5,98 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

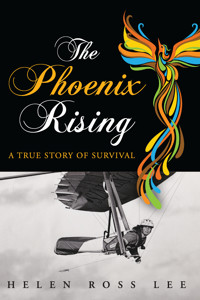

Helen Ross Lee's memoir The Phoenix Rising shows us a successful nurse, mum, and hang gliding champion at the top of her game. In 2008, she suffered a tragic accident in a practice takeoff maneuver that resulted in a grievous traumatic brain injury (TBI), which precipitated a coma and temporary amnesia. Helen refused to give up or give in, regardless of the gloomy prognosis from medical experts. Her ten-year struggle to rehabilitate and return to work (with the support of her family) will inspire anyone who has experienced or cared for someone with stroke, TBI, and other long term chronic illness.

"The Phoenix Rising is an original and bold addition to a growing number of memoirs by survivors of TBI. Shedding light on the TBI epidemic across the globe, Australian writer Lee guides readers from her days as a dedicated nurse, mother, wife, and adventurous hang glider pilot, and down into continual torment that is life and recovery from TBI--her honesty is stunning in detail."

--Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal, TBI survivor, author of 101 Tips for Recovering from Traumatic Brain Injury

"Go, Helen! You deserve all the recognition possible. Your book details an amazing fight for life and an incredible will to live that life to the fullest."

--Barbara Proudman, editor, Tamborine Times, Queensland

"The Phoenix Rising is an ideal read for all people whom have been told that recovery is impossible, that hard work will not pay off, and that life with a acquired brain injury cannot be fruitful. Moreover, this book is a unique inspirational story from which all will draw strength and motivation to use in our individual lives."

--Travis Docherty, MPhty, B Ex Sc, assistant professor, Bond University, director of Allied Health Services Australia

"It is a privilege to know you, Helen, and your story is worth telling the world about and sharing! Your determination will no doubt inspire others to never, ever give up! I thank you for not holding back and sharing intimate details of your life with the reader. I am so honoured to know the writer in person and to have been able to follow her amazing recovery over the years. You and your book are truly inspirational."

--Michaela Kloeckner, ceramic artist, Gold Coast Potters Association

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 449

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Praise for The Phoenix Rising

I would like to add my endorsement to that of Professor Niels Birbaumer’s, having just finished reading the whole of Helen's manuscript. Whilst Helen’s rehabilitation continues to be an ongoing process, small steps eventually amount to a full staircase, and, in Helen’s circumstance, a more independent and proactive life. This book is an ideal read for all people whom have been told that recovery is impossible, hard work will not pay off, and life with an acquired brain injury cannot be fruitful. Moreover, this book is a unique, inspirational story from which all will draw strength and motivation to use in our individual lives. I highly recommend the read.

—Travis Docherty, MPhty, B Ex Sc, assistant professor, Bond University director of Allied Health Services Australia, Rehabilitation At Home, Physiotherapy Rehabilitation Services, and Paediatric Centre, Gold Coast

It is a privilege to know you, Helen, and your story is worth telling the world about and sharing! I have been so excited to finally hold your book in my hands and to be able to read about your life and your experiences. Your determination will no doubt inspire others to never, ever give up! Your book is basically in three parts: before the accident, the accident, and your recovery, and I thank you for not holding back and sharing intimate details of your life with the reader. I also enjoyed the photographs that accompany your prolific writing. This book is very special, and I am so honoured to know the writer - you, Helen - in person and to have been able to follow your amazing recovery over the years. You and your book are truly inspirational.

—Michaela Kloeckner, ceramic artist, Gold Coast Potters Association

Go, Helen! You deserve all the recognition possible. An amazing fight for life and an incredible will to live that life to the fullest.

—Barbara Proudman, editor, Tamborine Times, Queensland

The Phoenix Rising: A True Story of Survival by Helen Ross Lee, is an original and bold addition to a growing number of memoirs by survivors of severe traumatic brain injury, or TBI. Shedding light on the TBI epidemic across the globe, Australian writer Lee guides readers from her days as a dedicated nurse, mother, wife, and adventurous hang glider pilot, through several relationships and marriages, and down into continual torment that is life and recovery from TBI - her honesty is stunning in detail. Her Australian idioms (“one sandwich short of a picnic”) add to her fluid writing. As a fellow survivor, I relate easily to Lee’s loss of the ability to cry, her vision difficulties, and her hatred of “lack of privacy” as she relies on “carers” to shave her legs and her tenacious and daring attempts to try all means possible to alleviate the smaller yet irritating symptoms (eye patches, incontinence) following damage to the brain. Lee’s relentless sojourn through Australian healthcare organizations will remind Americans that our nation often lacks funding for the severely disabled. Lee, however, ends with a bid for “hope” and “optimism” for all sufferers of debilitating conditions. This is a “must read” for those with TBI who wish to learn more of vitamin therapy, mindfulness, acupuncture, neuroplasticity, brain training – and the truth that myriad character traits (courage, stubbornness, the desire to taste coffee) can and do survive severe TBI.

—Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal, TBI survivor, author of Lost In My Mind and 101 Tips for Recovering from Traumatic Brain Injury

The Phoenix Rising:

A True Story of Survival

Helen Ross Lee

Foreword by Niels Birbaumer, M.D.

Modern History Press

Ann Arbor, MI

The Phoenix Rising: A True Story of Survival

Copyright © 2020 by Helen Ross Lee. All Rights Reserved

Foreword by Niels Birbaumer, M.D.

Learn more at www.ThePhoenixRising.com.au

ISBN 978-1-61599-493-9 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61599-494-6 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-61599-495-3 eBook

Cataloging-in-Publication information available at the Library of Congress.

