Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

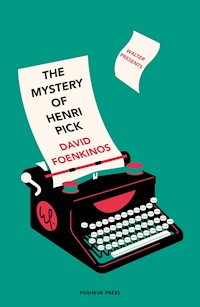

The first book in the Walter Presents library: a fast-paced comic mystery enriched by a deep love of books Readers always find themselves in a book, one way or another In the small town of Crozon in Brittany, a library houses manuscripts that were rejected for publication: the faded dreams of aspiring writers. Visiting while on holiday, young editor Delphine Despero is thrilled to discover a novel so powerful that she feels compelled to bring it back to Paris to publish it. The book is a sensation, prompting fevered interest in the identity of its author - apparently one Henri Pick, a now-deceased pizza chef from Crozon. Sceptics cry that the whole thing is a hoax: how could this man have written such a masterpiece? An obstinate journalist, Jean-Michel Rouche, heads to Brittany to investigate. By turns funny and moving, The Mystery of Henri Pick is a fast-paced comic mystery enriched by a deep love of books - and of the authors who write them. Novelist, screenwriter and director David Foenkinos was born in 1974. He is the author of fourteen novels that have been translated into forty languages. Several of his works have been adapted for film, including Delicacy (2011). The Mystery of Henri Pick is the first title in a new collaboration with Channel 4's Walter Presents.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 306

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

PUSHKIN PRESSIn association withWALTER PRESENTS

THE MYSTERY OF HENRI PICK

In a world where we have so much choice, curation is becoming increasingly key. Walter Presents was first set up to champion brilliant drama from around the world and bring it to a wider audience.

Now, in collaboration with Pushkin Press, we’re hoping to do the same thing for foreign literature: translating brilliant books into English, introducing them to readers who are hungry for quality fiction.

I discovered Henri Pick in a Parisian bookshop whilst waiting for a train. The characters and setting are quintessentially French and the mystery that lies at the heart of the book has instant international appeal. It’s a charming plot, full of twists and turns, which will keep you guessing to the very last page. A perfect first selection for the Walter Presents Library.

3

THE MYSTERY OF HENRI PICK

DAVID FOENKINOS

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY SAM TAYLOR

PUSHKIN PRESS In association withWALTER PRESENTS

THE MYSTERY OF HENRI PICK

7

“This library is dangerous.”

ernst cassirer, on the Warburg Library8

CONTENTS

PART ONE

11

1

In 1971, the American writer Richard Brautigan published The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966, a quirky love story about a male librarian and a young woman with a spectacular body. In a way, the woman is the victim of her body, as if beauty were a curse. Vida—for that is the heroine’s name—explains that a man was killed in a car accident because of her; mesmerized by the sight of this incredible passer-by, he simply forgot that he was driving. After the crash, the woman ran over to the car. The driver, covered in blood, managed to utter two last words before he died: “You’re beautiful.”

In fact, though, Vida’s story is less important than the librarian’s. Because the novel’s most distinctive feature is that the library where he works will accept any book rejected by a publisher. For example, we meet one man who deposits his manuscript there after receiving four hundred rejection slips. All kinds of different books accumulate in this way, from an essay such as “Growing Flowers by Candlelight in Hotel Rooms” to a cookery book compiling every meal eaten in Dostoevsky’s novels. One advantage of this arrangement is that the author can choose the spot on the shelf where his book will sit. He can leaf through the pages of his unfortunate colleagues before 12finding his place in this sort of anti-posterity. On the other hand, no manuscripts sent by post are accepted. The author must come in person to deliver the unwanted tome, as if to symbolize the final act of its absolute abandonment.

A few years later, in 1984, the author of The Abortion committed suicide in Bolinas, California. We will return to Brautigan’s life and the circumstances that drove him to suicide a little later, but for now let us concentrate on that library, born in his imagination. In the early 1990s his idea became a reality: one of his fans created a “library of rejected books” in tribute to the deceased author, and the Brautigan Library began to accept the world’s literary orphans. First located in the United States, it is now housed in Vancouver, Canada.1 Brautigan would surely have been moved by this initiative, although obviously it is hard to know how a dead person would feel about anything. When the library was first founded, it made the news in several countries, including France. A librarian in Crozon, Brittany, decided to do the same thing, and in October 1992 he created a French version of the library of rejects.

