Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

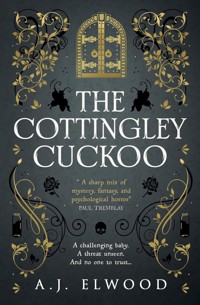

Rosemary's Baby meets Laura Purcell's Bone China in a dark British fairytale… Captivated by books and stories, Rose dreams of a more fulfilled life, away from the confines of the Sunnyside Care Home where she works to support herself and her boyfriend. She hopes the situation will be short term. Charlotte Favell, an elderly resident, takes a strange, sinister interest in Rose, but offers an unexpected glimpse of enchantment. She has a mysterious and aged stack of letters about the Cottingley Fairies, the photographs made famous by Arthur Conan Doyle, but later dismissed as a hoax. The author of the letters insists he has proof that the fairies exist; Rose is eager to learn more, but Charlotte only allows her to read on when she sees fit. Discovering she is unexpectedly pregnant, Rose feels another door to the future has slammed. The letters' content grows more menacing, inexplicable events begin to occur inside her home, and Rose begins to entertain dark thoughts about her baby and its origins. Can this simply be depression? Or is something darker taking root?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 485

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Copyright

Title Page

Leave us a review

Dedication

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Part Two

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Acknowledgements

About the Author

“Lures you in with its charm and cleverness, and then, wow, it knocks you for a loop and leaves your head pleasantly spinning. A sharp mix of mystery, fantasy, and psychological horror that also explores the weight and wages of motherhood.”

Paul Tremblay, author of Survivor Song

“If fairy tales never go out of fashion, it is because of books like this. This is a wonderful tale on magic, poetry, motherhood and, ultimately, us.”

Francesco Dimitri, author of The Book of Hidden Things

“A.J. Elwood has created a seductive tale with a sinister edge, where nothing is quite as it seems. Written with great subtlety and skill – and a good serving of chilling menace – this dark fairy tale is both a study of human obsession and a hymn to the power of storytelling itself – I was captivated.”

Katherine Clements, author of The Coffin Path

“A.J. Elwood’s exquisite, sharply observed prose brings out the eerie in the everyday, and makes the fantastical seem natural.”

Catriona Ward, author of The Last House on Needless Street

“Consistently took my breath away – a sweet but chilling marriage of real life and make-believe, and a beautifully voiced observation that the truths inside us are oftentimes the most difficult to face. Magic realism at its captivating best, I loved every page.”

Rio Youers, author of Lola on Fire

“A marvel. Both sinister and cozy, it reclaims the eeriness of Faerie, and provides lots of comforting shudders along the way. Twist follows twist, the unease maintained right until the last page.”

Marian Womack, author of The Swimmers

“A.J. Elwood is expert at weaving fairy-tale lore with psychological menace; a tale that grips you to the last page.”

Marie O’Regan, author of The Last Ghost and Other Stories and editor of Wonderland and Cursed

“Beautifully written, The Cottingley Cuckoo is a wonderful plaiting together of ancient and modern, at once melancholy and strange. I enjoyed it immensely.”

J.S. Barnes, author of Dracula’s Child

“Reality and folklore weave together so tightly that new mother Rose can barely tell one from the other. A.J. Elwood builds a sense of creeping dread that will keep you breathless to the end.” Angela Slatter, author of the World Fantasy Award-winning

The Bitterwood Bible

“A fairy tale as they’re meant to be, The Cottingley Cuckoo is a masterclass in tension, paranoia, and a rising sense of deep dread. Elwood’s deft characterisation and sharp prose ensures that this whole story feels real, even when fact and fantasy become inextricably entwined.”

Tim Lebbon, author of Eden

“There’s nothing whimsical in A.J. Elwood’s novel that references the Cottingley photos. It’s a modern changeling tale that pulses with the malice of the original fairy lore.”

Priya Sharma, author of All the Fabulous Beasts

“Cleverly merges fairytales and more disquieting folklore, but an even greater triumph is its depiction of the fears and disorientation of the early weeks of parenthood. I loved every moment of this haunting tale of fairies, changelings and delusions.”

Tim Major, author of Hope Island

“A smouldering, suspenseful and gloriously sinister exploration of the old, bad brand of fairies. I loved every word, and the ending had me chilled to the bone.”

Camilla Bruce, author of You Let Me In

“An unsettling Gothic novel which switches effortlessly between a modern setting and the familiar – yet unfamiliar – world of England’s pastoral past. Elwood’s writing is confident, crystal-clear, and deeply evocative; a vein of deep cruelty and ancient horror runs through the book from beginning to nightmarish end. I found it absolutely impossible to put down.”

Ally Wilkes, Horrified Magazine

The Cottingley Cuckoo

Print edition ISBN: 9781789096859

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789096866

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP.

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: April 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

© Alison Littlewood 2021. All Rights Reserved.

Alison Littlewood asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY.

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

For Priya and Mark

1

The first thing I notice about Charlotte Favell is that she smells like my mother. The perfume creeps under the door and into the hall and I recognise it at once: lily of the valley, and I am a child again, balancing in her heels while I dab it behind my ears. It is as sweet as it is familiar, and I wonder that anyone would choose to wear it now. It came as a shock to me to learn, later, that lilies are poisonous.

I go in and she is the first thing I see, sitting with her back to the window so that I have to blink to make her out, and the second thing I notice about her is that she doesn’t smile. Most of the residents had, wanting me to like them or wanting to like me, because they think we might be stuck with each other for long enough. They don’t know that, for me, this is purely temporary.

