9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

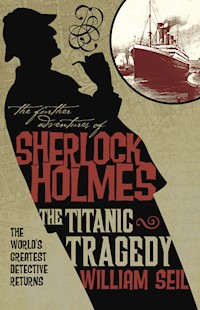

Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson board the Titanic in 1912, where Holmes is to carry out a secret government mission. Soon after departure, highly important submarine plans for the US navy are stolen. Holmes and Watson work through a list of suspects which includes Colonel James Moriarty, brother to the late Professor Moriarty - will they find the culprit before tragedy strikes?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

AVAILABLE NOW FROM TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES SERIES:

THE ECTOPLASMIC MAN

Daniel Stashower

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

Manley Wade Wellman & Wade Wellman

THE SCROLL OF THE DEAD

David Stuart Davies

THE STALWART COMPANIONS

H. Paul Jeffers

THE VEILED DETECTIVE

David Stuart Davies

THE MAN FROM HELL

Barrie Roberts

SÉANCE FOR A VAMPIRE

Fred Saberhagen

THE SEVENTH BULLET

Daniel D. Victor

THE WHITECHAPEL HORRORS

Edward B. Hanna

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HOLMES

Loren D. Estleman

THE GIANT RAT OF SUMATRA

Richard L. Boyer

THE ANGEL OF THE OPERA

Sam Siciliano

THE PEERLESS PEER

Philip José Farmer

THE STAR OF INDIA

Carole Buggé

THE WEB WEAVER

Sam Siciliano

the

further

adventures of

SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE TITANIC TRAGEDY

WILLIAM SEIL

TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE TITANIC TRAGEDY

Print edition ISBN: 9780857687104

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857687128

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First edition: March 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for dramatic purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 1996, 2012 William Seil

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to Reader Feedback at the above address. To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed in the USA.

This book is dedicated to my mother

Marguerite Seil

and the memory of my father

Emery Seil

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Acknowledgements

Chapter One

THE EVENING OF TUESDAY 9 APRIL 1912

In the spring of 1912, at the age of sixty, I was leading a solitary life in rooms in Piccadilly. While continuing to see a few regular patients, I had, for the most part, ended my medical practice. My working time was now devoted almost entirely to writing historical novels. This turn in my writing career had come as quite a surprise — and I must say, disappointment — to my publisher, who would have preferred that I did nothing but record past adventures of my friend, Mr Sherlock Holmes. As a favour to him, and many loyal readers, I occasionally sifted through old notes on Holmes’s cases and produced a new manuscript. But I also was respectful of Holmes’s desire for solitude and anonymity.

Holmes had long since retired from his illustrious career as a detective and was now living on a smallholding on the South Downs. He rarely came to the city, but several times a year I would travel to his country retreat and inform him of whatever news I had heard about recent criminal investigations. I often called at Scotland Yard to see young Inspector Wiggins, who provided me with detailed accounts of current cases. There were times too when Wiggins, baffled by a particularly complex case, would travel to Sussex to consult his old mentor.

My visits to Holmes seldom involved talking over old times. He had little patience with nostalgia. Whenever my conversation wandered to decades-old memories of past cases, he would rise from his chair and draw me over to one of the many scientific projects that were in progress in and around his home. I was always reluctant to visit the beehives he kept in his orchard, even when I was fully covered by protective clothing. But I was fascinated by his promising work in the scientific analysis of crime evidence. I recall one day in particular when we travelled to a local inn to purchase drinking mugs — that is, unwashed drinking mugs, taken right off the bar. After giving the landlord a generous payment, Holmes gathered up the mugs with a gloved hand and packed them into a box. At home, he applied various dry chemical mixtures to the glass, hoping to develop a method of bringing out detail in smudged fingerprints.

I thought about Holmes as I sat at my dining room table late one night, researching the early battles of the Boer War. Outside, the wind howled and heavy rains rattled against the windows. I had just put another log on the fire, and it was engulfed in crackling flames. I welcomed these sounds. My rooms had been much too quiet since the death of my wife six months earlier. I thought back to other stormy nights at Baker Street, when there would be a knock on the door, and a rain-soaked stranger, speaking to us in frightened, confused or demanding tones, would ask our help in solving a problem. But those days were gone, like all the history that lined my bookshelves.

