Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Remote Verlag

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

A masterclass in manipulation from the bestselling communication coach Nice is for suckers. Want to win in today's world? Put yourself first and start getting your own way. Want to seem confident but haven't got a clue? Want to prove yourself right using whatever facts you like? This essential book will teach you how to run rings round your acquaintances, family members, and colleagues. It's crafty, provocative, and best of all, guaranteed to work. Here's what you need to know: Rule 1: Know who you're up against. Rule 2: Know all the dirtiest tricks. Rule 3: Manipulate others before they manipulate you! International phenomenon Wladislaw Jachtchenko is here to show you how. This international best-selling communication coach opens up his box of tricks to show you how to use bogus arguments, devious body language techniques and twisted truths to get the last word in every single conversation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 304

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

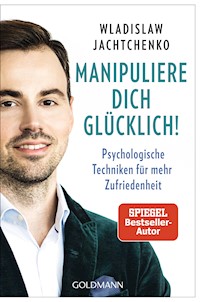

The Manipulation Bible

The Dark Side of Communication

WLADISLAW JACHTCHENKO

www.remote-verlag.de

© 2022 Wladislaw Jachtchenko

This work is protected by copyright. Any use requires the exclusive consent of the author.

This applies in particular to reproduction, utilization, translation, and storage of the work and processing in electronic systems.

For questions and comments:

Originally published as Dunkle Rhetorik, Goldmann Verlag, 2019

© Wladislaw Jachtchenko, 2019English translation © George Robarts, 2021

First edition 2022 Remote Life LLC, Powerline Rd, Suite 301-C, 33309 Fort Lauderdale, Fl., USA

Cover design: nskvsky

Editorial Team: Maximilian Mika

Book layout: Melvyn Paulino

ISBN Print: 978-1-955655-30-9

eISBN: 978-1-955655-29-3

For more information about the publisher, please visit: www.remote-verlag.de

About the Book

Do you want to have the final say in arguments?

Do you want to shut down your arrogant colleagues?

Do you want to prove that you were right all along?

Bestselling author, communication coach and public speaker Wladislaw Jachtchenko is here to help. This book is a treasure trove of tips and tricks for honing your communication skills – teaching you to manipulate your way through everyday scenarios, and finally start getting what you want.

About the Author

Wladislaw Jachtchenko studied political science, law, history and literature in Munich and New York. He worked in a legal firm in Munich and as a research associate at the United Nations in New York, before following his passion to begin work as a communication coach and public speaker in 2007. He is the founder of the Argumentorik Academy (https://argumentorik.com/en/) in Germany, where he leads training courses in interpersonal communication and business negotiation. He has enjoyed considerable success at international debating tournaments, ranking among the Top 10 Speakers in Europe, and has won multiple awards for his work. With his online courses alone he reaches and teaches over 200,000 learners across the globe.

About the Translator

George Robarts studied German and Italian at New College, Oxford, where he specialized in prose and verse translation, graduating with first-class honors. He won Third Prize in the prestigious Geisteswissenschaften International Non-Fiction Translation Competition in 2020, awarded by the German Publishers’ and Booksellers’ Association.

Contents

Foreword: Being Nice is So Yesterday

Introduction: You Manipulate People Daily

The Top 10 Skills for Everyday Manipulation

1. Seeming Confident When You Haven’t Got a Clue

2. Dazzling People with Your Appearance

3. Building a Quick Rapport

4. Telling the Perfect Lie

5. Forcing People into Agreement

6. Steering the Conversation with Questions

7. Overwhelming People with Emotions

8. Attacking the Content – and Disarming the Mind

9. Attacking the Person – and Leaving Them Speechless

10. Shutting Down Disagreeable Conversations

The Three Boxes of Dirty Communication Tricks

I. First Box of Tricks: Cognitive Biases

1. Superiority Bias

2. Confirmation Bias

3. Attentional Bias

4. Cognitive Dissonance

5. The Priming Effect

6. The Anchoring Effect

7. Social Proof

8. Optimism Bias and Wishful Thinking

9. Processing Fluency

10. The Halo Effect

11. Authority Bias

12. The Sunk Cost Fallacy

13. The Reciprocity Trap

14. The Scarcity Trap

II. Second Box of Tricks: Verbal Tricks

1. Technical Terms and Foreign Words

2. Weak Language and Power Talking

3. Framing

4. Metaphors

5. Loaded Language

6. The Word “Because”

7. The Voice and Its Nuances

8. Quotations

9. The Passive

10. Ten Little Verbal Tricks

III. Third Box of Tricks: Bogus Arguments

1. The Irrelevance Technique

2. The Appeal to Tradition

3. The Personal Attack

4. The Circular Argument

5. The Slippery Slope

6. The Appeal to Common Sense

7. The Appeal to Emotion

8. The Endless Repetition

9. The Faulty Generalization

10. The Cum Hoc Fallacy

11. The Post Hoc Fallacy

12. The Argument from Utility

13. The Argument from Fallacy

The (Im-)Morality of Manipulation

What is Morality?

