Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

"The Life Of George Washington" is a monumental work on the life of one of the most famous American presidents. Originally published in five volumes between 1853 and 1859, it is a treasure chest of information on Washington and the Civil War. This work is presumeably the most intimate and fascinating biography of a man who worked his way from an Army commander to the first President of the United States. This is volume two out of five.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 671

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Life Of George Washington, Vol. 2

Washington Irving

Contents:

Washington Irving – A Biographical Primer

The Life Of George Washington, Vol. 2

Chapter I.

Chapter II.

Chapter III.

Chapter IV.

Chapter V.

Chapter VI.

Chapter VII.

Chapter VIII.

Chapter IX

Chapter X.

Chapter XI.

Chapter XII.

Chapter XIII.

Chapter XIV.

Chapter XV.

Chapter XVI.

Chapter XVII.

Chapter XVIII.

Chapter XIX.

Chapter XX.

Chapter XXI.

Chapter XXII.

Chapter XXIII.

Chapter XXIV.

Chapter XXV.

Chapter XXVI.

Chapter XXVII.

Chapter XXVIII.

Chapter XXIX.

Chapter XXX.

Chapter XXXI.

Chapter XXXII.

Chapter XXXIII.

Chapter XXXIV.

Chapter XXXV.

Chapter XXXVI.

Chapter XXXVII.

Chapter XXXVIII.

Chapter XXXIX.

Chapter XL.

Chapter XLI.

Chapter XLII.

Chapter XLIII.

Chapter XLIV.

Chapter XLV.

Chapter XLVI.

The Life Of George Washington, Vol. 2, W. Irving

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Germany

Edited and revised by Juergen Beck.

ISBN: 9783849642174

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

www.facebook.com/jazzybeeverlag

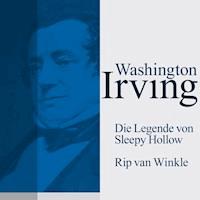

Washington Irving – A Biographical Primer

Washington Irving (1783-1859), American man of letters, was born at New York on the 3rd of April 1783. Both his parents were immigrants from Great Britain, his father, originally an officer in the merchant service, but at the time of Irving's birth a considerable merchant, having come from the Orkneys, and his mother from Falmouth. Irving was intended for the legal profession, but his studies were interrupted by an illness necessitating a voyage to Europe, in the course of which he proceeded as far as Rome, and made the acquaintance of Washington Allston. He was called to the bar upon his return, but made little effort to practice, preferring to amuse himself with literary ventures. The first of these of any importance, a satirical miscellany entitled Salmagundi, or the Whim-Whams andOpinions of Launcelot Langstaff and others, written in conjunction with his brother William and J. K. Paulding, gave ample proof of his talents as a humorist. These were still more conspicuously displayed in his next attempt, A History of New York from theBeginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by “Diedrich Knickerbocker” (2 vols., New York, 1809). The satire of Salmagundi had been principally local, and the original design of “Knickerbocker's” History was only to burlesque a pretentious disquisition on the history of the city in a guidebook by Dr Samuel Mitchell. The idea expanded as Irving proceeded, and he ended by not merely satirizing the pedantry of local antiquaries, but by creating a distinct literary type out of the solid Dutch burgher whose phlegm had long been an object of ridicule to the mercurial Americans. Though far from the most finished of Irving's productions, “Knickerbocker” manifests the most original power, and is the most genuinely national in its quaintness and drollery. The very tardiness and prolixity of the story are skillfully made to heighten the humorous effect.

Upon the death of his father, Irving had become a sleeping partner in his brother's commercial house, a branch of which was established at Liverpool. This, combined with the restoration of peace, induced him to visit England in 1815, when he found the stability of the firm seriously compromised. After some years of ineffectual struggle it became bankrupt. This misfortune compelled Irving to resume his pen as a means of subsistence. His reputation had preceded him to England, and the curiosity naturally excited by the then unwonted apparition of a successful American author procured him admission into the highest literary circles, where his popularity was ensured by his amiable temper and polished manners. As an American, moreover, he stood aloof from the political and literary disputes which then divided England. Campbell, Jeffrey, Moore, Scott, were counted among his friends, and the last-named zealously recommended him to the publisher Murray, who, after at first refusing, consented (1820) to bring out The Sketch Book ofGeoffrey Crayon, Gent. (7 pts., New York, 1819-1820). The most interesting part of this work is the description of an English Christmas, which displays a delicate humor not unworthy of the writer's evident model Addison. Some stories and sketches on American themes contribute to give it variety; of these Rip van Winkle is the most remarkable. It speedily obtained the greatest success on both sides of the Atlantic. Bracebridge Hall, or the Humourists (2 vols., New York), a work purely English in subject, followed in 1822, and showed to what account the American observer had turned his experience of English country life. The humor is, nevertheless, much more English than American. Tales of a Traveller (4 pts.) appeared in 1824 at Philadelphia, and Irving, now in comfortable circumstances, determined to enlarge his sphere of observation by a journey on the continent. After a long course of travel he settled down at Madrid in the house of the American consul Rich. His intention at the time was to translate the Coleccionde los Viajes y Descubrimientos (Madrid, 1825-1837) of Martin Fernandez de Navarrete; finding, however, that this was rather a collection of valuable materials than a systematic biography, he determined to compose a biography of his own by its assistance, supplemented by independent researches in the Spanish archives. His History of the Life and Voyages ofChristopher Columbus (London, 4 vols.) appeared in 1828, and obtained a merited success. The Voyages and Discoveries ofthe Companions of Columbus (Philadelphia, 1831) followed; and a prolonged residence in the south of Spain gave Irving materials for two highly picturesque books, A Chronicle of theConquest of Granada from the MSS. of [an imaginary] FrayAntonio Agapida (2 vols., Philadelphia, 1829), and The Alhambra:a series of tales and sketches of the Moors and Spaniards (2 vols., Philadelphia, 1832). Previous to their appearance he had been appointed secretary to the embassy at London, an office as purely complimentary to his literary ability as the legal degree which he about the same time received from the university of Oxford.

