Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

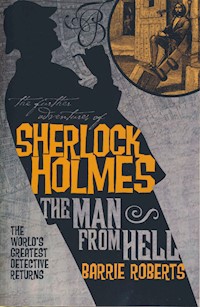

The brutal murder of the reclusive Lord Blackwater propels Holmes and Watson into another intriguing case that points to the shadowy figure known only as "The Man form the Gates of Hell". A tangled web of deceit, violence and tragedy unravels as Holmes' deductions bring him closer to those behind the plot-a criminal organisation with a far-reaching and perilous influence...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 272

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AVAILABLE NOW FROM TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE ECTOPLASMIC MAN

Daniel Stashower

ISBN: 9781848564923

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE SCROLL OF THE DEAD

David Stuart Davies

ISBN: 9781848564930

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE STALWART COMPANIONS

H. Paul Jeffers

ISBN: 9781848565098

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE VEILED DETECTIVE

David Stuart Davies

ISBN: 9781848564909

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

Manly W. Wellman & Wade Wellman

ISBN: 9781848564916

THE MAN FROM HELL

BARRIE ROBERTS

TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES THE MAN FROM HELL

ISBN: 9781848565081 (print)

ISBN: 9781845869140 (eBook)

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First edition: February 2010

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 1997, 2010 Barrie Roberts

Visit our website:

www.titanbooks.com

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address. To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive Titan offers online, please register as a member by clicking the ‘sign up’ button on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

CONTENTS

Foreword

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Ninteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Author’s Notes

Also Available

Foreword

The circumstances in which I came into possession of what seems to be a quantity of manuscripts by the late Dr John H. Watson have been explained in an earlier publication –Sherlock Holmes and the Railway Maniac. Briefly, they appear to have been in the possession of my maternal grandfather, who was both a medical man and a contemporary of Watson’s in the RAMC.

In preparing the present manuscript for publication I have made such checks as have occured to me, to try and confirm its authenticity. The results of my researches will be found in a series of notes appended to the narrative. Suffice it to say, at this point, that I am as satisfied as I can be that this is a case of Sherlock Holmes’ recorded by his partner, Dr Watson, of which nothing was formerly known, apart from a couple of passing references in the Doctor’s published records.

Barrie Roberts

1996

One

THE DEATH OF A PHILANTHROPIST

In looking over the many records I have prepared of the cases of my friend Mr Sherlock Holmes, I find that I have not given his followers an account of the Backwater murders. That I did not do so earlier was for two reasons. In part it was because the story is one that embraces both appalling cruelty and corruption. In addition it was to avoid embarrassment to the living and to prevent the circulation of information which the ill-disposed would readily use to besmirch the memory of one of the Empire’s greatest philanthropists. Indeed, my use of the pseudonym Backwater is still necessary, for the principal victim in that unhappy affair bore a name which may yet be read on memorial plaques and on the foundation stones of charitable institutes across the nation. Nevertheless, the resolution of the case was one which afforded my friend Sherlock Holmes no little satisfaction and removed a deep-rooted and secret evil from our public life, and so this manuscript has been prepared with due consideration for the privacy of those involved, while setting out the essential facts of the case.

My journal shows that it was the early summer of 1886 when the Backwater matter came to Holmes’ attention. It was during the first period of our shared residence at Baker Street and I had become well aware of the irregular habits of my companion. Despite my lack of an occupation, I endeavoured to maintain a fairly orderly regime, but my efforts were brought to nothing by the moods of my friend. If I rose early it would be to find that he had not been to bed, or that he had slept late and would take his breakfast at an hour more suitable for luncheon. Yet when the exigencies of a case demanded it, he would rise early and alert and set out about his business.