Published by

Modern History Press

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI 48105

www.ModernHistoryPress.com

Tollfree USA/CAN 888-761-6268

International 734-417-4266

Fax 734-663-6861

Contents

Foreword by Niels Birbaumer

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

Dedication

Hang-Gliding Competition Achievements

Prologue

Part I: The Woman I Was

Chapter 1 – Wings

Chapter 2 – Catching Momentum

Chapter 3 – The Updraught

Chapter 4 – A Change in the Wind

Chapter 5 – A Twist in the Line

Chapter 6 – Plummet

Part II: Who I Became

Chapter 7 – Clipped

Chapter 8 – Wings of a Different Feather

Chapter 9 – Home Beacon

Chapter 10 – A Storm of Change

Chapter 11 – A Series of Corrections

Chapter 12 – Turbulence

Chapter 13 – Another Updraught

Chapter 14 – Sweeping Descent

Chapter 15 – Grounded

Chapter 16 – To Walk

Chapter 17 – Fall Away

Chapter 18 – And Again

Chapter 19 – Beyond Me

Table of Figures

Bibliography

About the Author

Index

Foreword

Helen embodies the exact principles which I have been researching and studying for the past fifty years. What she has been able to achieve, is fantastic! Helen ought to inspire everybody. Certainly, anybody who has suffered a brain injury or a stroke should hear her story. After reading this entire book, people will be left shaking their heads in awe of one woman’s incredible determination and strength. It can be said, that brilliance is ten percent nature and ninety percent effort. Helen is too humble to accept the word ‘brilliance’ to be applied to her, but Helen is certainly one bright little star! This is one lady to put on your ‘watch-list’! She certainly knows about survival.

Professor Niels Birbaumer, Senior Professor of Behavioral Neurobiology and Medical Psychology. author of Your Brain Knows More Than You Think: The New Frontiers of Neuroplasticity.

Author’s Note

This is the story of my survival. I still am surviving. I suspect that the acceptance of the credibility of my ‘story’ may be a challenging endeavour. I have attempted to enhance your comprehension, to the best of my literary agility.

Plenty of people keep trying to tell me that either they have experienced a ‘miracle’ or my experiences are the result of a ‘miracle’. It is reasonable to expect that people would clutch at straws if they are desperate however my time for clutching at straws is over.

I am quite willing to accept my physical disabilities. But cognitively, now that’s entirely different. Neuroplasticity involves plain old hard work!

Some people claimed to have the gift of healing. One person even attempted to weave her ‘magic’ on me at the kid’s school years ago! Jesus performed a number of miraculous healings. And these people thought they could perform the same feats as Jesus? Pulease!

With perseverance and determination alone, I have experienced the sort of cognitive recovery, for which the human brain has been designed. And so could any other brain damaged person, who put the effort into re-training their brain.

Humans have been created with a brain which is capable of re-net-working itself, following injury. Let’s not get into fundamental questions about life here! This book may simply provide hope to the millions of people world-wide, who have or are going to experience traumatic brain injury, every year in the world. The World Health Organisation estimates that up to 3.6 million people will incur moderate or severe TBI each year, while up to 60 million people sustain mild brain injury due to an external force, such as a bump or blow to the head. Falls, motor vehicle accidents, assaults, strokes… don’t be in denial. My ‘story’ could be you one day!

For me, life was, and is, exceptionally busy, complicated and confusing, so let me share some of myexperiences with you. I haven’t included everything that happened to me, as some things are best left unsaid. I have also changed the names of many of the people I refer to in this book to protect their privacy. Any real names that appear are included with the permission of those involved, or where there is no threat to their being there is impending.

Some people, after reading my book may remember past events differently.

People often perceive events differently. People perceive events which occur in their lives through the spectrum of what has influenced their attitudes and perceptions previously. Which is why one person will find an experience enjoyable, while another person will find the same experience challenging. I have often commented, “Walk a day in my shoes, would you?” That is why I have written my book.

It seemed to me, that everyone would be held to account one day, as to their attitude, their behaviour and their heart conditions.

This memoir gives all people, the opportunity to ‘walk a day in my shoes.’

I hope to leave every single one of my readers with a sense of hope for the future and an increase in their tolerance for their fellow man, irrespective of the challenges they’re facing. We are all just surviving on this planet together.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge some specific people who helped me along the way, or helped me to see the value of my story.

Glenn Parsons, a long-time acquaintance of mine from the Corryong district in Victoria, was one of the first people to encourage me to write my story. In late 2012, when he first heard about my accident and journey towards recovery, he said he found the whole thing overwhelming.

One of Wayne’s (my current husband’s) clients and a university lecturer on literature development, read one of my early manuscript drafts and felt that it still needed a significant amount of professional editing if I wanted to publish traditionally. At that stage, I was still ‘financially disabled’ however and I was only able to re-edit it myself. It was then I decided to sell my beautiful home, which I’d spent the past nine years struggling to hang onto. This enabled me to have my manuscript professionally edited to then submit it to a selection of traditional publishers.

I also want to thank my husband, Wayne Lee, who put up with a lot during the eleven years it took to ‘research’, write and edit my manuscript.

Finally, thanks also to the many other people who helped and encouraged me along the way.

Dedication

Firstly, this book is dedicated to the all the hard workers in this world. (You know who you are.)

I would also like to dedicate my story to all healers and especially to the many people who helped me on the journey to heal my mind and body.