The Moral Stages of Manipulation

Conclusion: Manipulate Anyone, Anytime, Anywhere

Notes

Foreword:Being Nice is So Yesterday

Any person who tries to be good all the timewill fall to pieces among so many who are not good.

Machiavelli

The good guys of this world often come up short, because the bad guys outsmart them with nasty, manipulative tricks. But enough is enough! It’s time to take the gloves off, wave goodbye to good manners, and finally start getting our own way. Almost everyone around us is trying to manipulate us, consciously or not – so from now on, this is rule number one:

Manipulate others before they manipulate you!

One thing is clear: to be successful in our dog-eat-dog society, you don’t have to be competent. You only have to seem competent and know how to influence those around you.

And we don’t need to look as far as politicians, the undisputed champions of alternative facts and personal insults, to see this in action. Our own everyday lives are saturated with spiteful remarks, backhanded compliments, power struggles, killer phrases – and only the savvy will survive!

This unholy bible of tips and tricks will equip you with all the communicative tools you need to get ahead. You will learn to hold your ground in a world full of manipulators; to put your own wishes first; and to assert your own ego – in your personal as well as your professional life.

The introduction reveals why you are a born manipulator. You will then discover the Top 10 Skills for Everyday Manipulation. These are crucial skills that you need at your fingertips if you are to succeed in our manipulative world. Next, I will open up The Three Boxes of Dirty Communication Tricks. These shed light on the subtleties of manipulation. The Trick Boxes are designed to supplement your Top 10 Skills – enabling you to manipulate others with nuance and precision, and equipping you with a wide selection of tools to draw on whenever you need. Last but not least, I will take a closer look at the morals of manipulation, and where the limits are.

You do not necessarily have to read this book in sequential order. If you like, jump straight in to the chapter that intrigues you most.

Enough preamble. Let’s get started!

Introduction:You Manipulate People Daily

If you act like a worm,don’t complain when you get squashed.

Immanuel Kant

You have been manipulating people since you were born. Every single day. And other people have been manipulating you too. Every single day. The question is: who’s better at it? Who gets their own way in the end? And who gets trampled on?

You probably won’t believe me when I say that you are a born manipulator. Since you took your first breath, you’ve been manipulating people constantly to get your own way – and you will continue to do so to the end. Don’t buy it? Well, here are just a few examples from our everyday lives:

•As babies we cry until we get enough food, drink, and attention from our parents. And if they don’t respond to our cries, we scream even louder – until they give in and satisfy our needs.

•As toddlers we throw tantrums by the shelf at the supermarket checkout, wailing and whining until our pester power gets us what we want. And as Christmas approaches, we put on our best behavior, in the hope of finding our dream present under the tree.

•As schoolchildren we cheat in tests, fake headaches before important exams, and feed our teachers elaborate lies about why we haven’t done our homework.

•As teenagers we try to impress our crushes by looking cool and wearing trendy clothes.

•As first-time job applicants we pad out our CVs and present ourselves at interview as “highly motivated, reliable team players” – but by the end of the day we’re usually counting down the minutes until it’s time to go home.

•As colleagues we make an extra-special effort to be nice when we need something from another colleague.

•As parents we drop our children off at grandma’s so we can finally have some peace and quiet – but we tell our kids that grandma has been missing them terribly and that’s why they’re going to stay with her.

•As bosses we massage our employees’ egos with phrases like, “You’re the only one I can trust with a task as important as this!” – because how can they then refuse?

•As grandparents we spoil our grandchildren rotten to guilt-trip them into visiting us more often.

The list could go on for ever. Our many roles in daily life all involve manipulating people – so it’s a mistake to associate manipulation only with politicians, insurance brokers and car salesmen. We are all at least as manipulative in our everyday lives as this little selection. Some more so, some less so. Sometimes we manipulate others consciously, often we do it unconsciously. Sometimes it works well, other times less well. But every single one of us does it. Every single day.

