Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crossway

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

A Hopeful Puritan Perspective on Suffering and Death In the throes of a long illness and confronting the possibility of death, 17th-century theologian Richard Baxter found comfort in the reality of heaven that awaits believers of Christ. During his recovery, Baxter wrote about the afterlife in what would become his best-selling book. The Saints' Everlasting Rest meditates on what Scripture reveals about heaven, helping believers live an abundant, God-honoring life in anticipation of eternal rest. Baxter encourages readers not to become distracted or discouraged by the temporal as he refocuses their minds on the eternal. Confronting difficult topics including sin, suffering, and fear of death, he also emphasizes God's sufficient grace and how the promise of heaven enriches life on earth. - Foreword by Joni Eareckson Tada: Inspiring message from the founder and CEO of the Joni and Friends International Disability Center - Great for Personal and Group Study: Each chapter ends with questions for reflection, tackling issues including death, abundant joy, security in Christ, and patience through affliction - Modernized Version of a Puritan Classic: Abridged and edited, with a detailed summary of Baxter's life and work, along with short introductions to each chapter - Biblical Support for Dealing with Grief or Illness: Explains suffering and death from a Christ-centered perspective, with practical tips for living a heavenly life

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Thank you for downloading this Crossway book.

Sign up for the Crossway Newsletter for updates on special offers, new resources, and exciting global ministry initiatives:

Crossway Newsletter

Or, if you prefer, we would love to connect with you online:

“The Saints’ Everlasting Rest is a classic treatise on a favorite Puritan topic: the glory of being with Christ forever. Richard Baxter not only teaches us about heaven in a manner that fans hope into flame, but he also teaches us how to meditate on heaven so that we can enjoy a foretaste of it already on earth. Tim Cooper has done us a great service in distilling Baxter’s one thousand–plus pages of seventeenth-century Puritan prolixity into a small and accessible book. May this burning coal ignite a fire in many hearts today!”

Joel R. Beeke, President and Professor of Systematic Theology and Homiletics, Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary; author, Reformed Preaching; coauthor, Reformed Systematic Theology

“‘Could you not watch with me one hour?’ Christ’s gentle correction applies to us as well when our spirit is willing but our flesh is too weak to meditate on heaven for one hour. But in this volume are corrective words from Richard Baxter that—though updated and abridged—retain their well-earned and long-standing approval. Taking us by the hand, Baxter draws us away from our egregious neglect of duty and leads us into the joy of thoughts that ring with faith, desires that ache for paradise, and disciplines that dispose us again toward the rest that Christ is preparing for us in our Father’s house.”

A. Craig Troxel, Professor of Practical Theology, Westminster Seminary California; author, With All Your Heart

The Saints’ Everlasting Rest

The Saints’ Everlasting Rest

Richard Baxter

Updated and Abridged by Tim Cooper

Foreword by Joni Eareckson Tada

The Saints’ Everlasting Rest: Updated and Abridged

Copyright © 2022 by Tim Cooper

Published by Crossway1300 Crescent StreetWheaton, Illinois 60187

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law. Crossway® is a registered trademark in the United States of America.

This book was originally published by Richard Baxter in London, 1650. In this edition, that earlier work has been abridged and the English modernized. See the introduction for more about what the editor has updated in this edition.

The images in this book come from Dr. Williams’s Library in London. Used by permission.

Cover design: Jordan Signer

First printing 2022

Printed in the United States of America

Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations are from the King James Version of the Bible, though the English has been modernized by the editor, with some consulting of modern translations. Public domain.

Scripture quotations marked ESV are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. The ESV text may not be quoted in any publication made available to the public by a Creative Commons license. The ESV may not be translated into any other language.

All emphases in Scripture quotations have been added by the author.

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-4335-7887-8 ePub ISBN: 978-1-4335-7890-8 PDF ISBN: 978-1-4335-7888-5 Mobipocket ISBN: 978-1-4335-7889-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Baxter, Richard, 1615–1691, author. | Cooper, Tim, 1970–

Title: The saints’ everlasting rest / Richard Baxter ; updated and abridged by Tim Cooper ; foreword by Joni Eareckson Tada.

