8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Verve Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

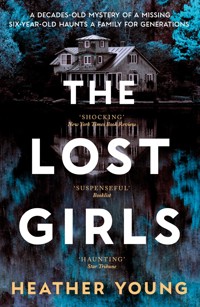

A stunning novel that examines the price of loyalty, the burden of regret, the meaning of salvation, and the sacrifices we make for those we love, told in the voices of two unforgettable women linked by a decades-old family mystery at a picturesque lake house.

In 1935, six-year-old Emily Evans vanishes from her family's summer house on a remote Minnesota lake. Her disappearance destroys the family - her father takes his own life, and her mother and two older sisters spend the rest of their lives at the lake house, keeping a decades-long vigil for the lost child.

Sixty years later, Lucy, the quiet and watchful middle sister, lives in the lake house alone. Before her death, she writes the story of that devastating summer in a notebook that she leaves, along with the house, to the only person who might care: her grandniece, Justine. For Justine, the lake house offers freedom and stability - a way to escape her manipulative boyfriend and give her daughters the home she never had. But the long Minnesota winter is just beginning. The house is cold and dilapidated. The dark, silent lake is isolated and eerie. Her only neighbor is a strange old man who seems to know more about the summer of 1935 than he's telling.

Soon Justine's troubled oldest daughter becomes obsessed with Emily's disappearance, her absent mother reappears, and the man she left launches a dangerous plan to get her back. In a house haunted by the sorrows of the women who came before her, Justine must overcome their tragic legacy if she hopes to save herself and her children.

'The delicacy of [Young's] writing elevates the drama and gives her two central characters depth and backbone… For all the beauty of Young's writing, her novel is a dark one... and the murder mystery that drives it is as shocking as anything you're likely to read for a good long while' - New York Times Book Review

'An addictive, magnificently drawn tale of secrets, lies and tangled relationships, The Lost Girls is one of the most emotionally addictive books I've read in a long time, from the first page to its shocking finale. I read it in one greedy sitting' - Lisa Hall, bestselling author of The Party

'A story that is both eerie and incredibly sad... The Lost Girls is a poignant and engrossing thriller [and] a hugely impressive debut' - Carolyn Kirby, author of Times Historical Novel of the Year When We Fall

'The Lost Girls is a powerful and bruising drama that astutely explores the reverberations of a shocking event through the inextricable layers of family. The story unwinds with a slow but insidious unease, building relentlessly to its shattering and heart-breaking conclusion' - Philippa East, author of CWA Dagger-shortlisted Little White Lies

'A novel of quiet intensity that builds to a terrifying climax. The Lost Girls contains echoes of Kate Atkinson's Case Histories and is just as haunting' - Minneapolis Star Tribune

'Suspenseful and finely wrought, Young's tale is not easily forgotten' - Booklist

'This book has it all — intrigue, complicated relationships, and a thrilling plotline — and it will appeal to fans of longspanning '90s stories like Fried Green Tomatoes and Steel Magnolias' - Bustle

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 581

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Praise for The Lost Girls

‘The delicacy of [Young’s] writing elevates the drama and gives her two central characters depth and backbone… For all the beauty of Young’s writing, her novel is a dark one… and the murder mystery that drives it is as shocking as anything you’re likely to read for a good long while’ – New York Times Book Review

‘Suspenseful and finely wrought, Young’s tale is not easily forgotten’ – Booklist

‘This book has it all – intrigue, complicated relationships, and a thrilling plotline – and it will appeal to fans of long-spanning ’90s stories like Fried Green Tomatoes and Steel Magnolias’ – Bustle

‘I was swept into The Lost Girls on the very first page… Heather Young weaves a captivating, multi-layered story that you won’t want to put down’ – Vanessa Diffenbaugh, internationally bestselling author of The Language of Flowers

‘Riveting… Told with finesse and an unflinching eye, The Lost Girls examines the bond between sisters, what it means to keep a promise, and how one family’s secrets can stretch across generations’ – Tara Conklin, New York Times bestselling author of The House Girl

‘A novel of quiet intensity that builds to a terrifying climax. The Lost Girls contains echoes of Kate Atkinson’s Case Histories and is just as haunting’ – Minneapolis Star Tribune

‘Heather Young has crafted a gorgeous book that moves artfully back and forth through time, weaving a suspenseful tale steeped in generations of family secrets’ – Jennifer McMahon, New York Times bestselling author of The Night Sister

‘Vivid and suspenseful’ – Seattle Times

‘Heather Young is a master weaver of plot, time, and character. Her prose is confident, her story ambitious. The result – The Lost Girls – is a haunting and dynamic debut that never falters’ – Ivy Pochoda, author of Visitation Street

‘Heather Young’s clear, unsentimental writing is bracingly observant, psychologically astute, and suspenseful. Her characters include people who cannot love, people who destroy what they love – and people who slowly, agonizingly, figure out what love actually is. From its opening… to its troubling, thrilling conclusion, I found this novel irresistible’ – Alice Mattison, author of Conscience

‘Suspenseful… Young juggles each narrative skillfully, noting the terrible ways in which secrets and evasions shape our lives – and how even when it seems unlikely, redemption is always possible’ – Miami Herald

For my father – my inspiration

And my mother – my hero

Sister – if all this is true, what could I do, or undo?

– Sophocles, Antigone

Lucy

I found this notebook in the desk yesterday. I didn’t know I had any of them left, those books I bought at Framer’s with their black-and-white marbled covers and their empty, lined pages waiting to be filled. When I opened it, the binding crackled in my hands and I had to sit down.

The edges of the book’s pages were yellow and curled, but their centers were white, and they shouted in the quiet of the parlor. Long ago, I filled these books with stories, simple things the children enjoyed, but this one demanded something else. It was as though it had lain in wait beneath stacks of old Christmas cards and faded stationery until now, when my life has begun to wane with the millennium and my thoughts have turned more and more to the past.

It’s been sixty-four years. That doesn’t feel so long, strange though it may seem to you, but Mother is dead, and Father, and Lilith; I am the last. When I am gone, it will be as though that summer never happened. I’ve thought about this as I sit in my chair on the porch, as I take my evening walk up to the bridge, and as I lie awake listening to the water shifting in the dark. I’ve even taken to sleeping in Lilith’s and my old room, in the small bed that used to be mine. Last night I watched the moonlight on the ceiling and thought of the many nights I have lain there: as a child, as a young girl, and now as an old woman. I thought about how easy it would be to let all of it pass from the earth.

