2,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

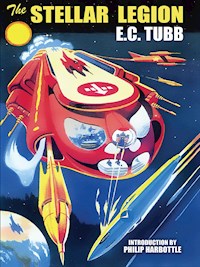

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Wilson, an unwanted waif of the generation-long war of unity, spends his boyhood in forced labour and persecution. Rebelling, he is sent as a convicted murderer to the newly colonised penal world of Stellar. He survives to win promotion in the Stellar Legion, the most brutal military system ever founded.

Laurance, Director of the Federation of Man, is afraid of the thing he has helped create, and tries to dissolve the Stellar Legion. He pits his wits against its commander, Hogarth, terrified lest the human wolves trained and hardened in blood and terror should range the defenceless galaxy…

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 210

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

THE STELLAR LEGION

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

THE STELLAR LEGION

E. C. TUBB

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 1954 by E. C. Tubb.

Reprinted with the permission of the Cosmos Literary Agency.

Published by Wildside Press LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

INTRODUCTION

by Philip Harbottle

The Stellar Legion was first published in the UK by Scion Ltd in 1954, and was one of Tubb’s best early novels. Notwithstanding, because of the unfair stigma applied to all science fiction novels issued by the minor British ‘mushroom’ publishers in the postwar decade, it remained out of print for some 45 years, before I was able to arrange for its reprinting by a US small press.

That the novel was overlooked for so long was particularly unfortunate because its militaristic background had anticipated many of the themes of Robert A. Heinlein’s widely known and acclaimed novel Starship Troopers, to which it was a fascinating precursor.

Heinlein’s book appeared in the USA five years after Tubb’s novel, and caused a storm of controversy, both pro and con. In England, British author Tubb would have a good reason to shake his head and smile wryly. Whilst his book was long out of print and almost forgotten, Heinlein’s novel went on to win the coveted Hugo Award for 1959.

Starship Troopers centred on the theme of the justification for a strong military force; in Heinlein’s novel, his soldiers save the human race by fighting against inimical aliens, the ‘Bugs’. Heinlein’s most assiduous critic, Alexei Panshin, referred to the book as ‘a militaristic polemic’ that shows ‘military life in the most glamorous terms possible’, giving ‘a direct philosophical justification for government veterans, and militarism as a way of life’.

E.C. Tubb was always a largely inspirational writer. That is to say, he was not someone who cold-bloodedly worked out his plot before he began writing. He required only to work out his basic opening setting and characters, and then inspiration took over, fuelled by Tubb’s especial forte: logic! Once he had created a basic situation, Tubb was able to extrapolate—logically—that such and such a situation was likely to occur, and then his novel took shape. The trick was to find that initial inspiration!

In 1999 Tubb told me that the initial spark of inspiration for The Stellar Legion came from his own reading of L. Ron Hubbard’s novel Final Blackout (1940,1948). Hubbard’s novel is well known, and has been either critically acclaimed as a militaristic masterpiece, or condemned as a fascist tract. It tells of how an army officer known as ‘The Lieutenant’ survives a devastating world war and its aftermath, to become the Dictator of England. What sparked Tubb’s imagination, he told me, was the idea of an individual who is born and raised in the midst of war, his whole being shaped by pain and terror. Assuming that such an individual could survive, how would he do it, and what would he become?

From this plot germ, Tubb developed the story of an orphan, Mike Wilson, whose early boyhood is spent in forced labour on Earth. Having been adjudged a murderer at the age of 17, he is sentenced to be deported across space, to a newly formed penal planet, Stellar. Here, he rises through the ranks of a ruthless military regime to become a sergeant in the Stellar Legion. (Like the noted American writer Wilson Tucker, Tubb was fond of using the real names of friends and acquaintances for his characters. ‘Mike Wilson’ was a friend and partner of Arthur C. Clarke, and a frequent visitor to the meetings of the London Circle of fans and authors. Trivia buffs might also like to note that ‘Mike Wilson’ was the name of the hero of Tubb’s 1961 strip cartoon war story, Hellfire Landing!)

