9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

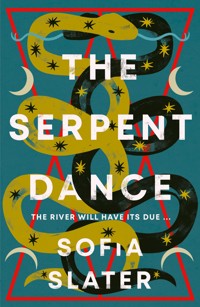

'The Wicker Man meets Rebecca, with darkly beautiful surroundings and mysterious, brooding locals - this is the perfect summer holiday read' Fiona Leitch, bestselling author of the Jodie 'Nosey' Parker cozy crime series 'Intriguing contemporary whodunnit … profoundly unsettling' Crime Fiction Lover 'The Gothic environment, at times evocative of some of the tales of Daphne du Maurier, is powerfully etched' Crime Time IN THE HEART OF CORNWALL, A MURDEROUS MIDSUMMER BEGINS ... At midsummer the Cornish villagers of Trevennick dance around bonfires and make offerings to the river. It's not the sort of thing that appeals to Audrey Delaney, who is very much a city mouse. But when her (sort of) boyfriend Noah whisks her away on a surprise trip to the West Country, she's determined to do the best she can to enjoy herself, if that's what it takes to remove the question mark from their relationship. Then their first night ends in tragedy, and Audrey finds herself embroiled in a police enquiry and unsure who to trust. She'll have to untangle the mysteries of this insular community quickly, though, because people are dying fast. THE RIVER WILL HAVE ITS DUE ... READERS WHO JOINED THE DANCE - 'I loved the mix of old folklore/rituals, (giving off The Wicker Man vibes), with a locked door mystery, that I didn't expect … phenomenal' - 'One of my favourite books of the summer … really excellent' - 'Perfect midsummer read' - 'This book had me quickly turning the pages, eager to know what might happen next' - 'I was instantly hooked … Add this to your TBR!' - 'An atmospheric tale that kept my attention from start to finish'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 282

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

For Trixie Chalevant

Dhe’n gwer yn hans kerthys’vy

Ha’n gorthewer tek dhe’m brys;

Yn le may whelyr mowysy,

Ow quary dro tansys.

Curunys yu my metheven,

Mar gough gans y wyluen;

Dres pup pras ha blejyewen’

Gans whekter a dhenew.

…

Yn boreles war’n glaston-ma,

Aga hus a ransons y,

Erbyn dos dewyn kensa,

Ha’n jeth ow colowy.

*

As I walked out to yonder green,

One evening so clear,

All where the fair maids may be seen,

Playing at the bonfire.

The bonnie month of June is crowned

With the sweet scarlet rose,

The groves and meadows all around,

With lovely pleasure flows.

…

All on the pleasant dewy mead,

They shared each other’s charms,

Till Sol’s first beams began to play,

And coming day alarms.

Friday

Chapter 1

With hindsight, she could see that the whole set-up was an invitation to bad luck. They wouldn’t be able to get away for their first anniversary – that fell during a major new install at Noah’s gallery – and he wanted to make it up to her. So they were popping the champagne a little early, with a long weekend away after ten months together, location to be revealed.

Never celebrate something before it’s happened.

At the time, though, she’d been excited, and happily set about proving to herself that they were, as she hoped, going to Paris. It was the obvious choice: within easy reach of London, and full of museums – trawling through museums and galleries already being how they spent most of their weekends. She’d never been, in spite of how close it was, and Noah knew it was on her bucket list. She found the epithet reassuring, too: the City of Light. No night-time panics likely there.

Not that she’d voiced this to him explicitly. But she’d dropped hints. And he’d smiled knowingly every time she teased him about the surprise, clearly certain she’d be happy with what he had planned. She was sure it was Paris, and, for a few weeks, she spent the time she should have been working on illustrations for the new book staring out of the window instead, blind to the bus stop and the overflowing bin that made up the view. She saw instead her and Noah feeding each other little forkfuls of something buttery at a bistro, their table overlooking a cobbled square. Her and Noah crossing bridges arm in arm, while an accordion played faintly in the background. Her and Noah being visibly in love. Paris would make it obvious. Paris could make it certain.