2

Jean-Pierre Gourvec was proud of the small sign hanging outside his library: a quote by Emil Cioran, an ironic choice for a man who had practically never left his native Brittany:

13“Paris is the ideal place to mess up your life.”

Gourvec was one of those men who prefer their region to their country, without descending into nationalistic fervour. His appearance might suggest otherwise: a tall, lean man with bulging neck veins and a very red complexion, Gourvec looked like someone with a very short fuse. But in fact he was a calm, thoughtful person, for whom words had a meaning and a destination. It took only a few minutes in his company for your false first impression to be replaced by another feeling: here was a man capable of withdrawing into himself like a Russian doll.

It was he who altered the layout of his bookshelves to create a space, at the back of the municipal library, for the world’s homeless manuscripts. That rearrangement brought back to his mind a line by Jorge Luis Borges: “If you pick up a book in a library and put it back again, you tire out the shelves.” They must be exhausted today, thought Gourvec with a smile. He had the sense of humour of an erudite man: a solitary, erudite man. That was how he saw himself, and it wasn’t far from the truth. Gourvec was endowed with a minimal dose of sociability; he rarely laughed at the same things that made his neighbours laugh, although he would pretend to whenever they told a joke. Sometimes he would even go for a beer in the bar at the end of the street, where he’d talk about everything and nothing with the other men—particularly about nothing, he thought—and in those moments of collective excitement he would occasionally agree to play cards. It didn’t bother him to be seen as a man like other men.14

Little was known about his life, other than the fact that he lived alone. He had been married in the 1950s, but his wife had left him after only a few weeks and nobody knew why. It was said that he’d encountered her through a lonely hearts ad; they had written to each other for a long time before finally meeting. Was that the reason that their marriage failed? Gourvec was perhaps the kind of man whose written declarations of love were wonderful to read, so good that you were willing to give up everything for them, but behind the beauty of his words the reality was inevitably disappointing. Some malicious gossips at the time had claimed that his impotence was to blame for his wife’s untimely departure. This theory seems improbable, but when the psychology of a situation is complex, people like to stick to the basics. In truth, nobody ever solved the mystery of that failed romance.

He had no long-term relationships after his wife left, and he never fathered children. It is difficult to know what his sex life was like. One might imagine him as the lover of neglected wives—the Emma Bovarys of his time. Some must have sought a deeper satisfaction between his bookshelves than mere words on a page. With this man who was a good listener—because he was a good reader—it was possible for a woman to escape the banal confines of her life. But there is no proof of any of this. One thing is certain: Gourvec’s enthusiasm and passion for his library never faded. He gave his full attention to every customer, striving to listen carefully to what they said so that he could create a personal journey through his book recommendations. According to him, it was not a question of liking 15or not liking to read, but of finding the book that was meant for you. Everybody could love reading, as long as they had the right book in their hands, a book that spoke to them, a book they could not bear to part with. For this purpose, he had developed a method that might appear almost paranormal: he would examine each reader’s physical appearance in order to work out which author they needed.

The ceaseless energy he put into making his library dynamic forced him to keep making it bigger. In his eyes, this was an immense victory, as if the books of the world formed an ever-diminishing army, and every act of resistance against their planned extinction was a kind of revolution. The Crozon mayor’s office even agreed that he could hire an assistant. He placed an ad in the jobs section of the local newspaper. Gourvec enjoyed choosing which books to order, organizing the shelves and many other activities, but the idea of making a decision about a human being terrified him. All the same, he nurtured hopes of finding someone who would be a literary accomplice, someone with whom he could chat for hours about the use of ellipsis in the works of Céline, or quibble over the reasons for Thomas Bernhard’s suicide. There was only one obstacle to this ambition: he knew perfectly well that he would be incapable of saying no to anybody. So the process would be simple: the person he hired would be the first one to apply. That was how Magali Croze came to join the library, thanks to the inarguable quality of having been quicker than anyone else to respond to the job offer.16

3

Magali was not particularly fond of reading2 but, as the mother of two young boys, she needed to find work as soon as possible. Particularly since her husband had only a part-time job at the Renault garage. In the early 1990s, fewer and fewer cars were being built in France, and the economic situation showed no signs of improving. As she signed her contract, Magali thought about her husband’s hands, which were always smeared with grease. At least, handling books all day, that was one unpleasantness she was likely to avoid. It would be a fundamental difference in their marriage; her hands and her husband’s were now on diametrically opposed trajectories.