There were mornings when he surprised both Mrs Hudson and me by being early at the breakfast table when he had no enquiry in hand. On those days he seemed to expect action and would go through the newspapers thoroughly and read his post as though a summons was imminent. If the papers or the post showed no indications, and if no prospective client’s foot had been heard on our stair by mid-morning, he would take himself off to the British Museum to pursue his arcane researches into early British charters or ancient languages. I came to believe that this behaviour derived from an excess of energy at the completion of a successful case, and I noted with misgivings that the phenomenon disappeared when he took to poisoning himself with cocaine.

It was one such morning when the Backwater case began, a bright morning when the sun struck deep into our little sitting-room. Holmes’ early rising had not taken Mrs Hudson by surprise and, having finished breakfast, he turned over the newspapers.

‘Lord Backwater has been murdered!’ I exclaimed, seeing a notice to that effect in my paper.

‘So I see,’ said Holmes from behind his own newspaper, ‘and one paper has a leader arguing that it is evidence of a completely disordered and unjust universe that a man who has given employment to thousands, hugely enriched the nation and has never stinted in his donations to the unfortunate should be struck down by poachers.’

‘Is that what occurred?’ I asked. ‘There are few details here.’

‘There are longer accounts in some of the papers,’ said my friend. ‘It seems that he was strolling in his own park when he disturbed poachers about their work and was savagely attacked.’

‘Then it has no interest for you?’ I asked. ‘Despite the man’s wealth and eminence?’

Holmes eyed me over the top of his newspaper. ‘I am surprised,’ he said, ‘that you do not appear to realise that the personality or antecedents of a victim are of interest only insofar as they may reveal the motive for a crime. If the police in the West Country are correct then it is of no significance that it was Lord Backwater who disturbed a band of poachers; they would just as readily have murdered you or me.’

‘It seems a very cold-blooded attitude to me,’ I admitted.

He laughed shortly. ‘Would you consider a patient’s personality or history when treating his wounds, Doctor? If they did not assist your diagnosis or affect your treatment? No, Watson, you treat the diseases of the individual and I treat the irruptions of society and neither of us can allow our approach to be clouded by sentiment, however worthy.’

He flung his newspaper into the seat of the basket-chair and drained his coffee. Standing up, he stretched his long, lean frame and sauntered over to the sunlit window. The morning deliveries had been made and the day’s business had not yet begun, so that the street was quiet, apart from the rattle of a solitary cab. ‘You may abandon the newspapers,’ he said. ‘There is nothing there of interest.’

‘It is what journalists call “the silly season”, Holmes,’ I ventured.

‘A gross misrepresentation!’ he snapped. ‘There is a world of difference between silliness and the arrant imbecilities that obsess the whole of Fleet Street at present. The established press comforts itself and its readers with the information that nothing of any consequence has changed since yesterday – regarding this as “news”! The radical papers treat the same facts as evidence of a stagnant society and the popular sheets invent and repeat unprovable assertions about the private life of the Queen’s family! Rubbish! All of it!’

‘I had thought that the items about the Duchess–’ I began, but he cut me short.

‘...might once have produced an interesting commission for us,’ he growled, ‘but that is no longer likely when the lady’s indiscretions are the common tattle of every Bermondsey barmaid!’

He stared moodily out of the window, evidently disappointed that he had risen early to no purpose.

‘I believe,’ he said, after a moment, ‘that we have some early business. What do you make of the couple across the street?’

I joined him at the window and followed his pointing finger. On the opposite pavement stood two gentlemen who had just dismounted from a cab.

‘The younger man is dressed both discreetly and expensively. He stands back while the older man pays the cabby. I surmise that the elder of the two, who is dressed in a more workaday fashion, is some senior assistant to the younger – perhaps a man of business, a lawyer – and the other is a man of some wealth.’

I turned to Holmes, pleased with my observations, but he was still gazing down through the window.

‘You might have observed,’ he chided, ‘that both are in mourning. Tell me, what do you make of the bags?’

‘The bags?’ I repeated, and looked again. The pair were now looking across to our building and, as I watched, they picked up their baggage and started across the deserted street.