She couldn’t get to sleep the night before they left, and stayed up late double-checking her passport was in date and trying to decide which little silk scarf would look most French when tied around her neck. She chucked a fresh sketchbook into her bag too; lately she’d been a little lazy about keeping her sketch diary. All the drawing she did was for work, and she was feeling stale. Paris would surely refresh her creativity, with its gorgeous architecture and decadent food, not to mention the Louvre, the d’Orsay and all the romantically bare garrets once home to artistic greatness.

Still dreaming of oozy cheese and floodlit churches, she woke early. A last check of the luggage, a last look in the mirror. A faint hope that she’d have transformed, overnight, into someone who looked the romantic part. But no, hers was still just a presentable face: dishwater hair cut in a fringe, hazel eyes, cheeks tending to the round. Ah well. Beautiful or not, someone was still taking her to Paris for the weekend.

Noah picked her up in a cab, and she leaned in for a long kiss, blushing a little when he looked bemused. She wasn’t usually one for public displays of affection. But the taxi turned west, not north towards St Pancras, and a faint shadow of misgiving fell over her heart. ‘Where are we headed?’ she asked Noah.

‘Patience, patience,’ he replied, coy, still playing the romantic game. She tried to smile back, to keep the flirtation going. But when they got out of the cab at Paddington and Noah pulled two tickets to Cornwall out of his pocket with a flourish, she couldn’t help but feel crestfallen. She could tell from the disappointment in his face that the disappointment in hers was hurtfully clear.

Settled in their seats on the train, she tried to improve the atmosphere, chattering as she unpacked the sandwiches he’d bought, cheerfully reading out crossword clues. But her heart wasn’t wholly in it. The truth was, she hated the countryside, and she resented Noah for not knowing this. Also, she’d put so much effort into believing what she wanted; she felt stupid, and resented him for that, too. She might have been happier with Cornwall if she hadn’t expected Paris.

Noah must have been able to sense the insincerity of her smiles, because he barely responded to her, just yanked the culture section out of the paper and fixed his eyes on the reviews. Audrey watched from the window as London petered out around them, and, remembering last night’s excitement, felt a tiny bit like crying.

Occasionally, with Noah, there were these… gaps. They’d met ten months ago, both swiping to match, and at first she’d felt wildly lucky. Finally life seemed to be turning into what it was always meant to be. He was ostentatiously good-looking, with high cheekbones and glossy dark hair that fell over his forehead. She started sketching that perfect face now, in the margin of the paper, cross-hatching a shadow to bring out his full lower lip. It was sometimes a source of worry, the distance between them in this regard. He was markedly beautiful; a little skinny maybe, but that fit the part – an art world denizen, stick-thin and draped in beautiful clothes – whereas Audrey had long ago admitted to herself that she was entirely average. Which wasn’t to say she couldn’t brush up nicely. But her prettiness ebbed and flowed depending on things like her mood, the time of the month or the effort she’d put in on a given day, whereas she’d never been out with Noah and not seen someone, man or woman, checking him out. Nevertheless, he seemed to find her plenty attractive, and the sex was good. Good enough, anyway.

And they had plenty in common professionally. They might be playing in different leagues, but the sport was the same. Noah worked in a big-name gallery, the kind where he and all his colleagues wore black and got invitations to private views and VIP openings at art fairs and museum retrospectives. Audrey toiled at the more commercial end of the art world, in graphic design and illustration. It had been the practical option; she had needed to make a living straight out of university and had started freelancing several years ago while she was still a student on the sensible, useful graphic design course her parents had pressured her to choose over art college. There had been no funds and no time for experimenting or waiting-and-seeing-how-things-go, but she’d never let go of her childhood dream of being an artist. A real one. Who drew and painted things because they haunted her head, not because a textbook needed a diagram of the kidneys, or a new restaurant wanted a logo.

She couldn’t deny that the world Noah gave her access to had been part of his attraction. At the start, she’d pictured them together at all those private views. He’d introduce her to his colleagues, and they’d laugh together over wine, and she, too, would be dressed in black and wearing interesting jewellery. Maybe, eventually, she’d show him some of the work she did for herself in her spare time, and he’d be amazed, and want to show her at the gallery, and her whole life would be different.

So far it hadn’t worked out like that.