Returning to the United States in 1832, after seventeen years' absence, he found his name a household word, and himself universally honored as the first American who had won for his country recognition on equal terms in the literary republic. After the rush of fêtes and public compliments had subsided, he undertook a tour in the western prairies, and returning to the neighborhood of New York built for himself a delightful retreat on the Hudson, to which he gave the name of “Sunnyside.” His acquaintance with the New York millionaire John Jacob Astor prompted his next important work — Astoria (2 vols., Philadelphia, 1836), a history of the fur-trading settlement founded by Astor in Oregon, deduced with singular literary ability from dry commercial records, and, without labored attempts at word-painting, evincing a remarkable faculty for bringing scenes and incidents vividly before the eye. TheAdventures of Captain Bonneville (London and Philadelphia, 1837), based upon the unpublished memoirs of a veteran explorer, was another work of the same class. In 1842 Irving was appointed ambassador to Spain. He spent four years in the country, without this time turning his residence to literary account; and it was not until two years after his return that Forster's life of Goldsmith, by reminding him of a slight essay of his own which he now thought too imperfect by comparison to be included among his collected writings, stimulated him to the production of his Life of Oliver Goldsmith, with Selections fromhis Writings (2 vols., New York, 1849). Without pretensions to original research, the book displays an admirable talent for employing existing material to the best effect. The same may be said of The Lives of Mahomet and his Successors (New York, 2 vols., 1840-1850). Here as elsewhere Irving correctly discriminated the biographer's province from the historian's, and leaving the philosophical investigation of cause and effect to writers of Gibbon's caliber, applied himself to represent the picturesque features of the age as embodied in the actions and utterances of its most characteristic representatives. His last days were devoted to his Life of George Washington (5 vols., 1855-1859, New York and London), undertaken in an enthusiastic spirit, but which the author found exhausting and his readers tame. His genius required a more poetical theme, and indeed the biographer of Washington must be at least a potential soldier and statesman. Irving just lived to complete this work, dying of heart disease at Sunnyside, on the 28th of November 1859.

Although one of the chief ornaments of American literature, Irving is not characteristically American. But he is one of the few authors of his period who really manifest traces of a vein of national peculiarity which might under other circumstances have been productive. “Knickerbocker's” History of NewYork, although the air of mock solemnity which constitutes the staple of its humor is peculiar to no literature, manifests nevertheless a power of reproducing a distinct national type. Had circumstances taken Irving to the West, and placed him amid a society teeming with quaint and genial eccentricity, he might possibly have been the first Western humorist, and his humor might have gained in depth and richness. In England, on the other hand, everything encouraged his natural fastidiousness; he became a refined writer, but by no means a robust one. His biographies bear the stamp of genuine artistic intelligence, equally remote from compilation and disquisition. In execution they are almost faultless; the narrative is easy, the style pellucid, and the writer's judgment nearly always in accordance with the general verdict of history. Without ostentation or affectation, he was exquisite in all things, a mirror of loyalty, courtesy and good taste in all his literary connexions, and exemplary in all the relations of domestic life. He never married, remaining true to the memory of an early attachment blighted by death.

The principal edition of Irving' s works is the “Geoffrey Crayon,” published at New York in 1880 in 26 vols. His Life and Letters was published by his nephew Pierre M. Irving (London, 1862-1864, 4 vols.; German abridgment by Adolf Laun, Berlin, 1870, 2 vols.) There is a good deal of miscellaneous information in a compilation entitled Irvingiana (New York, 1860); and W. C. Bryant's memorial oration, though somewhat too uniformly laudatory, may be consulted with advantage. It was republished in Studies of Irvine (1880) along with C. Dudley Warner's introduction to the “Geoffrey Crayon” edition, and Mr. G. P. Putnam's personal reminiscences of Irving, which originally appeared in the Atlantic Monthly. See also Washington Irving (1881), by C. D. Warner, in the “American Men of Letters” series; H. R. Haweis, American Humourists (London, 1883).

TheLife Of George Washington, Vol. 2

Chapter I.

On the 3rd of July, the morning after his arrival at Cambridge, Washington took formal command of the army. It was drawn up on the Common about half a mile from head-quarters. A multitude had assembled there, for as yet military spectacles were novelties, and the camp was full of visitors, men, women and children, from all parts of the country, who had relatives among the yeoman soldiery.

An ancient elm is still pointed out, under which Washington, as he arrived from head-quarters accompanied by General Lee and a numerous suite, wheeled his horse, and drew his sword as commander-in-chief of the armies. We have cited the poetical description of him furnished by the pen of Mrs. Adams; we give her sketch of his military compeer — less poetical, but no less graphic.

" General Lee looks like a careless, hardy veteran; and by his appearance brought to my mind his namesake, Charles XII. of Sweden. The elegance of his pen far exceeds that of his person."

Accompanied by this veteran campaigner, on whose military judgment he had great reliance, Washington visited the different American posts, and rode to the heights, commanding views over Boston and its environs, being anxious to make himself acquainted with the strength and relative position of both armies: and here we will give a few particulars concerning the distinguished commanders with whom he was brought immediately in competition.

Congress, speaking of them reproachfully, observed, "Three of England's most experienced generals are sent to wage war with their fellow-subjects." The first here alluded to was the Honorable William Howe, next in command to Gage. He was a man of a fine presence, six feet high, well proportioned, and of graceful deportment. He is said to have been not unlike Washington in appearance, though wanting his energy and activity. He lacked also his air of authority; but affability of manners, and a generous disposition, made him popular with both officers and soldiers.

There was a sentiment in his favor even among Americans at the time when he arrived at Boston. It was remembered that he was brother to the gallant and generous youth, Lord Howe, who fell in the flower of his days, on the banks of Lake George, and whose untimely death had been lamented throughout the colonies. It was remembered that the general himself had won reputation in the same campaign, commanding the light infantry under Wolfe, on the famous plains of Abraham. A mournful feeling had therefore gone through the country, when General Howe was cited as one of the British commanders, who had most distinguished themselves in the bloody battle of Bunker's Hill. Congress spoke of it with generous sensibility, in their address to the people of Ireland already quoted. " America is amazed," said they, " to find the name of Howe on the catalogue of her enemies — she loved his brother!"