‘The younger carries only a small Gladstone, while the elder carries a similar, though shabbier, bag and what seems to be a document case. I believe that confirms my earlier impression.’

‘I was referring,’ said Holmes, ‘to the bags at the knees of their trousers. I have remarked on other occasions that the hands are the most informative area when dealing with craftsmen, clerks and labourers, but that more may be learned from the trousers of the middle and upper classes. Here, as you rightly deduced, are a gentleman of position in expensive mourning clothes and his man of business in good office black, yet both have allowed their trousers to become distended at the knee. Can you not imagine a reason?’

I confessed that I could not and he drew out his watch.

‘The Great Western Express,’ he said, ‘arrived in London only minutes ago, yet we have two visitors who have taken the first cab on the Paddington rank and hurried straight to our doorstep without pausing for so much as a cup of tea.’

‘But what has that to do with their trousers?’ I asked, mystified. ‘And how can you say that they have travelled by the Western Express?’

‘Had they travelled overnight they would have occupied sleeping compartments. They have travelled early this morning, seated face to face in a carriage, and have leant forward to discuss at length some matter of great urgency, thereby causing the bags to which I drew your attention. They might have come from East Anglia, the Midlands or the South Coast, but the timing of their arrival indicates a fast cab from the Great Western terminus. If I shared your love of gambling Watson, I would wager you a sovereign that our bell is now being rung by the new Viscount Backwater and, I suspect, his solicitor.’

I had already learned not to doubt my friend’s extraordinary inferences and, within minutes, they were confirmed when Mrs Hudson announced Lord Backwater and his solicitor.

___

Author's notes on this chapter

Two

A CRYPTIC NOTE

‘Colonel Caddage’s views on my father’s death are completely erroneous!’ exclaimed Lord Backwater.

Our guests were seated and Mrs Hudson had replenished the coffee. The new Lord Backwater was evidently deeply agitated.

‘And who, pray, is Colonel Caddage?’ enquired Holmes.

‘He is our Chief Constable,’ said Mr Predge, the solicitor.

‘And he insists on treating my father’s murder as a casual act by poachers when it is evidently something else!’ asserted the young Lord.

Holmes raised a hand to stop the angry young man. ‘Perhaps it would be better if you were to give me the facts of your father’s death, Lord Backwater, without applying any interpretation. Then we shall see where they lead us.’

‘You are right, of course,’ said Lord Backwater and paused to collect his thoughts.

‘My father left our home on the afternoon before last at about four. He gave no indication that he would be absent from dinner but he had not returned by dinner-time. My sister and I grew alarmed and ordered a search for him. His body was found in the beech woods to the south of the house. He had been brutally beaten to death.’

Lord Backwater shuddered slightly and relapsed into silence. Holmes sat for a moment with his head tilted back and his eyes half closed without speaking.

‘The newspapers,’ he said, without opening his eyes, ‘give that account, but no more. Was your father in any way distressed or disturbed before he left the house?’

‘I did not see him that afternoon,’ said Lord Backwater, ‘but my sister reports that he was in good spirits and intended to walk no further than a particularly ancient beech tree. It was one of his favourite walks.’

‘The late Lord Backwater was celebrated for two things if one can believe the accounts in the newspapers,’ said Holmes. ‘He had given large sums to charity and he was notably reclusive. Is that so?’

‘He had donated hundreds of thousands to worthy causes,’ said the young man, ‘but he eschewed any form of notoriety. Almost his entire life was passed within the bounds of the estate. He hardly ever visited the county town and only went to London very occasionally on business matters.’

‘So that a stranger who wished to make a personal appeal to his charity might seek to waylay him on a familiar walk?’ queried Holmes.

‘Ha!’ exclaimed His Lordship. ‘Already you see another explanation.’