When morning came, I made my buttered toast and set it on its flowered plate, but I didn’t eat it. Instead I sat at the kitchen table with this book open before me, listening to the wind in the trees and feeling the house breathe. I traced my finger along the scratches and gouges in the elm table my great-grandfather made for his new wife in the century before I was born. It was the heart of the cabin he built on their homestead, and of the home their son built in the town that came after, but their grandson thought it crude, fit only for this, his summer house. Its scars are worn now; the years have smoothed them to dark ripples in the golden wood. As I said, I am the last. Since Lilith’s passing three years ago, the story of that summer has been mine alone, to keep or to share. It’s a power I’ve had just once before, and I find I am far less certain what to do with it now than I was then. I hold secrets that don’t belong to me; secrets that would blacken the names of the defenseless dead. People I once loved. Better to let it be, I told myself.

But this notebook reminds me it’s not so simple as that. I owe other debts. I made other promises. And not all the defenseless dead, loved or not, are virtuous. Still, I have no doubt that I would have remained silent, waiting for my own death to decide the matter, had I not found it. Its empty pages offer me a compromise, one that I, who have rarely had the fortitude to make irrevocable choices, have decided to accept.

I will write my family’s story, here in this book that bided its time so well. I will tell it as fully as I can, even the parts that grieve me. When I am done I will leave it to you, Justine, along with everything else. You will wonder why I’ve chosen you and not your mother, and to that I say that you are the only one to whom the past might matter. If it does, you will come here when I am gone, and Arthur will give this to you, and I will trust you to do with us as you see fit. If it does not – which may well be, for I knew you so briefly, and you were just a child – then you won’t come. You’ll be content to let the lawyers and the realtors do their work, to continue your life without seeing this house or the lake again. If that is the way of it, I will instruct Arthur to burn this book unread. For I believe it will then be all right to let that summer slip away, and Emily with it. Like all the other ghosts of forgotten things.

It was 1935. I was eleven, Lilith thirteen, and Emily six. Our family lived in town then, in the brown house my grandfather built, but we spent our summers here, in our yellow house on the lake. The day after school ended, Mother packed our trunks with our sundresses, swimming suits, and hats, and Father drove us the twenty miles that spanned our known world. Lilith, Emily, and I sat in the back of the Plymouth, I in the middle as usual. When I pressed my foot against Lilith’s, she pressed back.

You knew Lilith for such a short time, that one summer twenty years ago when you and your mother came, and I imagine to you we were just two old women living out their days on a screened-in porch. I wish you could have known her – really known her – because any story of which Lilith was a part became her story, and my story is no different. My earliest memory is of her directing me to place my feet in the footprints she made on the beach, leading me in twirls and spins until I lost my balance and fell. It was only a game, but it was also how we spent our childhood years: I followed her everywhere and did everything she did, though never as quickly or as well.

Then, in the spring of 1935, something changed. We still went everywhere together, but she no longer wanted to go to Seward’s pond or into the tree house Father built in our backyard, and she wouldn’t play hopscotch or swing on the swing. Instead she spent a great deal of time looking in her mirror, brushing the dark curls that fell to her waist. She had an odd sort of face, with a too-long nose and a too-wide mouth that conspired with her delicate cheekbones to make something improbable and arresting. Now she studied it as if it were a machine she was trying to figure out.

She was taller, too, and though she still wore last year’s dresses with the hems let down, her body was changing. In April she pulled me into the bathroom we shared to show me the small buds on her chest. In May, Mother bought her a brassiere. At first she needed my help to hook it in back, its tiny claws slipping into fragile eyes. Afterward, wearing it with her shoulders squared and her chin high like the girls in the Sears & Roebuck catalog, she looked like someone very different from who she’d been.

Of course, there’s a big difference between eleven and thirteen. I know that now. But then, I saw only that I was being left behind on a journey I didn’t understand and didn’t want to make, and as spring deepened toward summer I decided the three months our family would spend here at the lake offered my best chance to pull Lilith back to me. Surely, as we played our games in the woods, sat on the bridge over the creek, and lay in our twin beds whispering in the night, she’d shed this odd veneer of adulthood she’d been trying on. When her foot pressed mine in the car, that hope expanded even as the road narrowed around us.

We arrived in that afternoon hour when the sunlight turns from white to gold and the water is its deepest blue. The house, shut up for winter, was chilly and dark, but as we opened the curtains and raised the window sashes, it breathed in the warm breeze and shook off the gloom of the long cold season. It has always seemed a living thing to me, this house, and I felt its spirits lift as it filled with our voices and the clattering of our shoes across its pine floorboards.

Lilith and I carried our trunk to our airy green bedroom. We loved the annual ritual of hanging our summer dresses in the closet, lining our shoes on the shelves, arranging our hats on the hooks over the dresser. In town we slept in separate rooms, so our unpacking here was more than a simple filling of drawers and closets; it was a ceremonial reclaiming of a shared territory. As we unpacked that day, Lilith was very like her old self, making plans for us to visit the Hundred Tree as we laid sheets on our beds and shook out the quilts that had spent the winter sealed in the hallway linen press. Meanwhile, Mother settled Emily in her small bedroom across the landing, and Father unloaded the rest of the suitcases and trunks, which seemed to get more numerous every year. Outside, up and down the dirt road that fronted the lake, our summer neighbors greeted one another as they, too, opened their houses to the sun.

There are seven houses here, all built between 1905 and 1910. That was when our small-town Minnesota aristocrats, emulating New York’s Vanderbilts and Rockefellers, built summer homes to which they escaped while the lesser citizens sweltered in town. The Joneses, who owned the general store, were the first; then came the Pughs, two generations of whom were the town’s doctors; the Davieses, whose grandfather was the circuit judge; the Lewises, whose father was our dentist; and the Williamses, who wrote our wills and gave the town its name. My own father ran Evans Drugs, which his grandfather had founded. The biggest house belonged to Robert Lloyd, who owned almost everything else and who, like his father and grandfather before him, was the town’s mayor. All of us were descended from the small group of men who fled the coal mines of Wales to found Williamsburg some eighty years before, and we considered our prosperity and social prominence to be our birthright.