General Henry Clinton, the next in command, was grandson of the Earl of Lincoln, and son of George Clinton, who had been Governor of the Province of New York for ten years, from 1743. The general had seen service on the continent in the Seven Years' War. He was of short stature, and inclined to corpulency; with a full face, and prominent nose. His manners were reserved, and altogether he was in strong contrast with Howe, and by no means so popular.

Burgoyne, the other British general of note, was natural son of Lord Bingley, and had entered the army at an early age. While yet a subaltern, he had made a runaway match with a daughter of the Earl of Derby, who threatened never to admit the offenders to his presence. In 1758, Burgoyne was a Lieutenant colonel of light dragoons. In 1761, he was sent with a force to aid the Portuguese against the Spaniards, joined the army commanded by the Count de la Lippe, and signalized himself by surprising and capturing the town of Alcantara. He had since been elected to Parliament for the borough of Middlesex, and displayed considerable parliamentary talents. In 1772, he was made a Major-general. His taste, wit, and intelligence, and his aptness at devising and promoting elegant amusements, made him for a time a leader in the gay world; though Junius accuses him of unfair practices at the gaming table. His reputation for talents and services had gradually mollified the heart of Iris father-in-law, the Earl of Derby. In 1774, he gave celebrity to the marriage of a son of the Earl with Lady Betty Hamilton, by producing an elegant dramatic trifle, entitled, " The Maid of the Oaks," afterwards performed at Drury Lane, and honored with a biting sarcasm by Horace Walpole. " There is a new puppet-show at Drury Lane," writes the wit, " as fine as the scenes can make it, and as dull as the author could not help making it."

It is but justice to Burgoyne's memory to add, that, in after years, he produced a dramatic work, "The Heiress," which extorted even Walpole's approbation, who pronounced it the genteelest comedy in the English language.

Such were the three British commanders at Boston, who were considered especially formidable; and they had with them eleven thousand veteran troops, well appointed and well disciplined.

In visiting the different posts, Washington halted for a time at Prospect Hill, which, as its name denotes, commanded a wide view over Boston and the surrounding country. Here Putnam had taken his position after the battle of Bunker's Hill, fortifying himself with works which he deemed impregnable; and here the veteran was enabled to point out to the commander-in-chief, and to Lee, the main features of the belligerent region, which lay spread out like a map before them.

Bunker's Hill was but a mile distant to the west; the British standard floating as if in triumph on its summit. The main force under General Howe was entrenching itself strongly about half a mile beyond the place of the recent battle. Scarlet uniforms gleamed about the hill; tents and marquees whitened its sides. All up there was bright, brilliant, and triumphant. At the base of the hill lay Charlestown in ashes, " nothing to be seen of that fine town but chimneys and rubbish."

Howe's sentries extended a hundred and fifty yards beyond the neck or isthmus, over which the Americans retreated after the battle. Three floating batteries in Mystic River commanded this isthmus, and a twenty-gun ship was anchored between the peninsula and Boston.

General Gage, the commander-in-chief, still had his head-quarters in the town, but there were few troops there besides Burgoyne's light-horse. A large force, however, was entrenched south of the town on the neck leading to Roxbury, — the only entrance to Boston by land.

The American troops were irregularly distributed in a kind of semicircle eight or nine miles in extent; the left resting on Winter Hill, the most northern post; the right extending on the south to Roxbury and Dorchester Neck.

Washington reconnoitred the British posts from various points of view. Every thing about them was in admirable order. The works appeared to be constructed with military science, the troops to be in a high state of discipline; the American camp, on the contrary, disappointed him. He had expected to find eighteen or twenty thousand men under arms; there were not much more than fourteen thousand. He had expected to find some degree of system and discipline, whereas all were raw militia. He had expected to find works scientifically constructed, and proofs of knowledge and skill in engineering; whereas, what he saw of the latter, was very imperfect, and confined to the mere manual exercise of cannon. There was abundant evidence of aptness at trenching and throwing up rough defences; and in that way General Thomas had fortified Roxbury Neck, and Putnam had strengthened Prospect Hill. But the semicircular line which linked the extreme posts, was formed of rudely-constructed works, far too extensive for the troops which were at hand to man them.

Within this attenuated semicircle, the British forces lay concentrated and compact; and having command of the water, might suddenly bring their main strength to bear upon some weak point, force it, and sever the American camp.

In fact, when we consider the scanty, ill-conditioned and irregular force which had thus stretched itself out to beleaguer a town and harbor defended by ships and floating batteries, and garrisoned by eleven thousand strongly posted veterans, we are at a loss whether to attribute its hazardous position to ignorance, or to that daring self-confidence, which at times, in our military history, has snatched success in defiance of scientific rule. It was revenge for the slaughter at Lexington which, we are told, first prompted the investment of Boston. "The universal voice," says a contemporary, "is, starve them out. Drive them from the town, and let His Majesty's ships be their only place of refuge."

In riding throughout the camp, Washington observed that nine thousand of the troops belonged to Massachusetts; the rest were from other provinces. They were encamped in separate bodies, each with its own regulations, and officers of its own appointment. Some had tents, others were in barracks, and others sheltered themselves as best they might. Many were sadly in want of clothing, and all, said Washington, were strongly imbued with the spirit of insubordination, which they mistook for independence.

A chaplain of one of the regiments has left on record a graphic sketch of this primitive army of the Revolution. " It is very diverting," writes he, " to walk among the camps. They are as different in their forms, as the owners are in their dress; and every tent is a portraiture of the temper and taste of the persons who encamp in it. Some are made of boards, and some are made of sail-cloth; some are partly of one, and partly of the other. Again others are made of stone and turf, brick and brush. Some are thrown up in a hurry, others curiously wrought with wreaths and withes."

One of the encampments, however, was in striking contrast with the rest, and might vie with those of the British for order and exactness. Here were tents and marquees pitched in the English style; soldiers well drilled and well equipped; every thing had an air of discipline and subordination. It was a body of Rhode Island troops, which had been raised, drilled, and brought to the camp by Brigadier-general Greene, of that province, whose subsequent renown entitles him to an introduction to the reader.