‘I see only what you tell me,’ said Holmes, ‘and I examine all the possible meanings of these data. Do not allow yourself to be misled by my questions, though you may rest assured that poachers are unlikely culprits.’

‘I was quite sure of that,’ said Lord Backwater.

‘I am certain. The time of day is wrong, the proximity to Backwater Hall is wrong, and because poachers would have fled or hidden rather than launch an unnecessary attack upon an elderly man. Do you have some other reason for your view?’ asked Holmes, and he opened his eyes wide.

The young man faltered slightly before my friend’s gaze. ‘I have... I have... a note which my father received.’

Mr Predge opened his document case and passed his client an envelope. Lord Backwater gave it to Holmes without opening it.

My friend turned the envelope over in his hands and I could see that it was of cheap white paper. Across the front a firm hand had written “Lord Backwater, Backwater Hall” in ink. It had been sealed but bore no postage stamp.

Holmes’ long fingers extracted a single sheet of paper from within the envelope and he held it up to the light.

‘A quarto sheet of cheap writing-paper,’ he mused. ‘No watermark, a poor pen-nib and a diluted ink.’

He lowered the paper and examined its message, which consisted of only a few words:

The man from the Gates of Hell will be at the old place at six.

There was no signature.

‘This was written,’ said Holmes, ‘by a man of moderate education and vigorous nature, probably in his middle years. The paper, pen and inks suggest a post office, hotel or inn, but if it had been written at a post office it would, most probably, have been stamped. Did your father have any Welsh connections?’

‘I do not think so,’ said Lord Backwater, but he looked to his solicitor for confirmation. The lawyer shook his head.

‘And does the expression “the Gates of Hell” mean anything to either of you?’ Holmes enquired.

Now they both shook their heads.

‘Then it may be the other Gates of Hell,’ said Holmes. ‘What about the phrase “the old place”?’

‘It means nothing to me,’ said Lord Backwater. ‘I have told you that my father frequently strolled to that particular ancient beech tree.’

‘When did your father receive this note?’ asked Holmes.

‘It seems to have been on the afternoon before his death,’ said the young man. ‘It lay on his desk that night and both my sister and I had been in the room during the morning and it was not there.’

‘Was anyone seen to call at the house in the afternoon?’

‘No, Mr Holmes, but I am not able to say that no one did.’

‘Then it is at least possible that it was delivered that day,’ said Holmes. ‘Why have you not given this to the police?’

‘But I showed it to Colonel Caddage!’ exclaimed Lord Backwater. ‘He told me that, since I could not explain it and since we could not swear to its delivery, it was irrelevant – a coincidence that undoubtedly had some innocent explanation!’

The lawyer nodded in confirmation. ‘It was at that point that I began to agree with Lord Backwater that a more vigorous investigation was required. A wire to my London agents gave me your name and we came at once,’ he said.

‘You were quite right,” said Holmes, ‘to consult someone who has always believed that there is a great deal too much coincidence about.

‘Lord Backwater,’ he continued, ‘the newspapers list some of the causes to which your father contributed over the years. Most were concerned with the education of the poor, the relief of poverty or the care of orphans. Did he contribute to animal charities?’

‘As you may imagine,’ said Mr Predge, ‘the late Lord Backwater received many appeals to his generosity. The causes you have mentioned were foremost, but he made regular donations to support organisations that cared for horses.’

‘He was not a dog lover?’ asked Holmes.

‘He neither liked nor disliked them. There are dogs about the estate,’ said Lord Backwater, ‘working dogs, and old Towler followed my father about.’

‘But neither old Towler nor any other dog was with him when he met his death?’

‘No sir,’ said the young Lord, and a slow light of remembrance dawned across his face.

‘What have you recalled?’ demanded my friend.

‘The dogs,’ said Lord Backwater slowly. ‘There have been a number of occasions recently when my father has ordered the dogs locked up before he went out for a walk, as he did that afternoon.’

