Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

From the cocreator of Deadpool and author of Suburban Dicks comes a diabolically funny murder mystery about the dark underbelly of suburban marriage After mother of five and former FBI profiler Andie Stern solved a murder—and unraveled a decades old conspiracy—in her New Jersey town, both her husband and the West Windsor police hoped that she would set aside crime-fighting and go back to carpools, changing diapers, and lunches with her group of mom-friends, who she secretly calls The Cellulitists. Even so, Andie can't help but get involved when the husband of Queen Bee Molly Goode is found dead. Though all signs point to natural causes, Andie begins to dig into the case and soon risks more than just the clique's wrath, because what she discovers might hit shockingly close to home. Meanwhile, journalist Kenny Lee is enjoying a rehabilitated image after his success as Andie's sidekick. But when an anonymous phone call tips him off that Molly Goode killed her husband, he's soon drawn back into the thicket of suburban scandals, uncovering secrets, affairs, and a huge sum of money. Hellbent on justice and hoping not to kill each other in the process, Andie and Kenny dust off their suburban sleuthing caps once again.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 513

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Fabian Nicieza

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: Only the Goode Dies Young

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Part Two: An Affair to Dismember

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

Part Three: In Slickness and in Wealth

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

Also by Fabian Nicieza

SUBURBAN DICKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

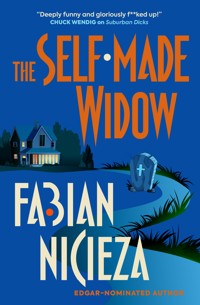

The Self-Made Widow

Print edition ISBN: 9781803360096

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803360102

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First Titan edition February 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © 2023 Fabian Nicieza. All rights reserved.

www.titanbooks.com

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Tracey, my Sisyphus of patience,along with Mariano and Marie, Steve and Stacie, Steveand Nina, John and Karen, Rick and Francesca,Bill and Mary, Laura and Mike, Thea and Reynold,Lorie and Jeff, Kim and R.J., one and all shiningexamples of suburban marriages done right!

PART ONE

ONLY THE GOODEDIES YOUNG

DEREK GOODE rarely had pleasant dreams anymore. Between stress at work, stress at home, and stress about stress, he had been very stressed. His partnership track at the firm had been derailed. Even though his side project had generated much more revenue than he’d expected, now he was worried it would all blow up on him. Molly had been mad at him all summer, but he’d been too afraid to ask why. Henry hadn’t made the premier soccer team, and Brett had started to display blatantly effeminate inclinations. For Derek, surprisingly, that had become a source of tremendous pride, though for Molly, unsurprisingly, a source of tremendous anxiety.

All things considered, when Derek went to sleep that night, it was understandable that his subconscious would be working overtime. His dream started off in quite a pleasant manner. It was a perfectly crisp summer day. No kids in the house. He wondered if it was even his house, since there were empty glasses left on the kitchen island and one couch pillow seemed slightly askew, which Molly would never allow.

He opened the stainless-steel refrigerator to find it completely filled with Kentucky Bourbon Barrel Ale. He grabbed one, then a second, and strolled into the backyard. Curiously, Molly was digging a hole in the walking garden. More curiously, she was wearing a black string bikini. She hadn’t worn a bikini since she’d gotten pregnant with their oldest, Henry.

Thirty-eight and after two kids, in a dream or out, she looked great. Runner’s body, flat abs, and her breasts were pre-kids. It was his dream, so he rolled with it. Her body glistened with sweat and her lean, tight legs were smeared with topsoil. She looked incredibly sexy. That was the thing about Molly: cold as ice, but hot as hell.

Derek shielded his eyes from the strong sun. The light was ridiculously bright.

He asked, “What are you doing?”

“Digging a hole,” she said.

“What for?”

She didn’t respond, but when she thrust the spade into the ground again, Derek clutched at his chest.

Molly dug into the ground again and he collapsed to his knees. He tried to get her to stop, but the words came out garbled.

She looked at him.

She smiled.

She went in for a third shovelful. He gasped for breath, but none came.

Did people breathe in dreams? Derek wondered.

Molly dug the shovel one more time, with greater force. She slowly twisted the shaft so that the blade ground into the dirt with a sickening scrape. To Derek, it felt like her every move was twisting his chest into knots.

He thought about the boys and how unfair this would be to them.

He wished he could see them again, but the sun was too blinding.

“Wow,” he muttered. “That light is really bright.”

And then Derek Goode died.

* * *

IT WAS 7:20 a.m. when West Windsor Police Department patrol officers Michelle Wu and Niket Patel pulled into the Windsor Ridge complex to address the 911 call. The paramedics had arrived moments before them. Emily and Ethan Phillips were entering the house. The twins had been born and raised in town and had joined the coincidentally named Twin W First Aid Squad while they were in college.

There was a third car in the driveway that led to a three-bay garage. Michelle assumed the husband and wife kept their cars inside, and their children weren’t old enough to drive. Had Molly Goode called someone before she called the paramedics? More people in the house meant more emotion to deal with, and Officer Wu despised human emotion.

“I hope I don’t have to string up a perimeter,” muttered Niket, a joke between them alluding to the murder of a gas station attendant last year in which he had spectacularly lost a wrestling match with a roll of crime-scene tape.

“Pretty sure it’ll be natural causes,” Michelle replied, to Niket’s great relief.

They were greeted at the front door by a woman with a Cheshire smile. It looked sincere but also entirely inappropriate for the moment. She had shellacked blond hair, with large, inviting eyes. Michelle was unnerved, less because of the woman’s warmth and more because the officer recognized her. But from where?

“I’m Crystal Burns,” she said. “I’m Molly’s best friend. She’s upstairs with the paramedics.”

Officer Wu noted that Molly Goode’s two sons were sitting in the kitchen. The younger boy cried as his older brother consoled him. The house was immaculate. Practically sterile. As she mounted the half-turn stairs, Michelle caught a ray of sunshine coming through the foyer window and couldn’t see a single particle of dust floating in the air.

They stepped past Molly, who stood by the entrance to the master bedroom, tissue in hand but not a tear in her eye. Michelle noted a flash of tentative recognition in Niket’s eyes. Molly looked as familiar to the two patrol officers as Crystal had.