When all was said and done, Gourvec liked the idea of working with someone for whom books were not sacred. It was possible, he acknowledged, to have a very good relationship with a colleague without discussing German literature every morning. He took care of recommending books to customers and she dealt with the logistics; as a working partnership, they were nicely balanced. Magali was not the kind of employee who questioned her boss’s initiatives, but she couldn’t help expressing her doubts when it came to all these rejected books.

“What’s the point of stocking books that nobody wants?”

17“It’s an American idea.”

“So?”

“It’s a tribute to Brautigan.”

“Who?”

“Richard Brautigan. Haven’t you read Dreaming of Babylon?”

“No. But anyway, it’s a weird idea. And do you really want them to bring their books here? We’ll get stuck with all the psychopaths in the area. Writers are mad, everybody knows that. And ones who aren’t published… they must be even worse.”

“They’ll finally have a place. Think of it as charity work.”

“I get it: you want me to be the Mother Teresa of failed writers.”

“Yeah. Something like that.”

“…”

Magali gradually came around to the idea, and tried to bring a positive attitude to the new venture. Jean-Pierre Gourvec ran an ad in some trade magazines, notably Lire and Le Magazine Littéraire, inviting all authors who wished to deposit their manuscript in the library of rejects to visit Crozon. The idea quickly took off, and many people made the journey. Writers came from all over France to rid themselves of the fruits of their failure. It was a sort of literary pilgrimage. There was a symbolic value in travelling hundreds of miles to put an end to the frustrations of not being published. Their words were erased, like sins. And perhaps there was something symbolic, too, about the name of the département where Crozon was located: Finistère, the ends of the earth.18

4

In the ten years that followed, the library welcomed nearly a thousand manuscripts. Jean-Pierre Gourvec spent his time observing them, fascinated by the power of this useless treasure. In 2003, he became seriously ill and was hospitalized for a long time in Brest. This was doubly harsh in his eyes: his failing physical health bothered him less than being torn away from his books. He continued sending Magali instructions from his hospital bed, keeping his finger on the pulse of the literary world so he would know which books to order. He didn’t want to miss anything. He poured the last of his strength into his lifelong passion. The library of rejected books no longer seemed to interest anybody, and that made him sad. After the excitement of its beginning, it was kept alive now only by word of mouth. In the United States too, the Brautigan Library was starting to flounder. Authors were no longer abandoning their unwanted books there.

When Gourvec returned from the hospital, he was much thinner. You didn’t need to be a fortune teller to realize that he did not have long left to live. The town’s inhabitants, in a sort of kindly reflex, were seized by a sudden desire to borrow books. Magali had fomented this artificial bookmania, understanding that it was the one thing that would make Jean-Pierre happy. Weakened by his illness, he didn’t suspect that there was anything unnatural about this sudden surge of readers. On the contrary, he let himself believe that his long years of hard work were finally bearing fruit. He would leave the world soothed by this satisfying knowledge.19

Magali also asked several of her acquaintances to quickly write a novel so that they could fill the shelves of the library of rejected books. She even got her mother involved.

“But I’ve never written anything in my life.”

“Exactly. It’s time you did. Write down your memories.”

“But I don’t remember anything. And I’ve committed so many sins.”

“Nobody cares, Mama. We need books. Even your grocery list will do.”

“Oh really? You think people would be interested in that?”

“…”

In the end, her mother decided to copy out the phone book.

Writing books that were intended for the library of rejects was a far cry from the original project, but Magali didn’t care; the eight books that she collected within the space of a few days made Jean-Pierre very happy. He saw it as a stirring of hope, a sign that all was not lost. He knew he wouldn’t be able to witness the library’s recovery for much longer, so he made Magali promise that she would at least keep all the rejected books they had accumulated up to now.

“I promise, Jean-Pierre.”

“Those writers put their trust in us… We can’t betray them.”

“I’ll look after them. They’ll be protected here. And there will always be a place for books that nobody wants.”

“Thank you.”

“Jean-Pierre…”

“Yes?”

“I wanted to thank you…”20

“For what?”

“For giving me The Lover… It’s such a beautiful book.”

“…”

He took Magali’s hand and held it for a long time. A few minutes later, alone in her car, she started to cry.