Description: Updated and abridged edition. | Wheaton, Illinois : Crossway, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021026067 (print) | LCCN 2021026068 (ebook) | ISBN 9781433578878 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781433578885 (pdf) | ISBN 9781433578892 (mobi) | ISBN 9781433578908 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Devotional literature.

Classification: LCC BV4832.3.B492 C66 2022 (print) | LCC BV4832.3.B492 (ebook) | DDC 242—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021026067

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021026068

Crossway is a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.

2022-03-18 10:15:35 AM

Contents

Foreword

Joni Eareckson Tada

Introduction

1 What This Rest Contains

2 The Four Corners of This Portico

3 The Excellent Properties of This Rest

4 What We Will Rest From

5 A Multitude of Reasons to Move You

6 Why Are We So Reluctant to Die?

7 The Heavenly Christian Is the Lively Christian

8 Dangerous Hindrances and Positive Helps

9 I Now Proceed to Direct You in the Work

10 How to Fire Your Heart by the Help of Your Head

11 The Most Difficult Part of the Work

12 Preaching to Oneself

Conclusion

Appendix: Book Outline

General Index

Scripture Index

Foreword

The first time I read the work of a Puritan preacher, I barely made it through the second chapter. I was told there were hidden treasures for my soul in those pages, but I lacked the mental toughness needed to break through the impenetrable text. I pushed it aside. Shakespeare is easier than this, I decided. At the dewy age of seventeen, so many other, more inviting and alluring paths beckoned.

Then I broke my neck, and all bets were off.

No longer could I wade in the comfortable shallows where my faith was ankle-deep. Head over heels, I had been heaved out into the depths of God, where I could not touch bottom, and I was sinking fast. Oh God, help!

And who, besides the Almighty himself, could begin to fathom the frightening depths in which I found myself? Yes, the psalmist tells us that “deep calls to deep” (Ps. 42:7 ESV), but where could I find those who had plumbed this Mariana Trench I was in? Could someone—anyone—show me how not to fear it but to find God in it?

Return to the Puritans, I thought. And I’m so very glad I did. From Jeremiah Burroughs, I learned to subtract my desires to fit a life of paralysis. Samuel Rutherford told me not even to think about sneaking quietly into heaven without a cross. Jonathan Edwards helped me explore that awe-filled trench, that vast, bottomless ocean of God. And Thomas Brooks said that next to Christ, I should set the choicest saints before me as a pattern for living. I did just that with the likes of these valiant, far-seeing men.

When hard suffering is your daily fare, you gravitate toward people who are deeply serious about God, life, and faith. Your spirit resonates with them. You recognize—and trust—their counsel, and you easily fall into the irresistible orb of their love for Jesus Christ. The Puritans have that inexorable pull. And it’s the Puritans who beckon us beyond the shallows and into the glorious depths of God, where the inability to touch bottom never ignites fear but rather generates sheer delight.

Doesn’t every Christian want this? Doesn’t every believer want to go deep, even if it’s costly? Don’t we all long for and look forward to heaven? I sure do. It’s not just the prospect of “setting aside this tent,” as the apostle Peter put it (cf. 2 Pet. 1:14). And it’s not really because I yearn to wrestle free of this confounded thing called affliction. It’s more than those things. The Puritan exposition of the Bible shows how my joyous daily carrying of a cross holds a mysterious connection to a far greater joy (inexplicable and unspeakable), worship, and service of God in heaven.

Nowhere is this idea expounded more thoroughly than in Richard Baxter’s timeless classic The Saints’ Everlasting Rest. For centuries it has been lauded as the quintessential work on our heavenly rest and how we can best prepare for it. Baxter embarked on this subject while recovering from a serious illness. As he looked death full in the face, his thoughts naturally turned toward heaven. He asked himself, “What is it like? How can I prepare for it?” His study resulted in an immensely weighty book that was a spectacular bestseller in the 1600s.

Yet nowadays when you try to read the original version of The Saints’ Everlasting Rest—even earlier abridgments—it’s like paddling a canoe upstream on a swift-running river. The concepts and phrases rush at you. It’s a complex, convoluted text that only a persnickety, pedantic grammar czar could love.