The paramedics were inspecting Derek Goode’s body. He lay in his bed, his hands frozen where he had clutched at his chest. His eyes remained wide open, staring to the ceiling. Heart attack was Michelle’s first thought. He wore a faded Creed T-shirt from their 1999 Human Clay tour, which Michelle assumed he would never have worn had he known he’d be dying in it. Plaid boxer shorts and white ankle socks completed the regrettable shroud ensemble.

He had been a handsome man, tall with brushed-back brown hair that was graying at the temples. He was in good shape. Both of the Goodes were.

Michelle eyed Molly, who wore an Alala Essential long-sleeve workout shirt and Vuori Performance jogging pants. That was almost two hundred bucks’ worth of workout clothes just to greet the paramedics. That was on the high end of unnecessary, even by the standards of West Windsor, New Jersey.

Molly Goode was pristine. Loose auburn hair, uncolored, bounced in a bob at her shoulder. She still had freckles, which gave her features a youthful glow that contrasted with her stern demeanor. She was five feet seven, thin and taut. It was clear Molly exercised quite a lot. Michelle thought, No hidden bag of Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups in this one’s night table drawer.

“I’m sorry for your loss,” Michelle said.

Ethan Phillips said, “Patient is nonviable. We have to call the medical examiner.”

“I didn’t hear anything,” Molly said. “I woke up at six forty-five to get the kids ready for school and I thought he was still sleeping. I heard his alarm go off from the kitchen at seven. When it didn’t stop, I came up to see why and—and he was . . . hewas . . .” She hesitated.

When Emily Phillips caught Michelle’s glance, the paramedic said, “Rigidity has set in. I’d estimate time of death was about”—she looked to her brother—“four hours ago?”

“Give or take thirty minutes,” her brother confirmed.

“Give or take,” Emily agreed.

The doorbell rang. Crystal’s loud voice echoed from the foyer as she let someone in. Michelle peeked out from the bedroom over the foyer railing. Another woman had arrived. Short, thin, with tightly cropped wavy brown hair and a raspy voice. Michelle recognized her, too.

And then she remembered where she knew these women from.

Shit, she thought.

“Molly, Bri is here,” Crystal called out, her voice echoing.

“Excuse me,” said Molly as she went downstairs to greet Brianne Singer.

Niket had also come to the same realization as Michelle, saying, “Those three women . . .?”

“Yes,” Michelle replied with dread in her voice.

The doorbell rang again.

With unintentionally synchronized timing, Michelle and Niket turned to look at each other.

Incapable of ignoring the bug-eyed fear on the cops’ faces, Ethan asked, “What’s wrong?”

The front door opened to the piercing wails of a crying baby. Lungs capable of rattling the three-thousand-dollar foyer chandelier blasted their noise through the house.

“Veshya kee santaan,” Patel cursed in Hindi.

They could see her downstairs.

Her.

Andrea Stern.

She held her eleven-month-old baby and a diaper bag with her right arm. Completely indifferent to the child’s howling, she hugged Molly with her free arm. Her curly dark hair was shorter and less enraged than the last time Michelle and Niket had seen her. From a circumference standpoint, Andrea had deflated about 85 percent from the size she had been during her pregnancy. Michelle quickly did the math and couldn’t reconcile how the woman had given birth to a fifty-pound baby.

Andrea whispered something into Molly’s ear. Molly nodded.

Michelle Wu took a step back as Andrea, still carrying the fleshy foghorn, made her way up the stairs. She entered the bedroom, nodding politely—no,sarcastically—at Wu and Patel.

“Officers,” Andrea said in a sweet, lilting voice that fought against its native Queens accent.

Remaining indifferent to the child’s incessant wailing, Andrea stopped just inside the door frame and scanned the room. She absorbed every detail. The position of the covers. Derek’s frozen posture. The alarm clock on his side of the bed. The master bathroom door was open, so she could see the double-sink counter, where everything was arranged in a strict, regimented manner.

The baby kept crying. Michelle noted it was another girl. That made four girls and one very outnumbered boy.

The paramedic siblings looked uncertain as to what was going on. By now, nearly everyone in the sister towns of West Windsor–Plainsboro knew who Andrea Stern was. Besides having solved the murder of Satku Sasmal and having severely damaged the reputations of the West Windsor Police Department and township administration, she also had become a monthlong global viral sensation. A video of her water breaking in the middle of the heavily attended news conference last fall had made the rounds, exploding on Twitter before going through several TikTok variations. It had been entertaining though hollow revenge for those who had blamed Andrea for shattering the illusion of their storybook suburban lives.

Andrea was an investigative savant who should have been an FBI profiler but had ended up becoming a baby-making machine. While still in high school, she had solved the case of Emily Browning, missing in South Brunswick for twenty years. In college, Andrea had cracked New York City’s notorious Morana serial killer case. She had also gotten pregnant before graduating, which had derailed her goal of working for the FBI.

Over the past year, she had become a semi-regular fixture at police headquarters as Detectives Rossi and Garmin had taken to requesting her advice on several cases. Even the mayor, who happened to be Officer Michelle Wu’s mother, had asked for Andrea’s input on administrative matters a few times.

Now, just as she had the first time the officers had met her, Andrea Stern was performing what the media had come to call “panoramic immersion.” The small, annoying woman visualized the moment of Derek’s death, capturing a mental image of the events as they had unfolded while retaining a photographic memory of the most minute details in the room.

The first time Michelle had seen Andrea do this—at the gas station where Satku had been killed—had unnerved her. This time, the officer was thankful as Andrea snapped out of it quickly and looked at her baby with a bemused, gentle smile.

“Hey, JoJo,” she cooed. “You smell like fifty pounds of shit in a five-pound bag.”

She spun the crying baby onto the bed right next to Derek’s body. She slung the diaper bag so that it practically landed on the supine corpse. She removed the baby’s diaper, which smelled like a Taco Bell had relieved its bowels in the middle of another Taco Bell. She removed wipes and a fresh diaper. Then, as if by prestidigitation, she cleaned and changed the baby with such speed that Michelle needed a slow-motion replay to confirm it had actually happened.

“That was a super-stinky poop,” Andrea baby-talked.

The baby stopped crying.

Stern slid her arm through the diaper bag strap and, in a pirouetting motion, scooped up the baby with the same arm. JoJo giggled. Michelle guessed that by the fifth child, spastic grace just became muscle memory.