Nathaniel Greene was born in Rhode Island, on the 26th of May, 1742. His father was a miller, an anchor-smith, and a Quaker preacher. The waters of the Potowhammet turned the wheels of the mill, and raised the ponderous sledge-hammer of the forge. Greene, in his boyhood, followed the plough, and occasionally worked at the forge of his father. His education was of an ordinary kind; but having an early thirst for knowledge, he applied himself sedulously to various studies, while subsisting by the labor of his hands. Nature had endowed him with quick parts, and a sound judgment, and his assiduity was crowned with success. He became fluent and instructive in conversation, and his letters, still extant, show that he held an able pen.

In the late turn of public affairs, he had caught the belligerent spirit prevalent throughout the country. Plutarch and Caesar's Commentaries became his delight. He applied himself to military studies, for which he was prepared by some knowledge of mathematics. His ambition was to organize and discipline a corps of militia to which he belonged. For this purpose, during a visit to Boston, he had taken note of every thing about the discipline of the British troops. In the month of May, he had been elected commander of the Rhode Island contingent of the army of observation, and in June had conducted to the lines before Boston, three regiments, whose encampment we have just described, and who were pronounced the best disciplined and appointed troops in the army.

Greene made a soldier-like address to Washington, welcoming him to the camp. His appearance and manner were calculated to make a favorable impression. He was about thirty-nine years of age, nearly six feet high, well built, and vigorous, with an open, animated, intelligent countenance, and a frank, manly demeanor. He may be said to have stepped at once into the confidence of the commander-in-chief, which he never forfeited, but became one of his most attached, faithful, and efficient coadjutors throughout the war.

Having taken his survey of the army, Washington wrote to the President of Congress, representing its various deficiencies, and, among other things, urging the appointment of a commissary-general, a quartermaster-general, a commissary of musters, and a commissary of artillery. Above all things, he requested a supply of money as soon as possible. " I find myself already much embarrassed for want of a military chest."

In one of his recommendations, we have an instance of frontier expediency, learnt in his early campaigns. Speaking of the ragged condition of the army, and the difficulty of procuring the requisite kind of clothing, he advises that a number of hunting-shirts, not less than ten thousand, should be provided, as being the cheapest and quickest mode of supplying this necessity. " I know nothing in a speculative view more trivial " observes he, " yet which, if put in practice, would have a happier tendency to unite the men, and abolish those provincial distinctions that lead to jealousy and dissatisfaction."

Among the troops most destitute, were those belonging to Massachusetts, which formed the larger part of the army. Washington made a noble apology for them. " This unhappy and devoted province," said he, " has been so long in a state of anarchy, and the yoke has been laid so heavily on it, that great allowances are to be made for troops raised under such circumstances. The deficiency of numbers, discipline, and stores, can only lead to this conclusion, that their spirit has exceeded their strength."

This apology was the more generous, coming from a Southerner; for there was a disposition among the Southern officers to regard the Eastern troops disparagingly. But Washington already felt as commander-in-chief, who looked with an equal eye on all; or rather as a true patriot, who was above all sectional prejudices.

One of the most efficient co-operators of Washington at this time, and throughout the war, was Jonathan Trumbull, the Governor of Connecticut. He was a well educated man, experienced in public business, who had sat for many years in the legislative councils of his native province. Misfortune had cast him down from affluence, at an advanced period of life, but had not subdued his native energy. He had been one of the leading spirits of the Revolution, and the only colonial governor who, at its commencement, proved true to the popular cause. He was now sixty-five years of age, active, zealous, devout, a patriot of the primitive New England stamp, whose religion sanctified his patriotism. A letter addressed by him to Washington, just after the latter had entered upon the command, is worthy of the purest days of the Covenanters. " Congress," writes he, " have, with one united voice, appointed you to the high station you possess. The Supreme Director of all events hath caused a wonderful union of hearts and counsels to subsist among us.

" Now, therefore, be strong, and very courageous. May the God of the armies of Israel shower down the blessings of his Divine providence on you; give you wisdom and fortitude, cover your head in the day of battle and danger, add success, convince our enemies of their mistaken measures, and that all their attempts to deprive these colonies of their inestimable constitutional rights and liberties, are injurious and vain."

NOTE:

We are obliged to Professor Felton, of Cambridge, for correcting an error in our first volume in regard to Washington's bead-quarters, and for some particulars concerning a house, associated with the history and literature of our country.

The house assigned to Washington for headquarters, was that of the president of the Provincial Congress, not of the University. It had been one of those Tory mansions noticed by the Baroness Reidesel, in her mention of Cambridge. " Seven families, who were connected by relationship, or lived in great intimacy, had here farms, gardens, and splendid mansions, and not far off, orchards; and the buildings were at a quarter of a mile distant from each other. The owners had been in the habit of assembling every afternoon in one or other of these houses, and of diverting themselves with music or dancing; and lived in affluence, in good humor, and without care, until this unfortunate war dispersed them, and transformed all these houses into solitary abodes."

The house in question was confiscated by Government. It stood on the Watertown road, about half a mile west of the college, and has long been known as the Cragie House, from the name of Andrew Cragie, a wealthy gentleman, who purchased it after the war, and revived its former hospitality. He is said to have acquired great influence among the leading members of the " great and general court," by dint of jovial dinners. He died long since, but his widow survived until within fifteen years. She was a woman of much talent and singularity. She refused to have the canker worms destroyed, when they were making sad ravages among the beautiful trees on the lawn before the house. " "We are all worms," said she, " and they have as good a right here as I have." The consequence was that more than half of the trees perished.

The Cragie House is associated with American literature through some of its subsequent occupants. Mr. Edward Everett resided in it the first year or two after his marriage. Later, Mr. Jared Sparks, during part of the time that he was preparing his collection of Washington's writings; editing a volume or two of his letters in the very room from which they were written. Next came Mr. Worcester, author of the pugnacious dictionary, and of many excellent books, and lastly Longfellow, the poet, who having married the heroine of Hyperion, purchased the house of the heirs of Mr. Cragie, and refitted it.