Charlotte Favell is nothing like them, that’s clear. What she is like I don’t know, not yet. I wonder if I’ll see her smile later, when I serve her dinner or help with her hair, and realise I’m not sure I want to. Maybe such familiarity would mean I belong here; or perhaps my discomfort is something else, something to do with the sharpness of her eyes.

Her spine is very straight. ‘Old school,’ Mandy had said. ‘Manners, talking proper, all that. You’ll get it.’

I wasn’t sure if Mandy was telling the truth even then, but I smile at Mrs Favell anyway. She doesn’t do anything, doesn’t even nod, and for a second I wonder if she’s asleep – sleeping with those piercing eyes open – but she shifts her hands in her lap, a gesture that could be rejection, could be a question, and I know I should say something, introduce myself. Manners, I think, but somehow my voice isn’t there. I can’t seem to look away from her. She’s wearing what I will learn she always wears: a pastel-coloured blouse that looks like silk: a garment I’d have spilled something on in five seconds flat, a neat, plain skirt; and a string of the most lucent pearls I’ve ever seen. Later I’ll find a succession of those blouses in her wardrobe: pink, mauve, lavender, blue and green, all of them soft, delicate, perfect, and smelling of flowers.

They are not a key to her character. It doesn’t matter what Mandy says. I may only have been here a few hours, but I saw the looks when Mrs Favell’s name was mentioned and I knew at once there was something amiss. It’s not that anyone pulled a face or said anything direct – it might have been better if they had – it was more the way they closed up, as if there were things they wanted to say but couldn’t, or wouldn’t, because if they did they might have to go to her room instead of me.

Then Mandy told me that when I settle in I could even be her keyworker, that I should take special care of her.

The others didn’t say anything then either, but I sensed their suppressed laughter, saw their eyes brighten. I wasn’t sure if the flush I felt was entirely down to the temperature in the care home, kept up high to comfort old bones.

‘It’s room ten,’ said Mandy. ‘You go up and say hello and see if she wants anything, while we sort out all the bedpans.’

Making it sound as if they were doing me a favour – that too was a dead giveaway, but I told myself I didn’t care, and they watched as I turned and headed for the stairs. Mandy and the others are a clique, that much is obvious. We went to different schools but I can almost see them smoking in a huddle behind the gym block, bunking off to eat chips, chatting up the same bus drivers and then, somehow, drifting into working at Sunnyside. And they know I’m different. I got the sense they can smell the university on me. I may have only been there a year before I was called back again but I feel marked somehow, and I’d had the urge to tell them; to package up my failure and present it to them like a gift. But my mother’s face had floated before me and I’d said nothing.

And so I went to see what was so wrong with Mrs Favell while Mandy turned and cooed over Edie Dawson, everybody’s favourite. She’d just finished knitting some tiny garment, soft and fluffy and pink.

‘What is it that you want?’

Mrs Favell’s question makes me jump. Somehow I still can’t speak. It isn’t her words or the sharp, clearly incised consonants or her tone that cuts into me but the clarity of it, the bell-like musicality of her voice. It doesn’t sound as if it’s coming entirely from inside this room: enclosed, narrow, almost the same proportions as a student cell in the halls of residence I’d briefly lived in and only a little larger. She has the usual accoutrements: a single bed, though hers is ordinary rather than adjustable or fitted with guard rails; a wing-back chair; and a matching wardrobe and chest of drawers in anodyne blond wood, not a sharp corner in sight. The walls, as in all the rooms I’ve seen, are painted peach, a colour someone must have imagined would look homely but doesn’t. And then, in the middle of it all, these: a gleaming bureau, well used and weathered but polished to a heartwood gleam, as if a corner of an antique shop had materialised here in this room; and above it, her photographs, not a single one in colour.

I realise I’m staring at the pictures. Their ornate silver frames reveal a series of faces: all of them women and children, some of the ladies wearing bonnets. They look stern and impossibly distant, except one: a smiling girl, her eyes full of merriment and dimples in her cheeks, shining curls escaping a hat that places her a hundred years in the past. I suppose she must be long dead. I wonder how Mrs Favell could have known her, if she’d known any of them, or if the photographs are just dressing. That’s the word that comes to me – dressing – and I don’t know why. We’re supposed to talk to the residents about their pictures, their old lives, the manager told me so, but I shiver and look away.

‘Come here,’ she says.

Her tone makes me feel like a child and she isn’t supposed to give me orders, not like that, but I don’t want to start off on the wrong foot and so I smile as if I want nothing more than to go towards her. She holds out one hand like some ladies do in films, palm down, the fingertips hanging limp. I’m not quite sure how to respond but I touch my hand to hers, just for a moment.

‘Charmed,’ she says.

I start to step away from her but she leans towards me and grasps the short sleeve of my tunic, pulling it higher, and I squirm. Her fingers are like iron and just as cold.

‘Painted,’ she says. I don’t know what she means until I realise she has bared my tattoo, the one I’m supposed to keep covered: a garland of briars around a central rose, the thorns long and sharp, all in simple black, no colour in it. At once, I am minded of my mother again, the moment she had first spotted it; her bright fury. I’d sneaked off and had it done on my fifteenth birthday, at a parlour that was none too picky about the law or what her wishes might have been, so eager to be me, to claim my own skin.

Mrs Favell smiles, as if she’s uncovered a treasure. I didn’t admit to being inked when I had my interview here, but ‘No visible tattoos’ was stated in the application pack. It had put me off – what kind of backwater was this? – but then, money’s tight and I couldn’t afford to be put off. Not yet, I think.