He did take her to gallery events at first, and she did drink the free wine, but she never seemed to say quite the right thing; his colleagues gave her thin smiles and found ways to leave the conversation. Most of the time, Noah didn’t want to go to openings. ‘Done one, done them all,’ he said whenever she asked. So now they spent more evenings in than out, with a takeaway and the telly. Like anybody, Audrey thought. But she wanted to be somebody. When she’d dug what she thought of as her ‘dark drawings’ out of a drawer and showed him, he just nodded slowly and then turned to the commissioned illustrations scattered across her desk, picked one up and said, ‘I love this, though!’ It was a drawing of a dodo.

That wasn’t a problem. It wasn’t that she wasn’t in love with Noah. He was the handsomest man she’d ever get the chance to be with. It was just… these little gaps.

And, oh God, there it was, on the train, that stupid dodo, staring at her from across the aisle. She prayed Noah wouldn’t notice and fixed her eyes resolutely on the fields, cows, hedges, fields which had repeated endlessly since they exited the London sprawl.

‘Look, Audrey, it’s your book!’

She gave a tight smile to acknowledge he’d spoken, but said nothing in reply. Her turn not to play along with his attempts to cheer her up. He was oblivious, or pretended to be.

‘Excuse me. Excuse me? My girlfriend illustrated that book,’ he said, leaning across the aisle, gesturing at Audrey and giving a full-wattage smile to the mother who was holding the book open, pointing out the different animals to her toddler. All he got in return was another vague smile and nod. She was clearly more concerned with keeping her kid quiet than with meeting the book’s creator.

‘Stop, it’s embarrassing,’ said Audrey in an undertone.

‘What did The Times say? “Equal parts urgency and enchantment”? Baby, it’s brilliant. You should be proud!’

‘I was just working to a brief.’

‘Come on! Every time I see that dodo, it makes me smile to think you drew it.’

She shrugged and turned back to the cows, hedges, farms, fields. Noah raised his hands in a little gesture of exasperation, and the strained atmosphere descended again. When she was sure he was looking away, Audrey began to obliterate the drawing she’d done of him next to the crossword, scratching it out one heavy line at a time.

He had quoted correctly. Equal parts urgency and enchantment. The book, a children’s compendium of extinct species, had recently been released and was selling unexpectedly well. With barely any text, just the names and death dates of a series of animals, along with a few facts about each, Audrey’s illustrations had been given all the credit for its success. She thought it was more down to humanity’s rising ecological panic than her drawings, but the upshot was more attention for her work than ever before.

The trouble was, it was the wrong kind of success. She tried to see it like Cornwall: the problem was her expectations, not the situation. There were definitely perks – she liked having money in her pocket for the first time – but she also felt further than ever from the serious artist she’d always dreamed of being. Everyone now thought of her as a charming children’s book illustrator. Once you had a reputation, she worried, it wasn’t easy to rewrite it.

Then, too, there was something hollow about success when you didn’t have anyone to share it with. She had Noah. Except it never quite felt like they were on the same hilltop together, taking in the same view. Her family: better not to think of them at all. And most of her friends, she was beginning to realise, were really acquaintances whose congratulations meant little to her. The more praise the book received, the more she felt alone.

The project had been a last-minute commission when the first illustrator dropped out, and she’d dashed off seemingly hundreds of dodos, thylacines and great auks in a matter of weeks. She’d enjoyed herself, but it was just another job, another number of pictures to get through. Now that it had done so well, they’d signed her up for a second one, a kind of atlas of endangered Britain, from hedgehog to hedgerow. Those drawings had been due last week, but she had yet to even begin, and her publishers had started asking her when they’d see the first drafts – politely so far, but with an unmistakably anxious frequency.

She had told Noah how she felt, but there again, a little gap had appeared.

‘What’s so wrong with success?’ he’d asked.

‘It’s not about success, it’s about identity,’ she’d replied. ‘It’s how I want to be defined. I’m always going to be that girl who drew the cute dead animals.’

‘Grass is always greener. The up-and-coming artists I work with would kill to have some cash and name recognition. You should be grateful!’

She hated it when people told her she ought to be grateful. Even when they were right. Gratitude seemed to be an emotion you never felt when you were meant to. Like this trip; Noah had arranged everything, paid for it all. And all she felt was disappointment.