Chapter II.

The justice and impartiality of Washington were called into exercise as soon as he entered upon his command, in. allaying discontents among his general officers, caused by the recent appointments and promotions made by the Continental Congress. General Spencer was so offended that Putnam should be promoted over his head, that he left the army, without visiting the commander-in-chief; but was subsequently induced to return. General Thomas felt aggrieved by being outranked by the veteran Pomeroy; the latter, however, declining to serve, he found himself senior brigadier, and was appeased.

The sterling merits of Putnam soon made every one acquiesce in his promotion. There was a generosity and buoyancy about the brave old man that made him a favorite throughout the army; especially with the younger officers, who spoke of him familiarly and fondly as " Old Put;" a soubriquet by which he is called even in one of the private letters of the commander-in-chief.

The Congress of Massachusetts manifested considerate liberality with respect to head-quarters. According to their minutes, a committee was charged to procure a steward, a housekeeper, and two or three women cooks; Washington, no doubt, having brought with him none but the black servants who had accompanied him to Philadelphia, and who were but little fitted for New England housekeeping. His wishes were to be consulted in regard to the supply of his table. This his station, as commander-in-chief, required should be kept up in ample and hospitable style. Every day a number of his officers dined with him. As he was in the neighborhood of the seat of the Provincial Government, he would occasionally have members of Congress and other functionaries at his board. Though social, however, he was not convivial in his habits. He received his guests with courtesy; but his mind and time were too much occupied by grave and anxious concerns, to permit him the genial indulgence of the table. His own diet was extremely simple. Sometimes nothing but baked apples or berries, with cream and milk. He would retire early from the board, leaving an aide-de-camp or one of his officers to take his place. Colonel Mifflin was the first person who officiated as aide-de-camp. He was a Philadelphia gentleman of high respectability, who had accompanied him from that city, and received his appointment shortly after their arrival at Cambridge. The second aide-de-camp, was John Trumbull, son of the Governor of Connecticut. He had accompanied General Spencer to the camp, and had caught the favorable notice of Washington by some drawings which he had made of the enemy's works. "I now suddenly found myself," writes Trumbull, "in the family of one of the most distinguished and dignified men of the age; surrounded at his table by the principal officers of the army, and in constant intercourse with them — it was further my duty to receive company, and do the honors of the house to many of the first people of the country of both sexes." Trumbull was young, and unaccustomed to society, and soon found himself, he says, unequal to the elegant duties of his situation; he gladly exchanged it, therefore, for that of major of brigade.

The member of Washington's family most deserving of mention at present, was his secretary, Mr. Joseph Reed. With this gentleman he had formed an intimacy in the course of his visits to Philadelphia, to attend the sessions of the Continental Congress. Mr. Reed was an accomplished man, had studied law in America, and at the Temple in London, and had gained a high reputation at the Philadelphia bar. In the dawning of the Revolution he had embraced the popular cause, and carried on a correspondence with the Earl of Dartmouth, endeavoring to enlighten that minister on the subject of colonial affairs. He had since been highly instrumental in rousing the Philadelphians to co-operate with the patriots of Boston. A sympathy of views and feelings had attached him to Washington, and induced him to accompany him to the camp. He had no definite purpose when he left home, and his friends in Philadelphia were surprised, on receiving a letter from him written from Cambridge, to find that he had accepted the post of secretary to the commander-in-chief.

They expostulated with him by letter. That a man in the thirty-fifth year of his age, with a lucrative profession, a young wife and growing family, and a happy home, should suddenly abandon all to join the hazardous fortunes of a revolutionary camp, appeared to them the height of infatuation. They remonstrated on the peril of the step. " I have no inclination," replied Reed, " to be hanged for half treason. When a subject draws his sword against his prince, he must cut his way through, if he means to sit down in safety. I have taken too active a part in what may be called the civil part of opposition, to renounce, without disgrace, the public cause when it seems to lead to danger; and have a most sovereign contempt for the man who can plan measures he has not the spirit to execute."

Washington has occasionally been represented as cold and reserved; yet his intercourse with Mr. Reed is a proof to the contrary. His friendship towards him was frank and cordial, and the confidence he reposed in him full and implicit. Reed, in fact, became, in a little time, the intimate companion of his thoughts, his bosom counselor. He felt the need of such a friend in the present exigency, placed as he was, in a new and untried situation, and having to act with persons hitherto unknown to him.

In military matters, it is true he had a shrewd counselor in General Lee; but Lee was a wayward character; a cosmopolite, without attachment to country, somewhat splenetic, and prone to follow the bent of his whims and humors, which often clashed with propriety and sound policy. Reed on the contrary, though less informed on military matters, had a strong common sense, unclouded by passion or prejudice, and a pure patriotism, which regarded every thing as it bore upon the welfare of his country.

Washington's confidence in Lee had always to be measured and guarded in matters of civil policy.

The arrival of Gates in camp, was heartily welcomed by the commander-in-chief, who had received a letter from that officer, gratefully acknowledging his friendly influence in procuring him the appointment of adjutant-general. Washington may have promised himself much cordial co-operation from him, recollecting the warm friendship professed by him when he visited at Mount Vernon, and they talked together over their early companionship in arms; but of that kind of friendship there was no further manifestation. Gates was certainly of great service, from his practical knowledge and military experience at this juncture, when the whole army had in a manner to be organized; but from the familiar intimacy of Washington he gradually estranged himself. A contemporary has accounted for this, by alleging that he was secretly chagrined at not having received the appointment of major-general, to which he considered himself well fitted by his military knowledge and experience, and which he thought Washington might have obtained for him had he used his influence with Congress. We shall have to advert to this estrangement of Gates on subsequent occasions.

The hazardous position of the army from the great extent and weakness of its lines, was what most pressed on the immediate attention of Washington; and he summoned a council of war, to take the matter into consideration. In this it was urged that, to abandon the line of works, after the great labor and expense of their construction, would be dispiriting to the troops and encouraging to the enemy, while it would expose a wide extent of the surrounding country to maraud and ravage. Beside, no safer position presented itself, on which to fall back. This being generally admitted, it was determined to hold on to the works and defend them as long as possible; and, in the mean time, to augment the army to at least twenty thousand men.