*

The following week, Jean-Pierre Gourvec died in his bed. People talked about him as a lovable man who would be missed by everyone. But very few mourners attended the brief ceremony at the cemetery. What would remain of this man, in the end? On the day of his funeral, it was perhaps possible to understand his determination to create and expand the library of rejected books. It was a sort of gravestone, a bulwark against oblivion. Nobody came to lay flowers at his graveside, just as nobody came to read the rejected books.

*

Of course Magali kept her promise to look after the books they’d already acquired, but she had no time to seek out new ones. For the last few months, the local government had been trying to cut spending, particularly on anything cultural. After Gourvec’s death, while Magali took over the running of the library, she was not allowed to hire an assistant. She found herself alone. Gradually, the shelves at the back of the library would be abandoned, and dust would cover those unread 21words. Magali was so busy carrying out more pressing tasks that she rarely spared a thought for the rejects. How could she possibly imagine that they would one day turn her whole life upside down?22

1For more information, go to www.thebrautiganlibrary.org

2When he first laid eyes on her, Gourvec immediately thought: she looks like someone who would adore The Lover by Marguerite Duras.

PART TWO

25

1

Delphine despero had lived in Paris for almost ten years, kept there by work commitments, but she had never lost her attachment to Brittany. She appeared taller than she actually was, and the illusion had nothing to do with high heels. It’s difficult to explain how some people manage to grow in this way: is it ambition, the fact of having been loved as a child, the certainty of a radiant future? Maybe a little of all of this. Delphine was the kind of woman you wanted to listen to, to follow; she had a kind of gentle charisma. Her mother was a literature teacher, and she was born among words. She spent her childhood examining the essays written by her mother’s students, fascinated by the red ink of correction; she scrutinized their mistakes, their awkward sentences, memorizing all the things she shouldn’t do.

When she finished secondary school, she went to the University of Rennes to study literature, but she had no desire to become a teacher. Her dream was to work in publishing. She spent her summers doing internships or any work that would allow her to enter the literary world. She had realized very early in life that she didn’t feel capable of being a writer; she was not frustrated by this, but more than anything she wanted 26to work with writers. She would never forget the frisson she felt the first time she saw Michel Houellebecq. At the time, she’d been an intern at Éditions Fayard, who had published The Possibility of an Island. He had paused for a moment in front of her, not really to look at her, but rather, let’s say, to sniff her. She had stammered hello and received no response, and to her this seemed the most extraordinary conversation of her life.

The following weekend, back at her parents’ house, she’d spoken about that moment for more than an hour. She admired Houellebecq and his incredible novelistic sensibility. She was bored by all the controversies surrounding him; nobody ever paid enough attention to his language, his despair, his humour. She talked about him as though they were old friends, as if the simple fact of having passed him in a corridor enabled her to understand his work better than anyone else. She was in a state of exaltation, and her parents watched her with amusement; they’d done everything they could, when educating their daughter, to fill her with enthusiasm, fascination, wonder; in this sense, they had clearly succeeded. Delphine had developed an ability to sense the interior drives that gave life to a narrative. Everyone who met her during this period agreed that she had a promising future.

After an internship at Grasset, she was hired as a junior editor. She was exceptionally young for such a position, but all success is the fruit of good timing; she had appeared in the publishing house at a time when the management wished to make the editorial team younger and more female. She was given a few authors—not the most prestigious, it has to 27be said, but they were all happy to have a young editor who would devote all her time and energy to them. She was also expected to look at the unsolicited manuscripts they received whenever she had some spare time. She was the one who discovered Laurent Binet’s extraordinary first novel, HHhH. As soon as she finished it, she hurried to see Olivier Nora, the CEO of Grasset, and urged him to read it as soon as possible. Her enthusiasm was rewarded. Binet signed with Grasset just before Gallimard offered him a contract. A few months later, the book won the Prix Goncourt for a First Novel, and Delphine Despero was given a promotion.