They pulled into a station: Exeter St David’s. She stared out at the crowds shifting and waiting under the green platform roof. Maybe she should just get out here and head back. It wasn’t only the disappointment and the strained atmosphere that were getting to her. It was the knowledge that the sun would go down and there would be no streetlights to mitigate the dark. In the countryside, night was night.

Noah had never complained about her leaving the blinds open while they slept. It was one of the reasons she liked him. But he’d probably been oblivious. And she hadn’t exactly wanted to make things explicit. You know how small children need night lights? Same deal.

She’d spent too long thinking about it, and now the train was pulling away from the platform. Looked like she’d have to put up with a couple of dark country nights. She didn’t want to admit how uncertain she was that she could endure them.

After Exeter, she forced herself to make an effort.

Tea arrived, dispensed from a cart pushed by a man in a green waistcoat. She ordered two, and two slices of fruit cake wrapped in plastic, handing one to Noah with a conciliatory smile. She pushed croissants dipped in café au lait from her mind. As the man handed over the cardboard cups, some of the scalding water leapt out from an insecure lid, splashing over Noah’s fingers. He winced and she reached out, dabbing at his hands and clucking in concern. ‘You okay?’

His hands closed around hers and she looked up to see him smiling at her, his perfect smile. She returned it, sincerely, for the first time since they had got on the train.

‘So tell me about the place we’re going.’

‘Deepest, darkest Cornwall.’ She tried not to wince. ‘Some village near the south coast. They have this midsummer festival, left over from pagan times, a really authentic celebration, you know? Costumes and bonfires. You’re always talking about how dull the country is.’

‘So you wanted to prove me wrong?’ She said it lightly, giving him the chance to take it as flirtation. His smile indicated that he had. But once again she was disappointed: of what she’d shared of her childhood, he’d retained only the word ‘dull’, the sense that she’d fled boredom, nothing darker. Stop it, Audrey, she told herself. She’d never made it more explicit, so he couldn’t be expected to understand. And yet didn’t love mean crossing that gap sometimes, being able to understand things even when they weren’t spoken?

Then, something extraordinary. The train broke out right next to the sea wall, running parallel to the shore only a few metres away. The waves must come right up to the tracks in a storm. Out on the sun-sparking water, sailing boats tipped this way and that. Red rock outcrops thrust up along the beach, and between them families were engaged in a laughing struggle against the breeze and the gulls, arranging rugs and umbrellas, protecting their picnics. It was beautiful.

‘Is this why you think I should get out of London more?’ she asked, nodding at the panorama.

‘Magical, no?’ He flashed The Smile. ‘I came once as a kid. I never forgot it.’

‘So we’re recreating a childhood holiday?’

‘Not exactly. My parents and I stopped in Devon. We’re going further.’

She tried to imagine wanting to return to any of the scenes of her childhood. Noah was adopted, something he’d told her without looking her in the eyes; there was hurt there. But from the sound of it, his parents were lovely people, kind and generous. They’d supported him for his first few years in London, letting him figure out what he wanted to do. She hadn’t said, It’s not always worth knowing your real parents.

‘Where’d you hear about the festival?’ They were pulling away from Plymouth now, crossing into Cornwall. The sea wall was far behind them now, the endless roofscape of the city’s terraced houses all that was visible from the train.

‘Oh, just around, you know.’ He waved his long-fingered hand vaguely, suggesting a swirl of information in the air, waiting to be seized. His knee was juddering, she noticed, and the hand, once it had completed its gesture, descended to tap an anxious rhythm against the moulded plastic of the table.

‘You seem kind of edgy. Is everything all right?’

‘Just impatient. Hate trains. We’re getting close.’

‘Should I be nervous too? You said this festival had pagan roots. Will I have to climb inside a wicker man when we get there?’

He didn’t pick up on the joke. ‘It’s actually wicker animals here, not wicker men,’ he said earnestly.

Noah seemed distracted for the rest of the journey, tapping fingers and feet, staring fixedly out the window. They weren’t that close yet; there was still the change to a branch line ahead of them, over an hour to go. In the silence, it occurred to Audrey that she ought to let someone know where she’d be all weekend. She’d let herself get carried away with the idea of Paris, and had told everyone like it was a certainty. But when she got out her phone to send a text, there was no service. Ugh. The countryside. She turned to the window and shut her eyes against the strength of the summer sun, trying not to think about how she’d feel after it went down.