Today these houses are in disrepair, but surely you can see how lovely they once were. In the summer of 1935 they were just beginning their decline: paint was fading and would not be freshened; a broken screen here and there would not be replaced. As a child I didn’t know the extent of the hard times, although I saw Mother’s little economies – the let-down hems, the resoled shoes – and resented them. The very next year, the Joneses and the Davieses would not come to the lake at all. Their houses would sit closed until they were sold to families from Minneapolis who came up for a week and rented them out for the rest of the season. Within a few years the other lake families would do the same, until Lilith, Mother, and I were the only ones left.

As I look back, knowing everything that was to come, the first day of my family’s last summer together takes on a melancholy it did not have then. To the contrary, I loved that day as I had loved all the first summer days that came before. It was one of the few times when I felt our family was like all the others, not just in appearance, but in truth. Father’s stern manner softened as he deferred to Mother in the domestic matters of unpacking and moving in, and Mother’s voice had a lilt that I never heard elsewhere. Emily, normally so somber, skipped around like the six-year-old girl I often forgot she was. Best of all, Lilith chattered and laughed as if she were twelve again. I watched all this, the normal happiness of a family on holiday, and I smiled until my cheeks ached.

For supper that first night, the lake families prevailed upon the Millers, the half-Chippewa family who owned the fishing lodge, to cook for us. The hours we spent laying out our bed linens and placing our clothes in freshly papered drawers the Millers spent roasting chickens, boiling corn, and baking bread. No doubt they worked for days to feed all of us, more than sixty people, but times were hard for them, too; I imagine they were glad to have the money we paid.

Abe and Matthew, the Miller sons, brought tables and chairs to where three picnic benches sat on the sandy grass between the road and the narrow beach. There the women, cheeks rosy from the exertion of moving in, clustered in knots and patted wisps of hair into place while the men rattled the ice in their cocktails and speculated on the season’s walleye catch. They wore cardigans and light coats; in June the evenings were cool, though the sun hung high above the hills that crowded the lake’s western shore. When it was time to eat, everyone bowed their heads as Father, the closest thing among us to a minister, said grace in a quiet that was as profound as it was temporary. Then the feast began, the children eating as quickly as their mothers would allow so they could resume running up and down the dock and around the trees. Even Lilith and I, who otherwise kept to ourselves, always joined the games of tag and kick-the-can that heralded the start of summer.

But this year, Lilith sat on a picnic bench with her hands folded in her lap while the other children chose up teams. I sat beside her, digging my toe into the grass, unease shifting the creamed corn and chicken in my belly. I couldn’t bring myself to join the game without her – she was my conduit to the others, her imperious confidence paving a way for me and my small awkwardnesses.

‘Don’t you want to play?’ I asked.

‘We’re not children, Lucy,’ Lilith said.

I wanted to say that all the teenaged boys were playing, even Stuart Davies, who’d just graduated from high school, but I knew she was talking about the teenaged girls, who sat nearby, whispering as they watched the boys run about on the sandy road. So I said nothing and tried to remind myself that tomorrow we were going to the Hundred Tree. She’d promised.

I heard Mayor Lloyd’s voice booming from a picnic table behind us. ‘If you keep giving everything away, Hugh, it’ll be my name over your door before long.’ I glanced over my shoulder. He was smiling at Mr Jones, but Mr Jones’s timid features were flushed. Father had told us the grocer wasn’t collecting on the accounts of families that were struggling to put food on their tables. He was a true Christian, Father said. Mayor Lloyd reached for another roll from the bread basket.

Mother and Father sat at a separate table with the Williamses and the Lewises. Father and Mr Williams had grown up together, the sons of best friends, and Mrs Williams and Mother had become close over the years of their marriages. As usual, Mrs Williams was doing most of the talking in her quick, laughing voice while Mother nodded and Father rested his elbows on the table, his dark eyes quiet. Like us, he’d spent his childhood summers at this lake, and the tension that always simmered in him seemed to ease when he was here.

Emily sat between Mother and Father, her feet dangling almost but not quite to the grass. She rarely played with the other children, either. She was a serious child, not inclined to play the kinds of games children that age play, and even had she been, she was Mother’s pet, so Mother kept her close. In fact, in her six years I don’t believe she’d made a single friend. I suppose that’s why, before long, Mother, Lilith, and I were the only ones who remembered her as anything other than a local mystery. Aside from Abe Miller, of course. Though he would never speak of her to us.

As the kick-the-can game got under way, Emily left Mother and Father and slipped onto the bench beside Lilith. She adored Lilith, although Lilith paid her almost no attention and the little she did pay was invariably unkind. Now Emily sat, hoping to catch Lilith’s eye. Lilith and I refused to give her a single glance.

In the course of the game the can rolled close to us, and big-faced Charlie Lloyd chased it down. He was fifteen, with his father’s heavy good looks but none of the politician’s easy manner. The summer before, he’d sent Lilith a love note that we burned in the kitchen sink, watching with satisfaction as the plaintive phrases turned to ash. Now he gave Lilith a shy glance over his shoulder as he ran back to the game. I expected to see disdain on her face, but to my surprise she smiled at him, a close-lipped smile that tilted higher on one side. Charlie’s face blazed red and he tripped over his feet.

Jeannette Lewis, one of the nearby girls, saw this, and said something to Charlie’s twin sister, Betty. Betty’s rosy apple face dimpled at Lilith with a new, calculating regard that I didn’t like. Lilith looked straight ahead, that smile lingering, her long, silky curls gleaming. All the teenaged girls wore their hair in bobs that curved around their ears to the collars of their dresses. I knew Lilith was desperate to cut hers, too, and that Father would never let her, but I thought her long hair was much prettier than their blunted locks and that she looked, with her odd smile and strong features, older than any of them at that moment. With my unruly, sand-colored hair and my dirty feet, I felt like Emily: an unwanted, tagalong little sister.