‘You love nature?’ Her voice is arch and there’s a flash of impatience or something else in her eyes, amusement perhaps, or maybe she’s wondering why I still haven’t spoken.

At last I find my voice and say, ‘It’s my name. Rose.’

‘Ah.’ She lets out a trill of laughter, letting go of my sleeve. ‘Of course.’

The way she says of course summons an image of Mandy, grinning and pointing at the ceiling at the thought of how I’m getting on.

I straighten my posture, push back my short black hair. ‘I came to see if there’s anything you need.’

‘Did you.’ She doesn’t say it like it’s a question. She stares at me until it becomes uncomfortable. Her eyes are clear as a twenty-year-old’s and very blue. Her skin is a little creased and thin-looking but she carries no spare flesh and the overall impression is one of elegance. I have the idea that she’ll walk with her head high, with poise, that she’ll carry herself better than I do.

‘Any help with the stairs, perhaps?’ The words feel stupid on my lips, particularly since there’s a lift at the far end of the corridor for anyone who needs it, but I want to fill the silence, or offer some reason for my presence, or simply leave.

‘Oh—’ she puts a hand to her mouth to cover a sudden smile, a gesture that seems purely theatrical, and she lets out another trill of laughter.

Be careful, I think to myself, biting back a retort, sensing hidden depths, a polished surface covering something worm-eaten. Another word springs to mind: acerbic. It strikes me that she’s a woman who likes to play games and is likely to be good at them. I do not think she would take well to losing.

‘Yes, you may help me with the stairs, if you wish,’ she says. ‘And later, you shall read to me. You’ll like that, won’t you, Rose? I see that you will.’

She says it as if she really does see, and she’s right. To sit away from the other residents and staff, to be immersed in a book – to share dreams and ideas and something bigger, just for a little while – that is a pleasant picture, an ideal, I suppose, of what I imagined life at Sunnyside might be like. I wonder if it’s common knowledge that I studied Literature, at least for a time. Mrs Favell has a way of looking at me that makes me feel transparent, as if she can read me too.

I reach out, expecting her to take my arm, but she doesn’t. She merely holds out her hand as she did before and places it over mine, as if I were a page and she a queen, and we process down the stairs like that, side by side, our hands held high between us. I don’t quite know how to arrange my features as we enter the residents’ lounge, the clatter of dice and rustle of newspaper and the murmur of conversation all stopping suddenly like the closing of a door. Mandy and Sarah are over by the tea trolley, scowling as if this isn’t what they expected; as if they want me to run from the building screaming or crying. I hold my head higher and glance sidelong at Mrs Favell’s sharp little eyes. Then I turn to meet the world with the most genuine smile I’ve felt on my face in days.

* * *

3rd September 1921

Dear Sir Arthur Conan Doyle,

Forgive the impertinence of my writing to you as a stranger and without introduction. I have lately exchanged correspondence with Mr Edward L. Gardner, and he would have been pleased to be our intermediary; but I felt that in view of your current endeavours, I should not delay in laying before you the wonders it has been my lot to discover.

I am aware that you have unveiled upon the world some photographs in which have been captured, by the agency and innocence of children, the little beings that live all about us and are usually unseen, which we have been pleased to name ‘fairies’. Naturally, Mr Gardner, whom I had heard of through his lectures in Theosophy, hesitated to admit any particulars of your continued interest in the matter to me. I trust that, when I reveal the reason, you will feel his change of heart understandable, and I hope his only sensible course.

I hold within my hand something that will be of the utmost interest to you, if not the crowning exhibit in the proofs it may be your pleasure to unleash upon the disbelieving world. I will come to it; but first I will explain how it came to me, and say that I myself have undergone the most profound change of view regarding the existence of such beings, so that I hope I may be the model of what is to come upon a larger stage.

I am, I should say, too old for fairies. I am indeed the grandfather to a little girl, Harriet, who is seven years old. Sadly, the war visited me with the deepest grief with regards my son – my wife was spared such misfortune, having gone to a better place some years previously. My son’s wife, Charlotte, and his child have done me the honour of abiding with me for the last few years, greatly to my comfort. I gave up my little business in the architectural line soon after the event and moved to a pleasant cottage just outside the village of Cottingley, with which I know you are familiar, for such is where the fairies were apparently captured on a photographic plate.

You may think that such circumstance would mean that Harriet had caught tales of the ‘folk’ from the local children, and it is true that she has heard tell of them, but little more. She is rather younger than Frances Griffiths and much more so than Elsie Wright, the two amateur photographers who brought the sprites to your notice; and being new to the village, she has often been somewhat rebuffed as an ‘incomer’ or ‘offcumden’ by those who should be her playfellows. Furthermore, we have discovered there to be a marked disinclination to speak on the subject of fairies among the residents hereabouts, one which has passed, rather more surprisingly, to their children.

And so it was with much enthusiasm, but nothing in the way of formed notions or expectation, that Harriet persuaded me to go ‘hunting for fairies’ in Cottingley Glen earlier this year.

Wishing to please her, and to allay in some wise the loneliness in her situation at which I have hinted, I set out readily enough. We had been there often before: she enjoys naming the flowers, and arranging pebbles in the stream, and peeking into birds’ nests. It is a pretty place, and hearing her laughter, and her chatter of magical things, is pleasant for a fellow of my more sober years; and I smiled as I went, listening to the babble of Cottingley Beck and child alike.