Andrea looked at Wu and Patel.

“Has anyone been in the bedroom since you arrived?”

They shook their heads in unison.

“Did you touch anything on either of their nightstands or in the bathroom?”

They shook their heads again.

“Did you call the medical examiner?”

They nodded.

She smiled at the cops. “Look how much better you guys are getting at this.”

TWELVE MINUTES later, the Mercer County medical examiner’s van arrived. Two men from the coroner’s office spoke briefly with Molly. Pretending to be engaged with Brianne and Crystal in an effort to keep Henry and Brett distracted, Andrea had one eye on Molly the entire time. Andrea could tell that not a tear had been shed, but that was to be expected. Molly was rigidly, almost pathologically in control of everything in her life, especially her emotions. Andrea noted a small sore on her friend’s lip, which hadn’t been there when she’d last seen her, the previous week. Had Molly bitten her lip? A concession to the anxiety she must be internalizing?

Andrea had been friends with the other members of the club she secretly called the Cellulitists for about three years. She still thought it was very pithy to combine the word cellulite with elitists to come up with her private hashtag. She wasn’t sure how to properly pronounce the composite word and rarely said it aloud. They had all met because their lives overlapped due to their children’s school or recreational activities. None of the three women were the types Andrea normally would have befriended; then again, she had never really befriended any types throughout her entire life.

Crystal Burns was the gossip of the group, perpetually working her phone like an old line operator from a 1920s movie. She lived by the adage that knowledge is power, but in her case, it was the power to validate her self-worth. She was indescribably insecure, but also incredibly competent. Wanting to know something about everything meant she rarely knew much about anything, so the gossip too often amounted to ephemeral suburban hot air. And yet Crystal was also genuinely warm and caring, and would do anything for anyone anytime they needed it. Andrea sometimes suspected that she was kind for selfish reasons, but the fact remained that Crystal was the glue that held the group together.

Brianne Singer was the closest thing Andrea had to a real friend among the group. She was an interesting contradiction: feisty but timid, nurturing but selfish. Brianne was smart, but she was intellectually lazy, mostly as a result of all the years spent being intellectually lazy. She was selectively fierce and passionate about certain topics, but rarely informed enough to hold her own in an argument.

And then there was Molly Goode. The woman all other women were jealous of. Always put together, but never in a way that flaunted it. Molly was in better shape than you and better dressed than you, her hair was better than yours, and so were her manners. Even her grace in knowing she was better than you was better than the grace you tried to show in knowing she was better than you.

This morning, on what Andrea had to assume was one of the worst of Molly Goode’s life, she looked as upset by her husband’s death as she might have been by running late for a class at YogaSoul.

The doorbell rang again. Molly greeted Detectives Vince Rossi and Charlie Garmin. They saw Andrea over Molly’s shoulder and nodded politely.

With Garmin supervising, the coroner’s assistants bagged Derek’s body upstairs. Rossi walked over to Andrea. She didn’t need eyes in the back of her head to know her friends were all watching the exchange.

Her relationship with the Cellulitists, never warm and fuzzy to begin with, had become more distant since the revelation of her notorious past. Friends, apparently, aren’t supposed to keep it a secret that they have a Wikipedia page under their maiden name. But at least that cat was now out of the bag, since someone had edited her entry and added her married name.

“Please don’t tell me you have a theory?” Rossi smiled grimly.

She smiled. “Not yet.”

Andrea knew that Rossi liked her, but he was also wary of her, as any cop a few years short of their full pension would be. She looked at the glimmer of tension behind his eyes. Andrea knew he was weighing if even she could find a way to turn a heart attack into a murder investigation.

She watched as the ME and the twin paramedics came down the stairs first, trailed by the coroner’s assistants bringing Derek down in a body bag strapped to a stretcher. Patrol Officers Wu and Patel left the house with the paramedics. Andrea glanced over her shoulder at her friends. Crystal buried Brett’s face to her chest to shield him. Brianne placed a comforting hand on Henry’s shoulder as he watched his father being taken away forever. He was in middle school and was trying hard not to break down, but he looked like he’d been hollowed out from the inside.

Molly took it all in with icy detachment.

“You are kidding, right?” said Rossi softly. “About the theory?”

“Sure,” Andrea replied. “I’m just kidding.”

The ME, an Asian woman who worked out of Trenton, signed a form on a clipboard for the surly, burly Garmin, who then went over to his partner. “She thinks it was a heart attack.”

“Damn young for that,” muttered Rossi.

“According to the wife and the meds in the bathroom cabinet, he had a heart condition,” said Garmin, looking at the clipboard. “Atrioventricular septal defect. Congenital.”

Rossi cast a glance at Andrea, waiting for her to drop a bomb on that conclusion.

She said, “I didn’t know about it.”

Rossi nodded, thankful for the limited drama. Unexpected deaths tended to drag a lot of uncontrollable crying out of the families and friends, but this one had almost been downright convivial. The detectives spoke briefly to Molly, explaining to her what the next steps would be, and then they left.

The front door closed.

Andrea wondered for a moment: What would this feel like if it happened to her? After all she had been through in her marriage, what would she do if Jeff died on the way home from work?

Molly came to her and spoke in a soft voice so the others wouldn’t hear. “Can you prevent them from performing an autopsy?”

“Why would they want to?” asked Andrea, but her brain said, Why wouldn’t you want them to?

“Because of his age, I gather,” Molly said. “The men who took him said the medical examiner would talk to Derek’s doctors and confirm his prescriptions before making a decision.”

“If he had a heart condition, then his doctors will confirm it, so I doubt they’d do an autopsy,” Andrea said.

Molly hesitated, biting her lip so that her teeth scraped the edge of the cold sore. With a slight choke, she said, “The thought of him being cut apart just to find what we already know.”

Andrea put a gentle hand on her friend’s shoulder, sensing a vulnerability Molly rarely showed. She said, “I’ll see what I can do.”

* * *

BY TEN a.m., Andrea had lugged a fidgeting Josephine into the West Windsor Police Station. The kid was trying hard to walk these days, which meant she was getting impossible to carry. Each of Andrea’s children had started walking earlier in progression than the previous model, and JoJo was keeping that streak alive.