Hang-Gliding Competition Achievements

1990 Australian Women’s Championships Encouragement Award

1990 Australian Women’s Championships Most Outstanding flight

1990 Corryong Cup 9th overall

1991 Kossen Women’s Worlds 8th overall

1991 Australian Women’s Open 1st place

1992 Bogong Cup Highest placed female

1992 Eungulla Women’s 1st place

1992 Bogong Cup C grade 1st

1992 Australian Open 1st Placed Woman

1992 SE Queensland Women’s Champion 1st place

1992 Japan pre-worlds

1993 Australian Women’s Open 2nd place

1993 Bogong Cup B grade 3rd place

1993 Flatlands B grade 2nd place

1993 Women’s Worlds Japan

1995 Women’s Worlds Chelan USA

1997 Women’s Worlds Mt Buffalo, Australia

Prologue

May 4, 2008

The first day I remember with any clarity, following my hang-gliding accident, was 37 days after I regained consciousness. Prior to that, everything is a bit of a blur, no sense of time, no dreams of any sort. This was the day I was transferred from intensive care into the brain injury rehabilitation unit. I have no memory of my time in intensive care at all.

But on this day, this first day I remember, I sat slumped in a wheelchair, watching my mother folding my clothes. As she tried to organise the chaotic environment of my new ‘home’, I was busy trying to organise the chaotic confines of my own head.

I knew something really bizarre was going on. It was like a bad dream. I felt trapped in my own body. My arms and legs would not work properly. My mouth was dry. I couldn’t understand what was happening to me or where I was.

All of this was a silent crisis within. I hadn’t uttered a sound, unable to find the technical ability to form words. But when I heard a familiar voice from the doorway behind my mother, I jerked upright in the chair, so I would be able to catch a glimpse of the man who so easily evoked such strong memories within me. I was distracted by the impression of the colour red; I couldn’t see the familiar face I’d been expecting, because my vision was blurry and strange. I still didn’t know where I was or how I’d come to be there. But I knew him.

PART I:

THE WOMAN I WAS

1

Wings

In 1984, at the age of twenty-three, I was standing at the kitchen window of the flat I shared with my long-time friend Carolyn French (pseudonym), when I saw a hang-glider as it soared backwards and forwards along the nearby coastal cliffs of Newcastle’s Strzelecki Lookout. I was captivated. I felt such a strong desire to experience such a flight, to look upon the world as a bird would, that I encouraged Carolyn to come with me immediately to find out how. We jumped into my car and drove to the nearby hang-glider launch site overlooking the ocean in the suburb of Merewether. Neither of us had been to a launch site before.

Walking down to what we assumed was the take-off area, I spotted a guy holding a walkie-talkie. It was obvious he was giving instructions to an inexperienced pilot who we could see flying not far from where we were. Tentatively approaching the guy with the walkie-talkie, I asked, ‘Hey, are you an instructor?’

That was how I met my first husband.

~ ~ ~

Paul (pseudonym) was only slightly older than I was. He was good looking and he exuded confidence. I was immediately attracted to him. And whether it was because of him, or because I’d just chased a whim and felt alive with the thrill of it, I felt like something magical was about to happen, that my life would never be the same again. And I was right.

In response to my question about learning to fly, Paul said he taught small groups of students and I was invited to join a new group scheduled to start training in a few weeks. My initial lessons were conducted at various coastal sites. First, Paul took us to low sand dunes where we learned to assemble a glider, connect a harness to it (that supported the pilot’s body), lift the glider off the ground with its weight across our shoulders, and run a short distance with a person running on each side holding one of the wires that held the glider together. The idea was to start low and slow and gradually increase the height of the sand dune that you glided from as you gained control and confidence. I experienced my first very short, very low flight this way. I was terrified, and enthralled.

Physically, it was quite demanding. I needed to lift the 35kg hang-glider, balance it across my shoulders, begin to walk, and then progressively increase the pace to a run down the sand hill. If that wasn’t hard enough, I also had to make constant corrective movements to keep the glider’s wings horizontal while running into the wind. You always launch into the wind.

The glider is controlled by moving your weight in relation to the glider. You are suspended from a point in the middle of the glider and hold on to an equilateral triangle of aluminium tube, with the bottom tube horizontally in front of you. This is called the ‘base-bar’. When first lifting the glider off the ground, the top apex of the triangle rests just behind the pilot’s neck and across the shoulders, with the pilot holding the two downward tubes connecting at the apex. When a certain speed is reached, relative to the wind, the glider can begin to support its own weight and lift off the pilot’s shoulders. Then it lifts the pilot’s weight off the ground because the harness (that the pilot is in) is connected to the glider. The student pilot, all going well, glides to the base of the sand dune, bringing the wing to a controlled halt by suddenly flaring the nose of the glider up (inducing a stall), by pushing the aluminium tubes forward and upwards. Ideally, you land gently on your feet.

I displayed many undignified and demoralising ‘crash’ landings as I slowly learned to get some control of this heavy and awkward contraption. It took many mouthfuls of sand during my outrageous landings to establish some cause and effect relationships in my brain based on when and how I moved my weight in relation to the glider. But my routine humiliation and bruises did not deter me from my ambition of learning to fly, and Paul and my fellow students were always patient and supportive. Even still, Paul wasn’t there when I had my first decent flight. That privilege fell to a nervous assistant instructor.

With the combination of a steady sea breeze blowing straight into the sand dune and then up and over, it created just the updraught I needed to stay airborne. I soon had enough control to get the glider to do more-or-less what I wanted; I was able to glide backwards and forwards above the sand. It was terrifying and addictive. It was wonderful.