There is a place – I understand Miss Wright has spoken of it also, though you have not yet found opportunity to visit – where the brook falls in merry little steps into the pools below. All about is verdure, with an abundance of wildflowers and singing birds, and the trees lower their branches as if to provide a resting place for any travellers who wish to pause and admire, and hang their legs over the stream. I did so, being rather more fatigued than Harriet, who busied herself about the water, poking twigs into the hollows to ‘seek them out’.

She soon alarmed me, however, with a shriek, and I looked up sharply to see her whitened face, and a flash of light which I took for a reflection dancing in the water.

Tears started into her eyes. She held up a hand, staring at it, and at first I saw nothing; then a drop of crimson appeared at the knuckle and dripped into the pool. I hurried towards her, thinking she would begin to cry in earnest, but she appeared too surprised to do so. I caught her arm, drawing her up the bank, and examined the wound. Thankfully I found only a small, circular puncture, nothing concerning, and indeed she seemed to have forgotten all about it, for she pulled away and slithered down the bank again. She dirtied her dress as she went, and landed with her feet in the water.

I was rather inclined to scold her, but she stood there with her back to me, so intent on something in her view she did not hear my words. I called her name; she remained motionless. This absence of attention was concerning. She was not accustomed to ignoring her elders or disregarding their imprecations, but since she still did not turn I became curious and stepped towards her.

She was peering at a rock that jutted from the beck where it fell a matter of three or four feet to the pool in which she stood. The outcrop was darkened with spray and dressed with moss, though its upper surface remained relatively dry. There, tiny white flowers wavered in the humidity thrown up by the water. I could not see what had so interested my grandchild. I thought to find there some bee or wasp or other stinging thing, and then I blinked, for where the air was misted I thought I caught sight of a hazy form. It was like the tiny semblance of a man, but so indistinct I was certain I must be mistaken.

I forgot myself so much as to take another step, which soaked me to the ankle, but I did not look away until another bright flash caught my eye. This was to the side, and again could have been nothing but sunlight playing on the water, except that when I looked at it directly I saw six or seven of the brightest, smallest, most lovely of beings, floating about us in the air.

Harriet’s laughter added to the atmosphere of wonder that came over me at the sight. My eyes are not what they once were, but when I peered more intently I made out the most perfect little ladies, their hair like gossamer and their wings iridescent like those of a butterfly. They captured the light and threw it back, now in lavender, now mauve, now blue and green, now in the palest of pinks.

Harriet called to them and stretched out her hands as if to provide a perch for them to land upon, but they did not; they drew away, and instead she began to follow them. The strangeness – nay, the sheer peculiarity of it, the sense of falling into a dream, was such that I reached out and seized her shoulder. And something – oh, I do not know what, but something made me turn from such gorgeous little miracles and back to the grey stone.

I knew not what it was, but I leaned in closer. And I saw a little man all dressed in green, not six inches high. I did not see if he possessed wings like the others, for his expression caught my attention utterly. His pippin face was unreadable, but his eyes, which were quite black – and, if I may say it of such lovely perfection, somewhat soulless – were brilliant with anger, which deepened when he saw me looking at him.

The sight froze me to the spot, and I became conscious of how cold it was, standing with my feet in the pool; but I peered more closely, because I saw that he was not alone. He stood over a little body lying at his feet. It was another of the females – quite beautiful, but entirely motionless.

I could not help myself: I reached out and he leaped into the air with rage, landing once more on the rock in front of the prone figure. Harriet was beside me again and she let out another shriek at his motion but at the sound he seemed to despair, and in the next instant another bright flash marked his darting away. A series of little clicks, such as might be made by a bat, drew my attention towards where the gaily dancing maidens had been, but as if by some mutual consent, they too had passed from sight.

I fully expected his companion to have similarly disappeared, but she had not. She lay as before, indifferent to everything, for I saw that her breast did not move with any breath, nor did any animating principle enliven her features. Her eyes were closed and I could not doubt that she had gone to whatever heaven awaited such creatures.

That was the moment when I realised I could return home not merely with a fanciful tale, but carrying the proof of what I had seen.

With special care, I bore up the tiny form. I hardly felt its weight. I asked Harriet to draw my handkerchief from my pocket and I fashioned a sling in which to carry it, anxious to avoid crushing her wings. I kept expecting the fairy to vanish beneath my coarse hands or to dissolve into ether, but she did not.

I cannot adequately explain the effect it had upon me. My powers of description pale before your own; I will only say that my wondering was matched by a peculiar sense of fear at seeing something that was thus far out of my experience or expectation. I became concerned at how rapidly my heart was beating – I am no longer a young man – and I had an odd aversion to lingering any longer by the beck. Indeed, I wished to be away from it, and the glen, as quickly as was practicable; and so, stealing away the bounty I had found there, I walked home with Harriet by my side, the child piping questions to which I possessed no answers. And I hope it is not too fanciful to say that as I went, the very sky looked different to me, knowing that such creatures live beneath it.

Now, justly, I am sure you would request of me what became of the fairy. This is the point where the observer of such a marvel should say it has indeed vanished into the air, leaving no trace behind, conveniently leaving their story to the credulity of the listener; but such is not the case.

I placed the frail body into a little wooden box. I somehow did not like to have it in the house, though it constantly preyed upon my mind, so I placed it in an outbuilding to which only I possess a key. Was it that I still struggled to encompass the existence of such a thing? Harriet seemed to feel an odd kind of reluctance too, or I think she did; at any rate, she did not like to speak of it. If I tried to begin on the subject, or even if she observed that I was going outside to check on it, she would close up somehow and slip away to bury herself in a book.