This is where our hero Tim Cooper boldly wades into the stream. Tim is not only professor of church history at the University of Otago in New Zealand but a renowned expert on Richard Baxter. With consummate care and expertise, Tim tackles The Saints’ Everlasting Rest with all the respect and honor due this lauded Puritan. (And so he should, given that Baxter’s contemporaries claimed their friend was in a class with the early church fathers.) Tim has performed heroic surgery on this seventeenth-century masterpiece—relieving it of the interminable sentences, semicolons, and subordinate clauses so bewildering to a modern reader.

When I read this new abridged version of Baxter’s treatise, I was enthralled. Captivated. I was so invigorated, I immediately stopped and thanked God for the likes of Tim Cooper. Here is a man who possessed the mental toughness needed to break through the impenetrable language, revealing sparkling treasures such as these:

Take your heart once again and lead it by the hand. Bring it to the top of the highest mountain. Show it the kingdom of Christ and the glory of it. Say to your heart, “All this will your Lord bestow on you. . . . This is your own inheritance! This crown is yours. These pleasures are yours. This company is yours. This beauteous place is yours. All things are yours, because you are Christ’s and Christ is yours.” (chap. 10)

Hold out a little longer, oh my soul, and bear with the infirmities of your earthly tabernacle, for soon you will rest from all your afflictions. (chap. 4)

Be up and doing; run, strive, fight, and hold on, for you have a certain glorious prize before you. (chap. 4)

Heart-stirring exhortations such as these do not play well in a Christian culture that equates heaven more with end-time prophecy than a joyous rest for happy saints. Richard Baxter does not fit in a church that is quick to pray away suffering rather than embrace it as providence. Believers who are content to know little of God cannot know much of what it means to enjoy him, and so their interest in Richard Baxter is summed up in a two-line quotation shared on Instagram or Facebook.

But not me—and not many thousands like me. So if you are ready to set your heart on things above and train your affections on God, if you want to strive harder for your glorious prize and drive your heart ever onward and upward, if you feel that this is the season you finally leave the comfortable shallows of God and dive into his mysterious, wondrous depths, you could have no better guide than the remarkable work you hold in your hands.

Let the Spirit-driven exhortations in The Saints’ Everlasting Rest explain to your heart its final home. For as our Puritan friend says,

Oh my soul, . . . there is love in [Christ’s] eyes. Listen, does he not call you? He bids you stand here at his right hand. . . .

Farewell, my hard and rocky heart. Farewell, my proud and unbelieving heart. Farewell, my idolatrous and worldly heart. Farewell, my sensual and carnal heart. And now welcome, most holy and heavenly nature. . . .

Ah, my drowsy, earthy, blockish heart! How coldly you think of this reviving day! Do you sleep when you think of eternal rest? Are you leaning earthward when heaven is before you? Would you rather sit down in the dirt and dung than walk in the court of the palace of God? Come away! Make no excuse, make no delay. God commands you, and I command you: Come away! (chap. 12)

Oh friend, my heart leaps for joy at such an exhortation! Heaven is about to burst on the horizon, so wake up your soul, and put oil in your lamp. Join me in preparing yourself for that glorious day when we will put on sparkling raiment and ascend the throne with our bridegroom to be presented before God Almighty himself. Do not tarry one minute longer—turn the page, and begin turning your heart toward heaven, your real home.

Joni Eareckson Tada

Joni and Friends International Disability Center

Agoura Hills, California

Introduction

Richard Baxter (1615–1691) was one of the most significant seventeenth-century English Puritans and certainly the most prolific. He wrote around 140 books in the course of his long life. They traverse almost every conceivable subject, from history to philosophy to theology, and they range across all aspects of Christian thought and practice. All share the Puritan concern for earnest endeavor, and all are enriched by Baxter’s experience as a pastor in the parish of Kidderminster during his ministry there from 1647 to 1660. He was an author whose published works drew both notoriety and devotion. His more controversial books have been left to languish in the seventeenth century, but his “practical works” were republished in the eighteenth century and remain available online today. Among those works, two stand out above all others: The Reformed Pastor and The Saints’ Everlasting Rest. They now form a matching pair of Crossway abridgments. Both abridgments seek to distill the genius of each book while rendering Baxter’s language in contemporary English. The aim is to allow modern readers to encounter these two classic works in a fresh and accessible way.