From there my class progressed to the most popular Newcastle hang-gliding site: an overlook onto Burwood Beach in the suburb of Merewether. Most Newcastle hang-gliding pilots flew there regularly. It was a large hill facing south towards the ocean, with enough cleared space to assemble gliders. Importantly, if you ‘bombed out’ (could not stay airborne for some reason) there was a sandy beach below, which was mostly deserted because of the sewerage works nearby. Experienced pilots could get high enough at Merewether to fly north along the coast for a few kilometres, picking up lifts from sand dunes, buildings and cliffs. It was at Merewether that I witnessed one of my fellow students break his leg when he hit some rocks near the launch site. He was a big, strong looking lad, which certainly gave me cause to reconsider what I was doing.

But I only hesitated for a moment. Flying a hang-glider felt as natural to me as writing with my left hand had, and I knew not to fight it. After all, my kindergarten teacher had tried again and again to persuade me to move my pencil from my left hand to my right when writing and drawing. It never stuck. And just like with that pencil, I knew that persevering with learning to hang-glide was what felt ‘natural’ to me and I wanted to do. I went on to spend hours soaring back and forth along the Merewether cliffs. Then, with more experience, I was able to fly northwards along the coast to the next beach, and then on to Strzelecki Lookout, which had a sheer cliff-face. Late one summer afternoon, as I flew at the lookout, I looked out over the ocean as the sun was beginning to set in the west. Then a full moon rose out of the eastern horizon. I calmly watched a scramble at the launch site below me as pilots quickly prepared to launch their gliders into such a spectacular evening. As the darkening sky filled with the shapes of poorly illuminated hang-gliders, I slipped southwards for the landing area at an oval opposite Bar Beach and peacefully took it all in. Little did I know that it would be at this same lookout that Paul would later propose to me.

~ ~ ~

Paul made his first move on me at a party held at his house. We had flirted on occasions before the party, but only enough for me to establish that he might be interested in me – and I’d tried to make it clear the feeling was mutual. That evening, Paul invited me out for dinner and it developed from there.

We’d been dating for just a few months before he took me to Strzelecki Lookout and proposed. I said yes without any hesitation; I loved him more than any other guy I’d dated. I was so sure of it.

And I wanted it to be right. Paul made me feel the safest and most secure I’d felt with any other man. He was the most special, reliable, caring, loving, protective and dependable man I had ever met. When he proposed to me, I thought there would surely be no other man in this world who I could rely on to care for my heart better and share in my love of flying as well.

We could talk for hours about hang-gliding, and went out flying as frequently as possible – whether it was in the afternoon, after work, early mornings or weekends, it didn’t matter. We were prepared to travel, making trips to inland sites either alone or with small numbers of hang-gliding friends. We travelled wherever we needed to go in order to gain as diverse a flying experience as possible, in order to develop our skills. It fed my need for adventure and excitement. And I respected how gracious and focused he was. Plus, we had great sexual chemistry. What can I say? I was twenty-four and Paul was twenty-eight. I was a newly qualified Registered General Nurse who was ready to go anywhere, and he was adventure hungry and seemed to have just as much energy and drive as me.

We set about making the arrangements for our wedding pretty much immediately. The hospital where I’d been working had a chaplain whom I’d established a good working relationship with and he agreed to do the ceremony. There was an adorable church in historic Morpeth just up the Hunter River from Newcastle, and my father was happy to walk me down the aisle to my waiting beau. My two sisters were present as bridesmaids and Paul’s daughter from a previous relationship was our beautiful flower girl. Looking into Paul’s soft brown eyes, I was certain that we would be together forever, as we vowed to be on that day. My heart felt as fresh and unblemished as the flowers that adorned my hair, but perhaps I should have known that hearts don’t just reset themselves because you’re feeling happy.

Helen and Paul on their wedding day with Cathy, one of Helen’s nursing friends

I’d never been very good at being in a relationship. When I started high school, I experienced one of the most baffling episodes of my life so far. At age sixteen I became aware of a boy three years my junior who was paying me an unusual amount of attention, which eventually turned into a form of stalking. In time, the boy was joined by a friend of his and they jointly engaged in the obsessive behaviour.

The two friends monitored me while at school and, eventually, at my home as well. They developed a habit of going to my house most evenings and on one occasion plastered my mother’s washing, left on the clothesline overnight, with green stickers. My father was quite annoyed after discovering the cause of the itch he’d been subjected to all day was a green sticker in his underwear. I would sometimes be disturbed at night while lying in bed, becoming aware of the presence of someone below my window. They would never identify themselves, but I knew who they were. On more than one occasion, Dad chased the troublesome duo away from our yard.

Soon after this, I began my first relationship. David was one of the ‘bad boys’ who hung out in the distant regions of the school oval at lunchtimes. He had a reputation for wagging school. I came to realise he must’ve had a bit of experience with girls before he became involved with me, but either way we had our first intimate encounter after school one day when we surreptitiously met in a lane beside the local bank. There I got to experience the mystery and thrill of a first kiss.

David and I shared a fantastic, adventurous stage in our lives for about six months before I suddenly decided to break it off. He’d displayed an earnest devotion towards me and never pressured me to go any further than I was comfortable, which wasn’t far. But after six months, for no rhyme or reason, for me it was just … over.

This sudden, decisive, and even brutal practice of ending relationships for no obvious reason was to become a pattern for me and I would often use feeble excuses to justify my decision. It didn’t seem to matter how loyal or devoted a guy was, I wanted to be free. But as soon as I was free, I would invariably entangle myself in a new relationship, sometimes within a matter of weeks.

One man stands out above the rest, for no other reason than that with him I made one of my biggest mistakes. While I was still a naïve twenty-one-year-old trainee nurse living in the Nurses’ Home in Newcastle, I made the acquaintance of another trainee male nurse, John Bower (pseudonym). Our paths crossed at morning tea time, where he chatted with me over a scone and cup of tea. Eventually, we met up on the top floor of the nursing home, in the ‘library’.

