9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

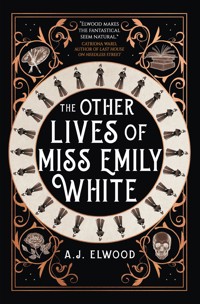

An eerie tale of young girls' obsession and what happens when it grows out of hand, perfect for fans of dark academia, The Secret History and Picnic at Hanging Rock. 1864. Banished from her parents' farm to a boarding school for young ladies, Ivy feels utterly alone. In a crumbling and isolated seminary that has seen better days, she is shunned by the other pupils for her working-class origins, and mourns for her sister, who died not long after she was sent away. Hope comes in the form of a new teacher, Miss Emily White, but almost immediately, suspicions are raised that she is not all she should be. Ivy is captivated, yet as her devotion grows, odd reports begin to circulate that Miss White has been glimpsed in the garden picking flowers whilst also teaching a class, leaving the school but stalking the halls at the same time. As increasingly strange rumours abound, Ivy's obsession spins out of control, and with Emily White's future at stake, she will do anything to keep her only friend.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

Acknowledgements

About the Author

“Elwood is today’s supreme author of the Victorian uncanny. She plunges you in and doesn’t let you go. I’m addicted.”Stephen Volk, writer of BBC Films’ The Awakening, author of The Dark Masters Trilogy

“Delicately disturbing, elegantly uncanny, A. J. Elwood’s novel shuts us in a school where even the ghostly can be a release and leads to a conclusion that’s as poignant as it is disquieting. A real treat for connoisseurs of the classic supernatural tale.”Ramsey Campbell, “Britain’s most respected living horror writer,” Oxford Companion to English Literature

“The Other Lives of Miss Emily White is a gothic treat: class, femininity and the hothouse atmosphere of a Victorian boarding school make the perfect backdrop for a story of obsession and hysteria. Elwood’s way with words is absolutely enchanting, and I didn’t want this book to end, but when it did…!”Ally Wilkes, author of All the White Spaces

“Darkly enthralling, with a deftly woven and sinuous plot, secrets abound in this beguilingly gothic tale of teenaged obsessions and sinister manifestations.”Lucie McKnight Hardy, author of Water Shall Refuse Them

“A hugely atmospheric tale set in the repressed atmosphere of a young ladies’ Victorian boarding school, that will have you looking over your shoulder at every sound.”Marie O’Regan, author of The Last Ghost and Other Stories, editor of Phantoms, Cursed and Wonderland

“Readers beware! The mystery at the heart of A. J. Elwood’s latest eerie and elegant novel is so irresistibly tantalising that everyday commitments will fall by the wayside as you feel compelled to read ‘just a few more pages’, and then ‘just a few more’, in your bid to uncover the truth.”Mark Morris, author of the Obsidian Heart trilogy

“Enough to make you scared of your own shadow.”Priya Sharma, author of Ormeshadow

“A. J. Elwood has carved a solid reputation with her spooky and hauntingly beautiful historical fiction. This novel is no exception, and its brilliance surely cements her place as one of the finest British writers working today in any genre.”Tim Lebbon, author of Eden and The Last Storm

“A. J. Elwood draws us into an intricate, clastrophobic world brimming with menace. The strange after-image of Emily White will linger with readers long after the final page.”Verity M. Holloway, author of The Others of Edenwell

Also by A. J. Elwood and available from Titan Books

THE COTTINGLEY CUCKOO

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Other Lives of Miss Emily White

Print edition ISBN: 9781803363707

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803363714

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP.

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: April 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Alison Littlewood 2023

Alison Littlewood asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

LONDON 1922

It is one of those brilliant winter days, the sky as fragile as innocent youth and just as distant, although the air has a chill in it that touches my bones. Through the window the plane trees grasp at the brightness, their claws blacker by the contrast, unless it is only that they are darkened by all the pollution of this London street. They are said to be the only kind of tree that will grow here, able to withstand the soot that must have accumulated in layers since I was young; but still another plant twines around them, its leaves unnoticed and dusty, yet alive, even thriving.

Soon I shall be alone in these rooms and may consider those times. Inwardly I must have done so for upward of fifty years, for the days of my girlhood remain as clear to me as the one passing by outside; perhaps more so, since they have never left me, though this one, like so many others, shall.

There is a footfall on the stairs.