Chapter 2

There was a taxi waiting for them at the station. But a taxi without a driver isn’t much good. They stood next to the parked car, looking around with a mixture of hope and impatience. ‘Are you sure this is the one you booked?’ asked Audrey.

Noah didn’t appreciate the question. Of course he was sure. Trevennick Taxi, it said, right there on the side. Silence fell, the same miserable-but-not-admitting-to-it silence that had prevailed on the train. Noah stood tapping his phone in a private bubble of exasperation. So they wouldn’t be sharing this trouble. Fine. Audrey waited for him to resolve the mystery and gazed around at the station and its environs. Only a few passengers had got off here, all greeted and driven away. Now the roses and pansies in tubs along the platform were nodding in the heat, their rhythm slowing as the air stirred by the train’s passage went still. Audrey traced a few lines in the pollen and dust on the taxi’s windscreen: swipe, swipe, dot, squiggle, and she’d made a snake sticking out his forked tongue at the scenery.

The station was tucked into a little cleft between hills. Trees crowded dark on each slope. A bent iron gate gave access to the nearest wood. The reclined angle and patches of rusty moss told the story of a long, losing battle with time. The trees behind the gate grew close, blocking all the light; Audrey couldn’t imagine anyone choosing to walk there.

Here the heat was heavy, far heavier than it had been in London, and loud with bees and birds. She could feel it descending on her, as thick and yellow as the pollen on the car. She could almost fall asleep here, leaning against the taxi, watching those woods behind the gate. They needed watching. Something looked liable to slither out of the shadows, into her dreams. She stared deeper into the trees. The shadows looked wrong somehow. As though they were darker than they should be. Or greener. She took a step forward, for a better view. The dark behind the gate seemed to bulge slightly as she stepped towards it. The way it moved seemed unnatural. Like the snake she had just drawn had leapt into being and was writhing slowly through the hot dark.

A door slammed behind her, and she jumped and turned at the sound. ‘They take their time down here, I guess,’ said Noah with a tight smile at her, as though she’d been the one sighing and chafing at the wait.

The station cafe was in a little hut perched above the platform, and now a man was coming down the stairs, raising a hand in their direction. The taxi driver, she supposed. She looked back at the forest. Nothing. Too long staring at the passing scenery from the train must have tired her eyes.

Now she took stock of the driver as he came towards them, unhurried. He was black, with shaggy hair rusted gold here and there by the sun. About the same height as Noah, he was equally well endowed as far as cheekbones and full lips went, but with an easier smile and very different clothes: a loose old shirt and jeans, worn in and faded like his curls. Nothing like Noah’s precise trouser cuffs and expensive wool sweater – wasn’t Noah hot in those? Next to the man’s heels a broken-coated dog the colour of bleached straw was trotting, tongue lolling in the heat.

Nearing them, the man stuck out a hand. ‘I’m Griffin, hi.’

‘We’re going to Trevennick,’ said Noah, ignoring the hand. ‘I booked. Did you get the time wrong, or decide to stop for a coffee?’

‘More of a tea drinker really,’ said Griffin, smiling at Audrey, who dropped her gaze. ‘But no, I work in the cafe there, just needed to shut up shop.’

‘Right, well, shall we get going?’ said Noah, unmollified.

‘Don’t worry, village’ll still be there.’

Audrey was grateful she was still looking down; it made it easier to tuck her smile out of sight. When she looked up, Griffin had noticed the snake she’d drawn on the dusty windscreen, and he smiled at her when she blushed.

Into the car: bags piled in a muddy boot, and an apology for the dog hair. The dog itself went in the front seat. Again, Audrey had to suppress a smile as Noah began fastidiously picking hairs from his long legs while the dog stared back at him with an open, panting mouth. She felt a bit disloyal.

