14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

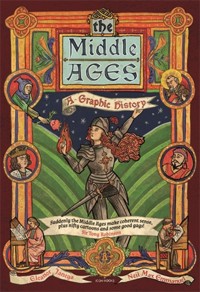

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A unique, illustrated book that will change the way you see medieval history The Middle Ages: A Graphic Historybusts the myth of the 'Dark Ages', shedding light on the medieval period's present-day relevance in a unique illustrated style. This history takes us through the rise and fall of empires, papacies, caliphates and kingdoms; through the violence and death of the Crusades, Viking raids, the Hundred Years War and the Plague; to the curious practices of monks, martyrs and iconoclasts. We'll see how the foundations of the modern West were established, influencing our art, cultures, religious practices and ways of thinking. And we'll explore the lives of those seen as 'Other' - women, Jews, homosexuals, lepers, sex workers and heretics. Join historian Eleanor Janega and illustrator Neil Max Emmanuel on a romp across continents and kingdoms as we discover the Middle Ages to be a time of huge change, inquiry and development - not unlike our own.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

1

Contents

Introduction: Common Misconceptions about the Middle Ages

4What Is the Medieval Period?

5It’s difficult to say when the Medieval Period ended because, when it did, no one had invented the concept of modernity yet. Historians sometimes date it to when Europeans went to the Americas; some to “the Renaissance” in Italy; others to the rise of Martin Luther (1483−1546), around 1517. No matter the dates, we are talking about a thousand years’ worth of history, progress, art, politics, and life. It’s also when Europe became a force in the world, and began to catch up with the empires of Asia and Africa.

The term medieval best applies to Europe, because not every part of the world experienced a move away from an ancient to a more modernized culture in that era. Historians sometimes talk about medieval China, often meaning the period up until the Song Dynasty was established in 960, which means that China became “modern” about 600 years before Europe did – bureaucratic state system, gunpowder, and international exports.

On the Yucatan peninsula, Mayan civilization experienced both their classic and post-classic periods, building impressive temple complexes that still stand today, and creating a complex society with mercantile, scholar and warrior classes and a thriving trade in cocoa, jade, and obsidian.

In India, the Rashtrakuta Empire was mining diamonds, building huge temple complexes, and trading for pearls and Italian wines. 6

The term “medieval” is confusing even within Europe. People in what we now call the Byzantine Empire would have told you that they were the Eastern Roman Empire. Their proof was in their intact state, their elaborate public chariot races, and the huge swathes of Roman land that they were still ruling over from Constantinople.

When we talk about something being medieval it can be confusing, because we are talking about a period of time, but not everyone across Europe during those dates had similar experiences. To make it more confusing, historians subdivide the Middle Ages into three categories: the Early (6th–10th century), High (10th–13th century), and Late (13th through the 15th century). So, the Middle Ages are a period of about a thousand years, between the fall of the Roman Empire and the dawn of the Modern era in Europe, with three time periods within it.

7The Myth of the Dark Ages

However, just because we don’t have a written record of something, doesn’t mean it wasn’t worth recording. Not everyone has the room to keep admin records, journals, or outdated laws for a thousand years. Even for scientific studies conducted now, destroy dates are often only a decade. Survival rates for things like fiction books can also be low. Some popular books from the 20th century survive in lower rates than medieval popular romances.

Just like you clean out your closet periodically, sometimes archives and libraries get rid of documents they don’t find useful. Sometimes − like when Henry VIII (1491–1547) dissolved the monasteries in England, Wales, and Ireland − masses of documents are destroyed. We also lose things during wars. Ways of keeping records also change. In 1,000 years could we study your Instagram profile or will you have deleted it?

Part 1. Roman Inheritance

Rome in 476 wasn’t the grand conqueror it had been. Rome had ditched Britannia, lost huge parts of what is now France, and already divided itself into two parts: Western Rome (where ground was being lost) and Eastern Rome (which we now call the Byzantine Empire). Barbarians (who the Romans defined as anyone who wasn’t Roman) had been picking away at Roman territory since they started moving to Europe about 100 years earlier, what we call the Age of Invasions.

11The Fall of Rome

A large contingent of historians think that the fall of Rome was brought about by the Germanic barbarians’ arrival. Barbarians started showing up and settling in Roman land, leading to pressure on the military, a shrinking tax base, and general disillusionment with Roman government. What was the point of paying taxes if the army didn’t even keep barbarians off your lawn?