Interestingly, we’re most vulnerable to people we wouldn’t expect to manipulate us: family, friends and acquaintances. It goes without saying that friendly colleagues, bosses and business partners also have plenty of nasty tricks up their sleeve. We’re all merrily manipulating each other!

So, the question is not if we manipulate others, but how effectively we do it. And whether we can get our own way in the end. One thing is certain: if you know the tricks of the trade, you hold all the cards. And if you don’t, you’ll be left with nothing!

The Big Question: Is Manipulation Immoral?

Isn’t it morally reprehensible to manipulate other people? Most people – and most authors – would answer with a resounding “Yes! Manipulation is immoral! You should only use techniques like that in self-defense – if at all!”

But it’s not as simple as that. First off, we need to clarify what manipulation actually means. The following definition should suffice for our purposes:

Manipulation means covertly influencing another person for your own benefit.

Manipulating someone is not to be confused with persuading them (openly influencing them for credible reasons) or talking them round (openly influencing them through sheer persistence).

Most people consider persuasion the best (i.e. the most honest and rational) way of influencing someone. To many people, the idea of talking someone round sounds unreasonable and pushy, and generally carries negative connotations. It means that someone will end up doing something that they originally didn’t want to do. Still, though, the process of talking someone round is at least relatively transparent: it’s hard to miss when someone won’t stop pestering you about something.

Of the three, though, manipulation enjoys the worst reputation by far. Unfairly so, I reckon – and I’ll tell you why.

The most frequently cited reason why manipulation is immoral is that it is usually a covert operation. In other words, it means exploiting the ignorance of a defenseless, unsuspecting “victim” – and catching them out with a devious trick.

But just because something happens covertly – without another person’s knowledge – this does not necessarily make it immoral. If I extinguish a small fire on my neighbors’ front lawn while they’re out, and they don’t know a thing about it, you can hardly condemn me for it, can you?

And even if you’re only acting in your own interests, that does not automatically make your behavior immoral either. Either my actions could have no effect at all on the other person (Scenario 1: I benefit, and no-one else gains or loses anything) – or we might both gain from it (Scenario 2: I benefit, and someone else also benefits without noticing that they’ve been manipulated).

Manipulation only becomes immoral when you act in your own interests without concern or consideration for other people, and end up harming them. What matters is how and why you manipulate people. We should also consider whether, in some circumstances, immoral actions can be justifiable. And if so, where do we draw the line? (For a closer look at this, turn to p. 193 for a systematic overview of the morality of manipulation, with accompanying explanations.)

What’s the Easiest Way to Manipulate People?

There is no single most effective manipulation technique. It’s more a case of different people being manipulable by different methods. Some are fooled by professional body language; others are susceptible to arguments appealing to their sympathy; others are reeled in by “alternative facts” or compliments – and so on.

Good manipulators will look for their opponent’s Achilles’ heel and swiftly locate this weak spot. And as we know, everybody has a weak spot. You just have to find it.

The key thing to remember is that when people’s interests are in play, every interaction turns into a game of communicative chess. And there are always opportunities to checkmate your opponent.

You might protest, “But I don’t want to manipulate anyone! I’d rather just use my powers of reasoning.” Two thoughts on that:

First, arguments generally follow the pattern of a fistfight. The German philosopher Jürgen Habermas means it when he talks of the “unforced force of the better argument”. But people don’t like being forced – and in an argument, they’ll instinctively take the opposite side from you most of the time. To look at it another way: in Schopenhauerian terms, our innate vanity makes us especially protective of our own intellect – so during arguments, we simply do not want our opponents to be right. That’s why verbal spats very rarely end with one person saying, “Actually, you’re right!” In most cases they end in a stalemate, with neither side wanting to concede. The rewards of manipulation are much greater, since your opponent won’t even notice your skillful maneuvers. And because they won’t realize you’re wrapping them around your little finger, they won’t have their wits about them.

Second, manipulation has the advantage of being easy to use. In an argument, you are always at risk of making mistakes: starting from false premises, using flawed definitions, or drawing the wrong conclusions. And the longer the argument goes on, the more targets you give your opponent to aim at. That’s why presidents and prime ministers around the world usually settle for short statements – rather than long chains of reasoning.

