Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

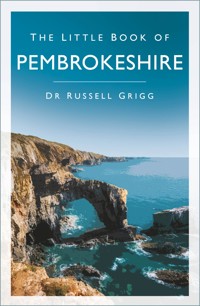

The Little Book of Pembrokeshire is a highly readable guide to the history, culture and landscape of a very special place. Dr Russell Grigg traces Pembrokeshire's enduring appeal, including its rich maritime heritage and diverse culture, from the folk tales of The Mabinogion to the modern surf and music festivals. The reader is taken on a tour of Pembrokeshire National Park (the UK's only coastal park) and its remarkable topography, from enchanting islands such as Caldey and Skomer to the ancient Preseli hills that put the 'stone' in Stonehenge. Also explored is the darker side to Pembrokeshire's tapestry, including castle kidnappings, smuggling, piracy and food riots. Meticulously researched, The Little Book of Pembrokeshire is a sensory delight for both natives and visitors.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 332

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Dr Russell Grigg, 2023

The right of Dr Russell Grigg to be identified as theAuthor of this work has been asserted in accordancewith the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9391 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

List of Figures

Introduction

1

Beginnings

2

The Iron Age Celts, c.600 BC–AD 48

3

Roman Pembrokeshire, AD 48–410

4

Early Medieval Pembrokeshire, AD 410–854

5

The Vikings in Pembrokeshire

6

The Normans and Flemings

7

Tudor Pembrokeshire, 1485–1603

8

The Civil Wars, 1642–51

9

Eighteenth-Century Pembrokeshire

10

Victorian and Edwardian Pembrokeshire

11

The First World War

12

The Interwar Years

13

The Second World War

14

Pembrokeshire After 1945

15

Pembrokeshire Arts

16

Ports and Lighthouses

17

Shipwrecks

18

Beaches

19

Pembrokeshire Towns

20

Pembrokeshire Villages

21

Pembrokeshire Islands

22

Famous Pembrokeshire People

23

Folktales and Customs

24

Pembrokeshire Pubs and Inns

Useful Websites

Select Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Pembrokeshire has produced many fine historians since the sixteenth-century days of George Owen. Although this is a little book, it is indebted to their scholarship. For brevity, I have not included full references and sources, but have highlighted main contributions in the text and select bibliography. I am grateful to Tim Burton and Dr Sioned Hughes, friends and former colleagues, both of whom took time to read through the manuscript and offer helpful suggestions, drawing on their considerable local knowledge. I would like to thank Cadw for providing Figures 4 and 5. Thanks also to Juanita Hall and the team at The History Press for their support through the production process. And finally, thanks to Helen for her continued support and companionship during forays into Pembrokeshire, my home county.

LIST OF FIGURES

1

Pembrokeshire map, 1805.

2

Pembrokeshire – did you know?

3

‘A Farming Settlement c.4000 BC’ by Giovanni Caselli (1979), based on excavations at Clegyr Boia, St Davids, Pembrokeshire, in 1902 and 1943.

4 & 5

A modern interpretation of how stones may have been moved to create Pentre Ifan.

6

Haverfordwest Priory.

7

St Govan’s Chapel.

8

A portrait of William the Conqueror from the Bayeux Tapestry.

9

Round chimneys, wrongly attributed to the Flemings.

10

Pembroke Castle.

11

Picton Castle.

12

An eighteenth-century print of Henry VII.

13

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, as depicted in 1911.

14

The burning of William Nichol.

15

A bit of ‘Old Tenby’, featuring the Tudor Merchant’s House.

16

A Welsh Beggar.

17

A South Wales Railway timetable.

18

Pembrokeshire miners.

19

The death of Queen Victoria announced by the Telegraph.

20

1890s Pembrokeshire bicycle advertisements, many of which targeted women.

21

Passengers rescued from the Falbala.

22

A map showing the location of the Loch Shiel wreck.

23

A nineteenth-century print of a lifeboat crew.

24

Milford Haven, c.1837.

25

St Davids Cathedral.

26

Tenby, c.1837.

27

Bathing dresses.

28

Seafaring pilgrims.

29

A nineteenth-century painting of Sir Rhys ap Thomas, showing Carew Castle in the background.

30

Llangwm fisherwomen.

31

Manorbier Castle.

32

Caldey Abbey, 1907.

33

St Catherine’s Island, Tenby, 1853.

34

Robert Recorde.

35

Barti Ddu.