Washington now hastened to improve the defences of the camp, strengthen the weak parts of the line, and throw up additional works round the main forts. No one seconded him more effectually in this matter than General Putnam. No works were thrown up with equal rapidity to those under his superintendence. " You seem, general " said Washington, " to have the faculty of infusing your own spirit into all the workmen you employ; " — and it was the fact.

The observing chaplain already cited, gazed with wonder at the rapid effects soon produced by the labors of an army. "It is surprising," writes he, "how much work has been done. The lines are extended almost from Cambridge to Mystic River; very soon it will be morally impossible for the enemy to get between the works, except in one place, which is supposed to be left purposely unfortified, to entice the enemy out of their fortresses. Who would have thought, twelve months past, that all Cambridge and Charlestown would be covered over with American camps, and cut up into forts and entrenchments, and all the lands, fields, orchards, laid common, — horses and cattle feeding on the choicest mowing land, whole fields of corn eaten down to the ground, and large parks of well regulated forest trees cut down for fire-wood and other public uses."

Beside the main dispositions above mentioned, about seven hundred men were distributed in the small towns and villages along the coast to prevent depredations by water; and horses were kept ready saddled at various points of the widely extended lines, to convey to head-quarters intelligence of any special movement of the enemy.

The army was distributed by Washington into three grand divisions. One, forming the right wing, was stationed on the heights of Roxbury. It was commanded by Major-general Ward, who had under him Brigadier-generals Spencer and Thomas. Another, forming the left wing under Major-general Lee, having with him Brigadier-generals Sullivan and Greene, was stationed on Winter and Prospect Hills; while the centre, under Major-general Putnam and Brigadier general Heath, was stationed at Cambridge. With Putnam was encamped his favorite officer Knowlton, who had been promoted by Congress to the rank of major for his gallantry at Bunker's Hill.

At Washington's recommendation, Joseph Trumbull, the eldest son of the governor, received on the 24th of July the appointment of commissary-general of the continental army. He had already officiated with talent in that capacity in the Connecticut militia. " There is a great overturning in the camp as to order and regularity" writes the military chaplain; "new lords, new laws. The generals Washington and Lee are upon the lines every day. New orders from his excellency are read to the respective regiments every morning after prayers. The strictest government is taking place, and great distinction is made between officers and soldiers. Every one is made to know his place and keep it, or be tied up and receive thirty or forty lashes according to his crime. Thousands are at work every day from four till eleven o'clock in the morning."

Lee was supposed to have been at the bottom of this rigid discipline; the result of his experience in European campaigning. His notions of military authority were acquired in the armies of the North. Quite a sensation was, on one occasion, produced in camp by his threatening to cane an officer for unsoldierly conduct. His laxity in other matters occasioned almost equal scandal. He scoffed, we are told, " with his usual profaneness," at a resolution of Congress appointing a day of fasting and prayer, to obtain the favor of Heaven upon their cause. " Heaven" he observed, " was ever found favorable to strong battalions."

Washington differed from him in this respect. By his orders the resolution of Congress was scrupulously enforced. All labor, excepting that absolutely necessary, was suspended on the appointed day, and officers and soldiers were required to attend divine service, armed and equipped and ready for immediate action.

Nothing excited more gaze and wonder among the rustic visitors to the camp, than the arrival of several rifle companies, fourteen hundred men in all, from Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia; such stalwart fellows as Washington had known in his early campaigns. Stark hunters and bush fighters; many of them upwards of six feet high, and of vigorous frame; dressed in fringed frocks, or rifle shirts, and round hats. Their displays of sharp shooting were soon among the marvels of the camp. We are told that while advancing at quick step, they could hit a mark of seven inches diameter, at the distance of two hundred and fifty yards.

One of these companies was commanded by Captain Daniel Morgan, a native of New Jersey, whose first experience in war had been to accompany Braddock's army as a waggoner. He had since carried arms on the frontier and obtained a command. He and his riflemen in coming to the camp had marched six hundred miles in three weeks. They will be found of signal efficiency in the sharpest conflicts of the revolutionary war.

While all his forces were required for the investment of Boston, Washington was importuned by the Legislature of Massachusetts and the Governor of Connecticut, to detach troops for the protection of different points of the sea-coast, where depredations by armed vessels were apprehended. The case of New London was specified by Governor Trumbull, where Captain Wallace of the Rose frigate, with two other ships of war, had entered the harbor, landed men, spiked the cannon, and gone off threatening future visits.

Washington referred to his instructions, and consulted with his general officers and such members of the Continental Congress as happened to be in camp, before he replied to these requests; he then respectfully declined compliance.

In his reply to the General Assembly of Massachusetts, he stated frankly and explicitly the policy and system on which the war was to be conducted, and according to which he was to act as commander-in-chief. " It has been debated in Congress and settled," writes he, " that the militia, or other internal strength of each province, is to be applied for defence against those small and particular depredations, which were to be expected, and to which they were supposed to be competent. This will appear the more proper, when it is considered that every town, and indeed every part of our sea-coast, which is exposed to these depredations, would have an equal claim upon this army.

" It is the misfortune of our situation which exposes us to these ravages, and against which, in my judgment, no such temporary relief could possibly secure us. The great advantage the enemy have of transporting troops, by being masters of the sea, will enable them to harass us by diversions of this kind; and should we be tempted to pursue them, upon every alarm, the army must either be so weakened as to expose it to destruction, or a great part of the coast be still left unprotected. Nor, indeed, does it appear to me that such a pursuit would be attended with the least effect. The first notice of such an excursion would be its actual execution, and long before any troops could reach the scene of action, the enemy would have an opportunity to accomplish their purpose and retire. It would give me great pleasure to have it in my power to extend protection and safety to every individual; but the wisdom of the General Court will anticipate me on the necessity of conducting our operations on a general and impartial scale, so as to exclude any just cause of complaint and jealousy."