John and I ended up developing what I thought was a close and enduring relationship. He was a nature lover, like me, and I assumed he was a sensitive and caring person. He seemed to be a relatively intelligent person and, perhaps for the first time ever, I actually found myself thinking I might want to marry him one day.

Just before Christmas in 1982, I snuck down to John’s room in the nurses’ home on the 2nd floor and one thing led to another. I even remember the music that was playing, Vangelis’s ‘Chariots of Fire’, as I let out a yelp of pain.

‘You know, you’re not a virgin anymore,’ he said matter-of-factly, but that didn’t matter to me. I thought I was in love.

It was sometime in the ensuing months, when my period didn’t arrive, that I realised I was pregnant. I told John, expecting him to be thoughtful about it, considerate at the very least, but I was mistaken. His immediate response was, ‘Well, you had better do something about thatthen.’

And that was that. No matter my ideals or my still developing inclination towards thinking of abortion as wrong, I couldn’t face the idea of being a mother when I hadn’t even finished my nursing training yet.

In teary disbelief, I boarded the train for Sydney with Carolyn. She sat with me in the waiting room as I waited for my ‘turn’ to commit the murder of my first child. The shame and guilt sat heavily on my shoulders as the minutes passed.

In some ways, I think I feel it even more strongly now. I hadn’t learned much about religion at that stage, but my parent’s moral code made it clear that I had done the wrong thing by engaging in sex before marriage and an even worse thing by having an abortion. I was just glad to have Carolyn there to help me home after.

My mother told me years later, that she had suspected I may be pregnant, but she never discussed her suspicions with my father and never broached the subject with me. Just like John and I had never discussed the matter; I had felt the responsibility solely on my own shoulders.

Perhaps John had been too young and unable to consider the responsibility that came with having unprotected sex outside of marriage or, worse yet, an unplanned pregnancy. He certainly wanted the ‘problem’ to go away. I wonder if John ever knew how difficult it was for me to go through with the abortion, whether he ever even thought about the experience. Would he think of it as murder? Or was it simply having the problem sucked out of the way? Because that’s exactly what happens. The doctor inserts a suction apparatus into the woman’s uterus and you can hear the foetus being suckedout of you. This tiny little bunch of cells, which is so easily discarded, bears no resemblance to the exquisite form of a newborn baby.

John and I had remained in contact, intermittently over the next thirty three years, our relationship tapered down to infrequent catch-ups and occasional get-togethers where we met and shared important events, before fading away completely. Over time, I learnt to forgive myself and I also let go of any issues that I may have had with John. I felt I must not solely blame him. I needed to forgive him but I needed forgiveness too, for my role in the catastrophe. I have now learned that all those people wanting forgiveness by the Almighty were obliged to forgive others. I think I’d need a much bigger knock to the head to forget though. But forget I would, even as I try so hard to remember so much else.

2

Catching Momentum

Shortly following our wedding, Paul and I started a long winding camping trip along the east coast of Australia. With our hang-gliders loaded on top of Paul’s Toyota Land-Cruiser and a newly acquired fold-up camp trailer in tow, we tossed a coin to decide whether to head north or south. South it was. Thinking back on it now, it seems bizarre that we were prepared to choose a direction that would basically influence the rest of our lives on a mere coin toss. That was how carefree we both were.

We were not tempted to stay anywhere more than one night until we reached the town of Corryong, in north-east Victoria, close to the New South Wales border. In fact, the Murray River, which has its source not far upstream from Corryong, forms the actual state border a few kilometres from Corryong. Recent stories in the main national hang gliding magazine, Skysailor, had made us aware of the good hang-gliding sites in the area. We made our camp on the Murray River, next to a lovely timber bridge and under the shade of a stand of huge liquidambar trees.

The campsite on the Murray River

Paul built a camp fire, bordered with large stones that formed a ring. In the middle, he built a fire fuelled by the fallen twigs and limbs from the surrounding liquidambar trees. All around us, the birdlife twittered and chirped in the trees. The beautiful white wings of the cockatoos flew overhead in small gaggles as we prepared our new temporary home. The merry galahs made a raucous announcement that we’d interrupted their peace.

It was a beautiful area for camping, and not far downstream from the outlet of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme, operated and maintained by Snowy Hydro Limited. The Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme is one of the most complex integrated water and hydro-electric power schemes in the world. The Scheme collects and stores the water that would normally flow east to the coast and diverts it through trans-mountain tunnels and power stations. The water stored is then released into the Murray and Murrumbidgee Rivers for irrigation. It took twenty-five years to build, completed in 1974, and more than one hundred thousand people from over thirty countries came to work in the mountains to make true a vision of diverting water to farms to feed a growing nation and to build power stations to generate renewable electricity for homes and industries. Sixteen dams, seven major power stations (two underground), a pumping station, one hundred and forty-five kilometres of inter-connected trans-mountain tunnels and eighty kilometres of aqueducts were constructed. Even before the Scheme was completed, it was named as one of the civil engineering wonders of the modern world.

Today, Snowy Hydro continues to play a vital role in the growth and the development of Australia’s national economy, by diverting water that underwrites over three billion dollars in agricultural produce and by generating clean renewable energy.

Snowy Hydro currently provides around thirty-two percent of all renewable energy that is available to the eastern mainland grid of Australia, as well as providing fast response power to light up the morning and evening rush hours of Sydney, Brisbane, Canberra, Melbourne and Adelaide.

This amazing project in particular, is responsible for the introduction of a huge number and diverse range of highly skilled multi-cultural immigrants to the shores of this ‘lucky’ country and even luckier region of Australia. And many of them stayed.