I leaned around Lilith to where Emily sat. She straightened, her eyes hopeful. ‘Go away,’ I told her, my voice as vicious as I could make it. She blanched, then slid off the bench and ran back to Mother and Father. I felt the slippery, cold satisfaction I always felt when I hurt her. I glanced at Lilith, hoping for an approving smile, but she was still looking at Charlie. Behind us, Father lifted Emily onto his lap. Over her dark ringlets he watched Charlie, too.

I imagine we don’t seem unusual to you as I’ve described us on that first summer day. We were an oldest sister growing up, and a middle sister being left behind. A youngest sister wanting to belong. A father watching a boy who flirted with his daughter. Nothing you wouldn’t see in countless other families. But if I am to tell you the story of what happened to us, I must start at the beginning. And in these few things, ordinary as they may seem, lie the beginnings of everything that came after.

Justine

She wasn’t thinking of leaving him. Why would she? He was everything she wanted; everything Francis, her daughters’ father, had never been. He was faithful. Reliable. Home every night at five thirty. And he made her feel safe. Especially after the burglary. She was lucky to have a man like him when there were people out there with lock picks and violence on their minds. At least, that’s what she told herself as she lay awake beside him the night after it happened.

The police said the burglars must have been watching the apartment building, because their timing was perfect. Justine had picked up Melanie and Angela from the elementary school aftercare on her way home from work as usual. Then, five minutes after they walked in the apartment, Angela said she needed supplies for a school project – poster board and colored pipe cleaners. Patrick wasn’t home yet, so Justine left a note saying she’d be back at six and would bring takeout. They went to the Walgreens and the In-N-Out and got back at six exactly.

As soon as they walked in the door Justine stopped, instinctively pressing the girls backward. The apartment was completely trashed. The sofa was on its back, its cushions off. Both lamps were on the floor. The coffee table was tipped over, and magazines were everywhere. In the kitchen the cupboards stood open, their contents emptied on the counters, and pots and pans covered the linoleum.

Patrick’s black messenger bag, the one he took to work, sat in the hallway at Justine’s feet, but he wasn’t in the kitchen or the living room. ‘Patrick?’ She called, in a half-whisper. There was no answer. The air went thin around her. ‘Run!’ she hissed to the girls. ‘Go to Mrs Mendenhall’s! Tell her to call the police.’

Melanie and Angela fled back to the landing and down the stairs. Carefully, Justine lowered the shopping bags to the carpet. She stepped into the living room, every muscle tensed. She called Patrick again. Again there was no answer. She crept down the hall to their bedroom, her back pressed against the wall. She held her breath and peeked inside. The covers were off the bed and clothes spilled out of the drawers, but no one was there. Across the hall, the girls’ room was the same. No one was in the apartment.

Justine ran back to the living room, panicking now. Where was he? Had he been here when the burglars came? He must have; otherwise he’d be here now. She pressed her hands against her head. They’d done something to him. They’d taken him. Or he’d chased them and they’d hurt him. She heard the distant whine of a police siren. The police would find him. She would meet them in the parking lot.

She turned toward the door and jumped, a scream in her throat.

Patrick was standing in the doorway, watching her.

‘Patrick! Oh, my God!’ She staggered with relief – he wasn’t hurt; he didn’t have a mark on him; he was safe. She ran to him, tripping over the sofa pillows, kicking one of the lamps, falling against his chest. His arms swallowed her as she inhaled the tang of his sweat and the acrid scents of ink and toner, sobbing into his white work shirt. His fingers dug into her ribs as though trying to unlock them.

‘It’s okay,’ he murmured into her hair.

‘I was so scared.’

‘Me, too.’ His voice was tight. ‘I came home, and you were gone.’

She raised her head and saw in his taut, pale face what he’d been through. He’d come home at five thirty, as he always did, and found the apartment wrecked, and her gone. With her note buried in the mess, he hadn’t known she and the girls were safe, buying pipe cleaners at the Walgreens. The errand might have saved their lives, but she knew what it had done to him to walk into the ruined, empty apartment. He’d thought his worst nightmare had come true.

‘Patrick, I’m so sorry.’ She embraced him again, tenderly this time. He sagged against her. They stood for a long time like that, his weight heavy on her. When her back began to ache, she eased him away, kissing him in solace. His cheeks were soft, like a baby’s. After the police had come and made their notes and dusted for fingerprints, Justine and Patrick cleaned up the mess and made a list of what was missing: the television, the VHS player, Justine’s few earrings and necklaces. Then, while Justine retrieved the girls from Mrs Mendenhall and fed them their cold In-N-Out burgers, Patrick drove to the twenty-four-hour CVS and bought a new lock that he installed himself. It took the girls a long time to settle into sleep, but once they did, Justine and Patrick made love like survivors in the tangled sheets of their bed.

Afterward, Justine lay with Patrick’s arm heavy across her waist and watched the digital clock measure out the minutes in silent red lines. He made her feel safe. He did. But something about the burglary niggled at her. Part of it was the enormity of the mess – why would a burglar flip over the sofa and strip the beds? – but it wasn’t just that. Finally, as the sky lightened toward dawn, she put her finger on it: it wasn’t how excessive the violence had been, but how orderly. The lamp shades had still been on the lamps, even though the lamps lay sideways on the floor. The pots and pans were stacked on the linoleum as if set there rather than tossed. Things were missing, but nothing had been broken.

She thought, too, about how she hadn’t left her note on the counter but on the kitchen table, which wasn’t really in the small kitchen but practically in the living room, where Patrick might not have found it right away. For a few minutes, when she’d been at the Walgreens and her note wasn’t in plain sight, he might not have known where she was.

She drew her legs to her chest. Patrick always wanted to know where she was, insisted upon it, even. It was one of the things she found most endearing about him, after Francis’s painful disinterest those last years. She stared at the gray light that came through the gaps in the oatmeal curtains that had come with the apartment. Where had Patrick been when she got home? When she called his name, fear making her voice tremble and crack? How long had he been standing in the doorway, watching her?