Then they were away, hurtling down steep-sided lanes. When they had to pull into a passing place to let someone by, Audrey spotted small purple flowers and heavy-headed grasses growing from the stacked stone walls. Then, off again. They were rattling over roads full of sudden dips and steep climbs; the breeze through the windows was a relief in the heat, but the speed and the stone walls pressing close to the car were frightening. Where the stone gave way to hedge, twigs whipped at the open windows and scraped at the doors, small reaching cousins of the menacing wood. Audrey hoped every turning was the last, but the alarming drive continued.

‘So you’re down from London then?’ asked Griffin, eyes on them in the mirror as they whipped round a sharp bend.

Audrey, clenching the door handle, managed a ‘Mm.’

‘Staying in the big house?’ Still his eyes were on her in the mirror. It was a bit worrying; she could see a tractor coming.

‘Is it that big?’

‘Size matter to you?’ His grin got bigger as he said this, still looking into the mirror, not at the road. He changed down a gear and pulled out of the tractor’s way just in time. It rumbled past, twice as high as the car and carrying some sharp silver attachment on the back, whose many points jutted at them through the window. When they were under way again, he gave a more direct answer: ‘It’s not enormous, but it’s where the local squires used to live, in the days when there were such things. Lots has changed since then, but round the village we still call it the big house.’

The village began to gather but took a while to cohere. A farm stood proud of its steep fields; over the next rise a few houses were strung along the descending road. Griffin had slowed now, and Audrey had time to take in the houses, some withdrawing into the trees, built half into the hillside, like caves that had acquired a civilised front. There was something secretive about the landscape, all those buildings standing apart from each other, tucked into slopes and woods. Everything was made of stone and had small windows. She thought of the farming families who had lived in such places a century ago, cut off from everything but the land, isolated behind their thick walls. If something went wrong behind walls like that, how would anybody know?

She shivered, and as she was shivering, she spotted the snake and nearly screamed. She immediately felt silly; it was only a sculpture, stood by someone’s garden gate. And she was in a car! What harm could it do her? And yet she did feel obscurely harmed, or, if not harmed, vulnerable. As though the snake – a creature she had just doodled, had thought she’d seen in the woods – had been placed there as a message to her specifically. We see you, it said. But this was stupid. She was tired and out of her comfort zone. It was nothing but a garden decoration, some bit of village hall arts and crafts. It was about shoulder height, woven out of thin branches. The word withies popped into her head, but that might be wrong; she was no outdoorswoman. They drove on and she tried to put it out of her mind.

A few garden gates later, there was another sculpture, of a curly-horned ram. And then two more a bit further along, a horse and a bird, though the bird looked slightly wrong, as though it had borrowed some of its parts from a fish. She supposed withy wasn’t a medium that allowed for much accurate detail. Still, the strange bird was a bit unsettling, the way a child’s drawing sometimes ends up accidentally ominous. Despite the heat and the little beads of sweat standing on her lip, she felt a shiver. She cleared her throat. ‘Those animals…’

‘You mean the obby osses?’ replied Griffin. They must be for the festival Noah had mentioned. The blonde dog stared back at her, panting hugely as though laughing at her. She was being ridiculous.

But before she could finish reassuring herself – or ask what ‘obby oss’ meant – there was the grind and screech of the taxi as Griffin pulled to a sudden halt.

A commotion in the churchyard. Among the yews and gravestones, a man and a woman stood arguing. There was a yellow haze to the air from the heat, pollen and road dust. The thickened distance seemed to slow and distort their shouts and gestures. She felt as she had looking into the forest, only now the confusion was caused not by darkness but by light. The shadows cast by the people in the graveyard weren’t behaving as they should.

‘Tain’t right,’ the man said, while the woman, red-faced, reached up to grab his strident hands. He thrust her away angrily.

‘Oi, Trev,’ called Griffin. ‘What’s up?’

The man had been facing away from them, but as he turned, she saw why Griffin had intervened. They were obviously brothers, though Trev appeared to be a few years older, and a good bit surlier. His lips curled into a snarl, rather than a smile like Griffin’s.

‘Drive on, Griff. ’Sall right.’ He was controlling himself in front of strangers, but his chest was rising and falling quickly.

The woman’s eyes darted nervously between Trevor and the taxi. She called out, in a voice strangled by forced cheer, ‘Have you got the Trevennick House visitors there? Welcome to the village! I’m Lamorna Pascoe.’ She gave a little wave. Her expression was worried, embarrassed, but not rageful like her companion’s. Her thin blonde hair, cut to chin length, was sticking to her cheeks in the heat. She was all in black, and, Audrey now noticed, wearing a dog collar: the vicar.