~ ~ ~

Our routine on this trip was fairly simple. We would brew some early morning coffee on our camp oven, prepare a breakfast, either hot or cold, depending on what we felt like on that particular day, then pack the car before heading out for the day with a packed lunch.

Paul and I got to know the area quite well, relatively quickly, as we flew there. We camped at Towong for about six months, flying our hang-gliders at nearby Mt Elliot and Mt Mittamatite. The town of Corryong, was set in a valley between these two large mountains. From Mt Elliot, a ridge headed northwards toward our campsite. Both mountains had launch sites already established on them, facing the valley. Irrespective of the prevailing wind direction, thermals would invariably travel up the side of the mountain and tempt a budding hang-glider pilot to launch. (Thermals are large columns of warm, rising air that hang-glider pilots use to gain altitude and sometimes distance.) However, the overall conditions had to be taken into account. If the prevailing wind direction was over the back of the mountain, any qualified hang-gliding pilot would know to expect turbulence in the rotored air on launch. The prevailing wind direction was required to provide a breeze up the take-off site, for a successful launch.

Paul and I became quite familiar with the local eagles. I had frequent close encounters with the resident wedge-tails as I flew down the ridge from Mt Elliot towards our camp at Towong. Eagles would occasionally feel comfortable enough to position themselves under my hang-glider’s wing, which was about twelve metres from wingtip to wingtip. Together, we would glide along the ridge, occasionally stopping to turn in a thermal if my variometer signalled the presence of rising air.

Other times, I would unknowingly ‘stumble’ into the eagle’s territory in the air above its nest, which might contain any number of its off-spring.

Eagles were known to be aggressive at times. Occasionally they would gain considerable height above the hang-glider – say 300 metres or so – then, tucking their wings in, dive at the glider,

The eagle would shriek as it dived at my glider, with claws spread, to tear at the fabric of my wing. The bird was just trying to survive and protect its young family.

I generally took the warning seriously and moving my weight slightly to the left or right, would glide away, scanning the trees below and clouds above, for signs of my next thermal lift.

The eagle sometimes damaged my Dacron wing with a beak or claw. The resultant small tear in the Dacron fabric would not affect the hang-glider’s performance much, but it would always make for a good story to tell other pilots.

One day, while driving into Corryong from Towong, I had the good fortune to witness something few people ever get to see. As a passenger in our vehicle in 1987, I had seen two wedge-tailed eagles, high in the air. The birds locked claws in what appeared to be a mid-air embrace, and from a height of about two hundred metres tumbled and fell towards the earth, finally separating just before impact with the paddock below. They both landed on their feet and seemed to shake themselves. I have since been told that I may have witnessed their mating ritual.

A wedge-tailed eagle flying beside Helen’s hang-glider

Our life at this time essentially revolved around flying and we decided to buy a motorised hang-glider from the Newcastle company, Airborne, established by the Duncan brothers. Also called trikes, these machines were relatively new on the scene, but had a good safety record given the fact that an engine failure simply meant you had to glide to the ground in a heavier than normal hang-glider. Having the motor meant you could take off from airstrips or paddocks, and generally gave you much more freedom. Airborne had sponsored me with a hang glider for a short period of time before Myer became involved, so I was familiar with their company.

When my parents were visiting us in Corryong once, I had offered to take my mum for a scenic flight from Corryong airport over the township of Khancoban. Mum agreed, not without some trepidation, but she ultimately had confidence in my flying skills. We flew to a height of about 4,000 feet across the beautiful terrain between the two towns, then landed at Khancoban airstrip – a small, grassy strip of land close to the upper Murray River. It was a beautiful, relaxed morning that we spent together.

Aside from family visitors, Paul and I enjoyed meeting some of the local folk who lived on the nearby ridge of Towong Hill. Max was an older, single farmer who, living with his spinster sister and extremely elderly parents, seemed to have a lot of free time on his hands. Max helped a lot by driving us to either of the two launch hilltops, then retrieving us from wherever we flew to. Max lived at the bottom of Towong Ridge, while halfway up the hill was a married couple, Ron and Sarah Vise, and their two young children. We all became good friends. Paul and I would often land our hang-gliders in a clearing at the top of Towong Ridge, close to both houses. I became not only a frequent guest at these homes, for a cup of tea or a meal, but also a lifelong friend of the occupants.

The Vises ran a business, based on canoeing trips down the Murray river, during which the clients were taught how best to fly fish for the local delicacy of trout. They could then take their trout home to their log-cabin accommodation at the Vise’s property, and enjoy their flavour, cooked either by Sarah Vise or themselves.

On one occasion, when my family were visiting us, we decided to explore the river for ourselves, by canoe.

The canoe carrying my sister Christine (pseudonym) was the first to go over. Christine unfortunately was held under the water and unable to fight her way to the surface. My younger sister Maree’s (pseudonym) husband, nearby, reached down into the water and grabbed her arm, dragging her to the surface.

Very soon, my canoe tipped over as well, depositing all, including the six brightly coloured towels, into the river.

Later, I put my new trike flying skills into action by flying up the Murray River and spotting those six brightly coloured towels, washed up on the river banks. Handy!

Christine, however, has never gone canoeing again, nor expressed an interest in trike flying.

~ ~ ~

On Towong Hill, where our friends Ron and Sara lived, a local developer had subdivided the remaining land along and around Towong Hill, into a variety of sizes and with a variety of appetising features. Both Paul and I were interested in the corner block on Towong Hill, which featured extensive views over the Murray River and surrounding landscape. The height of the hill at that point was approximately two hundred metres above the ground level at the river. It was advertised at the price of twenty thousand dollars, which was to us then, an extravagant amount of money! We went over our financial capacities again and again, in a futile attempt to justify the purchase, but to no avail. Of course we couldn’t buy a vacant block of land. We eventually set this day-dream aside.