The Saints’ Everlasting Rest has been republished again and again since it first appeared in 1650.1 In Baxter’s day it had reached eight editions by 1659 and twelve editions by 1688; we would call it a runaway bestseller. Many readers sent letters of approval to the author. From all the way across the Atlantic in 1656, for example, the early American missionary John Eliot thanked Baxter for the book: “Oh, what a sweet refreshing the Lord made it to be unto me, especially when I came to that blessed point and pattern of holy meditation.” Baxter, he observed, had “a rare gift, especially to follow a meditation to the very end, bring it to an issue, and set it forth for a pattern.”2Nearer to home, the Wiltshire minister Peter Ince wrote to say, “I do not know of any book that the Lord has made more use of for rousing up men to an active faith than yours.”3

In focusing on heaven, The Saints’ Everlasting Rest clearly touched a nerve and met a need. The book’s broad success may have had something to do with the tumultuous quality of England’s history during Baxter’s lifetime: civil war, the execution of the king, the formation of a republic, the restoration of the monarchy, the persecution of Puritan Nonconformity, and the “Glorious Revolution.” In times of such upheaval, who would not welcome a message of our eternal rest? And ever since then, the book has been in print almost continuously as a stand-alone work. There is something about its heart, its insight, that justifies its continued availability. It can speak to our own day just as well as to Baxter’s. But to grasp the book’s compelling quality, we need to understand the context in which he first began to write.

Baxter’s War

England was torn apart by civil war during the 1640s. The conflict emerged from tensions over political liberties, constitutional prerogatives, financial pressures, and, above all, religious differences. King Charles I imposed on the Church of England a distinctive vision of deference and order along with a new demand for uniformity of practice. The result was a heavily sacramental and liturgical style of worship that minimized the place of preaching and Scripture in the corporate life of the church. Charles and his archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, actively sidelined Calvinist doctrine with its focus on God’s effectual saving grace in predestination and election to promote in its place a doctrine of salvation that valued human free will and moral responsibility. It all looked worryingly Roman Catholic at a time when the Protestant Reformation seemed to be in retreat on the continent of Europe.

When the Irish Catholics rebelled in 1641, with rumors that the king himself had sanctioned their revolt, Parliament took control of the various militias organized to put down the uprising. In October 1642 actual fighting broke out between Parliament’s forces and those of the king, the beginning of four years of bitter military conflict that ranged across the entire country and, in later phases, even into Scotland and Ireland. The destruction was immense and widespread, the loss of life brutal. It is estimated that in the course of those wars, 868,000 people died in battle or were brought down by disease across all three countries, more than 10 percent of the total population.4

The 1640s, then, presented England with a grievous trauma on a national scale. That trauma was mirrored in the experience of countless individuals, not least Richard Baxter. In an uncanny combination of circumstances, he was present to witness the first physical skirmish of the war, an impromptu ambush of parliamentary soldiers.5 He was also on hand to see for himself the mournful aftereffects of the first full battle of the war, fought at Edgehill precisely one month later. He visited the battlefield the following day, where he saw “about a thousand dead bodies in the field between the two forces, and I suppose many more buried before.”6 He offered no comment on the grisly sight, but it must have been a harrowing scene. Baxter was intimately familiar with the grim reality of the war from the very beginning.

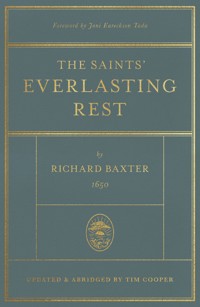

At this stage in his life, he was embarking on a period of itinerancy, having been thrust out of his fledgling pastoral ministry at Kidderminster “by the insurrection of a rabble that with clubs sought to kill me.”7 The Midlands lay in Royalist territory, which was hardly welcome terrain for a Puritan such as Baxter, so he spent the next few years living in Coventry ministering to the garrison stationed in the city. In July 1645 he signed up as an army chaplain in an effort to combat the spread of bad doctrine in the army. He joined the regiment of Colonel Edward Whalley as it traversed the country fighting the last battles against the king and laying siege to several sites of lingering resistance. At the start of 1647, just as the winter reached its coldest point, his nose started to bleed. In the medical wisdom of the day, this was taken to represent an excess of blood, so he opened four veins, followed by another more substantial purge. This drastic loss of blood very nearly killed him.8 As he explained in a letter to a friend that he wrote at the time, “I was never yet nearly so low, . . . and if I see your face no more in the flesh, farewell till eternity.” His only hope lay in prayer: “There is no other hope left: physicians, nature, flesh, blood, spirit, heart, friends all fail. But God is the strength of my heart and my portion forever.”9 He was quoting Psalm 73:26, which appeared on the title page to The Saints’ Everlasting Rest (see fig. 1).