Griffin hesitated, but then another car pulled up behind, braking sharply, and the driver leaned out to shout at them, ‘You’re gonna die!’

‘What did he just say?’ asked Audrey. The driver had a thick accent; she was hoping she’d misheard.

‘He’s suggesting I learn to drive.’ Griffin stuck his hand out of the window in a placating gesture; after another jerk of the head from his brother, he put the car back in gear and pulled away. Audrey turned around, and saw the pair watching the receding taxi. The sun was behind them, and she could only see their dark, hazy shapes.

‘Wasn’t expecting a welcoming committee,’ said Noah, drily.

‘First time there’s been paying guests up at the big house,’ replied Griffin, in an absent tone that indicated his mind was still on the argument they’d witnessed. ‘Talk of the village, you are.’

Audrey and Noah shared a look of discomfort at this idea. Immediately she felt better. That little glance of complicity reminded her that they had been together a year – well, nearly – for a reason. She liked him. They belonged to the same world. The gaps were bridgeable. She was annoyed that her eyes kept meeting Griffin’s in the rear-view mirror.

Now they were past the church, the village began to gain mass and density. A couple of smaller streets wound up the hill away from the river. The houses were side by side here, but they still had the isolated look of the scattered farms; the tiny windows set deep in stone walls had an ungenerous air, like they were designed only for looking out, never in. It was a sunny summer afternoon, but all the buildings seemed to retreat into damp green shadow. They rumbled over a narrow bridge and passed a pub, a post office, a village green. Here at least it was open enough for the afternoon light to spread itself around. On the grass, people were standing and building something out of the same materials that had been used for those midsummer creatures. They stopped what they were doing and turned to stare as the taxi drove past. Audrey wondered if the whole weekend would be like this, everyone watching wherever they went.

The village was all old stone and mossy roof slates, twisty corners and climbing roses. Audrey thought of the brief for her follow-up. How had Jemima at the publisher’s put it? ‘Something about the vanishing creatures of field and hedgerow, you know, Beatrix Potter but with science, a piece of English nostalgia for kids who’ve always been online.’

As they passed through the village, she took mental snapshots to sketch later – this setting was exactly what they were after, though she’d have to brighten it up, make it charming. She supposed she should find it charming. But it felt… hostile.

They pulled away from the houses, following a road parallel to the river, which climbed higher as the channel cut by the water deepened. The river widened as they went, heading towards the sea, becoming more clearly an estuary; she could see plastic buoys bobbing orange in the water. But the forest hadn’t given way. Trees crowded close here and on the opposite bank. Even rushing past in a car, she didn’t like to look into the darkness between their trunks.

Still, the place was beautiful. The sun bounced off the water in fat, slow slabs, and bronze reflections slid around on the river’s surface. The birds were the only things in the whole scene moving in any kind of hurry. Seabirds, she thought, all winging inland with swift determination, though the shore was a few miles distant. She went to point them out to Noah, but as she did so she noticed his face and fists, both clenched. He stared out of the window with tense and avid eyes, scanning the water and the treeline, as though they were withholding something from him.

‘Are you all right?’

His response was slow, and more than a little false when it arrived. She watched him unball his fists, work his jaw loose, apply a smile. ‘I’m great! Just looking out for spots I recognise.’

‘Sure?’

‘Yeah. So excited to be here.’ He kept his head turned forward for the rest of the drive, mastering himself, ignoring the landscape. She kept quiet. But something troubled her: hadn’t he said they stopped in Devon on that childhood holiday?

Griffin seemed to sniff the air. He found her again in the mirror. ‘Storm’s coming,’ he said, cheerfully.

The house, when they reached it, was not at all what Audrey had expected. The picture-postcard village, the sleepy scenery, the heavy afternoon with its feeling of sinking into a layer of dust, plus the fact that everyone kept calling it the big house: she’d prepared herself for a centuries-old confection of many wings and starched green lawns. Mellow bricks, a gravel drive; somewhere you could set a bonnet drama.