My dearest does not come in. A soft-spoken farewell reaches only my own ears and I hear the opening and closing of a door. We have a maid who comes in and helps clean and wash, but it is not her day and I expect no one; the house is empty.

This is what I have been waiting for, a little space of time alone, though I am still uncertain whether I can face making such a deliberate recollection. But I am old, and do not know when the chance will be taken from me; the days left for me to think of matters of the soul may be growing few. Of course, Society would have it that I am damned already. It may be that I was always bound for hell and there is no changing anything, but why then should anything remain to make me afraid? For I am afraid, though I keep it so well hidden I am no longer sure how to recognise it.

I stir from my place at the dressing table. That too belongs to another time, with its boar-bristle hairbrush, selection of hat pins, stoppered scent-bottles and cold cream in a ceramic pot, a design of daisies dancing around the rim. There is also the mirror. For many years I have disliked looking at my own reflection, even a glimpse as I pass along a hallway – perhaps especially that. I must sit there and arrange my hair and dress each day, but still I try not to see the figure in front of me. I prefer it to remain so hazy and unfocused it might be anyone. Originally this particular mirror was a tri-fold, but that I couldn’t abide and had the side panels removed. I didn’t like, when I leaned over the table to select a brooch or a pin, to see from the tail of the eye my image multiplied, receding away all about me; every one the same.

I walk into the drawing room, which is high-ceilinged and respectable and a little cold. It has all that pertains to such a room: the dignity of mahogany, the solidity of table and chairs, the showiness of gilt candelabra, the femininity of objets de vertu, the industry of needle-worked fire-screens and stools. These too belong to the past – they were here when I took the house – but I have little interest in such things and never troubled to dispose of them. There is also an embroidered motto in a frame: SEE NO EVIL. It makes no mention of hearing or speaking, and I often wonder why. Perhaps it was originally one of a set and its sisters have long since been lost.

And here is that item which Society decrees must belong in every drawing room, proper in every respect: a mirror set over the fireplace, taller than it is wide – of course, since the opposite would suggest low ceilings, compromise, even poverty. This has a carved design that might have been chosen for my name: Ivy. The clinging leaves are frozen in silver gilt, though they still possess the semblance of life: something that could grow, twine; cling.

‘Faithfulness,’ I whisper. And a shadow appears in the glass as I approach, though I don’t immediately raise my head.

When I look, my appearance surprises me. It always does. Am I really this pale, crape-skinned creature? I’ve always been full of thoughts, feelings, colours. I once raced across a farmyard bellowing for Scampers, the old dog, to chase after me. I twined my fingers in a horse’s mane so tightly my skin wore its imprint for hours. I had scabbed knees, a smeared pinafore, dirty shoes. My hair was lit with red and flying loose and I didn’t know there was anything wrong in any of it, not then.

Now my countenance is blank and mild, nothing to offend, the image of what an old lady should be. My gown is neat and respectable. My hair, once so resistant to the brush and carrying that hint of rebellious red, has been tamed at last and turned entirely grey. I might have stepped out of the last century, though we are over twenty years into the next and there are more motor cars than carriages passing by outside. Skirts and hair are shorter, necklines lower, heels higher. There is new music and new freedom – something I once craved. Does it come to everyone, this being left behind? Or is it only that I never really moved on, and a part of me remains in Fulford, despite all I have done with my life?

It is ironic that I should be the one to appear so traditional. But mine isn’t the face I am thinking of: the one that has troubled me, followed me, haunting my dreams and my waking hours alike for so many years, always so close I half expect her to appear in the mirror at my side, peeking over my shoulder.

Miss White. Mademoiselle Blanc. Emily.

I steal a glance behind me as if she really might be standing there. As if she might at any second touch my shoulder.

The eyes reflected in the mirror meet my own and a prickle of electricity jolts me to my fingertips.

I was a child. I had no conception of what would happen. I couldn’t peer into the future as I do now into the past. I can change none of it, though I see it still; I recall, quite clearly, my thoughts when I first saw her. My feelings, however, remain jumbled; the emotions I had first and those that came after are like a dimly seen reflection, partly illuminated but much remaining dark.

I am still not certain I can unravel everything that happened, or begin to understand. I only know that she was my teacher, and I loved her.

I close my eyes and she rushes towards me.

YORKSHIRE 1864

The female character should possess the mild and retiring virtues rather than the bold and dazzling ones; great eminence in almost anything is sometimes injurious to a young lady; whose temper and disposition should appear to be pliant rather than robust; to be ready to take impressions rather than to be decidedly mark’d; as great apparent strength of character, however excellent, is liable to alarm both her own and the other sex; and to create admiration rather than affection.