His reply to the Governor of Connecticut was to the same effect. " I am by no means insensible to the situation of the people on the coast. I wish I could extend protection to all, but the numerous detachments necessary to remedy the evil would amount to a dissolution of the army, or make the most important operations of the campaign depend upon the piratical expeditions of two or three men-of-war and transports."

His refusal to grant the required detachments gave much dissatisfaction in some quarters, until sanctioned and enforced by the Continental Congress. All at length saw and acquiesced in the justice and wisdom of his decision. It was in fact a vital question, involving the whole character and fortune of the war; and it was acknowledged that he met it with a forecast and determination befitting a commander-in-chief.

Chapter III.

The great object of Washington, at present, was to force the enemy to come out of Boston and try a decisive action. His lines had for some time cut off all communication of the town with the country, and he had caused the live stock within a considerable distance of the place to be driven back from the coast, out of reach of the men-of-war's boats. Fresh provisions and vegetables were consequently growing more and more scarce and extravagantly dear, and sickness began to prevail. " I have done and shall do every thing in my power to distress them," writes he to his brother John Augustine. " The transports have all arrived, and then whole reinforcement is landed, so that I see no reason why they should not, if they ever attempt it, come boldly out and put the matter to issue at once."

"We are in the strangest state in the world," writes a lady from Boston, " surrounded on all sides. The whole country is in arms and entrenched. We are deprived of fresh provisions, subject to continual alarms and cannonadings, the Provincials being very audacious and advancing to our lines, since the arrival of Generals Washington and Lee to command them."

At this critical juncture, when Washington was pressing the siege, and endeavoring to provoke a general action, a startling fact came to light; the whole amount of powder in the camp would not furnish more than nine cartridges to a man!

A gross error had been made by the committee of supplies when Washington, on taking command, had required a return of the ammunition. They had returned the whole amount of powder collected by the province, upwards of three hundred barrels; without stating what had been expended. The blunder was detected on an order being issued for a new supply of cartridges. It was found there were but thirty-two barrels of powder in store.

This was an astounding discovery. Washington instantly dispatched letters and expresses to Rhode Island, the Jerseys, Ticonderoga and elsewhere, urging immediate supplies of powder and lead; no quantity, however small, to be considered beneath notice. In a letter to Governor Cooke of Rhode Island, he suggested that an armed vessel of that province might be sent to seize upon a magazine of gunpowder, said to be in a remote part of the Island of Bermuda. " I am very sensible," writes he, " that at first view the project may appear hazardous, and its success must depend on the concurrence of

Enterprises which appear chimerical, often prove successful from that very circumstance. Common sense and prudence will suggest vigilance and care, where the danger is plain and obvious; but where little danger is apprehended, the more the enemy will be unprepared, and, consequently, there is the fairest prospect of success."

Day after day elapsed without the arrival of any supplies; for in these irregular times, the munitions of war were not readily procured. It seemed hardly possible that the matter could be kept concealed from the enemy. Their works on Bunker's Hill commanded a full view of those of the Americans on Winter and Prospect Hills. Each camp could see what was passing in the other. The sentries were almost near enough to converse. There was furtive intercourse occasionally between the men. In this critical state, the American camp remained for a fortnight; the anxious commander incessantly apprehending an attack. At length a partial supply from the Jerseys put an end to this imminent risk. Washington's secretary, Reed, who had been the confidant of his troubles and anxieties, gives a vivid expression of his feelings on the arrival of this relief. " I can hardly look back, without shuddering, at our situation before this increase of our stock. Stock did I say? It was next to nothing. Almost the whole powder of the army was in the cartridge-boxes."

It is thought that, considering the clandestine intercourse carried on between the two camps, intelligence of this deficiency of ammunition on the part of the besiegers must have been conveyed to the British commander; but that the bold face with which the Americans continued to maintain their position, made him discredit it.

Notwithstanding the supply from the Jerseys, there was not more powder in camp than would serve the artillery for one day of general action. None, therefore, was allowed to be wasted; the troops were even obliged to bear in silence an occasional cannonading. " Our poverty in ammunition," writes Washington, "prevents our making a suitable return."

One of the painful circumstances attending the outbreak of a revolutionary war is, that gallant men, who have held allegiance to the same government, and fought side by side under the same flag, suddenly find themselves in deadly conflict with each other. Such was the case at present in the hostile camps. General Lee, it will be recollected, had once served under General Burgoyne, in Portugal, and had won his brightest laurels when detached by that commander to surprise the Spanish camp, near the Moorish castle of Villa Velha. A soldier's friendship had ever since existed between them, and when Lee had heard at Philadelphia, before he had engaged in the American service, that his old comrade and commander was arrived at Boston, he wrote a letter to him giving his own views on the points in dispute between the colonies and the mother country, and inveighing with his usual vehemence and sarcastic point, against the conduct of the court and ministry. Before sending the letter, he submitted it to the Boston delegates and other members of Congress, and received their sanction.

Since his arrival in camp he had received a reply from Burgoyne, couched in moderate and courteous language, and proposing an interview at a designated house on Boston Neck, within the British sentries; mutual pledges to be given for each other's safety.

Lee submitted this letter to the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts, and requested their commands with respect to the proposed interview. They expressed, in reply, the highest confidence in his wisdom, discretion and integrity, but questioned whether the interview might not be regarded by the public with distrust; "a people contending for their liberties being naturally disposed to jealousy. They suggested, therefore, as a means of preventing popular misconception, that Lee on seeking the interview, should be accompanied by Mr. Elbridge Gerry; or that the advice of a council of war should be taken in a matter of such apparent delicacy.

Lee became aware of the surmises that might be awakened by the proposed interview, and wrote a friendly note to Burgoyne declining it.

A correspondence of a more important character took place between Washington and General Gage. It was one intended to put the hostile services on a proper footing. A strong disposition had been manifested among the British officers to regard those engaged in the patriot cause as malefactors, outlawed from the courtesies of chivalric warfare. Washington was determined to have a full understanding on this point. He was peculiarly sensitive with regard to Gage. They had been companions in arms in their early days; but Gage might now affect to look down upon him as the chief of a rebel army. Washington took an early opportunity to let him know, that he claimed to be the commander of a legitimate force, engaged in a legitimate cause, and that both himself and his army were to be treated on a footing of perfect equality. The correspondence arose from the treatment of several American officers.