Fig. 1 Pembrokeshire, 1805. (Piccadilly, A Map of South Wales, 1805)

INTRODUCTION

Pembrokeshire is a land of contrasts, which I know from personal experience. Although I was born and raised in the seaside resort of Tenby, I spent many weekends in my grandparents’ cottage at Pontnewydd, on the banks of the River Nevern in north Pembrokeshire. Its charming, chocolate-box façade belied the absence of modern amenities. For example, the single toilet was at the end of the garden by the river, the bedrooms lacked central heating, and we often had to rely on candlelight due to power outages. Looking back, it’s difficult to believe this was the 1960s and not the 1860s.

My maternal grandfather was a Welsh speaker, who learnt English by talking with summer visitors who stayed in the caravan park at Llwyngwair Manor, where my great grandfather worked as the lodge keeper. On my Tenby-based paternal side, no one spoke Welsh.

The binary nature of my own Pembrokeshire childhood is indicative of the county’s deeper contrasts. For more than 900 years, the Welsh-speaking north and the anglicised south have been separated by an invisible frontier or boundary known as the Landsker; literally meaning a ‘cut into the landscape’. Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, the Normans built a series of castles to keep the Welsh at bay. These stretch from Laugharne, on the Carmarthenshire coast, through Narberth, Wiston and Roch, approaching St Bride’s Bay to the west. Place names are an indicator of this division, with the likes of Johnston and Honeyborough to the south and Eglwyswrw and Mynachlog-ddu to the north. The latter are within the district most strongly associated with the Welsh language (Y Fro Gymraeg), extending westwards from Anglesey through Ceredigion, Carmarthenshire and north Pembrokeshire. Modern DNA evidence confirms that the genetic make-up of those living in the north of the county differs from ‘the down belows’, who occupy what has been called for centuries ‘Little England beyond Wales’.

The linguistic divide has been a sharp one. For example, in 1921, 97 per cent of those living in the parish of Llandeloy spoke Welsh, whereas less than 10 km away, in the parish of Nolton, the figure was only 3 per cent. However, the division has become less clear cut, with growing interest in Welsh language education in the south alongside migration and Anglicisation in the north. Moreover, the very notion of the Landsker for some has become outdated, with its emphasis on differences and the implication that those below the Landsker are ‘less Welsh’ than those to the north.

For thousands of first-language Welsh speakers like my grandfather, speaking Welsh is integral to their identity and everyday life, just as speaking French is in France. For the language to thrive, it needs local and national support. This has increased significantly since 1997, when Wales received devolved powers in areas such as education, which has added political impetus for Welsh-medium schooling in Anglicised towns such as Tenby, Haverfordwest and Pembroke. More than 40 per cent of educational provision in the county has some form of Welsh-medium teaching.

Language is an important but not defining characteristic of identity. Around 70 per cent of Pembrokeshire’s population do not speak Welsh, according to the Welsh Government’s population survey in 2021.

The question of identity is not simply an academic discussion. In 2022, when a frozen food company in Pembroke Dock advertised its ice cream as ‘Made for you in Little England beyond Wales’, it upset a lot of local people. The company duly apologised and changed its branding.

While there are differences among the communities of Pembrokeshire, perhaps they have more in common than sets them apart. For example, Pembrokeshire is united by its strong maritime tradition. There is also a shared sense of pride in the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, designated in 1952, which embraces just over a third of the county. It is rightly considered by the Welsh Government as a major health and well-being resource, offering active benefits associated with the likes of surfing, sailing, diving, climbing, swimming, kayaking, coasteering, geocaching (a form of hide-and-seek), horse riding, caving, walking and cycling, and the passive joy of taking time out to absorb the likes of the ancient Pengelli Wood (near Eglwyswrw), which is at least 10,000 years old, or observing close up the puffins and other wildlife on Skomer Island.

The Pembrokeshire landscape is an evocative one that transcends the immediate senses. This experience was captured 1,000 years ago in The Mabinogi, the eleventh-century Welsh folktales which described Pembrokeshire as a land of mystery and enchantment (Gwlad hud a lledrith). The ancient hills and coast radiate magic in various forms, from myths and legends to the distinctive, reflective light, which have inspired generations of poets, writers, artists, musicians, mystics and others.

It continues to do so. Pembrokeshire beaches have featured in films such as Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2009), Ridley Scott’s Robin Hood (2010) and Snow White and the Huntsman (2012). As the recent pandemic restrictions eased, one journalist visiting from London commented that Pembrokeshire was ‘untamed, underrated and ripe for adventure’.