Another local we became friends with was Stanley Colt (pseudonym), a hang-glider pilot and owner-manager of the Corryong Country Inn. Paul and I watched the construction of this guesthouse during our stay in the district.

Stanley Colt was a relaxed and generous host. His family lived in the Corryong district and to our knowledge Stanley had been instrumental in opening the area up to the world of hang-gliding. We contacted Stanley, when he was still an active hang glider pilot in the area. Stanley was a highly skilled cook with chef-like qualities. He enjoyed cooking and having recently met and married a woman with mutual interests, was setting up the guesthouse, to operate as a business for the increasingly popular town.

The site of his new business was on the previous site of the op-shop, which Paul and I frequented in order to meet our needs for the increasingly cooler climatic changes.

With our first winter just around the corner in about May 1987, Paul and I applied for jobs at a ski lodge at Charlotte Pass in the New South Wales ski fields. As the weather got cooler, so did our passion for the camper trailer, hence the change. We considered ourselves lucky to get jobs together, in one of the larger guest lodges called the Kosciuszko Chalet Hotel. Paul was employed to manage its three licensed bars (he had gained experience as a manager running his hang-gliding school), while I was employed to work in the bars serving drinks (I had bar work experience from Newcastle prior to beginning my nursing training).

Charlotte Pass, at one thousand six hundred and seventy metres height, is Australia’s highest occupied settlement and therefore its highest ski village. It is also the coldest settlement in Australia. It is very close to the tree line (the altitude above which trees cannot grow), which is about seventeen to eighteen hundred metres in height in the Snowy Mountains, with the beautiful snow gum (Eucalyptus pauciflora) being the highest tree. The village is just a stone’s throw from what is called the main range where Mt Kosciuszko and Australia’s other highest peaks are located.

In summer, you can drive the eight kilometres to Charlotte Pass from Perisher Valley, but in winter the road between Perisher and Charlotte Pass is closed as it is so high it is almost always covered in snow.

One summer, while driving up the Alpine Way, we came across a brumby, not far from Thredbo village. These wild horses were rarely seen by people as they struggled to survive in the extreme climate of Australia’s main range. I felt privileged to have caught site of one of these animals.

The brumby whinnied and pawed the ground, perhaps in tension at having been spotted by me. He shook his head, causing his mane to cascade wildly about his head. The sun caught flecks of dark auburn, deep crimson and honey colours, splaying the colours on a vibrant palate around the horses head. His eyes were wide and bright as he reared up on his large haunches. He galloped off, within a few seconds of my spotting him, but I am eternally appreciative for all horses now. I am constantly dismayed at the poor regard some people have for these animals.

Many sensitive and empathetic individuals regard horses as one of the most beautiful of animals, favored for their grace and their unbridled energy as they rear up on their hind legs, pound the ground with their hooves, snort temperamentally, and charge forward courageously. They truly are a thing of beauty.

My brain-injured mind is now, constantly distracted by images of beauty, whether those images presented themselves to me in faces or in the myriad of the colors present in a rainbow. The artist within me, is and was, always burning to be expressed.

~ ~ ~

People going to Charlotte Pass in winter usually leave their car in the long-term car park at Bullocks Flat and take the ten minute Ski-tube (train) to Perisher; or you can drive to Perisher and catch an over-snow vehicle (a kind of large snowmobile taxi) to Charlotte Pass. The main point here is that when you are at Charlotte Pass in winter there is a strong feeling of being quite isolated: you cannot just jump in your car and leave. So if you are working at a Charlotte Pass ski lodge then you also have to have accommodation there.

Things began well enough at the lodge. The snow season began, as expected, slowly with intermittent light snowfalls, making the air decidedly freezing cold if outside. Kosciusko Chalet is a large approximately fifty-room accommodation ski lodge for singles, couples or families. It caters to all day-trippers to the village as well, providing food and drinks in its licensed bars. The Chalet had a manager already, but Paul was employed to manage the bars, while I was able to secure bar work, under Paul’s direction. We settled into our accommodation for the winter there. It was a small room. Very small. The double bed was hard up against one wall, while the opposite wall could be reached by simply standing at your bedside and extending your arm. Length wise, the room was a smidge more generous. All the winter employees existed in one long corridor. It was cosy. Each room had a window, opening to the north.

In drawing up the rosters, Paul had to account for each of the three bar areas, considering that these bars operated to provide service to the day trippers and customers of the Chalet, as well as to specifically all different ages of the Chalet customers, late night bar services had to be provided as well, for the revellers. That required … you guessed it! Workers prepared to do shift-work! The downstairs bar was the revellers bar, closing at 3 a.m. And all the while, with a happy glamorous female bar attendant in tow! Of course, there were men as well. The female revellers had to be accommodated too!

I worked long hard hours late at night. Just because you were married to the bar manager, didn’t mean you got things any easier. If anything, you more often than not, made up for any short-falls.

What I do remember, is learning to ski downhill on thin cross country skis. Paul and I faced this challenge together, day after day. We were determined to conquer this challenge. Every day, when not working, we would suit up in either our downhill skis and boots or our extra strong telemarking skis and boots and take to the hills of Charlotte Pass.