Outside, birds began to chirp and chatter. Patrick’s body, curled around hers, was warm and solid and reliable as always. What was she thinking? That he’d staged an elaborate burglary just to make her feel what he’d felt when he came home and she wasn’t there? To see if she would feel it? Because that would be crazy. This was Patrick. Dependable, meticulous Patrick, who couldn’t abide any sort of mess and never raised his voice to her, much less a hand. She was thinking like her mother. Her mother, to whom every man was a prince – until he was a liar, or a pervert, or a nutcase, and she had to leave town. She wasn’t her mother. She’d found a good man. She felt his breath on her shoulder and forced her suspicion to hold its tongue.

But the next day, she left him.

That day started like every other day since he’d moved in ten months before. Justine got up first, even though she’d barely slept, and spent half an hour sitting in one of the Windsor chairs at the kitchen table with her knees pulled up under her chin and her eyes closed. She’d done this every morning since she was a girl, sitting alone while her mother slept, storing up silence against the noise each day would bring. If she listened, she could hear the low voices of the couple next door, but she didn’t. She listened only to the quiet of her own apartment in the pale light.

When Patrick’s alarm went off, she woke her daughters for school and made breakfast. When Patrick appeared, he ruffled Angela’s hair and said good morning to Melanie. Justine stood on her tiptoes to kiss him, and he didn’t smell like sweat and toner; he smelled of Irish Spring and Walmart laundry detergent, the fresh-bitter scent she associated with him. By the light of day, in the tidy kitchen that bore no traces of the burglary, her nighttime suspicions seemed even more preposterous.

He had his eggs over easy, as always, and as always he told her they were great. She’d learned to make them exactly the way he liked. He needed his eggs done exactly right because he sold office equipment at the Office Pro, mostly desktop printers and other small machines. When he proved himself, he could sell the copiers, which was where the big money was, because once you sold one you got to sell the paper and toner and ink that went with it, forever, but his boss wouldn’t let him do that until he got his quarterly numbers up, and to do that he needed the eggs. After he ate he wrapped her in a hug and tossed his keys in the air as he walked out. Just like any other day.

On her way to work, she dropped her daughters at the elementary school. She watched Melanie trudge to the blue doors and wondered if she was going to get another call from the assistant principal that afternoon. Her eldest had been surlier than usual, even disobedient, and last week there’d been shoving on the playground during which another fifth grader’s backpack had landed in the mud. The assistant principal said if it didn’t stop there’d be counseling, maybe special classes. Justine watched with a frown as Melanie climbed the steps with her shoulders hunched like a tiny boxer. Then she drove to Dr Fishbaum’s office, where she was the receptionist, and she didn’t think about anything but work until lunchtime, when her mother called and everything changed.

She answered, assuming it was one of Patrick’s check-ins – it was why he’d given her the cell phone, an expensive luxury in 1999 – but instead her mother’s voice breezed in from Arizona or New Mexico or wherever she was now, cruising the warm lands with her latest boyfriend. Justine hadn’t seen her in three years, but Maurie called every couple of months and, of course, she sent all those postcards – pictures of beach towns and mountain towns and desert towns with a scrawl on the back: ‘Mesa is wonderful!’ ‘Gotta love Austin!’ Justine threw them away immediately. Now she rubbed her left eyebrow, where the headache a call from her mother always awoke opened its tiny eyes.

At first Maurie chatted on in her usual way about Phil-the-boyfriend, the RV park, and how she was learning to play golf, and Justine’s attention wandered to the stack of patient files on her desk. She wasn’t supposed to read them, but she liked the small, ordinary stories they told, so she opened the top one. Edna Burbank, 84. Arthritis, bursitis, a prescription for Xanax.

Then Maurie said, ‘Do you remember my aunt Lucy? Up at the lake?’

Justine closed Edna’s file and sat forward in her chair. She hadn’t thought about Lucy for years, but at the mention of her name a riot of memories broke out in the front of her brain. When she was nine, Maurie had driven them to a lake in northern Minnesota where there were green trees, clear water, and blue nights filled with the sound of crickets. They’d lived in a yellow house with a screened-in porch with three women: Aunt Lucy, Grandma Lilith, and their mother, her own great-grandmother. ‘Yes. Yes, I remember her.’

‘Well, she died. I just got the notice. Thank God I set up the forwarding this time.’ Ice clinked in Maurie’s glass. ‘She never should have stayed in that house by herself. After Mother died I told her she should move to the retirement home over in Bemidji, but she wouldn’t. God knows how she made it through those winters.’

Justine had loved that lake. Not only because it was beautiful, but also because Maurie laughed differently there. Instead of the brittle laughs Justine had heard in the diners and cheap cafés that crowded her memory, Maurie’s lake laugh let you see all the way to the back of her mouth. She’d seemed different in other ways, too. Relaxed. Not looking ahead to the next big adventure. For a while Justine even thought they might stay, that they might live there longer than the few months they spent in most places. But in September they piled their things in the rusty Fairmont and drove away. Off to Iowa City, or maybe Omaha. She couldn’t remember. Another apartment, another job, another boyfriend, another school.

Still, all that next year, Justine hoped they’d go back. Maybe it would become a tradition that they went to the lake every summer. Other people had traditions like that, she knew. But she never brought it up, and when summer came and went with no mention of the lake she wasn’t surprised. After all, Maurie never went back anywhere. When they left a town she wouldn’t even let Justine look back at it. ‘Shake the dust off,’ she’d say. ‘Shake the dust of that town off your feet.’ She’d take her foot off the gas and shake both feet and Justine would, too, even though she never wanted to leave, no matter where they were.

‘When did Grandma Lilith die? You never told me.’ Justine wondered what Maurie had done when her mother died. Had she gone back then? Would she have broken her rule to see her mother buried?

Maurie ignored her. ‘The letter was from some lawyer. Turns out Lucy had some jewelry of Mother’s she wanted me to have. And he wanted your number.’

‘Why?’

‘Well. Apparently she left you that house.’

‘She what?’ Justine had to tighten her fingers to keep from dropping the phone.

‘Not that it’s worth much, stuck up there in the middle of nowhere.’ The ice clinked again. ‘She always wanted me to come back. Your mother misses you, she’d say. But my God, it was awful growing up in that place. Nobody lived there, just the summer people who didn’t give a crap about some local girl. I got out as soon as I got my driver’s license.’