Heinlein’s novel closely parallels much of Tubb’s story of Wilson in its account of his narrator, Rico, and his gruelling basic military training as a young man, followed by his graduation. But to some commentators, Heinlein’s award-winning novel fails to engage on the human level, being little more than a history of the making of a soldier, and a glorification of the military system. Tubb’s novel, on the other hand, is much more intriguing and darkly ambivalent. The rigours of Wilson’s military training are horrifying, and there is no glorification of war. Tubb’s prose—as ever—is lean and unsentimental, and Wilson’s actions are driven purely by a relentless logic, an exercise in personal survival.

What makes Tubb’s novel even more intriguing is how the story of Wilson becomes subsumed in the wider theme of the threat to peace to mankind (spread over several colonized solar systems and unified under a Federation of Man) posed by a highly trained and powerful military force. Tubb posits a military elite shaped by the motivation of personal survival dependent on obedience. But what would happen if a soldier from that elite were to be given a contra-survival order—when to obey that command could mean his own death?

With great panache, Tubb resolves his themes in a logical manner, culminating in a fascinating clash between his two other main characters. Laurance, the Director of the Federation of Man obsessed with the maintenance of a hard-won peace in the aftermath of interstellar war, versus Hogarth, fanatical military commander of the Stellar Legion. Tubb became engrossed with the writing of this novel, and told me that at the time it appeared, he was actually contemplating writing a sequel. In the new novel, Wilson became a lieutenant, and then…? Alas, not long after the novel appeared, its publishers, Scion Ltd., fell victim to the icy wind of change that blew across the UK publishing scene, and the sequel was never written. This is surely a matter of great regret.

In 1964, as a callow youth writing in my own fanzine, E.C. Tubb—An Evaluation, I said then of The Stellar Legion, that “it is worth noting the similarity between this novel and Heinlein’s much later Starship Troopers. Tubb wins hands down in every respect, in my opinion.”

Having just reread Tubb’s novel, I see no reason to change my youthful opinion! But you don’t just have to take my word for it—thanks to Wildside, you can now read Tubb’s lost classic for yourself!

CHAPTER 1

Fruits of Warfare

He was born in the midst of pain and terror, on a planet ripped and torn by war, and the arrogant throb of atomic destruction made a savage accompaniment to his baby wail. His mother never lived to suckle him, she, along with fifty million others died in the unleashed hell of the last missile raid on Earth and his father had vanished, a nameless memory, somewhere in the wastes of outer space.

Before he was a year old his skin had been seared by the agony of radiation burns, his food reduced to a nauseous mess, his comfort far less than that of the infinitely more valuable farm animals. He never knew love or affection, the gentle touch of a mother’s hand or the riotous fun of parental play.

He never had a toy, a nurse, a playmate or the understanding of an adult dedicated to his welfare.

They washed him, fed him, dressed his wounds, and then they left him, one of a hundred others, to live or die as nature saw fit. Soon he learned that crying only brought harsh words and rough hands so he ceased from crying and lay, hour after hour, day after day, month after month, staring with bright baby eyes at the low ceiling of the hospital, listening to the sobbing moans of men blasted beyond all semblance of human beings.

That he managed to heal his tormented body was a wonder. That he forced himself to walk, to see, to hang grimly onto his awareness was something never to be understood. That he lived at all was a miracle.

When he was eight they put him to work, toiling among the shattered ruins of cities, helping the broken remains of what had once been men to clear away the debris and build anew. The war had receded from Earth by then, the great ships of space were locked in conflict above the planets of alien suns, and other men and women, other children learned what it was to cringe helpless as atomic missiles drove in from the night of space.

When he was ten most of the independent worlds had fallen and now smarted beneath the rule of Earth, their fleets broken, their soil burned, their proud men and women accepting the inevitable and relinquishing their dream of self-rule. They grumbled, glowered, then, as reason returned and the ghastly price of liberty cried in pain-filled voices around them, swallowed their pride and set to work to build the Federation of Man.

When he was twelve they took him from the cities and set him to work at reclaiming the poisoned soil. He had a name by now, and a number, and of the two the number was the most important.

He worked from dawn to dusk, shovelling the radiation-tainted dirt into great hoppers where it was neutralised, enriched with humus and fertilisers, and replaced ready for the planting. It was hard work, thankless work, and dangerous. The radiations, even though nullified by the passage of time, still retained enough force to inflict ugly burns, and he sweltered in heavy protective clothing as he worked on the edge of the blue-limned desert that had once been Kent.