Ruth, the oldest, hadn’t walked until she was sixteen months. They thought she had motor-neural paralysis, but it turned out she just knew that the second she started walking her responsibilities in life would increase.

Elijah started at thirteen months, but then he’d mostly sat down for the next ten years.

Sarah began at eleven months and was running at a full sprint about a week later.

Sadie at ten months, but that was just to reach the stroller so her mother could push her around.

JoJo began a standing furniture shuffle at nine months and Andrea had mostly spent the past four weeks trying to keep her from hurting herself while she stumbled about like a rubber-suited monster from a Power Rangers episode.

She greeted Tom Templeton, the desk sergeant. After months of visits, he still glared at Andrea like she was a live virus. If she had asked for Garmin and Rossi, he likely would have begrudgingly buzzed her in, but because she asked to see Preet Anand, the new chief of police, he made her wait for clearance.

A minute later, she was walking through the station house. Garmin and Rossi nodded to her as she approached them. Hoping Garmin might have a piece of bagel for her to teethe on, JoJo fussed when Andrea whisked her by. Frustrated, JoJo started her warm-up in anticipation of an Olympic gold-medal meltdown.

Garmin stretched out his massive paws and said, “Hand her over before she forces us to draw our weapons.”

Andrea smiled, always astounded how such a social lout could be so sweet with her baby. Charlie always said JoJo was good practice for when either of his two kids finally gave him grandkids.

JoJo was thrilled to play with the big teddy bear of a man. Rossi, as usual, was happy with whatever kept his partner quiet and kept Andrea moving along, which this did.

She walked toward Anand’s office. Though Mayor Wu had settled on Anand months earlier, the chief hadn’t been officially hired until August. He was young, in his early forties, forceful, commanding, and completely prepared for the job. Born and raised in Illinois, he had a master’s in criminology and had served in the military for five years and then with the Michigan State Police for almost ten. He was no stranger to systemic prejudice and consistently overcame it through sheer hard work and competence.

He checked all the boxes the mayor had needed to fill for a town that was 70 percent Asian and had been underrepresented on the police force for years.

Andrea had been impressed by Anand during the interview process. He might not have small town community policing experience, but he was an agile administrator, smoothly political when necessary, and a truthful boss, and he seemed a sincere family man, all qualities that played in West Windsor.

He greeted her at the entrance to his office and invited her in. She apologized for not having made an appointment.

“This is about the death this morning?” he asked. “Garmin said you were a friend of the family. Heart attack?”

“Looks that way,” she replied.

“But . . .?”

“No buts.” She smiled. “Just asking for the family if there will be an autopsy.”

“That’s up to the ME,” said Anand, eyeing her with growing suspicion. “You know that.”

“I do,” she said. “It’s just . . . Molly is wound pretty tight.”

“I get that, but it’s still up to the ME.”

“I know,” she said. “Maybe I’ll call Jiaying to take the pressure off you.”

Name-dropping the mayor by first name might have worked on the usual rubes, but Andrea realized she had made a mistake when Anand handed her his phone.

“If you don’t know her cell number from memory, it’s 609-555-1414,” he said.

“That won’t be necessary,” she said.

“I know Derek Goode donated five thousand dollars to Wu’s reelection last year,” he said. “And four the time before that. And three before that.”

She put her hands up in surrender with a smile. “Okay, I hear you. Subtlety didn’t work.”

“It might have, if you’d tried it.” He smiled as his phone vibrated. “Excuse me.”

He listened more than he spoke. When he hung up, Anand said, “And look at that, it was a card you didn’t even need to play. Medical examiner spoke to Goode’s doctor and cardiologist. His heart condition was legitimate. Described as ‘a ticking time bomb.’ She’s calling it natural causes. No autopsy.”

“Thank you,” Andrea said.

She started to walk away when he said, “Andrea, since we’re still getting to know each other, for the record, I’ve watched IEDs blow up my friends and I’ve been shot five times, with my vest stopping only three of those.”

He let that sink in for a second.

“You have to come at me with something much better than veiled threats to my job.”

“Filed for future reference, Chief,” she said. “Threats to your wife and kids it is, then. . . .”

“Worth a shot,” he said.

She smiled.

“But one shot is all you would get,” he said.

Then he smiled.

She thought two things: this one might not be a pushover, and he had really nice teeth.

ON FRIDAY morning, Derek’s memorial service was held at the First Presbyterian Church of Dutch Neck, where the Goodes had worshipped. The old white building had been certified by the Presbytery of New Brunswick in 1816. Though Andrea certainly wasn’t one for organized religion, she found a feeling of comfort inside the church, like the first sip of homemade soup.

The walls were cast in soft yellow and white, the pews mahogany. Very modest decorations made sitting in this church feel less uncomfortable for her than sitting in the synagogue when Jeff dragged the family there for show. Maybe because she felt no pressure here? Though she was a very sporadic attendee, the members of Beth El knew that Andrea frowned on religion. The truth was, she just wanted the right to judge everything and everyone around her without fear of being judged herself.

The pastor wore a black gown with a yellow-and-white-striped stole. He was tall, with white hair, and spoke in a soft voice that still managed to resonate throughout the hall as he extolled the virtues of Derek Goode.

Andrea wished she could see more than the back of Molly’s head in order to gauge her reactions to the proceedings. Then she wondered why she had thought that. Molly was sitting in the front row next to her kids. Her brother-in-law, David, sat to her right with his wife, Deirdre, and their two children. Molly’s brother and sister sat in a different row.

“Derek was a lawyer who worked with the elderly, managing their estates and helping them navigate the challenges of age and family security. An avid golfer who claimed a fifteen handicap,” the pastor said to polite laughter from several people in the audience, including Jeff. “An active member of the community, a recreation league soccer coach, and a parishioner in good standing of this church.”

He went on for a few more minutes, all of which Andrea knew was mostly horseshit. Derek hadn’t been a dutiful husband to Molly, because Crystal had long ago gossiped about his affairs; he had been a soccer coach for one year; and most heinous of all, since Jeff always bragged about kicking Derek’s ass on the green, he wasn’t much of a golfer either.