Holmes smiled, but quickly suppressed the expression. ‘I fear,’ he said, ‘that I must ask a question that may appear indelicate in the circumstances. The newspapers say that Lady Backwater has been dead some ten years–”

‘Mr Holmes!’ interrupted Lord Backwater angrily. ‘Do not dare to suggest that my father went to meet a – a female! My father and mother were devoted to each other and since her death he has not looked at another woman.’

‘It was a remote possibility in the light of the note,’ said Holmes, ‘but it had to be considered. Now that it has been eliminated, we may, I think, draw some inferences.’

Lord Backwater and Mr Predge leaned forward eagerly.

‘It seems likely that the note was, in fact, delivered by hand to Backwater Hall on the afternoon of your father’s death,’ said Holmes. ‘The fact that no one saw it delivered is not evidence against the proposition. That an action was unremarked does not make it impossible. The note seems to be from someone with a long-standing acquaintance with your father, if not friendship.’

‘Why do you say so?’ asked Lord Backwater.

‘Because your father accepted the assignation in the note and went to it without trepidation and with no precautions. Evidently he felt that he had nothing to fear from the meeting.’

‘Then he was killed by someone that he knew!’ exclaimed the young Viscount.

‘I did not say so, nor do I believe it to be so,’ said Holmes. ‘You are in danger, Lord Backwater, of running ahead of the available data. Tell me, had your father any enemies?’

‘None of which I was aware,’ said the young man, and turned again to his lawyer for confirmation.

‘The late Lord Backwater,’ said the solicitor, ‘was universally admired and respected. Apart from those major acts of charity which became known to the public, he made many minor donations to relieve distress in individual cases in the area of Backwater Hall. In addition, he was scrupulous in his commercial transactions, often to his own disadvantage.’

Holmes nodded. ‘I see,’ he said. ‘Then there is only one more question of consequence. What connection had Lord Backwater with the Antipodes?’

Lord Backwater and his solicitor looked at each other with identical expressions of astonishment. Even I, who had become used, I thought, to my friend’s apparent non-sequiturs, was bewildered.

‘None, none, I think,’ said the young Lord. ‘He had business interests, of course, in many regions – in America, in Canada, in South America, South Africa – but you will have read that in the obituaries. I do not think he had any interest in the Antipodes, had he, Mr Predge?’

‘I am sure not,’ said the lawyer. ‘His fortune came from the mining of metals and gems and, as Lord Patrick has said, his holdings were widespread, but I cannot recall any connection with Australia or New Zealand.’

‘You said that you had only that one question,’ said Lord Backwater. ‘Does that mean that you have reached a conclusion, Mr Holmes?’

‘I understand your concern to bring your father’s murderers to justice,’ said Holmes, ‘but it is far too early for conclusions. Inferences, yes. We can be reasonably sure that your father left home in a cheerful frame of mind to meet an acquaintance – perhaps even a friend – who disliked or was afraid of dogs and whom your father did not regard as a threat. In keeping that rendezvous he was set upon and savagely killed.’

‘Then you believe his friend – his acquaintance – lured him into a trap?’ asked Lord Backwater.

‘I do not know,’ said Holmes. ‘At this point I cannot be certain, but I believe it improbable. It seems to me much more likely that the trap was set by others, for one or both of them. No doubt we shall learn more when we accompany you to Backwater Hall.’

He rose and our guests rose too. ‘When shall you be there?’ asked Lord Backwater.

Holmes glanced at the mantel clock. ‘I have no engagements that require me to remain in town,’ he said. ‘If Mr Predge will be kind enough to reserve a first-class smoker, Watson and I will meet you at Paddington in time for the noon train. Good day, Lord Backwater. Good day, Mr Predge.’

When the visitors had departed, Holmes flung himself full length on the couch with a hand over his eyes. ‘Be so good,’ he asked me, ‘as to run over the longest obituary you can find for me.’