Erasmus Darwin,A Plan for the Conduct of Female Education in Boarding Schools

A D V E R T I S E M E N T :Young ladies’ boarding school atMiss Dawson’s Seminary, Snaithby Dun.

For the daughters of independent gentlemen and professional men. Plain and ornamental needle work, music, dancing, painting. Also languages, grammar, history, geography, &c. &c. Twenty guineas p.a., no entrancemoney, no vacation. The situation is commodious and delightful with extensive gardens and good air. The strictest attention is paid to health, morals and improvement, and to the duties of piety.

* * *

It began one dull afternoon, the sky grey, the room likewise, when the eyes of twenty-six well-bred young ladies – and mine – turned to the rain-smeared windows to await the arrival of our new schoolmistress.

The weather was a disappointment, and not only because it was summer. We’d been hoping for it to brighten ever since the carriage left, though its veneer still shone with polish. Our headmistress would have insisted on that; it was going to town, after all, where common eyes might see and judge. As such, she preferred a flashy Clarence to a more practical wagonette, along with a pair of chestnut horses: perfectly matched, perfectly gleaming, perfectly in stride. Bard gave a little kick as he trotted away, likely shaking stones from his hooves. The turning circle by the front entrance, where guests alighted, was surfaced in neatly raked gravel. The lane itself, less closely examined, had fallen into disrepair, the gravel thinned until there was little but unmade earth. Every departure was announced by the rattle of iron-rimmed wheels on stones, followed by a softer hum before silence took its place.

Now we listened for those sounds in reverse, twenty-seven faces turning periodically to the window like sunflowers seeking new light. We all wanted the steady, persistent, railed-against rain to cease, so that when it returned, the carriage windows would be clear enough to glimpse its occupant. She was the source of much speculation and not a little hope.

All our established mistresses were as much a part of the seminary as the wainscoting and parquet and smell of ancient mothballs; as much as the dust or silence or air of impending disapproval. They were old and therefore dull, and we longed for the pure fresh breeze of springtime even if true spring was behind us, leaving only this dreary semblance of summer.

‘Do you think she’ll be elegant?’ That was Grace’s whisper.

Matilda turned to her and rolled her eyes, as if to say, Of course she will. She is to teach us, after all.

I sighed. I hoped for kindness rather than elegance – but then, I wasn’t born to this like the rest of them. It was another sign, I supposed, that I wasn’t all I should be, and I said nothing – as I so often did. A memory of my mother’s voice came to me: Such a funny, secret child you are, Ivy. She had said that to me often, though I didn’t quite think she’d meant that I made her laugh.

Twenty-seven sighs hung before our faces, clouding the glass, since the windows were closed. The school promised good air, but not here, not now; for one thing the day was too damp, which, heaven forbid, might strain our delicate feminine lungs. For another, we were in the eyrie.

This was Fulford’s highest and largest room. It would be dangerous to open a window; they stretched up to the ceiling and down to the floor, as impressive as the space around us. The building had been part grand residence, part folly, and the eyrie took up most of the fourth storey, reduced only by little slices for the staircases. It must have once been used for balls and fancy gatherings. Now delicate yellow paper peeled from the plaster just as waltzes had faded from the air. The floorboards were whitened from scrubbing with liquid carbolic, rather than polished. A roughly constructed dais accommodated our assemblies and there was a piano, though its keys were silent and covered. There were a few cupboards of dulled wood, a coat-stand or two, some unremarkable paintings of better times and a portrait of the gentleman who had conceived the whole affair. None of us knew his name.

Still, the views were magnificent. To each side the landscape swept away, all the ploughing and planting and reaping and gleaning of the countryside reduced to stillness and ease by the distance.

I twisted to see better and was rewarded by a dig from my corset. When I came here, I’d stood on this windowsill and pressed my nose to the glass. It wasn’t forbidden, but it was the first time the others scorned me; that had been enough.

‘Back to your sewing, girls.’ Sophia’s voice carried easily; her clap, for emphasis, snapped around the room’s empty corners. At sixteen, Sophia McKenzie Bideford was almost ready to leave, and liked to think we were already far behind her; or perhaps below. She was the daughter of a banker, one who’d managed to marry old money, and kept six servants – which I believed, though servant-keeping was a competitive pursuit and I often wondered if half of those spoken of by the girls were anything more than imaginary. We had been placed in her tender care, to practise our fancy-work in the eyrie’s generous light, while the teachers – well, perhaps they awaited our new arrival as keenly as we did.