It had never occurred to Justine that the lake house was where her mother grew up. Maurie rarely talked about her childhood, and as an adult she was such a creature of the road that Justine had always pictured her screaming her way into the world in a caravan somewhere, a modern-day gypsy. ‘Minnesota,’ was all she’d say when anyone asked where she was from, somehow making an entire state sound like a bus stop. Now Justine remembered her lying on the porch swing at the lake house as the sun, silty with motes, spilled through the front windows onto golden pine floorboards. Her hair was in a loose ponytail, her face was young, and she laughed with her mouth wide open.

But Lucy had left the house to Justine.

The elevator chimed. Phoebe, the office manager, was back from lunch.

‘Mom, I have to go,’ Justine said. ‘Do you have the lawyer’s number?’ She wrote it down and slid the phone back into her purse just as Phoebe opened the office door. ‘Angela’s sick,’ she said to her, without meeting her eyes. She’d never asked to leave early before.

Phoebe sighed. She didn’t much care for Justine, but she had a fatherless child of her own, so she said she’d cover the desk. Justine walked out without looking back.

In the apartment she paced, holding the phone in one hand and the lawyer’s number in the other. Finally she sat at the kitchen table, pulled up her knees, and closed her eyes, as she did during her morning minutes. Only this time she couldn’t hear the silence. Instead she heard the low hum that came from the refrigerator, the fluorescent lights, the clock on the wall.

The apartment was crappy, of course. The walls were scuffed, the carpet was matted, and the sliding door was held shut with duct tape. Still, it was the only place she’d lived since she stood with one hand in Francis’s and the other on her belly, where the secret clot of cells divided and grew, and told her mother, who’d decided to give Portland a try, that she was staying in San Diego. She was eighteen, Francis nineteen. They’d picked it because it was the closest place to the ocean they could afford. Eight blocks, so not that close, but when she stood on the balcony at night with Melanie in her arms Justine could hear it whispering beyond the low-slung buildings that made up their neighborhood. The night they moved in they drank champagne out of paper cups in the empty living room. The worn nap of the carpet was soft on Justine’s shoulders as they made love, and she’d sworn she’d never leave. That her child would grow up in one place, whole.

She opened her eyes. Patrick’s coffee cup, half empty, sat on the table.

She dialed the lawyer’s number. Just to find out what was going on. To see if her mother had her facts straight, which wasn’t a certainty by any means.

The lawyer’s name was Arthur Williams. He and his uncle before him had handled the Evans sisters’ affairs for decades, he said. Lucy had died three weeks before, in her sleep. It had been sudden but peaceful, and her neighbor had found her the next day. His voice was soft, the consonants that bracketed the broad vowels crisp.

Justine pressed the handset against her ear. ‘My mother said you wanted to talk about Lucy’s will?’

‘Yes. You’re her sole beneficiary.’ This meant, he explained, that Lucy had left Justine everything she owned, except the jewelry she’d left for Maurie. The house was old and in need of updating, but it was unencumbered by any liens. Lucy had a checking account and an investment portfolio, too; he would fax her the details.

‘How much is in the accounts?’ Justine asked, then wished she could take the question back. It sounded like something her mother would ask.

The lawyer answered as though it were a perfectly acceptable question. The checking account had about $2,000, and the investments were mostly stock and worth about $150,000. ‘You might want to come and settle things in person,’ he said, ‘if there are things in the house you want to keep. Or you can contact a lawyer where you are, and we’ll handle the probate by fax. Then I can recommend a realtor to sell the house for you.’

He paused. Justine knew she was supposed to say something, but her head felt as if it would float straight up and away if she didn’t hold on to it. There was $150,000 in an investment portfolio somewhere in Minnesota. She and Patrick had $1,328 in their account at the Wells Fargo. The lake house had been the color of butter in the sun.

‘Can I call you back?’ she asked. Of course, he said.

When she hung up she took Patrick’s coffee cup to the sink. She washed it and dried it and put it in the cupboard. Then, from the storage unit in the basement, she pulled the faded blue duffel she’d kept from when she was her mother’s daughter. In it she put her jeans and the three sweatshirts she owned. Two pairs of shoes that weren’t sandals. Bras, underwear, socks, pajamas. Toothbrush, shampoo, hairbrush. She zipped up the bag and put it by the front door.

From beneath the sink she took a stack of brown grocery bags. In them she put the photo albums she’d made when the girls were babies and the more recent snapshots magneted to the refrigerator. From inside the refrigerator she took bread, peanut butter, and jelly. From the pantry, crackers, chips, and cereal. At two thirty Patrick called on her cell. She stood motionless in the apartment as he crowed about his day: two fax machines and a printer sold before his lunch break. When he asked what was for dinner, she told him they had leftover spaghetti. He asked her to pick up that garlic bread he liked on her way home. She said she would.

After they hung up she called the lawyer. ‘We’re coming,’ she said. He sounded pleased. He gave her directions and told her Lucy’s neighbor, Matthew Miller, would have a key to the house.

Her daughters didn’t have suitcases, so Justine took the pillowcases from their beds and filled them with their warmest clothes and shoes. Then she used more brown bags to hold their jewelry boxes with plastic ballerinas inside, stuffed animals, plastic horses, dolls with tangles in their hair. Barrettes and scrunchies, drawing paper and markers. She put the bags by the front door with the rest. It didn’t look like much, but it filled the back of the Tercel.

When she finished loading the car it was four thirty. She was supposed to pick up her daughters at the aftercare at five. At five thirty, Patrick would be home.

She put her apartment key on the kitchen counter and her cell phone beside it. She pulled a Post-it off the stack. The clock inched forward another minute while she debated what to write. Francis’s note had said he was sorry. She didn’t know if she was sorry. She didn’t know what she felt, other than a buzzing anxiety pegged to the sweep of the second hand around the clock face. In the waning November afternoon the living room furniture she and Francis had bought on layaway looked dark and strange, as though it had never belonged to her at all. A shiver ran across her shoulder blades. She’d forgotten how easy it was, to slip out of a life.

Dear Patrick, she wrote, the spaghetti is thawing in the refrigerator. She laid the note on the counter, smoothed it once, and walked out. Her feet on the steps were light. When she reached the bottom she heard her cell phone ring, faintly.