2

A few weeks after that, she was filled once again with a rush of enthusiasm when she read the first novel by a young author named Frédéric Koskas. The Bathtub was about a teenage boy who refused to leave the bathroom and decided to live inside the bathtub. The story was written in prose that was simultaneously joyous and melancholic, and Delphine had never read anything like it. She had no trouble convincing the reading committee to follow her advice by making an offer for the book. She was reminded of Goncharov’s Oblomov and Calvino’s Baron in the Trees, but there was also a contemporary dimension to the theme of the protagonist’s rejection of the world. The biggest difference was that, thanks to the internet, twenty-four-hour news, social media and so on, every adolescent in the world 28could potentially know everything there was to know about life… so why bother leaving the house? Delphine was capable of talking about this novel for hours on end. She immediately considered Koskas to be a genius. Despite her easily aroused excitement, this was a word that she used only rarely. However, we should bear in mind one additional detail: she had fallen head over heels in love with the author of The Bathtub.

They met several times before the signing of the contract: first, in the offices of Grasset, then in a café, and lastly at the bar of a posh hotel. They spoke about the novel together, and about how it would be published. Koskas’s heart pounded at the thought that he would soon have a novel in print; this was his ultimate dream, his name on the cover of a book. He felt certain now that his life was about to begin. With his name on a novel, he had always imagined that he would become a floating being, torn free of all roots. He told Delphine about his influences, and they chatted about their favourite authors—she was very well read—but never did their conversation drift into the realms of intimacy. The young editor was dying to know if her new author had a girlfriend, but she never allowed herself to ask him that question. She tried to find out through more indirect means, but in vain. In the end it was Frédéric who made the first move.

“May I ask you something personal?”

“Yes, of course.”

“Do you have a boyfriend?”

“You want me to be honest?”

“Yes.”29

“I don’t have a boyfriend.”

“How is that possible?”

“Because I was waiting for you,” Delphine replied, surprising herself with her spontaneity.

She wanted to take the words back as soon as they were out of her mouth, to say that she was just kidding, but she knew perfectly well how sincere she had sounded. Of course, Frédéric had played his own part in this dialogue of seduction by asking her “How is that possible?” Clearly that implied that he liked her, didn’t it? She sat there blushing, while gradually admitting to herself that her words had been dictated by her true feelings—feelings that were pure, and therefore uncontrollable. Yes, she had always wanted a man like him. Physically and intellectually. It’s sometimes said that love at first sight is actually the recognition of a desire that has always existed inside us. From their first meeting, Delphine had felt this—the sensation that she already knew this man, that she had perhaps glimpsed him in premonitory dreams.

Frédéric, taken by surprise, didn’t know what to say. To him, Delphine had seemed completely sincere. When she praised his novel, he could always detect a hint of hyperbole. A sort of professional obligation to appear upbeat, he imagined. But here, the tone was bereft of irony or exaggeration; her meaning could only be taken at face value. He had to say something, and the future of their relationship hung on the words he chose. Wouldn’t he prefer to keep her at a distance? To concentrate uniquely on interactions related to his novel, and the ones he would write in the future? But there was already a connection. 30He could not be indifferent to this woman who understood him so well, this woman who had changed his life. Lost in the labyrinth of his thoughts, he forced Delphine to speak again:

“If my attraction for you isn’t reciprocated, I will of course publish your novel with the same enthusiasm.”

“Thank you for clarifying that.”

“You’re welcome.”

“So, let’s say we were together…” said Frédéric in a suddenly amused tone of voice.

“Yes, let’s say we were…”

“If we ever split up, what would happen?”

“Wow, you’re really pessimistic. Nothing has even started yet, and you’re already talking about it ending.”

“I’d like an answer, though: if one day you end up hating me, will you have all the copies of my book pulped?”

“Well, yes, obviously. That’s just a risk you’ll have to take.”

“…”

He stared at her, and started to smile, and that was how it all began.

3

They left the bar and went for a walk through the streets of Paris. They became tourists in their own city, wandering around aimlessly before arriving at Delphine’s apartment. She rented a bedsit near Montmartre, a neighbourhood that can’t decide if it’s working class or bourgeois. They climbed the 31stairs leading to the second floor: a sort of foreplay. Frédéric watched Delphine’s legs, which, aware of being observed, advanced slowly. Once inside the apartment, they headed to the bed and lay down without any frenzy; sometimes, the most intense desire can lead to a calmness that is just as exciting. Soon after that, they made love. And remained in each other’s arms for a long time, the two of them struck by the wonderful weirdness of being suddenly and completely intimate with somebody who, a few hours before, had still been a stranger. The transformation was rapid, it was glorious. Delphine’s body had found the destination it had sought for so long. Frédéric felt finally at peace; a void that he hadn’t even realized was inside him had been filled. And they both knew that what they’d experienced simply never happened. Or only to other people. In the middle of the night, Delphine turned on the light.