Andrea just chalked it up to the platitudes necessary to ease people through the trauma of death. She saw death as a puzzle to solve rather than a life to celebrate, but the willful sugarcoating annoyed her. Derek and Molly didn’t have a fantasy marriage with wind chimes resonating as they pranced about a grassy field like a pharmaceutical commercial distracting you while the rapid-fire voiceover warned you about side effects like rectal bleeding. Their marriage had gone through the same daily shit as anyone else’s. Derek had been a party boy at work and a softy at home, but Molly made up for any softness on his part by being a hard-ass 24/7.

Maybe that’s what had originally attracted them to each other.

Derek had been a successful lawyer, but he was childish, which was ironic considering his clientele were all elderly. He had been knowingly imposing and forceful in that handsome white-privileged way that most tall, handsome frat bros had. But he was funny and charming, and he had always doted on his children.

On the other hand, Molly was as spontaneous as a cabinet. And ultimately, that’s what she was on the inside as well, a perfectly organized cabinet. Everything in its place and a place for everything. She had been a systems analyst for Wells Fargo before she gave birth to Henry. She was aware of her rigidity, and would joke about it with the Cellulitists but also casually dismiss it as a requirement of her upbringing.

Molly made monthly meal plans. She scheduled all her personal and social activities weeks in advance. She had six-month schedule organizers for her children, but assured everyone she was open to unexpected changes. Molly probably planned the days she would have sex and even the positions they would choose on those days.

Andrea realized she wasn’t judging Molly for that so much as herself. For someone whose mind was so keenly attentive, Andrea’s home life was a haphazard storm of daily drama over where to be, what not to forget, what had been forgotten, and where eggshells needed to be walked on.

Chaos had been her upbringing, but not her preferred default. Andrea’s calmness while standing in the middle of any storm was what had originally attracted Jeff to her. They both had analytical minds, he for numbers, she for people, but Andrea processed information with a studied reserve, while he tended to process in rushed bursts of accelerated activity.

She now studied Crystal Burns, who sat two pews in front of her. Her husband, Wendell, sat at her right, their kids, Malcolm and Brittany, to her left. All were the very model of proper decorum. Crystal had her children well trained, not through a regimen of stern repression, like Molly, but because her kids knew from a very early age that if they didn’t comport themselves, they’d be harangued about it for a never-ending span of time. And not never-ending in kid terms, but literally; Crystal’s ability to fixate never ended.

Wendell looked bored, but then he always looked that way: tired of life and tired of trying not to look tired. Andrea liked him well enough, but as he had worked for the same accounting company since he’d graduated college, drudgery had become embedded into every pore of his skin. Commute to New York, work, commute home, hear about the kids’ boring day at school, hear the same boring complaints from Crystal about the same boring things, rinse and repeat. But he maintained a stiff upper lip about it all, a by-product, she figured, of his New England upbringing.

Andrea turned her attention to Brianne and Martin Singer, who sat in the same row to her right. Their triplets had gone to school for the day so as to protect them from the ugly reality of death. Brianne was more fun than the others, with a crackling, self-deprecating sense of humor, and—kudos to her—she was someone who actively avoided whining about the same things everyone else whined about.

Her marriage to Martin was strained, Andrea knew. Brianne wanted more excitement than he was able to provide her. He had wanted to work in sports management, but ended up managing four assisted-living facilities in New Jersey that were owned by his family. As a result of forsaking passion in his work, Martin had forsaken passion in his life. He was quiet to the point of simulating plaster. Brianne complained that he was barely present for her or the triplets, but Andrea chalked that up to not even being present in his own life.

The Cellulitist husbands, Jeff included, weren’t bad men, just worn down from the burden of the financial responsibilities their zip code demanded of them and terrified of a future that would include nothing but greater financial responsibilities. Ever-rising property taxes, car payments, mortgages, utilities, kids’ activities, and in a few years, third and fourth cars and college tuition.

College. Tuition.

Amazing how one word—greed—could turn those two words into curse words.

Maybe Derek had gotten out while the getting was good, Andrea mused.

She noticed that Josephine, who had been sleeping in Jeff’s arms, had started to rustle. She had sent their four other kids to school because wrestling all of them during a memorial service had not been an option. With all of them in full-day school sessions, life had become a lot easier for Andrea. Even though she still had to pick up Sadie from Montessori preschool at three, Ruth, Eli, and Sarah all took the bus, which meant less running around for her.

Andrea reached for the sippy cup in the diaper bag. Though the hall was warm, the formula didn’t feel too bad. JoJo would likely survive. As the fifth—and absolutely the last—child Andrea would ever spawn, Josephine Esther Stern was already a hardscrabble survivor. Andrea hated Josephine as the choice of name, but since she’d picked three of the four previous ones, she had begrudgingly let Jeff have this one. Josephine had been named after his maternal grandmother.

She never called the baby Josephine, which she knew bothered Jeff. Andrea doubted his grandmother had ever been called JoJo, except possibly a time or two in the backseat of a ’65 Impala, but she liked the nickname because it had a strong Queens vibe to it.

JoJo rubbed her closed eyes with her meaty little fists. The air-conditioning in the hall hadn’t been turned on and the weather had remained in the seventies throughout the week. Andrea hoped the stale air wasn’t going to set the baby off.

JoJo opened one eye. Seeing Andrea looking down at her, she smiled. Her front baby teeth made her look like Bugs Bunny. She was adorable.

“Want me to take her?” she whispered to Jeff.

He handed JoJo to Andrea, who gave the baby her sippy cup. Finally, the pastor’s eulogy ended. He called Molly to the altar to say a few words.

Molly went up with Henry and Brett on either side. The boys were in nice gray suits, which, considering how quickly they had been growing, seemed to have been tailored for the occasion. She wore a black skirt suit with a gray blouse whose color matched the boys’ suits. Andrea mused that Molly looked as impeccable in mourning as she did on any given morning.

Her friend stepped to the microphone and thanked everyone for coming.

“Though this is a tragic shock for many of you, Derek and I had faced the possibility of this happening for years. We knew he had a heart condition, but he preferred we not speak of it. I apologize to all of you for that.”

Andrea glanced toward Jeff. “Did you know?” she whispered.

He sheepishly shrugged his shoulders, which meant he had.

Molly spoke a bit more about the charitable work Derek had done for the church and his unflagging support in helping the elderly as a result of having lost his parents at a young age. She talked about his love for his sons. It was all perfunctory and lacking any real commitment.