We had trained ourselves to ski on cross-country skis where your heel is free to move up and down and where you turn using the so-called telemark technique. This is much more difficult than normal downhill skiing, which had not been challenging enough for either of us. In fact, our telemark skis were stiffer and more suitable for the rigors of downhill skiing (using chairlifts) than the relatively light, cross-country skis that people used to cover distances on flatter terrain where there were no chairlifts. Being stronger than me, Paul made more rapid progress in his attainment of the technique. I recall eating many mouthfuls of snow, trying to escape from the tangle of skis and poles, which wrapped around me, as I collapsed in yet another ungainly demonstration of how not to telemark! Anyway, we both became quite proficient at this style of skiing and could be spotted on the beautiful ski runs of Charlotte Pass ski village when we had time off work.

One day, in immense frustration, I threw the sunglasses I had been wearing, a valuable pair of Vuarnet sunglasses, against the wall in the Chalet lounge area. What was worse, the sunglasses belonged to Paul. He had just loaned them to me for the day.

Despite being married for less than a year, Paul soon decided to sack me from my job. He said: ‘I don’t like your attitude.’

It seemed I was a tempestuous female, especially at a certain time of the month. In fact, I often blamed my hormones for landing me in trouble with my husband at that time, and I suppose I’d gotten away with moody behaviour on far too many occasions.

Many years later, I learned that I had developed a pattern of behaviour, which began with working too hard, placing myself under such a heavy work burden that I developed anxiety and stress-induced depression, which resulted in me becoming argumentative with the person who I was closest to: my husband.

But back then I had no insight into either my psychological susceptibility or how to deal with it and so, when Paul was no longer prepared to tolerate my moodiness, he sent me back to Newcastle saying our marriage was over.

When I arrived home at my parents’ house in Newcastle, I cried inconsolably into a pillow. I couldn’t understand what good Paul expected to come from working thathard for nothing but money. My misery could not have been worse had someone died. I sobbed my heart out for days. I bored my friends and family with stories about how wonderful my ‘darling Paul’ was. If I couldn’t be with him, at least I could talk about him. I felt as if my heart was totally smashed.

Paul started a relationship with a young woman, almost immediately following my leaving the chalet. Someone he’d employed to work in the bar not long before, so he must have beenreally heartbroken, too. I got to know all this when I telephoned the lodge one evening and spoke with one of my girlfriends, Christina, who still worked there.

To be fair, Paul had tried to work things out with me by explaining his point of view. It seemed reasonable to him that we should have been prepared to work hard to establish ourselves in a financially secure position so we could capitalise on whatever opportunities came our way. But Paul did not seem to realise that I was working as hard as I could already. He seemed to me to be an unreasonable boss. My increasing moodiness disturbed my attempt to remain a hardworking, dutiful, loving, sexy, attractive girl for him to display on his arm when we went skiing together – one of the few ways we relaxed.

When Paul finally agreed after several weeks that I could return to the lodge, having been suitably chastised for my previous behaviour, the young woman who Paul had had an affair with was gone. Paul, to the best of my knowledge, never saw the young woman again, but he was still prepared to collect a lay-by she had left at a nearby store soon after this to post to her. Paul and I drove to Corryong to collect it: a dress she had taken a fancy to a few weeks earlier. I didn’t complain because I was prepared to do whatever it took to be allowed back into my husband’s life. I loved him to the point of weakness and was simply relieved to be back within my marriage. I willingly accompanied him to the dress shop and watched silently as he completed his task. Yes, I compromised myself, but I believed I could keep my man by being a good little wife.

After we finished working our first winter at the lodge, Paul and I decided to buy our first home. Ron Vise had told us about a house at Khancoban, a town near Corryong, which he thought might interest us. The three-bedroom weatherboard house was on three acres with a decent garden that the previous owner had tended to with considerable devotion. The garden had fruit trees, including stone fruit that were suited to the cool climate. It had well-established ornamental trees, shrubs and some unusual flowers. The scent of those flowers captivated me on our first inspection of the property. A Daphne mesmerised me with its divine scent!

There was also a permanent creek at the rear of the block that fed a water tank that was kept filled by a pump system. Being rural, there was no mains water but we didn’t need it. We loved the property straight off the bat. The owner, a widow, was asking a reasonable price that we thought we could afford if we both worked hard. Paul and I needed to find some fairly secure income to pay the mortgage, as we had only a minimal deposit.

Paul, being a teacher, got a job teaching maths at a high school at Albury, the next-largest town to Corryong, and about an hour’s drive away. I found a job closer to home at Corryong Public Hospital, albeit part-time. My father, Warwick, while visiting us at our new home in Khancoban, happened to bump into the director of nursing of nearby Walwa Bush Nursing Hospital while they were both shopping in Corryong. Somehow, he got to discussing my employment needs and her needs for a permanent full-time night duty nurse at her small bush nursing hospital.

The fact that it took me about forty minutes to drive each way from Khancoban to Walwa was not really an issue – following a night shift, I would leave Walwa at seven thirty am for the forty minute drive home to Khancoban, employing several stay awake methods. For instance, I would often drive along with all the windows down to allow the cold morning air to pummel me. I would then slap my own face repeatedly as frosting on the cake and I managed to make it home safely every time. Once home though, Paul sometimes had to wake me up as I occasionally fell asleep in my car in the driveway.

I recall one night I was sitting in the staff room, while my patients were still sleeping. Dawn was fast approaching, when a dark shape appeared in the ceiling to floor window, which accessed the front verandah of the hospital. In alarm, I shone my torch to its form.

There stood a fully-grown kangaroo! It must have been ailing in some way or another, coming this close to humans. I watched the ‘roo and it hopped away down the main street of early morning Walwa, poking its curious face in here and there.

Eventually, on my way home, I stopped in town, where I saw a lady accompanied by her husband, gently petting the huge kangaroo. Apparently, she had raised the animal from the time of it being a young and abandoned joey.