“It’s time to talk about your contract.”

“Ah… so this was a negotiating tactic…”

“Naturally. I sleep with all my authors before signing. It makes it easier to retain audiovisual rights.”

“…”

“So?”

“You can have them. You can have all my rights.”

4

Unfortunately, The Bathtub was a failure. And yet “failure” is perhaps an overstatement. What can anyone expect from the 32publication of a novel? Despite all Delphine Despero’s efforts, despite all her contacts in the press, despite several reviews praising the inspired storytelling of this promising talent, Frédéric’s novel suffered the classic destiny of most published novels. When you are unpublished, you believe that the holy grail is publication. But there is a fate worse than the pain of not being published: being published in complete obscurity.1 After only a few days, your book is nowhere to be seen, and you find yourself somewhat pathetically wandering from one bookshop to the next in search of some proof that it wasn’t all a dream. Publishing a novel that nobody reads is like encountering the world’s indifference in person.

Delphine did her best to reassure Frédéric, telling him that this setback had not diminished Grasset’s faith in him. But nothing worked: he felt empty and humiliated. He had lived for years with the certainty that one day he would exist through words. He had enjoyed the image of being a young man who writes and who, soon, will have a first novel published. But what could he hope for now that reality had dressed his dream in rags? He had no desire to play-act, to go into false ecstasies over the critical acclaim his novel had received, like so many others who boast about a three-line mention in Le Monde. Frédéric Koskas had always viewed his situation objectively. And he realized that he shouldn’t change what was now his defining characteristic. People didn’t read him; that’s just how 33it was. “At least I met the woman I love through publishing this novel,” he thought consolingly. He had to keep going, with the conviction of a soldier who’s been left behind by his regiment. A few weeks later, he started writing again. A novel with the provisional title of The Bed. He didn’t tell Delphine what the book was about. All he said was: “If it’s going to be another failure, it may as well be more comfortable than a bathtub.”

5

They moved in together. In other words, Frédéric moved his stuff to Delphine’s apartment. To protect their love from gossip, they kept it a secret within the publishing house. In the morning, she went off to work and he sat down to write. He had decided to write this new book entirely in their bed. Writing provides you with some extraordinary alibis. Writing is the only job in the world where you can stay under the duvet all day long and still claim to be working. Sometimes he fell back asleep or daydreamed, persuading himself that it was useful for his creativity. The reality, however, was that his creativity was all dried up. It occurred to him that this lovely, comfortable happiness that had fallen from the sky might actually be damaging his ability to write. Did you have to be lost or fragile in order to create? No, that was absurd. Masterpieces had been written amid euphoria and masterpieces had been written amid despair. In fact, for the first time in his life, there was a support structure to his existence. And Delphine could earn 34enough money for both of them while he wrote his book. He didn’t think of himself as a parasite or a helpless person, but he’d accepted the idea of being kept. It was a sort of lovers’ pact: he was working for her, after all, because she would publish his novel. But he also knew that she would judge the book impartially, that her love for him would have no effect on her opinion of the novel’s quality.

In the meantime, she was publishing other authors, and her reputation as an editor continued to grow. She turned down several offers from other publishers because she felt profoundly attached to Grasset, the company that had given her the big break she’d craved. Occasionally Frédéric would get jealous. “Oh really? You published this book? But why? It’s so bad.” She replied: “Don’t become one of those embittered authors who finds all other books unreadable. I have to deal with too many egotistical bores all day. When I get home, I want to see an author focused entirely on his work. The others don’t matter. Besides, I’m just publishing them while I wait for your bed. Everything I do in life is basically waiting for your bed.” Delphine had a brilliant knack for defusing Frédéric’s anxieties. She was a perfect mix of a literary dreamer and a pragmatic woman; she drew her strength from her origins, and from the love of her parents.

6

Ah yes, her parents. Delphine talked to her mother on the phone every day, recounting her life in minute detail. She talked to 35her father too, but the version she gave him was more succinct. The two of them were both recently retired. “I was raised by a French teacher and a maths teacher, which explains my schizophrenia,” Delphine would joke. Her father had taught in Brest, and her mother in Quimper, and every evening they would return to their home in the village of Morgat, near Crozon. It was a magical place, a refuge, dominated by the wildness of nature. It was impossible to be bored in a place like that; you could fill a whole life with contemplation of the sea.