I shuffled through the mass of the morning’s papers and finally selected a lengthy obituary of the late Viscount Backwater and rehearsed the principal points for Holmes.

‘Former James Lisle – born in humble circumstances – orphaned at an early age – took to the sea – adventurous years in America – one of the discoverers of the Great Empress Silver Lode – expanding interests in mining – returned to England twenty-five years ago – reclusive life at Backwater – increasing generosity to charities – made Viscount Backwater – married Lady Felicia Eaglestone – wife dead ten years – leaves a son Patrick, the new Viscount, and daughter Patricia, engaged to Henry Ruthen.’ I looked up at Holmes. ‘There seems to be little else of consequence,’ I said.

Holmes waved his hand impatiently. ‘It is not there, it is not there!’ he exclaimed.

‘What is it you are seeking?’ I asked.

‘The Antipodean connection,’ he snapped.

‘It is the entry to this maze and we must find it.’

‘But why are you so certain that there is such a connection?’ I enquired.

‘Because it is in the note,’ he replied, and swung his long legs off the couch. ‘Be so good as to ring for our boots, Watson. We have an appointment at Paddington.’

Three

THE TATTOOED CORPSE

Our journey to the west was pursued largely in silence. Both Lord Backwater and his lawyer were showing signs of the strain under which the tragedy and their hurried journey to London had placed them and it was impossible for me to question Holmes as to his remarks at Baker Street.

Wiggin, Lord Backwater’s principal gamekeeper, met us at Backwater Halt with a carriage, but also present was an Inspector of Police who greeted Holmes warmly.

‘Mr Holmes,’ he said, ‘when I heard that Lord Backwater had gone to consult you I was very pleased, sir, very pleased indeed.’ I was intrigued to note that the accent was from the lowlands of Scotland rather than these western valleys.

‘Scott!’ exclaimed Holmes, smiling warmly. ‘The move west has evidently been successful.’ He turned to me and introduced the officer. ‘Watson,’ he said, ‘this high official of the County Police was a mere constable back in my Montague Street days, when I had the opportunity to assist his division with a small matter. I take it,’ he said to the Inspector, ‘that you are not in agreement with your Chief Constable’s view of the matter?’

‘That is not for me to say, sir. Let us just say that I am pleased to see you here, Mr Holmes.’

Holmes turned to our client. ‘I shall ask Inspector Scott to take Dr Watson and me to the scene of the crime, Lord Backwater, but there is no need for you to attend. Perhaps we may wait on you at Backwater Hall later, when I may have some observations for you.’

The Viscount’s relief was evident. ‘That is most thoughtful of you, Mr Holmes. We shall take your luggage on and await your findings.’

Very shortly Wiggin took Lord Backwater and his solicitor away and Holmes turned to Inspector Scott.

‘Now,’ he said, ‘we may address ourselves to that most unpleasant but necessary of speculations, Inspector. Is there any likelihood that Lord Patrick, or any other member of the family, is involved in this matter?’

‘I should say not,’ said the Inspector. ‘Not that it can be entirely ruled out, but as far as I can determine relations between the family were most amicable.’

‘Then, if you do not have violent poachers in these parts, we had best find another explanation,’ said Holmes. ‘Is it possible to see the body?’

‘It is, Mr Holmes,’ said Scott. ‘It is at the county mortuary for the present. The Chief Constable was all for releasing it to the family, but once I heard you were on your way I knew you would wish to examine it.’

The station trap took us to the little red-brick county mortuary buildings where we were soon examining the corpse of a well-built, healthy man in his fifties. His early days had left him with fine muscular development and he had not run to fat in his retirement.

The front upper portion of the body and both arms were covered with the marks of vicious cudgel blows, while the cause of death was easy to see in a single, massive blow struck to the back of the head. It was plain that Lord Backwater had defended himself vigorously against more than one assailant before being felled from behind.