I regularly looked in upon the box, though something prevented me from opening it. It was not until a number of weeks afterwards that I felt I should intrude upon her little casket and see what had become of the fairy. I know little of the process of human decomposition, and regardless, I do not suppose it would be directly comparable; but I rather dreaded witnessing the putrefaction of such a lovely thing, and I must confess, the fear had grown upon me that she might really have vanished. If she had, I think there would have been nothing left for me to do but puzzle over the loss of my senses.

She had not vanished. She had putrefied however, and I suspect more rapidly than a human might, but it was not hideous. It was, rather, fascinating in the extreme. Indeed, I examined the body more closely with the aid of a magnifying glass, feeling as if I had fallen into one of your Sherlock Holmes stories and turned detective.

Barely anything was left of her flesh. What remained had greyed and turned powdery, and there was a smell upon bending closely over it, like stale herbs. And beneath the skin – oh, what a splendid little skeleton! It is a wondrous thing, delicate as a bird’s, and easily as weightless. She possesses ribs like a human’s, though more steeply angular, as if crushed by the strictest corset. The leg bones seem very like, though I only noticed upon looking so closely that the knees bend backwards. The arms are similar to a woman’s in everything but size, as is the skull, if a trifle elongated, like some of the more primitive incarnations of humanity. The wings are incredibly fragile, like those of a preserved insect. They are veined and quite whole, the membranes nearly transparent. My hand shakes as I write of it; it is so very strange and wonderful.

And so I come to the purpose of my letter. I have not told of the fairy to anyone save Mr Gardner and now yourself. Indeed, I scarcely know what to do. This evidence could open the eyes of man to something so momentous it is unheard of in our history, and yet I fear I am not possessed of the skills or wherewithal to do it. And so I write to you, Sir Arthur, most humbly, in recognition not only of your penmanship, which is of course without compare (I have read many of your praiseworthy stories, and even now Charlotte sits at my side, barely keeping in check her ardent admiration and good wishes), but also with regard to your high reputation, your unimpeachable character, and your interest in the world I have so unwittingly stumbled upon.

The skeleton, I am certain, will pass any inspection. It may be photographed; it may be examined, so long as such examination does not press it to destruction, for it is as fragile as may be supposed.

In short, I can only assure you what a singular object it is. I would be greatly honoured to set it before you at any date you require, and at your convenience. I am only sorry I cannot send it to you, but as I am certain you will understand, I fear to move her – she would crumble to dust, I think, or may be mislaid upon the way, and that would be the most tragic and unbearable loss.

For this is something that should belong to the whole world. Of course, the mind of man is such that when faced with an idea so new, the inclination is to see what one will and disregard anything that does not line up with it. But this – it must surely break through any such failure to see. It cannot be denied!

Needless to say – and the times are such that I must address a point that should require no assurances – I seek no monetary gain. I would merely see the remains set before those who may use them best for the advancement of Truth and Knowledge, and such things should never be sullied or brought into question by financial inducement.

I have exhausted my tale. Pray, forgive the length of my letter; having remained silent on the subject so long, I am quite carried away by it. I dare hope you will be as excited as I with the discovery, and I most eagerly anticipate your reply.

Your humble servant,

Lawrence H. Fenton

PS. I should add that Harriet’s little hand healed very well; there were no lasting effects. I do not doubt that she scraped it on a stone as she started away in surprise upon seeing her splendid discovery. Truly, in the realm of fairies, children have proved to be our most visionary and bold adventurers.

2

I had thought I would be able to guess at the contents of Mrs Favell’s bookshelf. She would have serious, weighty tomes, something I might have read as part of my degree; peeling linen boards and gilded pages rather than the pink-covered paperbacks they keep downstairs. She’s not the Catherine Cookson or Mills & Boon type.

I hadn’t expected the thing she placed in my hand. It’s a letter, written with fountain pen flourishes on thick cream stock, the ink a little faded, the paper darkened at the edges. Its touch is luxuriant and I’m still half caught up in the magic of the words, though I don’t know what to think of them.

Wherever did she find it? It crosses my mind that it must be valuable, that I should be wearing white cotton gloves – after all, it’s addressed to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. And yet the letter isn’t from Doyle. There’s no sign it was ever delivered to him. And if it really had been in the possession of the author who created Sherlock Holmes, how could Mrs Favell have come by it?

My son’s wife, Charlotte, the letter said. I found the line again: and his child. I wonder if the name is a coincidence. I look at the Charlotte sitting in front of me, her eyes closed yet with an intensity about her that makes me think she’s listening, waiting for my response. I shake my head at the strange idea that comes: that here is the Charlotte spoken of in the letter. But the Charlotte it refers to must be long dead. And she’s a Favell, not a Fenton – meanly, I tell myself I can’t imagine she’s changed it through marriage. Maybe she discovered this in an auction or an antique shop, noticed her own name written there and bought it as a curiosity.

Why ask me to read it to her, here, now? It’s bizarre, but then the whole thing is peculiar, more like the opening to a story than a letter. If Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had ever come into possession of a faked fairy skeleton, no matter how cobbled together, people would have heard of it. Plenty have heard of his involvement with the Cottingley fairies, said to have been caught on camera near Bradford. I went to the National Science and Media Museum there once with my mother, saw the prints and the cameras they’d been produced with. It was famously a hoax: two little girls had painted fairies onto cardboard, cut them out, propped them up using hatpins and taken their pictures as if they were playing with them. It was Doyle’s belief that escalated a children’s game into a situation they could never have anticipated. From what I’d heard, it hadn’t done much for his reputation that he’d trusted them. The fairies never had been anything but trouble.

