portugal, son of John the First, surnamed the Avenger, and Philippa, of Lancaster, sister of Henry the Fourth of England. The character of this illustrious man, from whose enterprises the genius of Columbus took excitement, deserves particular mention.

Having accompanied his father into Africa, in an expedition against the Moors at Ceuta he received much information concerning the coast of Guinea, and other regions in the interior, hitherto unknown to Europeans, and conceived an idea that important discoveries were to be made by navigating along the western coast of Africa. On returning to Portugal, this idea became his ruling thought. Withdrawing from the tumult of a court to a country retreat in the Algarves, near Sagres, in the neighborhood of Cape St. Vincent, and in full view of the ocean, he drew around him men eminent in science, and prosecuted the study of those branches of knowledge connected with the maritime arts. He was an able mathematician, and made himself master of all the astronomy known to the Arabians of Spain.

On studying the works of the ancients, he found what he considered abundant proofs that Africa was circumnavigable. Eudoxus of Cyzicus was said to have sailed from the Red Sea into the ocean, and to have continued on to Gibraltar; and Hanno, the Carthaginian, sailing from Gibraltar with a fleet of sixty ships, and following the African coast, was said to have reached the shores of Arabia It is true these voyages had been discredited by several ancient writers, and the possibility of circumnavigating Africa, after being for a long time admitted by geographers, was denied by Hipparchus, who considered each sea shut up and land-bound in its peculiar basin; and that Africa was a continent continuing onward to the south pole, and surrounding the Indian Sea, so as to join Asia beyond the Ganges. This opinion had been adopted by Ptolemy, whose works, in the time of Prince Henry, were the highest authority in geography. The prince, however, clung to the ancient belief, that Africa was circumnavigable, and found his opinion sanctioned by various learned men of more modern date. To settle this question, and achieve the circumnavigation of Africa, was an object worthy the ambition of a prince, and his mind was fired with the idea of the vast benefits that would arise to his country should it be accomplished by Portuguese enterprise.

The Italians, or Lombards as they were called in the north of Europe, had long monopolized the trade of Asia. They had formed commercial establishments at Constantinople and in the Black Sea, -where they received the rich produce of the Spice Islands, lying near the equator; and the silks, the gums, the perfumes, the precious stones, and other luxurious commodities of Egypt and southern Asia, and distributed them over the whole of Europe. The republics of Venice and Genoa rose to opulence and power in consequence of this trade. They had factories in the most remote parts, even in the frozen regions of Moscovy and Norway. Their merchants emulated the magnificence of princes. All Europe was tributary to their commerce. Yet this trade had to pass through various intermediate hands, subject to the delays and charges of internal navigation, and the tedious and uncertain journeys of the caravan. For a long time the merchandise of India was conveyed by the Gulf of Persia, the Euphrates, the Indus, and the Oxus, to the Caspian and the Mediterranean seas; thence to take a new destination for the various marts of Europe. After the Soldan of Egypt had conquered the Arabs, and restored trade to its ancient channel, it was still attended with great cost and delay. Its precious commodities had to be conveyed by the Red Sea; thence on the backs of camels to the banks of the Nile, "whence they were transported to Egypt to meet the Italian merchants. Thus, while the opulent traffic of the East was engrossed by these adventurous monopolists, the price of every article was enhanced by the great expense of transportation.

It was the grand idea of Prince Henry, by circumnavigating Africa to open a direct and easy route to the source of this commerce, to turn it in a golden tide upon his country. He was. however, before the age in thought, and had to counteract ignorance and prejudice, and to endure the delays to which vivid and penetrating minds are subjected, from the tardy co-operations of the dull and the doubtful. The navigation of the Atlantic was yet in its infancy. Mariners looked with distrust upon a boisterous expanse, which appeared to have no opposite shore, and feared to venture out of sight of the landmarks.

Every bold headland and far-stretching promontory was a wall to bar their progress. They crept timorously along the Barbary shores, and thought they had accomplished a wonderful expedition when they had ventured a few degrees beyond the Straits of Gibraltar. Cape Non was long the limit of their daring; they hesitated to double its rocky point, beaten by winds and waves, and threatening to thrust them forth upon the raging deep.

Independent of these vague fears, they had others, sanctioned by philosophy itself. They still thought that the earth, at the equator, was girdled by a torrid zone, over which the sun held his vertical and fiery course, separating the hemispheres by a region of impassive heat. They fancied Cape Bojador the utmost boundary of secure enterprise, and had a superstitious belief that whoever doubled it would never return. They looked with dismay upon the rapid currents of its neighborhood, and the furious surf which beats upon its arid coast. They imagined that beyond it lay the frightful region of the torrid zone, scorched by a blazing sun; a region of fire, where the very waves, which beat upon the shores, boiled under the intolerable fervor of the heavens.

To dispel these errors, and to give a scope to navigation equal to the grandeur of his designs, Prince Henry established a naval college, and erected an observatory at Sagres, and he invited thither the most eminent professors of the nautical faculties; appointing as president James of Mallorca, a man learned in navigation, and skilful in making charts and instruments.

The effects of this establishment were soon apparent. All that was known relative to geography and navigation was gathered together and reduced to system. A vast improvement took place in maps, The compass was also brought into more general use, especially among the Portuguese, rendering the mariner more bold and venturous, by enabling him to navigate in the most gloomy day and in the darkest night. Encouraged by these advantages, and stimulated by the munificence of Prince Henry, the Portuguese marine became signalized for the hardihood of its enterprises and the extent of its discoveries. Cape Bojador was doubled; the region of the tropics penetrated, and divested of its fancied terrors; the greater part of the African coast, from Cape Blanco to Cape de Verde, explored; and the Cape de Verde and Azore islands, which lay three hundred leagues distant from the continent, were rescued from the oblivious empire of the ocean.

To secure the quiet prosecution and full enjoyment of his discoveries, Henry obtained the protection of a papal bull, granting to the crown of Portugal sovereign authority over all the lands it might discover in the Atlantic, to India inclusive, with plenary indulgence to all who should die in these expeditions; at the same time menacing, with the terrors of the church, all who should interfere in these Christian conquests.

Henry died on the 13th of November, 1473, without accomplishing the great object of his ambition. It was not until many years afterward that Vasco de Gama, pursuing with a Portuguese fleet the track he had pointed out, realized his anticipations by doubling the Cape of Good Hope, sailing along the southern coast of India, and thus opening a highway for commerce to the opulent regions of the East. Henry, however, lived long enough to reap some of the richest rewards of a great and good mind. He beheld, through his means, his native country in a grand and active career of prosperity. The discoveries of the Portuguese were the wonder and admiration of the fifteenth century, and Portugal, from being one of the least among nations, suddenly rose to be one of the most important.