He had an overseer, a tough, scarred veteran of space, a man embittered by his own incompetence and in perpetual pain from his badly fitted artificial legs. A short, stocky man, addicted to crudely distilled spirits and with a sadistic streak to bely his outer manner. A man, who for some obscure reason, hated the thin, grey-eyed, dark-haired boy with the blue scar of an old wound marring the side of his neck and blotching his cheek.

“Hey, you,” he yelled. “Wilson.”

“Yes?” Wilson stood, fighting the sudden knotting of his stomach muscles, the thick hood of his protective clothing thrown back from his pale, blue-scarred features. The overseer snarled and walked painfully forward.

“How many times do I have to tell you, you swine? When you speak to me you call me ‘sir’. Get it?”

“Yes, sir.”

“That’s better. Now grab some food and get back to work. We’re behind schedule and the inspectors will be coming to examine progress in a week or two. I want to show them that we can do our share.”

Wilson hesitated. “I’m due for a rest period, sir.”

“Are you arguing with me?” Anger convulsed the overseer’s heavy features and his right hand clenched into a club of bone and sinew. “You heard what I said. Eat and get back to work.” He glowered at the other nine boys making up the work party.

“That goes for you, too. All of you. I’ve had my eye on this group, idling and wasting time when you thought that no one could see you. Well, now you’re going to pay for it, and you’ll work double shifts until I tell you to stop.”

Silence fell over the little group and one of the boys, a delicate-faced youngster with a twisted leg and a hunched back, began to cry. The sound seemed to touch off a devil in the stocky man’s heart and he swung, his muddy eyes glinting as he stared at the clustered youths.

“Who’s whining?”

They shuffled, trying not to meet his eyes, and yet trying not to betray their comrade.

“I said, who’s whining?” The overseer smiled, a savage twisting, of his lips utterly devoid of humour, and something animal-like and sub-human shone redly in his eyes. “So it’s you, Carter, I might have guessed it.” He jerked forward and grabbed the sobbing boy by the arm. “What’s the matter, son?” he purred. “Did your mummy forget to tuck you in last night? Did your daddy forget to kiss you?” He laughed and, sycophantically, a few of the boys laughed with him.

They didn’t mean to be deliberately cruel, but to them the concept of ‘father’ and ‘mother’ was utterly foreign. Most of them had been alone ever since they could remember and, unlike the sobbing boy who had only been orphaned a few months, to them the crude jest seemed meaningless.

“How old are you, son?” Still the mockery purred in the thick voice and Carter wiped his eyes as he stared up at the big man.

“Thirteen, sir.”

“Almost a man aren’t you? In a year or so you’ll be inducted into the army, or you would have been if it hadn’t been for that twisted spine of yours.”

The big hand tightened on the frail arm. “You’re not strong enough to work on the deadlands, son. You’d better come with me, I need a batman and I can use you. The last one died on me, fell over in the dark and broke his neck.” The purr in the thick voice deepened. “You want to serve me, don’t you?”

“I don’t know, sir. I…”

“Do you want to work yourself to death, boy? Do you want to go as these others are going? You know what happens out there, you know how the radiations burn and blind, sear and distort. Be my batman, son, and you’ll miss all that. Well?”

Carter licked his lips with a nervous gesture and stared appealingly at the blank faces around him.

He was a stranger, someone fresh from a life none of them had ever known, and they had long since learned the lesson of minding their own business.

They avoided his eyes.

“Yes, sir,” he said helplessly. “I’ll be your batman.”

“Good.” The overseer grinned and thrust the youth towards a huddle of low buildings. “Go and clear out my hut, you know where it is, and make a good job of it.” He turned to the others. “Now you fatherless scum, get back to work, and work hard. If you don’t…” He lifted his big fist and spat on the dirt at his feet. “I’ll make you wish that you’d never been born.”

He turned, walking with his jerking awkward stride towards the huddle of buildings, and silently the boys watched him go.

“The swine,” said Wilson emotionlessly. “The dirty stinking swine!”

“Yeah.” One of the others twisted his lips in contemptuous disgust. “I’ll be glad to get the hell out of here. Nothing could be worse than this, not even the attack forces.” He stared enviously at the blue-scarred boy. “You’re lucky. Another year or so and you’ll be old enough for the Fleet, they’re taking them in at fourteen now I’m told.”