Andrea glanced at Molly’s older brother and sister, Jack and Maureen Parker, recognizing them from the lone photo Molly had of them at the house, taken during her wedding to Derek. They were stone-faced in the picture and stone-faced now. But not in sadness, Andrea thought. They looked . . . she hesitated, trying to pin down the right word.

They looked punctured.

Sagging. Deflated. Defeated. Molly’s brother and sister had clearly traveled a different road than she had. Their lower-middle-class Pennsylvania pedigrees were everything Molly had always sought to run away from.

Henry and Brett both spoke next, talking about how their dad had called himself “the human pillow” because he was the one they went to for hugs. Henry’s voice cracked as he fought back tears. The entire hall was silent save for soft sobbing. Molly awkwardly hugged her oldest as Brett quickly joined in, and then together, they stepped off the altar.

The pastor returned to the podium and said, “Thank you for coming to the memorial service. There will be a light lunch and beverages in the fellowship hall. The Goode family welcomes all to attend.”

With that, the service ended. The funeral was planned for Saturday and would be for family and invited guests only. So, small talk aside, that was that. Save for the hushed personal condolences and the sad shaking of heads over a tragic loss, Derek Goode was done.

Life seen through a windshield on Wednesday and in a rearview mirror by Friday.

Andrea picked up JoJo and slung the diaper bag over her free arm.

“I can carry that,” Jeff said.

“It’s okay, I got it,” she replied. “Thanks.”

She wanted to use the baby as her excuse to escape any conversations she didn’t feel like having, which meant any conversations at all.

Over a hundred people had come to the memorial and half of them shuffled to the fellowship hall as the other half slid out of the church to escape. The Burnses came over to Andrea. An overwrought Crystal dramatically dabbed her blue eyes with a tissue that was already smeared by her running mascara. Jeff and Wendell sheepishly shook hands, both feeling some measure of silent guilt for still being alive. Malcolm and Brittany looked mortified by their mother’s drama.

Brianne and Martin came over next.

“You sent your kids to school?” asked Crystal.

“I didn’t want to have to wrangle them during the ceremony,” said Andrea.

“I think it’s important they understand the process of death now that they’re old enough,” said Crystal, adding her usual twist. “And Ruth is older than Malcolm.”

“Ruth helped me investigate a double homicide last summer, so that’s practically like having her mortician’s license,” replied Andrea. Malcolm and Brittany laughed, but were stifled when their mother gave them the stink eye.

The men grunted their way through the small talk while the women waited for an opening to visit Molly, who held court with her boys alongside the pastor and her siblings. Henry and Brett tugged at Molly’s suit coat, wanting to see their cousins and Uncle David.

Flustered by their annoying antics, Molly eventually let the boys go and they rushed to see their uncle. He gave them a huge group hug, but it was the casual glance Molly tossed their way that Andrea noticed. A shade of envy that rarely darkened her eyes. Brianne trailed Crystal, who trailed her kids to the buffet. The men continued their caveman conversation. None of them had noticed the look that Andrea had seen.

She kept her attention firmly focused on Molly.

There was a strain between Molly and her siblings as they chatted. The pastor clearly sensed it, but tried to ignore it while consoling them. The three grew more agitated and the pastor’s overtures became more emphatic. The siblings abruptly left the conversation and actually stormed out of the hall.

The pastor tried to comfort Molly, though she clearly didn’t need it. Even when angry, she remained stoic. Andrea was curious what that encounter had been all about. She knew Molly’s parents had died in a car accident when she was in college and that she didn’t have a close relationship with her siblings. Jack was divorced and childless, while Maureen had never married, so there weren’t nieces and nephews to generate the facile reasons for family gatherings. The excuse Molly always gave was that they lived three hours away in Quaker country. Molly said she had spent too much time and energy trying to get away from there to expend either going back.

Andrea realized she was starting to sweat. She reached around JoJo to get a cloth wipe out of the diaper bag to dab her forehead. As a direct result of JoJo’s fascination with pulling at her curls, Andrea’s mop of hair was now shorter than it had been since high school.

The hall was getting stiflingly hot. How Molly could be wearing a suit jacket and not have a drop of perspiration on her was unfathomable to Andrea. Others noticed her discomfort. Or were they just noticing her? Andrea’s weight loss after JoJo’s birth and the haircut had gone a long way toward alleviating the stares of recognition she’d received around town.

Those first six months after the embarrassing press conference and viral video had been torture for her. Almost a year out, maybe people had just moved on. She hoped so, but the glances now made her question it. Her preference leaned toward being the world’s best but least recognizable crime solver.

Finally, Molly peeled away from the pastor and headed toward Andrea. Her friend was interrupted twice along the way by condolences from other people.

When Molly reached her, Andrea said, “Enough with the condolences.”

“I was tired of them before I heard the first one,” Molly replied. She did appreciate Andrea’s complete absence of bullshit. “This is for everyone else as much as it is for me and the boys, right?”

“I think,” Andrea said. “I don’t have a lot of experience, to tell you the truth. But I know I wouldn’t be able to endure it as well as you have.”

Molly nodded, liking the choice of “endure” to describe it. She looked around the room. “A buffet?” she said. “I mean, it’s just so . . . pedestrian.”

“Hearing Derek had a heart condition was a surprise,” Andrea said.

“It was . . .” She hesitated. “It was something that was always just there. Since he was young. Certainly a part of our lives since I met him. He was embarrassed by it. It was possible he would die from it, but at a certain point, when you haven’t died yet, then it just stops feeling real. Does that make sense? It became no more of a concern than one might have about getting hit by a bus on any given day.”

After a moment, Andrea said, “Have you had time to think about what you’ll do next?”

“Think? I think I will put my husband in the ground tomorrow,” she replied. “And then, I imagine, we’ll all just go on living. What else are we supposed to do?”

She excused herself to greet some people from the church who had been waiting to offer their condolences. Andrea wondered if Molly’s clinical assessment was logic, denial, or willful indifference. When does a naturally reserved and rational disposition step over the line and become pathologically unemotional?

Andrea stopped herself. She was in a bad mood and looking to turn a bad day into something worse than it already was. Molly’s request that she try to bypass an autopsy had begun to rankle Andrea and had her looking for underlying reasons why someone would die of a heart attack. Absurd, but her inclinations always led her to look for a culprit even when there wasn’t one to be found.