Manipulative tricks, by contrast, are instantly effective, easy to learn – and manipulators move in the dark, offering them additional protection from attack. So manipulation comfortably beats reasoning, two-nil.

THE TOP 10 SKILLS FOR EVERYDAY MANIPULATION

Rhetoric is more honest,because it acknowledges deception as its aim.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Given that (if we’re honest) we are all constantly manipulating and misleading each other, the only sensible way forward is for us to master the art. In the following chapters, you will learn the ten most important skills you need at your fingertips in order to get your own way every day – in both your personal and professional life.

The Top 10 Skills

1.Seeming Confident When You Haven’t Got a Clue (p. 11)

2.Dazzling People with Your Appearance (p. 17)

3.Building a Quick Rapport (p. 22)

4.Telling the Perfect Lie (p. 27)

5.Forcing People into Agreement (p. 32)

6.Steering the Conversation with Questions (p. 38)

7.Overwhelming People with Emotions (p. 44)

8.Attacking the Content – and Disarming the Mind (p. 49)

9.Attacking the Person – and Leaving Them Speechless (p. 56)

10.Shutting Down Disagreeable Conversations (p. 60)

Even if you still don’t believe that you ever manipulate your fellow human beings, learning about these Top 10 Skills remains an absolute must – so that you can instantly recognize when someone is trying to manipulate you, and avoid falling for their tricks.

1. Seeming Confident When You Haven’t Got a Clue

Knowledge is power.No knowledge? No matter!

Anonymous

We live in a knowledge-based society. Those in the know are rewarded. Those who know nothing are punished – with bad marks at school, or with less chance of a promotion at work.

Of course, knowledge isn’t the only factor in success, but it is undoubtedly a crucial one. And your outwardly nice but inwardly resentful colleague is just waiting for the opportunity to gleefully cut you down. Even if it’s already obvious how little you know about the issue at hand.

Most people are afraid of being embarrassed and exposed. Human beings are stubborn, and we do our best to avoid awkward scenarios like this. The solution is to seem confident even when you haven’t got a clue. It sounds tricky, but it’s just another learnable skill. A very specific competency. To be precise, it is an incompetence-compensating competency: an ability to gloss over what you don’t know by competently deploying specific techniques. Simply put, it’s the ability to hide your lack of knowledge.

As with everything in life, if you know the tricks, you can quickly take control of any situation. Before I present you with my seven most stylish techniques, here’s a tip: whatever you have to say, professional body language and tone of voice will instantly make you look far more competent. Amateurs will break eye contact mid-conversation if there’s something they don’t know. They will hesitate before answering, and then speak too quickly – their flustered appearance revealing at a non-verbal level that have no idea what they’re talking about.

Seasoned tricksters do things differently. Even if they don’t know the first thing about the matter at hand, they always have their body language under full control. Most importantly, they will:

•maintain eye contact with the other person

•make active gestures as they speak

•stand up straight, directly facing the other person.

But confident body language isn’t all. They will also take pains to ensure that their voice sounds convincing. They will always speak:

•loudly and clearly

•on the slow side if anything – never too quickly

•with deliberate pauses

•without ever getting mixed up.

Professional body language and tone of voice are the absolute fundamentals of seeming confident when you haven’t got a clue. If you don’t have these at your command, you should start practicing them at once.

For now, let’s take a closer look at my seven favorite tricks.

Trick 1: Abstraction

When you can’t come up with an adequate factual answer to a question, one inconspicuous technique to make you sound smarter than you are is abstraction.

Imagine that someone asks you out of the blue, “What are your thoughts on the Bologna reform?” And let’s assume that you don’t know that they’re talking about the 1999 agreement to align courses of study across Europe (with the introduction of the Bachelor’s / Master’s system and ECTS [European Credit Transfer System] points).

The trick is to answer this concrete question in abstract terms. You can avoid saying anything specific about the Bologna reform, and instead comment on the notion of “reforms” in general. You might say something along the lines of, “On the whole, political reforms can only really be judged by those affected. It’s no good asking the politicians – they’ll just keep defending their own decisions. And the people affected by this reform are divided on it. But I find top-down reforms in politics generally pretty questionable.”

You haven’t said anything about the Bologna reform – but it still sounded smart.1

Or perhaps someone asks you, “Do you like Schoenberg’s twelve-tone music?” Let’s assume that you don’t have the foggiest idea about the twelve-tone technique and the Second Viennese School either. What do you do? The solution, once again, is not to offer any concrete response to the question, but to talk more generally about music and our appreciation of it.