“Maybe.” Wilson shrugged and turned towards the mess hut. “The war may be over by then.”

“It won’t be,” said the boy with quiet conviction, and shuddered as screams echoed thinly from the huddle of buildings. “The damn thing’ll go on forever.”

He was wrong.

Peace was declared two years later, signed and ratified over the smouldering ruins of the last desperate battle, and the Federation of Man was a cold fact. It had taken twenty years of constant struggle to weld the scattered colonies into a homogeneous whole, to break forever the stubborn pride of local groups and to end the inevitable threat of warring empires and divergent cultures. Now, after a generation, it had been accomplished, and the Federation of Man, born in hate and fear, in struggle and death, ruled the known stars.

There were splinter groups, of course, isolated planets with a single city and perhaps a few space ships, but they didn’t count. What did count was the fact that the independent colonies now recognised the Mother Planet and acknowledged Earth as their nominal ruler, and, for the first time in a generation, men breathed the sweet air of freedom and the huge inter stellar ships traded once more between the stars.

Three years later, when Wilson was seventeen, the war was a thing of the past. Men streamed home and took up the reins of a disturbed existence, satisfied to farm and till, to work and build, their past forgotten, the ethics of the war, ignored, the long-term policy submerged in day to day interests.

Machines, turned from war-potential, cleared away the rubble and turned the revitalised soil. Cities reared towards the stars and the great warships lost their guns and atomic missiles, were ripped and altered, turned into harmless cargo vessels and passenger ships, sent to the outposts of the new Federation and once again all men were brothers.

Almost.

For still the unwanted remained, the children of war, the parentless, the waifs, the orphaned young and the footloose adventurers. They knew nothing these people, nothing but toil and the trade of death and in a peaceful world they were unwanted, unnecessary, and dangerous. So they were forgotten, ignored, their existence denied, shelved as an unfortunate problem which time would solve, and the new-born Federation unified itself and turned from war to peace with an energy born in dreams and a generation-long reaction from enforced discipline and conscription.

With peace came a revulsion of all things appertaining to war. The Terran fleet melted as its personnel dispersed, and men regained their personal liberty in a derision of all things military, so that a man in uniform became a thing of amused contempt, and the stiff discipline of armies a hateful burden.

Peace came.

CHAPTER 2

An Admiral Speaks

Three men sat in a luxurious room at the summit of the highest building in rebuilt London.

From high windows the dying light of the setting sun threw long streamers of red and gold, orange and pink, yellow and soft amber across the polished surface of a paper-littered table, reflecting in warm hues from the panelled walls. As the light died selenium controls clicked and subdued fluorescents restored the illumination.

Admiral Hogarth sighed and picked up a thin sheaf of papers from the pile before him. A tall man, his back die-straight and his thin shoulders square to his slender body, he fitted his neat uniform as though born to the black and gold.

Sparse white hair swept back from a high forehead and his eyes, pale, washed out blue, glittered from either side of a high-bridged, hooked nose beneath which his thin lips made a tight gash.

“It is decided then?” His voice was harsh, cold, emotionless and with the whip of ingrained command. “It is final?”

“It is.” President Marrow looked at the third man. “Both Director Laurance and myself agree with the findings of the Committee and they are final. The Terran fleet is to be dispersed, the ships converted to commerce and the men and officers to have free choice either of continuing to operate the ships as civilian crews, or to be landed, free from military service, on any planet they may choose.”

“You agree with this?” Hogarth stared at the fat Director and Laurance shrugged.

“Naturally.”

“I see.” The tall Admiral thinned his gash of a mouth. “And what are your plans concerning myself?”

“That,” said the President quietly, “is the sole reason for this conference.” He leaned back in his chair, an old man, tired, with the marks of ceaseless worry graven deep into his seemed features and his hairless scalp glistening in the soft lighting. “You present a problem, Hogarth, and I’m not attempting to deny it. For twenty years now you have had almost supreme power, in a way Earth owes you everything, for it was your fleet which smashed the Independents and established the Federation of Man, but that is over now, and frankly, we cannot afford nor tolerate a large military force.”

“So you plan to leave yourselves defenceless?”