In fact, Pembrokeshire has long been valued as a special place. Perhaps it is because of its size – little more than 30 miles as the crow flies, north to south or east to west (Figure 2). ‘There is no spot where the peasantry exhibit more happiness than in the northern parts of Pembrokeshire,’ wrote one travel writer in 1799, while a modern guidebook confidently proclaims, ‘Pembrokeshire possesses everything’.

Many residents have gone so far as to suggest that this is ‘God’s own country’. The fact that this has also been said of places as far apart as New Zealand, India and Zimbabwe, or closer to home, Yorkshire, does not seem to matter. Pembrokeshire is held up as offering something for everyone – from ramblers, nature lovers and surfers, to musicians, artists, filmmakers and poets, from those looking for a barmy summer stag or hen party in Tenby to those seeking monastic solitude on Caldey Island or spiritual renewal in St Davids Cathedral.

As this book aims to highlight, Pembrokeshire has much to offer in its rich heritage, culture and breathtaking coastline, widely regarded as the best in the world. It also has a fascinating history and I have tried to bring this to life with human stories about work, poverty, health, travel, war, education, entertainment and other themes that have affected people’s lives in Pembrokeshire.

Fig. 2 Pembrokeshire – Did You Know?

1

BEGINNINGS

When does Pembrokeshire (Sir Benfro) begin? The name itself means ‘headland’ and is a combination of the old Brythonic or Welsh words, Pen (head) and Bro (region or district). Originally, Penfro was one of the land divisions or cantrefs which made up the old medieval kingdom of Dyfed. The shire element in Pembrokeshire comes from the Anglo-Saxon ‘scir’, a model of local government based on the ‘shire-reeves’, or sheriffs, who were responsible for keeping order and collecting taxes on behalf of the king.

With the arrival of the Normans, Pembroke was made a county palatine in 1138, which meant that the Earl of Pembroke was granted special authority on behalf of the king. But it was not until the reforms of Henry VIII that the territory of modern Pembrokeshire began to take shape. Through the Acts of Union (1536 and 1542–43), Wales was divided into thirteen Welsh counties or shires, where the same English laws were to apply. In 1974, these were reorganised into eight new counties, one of which was Dyfed, comprising Pembrokeshire, Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire. While the name Dyfed remains in use for certain purposes, such as policing (Dyfed-Powys Police), as a term for council administration it proved unpopular. Hence, in 1996 the old counties of Pembrokeshire, Cardiganshire (which became Ceredigion) and Carmarthenshire were reinstated.

Natural history affords another perspective on how the area has developed. As the writer Vyvyan Rees put it, ‘Stones, the sea and the weather have moulded the look of Pembrokeshire. Man has merely scratched the service.’

In terms of geology, Pembrokeshire began in the age of volcanic activity when Precambrian rocks formed St Davids Peninsula, around 650 million years ago. Over a very long period of time, a series of severe climate changes with variations between glacial (cold) and interglacial (warm) years created different landscapes, climates, fauna and environments. The legacy can be seen in northern Pembrokeshire, where valleys were carved out and the rugged hills of igneous rock and slate were splintered by the Irish Sea glaciations.

At one time the sea level around the Welsh coastline was estimated to be at least 50m below the present level because so much water was locked up in ice. During the last glaciation, about 18,500 years ago, ice probably enclosed the whole of Pembrokeshire. The Irish Sea Ice Sheet covered St Davids Peninsula, reaching the Preseli Hills to the north and as far south as the entrance to Milford Haven. As the climate warmed up, sea levels rose and the islands of Ramsey, Skomer and Skokholm were eventually cut off from the mainland.

Pembrokeshire has been left with a range of impressive geological features, including:

• The Three Chimneys on Marloes Sands – near-vertical sandstones that stand out in the cliff

• Red Berry Bay on Caldey Island, named after the red sandstone cliffs

• Den’s Door, north of Broadhaven, one of two sea arches

• the Ladies’ Cave anticline at Saundersfoot – a remarkable chevron fold

• the Green Bridge of Wales, Castlemartin – covered in vegetation and formed in the age of the dinosaurs

• Pen-y-holt Stack, Castlemartin – a limestone sea stack

• Huntsman’s Leap, south of Bosherston – a deep limestone chasm

• columnar ballast at Pen Anglas headland, showing pillow-shaped lavas.