She needed to leave. Her habit of dissecting people through observation wasn’t serving her—or her friends—well in this situation. She looked around for Jeff. When some children ran by them, JoJo fussed, wanting to join in. The baby blurted out a frustrated squawk that drew the attention of everyone around them.

Then JoJo decided to double down and let loose with a piercing scream. Her sudden outburst froze the entire hall. Everyone stared with the usual mix of admonition, compassion, and humor.

But it was one look in particular that caught Andrea’s attention. Molly had turned from her conversation to watch an embarrassed Andrea wrestle with JoJo. A look in her eyes hit Andrea like a punch to the stomach. Not annoyance or frustration, not surprise or concern, not sympathy or support.

A look of . . . victory.

It was a look that combined judgment and gloating at the same time. A superior sympathy that the winners of a game always gave to the losers.

Jeff came over. “Time to go,” he stated as much as asked.

“Please,” she said as she handed the baby to her husband. He had a way of calming JoJo down that Andrea currently lacked. She had expected to be impatient with the baby, because honestly, she had never wanted a fifth child. Or a fourth, third, second, or, as much as she couldn’t imagine her life without Ruth, even a first.

Maybe Andrea was unfairly placing the burden of all the opportunities she had lost in life on the baby because she had just gotten a taste of the life she could have had. The previous summer had been the most alive Andrea had felt since college. Which happened to be the last time she had been in pursuit of a killer.

“Should we say goodbye to Molly?” asked Jeff.

“No,” Andrea said, abruptly enough that it caught him off guard. She softened. “She has enough on her plate. Speaking of . . . I can’t eat that buffet. Let’s get Shanghai Bun on the way home.”

As they walked outside to their car, Jeff saw him before Andrea did.

Him.

Kenny Lee.

The intrepid boy reporter, who had been Andrea’s childhood friend and had worked with her to solve the Sasmal murder.

Kenneth Lee, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist in college, perpetual screwup through his twenties, and now, having turned thirty, an unrelenting self-promotion machine. He had parlayed the murder investigation and the turmoil it had caused to the sister towns of West Windsor and Plainsboro into a book deal with Penguin Putnam, a Netflix documentary, and consistent appearances on conservative stations like Fox and Trust News as, of all things, an expert on crime and prejudice.

Kenny Lee, whom Andrea hadn’t seen in three months, since the sentencing hearing for Satkunananthan Sasmal’s killer.

Kenny Lee, wearing a Tommy Bahama black polo shirt with gray slacks and new black Ecco slip-ons. He casually leaned against his eighty-thousand-dollar metallic gray 2021 BMW 7 series and waved to them. She already missed his old Prius.

“What is he doing here?” Jeff asked.

“I don’t know,” she said. “Get JoJo in. I’ll be with you in a second.”

“Hey, Jeff,” Kenny said.

Jeff released some kind of primordial grunt that might have meant “Hey” in Cro-Magnon.

Andrea strolled over to Kenny.

He hitched a thumb at JoJo, whose stubby arms reached over Jeff’s shoulder, clutching air in a futile attempt to reach Kenny. “That one is a lot quieter than the others.”

“You didn’t hear her inside,” Andrea said. She wasn’t interested in banter with him. Their relationship had become strained. In some ways, she wasn’t being fair to him, since her overwhelming desire to avoid publicity was in direct opposition to his desperation in seeking it out.

In his defense, she had read a proof of his manuscript over the summer and he had stayed true to his word and included Andrea more in the book than he ever had in his television appearances. She would always play second fiddle to Kenny when he was the one telling the story, and she knew she had no one to blame for that but herself.

“Why are you here?” she asked.

“Heart attack is what I heard,” he replied by not replying.

“Looks that way,” she said.

They watched Jeff finish up with JoJo. He closed the back door to the Odyssey and then scooted to the driver’s side, keeping a suspicious eye on them the entire time.

Kenny and Andrea looked at each other for an awkward amount of time.

Then, at the same time, they both said, “I think Molly killed her husband.”

ON WEDNESDAY morning, while Andrea and the Cellulitists had gathered in Molly Goode’s house to watch Derek removed in a body bag, Kenny Lee’s day had started as most had over the past few months. He caught the 8:25 a.m. New Jersey Transit express train from Princeton Junction to Manhattan, then walked downtown twenty blocks to Union Square and the offices of Muckrakers Productions, the company that had optioned his book for a Netflix documentary.

He had everything he had wanted for the past several years.

Opportunity. Achievement. Respect.

Kenny had come to enjoy the sights, sounds, and yes, even the smells of the city in a way he hadn’t when he had first worked in Manhattan, after college. For the brief period of time he’d been with the Daily News years earlier, Kenny hadn’t appreciated what the city had to offer. Now fulfilling work with a group of people he actually liked being around had opened his eyes to a lot of things.

Once he had finished the first draft of the Suburban Secrets manuscript in March, Kenny had shifted his focus to the documentary. He had juggled both the book rewrites and the production needs of the documentary 24/7. Though his plate was full, his appetite had only grown. He’d become the Joey Chestnut of typing, a yawning maw that no amount of work could fill.

He stopped at the Starbucks on Broadway and Sixteenth and got coffee for everyone. He liked this Starbucks more than the one on Fourteenth or the one on Park and Seventeenth and definitely more than the one on Twelfth. He smiled as he paid for the drinks. Imagine Kenny Lee buying coffee for his crew, much less Kenny Lee having a crew. And most unbelievable of all, Kenny Lee remembering what his crew’s regular Starbucks orders were.

New Kenny would have broken into a spontaneous Gene Kelly sidewalk dance if Old Kenny wasn’t keenly aware that he’d trip and drop the coffee tray.

Kenny passed the Staples office supply store and entered the small, nondescript lobby at 9 Union Square West. He nodded good morning to Carlos at the small security desk and lucked into an elevator waiting for him on the ground floor. He walked through a large open office space on the fourth floor to the back, where the Muckrakers sublet from the computer-analyst-software-developers-who-knows-what-the-hell-they-do company that leased the floor. It was an open L-shaped floor plan and their production company leased the back of the L between the kitchen area and a large conference room.