“Against what?” The President smiled and gently shook his head. “I understand you, Hogarth, please believe that, but you must accept the inevitable. Your fleet now has no further reason for existence, and with its passing…”

“I am an embarrassment.” Hogarth nodded, his head dipping in a stiff, almost imperceptible salute. “I understand.”

“I am glad that you do,” murmured the President, and Laurance chuckled as he mopped his broad face with a square of gaily coloured linen.

“We’ll find you a job, Admiral,” he said cheerfully. “We don’t know just what it will be yet, but there’ll be something, you needn’t worry.”

“I’m not worried,” said Hogarth tightly, “but you should be. What you propose is madness, sheer insanity, the abject logic of cowardice. You think that because the war is over you no longer have need of the space fleet. You are wrong. What of the insurgent worlds? What of the Raiders? What of the constant threat of rebellion?”

“Please.” The President lifted one thin hand in a silent gesture. “Don’t think us fools. We shall continue to operate a small armed force but it will be a local responsibility, a special police patrol more than anything else. We are talking now of the Terran Fleet, the mighty war engine you built and to operate which took the total resources of three worlds. That is finished, and, even if we wanted to keep it functioning, we couldn’t do it.”

“Why not?” Hogarth shrugged. “Because of the supply worlds?”

“No,” said the old President gently, “because of the men.”

“Nonsense!” For the first time the tall Admiral displayed emotion. “My men are loyal, they would fight and serve to the death, and…”

“Your men are deserting,” interrupted Laurance impatiently. “While they were at war they would fight as you said, but not now, not now we are at peace and it’s time to grow up.”

“How dare you!”

“He’s right, Hogarth,” said the President wearily.

He sighed as he looked at the rigid figure of the Admiral, half-dreading what must be said and yet knowing that there was no alternative. A gigantic military machine had no place in the new Federation and both it and the men who ran it had to go. To retain it would be to strain the resources of too many worlds, occupy the valuable time of too many men, and always there would be the temptation of some highly placed officer to desert, to take a few ships, raid a planet for women and supplies, and head out into the depths of space, to the untouched stars waiting beyond the frontiers of the known worlds, and there establish a private empire.

It had happened before, half the Independent planets had been founded by exploiters and would-be dictators, and it had taken twenty years of savage fighting to break their local groups and to assimilate them into a homogeneous whole. It must not happen again.

Laurance was speaking, using the glib phrases of the born diplomat, and the old man listened to the honeyed words, knowing them for what they were, and yet hoping that the Admiral would take them at their face value. He hoped that Hogarth would, for the man still had power, still had control of a section of the Terran Fleet, and if he wanted to be awkward…

Apparently he didn’t.

“I can follow your logic,” he said stiffly, “but that doesn’t mean I agree with it. Personally, I think that you are making a mistake, but you have the power, and you have the rule.”

The old President frowned, half-catching the hint of mockery in the cold tones, but before he could speak Laurance had plunged ahead.

“…so you see, Hogarth there is nothing else we can do. The work of restoration simply does not permit of the drain necessitated by a large armed force, and it must be absorbed into the overall pattern. In fact we have already altered more than half the vessels and released most of the men and officers. All that remains now is to find you suitable employment, or if you would prefer retirement...”

He let his voice fade into a hopeful silence and for a moment the two men waited for the tall Admiral’s reply.

“I do not wish to retire,” he said coldly, and the fat man sighed in open disappointment.

“Then…”

“Before you decide,” said Hogarth sharply, “May I speak?”

“Certainly.”

“Thank you.” This time there was no mistaking the irony in the tall man’s cold voice. “I will not waste your time on further arguments on retaining the fleet, but there is a point which you seemed to have overlooked.”

“Yes?” Laurance was still polite but his expression showed that he was getting fed up with all this and was eager to return to more constructive employment than persuading an unwanted Admiral that his time had passed.

“There is still need of a fighting force.” Hogarth frowned at the fat man’s instinctive gesture of annoyance. “Not, if you insist, from human enemies, but we have not explored the entire universe and it would be presumptuous for us to imagine that of all the worlds in the galaxy only our own has spawned life.”

“We have found no other,” said the President gently. He was an old man and could appreciate the other’s battle to retain a shred of dignity and power.