Indeed, the crisis may have ended Baxter’s work as an army chaplain, but it triggered his writing career. As he started a slow recovery, now aged thirty-one, he began to write what he initially intended as his funeral sermon, presumably a gathering of his final thoughts to preach to himself. Those thoughts steadily grew into The Saints’ Everlasting Rest: what you have in your hands is therefore a compressed version of Baxter’s dying words, even if he lived for another forty-five years. As he explained when he dedicated the book to his beloved parishioners at Kidderminster, it was “written, as it were, by a man who was between living and dead.” In that condition, “far from home, cast into extreme languishing by the sudden loss of about a gallon of blood, I bent my thoughts on my everlasting rest.”10 His book urges us to do the same, to turn our minds toward heaven and the prospect of our rest in the presence of God after a weary pilgrimage through this dismal world.

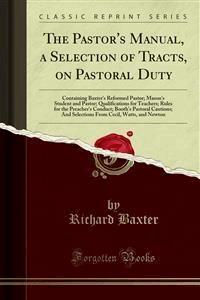

Figure 1 Original title page of The Saints’ Everlasting Rest. Used by permission of Dr. Williams’s Library, London.

And Baxter’s world had been dismal. As he explained to Colonel Whalley in a letter of 1654, “The memory of those [war] years is so little delightful to me that I look back on them as the saddest of my life.”11The Saints’ Everlasting Rest may focus the mind on heaven, but there is no avoiding the bleak reality of Baxter’s earthly experience at a time of turmoil, devastation, and crisis on both a personal and a national scale. Thus the Civil Wars intrude into his book again and again. In one extended lament, he observes the “days of common suffering when nothing appears to our sight but ruin: families ruined, congregations ruined, sumptuous structures ruined, cities ruined, country ruined, court ruined, and kingdoms ruined.” He recalls “the sad and heart-piercing spectacles that my eyes have seen in four years of civil war: in this fight a dear friend falls down by me; from another battle a precious Christian is brought home wounded or dead; scarcely a month, hardly a week without the sight or noise of war” We might take a moment to reflect on what it would have been like for him to live through two years of horror on a regular basis. He surely had in mind the grisly tableau at Edgehill when he looked forward to that time when, as he said, “my eyes will never more behold the earth covered with the carcasses of the slain.” Thus Baxter emerged from the wars with a lingering sense of trauma that infiltrates The Saints’ Everlasting Rest, even as his book points toward an eternal future of commanding joy and rest.

Baxter’s Method

Despite the severity of his near-death encounter in the winter of 1647, Baxter was grateful for it. That experience, he recalled, “forced me to that work of meditation that I had formerly found so profitable to my soul.”12 It would seem, then, that meditation had been a regular practice for him, now perhaps more intensely focused on the prospect of his imminent heavenly rest. As he developed his book, he intended to bring the reader into a new resolve to practice this “work of meditation.” The method he pioneered for himself he now enjoined on his audience, and he does not call it a “work” for nothing. For Baxter, meditation was not merely the passing of some fleeting thoughts through the mind as the occasion arises. It involved focus and effort; it was determined, intentional, structured, deliberate, and regular; it embodied what he called the “great duty of a heavenly life.” There were many hindrances in its way, particularly in the sluggish workings and perverse reluctance of the human heart. In his experience, it was a rare Christian who practiced daily meditation on heaven. But the effort brought great gain for those who would make it their own. He had proved that for himself.