Around 40 per cent of the Pembrokeshire coastline comprises geological features that are protected as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). This means that they represent the best of our natural heritage, whether rocks, landform, flora or fauna. The coastline itself is regarded as one of the most stunning in the UK, if not the world. Its extraordinary range of rock colours and textures has left many sightseers in awe. As the writer Brian John explains, ‘One minute you are walking along the top of a high vertical cliff, and one minute later you are on the lee side of a headland where a low sloping cliff is covered by luxuriant vegetation.’

The moist, warm oceanic climate, along with the variations in rock and soil, support a wide range of habitats for plants and wildlife. The grasslands and heath on the more exposed coastal slopes and clifftops contrast with sand dunes in broad bays, freshwater marshes and fens in coastal river valleys. Pembrokeshire’s mild climate and its fertile soil offer a long growing season, notably for early potatoes. In 2013, the European Commission awarded Pembrokeshire Earlies Protected Geographical Indication status (PGI), meaning they have the same protection as Champagne and Parma ham.

* * *

While geology tells us how Pembrokeshire was formed over millennia, when does the human story in this region begin?

Archaeologists estimate that the earliest bones in Wales date to around 225,000 BC and were discovered in Pontnewydd Cave (Denbighshire). These were the remains of Neanderthals, considered an archaic species of humans, named after their discovery in Germany’s Neander Valley. The bones of bear, horse, deer and hyena along with flint tools have been found at Hoyle’s Mouth (Penally), dated to around 30,000 years ago.

Until the nineteenth century, it was commonly thought that human origins could be traced back to no more than 6,000 years ago, but the emergence of archaeology as a science showed that humans have a much older existence. When in 1851 stone axes were discovered in Devon alongside the remains of cave bears, woolly rhinoceros and other extinct species (all under a sealed rock), a new term was invented to describe the vast age before writing was invented: ‘prehistoric’.

PREHISTORY

If the time when humans are known to have lived in Britain is visualised as a 100 squares, 99.9 of those squares would be occupied by prehistory. The chronology of prehistory is typically split into ages based on how soon the earliest peoples mastered various technologies. The Stone Age, the first of these ages, is so vast that archaeologists further subdivide this into three phases so that they can more accurately describe changes over time.

The Old Stone Age, or Palaeolithic (c.225,000–8000 BC)

The most significant development in the Old Stone Age was the mastery of fire, which is seen as a mark of human intelligence which separated us from animals. Fire provided warmth and lighting, protection from predators, a means for cooking, forging spears, axes, beads and bows, and a social focus, which indirectly helped develop language.

Fire was essential in surviving the freezer of ice-age winters. During the most recent glaciation (about 18,500 years ago), the northern part of Pembrokeshire remained covered in ice, but the south was exposed and experienced tundra conditions. The melting of the ice drowned river valleys, creating the likes of the Milford Haven waterway. The dramatic shingle ridge at Newgale beach is a legacy of the last glaciation and is the longest beach in the county (2.5km or 2 miles, end to end). The ice also carried boulders (known as erratics, after the Latin word ‘errare’, meaning to wander) hundreds of kilometres from their original location. One interesting aside is that two of these boulders formed the headstones for the burials of Colonel Francis Lambton and his wife, Lady Victoria, from Castlemartin. They were amateur geologists who, in the early 1900s, restored the medieval Flimston Chapel, which sits in the middle of the Castlemartin Royal Armoured Corps firing range, and has done since 1940.

Marine archaeologists have mapped how prehistoric Pembrokeshire changed, using survey data of the seabed. Towards the end of the Palaeolithic period, around 10,000 years ago, Britain was still joined by a ‘land bridge’ to mainland Europe, while Cardigan Bay, Liverpool Bay, the Severn Estuary and the Bristol Channel simply did not exist.

The Middle Stone Age, or Mesolithic (c.8000–4500 BC)

For archaeologists, Nab Head in Pembrokeshire is the most significant Mesolithic site. Climate changes meant that the original site would have been around 6km inland from its present coastal edge. It has been likened to a kind of production factory for making tools and processing food. Incredibly, more than 40,000 stone tools and 700 stone discs or beads have been discovered here over the course of a series of excavations conducted since the nineteenth century. The beads are a couple of millimetres thick and with a single hole drilled from one side, resembling polo mints. They were probably used as a medium of trade.