We returned to our samplers and silk threads and silver needles. I’d have preferred to hook a rag rug for my bedside to warm my first step into the day – I could have done it in a trice – but that was too practical. We were to be ladies, and I should be grateful, though it was all so tedious. I hid my expression as I bent over my embroidery frame, ‘Thou Shalt . . .’ already in place, and resumed my stitching. I still couldn’t resist stealing glances at the window, which remained as dreary and rain-speckled as ever. The patter of droplets striking the glass sounded like spite.

* * *

Shhhhhhhhh . . .

The rumbling was as faint as a hush, but we all heard it. I pictured the horses trotting along the earthen track, throwing out their matching legs, tossing their matching heads, snorting foam from matching lips. Surely our new teacher would be peeking out? She must long to see her new home as much as we longed to see her. I pictured a gentle, oval face, and told myself she would be kind. She’d be sweet and pretty and sympathetic to girls torn from their homes and brought to this starched, stifling place. She’d have a comforting smile, a low voice, soft eyes with long silken lashes.

Another face rose before me for a moment, quite different to the image I painted, and laughing at me a little – a face so dear to me yet so very distant, and I pushed the vision away.

The rattle of wheels amplified. Through the window, in the grey afternoon, appeared a peculiar sight.

At first I didn’t notice what was wrong. The carriage was there, just as we’d expected. Light sparkled from the raindrops clinging to its roof, though it wasn’t raining any longer, certainly not, and twenty-seven breaths were held in twenty-seven throats.

The carriage approached, not at its usual pace but steadily, and as it grew closer I saw that it was no longer symmetrical. The picture was ruined, for the horse was no longer half of a pair. Only one remained, pulling with visible effort, straining his neck, hesitating slightly before placing his hooves.

Which is it?

I hoped, suddenly and deeply, that it was Captain who’d come back and not Bard. Of course, I shouldn’t have a preference; none of the others would dream of learning the horses’ names. I hadn’t meant to myself. I’d once thought I might find friends among the girls, that we’d walk arm in arm and laugh, even forget our corsets and crinolines sometimes and run as if we were free. They’d never be like my sister of course, not like Daisy, but no one could ever be that. And in those first sweet days, it seemed I had found such a one – but I lost her again, or rather she was taken from me. And so I’d made a friend of a horse.

I strained to make out Captain’s features but the angle was too steep and everything was darkened with rain. Gadling, coachman and groom, flicked his whip and adjusted his course; with a horse missing, the carriage pulled to one side. Everything was crooked, off-kilter: wrong. One, where two should have been.

‘The blinds are drawn!’

Lucy was right. As the carriage turned, its windows revealed nothing but a blank. Worse followed, for Gadling didn’t rein in the carriage at the entrance, by its stone stairs – scrubbed daily – and double doors. Our new teacher wouldn’t see the hopeful motto carved above them: Ex Solo Ad Solem – From the ground to the sun. He drove on past, towards the back of the building and the stables, and twenty-seven young ladies gave up all thought of sewing and hurried for the stairs.

Sophia called out ‘Follow me, girls,’ as she pushed her way through to the front. She would already be working out her excuses for leaving the room. No doubt she’d say that we simply must greet our new schoolmistress properly, that we didn’t wish to appear rude. If in doubt, blame good manners. They couldn’t punish us for that.

We were a dark flood of skirts topped by a white froth of muslin. We knew the new teacher must use the servants’ entrance, and she’d go in search of a welcome, following a wide central corridor to the entrance hall at the front. We flowed, not down the narrow stairs set into the southern towers – we weren’t following in the servants’ footsteps – but the grand staircase shown off to benefactors, governors, prospective parents and the parson. Two flights down, we reached a gallery, all barley-sugar twists of polished walnut wrapping around the first-floor landing. From here, we could look out and down over the entrance hall. We could see her arrive, even offer our assistance.

No one paused to consider what her response to twenty-seven offers of help might be, where one might be preferred; but who would stay behind? We were destined to serve the needs of fathers and brothers and husbands and children, but we weren’t as self-sacrificing as that.