Baxter’s method was grounded in a tripartite understanding of the nature of each human person: judgment, will, and affections. Christian truths were inadequate if they resided only in the mind, or the judgment. The will had to be brought into play to move those divine truths from the judgment into the affections, from the head to the heart. The main way of doing this was through soliloquy, or “preaching to oneself.” Centuries before the development of modern psychological theories, Baxter intuited the power in the way we talk to ourselves. His other word for this self-talk is “consideration,” which “opens the door between the head and the heart.” Consideration is a reasoning with oneself. His method of meditation involves us in coaxing our own hearts with sufficient reasons to move our affections. With time, effort, and resolve, our emotions begin to answer, we feel the force of those truths, and our hearts are lifted up in love, desire, hope, courage, and joy (chap. 10). The crucial element in achieving these gains is how we talk to ourselves. One of the most compelling and endearing aspects of the book is that Baxter increasingly allows us into his own mind to hear for ourselves how this great Puritan spoke to himself. The final chapter provides an exemplar of his own meditation. The Saints’ Everlasting Rest is a personal gift of the most intimate kind.

Baxter’s method was also grounded in the conviction that God does not work mysteriously, as if by magic; he works by means, and those means are at our disposal. “Man is a rational creature and apt to be moved in a reasoning way.” Each of us is capable of using our own God-given faculties to bring divine truths home to our heart: “Must not everything first enter your judgment and consideration before it can delight your heart and affection? God does his work on us as men and in a rational way. He enables and energizes us to consider and study these delightful objects and thus to gather our own comforts as the bee gathers honey from the flowers.” Just as bees work hard and work methodically to gather their honey, so too, Christians are to work in the way God has designed them to work. He “enables and energizes us,” but there is no honey without our own cooperation. “You will enjoy God only as much as you train your understanding and affections sincerely on him.”

Much of the book carries Baxter’s reflections on what the saints’ experience of heaven will be like. With a richness of texture and imagination, Baxter weaves together scriptural signposts with his thoughtful impressions of what the future might hold when we will be fully alive at last in the presence of God. He also impresses on us how our present life must necessarily change if we genuinely take that prospect to be true. This is his manifesto for how we are to live and how we are to die—on a daily basis. Baxter’s challenging insights become a succession of wedges that pry our attachments away from the pleasures and comforts, the customs and values of this world. His deep impressions could only have come from extended reflection on heaven. They are the product of his method, and he invites us into the same practice of daily meditation that generated those insights. There is an urgent authenticity to his book. In those dismal days of civil war, he set his sights firmly on heaven. In these more comfortable times, four centuries later, he challenges us to do the same. Do you really believe in heaven? Reading this book will put that belief to the test.

But if we are prepared to put in the work of daily meditation, we will reap a rich reward. As Baxter explains in the book’s conclusion, “Be acquainted with this work, and you will, in some small, remote way, be acquainted with God. Your joys will be spiritual, prevalent, and lasting, according to the nature of their blessed object”.Those joys will bring great gain even in the worst of circumstances.

You will have comfort in life and comfort in death. When you have neither wealth, nor health, nor the pleasure of this world, yet you will have comfort: a comfort without the presence or help of any friend, without a minister, without a book; when all means are denied you or taken from you, even then you may have vigorous, real comfort.

To pilgrims on a journey through a dark and painful world, such comfort will be welcome indeed.

Baxter’s World

But is the world as dark as all that? Very few, if any, contemporary readers of this book will find themselves in the middle of a vicious civil war. We live in a historical moment of relative comfort, safety, and affluence; is Baxter’s experience going to speak to our own? Throughout the book he talks a lot about happiness, but it is not reassuring when he claims that “happiness is hereafter, and not here.”13 In other words, happiness is something we should look for only in heaven; we should not expect to find it or even seek it here on earth. This is not our home; here we only get by. “This world,” he says, “is a howling wilderness,” and “most of the inhabitants are untamed, hideous monsters.” We are soldiers in the midst of battle, sailors still seeking safe harbor, and travelers making our weary way home. Only then will we rest. In the meantime, our earthly life is filled with labor and travail, and we should expect no less. This is, to say the least, a bleak perspective.

It is worth noting that Baxter had other reasons to be weary of this world that had nothing to do with civil war, and perhaps these other dimensions will resonate more with our own experience. To begin with, he battled ill health his whole life long. He was, in the apt words of Neil Keeble, “subject to a bewildering variety of physical ailments.”14 To name a few: kidney stones; pain in his eyes, teeth, jaws, and joints; and what he described as “incredible inflammations of my stomach, bowels, back, sides, head, and thighs.”15