Kenny couldn’t wait for them to have their own floor, then their own building. He chided himself for thinking that way, since he had no ownership stake in the production company. He’d been without a sense of purpose for so long that he craved the friendships and mutual goals, but he had to constantly remind himself to keep it at arm’s length. He was a contract player, and when the job was done, Muckrakers Productions could just walk away from him.

Business hours were technically ten to six, though as with everything in the digital age, work was expected out of you seven days a week with an extra dollop of guilt thrown at you by your corporate masters for not defying time and inventing an eighth day. Even getting to the office twenty minutes early, Kenny was the last to arrive. Jimmy Chaney, his friend from West Windsor, greeted him. Jimmy rode in from the same station as Kenny, but he usually took an earlier train. The Kenny Lee of a year ago would have been insecure about that. The Kenny Lee of today was glad to be a part of such a motivated group.

“What’s the day looking like?” he asked as he put the cardboard tray down on a counter across from the desks. The counter ran underneath a row of windows that looked out over an alley between the backs of buildings and had become piled with excess office crap.

Jimmy grabbed the closest cup. The athletic African American had been, until a few months ago, a cable-line operator for Xfinity in Mercer County. He had helped Kenny and Andrea on the murder investigation the previous summer. When Kenny signed the Netflix deal, he had brought Jimmy along as his jack-of-all-trades, assistant, and cameraman.

Jimmy handed the cup he’d grabbed to Shelby. The fifty-one-year-old Shelby Taylor had served in the City of Charleston Police Department and was now a private investigator, kept on retainer by Muckrakers’ parent company, the WWF Group. Wolfe-Weber-Fischer was considered a small multimedia conglomerate and had established Muckrakers, among dozens of other similar entities, as a production-specific LLC for Suburban Secrets.

Wearing a tight dark blue T-shirt and tight faded jeans, and with blond hair she assured everyone was natural, Shelby looked more like a former surfer than a former cop. But she was in better shape than Kenny and Jimmy combined. And Kenny conceded Jimmy accounted for 86 percent of that group total.

Jimmy passed a chai to Sitara Sengupta, their boss and supervising producer for the Suburban Secrets documentary. She thanked him and took a sip from her tea before running down the day’s agenda. The thirty-one-year-old Indian American had thick black hair that was tied back in a hair band. She wore a loose-fitting Muckrakers T-shirt and casual brown linen pants with vintage beige suede ankle boots. She was an organizational savant who also had the ability to recognize the emotional core of any moment captured on camera. She was also Kenny’s girlfriend. He was afraid that even thinking of that word might make it fall apart in the real world, but after a few months of active dating, this was as close as Kenny had come to a girlfriend in years. And years would be measured by the thirty he had existed on the surface of the planet.

As Sitara talked about administrative details that didn’t interest him much, Kenny was distracted by a notification on his phone. The West Windsor Police Department had responded to a 911 call. He recognized it as the address of Andrea’s friend, Molly Goode. Kenny noted that the medical examiner had been called in, which meant someone there was dead. He smiled when he saw that Officers Wu and Patel had been dispatched. He hoped for their sake it was death by natural causes. He had interviewed Molly for the documentary, but she’d been so stiff on camera that Sitara had cut all of her footage.

Pretty early in production on the documentary series, Kenny found the interview process to be his favorite part. He liked the Q&A. He liked the opportunity to hold people accountable for their mistakes on camera and he liked giving the people who had helped in the investigation their due. Building the story visually was quite a different experience from how he’d wrestled his newspaper articles and his book manuscript into shape. Ultimately, though, it was all storytelling, and Suburban Secrets had a great story to tell.

But something had been nagging Kenny for weeks and he had refused to listen to its whining chirp. He had ignored it not because of the workload of the documentary, or the book’s impending release, or because his relationship with Sitara had entered new territory for him. He ignored the annoying pull because giving it voice might ruin the streak he’d been on.

Snapping himself out of his reverie, Kenny abruptly said, “I need to drag Jimmy to a meeting.”

“Book meeting?” Sitara asked.

“Yeah,” he said.

“I do need him here,” she said.

Willingly entering into the passive-aggressive tug-of-war, Kenny said, “I’m paying half of Jimmy’s salary out of my own pocket, so half of his time is mine.”

“I’ll give you the top half ’cause my face is so pretty,” Jimmy said to Kenny, then turned to the women. “But I’ll save the lower half for the ladies, because, based on all my Yelp reviews, that’s the part most people prefer.”

Shelby bounced her empty cup off Jimmy’s head. Any potential argument between Kenny and Sitara had been thwarted.

“That’s the way the day shapes up, then,” said Sitara. “I’m editing. Shelby will do whatever Shelby does, which in my experience has been . . . whatever Shelby wants to do.”

“Today I’ll be pounding the pavement far and wide for a slice of authentic New York Sbarro’s pizza,” Shelby interrupted.

“You’ve lived in Brooklyn for three years. The hillbilly act doesn’t work.” Sitara continued, “And . . . Jimmy and Kenny are off to ensure Kenny’s ego remains well fed.”

Grabbing the four-thousand-dollar Sony PXW-FS5M2 4K XDCAM camera that Kenny had paid for, Jimmy tapped Kenny on the shoulder and said, “We all know how hungry that beast is. Where we going first?”

* * *

THEY WENT uptown to the offices of United Talent Agency to visit Kenny’s book agent. They met Albert Lŭ for an update on the book’s preorders and the cities that Putnam had finalized for the publicity tour. Though Albert hated it, Jimmy filmed the meeting for Kenny’s YouTube channel. Kenny was torn between promoting his own brand and still needing platforms like Putnam and Netflix to make him legitimate to a wider audience. And, gun to his head, Kenny couldn’t verbalize what the end goal of all his self-promotion truly was, since he didn’t have a personal agenda other than wealth and fame, and maybe not even so much wealth.

But still . . . the nagging buzz in the back of his mind wouldn’t go away.

Their next meeting was with Digital Partners, the publicity agency Kenny had hired to help separate his own interests from those of his corporate partners. They were all about clicks and likes and views as if they were tangible things, but those meant significantly less to Kenny than things of substance, like wealth and fame, and maybe not even so much wealth.

Afterward, they returned to the Muckrakers office so that Jimmy could lock up the camera. Jimmy hadn’t trusted Kenny even with the combination to the safe lock, much less with carrying the expensive equipment around the city. He said his goodbyes and left for the day, heading back to Penn