We spread ourselves along the banisters. The only sound was the ticking of the pendulum clock at the foot of the stairs, so miserly in parcelling out the seconds it might have been mocking our haste. And it struck me then that something was not quite right. It was as if we weren’t so much a welcoming committee as spectators, ranged around a gladiatorial pit.

I found myself looking at Sophia, wondering if she’d thought of it too. She was the tallest of us, and the prettiest, with only a little coarseness about the thrust of her chin. She was the tidiest, too. There was never a speck on her; specks wouldn’t dare. There was never a stray hair from the curls – golden, natural, curse her – pinned about her head. She hadn’t made room for her little acolyte, I noticed. Her cousin Lucy, thirteen years old, strived to peer over the taller girls’ shoulders, but they were too intent on watching to help her.

I pictured our new teacher walking towards us, all the different versions of her I could imagine: a quiet, gentle creature in need of a friend, feeling her way mouse-like through cold corridors. Or bold and exploring, opening unfamiliar doors, peering into strange rooms until she found a bed she was content to lie in.

The trip-trapping of footsteps approached, as if emerging from my dreams, and we craned for our first glimpse of Mademoiselle Blanc. That wasn’t really her name, but that was how we thought of her then. We were in French class when her existence was announced and so a French name was given; our headmistress, Miss Dawson, favoured French fashions and herself preferred to be called Madame Dumont, claiming this to be in the interest of our education rather than putting on false airs. She said Mademoiselle Blanc possessed all the accomplishments that could possibly be required. She’d even lived in Paris – though we weren’t told why she was no longer there and I’d begun to figure romantic notions for our new teacher: her heart had been broken and she’d returned to heal. Or she’d had to nurse some ailing, ungrateful relative. Surely it must have been some calamity, to bring her here to us.

Below, foreshortened and cast into shadow, came into view a very peculiar figure.

The first thing I noticed was her hair. It wasn’t neatly curled or concealed beneath a bonnet but a disarrayed matted draggle dripping down her back. Her travelling cape was soaked: dark at the shoulders, filthy at the hem. She left a trail of footprints behind her. The maids would be horrified. Madame Dumont was as fond of imaginary servants as anyone but now someone real must be found to scrub the parquet again.

Mademoiselle Blanc turned her gaze upward.

At first, she didn’t seem to take us in. Perhaps her vision was fooled by the shadows hanging in the hall or the darkness of the panelling. Perhaps her eyes hadn’t adjusted from the outdoors, for there was a hectic gleam in them, as if they were full of rain; almost as if she were drowning.

Then her mouth fell open.

Perhaps it is difficult to imagine the effect her appearance had on us. Mademoiselle Blanc was to be our instructress and our guide, to help form our taste and temper. She was to lead us through the tangled thickets of manners and mores, delivering us safely to the promised land of matrimony. Oh, it’s true that schools were expected to do more these days than impart poise and piano-playing, but the accomplishments, for us, were uppermost. We had to catch husbands, after all. Who else would take care of us? Spinster daughters, inconvenient sisters, spare and expensive aunts – none of our relatives wanted that. Worse: we might end up governesses – even schoolmistresses. No: part of Mademoiselle Blanc’s role was to ensure we presented ourselves well at all times, to provide glitter with which to dazzle future husbands, yet here she was creeping into the school like a servant, mud on her boots and reeking of wet wool; not a drawing-room songbird but a half-drowned chick fallen from its nest.

She could see us plainly now. And as we watched her, all of us silent, she shivered. Was that some presentiment – or our unwelcoming faces, or simply the cold? I wanted to believe it was that, for cold she must have been in her wet clothes. For a moment, I shivered with her.

A glassy titter sounded somewhere to my left. A long moment of silence followed, but Sophia’s laughter hung on the air like shattered crystal: something broken that couldn’t be put back together.

Another sound was Lucy, giving an unladylike splutter as the mirth spread. Matilda took up the laughter, and Ruth, and Grace, and it grew, hidden behind hands held to lips. It flew quick as a rumour, relentless as bad news. There were no words. There would be plenty of those later, when we were in our dormitories; then we’d hear them all.

And the shame of it would follow Mademoiselle Blanc, like a shadow. This was worse than standing on a windowsill or bumping one’s head against the glass or having a favourite horse. It would cling to her like mud on her skirts, mud that wouldn’t wash off no matter how she scrubbed.

Mademoiselle Blanc. Even her name seemed part of the joke, meaning white, spotless; pure.