Another remarkable Mesolithic discovery was made in 2010 when a Lydstep resident contacted Dyfed Archaeological Trust to report unusual footprints on the beach. They had been solidified in a peat deposit that was once the floor of a shallow lagoon in the late Mesolithic period. The deep impression suggests that a group of adults and children were standing still, waiting for some time in one place. Archaeologists speculate that this was a hunting party, hidden in the reeds, ready to pounce on any unsuspecting animal about to take a drink.

The footprints were close, and possibly linked, to an earlier discovery known as the Lydstep Pig. In 1917, local antiquarian Arthur Leach found a wild boar skeleton trapped beneath a tree trunk with two broken flint points in its neck. The Lydstep Pig is estimated to be 6,300 years old. While the hunters may have caught their prey for food, it is also possible that the pig was a votive offering at the water’s edge, pinned down by a tree trunk. Water, with its cleansing and life-giving qualities, has long been associated with rituals. It is remarkable how a child of our time can walk along the beach and place her feet in the prints of a young Mesolithic hunter – one small step in a connection spanning thousands of years.

Another important discovery followed the winter storms of 2013–14. Remnants of Mesolithic trees and human footprints along Newgale beach were exposed as high seas swept aside a bank of pebbles which had covered them. This woodland area may have been the site of hunters and gatherers searching for game and edible plants, nuts and berries 10,000 years ago. Following the storm, a Newgale resident found the horns of an auroch, an ancestor of our domestic cattle, which became extinct in the seventeenth century. Perhaps this was the prey of the prehistoric hunting party.

As yet, no Mesolithic houses have been found in Pembrokeshire, unlike in other parts of the UK, such as Star Carr in Yorkshire. The traditional view is that hunter-gatherers did not have fixed settlements but moved around, depending upon the seasonal search for food. They gathered wild plants, hunted animals, birds and fish, and used animal skins to make clothes. They may have lived in caves or used temporary shelters as they travelled.

The remains of Mesolithic reindeer and woolly mammoth bones have been discovered in Wogan Cavern under Pembroke Castle. In 2021, while the wardens on Skokholm Island were in lockdown due to the coronavirus, they discovered a ‘bevelled pebble’ in a rabbit’s hole. Archaeologists later confirmed that this was a prehistoric tool, probably used by hunter-gatherers to shape seal hides for use as skin-covered vessels or for processing shellfish.

The New Stone Age, or Neolithic (c.4500–2500 BC)

The New Stone Age is marked by a gradual decline in hunter-gathering, with the introduction of domesticated animals, the clearance of woodland, the beginnings of arable farming and the emergence of settlements. In 2021, archaeologists found dairy fat residue, probably from yoghurt, in shards of decorated pottery at Trellyffaint, near Newport. This suggests that dairy farming in Pembrokeshire has been practised for at least 5,000 years, the earliest proof of dairy farming in Wales. The remains of timber and daub huts with stone footings at Clegyr Boia near St Davids (Figure 3) and Rhos y Clegyrn, point to the existence of small farming groups growing wheat and barley and keeping cattle, pigs and sheep.

Technological developments included the use of polished stone axes. These were made by chipping a flint block into a rudimentary shape before grinding and polishing it with sand and water. Experiments show that these polished axes can be as effective as modern steel ones when applied to birch and other softwood. The Preseli Hills provided the raw material to make these axes.

Fig. 3 Farming settlement around 4000 BC by Giovanni Caselli, 1979. Based on excavations at Clegyr Boia, St Davids, Pembrokeshire, in 1902 and 1943. (©Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales)

Communities started to build megalithic structures, which served several purposes. Primarily, they were sites for communal burials, often over many generations. It is possible that these were focal points for social gatherings.

Pembrokeshire has around eighty known burial places. The most impressive and iconic of the monuments is Pentre Ifan (at Nevern), which is older than the Egyptian pyramids. The raised stone weighs 16 tons and the structure dates to around 6,000 years ago. When Victorian tourists visited in 1859, five persons on horseback were reportedly capable of standing beneath the capstone at the same time. The Victorians thought that it served as a resting place for a local chieftain and his family. They also concluded that the builders moved the stones into place from the ridge nearby using some ‘rude mechanical appliances’. The initial act of moving and raising such large stones likely involved a combination of brute force and wooden rollers and ropes (Figures 4 and 5).