So you could reply, “Different people have different tastes. It’s just a matter of preference whether you like one type of music or another. Personally, I’m more into jazz fusion.”

You’ve said nothing in response to the actual question, but have come up with universal truths that cannot be attacked. The trick with abstraction is to seize on a familiar term in the question, and elaborate on it by spouting a few generalities.

Trick 2: Digression

A subtle trick that politicians use constantly is gradual digression from the original question towards a subject that they’re more comfortable with.

Let’s revisit our first example. Someone asks you, “What are your thoughts on the Bologna reform?” – and let’s assume that you still don’t know a thing about it. How can you skillfully steer the conversation in a different direction? Easy: you parry the question. “I think it’s less important right now than…” – and then you start talking about something else entirely.

For instance, you could reply, “People get very hung up on reforms, but I think the really important issue right now is how politics constantly favors the rich.” Of course, if you don’t fancy starting a fiery argument about wealth redistribution, you can pick another more trivial topic, if one comes to mind. Depending on the situation, you could move on to something more personal. It’s astonishing how many people seem not to notice this maneuver. Even if they do, they generally choose to let it go.

If you know the other person well enough, you should pick a new subject that they can relate to. Let’s say you have a mutual friend called Steffi, who is a great friend of theirs. You could simply say, “What I really wanted to talk about is how Steffi is! I haven’t seen her for ages.”

This verbal maneuver away from a particular topic is also known as a “red herring” – a term dating back to the 19th century, or possibly earlier. Fugitives supposedly planted the strong-smelling smoked fish to throw tracking dogs off the scent. So if someone tries to take your conversation down a completely new avenue, you can counter, “What sort of red herring is that?” You’ll immediately break their stride.

Trick 3: Deflection

A slightly more aggressive version of digression is point-blank deflection. This is a way of fending off uncomfortable questions and statements. If someone asks you a question – “What do you think this department can do better?” – and nothing occurs to you, you can shoot back, “That’s not the question we should be asking. This isn’t about what our department could do better, but what better decisions management could have made!”

This trick sounds similar to digression. The aim here, though, is not to divert the conversation away from one topic towards another – but to shift the whole discussion from a factual level to an emotional one.

Schoolteachers and professional coaches have always taught us to stick to the facts. But if we want to distract someone from the gaps in our knowledge, invoking strong emotions will usually do the trick. The best bluffers will indignantly clamor, “That’s totally the wrong question to be asking!” Suddenly, the other person is on the back foot – and you have the upper hand again.

Trick 4: Agreement and Approval

Another cunning way of hiding your own ignorance is to agree with and approve of whatever the other person says. People are susceptible to flattery: gratification clouds their judgment, and they forget that we haven’t actually contributed anything to the conversation.

Phrases like, “That’s a really insightful explanation!” and “Interesting argument! I never thought about it like that before,” will give the other person wings. Your approval will encourage them to expostulate further on the subject – and they’ll keep talking the whole time.

If they eventually do ask our opinion, we can heartily agree with them – and immediately steer the conversation into more familiar territory.

Trick 5: Attribution

One of the easiest tricks in the book is to make any old claim and attribute it to someone else, like so: “I recently read in the New York Times that…” This ruse has two immediate advantages for us. First, it implies how well read we are. Second, it takes us out of the firing line – because the argument we are making is not our own. So even if the other person knows much more on the subject and rebuts our fictitious assertion, it only proves their intelligence and lets them feel good about themselves – without making us look bad.

Trick 6: Counter-Questions

When you’re stuck for ideas, you can express confidence by turning the tables on the questioner. The simplest counter-question is, “What do you think?” Only rarely will they suspect your ignorance – unless you use this technique multiple times in quick succession.

Most people like the sound of their own voice, and prefer talking to listening. I’ve lost count of the conversations I’ve had in which my active contribution has felt like less than twenty percent of the discussion – and at the end the other person beams, “It was great to meet you! I’m so glad that we got to chat!”

A slightly more aggressive version of this tactic is to question the other person’s motivations. You fire back, “Why do you want to know that?” or “Why are you asking me that?”

You’re insinuating that your opposite number has an ulterior motive. They’ll usually respond by defending themselves – and in doing so, they will divulge information on the issue at hand, which you can utilize in reply.