Her gaze darted into each shadowed corner as if seeking a place to hide, but it was no use. She had to glance upward once more, seeing her own fall, her humiliation reflected in our eyes. For a moment, she looked at me. Blood rushed to my cheeks and I tried to smile at her, though it felt more like a grimace on my lips.

‘What do you do there? Idleness!’ Madame Dumont’s voice rang out, tight with barely contained fury. The new arrival spun to face her, as if she were the one being chastised.

‘Girls! Back to your embroidery at once. Miss White, you are most welcome. Pray, this way – step into my study. What an evil day it is!’

If she said anything else, her words were lost. Hurrying away, our stifled laughter broke free, echoing from the walls, the cornices, the sadly besmirched parquet floor. And laughter spilled from me too, though unlike the others, I was not entirely certain why.

* * *

I didn’t go back to my embroidery, never mind what Sophia would say. Sewing was dull and repetitive and I couldn’t see the point in decorating needle-cases or making embroidered circles for china fripperies to stand upon. Instead I sneaked along a quiet corridor, a bare, unpapered, narrow space used by the servants.

The folly was a rather unusual structure. It was only obvious from the outside that its walls curved outward, with each corner softened further by a narrow, circular tower. The impression wasn’t so much of a square as a cylinder, with giant pegs thrust into the earth to pin it in place. It was an oddity, and when seen against the flat vale stretching away all around, might almost have been disconnected from the rest of the world.

From the inside, things appeared more ordinary but felt stranger still. I was sure this corridor curved, following the line of the outer walls, yet it hardly appeared to do so. Instead, it felt subtly distorted; without a window to orientate myself, it was difficult to tell if it was the walls or my own self that was not quite true. I was relieved when I reached the door that opened onto the tower stairway, the building’s south-west ‘peg’. Here was a window: a narrow slit, little more than a loophole, looking out over the outbuildings behind the folly, then fields and copses and villages, the occasional spike of a church jutting from the rest all the way to the horizon.

I still didn’t know if it was Captain or Bard who’d come back. Amid the tight-laced, rule-bound, uniformly dull school, the horses were something beautiful. They didn’t care for deportment or fine speech or etiquette; they were already perfect. I thought of their proud steps, their shuddering muscles, the dark softness of their eyes. What secret thoughts must they keep behind them? I liked to sneak early season apples for them from the gardens. Sometimes I’d rest my head against Captain’s face and feel the bony shifting as his jaw munched – for Bard was too skittish and wouldn’t allow such a thing. But Captain enjoyed my company, standing still and quiet after the apple was gone, lipping at the collar of my cloak.

I loved the good smell of horse. It sent me home in a heartbeat: not to my grandparents’ house, which I’d come to think of as another prison, but farther still, to my parents’ farm. I heard again Mama’s voice, distracted and distant, calling me in for tea; the muffled clump of Papa’s muddy boots on cobbles. And my sister’s laugh – for I was never alone then. There was always another face next to mine, with bright eyes and freckles, the flash of white teeth as she dreamed up some new mischief.

The rasping fssk of Gadling’s brush came clear across the air as I stepped outside and walked towards the stables. The carriage was abandoned in the yard, its harness hanging loose, the shaft pole forming a triangle with the ground. It seemed terribly still, a sharp contrast to the vigour of his brushing. There was anger in the sound and I hesitated. He knew I visited the horses, of course. I didn’t suppose he welcomed such visits; it wasn’t done, not by the people who decided what was done, but I think he recognised in me someone who loved the thing he loved and so he tolerated me.

The top of the stable’s half-door was open, swaying a little in the breeze, since it hadn’t been pinned back. It was Captain’s stable and I hurried my steps, the rhythmic brushing growing louder. I told myself Bard had only thrown a shoe, that I needn’t feel guilty for wishing him gone. Gadling had left him with the farrier and would fetch him later, and I’d bring both of them all the apples they wanted.

Inside the stable, damp glossy curves gave the suggestion of bulk. The smell was of wet hide and musk, more animal somehow than the usual comforting scent of horse. Carrying his head low, the beast swung his neck around to see who had come, revealing the gleaming whites of his eyes.

It took a moment longer to see Gadling. He stood motionless at the animal’s shoulder, glaring at me, the sound of his labour having ceased, though I didn’t know when. I felt every inch of my intrusion, its unexpectedness, its unsuitability, and took a step away in spite of myself. He is a servant, I reminded myself. And I will be a lady.