Pentre Ifan is one of many ancient monuments and burial sites to be found within the Newport–Nevern district. Some of these are on private property and can only be accessed by foot. Carreg Coetan Arthur, on the banks of the River Nevern, is one of the best preserved. King Arthur is supposed to have played a game of quoits (‘coetan’) with the stone of the tomb, where cremated human remains and stone tools have been found. The Carreg Samson dolmen (at Abercastle), which overlooks Cardigan Bay, has a capstone which weighs around 25 tons resting on three uprights. It has been estimated that to erect the whole structure would have taken up to 15,000 worker-hours. But the biggest capstone in Britain is to be found at Garne Turne (near Wolfscastle), which is estimated to weigh 80 tons, the equivalent of 100 cows.

Of Pembrokeshire’s ancient stone circles, the most striking is at Gors Fawr (near Mynachlog-ddu), about 22m across, comprising an almost perfect ring of sixteen pillars or boulders. Two other notable monuments are Bedd Arthur (technically an oval setting rather than a circle), comprising seventeen bluestones at the east end of the Preseli ridge, and Carn Menyn Cairn (near Mynachlogddu). In total, around seventy or so standing stones exist, serving as uprights of burial chambers or forming free-standing monuments, as funeral memorials, objects of worship, boundary markers or commemorations of events, such as battles.

Figs 4 & 5 Modern interpretation of how stones may have been moved to create Pentre Ifan. (Cadw, illustration by Jane Durrant, © Crown, 2022)

THE BLUESTONE MYSTERYOF STONEHENGE

Archaeologists have long debated how stones weighing up to 4 tons from the Preseli Hills in Pembrokeshire found their way to Stonehenge, in Wiltshire, a distance of 150 miles (250km). One theory is that they were moved on sledges and rollers to Milford Haven, from there on rafts across the Bristol Channel, up the River Avon and then again on sledges and rollers to their final destination. Perhaps horsepower was involved at some stage. Another theory is that the monoliths were moved much earlier in time, perhaps half a million years ago, by shifting glaciers.

Recent analysis of charcoal and sedimentary remains at Waun Mawn in the Preseli Hills suggests that an original circle of bluestones may have been dismantled and relocated to Stonehenge as the Preseli people migrated, perhaps as a reminder of their ancestral identity. Archaeologists estimate that Waun Mawn once had a circle of between thirty and fifty stones, but only four remain there.

The archaeologist Francis Pryor reminds us that we should not think of Stonehenge in modern terms, as some form of civic engineering project governed by efficiency and effectiveness. Rather, he speculates that the actual transportation and erection of the stones formed part of a ceremonial ritual, a joyous event with feasting, singing and socialising in the evenings. Perhaps the act of moving the bluestones was a symbolic means of unifying two different ancestries from different parts of Britain.

An examination of the stones has shown that they even have musical qualities. When tapped with a small ‘hammer’, the stones emit a ringing quality.

There are also suggestions that the stones had religious significance or medicinal qualities when seen in relation to water. The original Stonehenge site had an Avenue which connected the stones to the River Avon. One view is that the Pembrokeshire bluestones formed a temple and were seen to possess curative powers, offering comfort and protection to pilgrims and travellers drawn to the area.

We do not know exactly how and why the bluestones came to be at Stonehenge, but this is among Pembrokeshire’s best-known contribution to British heritage.

The Bronze Age (c.2500–600 BC)

The landscape of Pembrokeshire and the rest of Wales was transformed by the discovery of metals, which led to the development of the plough and the wheel. The earliest metalworkers in Britain used copper, gold and bronze to forge axes, daggers and other weapons, as well as ornaments. In Wales, the earliest records of metal tools date to about 4,000 years ago. The most significant findings in Pembrokeshire include a hoard of spearheads from a peat bog in Freshwater West in 1991 and various objects found at Marloes in 2013, including fragments of two sword blades, a scabbard fitting, a knife and six pieces of copper ingot. Although gold was mined at Dolaucothi (Carmarthenshire) from at least 5,000 years ago, the only item of gold found in Pembrokeshire to date is a crumpled gold ‘lock-ring’ from Newport, now held by the National Museum of Wales and viewable online.1

During the Bronze Age the importance of megaliths declined, with tombs being blocked and abandoned. Round barrows and cairns started to appear, and new styles of Beaker pottery and the working of flint were increasingly adopted. It is estimated that Pembrokeshire has around 160 round barrows of up to 4,000 in the whole of Wales. They vary in shape and size, reflecting the status of the individuals buried. The largest and most famous are the three stone cairns on the summit of Foel Drygarn, each around 25m in diameter and standing 3m high. This may have covered the bones or ashes of high-ranking individuals. These burial cairns were never plundered for their stone, despite being surrounded by hundreds of shelters within the settlement, which suggests that there was a high degree of reverence for dead ancestors.