Trick 7: Playing the Philosopher

An easy way of sounding intelligent is to pretend to be skeptical of everything and – without going into specifics – point out that opinion is split on a particular topic. You can add some spice with a choice quotation, if one occurs to you.

Let’s suppose that someone is curious to know whether you think drugs should be legalized, and asks your opinion. You don’t know the first thing about drugs, but you want to say something smart. You could reply, “I’m fairly skeptical. Different studies draw different conclusions – and ultimately I don’t believe any statistics that I haven’t made up myself.” Then, ideally, you give them a slightly smug grin.

Borrow this response word for word, if you like – it works ninety-nine percent of the time. Or you can make up a phrase of your own. The important thing is to make your statements so general that they don’t offer any new lines of attack.

So there we have it – my seven top tips on how to seem confident when you haven’t got a clue. From now on, you’ll never be tongue-tied, even if you have no idea what you’re talking about. You’ll be able to reel people in, even if you have nothing to say.

The next chapter reveals how to use your appearance to achieve the same effect.

2. Dazzling People with Your Appearance

Body language is worth 55 percent.Tone of voice is worth 38 percent.Content is only worth 7 percent.

The Mehrabian Myth

How important is your appearance? Communication experts across the globe would direct you towards the American psychologist Albert Mehrabian and his two studies from the 1960s.2 You might have seen the headline statistics before: the studies claim that content only counts for 7 percent, while tone of voice and body language allegedly make up 93 percent. If this is true, we should all immediately start taking drama lessons to perfect our use of gesture, facial expression, and intonation. As for facts and reason – forget it. The “post-truth” Trump era sends its regards.

Is Content Really Only Worth Seven Percent?

When Mehrabian is asked about his conclusions (which isn’t a rare occurrence) he usually shrugs and says that anyone with any sense can see that content can’t possibly only be worth 7 percent. He illustrates this with an elegant example: “If I were to tell you that the pencil you are looking for is upstairs in the desk drawer of the bedroom, three drawers down, I couldn’t do that nonverbally… But I could do that very precisely with words.”3 Tone of voice in particular would be very little help.

Similarly, if content really were only worth 7 percent, then I’d be able to understand 93 percent of what Chinese or Japanese people were trying to tell me, without speaking a word of either language.

Nonetheless, what Mehrabian actually discovered in these two experiments is still vital for aspiring manipulators: as soon as gesture or intonation begin to contradict content, people will believe your body language and tone of voice, rather than your actual words. In other words, the 55-38-7 rule is not true by default, but comes into play when there is a mismatch between verbal and nonverbal or paraverbal levels of communication.

We have known this instinctively for a long time. If someone looks at their feet and tells you in a monotone that they’re feeling fantastic, you’re unlikely to believe them. Or if they gloomily murmur that yesterday’s party was “great”, you’ll have your doubts. We automatically detect contradictions between what someone says and their body language or tone of voice – and we ascribe greater importance to the latter two factors, probably because they are involuntary – i.e. genuine and honest – responses.

Note: To come across as credible, your body language, tone of voice and content must be free of contradiction (consistent).

So, does this mean that body language and tone of voice are less important than the literal meaning of your words? Of course not! That said, you can use your appearance to reel people in by exploiting the astonishingly powerful “Halo Effect”.

The Deceptive Halo Effect

The halo effect is a cognitive bias – a sociopsychological phenomenon in which one striking positive quality, such as attractiveness, outshines the rest of a person’s character traits, so that we see them through rose-tinted spectacles and make a positive overall judgment of them.4 A typical example of the halo effect is a teacher objectively overestimating a conventionally pretty student’s aptitude in a certain subject. The same applies to a tall, manly and handsome soldier, whose attractiveness will mislead his superiors into overestimating his accomplishments against those of his average-looking comrades.5 Even the question of how competent politicians look alongside fellow campaigners – and who consequently comes out on top in the next election – is substantially affected by appearance.6

The astonishing thing is that this “halo” does not have to be seen first-hand. It’s enough to have a “manipulated reputation”. In the Rosenthal Experiment,7now famous in academic circles, teachers were told that certain pupils of theirs were exceptionally gifted. In reality, these “gifted” students had been selected at random. But the teachers proceeded unwittingly to give more encouragement to the supposed “intellectual bloomers” than the rest of their pupils: they were given more praise, allowed more time to answer, and received more individual support. Intriguingly, the IQ of these pseudo-gifted students disproportionately increased over time relative to the “normal” pupils. And as for the pupils’ character, the “bloomers” received particularly dazzling reports.