I didn’t feel like one as he said, ‘You, is it?’

In reply, I held out my hand to the horse. Although I had no apple he expected one, shifting on his haunches and stepping towards me. He thrust his long nose over the door, already searching, lips smearing my sleeve.

‘Captain.’ The name slipped from me, soft and crooning. ‘There you are. You’re all right – you are, aren’t you?’ I leaned in, the slight greasiness of him just brushing my cheek. Then something struck the side of my head, a hard blow with bone behind it, and I found myself sprawling on the cobbles, skirts splayed and crinoline bouncing, clutching handfuls of flaking muck.

‘He’ll not have that. Not that ’un.’ Gadling’s voice was thick with amusement. No: satisfaction.

I scrambled to my feet, grabbing at my crinoline with dirty hands while Gadling stared with dirty eyes. I tried not to think of what he could see – what he’d already seen. Petticoats? More than that? My cheeks flamed. This, I thought, is the reason this is not allowed, and I hated myself for thinking it.

When I’d regained my feet – with no help from Gadling – I stared at the horse that stood in Captain’s stable, looking so much like him and yet not him, not at all. It seemed so obvious now. This horse’s blaze began with a star between his eyes, where the hair formed a little whorl, but unlike Captain’s the white stripe went right down his nose and spread across the soft delicacy of his nostrils. Bard’s markings were finer than Captain’s had ever been and I wanted to weep at the sight of them.

Gadling resumed his work, swiping at the horse’s damp back with a leather. He had to get the sweat off or the beast might catch a chill. Horses were expensive. No groom could allow that.

‘Where is he?’ I asked, though a part of me already knew.

‘Knacker.’

I stepped back before the force of the word, wrapping my arms around myself. There was no amusement in Gadling’s expression now. His face was a wax mask with blank eyes, covering over something else: something I didn’t want to see. If I wasn’t here, I realised, his look would be different. I thought of a snail stripped of its shell; a lamb opening its new eyes for the first time.

Abruptly, he threw down his leather, as if to say, Be damned with it; let him shiver. ‘Her.’ He gestured towards the school. ‘It ’appened when he saw her.’

An image flashed before me: limp and draggled hair, darkened from the rain like an animal’s pelt, dripping onto a parquet floor. As if he could see it too, Bard shifted on his haunches.

‘Spooked at her.’ Gadling spat phlegm into the straw and I wrinkled my nose, more from acquired habit than disgust. ‘Not Captain – he were right enough, just like always. But Bard – one look at her, and that were it. He shot off – dragged Captain right across t’ station yard. Up onto t’ pavement. Tripped, he did. Both his knees gone. Poured with blood. Fucking poured.’

The curse was a cold shock. It was as if he wasn’t really speaking to me at all, as if he’d forgotten I was there.

Gadling ran a hand across his sweat-streaked face. ‘She got a hold of his bridle. Not Bard, he wouldn’t have her. She took a hold of Captain’s cheek-strap and whispered in his ear. Stood there in the rain while he bled. Soaked, she was. Bonnet in the dirt. Didn’t put her hood up to cover her face. But I weren’t fooled.’

He stepped forward, into the light. ‘Bard knows. Horses sense things – they know what they don’t like. Bard knew, but it were Captain who suffered. It were Captain who had to be shot.’

He was crying. I’d never seen anything so shocking. I’d wrung chickens’ necks and seen a calf coming out dead from its mother and watched smoke-grey kittens drowning in a pond, but nothing like this. Gadling was a man. He was grown. He was older than me and strong, someone who went out into the world and earned his bread, and he was crying in front of me, nothing but a girl. He didn’t even seem aware of it.

He was in his shirt-sleeves. Not even that, for they were rolled back to his elbows. I could see the muscles under the skin, his arms browned by the sun. His shirt was soiled, not with foam or sweat from the horse but with blood. My gaze ran down to his belly where the cotton clung to his body. I pictured the blood coursing warm from Captain’s veins, Gadling trying to hold it in, to catch it in his hands as if he could put it back again, undo what had been done.

He saw me looking at him. His expression slowly turned into something else, something I couldn’t read. I wanted to tell him I’d seen worse and more, that it was nothing to me, but I swallowed the words, for how could that help? I backed away then turned and ran from him. As I went I didn’t hear my footsteps or my own rapid breath; only the fssk, fssk of a brush, resuming its work against the hide of a single chestnut horse.