The presence of stray finds and scattered monuments shows that people were active right across Pembrokeshire in the late Bronze Age. In 2006, archaeologists revealed numerous Bronze Age cremations at Steynton (Milford Haven) while the new South Wales Gas Pipeline was being laid. More than twenty adults and children were buried at the site, along with food vessels and urns for the next life. Archaeologists have also found evidence of pits, hearths, troughs and burnt stone, the remnants of a cooking place where water was once heated.

The standing stone at Devil’s Quoit, Stackpole Warren, is 1.7m tall and likely formed part of a timber structure that burnt down around 3,400 years ago. It is perhaps a site of ritual and domestic significance, being the earliest date for such a Bronze Age structure. Archaeologists who excavated the surrounding field system found nearly 800 flints, along with evidence of roundhouses, cooking pits, hearths, charred cereal grains and pottery sherds, suggesting the area was inhabited over many centuries, spanning the Neolithic to Roman periods.

It was once thought that waves of immigrants from central Europe arrived in Britain, bringing a new ‘Celtic’ culture and language by about 600 BC. Archaeologists now emphasise continuity rather than sudden change and the merging of cultures through trade, marriage, feasting and festivals. Rather than acting as barriers, the western seaways were important channels of communication and exchange between Pembrokeshire, north-west Wales, south-west England and Brittany. The presence of hilltop enclosures, the appearance of iron and the development of tools and weaponry were signs of new ways of life that would come to characterise the next phase of human settlement.

1 https://museum.wales/collections/bronze-age-gold-from-wales/object/eb9e3f9c-cce7-39de-a8f3-7df923819924/Late-Bronze-Age-gold-lock-ring/content/

2

THE IRON AGE CELTS, C.600 BC–AD 48

The oldest surviving written references to what is now Wales and Pembrokeshire appeared in the second century AD when the Greek cartographer Claudius Ptolemy mentioned the Demetae, the Celtic tribe, whom the Romans say occupied south-west Wales. We know hardly anything about these people, although more generally the Classical writers regarded the ‘Keltoi’ or ‘Celtae’ as ignorant, uncivilised ‘barbarians’ who babbled, making unintelligible sounds (‘bar bar bar’). Unfortunately, we do not know what the Celts thought because they left no written records. Their culture emphasised storytelling, metal and craftwork rather than reading and writing.

The Celts may have lived up to their reputation for being ‘madly fond of war, high-spirited and quick to battle’. But they were also highly skilled craftsmen, evidenced by surviving brooches, cauldrons, decorative pins, shields and swords, which are exhibited in the National Museum of Wales, the British Museum and museums across Europe. Goldsmiths produced stunning torcs, or necklaces, which provided the wearer with divine protection and a sense of mystery, wealth and status.

The Celts were also excellent horsemen and charioteers, masters of wheeled vehicles. In 2018, a local metal detectorist found an Iron Age chariot burial in an undisclosed field in south Pembrokeshire, the first of its kind in Wales. It not only transformed his life, with reports of him receiving a six-figure treasure payment, but it also enhanced our understanding of how such technology and burial practices spread – all of the other British chariot burials found thus far have been unearthed in northern England, notably Yorkshire. The likelihood is that the chariot was owned by a local tribal chief.

The Celts are famous for their hillforts, which offered protection for farms and a place to store food, while also acting as a centre for social activities. There is evidence for around 600 hillforts in Wales, more than 100 of which are found in Pembrokeshire. Most of these were probably small in scale, supporting a family or two. Carn Alw, on the western side of the Preseli Hills, served as a small, enclosed space, possibly a summer grazing retreat or refuge. In contrast, Foel Drygarn (‘hill of three cairns’), on the top of the Preseli Hills, covered several hectares and was likely a tribal headquarters accommodating a couple of hundred people.

The large stone hillfort on Carn Ingli, with its array of ramparts, enclosures and huts, was first mentioned in the twelfth century as the site where St Brynach reputedly communed with angels. But far more common than this were smaller hillforts defended by banks and ditches and limited to less than 1 hectare. Promontory forts jutted out and incorporated steep cliffs as part of their natural defences. Around 100 or so of these have been identified, such as Dale Fort and Porth y Rhaw.