Later she wouldn’t remember driving to the school. But she would remember that her face felt like dried icing as she walked her daughters to a picnic table on the playground and told them they’d inherited a house on a lake that had a porch and a swing, and that it was in Minnesota, but that was okay, because they’d get to see things along the way, like the Rocky Mountains and Las Vegas, and it would be an adventure.

The girls stayed quiet until she was done talking. Then Melanie’s eyes narrowed. ‘Wait. Are we moving there?’

Melanie was not an attractive child. At eleven she’d long since lost her baby fat, revealing severe features and a too-long nose that rode high into her wide brow and gave her a haughty air. Now her suspicious frown made her look small and cunning, like a fox.

Justine forced her voice to remain even. ‘It’s a house, sweetie. We’ll have a great big house just for the three of us, with a lake right out front. For free.’

‘The three of us? What about Patrick?’

‘I thought it might be good to be on our own for a while, just us girls.’

Melanie’s frown deepened. Angela looked stunned. Both girls’ arms in their short-sleeved shirts were thin and straight and brown from the San Diego sun. Behind them Justine could see other parents picking up their children. Taking them home for dinner, then homework at the kitchen table, maybe some television before bed. ‘I’ve got all your stuff in the car.’

‘We’re leaving now?’ Melanie’s voice slid up half an octave.

‘I know it’s sudden. But it’s better this way. A clean break.’

‘What about Daddy?’ Angela said.

Justine opened her mouth and shut it again. Francis had been gone a year, and they hadn’t heard a word from him in all that time. Neither girl had asked about him in months. After Patrick moved in, the picture of Francis and the girls at Coronado Beach had disappeared from the girls’ room. She’d thought this meant they were shaking him off their feet like dust, the way Maurie always told her to, the way she was trying to, but the hitch in Angela’s voice told a different story.

Melanie said, ‘Daddy’s not coming back, you idiot.’ She looked at Justine, her eyes flat. Justine muffled a flare of anger. Her eldest daughter’s sullen temperament and brusque manner often made Justine dislike her, something she felt ashamed of and guilty about. Besides, this time she knew it wasn’t Melanie she should be mad at. Toward the end Francis had hardly come home at all, but that hadn’t diminished his daughters’ love for him. The opposite, in fact.

Justine put her hand on Angela’s arm. ‘I’ll tell Mrs Mendenhall where we’re going, and if Daddy comes looking for us, she can tell him.’ This was a lie. She wasn’t going to tell Mrs Mendenhall anything. Mrs Mendenhall liked Patrick.

Angela’s eyes filled with tears. ‘What about Lizzie and Emma?’ These were Angela’s best friends, the three of them the most popular girls in the second grade.

Justine’s tongue tasted like metal. She remembered how she would come home from school to find her mother sitting at the kitchen table with her cigarette and her can of Tab. ‘Sit down,’ Maurie would say, and Justine would know they were leaving.

‘We can send them postcards when we get there, sweetie,’ she said, just as her mother had.

Angela looked back at the school. Through the open door of the aftercare center Justine could see children coloring and playing with LEGOs. Angela’s face puckered, and Justine’s simmering anxiety bubbled into panic. It was five thirty. Patrick was walking into the empty apartment right now. Would he come to the school? He probably would. A familiar, claustrophobic sense of failure mixed with her panic, making the world seem small and tight. What was she thinking, doing it like this? She should have waited until tomorrow. Kept the girls home from school, had them help her pack. It would have been easier on them. And easier for her to get them in the car.

Then Melanie stood up. ‘Angie, you know what? It sounds like fun to live on a lake. And Lizzie and Emma can come visit.’ Justine watched in mute astonishment as she continued, ‘Plus you’ll go to a new school and you’ll make all new friends. You’ll be the most popular girl in class because you’re so pretty. And maybe’ – she shot a dark-eyed glance at Justine – ‘you can get a kitten.’

Justine leaned forward. ‘Of course! We can have cats, dogs, whatever we want.’

Angela’s face was a study in misery. She’d wanted a cat ever since she was small, but Francis had been allergic, and Patrick, the farmer’s son, thought cats belonged outside.

‘Come on, Angie.’ Melanie reached out her hand. After a precarious moment Angela swallowed a throatful of snot and tears and took it. Justine tried not to show her limb-loosening relief as she rose to follow them.

An hour later they were on Highway 15. None of them said a word as they drove through the California dusk into the Nevada night. She could hear her mother’s voice, braying over the wind that whistled through the open windows of the Fairmont: ‘See any place that looks good, honey?’ In the rearview mirror the salvage from their apartment crowded the Tercel’s back bay, looming like a slag heap over the small forms of her daughters. She forced her eyes forward, to the yellow ribbon that unspooled before them.

Lucy

It’s hard for me to remember what Mother looked like then. She was slender, I do remember that, with blue eyes and curly light brown hair she wore in a snood. Sometimes I heard people say I looked like her, and sometimes I heard them say she could be pretty if she tried, but I didn’t want to look like her and I didn’t think she could ever be pretty. Although I will grant that she had fine bones – years later, her cheekbones and jaw made delicate craters into which the flesh of her face sank – what I remember most are her hands: chopping, kneading, washing, mending, combing. How the tendons worked as she made her samplers, or picked at the quilt that covered her when she was dying.

In the kitchen the morning after we arrived, her hands were wet with soap as she scrubbed the pot she’d used to make our oatmeal. Father was fishing, so it was just us girls for breakfast. Lilith and I filled our bowls and sat at the table, Lilith’s face a portrait of martyrdom, and mine, I’m sure, its studied mirror. We knew what awaited us: every year we had to spend the first full day of summer cleaning the house. But this year I felt a relieved pleasure beneath our shared misery, because it tasted the same as always, and as always it belonged only to us. Emily never had to help with the cleaning. She never had to do any chores at all, an inequity that had rankled us for years. Just looking at her that morning, immaculate in her pink flowered dress and matching hair ribbons, was enough to raise bile into our throats.

Lilith spooned up a large bite of Emily’s oatmeal and ate it. Emily looked at Mother, whose back was to us, but didn’t say anything. Lilith laughed, and so did I.