" I understand," writes Washington to Gage, " that the officers engaged in the cause of liberty and their country, who by the fortune of war have fallen into your hands, have been thrown indiscriminately into a common jail, appropriated to felons; that no consideration has been had for those of the most respectable rank, when languishing with wounds and sickness, and that some have been amputated in this unworthy situation. Let your opinion, sir, of the principles which actuate them, be what it may, they suppose that they act from the noblest of all principles, love of freedom and their country. But political principles, I conceive, are foreign to this point. The obligations arising from the rights of humanity and claims of rank are universally binding and extensive, except in case of retaliation. These, I should have hoped, would have dictated a more tender treatment of those individuals whom chance or war had put in your power. Nor can I forbear suggesting its fatal tendency to widen that unhappy breach which you, and those ministers under whom you act, have repeatedly declared your wish to see for ever closed. My duty now makes it necessary to apprise you that, for the future, I shall regulate all my conduct towards those gentlemen who are, or may be, in our possession, exactly by the rule you shall observe towards those of ours, now in your custody.

" If severity and hardships mark the line of your conduct, painful as it may be to me, your prisoners will feel its effects. But if kindness and humanity are shown to us, I shall with pleasure consider those in our hands only as unfortunate, and they shall receive from me that treatment to which the unfortunate are ever entitled."

The following are the essential parts of a letter from General Gage in reply.

" Sir, — To the glory of civilized nations, humanity and war have been compatible, and humanity to the subdued has become almost a general system. Britons, ever pre-eminent in mercy, have outgone common examples, and overlooked the criminal in the captive. Upon these principles your prisoners, whose lives by the law of the land are destined to the cord, have hitherto been treated with care and kindness, and more comfortably lodged than the King's troops in the hospitals; indiscriminately it is true, for I acknowledge no rank that is not derived from the King.

"My intelligence from your army would justify severe recriminations. I understand there are of the King's faithful subjects, taken some time since by the rebels, laboring, like negro slaves to gain their daily subsistence, or reduced to the wretched alternative to perish by famine or take arms against their King and country. Those who have made the treatment of the prisoners in my hands, or of your other friends in Boston, a pretence for such measures, found barbarity upon falsehood.

" I would willingly hope, sir, that the sentiments of liberality which I have always believed you to possess, will be exerted to correct these misdoings. Be temper rate in political disquisition; give free operation to truth, and punish those who deceive and misrepresent; and not only the effects, but the cause, of this unhappy conflict will be removed. Should those, under whose usurped authority you act, control such a disposition, and dare to call severity retaliation; to God, who knows all hearts, be the appeal of the dreadful consequences," &c.

There were expressions in the foregoing letter well calculated to rouse indignant feelings in the most temperate bosom. Had Washington been as readily moved to transports of passion as some are pleased to represent him, the rebel and the cord might readily have stung him to fury; but with him, anger was checked in its impulses by higher energies, and reined in to give a grander effect to the dictates of his judgment. The following was his noble and dignified reply to General Gage:

" I addressed you, sir, on the 11th instant in terms which gave the fairest scope for that humanity and politeness which were supposed to form a part of your character. I remonstrated with you on the* unworthy treatment shown to the officers and citizens of America, whom the fortune of war, chance, or a mistaken confidence had thrown into your hands. Whether British or American mercy, fortitude and patience, are most pre-eminent; whether our virtuous citizens, whom the hand of tyranny has forced into arms to defend their wives, their children and their property, or the merciless instruments of lawless domination, avarice, and; revenge, best deserve the appellation of rebels, and the punishment of that cord, which your affected clemency has forborne to inflict; whether the authority under which I act is usurped, or founded upon the genuine principles of liberty, were altogether foreign to the subject. I purposely avoided all political disquisition; nor shall I now avail myself of those advantages which the sacred cause of my country, of liberty, and of human nature give me over you; much less shall I stoop to retort and invective; but the intelligence you say you have received from our army requires a reply. I have taken time, sir, to make a strict inquiry, and find it has not the least foundation in truth. Not only your officers and soldiers have been treated with the tenderness due to fellow-citizens and brethren, but even those execrable parricides, whose counsels and aid have deluged their country with blood, have been protected from the fury of a justly enraged people. Tar from compelling or permitting their assistance, I am embarrassed with the numbers, who crowd to our camp, animated with the purest principles of virtue and love to their country.

" You affect, sir, to despise all rank not derived from the same source with your own. I cannot conceive one more honorable, than that which flows from the uncorrupted choice of a brave and free people, the purest source and original fountain of all power. Par from making it a plea for cruelty, a mind of true magnanimity and enlarged ideas would comprehend and respect it.

" What may have been the ministerial views which have precipitated the present crisis, Lexington, Concord and Charlestown, can best declare. May that God, to whom you, too, appeal, judge between America and you. Under his providence, those who influence the councils of America, and all the other inhabitants of the united colonies, at the hazard of their lives, are determined to hand down to posterity those just and invaluable privileges which they received from their ancestors.

" I shall now, sir, close my correspondence with you, perhaps for ever. If your officers, our prisoners, receive a treatment from me different from that which I wished to show them, they and you will remember the occasion of it."

We have given these letters of Washington almost entire, for they contain his manifesto as commander-in-chief of the armies of the Revolution; setting forth the opinions and motives by which he was governed, and the principles on which hostilities on his part would be conducted. It was planting, with the pen, that standard which was to be maintained by the sword.

In conformity with the threat conveyed in the latter part of his letter, Washington issued orders that British officers at Watertown and Cape Ann, who were at large on parole, should be confined in Northampton jail; explaining to them that this conduct, which might appear to them harsh and cruel, was contrary to his disposition, but according to the rule of treatment observed by General Gage toward the American prisoners in his hands; making no distinction of rank. Circumstances, of which we have no explanation, induced subsequently a revocation of this order; the officers were permitted to remain as before, at large upon parole, experiencing every indulgence and civility consistent with their security.