Hillforts were built for shelter and protection. Among the various defensive features of the larger hillforts was the cheval de frise, consisting of upright stones placed in a band outside the main defences with the aim of halting or slowing down the enemy’s advancing chariots. Excavations at the partially reconstructed Iron Age settlement at Castell Henllys (‘Old Palace’), near Eglwyswrw, show that its cheval de frise was preserved under a later defensive bank, suggesting that it was only meant as a temporary measure to be covered over once more substantial resources were available for defence. Several thousand slingstones have been found at Castell Henllys. These were an effective weapon in ancient times, highlighted in the biblical story of David slaying Goliath. An experienced slinger could kill or inflict a serious injury at a distance of 60m or more.

Castell Henllys provides modern-day visitors with a sense of what life might have been like 2,000 years ago, living among the Demetae. Unusually for a promontory fort, the high ground is at the bottom of the site, while the surrounding defences are hidden in trees. The site is approached through leafy woodland and ascends to an open area of just over an acre. This is small in comparison to other Iron Age settlements. Maiden Castle (Dorset), for example, covers 47 acres.

Castell Henllys contains four roundhouses and a granary, which have been carefully reconstructed on the original Iron Age foundation postholes. Two of the four roundhouses have in recent years been dismantled, re-excavated and reconstructed. One of the roundhouse roofs has been rethatched twice.

Archaeologists have been working on the site for nearly forty years. They calculate that the construction of the largest roundhouse alone required thirty coppiced oak trees, ninety coppiced hazel bushes, 2,000 bundles of water reeds and 2 miles of hemp rope and twine, necessary for forming its rafters, posts, ring-beams and wattle walls.

The process of gathering, assembling and maintaining these materials required huge amounts of effort, teamwork and determination. Archaeologists estimate that approximately 100 people lived and worked in a self-supporting community, producing their own food, clothes, equipment, tools and weapons. The site was occupied from the fifth to the second or first century BC.

For some unknown reason, Castell Henllys was abandoned in the late Iron Age. The site may have been occupied in later centuries by Irish settlers, but it fell into obscurity and became overgrown until it was surveyed on a late-eighteenth-century estate map. In 1992, the site was bought by the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, which has since supported an extensive education programme and long-term experimental archaeology project.

In 2001, a group of seventeen volunteers (including three children) agreed to participate in a reality TV show, Surviving the Iron Age, in which cameras followed their attempts to live together at Castell Henllys for seven weeks. While the BBC dubbed the series ‘an experiment in living history’, one of the participants described the experience as ‘hell on earth’. Unfortunately, the filming took place during one of the wettest autumns since records began. The incessant rain made life very uncomfortable in the absence of a change of clothing and modern-day essentials such as toilet paper, deodorant and soap. Two of the children, aged 4 and 5, were withdrawn from the experiment by their mother after the youngest fell ill with food poisoning. Another participant withdrew after catching a bug.

Such experimental archaeology illustrates how surviving the Iron Age was no walk in the park. What became clear to the participants was that survival depended upon meeting the basic needs of shelter, food and water, but in ways that required a lot of collaboration, resilience and hard work. We take for granted turning a tap on to fill a kettle and fetching water from a nearby stream proved too much for the time travellers, who were frustrated by leaking buckets. This happened even though the producers provided a modern-day water tap. The daily grind of menial tasks took its toll within the group and friction soon developed. The humble wellington boot became a prized possession which they could not give up: it was a symbol of how far the twenty-first century had intervened in this living history project.

Water supply was a key factor in the location of hillforts. It is estimated that on the basis of the average person needing 2 litres of water a day to keep going, a hillfort of 100 people would require 44 gallons simply for drinking, let alone cooking. If animals were accommodated on site, then the water demands could be much higher. For these reasons, most hillforts were located near rivers or streams, although water may also have been obtained by catching rainwater, or from springs or wells.

Clegyr Boia hillfort (near St Davids), has two wells nearby: Ffynnon Dunawd and Ffynnon Llygaid. According to myth, the former is allegedly named after a young girl, Dunawd, who had her throat slit by her stepmother. The fountain sprang from where the blood was spilled. Ffynnon Llygaid, on the south side of Clegyr Boia, was reputed to clear eye problems.

For the Celts, the central hearth or fireplace was the basis for cooking food, boiling water, heating the roundhouse and the focal point around which they talked – interestingly, the Latin word ‘focus’ means fireplace. The Welsh word ‘aelwyd