After breakfast, we worked. We washed the curtains, beat the rugs, and wiped the cupboards clean of the curled-up insects that had died there during the winter. We scrubbed with Borax, swept under bureaus and beds and parlor furniture, and dusted the tops of the picture frames. Father was fastidious, so Mother kept a nice house in those days. She checked our work, found dust we missed, and told us to do it over. She said it kindly, though, and promised us ice creams at the end.

At first Emily crept along behind us, her eyes always on Lilith, but when we got to the upstairs bathroom, Lilith pushed her backward hard enough that she nearly fell. ‘Stop following us,’ she said, and shut the bathroom door in her face. After that, Emily gave up and went back to Mother. Then Lilith’s mood lightened, and she started to do one of the things I loved most about her: she made things fun. She staged contests to see who could clean the bedroom windows faster (she won), and who could hit the Lewises’ house with the dirty water we threw out the window from our buckets. We pretended we were Cinderellas, slaving away in anticipation of our princes, and Lilith used a funny British accent as the voice of the evil stepmother, and I could barely breathe for laughing. We hadn’t played like this in a while, and as we scrubbed I shared in the pleasure the house seemed to feel in shedding the dirt of winter. Once our cleaning was done, we would go to the Hundred Tree, and summer would begin in earnest.

We were mopping our bedroom floor when we heard Father return. At the sound of his voice we both stopped, listening as his feet came light upon the stairs in that quiet way he had. When he reached the landing, he paused in our doorway.

Mother’s long-ago appearance may be hard for me to recall, but I remember Father’s as though I saw him yesterday. This is partly because, unlike with Mother, my memory of Father in his youth wasn’t displaced by the image of him in his old age, but it’s also because no one who met Father forgot him. It wasn’t that he was handsome. His face was narrow, and he was shorter than most men, with spare bones. It was his eyes, which were deep-set, with bottomless dark irises that seemed unusually large, like those of babies. Like a child’s, too, they looked at you for longer than was comfortable and seemed to see things that others did not. I used to love it when he looked at me.

That morning, though, he looked only at Lilith, and he frowned. She’d fastened a skirt to her head so it hung down her back – it was part of her Cinderella costume – and the makeshift wimple gave her fine cheekbones and arched brows a proud austerity that made her look, to me, every bit the beautiful servant girl destined to be a queen.

‘Take that off,’ he said.

Lilith’s shoulders twitched in the smallest of flinches. I didn’t know why he was upset with her; we were just playing, and our game was the innocent, pretend sort of play he’d always told us God loved to see. Lilith dropped her eyes, pulled the skirt from her head, and went back to mopping. Her long hair fell forward, hiding her face.

I expected Father to leave us then, but instead his eyes slid to me. He didn’t look at me often, and the unaccustomed weight of his attention slackened my fingers so that my mop clattered to the floor. My face burned as I bent to pick it up. When I stood, he was gone, into his bedroom to change. Lilith and I went back to our cleaning, but we didn’t play anymore.

After we finished, I wanted to go straight to the lodge for our ice creams, but Lilith made me wait while she changed into a blue plaid dress and brushed her hair. Only when she’d checked herself in the mirror for the fourth time did we go to the kitchen, where Mother was cleaning the walleyes Father had caught. Her bloody fingers were quick with the knife, and a pile of severed heads stared dully from the counter. Emily stood on a chair, watching.

Mother brushed her forehead with the back of one hand and gave us a tired smile. ‘Go get your ice creams, and get those things for me. Take Emily with you.’ She motioned to the table, where a five-dollar bill sat next to a grocery list. Lilith put it in the small blue purse she’d selected to match her dress, and we went out the back door.

We didn’t want to take Emily, of course, and we didn’t think she deserved an ice cream, so we walked faster than her legs could go. Lilith glanced at our neighbors’ houses as we passed, and I was peevishly glad no one was out to see her parading in her summer glory. The happiness I’d felt during our cleaning, which even Father’s disapproval of Lilith’s costume hadn’t erased, dissipated into the dust that clouded our feet, hers in trim white sandals and mine in dirty Keds. The moment she’d changed her clothes I’d known we weren’t going to the Hundred Tree.

The lodge was the only commercial structure on the lake, so it served many purposes. On the second floor were rooms for the fishermen who drove up from the lakeless counties downstate. Downstairs, a screened-in porch ran across the front, with couches and chairs and two pinball machines. Behind that was a big, high-ceilinged room with a bar, a pool table, an old upright piano, a half dozen tables, and, in the far corner, shelves that held a dusty collection of souvenirs and the most basic of groceries.

It was empty when we arrived, but as we gathered our groceries Abe Miller pushed open the kitchen door. The night before, when the Millers served our supper by the lake, I hadn’t paid him any attention, but now I saw how much he’d changed since the previous summer. He must have been fifteen then, and he’d gotten his growth; he was taller than Father now, with large hands dangling several inches below his sleeves. His black hair was cut short, and his face had lost its childish softness, revealing strong features with a straight nose and full lips. To my horror, Lilith smiled at him – a close-mouthed smile that canted up on one side, like the one she’d given Charlie Lloyd.

Abe’s swarthy skin reddened. ‘Can I help you?’ His voice was slow, the consonants labored, the way it had always been, but now it was the deep voice of a man.

The kitchen door opened again, hitting his shoulder. Matthew, the younger brother, nearly dropped a heavy tray stacked with coffee cups, and blurted out a word I’d only heard grown men use when they thought children couldn’t hear them. Abe took the tray and carried it easily to the bar, his shoulder muscles knotting beneath his white shirt.

Matthew saw us, and wiped his hands on his apron. ‘Do you need anything?’ He stammered a little, no doubt remembering his curse word of a moment before. His head was lowered, and he looked at us through straight black bangs.

Lilith and I hadn’t had much to do with the Miller brothers before that summer. The little I did know about them came from overheard talk among the grown-ups: their father was a white man from Williamsburg who’d married a woman from the local Chippewas, and after they’d both been cast out by their tribes they managed to get property along the lake and build this lodge. The lake families disapproved of them, of course, but they liked the lodge’s amenities, so the women smiled at Mrs Miller when they bought their groceries, and the men shook Mr Miller’s hand when they rented their fishing boats.