Our reputation and attractiveness have a defining impact on people’s estimation of our intelligence and persuasive powers. This may seem unfair. But savvy manipulators have long been using this to their advantage – ensuring that they always look as good as possible, and curating an impeccable reputation.

Confident Body Language and Assured Tone of Voice

Prestige and looks aren’t everything, though. People are also considered more credible if they consistently maintain eye contact and speak in an assured tone of voice – regardless of what they are saying. An experiment in a courtroom demonstrated that witnesses who looked the cross-examiner in the eye and didn’t look away while speaking were consistently perceived as more credible.8

Another experiment focused on the effect of tone of voice on the speaker’s credibility. Subjects listened to two witnesses. The first spoke fluently and assuredly – the second hesitated and stammered. As you can imagine, the subjects considered the one with the steadier voice significantly more honest and competent.9

One of the most famous examples of the crucial importance of body language and tone of voice is the first TV debate in history, back in 1960, between US presidential candidates John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Kennedy looked better, spoke to camera more often, his suit fit him better, his body language was more relaxed – and as a result, he won more viewers’ votes than his opponent.

But here’s the twist: people who followed the debate not on TV, but on the radio, claimed that Nixon was the clear winner. How could that be?

The radio audience couldn’t see Kennedy’s cool body language. And Nixon had clear vocal advantages. The pitch of his voice was deeper, and he spoke more slowly, exuding more authority. Kennedy’s voice was higher, and he tended to speak more quickly, so he came across as less sure of himself.

This shows why, in an ideal world, you should work on refining both your body language and your voice.

Can you believe it? The candidate with the better body language wins on TV – and the candidate with the better voice wins on the radio. Even if Mehrabian’s 55-38-7 rule is not universally applicable, this debate clearly demonstrates how good presentation can tip the balance in your favor.

The Suggestive Power of Clothes and Status Symbols

Well-dressed people look more competent, enabling them to get their own way more easily. In a business negotiation experiment, participants wearing suits struck far better deals than those in home clothes.10

Another experiment investigated how many people would follow a man who crossed the road at a red light. In the first run, he was in a suit – in the second, he was wearing normal clothes. The result was remarkable: in business attire, three and a half times more strangers followed him.11

And while we’re out on the roads, a brief note on status symbols: in another experiment, a luxury car stopped at the traffic lights, and didn’t budge when they changed to green. In a second run of the experiment, a typical mid-range car did the same thing. No prizes for guessing which one got honked at more. The second one, of course! Almost every car behind it beeped multiple times. Three angry motorists even lightly nudged its bumper to try to spur the driver into action. Only fifty percent beeped at the fancy car – and needless to say, nobody drove into the back of it.12

Instinctively, we’ve known all this for a long time. Only in the last few decades, though, has this knowledge been proven by social psychologists in innovative experiments.

If you’re not using nice clothes and choice status symbols to impress people (within your own means, of course), you’re missing out on a surefire way to influence them effectively.

Self-Manipulation

It’s even more remarkable, but a long-established truth, that we can use our body language and clothing to manipulate our own hormonal balance. So-called high-power poses (straight posture, open body language, broad gestures) induce higher testosterone levels and a stronger sense of assertiveness and dominance, while also reducing the stress hormone cortisol in our bodies.13

Note: We can not only manipulate others, but ourselves too – though of course we should only manipulate ourselves for our own benefit. The upshot of all these experiments is unmistakable: confident body language and nice clothes make it easier for us to get our own way.

Conversely, low power poses (bowed head, folded arms and crossed legs) reduce testosterone and increase cortisol. In another experiment, job applicants who adopted high power poses before their interview performed better than those who interviewed in low power poses.14 Even just putting on a suit instead of home clothes raises our testosterone levels – giving us a better chance of getting our own way.15

3. Building a Quick Rapport

Birds of a feather flock together.

Proverb

Sympathy and trust develop only gradually, if at all, between strangers – unless you help things along a bit. Mirroring is one of the best manipulative tricks you can use to forge a bond of some sort quickly and effectively.

What Is Mirroring?

Let’s start with an everyday example of how a mirroring conversation can go. “You”, of course, refers to the expert manipulator that you are soon to become:

You: “Do you like sport?”

Them: “Yes, I love tennis.”

You: “Tennis? Ah. I used to watch a lot of tennis. Fascinating game!”