Inspector Scott and the attendant rolled the body into a prone position and, as the back was revealed, Holmes drew a long breath and smiled slightly as though some unspoken prediction had proved true.

I was astonished, for the pallor of death had made more visible on the dead man’s back a pattern of old and wide scars.

‘He was flogged!’ I exclaimed. ‘More than once by the look of it!’

‘So I perceive,’ said Holmes, ‘but can your military eye help me as to whether this was done in the Army or Navy?’

‘No,’ I said, after a second look. ‘I’ve seen any number of old sweats who’ve been triangled. Their marks are higher than these, care being taken in the services to avoid the kidneys. This man was lashed at random by someone, most probably in his youth.’

‘Excellent, Watson,’ said Holmes and signalled to have the cadaver restored to its former position. ‘Now, what do you make of his tattoos?’

‘Very little,’ I replied. ‘We know that he was humbly raised and worked in mines. Many such men carry tattoos.’

‘Not such as these,’ said my friend, and stepping back towards the table he turned the corpse’s left forearm slightly outwards.

I had noted that there was a tattoo on the inner side of the forearm, but I had paid it scant attention during my examination. Now I looked more closely and saw that it was amateur work of the kind that is done by schoolboys with a pen-nib and ink, or by soldiers with a knife-point and gunpowder, but it had been strongly and regularly incised and stood out clearly against the pallor of the skin.

It was none of the patterns that I had ever seen in the Army or in my civilian practice. It consisted of a heraldic cross-pattée with a single word in capitals across its centre – “NEVER”.

My face must have shown my bewilderment, for Holmes turned the right forearm as well. There, in the matching position, was another such decoration, this time a simple square containing the word ‘EVER’.

‘Do they tell you anything?’ Holmes demanded.

‘Very little, Holmes,’ I admitted. ‘They are not professional work, but that means little. Soldiers, sailors, even public schoolboys tattoo themselves and each other.’

‘Schoolboy tattoos are made with common ink,’ said Holmes, ‘while soldiers and sailors use gunpowder. Both fade relatively quickly. Sometimes lampblack is used and that can last a lifetime. I think that is the agent here.’

He turned the two forearms again, gazing thoughtfully at the inscriptions.

‘It is a pity,’ he remarked, ‘that they are not on the torso or the upper arm.’

‘Why so?’ I enquired.

‘The growth of the body and the development of the muscles would have distorted them had they been applied at an early age, but no such distortion occurs on the inner forearm. What do you learn from the symbols themselves?’

‘I have seen a deal of tattoos,’ I said, ‘but I recall none like these. Soldiers have swords, guns, regimental emblems; sailors have the anchor of faith and the crown of hope, ships, ships’ names, mermaids; both have hearts, flags, inscriptions to sweethearts, wives and mothers. I even remember attending a fellow on the Orontes who had the famous fox-chase tattoo.’

‘Well done, Watson!’ exclaimed Holmes. ‘I see that you have retained a little of my oft-repeated observations on the importance of tattoos. Professor Lombroso asserts that all tattoos are the hallmark of a criminal personality, but in that, as in so many other matters, he is wrong. Continental criminals may have misled him by their flamboyant tattoos. British criminals occasionally wear a small emblem of their particular gang, often on the edge of the left palm, where it is unobtrusive and readily covered by the thumb, and a very few wear emblems of their criminous trade, but in general they conform to the ordinary decorations of the lower classes.’

‘Then what do these mean?’ I asked, indicating Lord Backwater’s tattoos.

‘They mean’, he said, lifting each arm in turn, ‘on the cross – never, and on the square – ever.’

‘An expression of affection and loyalty,’ I said. ‘Surely the name of a sweetheart should be with them?’

Holmes chuckled mirthlessly. ‘There is little affection embodied in that oath,’ he said, ‘and it was directed to no female.’

‘A secret society?’ I hazarded. ‘Do they signify that Lord Backwater was a criminal?’