It occurs to me what my old tutor’s reaction would have been upon seeing this document, something never uncovered before by academia – the studies I might have built around it – and I feel dizzy.

But perhaps Doyle never received this letter, or issued some scathing reply and disregarded it, or returned it to the sender. That might be how Mrs Favell had come by it – did she have some connection to Fenton? Perhaps she’s a distant relative.

I look up and see that she’s opened her eyes. She’s watching me with interest, her gaze steady and unblinking. When I meet her look she doesn’t alter her expression, just goes on glaring until I’m the one to look away.

‘Thank you,’ she says, and holds out her hand for the letter. ‘That will be all.’

I long to question her, to keep hold of it and examine it again, but it’s as if she’s a headmistress requesting my homework and I hand it over.

I hadn’t expected to be so intrigued. I had offered to read to her for a while after my shift ended – there was no time during it, and I hadn’t wanted her to think I’d ignored her request. I suppose what I’d really wanted was for us to be friends. Now she’s dismissing me, without even thanking me, not really. On her lips, ‘thank you’ means ‘you’re done’.

Now I don’t want to leave. I look at the letter she clutches so carelessly and I want to ask her about it – how she obtained it, what it means, whether it’s a real thing that was sent in the post, on a steam train maybe. Had the great man held it in his hands? But perhaps she’ll tell me it’s simply some kind of joke. She might even say that, in some odd moment of imaginative fancy, she wrote it herself.

One look at those cold blue eyes and I know she won’t tell me. I don’t think she needed the letter reading out to her, not really. She doesn’t wear glasses. She doesn’t have macular degeneration, not like Alf Harding downstairs, pottering about with a cane he doesn’t quite know how to use. I don’t know what she does want. Probably to see me at her beck and call, lending her a semblance of power in a world in which she must have little. Or she wants me to be intrigued, to give me a glimpse of something fascinating and strange, bait for her hook, only to snatch it away when I bite.

I decide not to bite. I say, ‘It was my pleasure, Mrs Favell. Sleep well.’

She stands and turns to the window. It is full of that peculiar light they call gloaming, the perfect word for the radiance coming from beyond the edge of the world. I expect her to say something sarcastic about early nights, since it isn’t yet time to sleep, but she doesn’t. She focuses on the trees that lie beyond the garden, their crowns shifting and swaying in some breeze, and her eyes go soft. She almost seems to be listening, but for a moment everything is suspended. I can’t even hear the television downstairs, on permanently too loud, the clink of teapots or rattle of Scrabble tiles in a bag, the traffic outside.

‘I knew you’d like it,’ she says. Her voice has softened and I wonder who she was before she came here, whom she might have had in her life. A husband? Children? There haven’t been any visitors so far and I can’t picture her with anyone, but how would I know?

‘Rose. What kind of Rose, I wonder?’

Alarm crackles through me, a sudden electrical charge, and I wonder what it is about her tone that makes me so overreact.

‘Goodnight, sweet Rose.’ Her voice is neutral once more, cooler, even cold. ‘I shall most certainly see you anon. Pleasant dreams.’

* * *

The car park is almost empty. The staff ratio is lower at night and most of the others who work days, as well as any visitors, have already gone. The light is almost gone too, having drained from the world while I fetched my bag and put on my coat. When I start the engine, my car’s headlights highlight a patch of hedge, each tiny leaf casting its own black shadow. For a second I imagine diminutive figures dancing in its depths, peering out with eyes that are too dark and blank, and I don’t know whether to laugh or shudder. I try for a smile but that little patch of light somehow makes me feel alone and it quickly fades.

I sense the depths of the woods at the back of the building, the fields stretching away beyond them. But I am headed the other way, through the indifferent town with its hard roads, houses full of strangers balancing meals on their knees while their televisions flicker. I remind myself of the future and suddenly I can’t wait to get home. I picture Paul in the doorway, grinning at me. The two of us huddled up on our sagging sofa while I tell him stories: how one day, we’ll have a big house made almost entirely of glass, with a swimming pool in the garden and a view of the sea. Or an old farm in France, with sunshine every day and goats for fresh milk. Or my favourite: a house in a forest, a turret reaching up amid the branches, a circular room lined with shelves where I’ll keep my mother’s books.

I can almost hear his voice, his stubble tickling against my cheek: You know what’s different about you, Rose? What I love about you?

I never answer. He does that himself, and his answer varies, but his meaning never does. Sometimes he uses the word dreams, or perhaps visions, but mostly he says: You believe.

And I do. Someday we’ll be out of here. I almost made it once and I will again. I remember Mrs Favell, her failure to smile. Is she the only one who recognises the truth – that this is temporary for me? That I’d sat there in my interview and told the manager all the words she wanted to hear, so that I can earn the money to get out? Yes, I’d relish the chance to support the residents. I’d love to work in a caring environment – I really do care. I’m sure I’d fit in at Sunnyside.

But who would stay here if they didn’t have to?

For now, I do have to. I imagine Mrs Favell’s sneer at the sight of our tiny terraced house; at Paul, with his long hair and arms more tattooed than mine; his irregular work, helping a mate shift unwanted furniture or labouring on building sites. Her disdain would surely make me hate her after all. We’re doing okay. At least I got off my backside and found gainful employment. Paul may not be all that driven, not yet – steady jobs never ran in his family – but I reckon that, with a little time and my influence, he’ll change.