Delphine spent all her summer holidays at her parents’ house, and this one was no exception to that rule. She asked Frédéric to come with her. It would be an opportunity for him to finally meet Fabienne and Gérard. He pretended to hesitate, as if he might have something better to do. He asked her: “What’s your bed like?”

“Unsullied by any man.”

“So I’d be the first to sleep with you there?”

“The first—and the last, I hope.”

“I wish I could write the way you answer my questions. What you say is always so beautiful, powerful, precise.”

“You write better than that. I know that better than anyone.”

“You’re wonderful.”

“You’re not bad yourself.”

“…”

“It’s the end of the world, where my parents live. We’ll go for walks by the sea, and everything will be clear.”

“And your parents? I’m not always very sociable when I’m writing.”36

“They’ll understand. We talk all the time, but we don’t expect anyone else to do the same. That’s Brittany.”

“What does that mean, ‘That’s Brittany’? You say that all the time.”

“You’ll see.”

“…”

7

Things didn’t go quite like that. As soon as they arrived in the house, Frédéric felt warmly devoured by Delphine’s parents. He was the first boyfriend she’d ever introduced to them; that was obvious. They wanted to know everything. So much for the supposed non-obligation to talk. He was uncomfortable with the idea of digging up the past, but they immediately interrogated him about his life, his parents, his childhood. He tried to throw them tokens of sociability, sprinkling his answers with charming anecdotes. Delphine had the feeling that he was inventing these stories to make his life sound more thrilling than the bleak reality. She was right.

Gérard had read The Bathtub. It is always slightly depressing for an author who has published an unsuccessful book to meet a reader who tries to make them feel better by talking about it interminably. Of course, the intention is a good one. But, barely had they arrived, drinking the first aperitif on the terrace, overlooking that breathtakingly beautiful landscape, than Frédéric felt embarrassed that the moment should be 37encumbered by a conversation about his novel, which was, he thought, ultimately pretty mediocre. Gradually, he was beginning to detach himself from it, to perceive its faults, its try-hard prose. As if every sentence had to provide immediate proof of its author’s brilliance. A first novel is always a bit of a teacher’s pet. Only geniuses can instantly produce dunces. But it undoubtedly takes time to understand how to let a story breathe, how to create something behind the shows of brilliance. Frédéric had the feeling that his second novel would be better; he thought this constantly without ever mentioning it to anyone. He didn’t want to spread his intuitions too thin by sharing them.

“The Bathtub is an excellent parable of contemporary life,” Gérard went on.

“Ah…” replied Frédéric.

“You’re right: profusion created confusion, to start with. And now it is producing a desire for renunciation. If everything is of equal value then nothing means anything. A very pertinent equation, in my opinion.”

“Thank you. You’re making me blush with all these compliments…”

“Better enjoy them. It’s not normally like that around here,” he said, laughing a little too heartily.

“I sensed the influence of Robert Walser. Am I right?” Fabienne asked.

“Robert Walser… I… yes… it’s true, I like his work a lot. I hadn’t thought about him as an influence, but you’re probably right.”38

“Your novel reminded me most of all of his short story, ‘The Promenade’. He has an incredible talent for evoking the act of walking. Swiss authors are often the best when it comes to boredom and solitude. There’s some of that in your novel: you make emptiness fascinating.”

Frédéric was speechless; he felt choked by emotion. When had he last felt such kindliness, such attention? In a few phrases, they had bandaged the wounds left by the public’s incomprehension. He looked at Delphine, who had changed his life, and she smiled at him very tenderly. He thought how eager he was to discover that famous bed where no man had been before him. Here, their love seemed to have ascended to a higher plane.

8

After this chatty introduction, Delphine’s parents didn’t ask Frédéric too many questions. The days passed, and he took great pleasure in writing and in exploring this region that was, for him, unknown. He wrote in the mornings, and in the afternoons he went walking with Delphine, roaming the countryside and never meeting anyone. It was the ideal setting in which to forget himself. Here and there, she would tell him anecdotes about her adolescence. The past came together bit by bit, and now Frédéric was able to love every era of Delphine’s life.