Other historians think that Rome fell because it was already experiencing a weakening of its core. Sometimes this is blamed on the rise of Christianity and a waning of “traditional” Roman values and introduction of new theoretical “leaders” in the Church. Others point to corruption and the general willingness of the Praetorian Guard to just kill any emperor they weren’t feeling. Others point to economic issues from overexpansion and reliance on slave labor.

13Roman Successor States

The first post-Roman ruler of the Italian peninsula, Theoderic the Great (454−526), was a product of the Eastern Roman Empire, an Amal who had been raised as a hostage at the court in Constantinople.

After a lavish Roman education, the Emperor Zeno (425−91) sent Theoderic to the Italian peninsula to overthrow Odoacer, which he accomplished by killing him at a dinner.

Theoderic then set up what we call the Ostrogothic Kingdom, with its capitol in Ravenna. Although it was essentially a client state of the Eastern Roman Empire, Theoderic liked to style himself as an emperor, surrounded by Romans to ensure his government was run as closely as possible to that of the old Western Rome. This gave him legitimacy as a ruler and enabled him to push around the other kings in the area. 14

In order to convince other people that he was, in fact, Roman, Theoderic the Great used a secret weapon: Cassiodorus (c.485−c.585), a Roman who did pretty much all of his writing and administration. Cassiodorus knew exactly how a Roman would write, understood Roman statecraft, and was able to paint Theoderic as the epitome of all these things. This ensured the safety and stability of the peninsula.

As a part of his strategy to secure peace, Theoderic used marriages to secure alliances, taking a wife from the Franks, and marrying his female relatives to Burgundians, Visigoths, and Vandals.

However, Cassiodorus’ constant diplomatic writing, and every political marriage carried out under Theoderic, shows there was a massive need for diplomacy. The Roman successor states were not playing nicely, and in many ways were just as organized and had just as great a claim to Roman status as the Ostrogoths. 15

16Disagreements over who was the “rightful” Roman heir weren’t just theoretical: there was extensive fighting between the successor states. The Franks and Visigoths were constantly at war over territory in what is now southern France. Further east, when Constantinople became dissatisfied with Theoderic, as it often did, it would funnel money to Clovis and the Franks to attack the Ostrogothic kingdom.

17The Byzantine Empire

While Western Europe was in a state disharmony, life in the Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantium, went on much as it ever had. Byzantium controlled extremely prosperous areas which provided huge tax revenues, in particular the area we now call Egypt. This allowed them to continue to support a complex state system, a huge standing army, and an imperial office.

By the 6th century Byzantium was ruled by the Justinian dynasty, founded by Justin I in 518, which even reconquered some of the lands lost by the Roman Empire. 18

But it wasn’t always smooth sailing. In 532 Constantinople saw the outbreak of the Nika riots – a major uprising brought to a head around the political ramifications of … chariot racing teams.

In Constantinople, there were four major chariot teams: the reds, whites, blues, and greens. The teams took positions on political matters and even theological problems, and, like soccer hooligans now, sometimes there were riots following races. Some members on the blue and green teams had been arrested for murder during a riot. Most were hung, but a blue and a green escaped and took refuge in a church. The crowds at the races, already angry about high taxation to fund Justinian’s wars and a truce with the Sassinids in Persia next door, demanded the escapees be pardoned. They besieged the palace that Justinian was watching from. The riots lasted a week, and 30,000 people were killed.

That there were state-sponsored chariot races, and cities large enough to sustain casualties of 30,000 people, shows us just how prosperous Constantinople was. This was still the Roman Empire.

19Caesaropapism

Like in the old Western Rome, the emperor was head of the Church. Historians call this Caesaropapism. This meant that from the time Constantinople was consecrated in 330 through to the 10th century, the emperor managed the Eastern Church by overseeing ecumenical councils (meetings of high-level clergy members and theologians to decide religious matters) and appointing Patriarchs – the highest-ranking bishops – who as a group were called the Pentarchy.

Up until the end of the 8th century, the position of “pope” did exist, but it just meant being the Bishop of Rome, and not a whole lot else. During a short period that we refer to as the Ostrogothic Papacy (493–537), the Ostrogothic king essentially appointed the pope of his choice – a choice often made as a result of unsavory practices like bribery, which often led to outright schism (a split in the Church). Clearly this was not a system without its troubles, and it didn’t give the popes a whole lot of clout even when they were elected.