I think of the other girls. I bet Mandy isn’t fretting over what she’s done today or what so-and-so said or what anyone thinks of her. She’s probably bitching about the new girl, laughing about how we’d marched down the stairs together, Mrs Favell and I hand in hand like film stars going in search of champagne and finding only bowls of Weetabix. I grin and feel better. Sod Mandy. She’s probably never believed in anything in her life. I picture her fifty years from now, still at Sunnyside, still doing all the same things, until finally she gets old and simply moves in.

I let out a huff of laughter as I turn into our street and see the light shining from our front room. Before I’ve braked fully to a stop the door opens and Paul spills out, his shaggy hair loose to his shoulders, his arms dark with tattoos and strong as a wrestler’s – and I see that his hands are full of flowers, bright points of colour plucked from our sorry patch of garden.

He waits while I park our ancient and battered Fiesta between the van belonging to the painter and decorator next door and a shiny saloon that probably belongs to someone just passing through. He opens the car door for me, all gallant, and I jump out and there are kisses and he puts the flowers into my hands. There’s the big massy head of a hydrangea alongside limp daffodils and sagging tulips, a frayed stalk of ragwort nestled among the rest, all the petals drooping and damp and smelling faintly of petrol. I tell him I love them.

As soon as I’ve put them in a vase and Paul’s throwing dinner together, I go and sit halfway up our narrow flight of stairs, which is narrowed further by the books stacked along the side of each tread. There’s no space in our house for bookshelves, not yet. I run my hands over the worn and battered spines, pushing aside the guilt I’d felt earlier, the memory of my mother’s anger about my tattoo. These are the things we had shared; the books Mum had loved, the ones she introduced me to the moment I could read them. All of the dreams, the visions, are still here: orange-clad paperbacks, black-trimmed classics, tiny volumes of poetry almost lost among the rest.

Mum did most of her dying when I was away, in silence and in secret. She had so wanted me to be free.

But her books remain. I lean against their spines and close my eyes. When I was tiny, I would curl up on her knee while she read fairy tales to me, the first stories we shared together, that were ours. Even before I open my eyes again to scan the titles, as I have so many times, I know I will not find any fairy tales at all and I wonder again where they have gone. Did they vanish into the air? Were they somehow stolen from me? Was the memory even true, or only a sweet fiction I tell myself? Of all the possibilities, the one I can least believe is that she would have thrown those stories away.

I remember that, now, I am to read to Mrs Favell. How very odd that she and I will be the ones to share stories together.

But then, don’t they call old age a second childhood?

3

It feels like I’ve been at Sunnyside forever as I undo the buttons on Reenie Oram’s cardigan and re-fasten them. She’d made a good effort but matched them with the wrong holes, bunching it up in front of her. The manager pointed it out, telling me to straighten it before visiting time, concerned about who might see, what conclusions they would draw. It’s better than the mop-and-bucket duty I’ve spent all morning doing, a consequence of being the new girl.

When I finish I smile, knowing that Reenie will keep staring into space with her pale and watery eyes, and she does, but it seems important to smile anyway. There are flashes that make me think her mind is still working: a sudden glance, a grasp at my hand. I wonder what she’s seeing now. Family? Times gone by? Whatever it is, she keeps it locked inside.

There’s another of the carers going about the residents’ lounge, straightening the mismatched chairs with their wing backs and high seats and plastic covers, setting a walking frame neatly aside, drawing back the vertical blinds from the French windows to brighten the room. Nisha has been here a while. She’s not entirely one of the clique and has a bright smile and a readiness to laugh that makes everything a bit lighter. She doesn’t seem to feel the weight of the manager’s frown or the atmosphere hanging in the air like an exhalation of this place: the sense of giving up, of loneliness that is never really dispersed by the false enthusiasm of let’s-try-to-keep-interested or let’s-play-a-game.

Nisha is admiring Edie’s knitting, held out in her shaking hands. White wool shines in the sunlight streaming in, bright and clean as innocence. I imagine soft new skin, tender little feet kicking, tiny hands enclosed by that softness. I’m glad Paul can’t see my thoughts. The first time he mentioned kids, I laughed; I honestly thought he was joking. We’re not in that place yet. We need the house first, we need to see what lies across the ocean or through the forest or on the other side of the world. We need to see it all.

‘She never visits,’ Nisha says at my shoulder, and I jump. At first I don’t know what she means and she nods towards Edie. ‘She knits herself senseless – see her knuckles? Arthritis. It must be so painful for her. She keeps saying her daughter’s having a baby, like she’s forgotten the kid must be years old now, because she’s never seen it. They live in Australia. They never have been back.’

I look again at the snowy whiteness falling from Edie’s hands. ‘What does she do with it all? Does she post the clothes to her?’

Nisha pulls a face. ‘Too expensive. She gives everything to the staff, whether they’ve got kids or not. You’ll probably get something at some point. Most of it goes through the local Oxfam, I expect. She might as well unravel it and start again.’

I feel a stab of alarm at what Paul would say if I turned up at home with a pair of bootees, then Nisha flicks her eyes towards the stairs and says, ‘Has she given you anything?’

She doesn’t say whom, but I know at once. Mrs Favell doesn’t like to come down in a morning, not unless she’s going out for a walk. Sometimes she doesn’t have breakfast; she eats an apple in her room and then reads, away from the overly loud television, which is currently belting out some inane morning show. She’s not that dependent. She needs less support than anyone here. It was as I suspected, she never did need me to read to her, and I still haven’t worked out why she asked me. To have a look at the new girl I suppose, the fresh blood, new meat. It’s a pity in a way, because I long to hold that letter in my hands again, to touch something from a world so completely removed from this.

I shake my head, though there’s something about the way Nisha asked the question I can’t let go. ‘Why?’ I ask. ‘Is she likely to?’

I regret my form of words at once. It makes me sound like a gold-digger waiting for gifts, but she doesn’t seem to notice.

Leaning towards me, she lowers her voice. ‘The girl who was here before you – there was a lot of trouble. Just be careful.’

I want to ask what happened but just then the manager, Patricia Stott, comes in, and we start tidying away the piles of magazines and disarrayed board games, making space to put out tea trays when visitors arrive. Patricia is a stout woman of fifty or so, her eyes veined with tiredness but still vital, still darting about with swift certainty. One of the residents told me that over the years she’s had two husbands, four children and a whole pack of rescue dogs, and I imagine her organising them all with the same brusque efficiency. She glances at me, checking I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing, and sets down the pills she’s carrying, already sorted and labelled with names and room numbers. Nisha hurries off to help distribute them, making sure everyone has cups of orange juice to wash them down. She casts a sharp look over her shoulder at me – bidding me to secrecy, or something else?

I realise that Mrs Favell has come in. She stands in the doorway surveying the room, pearls gleaming at her neck. Her hair, like Patricia’s, is swept into a bun, but unlike Patricia’s there are no stray hairs floating about her face. She’s holding a book, though it’s tiny and I only notice it when the gold foiled edges flash back the light.

It’s obvious that something sets her apart. There’s no sense of distraction about her, no staring into space, not a moment’s vagueness. I wonder again that she needs to be here, just as her gaze lights on me and she beckons.

‘A walk,’ she says as I approach. ‘Fresh air. Just the ticket, yes?’ She gestures towards the French windows with her book, which I see is old, no name visible on its black leather cover. She tucks it away in one hand and reaches for me with the other, her fingers slender, gripping my upper arm tightly. I should be starting on the teas but Patricia doesn’t object so I don’t either.

I’m not sure if I’m supporting her or being led as we step onto the path that edges the building. A bird trills, high and out of sight, and the world is suddenly sharp slices of sunshine and shade. The garden isn’t that large – Sunnyside’s not purpose-built and it’s clear from the mismatched brickwork that it’s been extended a couple of times, encroaching on the lawns to make room for more residents on the ground floor. There are still plenty of benches dotted around. I half expect to see little plaques set into them marking the death of someone’s aunt or grandmother, like in the park, though I suppose no one wants to think about such things here. There’s a nip in the air, the faint memory of winter, pricking the hairs along my arm. Mrs Favell doesn’t seem troubled by it. She stops suddenly, standing in shadow, only the tip of her shoe crossing into sunlight. She closes her eyes and breathes in, long and deep.

‘Are you all ri—’ I begin, but her grip tightens and I fall silent.

‘Do you hear that?’ she says.

I try to listen. From somewhere comes a child’s brief shout. A distant engine starts up and a door closes. Closer still are the television’s meaningless prattle and a guffaw of laughter – that’s Jimmy Rees, one of the jollier old men. He calls me ‘flower’ and I thought it was because of my name before I realised he calls everyone that, including the postman.

‘That’s a skylark,’ she says, ‘and the wrens are nesting in the azaleas. Caterpillars are eating the leaves. Do you hear them?’ There’s an almost dreamy look on her face, though her eyes remain closed.

Surprise – even alarm – jolts through me. Is this why she’s at Sunnyside? No one’s told me she’s losing her faculties, but maybe it’s true. How can she expect to hear caterpillars? It isn’t possible, but her focus remains, her posture rigid, her expression serious. I actually find myself listening, looking up at the sky, but I see only contrails, the ghosts of other people’s journeys. I can’t see the bird, not now. I can’t even hear it.

When I look back at her, she’s waiting for me. Her lips are pressed into a line so thin they’ve almost vanished, her cheeks sucked inward, her eyes filled with as much amusement as contempt. She holds something out: her book. I reach for it, thinking she wants me to read to her again – no letter this time, more’s the pity – and she says, ‘This is for you. A gift.’

‘Oh,’ I say, drawing back from her. ‘I couldn’t.’

‘You will,’ she says. ‘It’s an important poem. I want you to read it.’

‘Well, I’ll read it to you now,’ I say, gesturing towards a seat. ‘Then we can pop it back in your room. It’s a lovely book.’

‘Of course it is. That’s not the point. It’s for you.’ She thrusts it towards me again and I hear the echo of Nisha’s voice. The girl who was here before you – there was a lot of trouble. Just be careful.

‘I really can’t.’

‘You remind me of me, Rose.’

I start. What can she possibly mean by that? How can she compare the two of us? I’m nothing like her. I realise she’s gripping my arm just around my tattoo, as if to underline the difference between us. I try to keep my distaste from showing and instead answer her earlier question again. ‘I don’t think it’s allowed. I’m new here, you see.’

She gives an amused tsk, as if to say, Do you think I could have forgotten?

‘No such rule. Oh, for heaven’s sake – read it to me then.’ She marches to one of the benches and sits primly, crossing her legs at the ankles. I wonder if she went to one of those schools, back in the day – finishing schools or etiquette, establishments for young ladies, something like that. She nods at the space beside her and I lower myself into it, wondering what exactly happened to the girl before me.