As my mind wandered, I decided that it was time to abandon my research for the evening. Leaving my books on the table, I walked to the window and looked at the street below. In the glow of the street lamps, I watched as the rain poured on to the cobbled street and rushed along the gutters. Except for the fury of Mother Nature, the streets were quiet. The only sign of life was a small pack of neighbourhood dogs conducting their nightly prowl of the area. I was about to leave the window and retire to my bedroom when I noticed the flash of headlamps approaching up the street. A large, black motorcar came to a stop directly in front of my rooms. The headlamps blinked off and, for several minutes, it appeared that no one was going to leave the car. But then a man stepped out of the driver’s seat and rushed to the back to open the door for a passenger. The man in the back seat, wearing a dark hat and raincoat, climbed out of the car and immediately looked up to the window where I was standing. We watched each other for a few moments, before he lowered his head and walked in the direction of my door.

I heard his knock, just as I reached the foot of the stairs. I tightened the collar of my dressing gown round my neck, slid back the bolt and opened the door. The gust of cold, wet wind penetrated my body, and I began to shiver. But the stranger stood calmly, as though this were a casual visit on a sunny afternoon.

‘Doctor Watson?’

‘Yes.’

‘My name is Sidney Reilly. May I come in?’

‘It’s very late. Unless this is a medical emergency, I must ask you to come back in the morning.’

‘Doctor,’ he said with a half-smile. ‘I have an important message for you from Mr Sherlock Holmes. And by tomorrow morning, I suspect you’ll be on a ship bound for America.’

I froze for a moment, not knowing whether I should believe this extraordinary statement. But then, the appearance of this stranger at night was worthy of Holmes’s sense of drama. Ten years earlier in Baker Street, I would not have been so fearful of admitting a mysterious late-night caller. But then, ten years ago I would probably have remembered to slip my service revolver into my dressing gown before opening the door.

I pulled the door back and asked Reilly to follow me upstairs. As we entered the drawing room, I took his rain-soaked hat and coat. Reilly was a dark, trim man in his late thirties. When he spoke he had a trace of an accent, or mixture of accents. He had calm, piercing eyes that seemed to gaze over every feature of the room as he walked towards the fire.

‘Doctor, I have been told that you are aware of the high position Mr Holmes’s brother, Mycroft, holds in our intelligence service. I too work for the government, and when Mycroft Holmes picks you up in the morning to take you to the railway station, he will verify that. He would have accompanied me this evening, only he had to make some last-minute arrangements for his brother.’

‘Forgive me if I am sceptical, Mr Reilly. But let us assume for the moment that what you are saying is true. Why would you expect me to be boarding a ship for America in the morning? Is this something Holmes wishes me to do?’

Reilly reached into his pocket and handed me a small envelope. It was addressed to me in Holmes’s handwriting. ‘I haven’t read it, but I believe that note will answer at least some of your questions,’ he said.

I tore open the envelope and read the note, which had been dated that same day:

My dear Watson,

I realize that this request comes at a particularly sad time for you, but once again, I am in need of your help. In the morning I will board a ship for America, and will not be seeing you again for some time. The government has asked me to conduct a secret investigation and, after some encouragement from persistent senior officials, I have accepted. I would appreciate it if you could find your way clear to join me on this voyage. My investigation does not begin until I reach America, so the voyage will be relaxing and uneventful. The trip would do you good and I would greatly enjoy seeing you at the start of this adventure. However, after we reach New York, I fear that my mission will lead to our separation, so come at once if convenient—if inconvenient, come all the same. Mr Reilly will provide you with a ticket.

Very sincerely yours,

Sherlock Holmes.

‘I am convinced, Mr Reilly. I will have my cases packed and be ready to travel in the morning.’

‘Very good, Doctor. That concludes our business. You understand, of course, that everything you see and hear — including our meeting tonight — must be treated in the strictest of confidence. Your friend, Mr Holmes, is undertaking a mission that could prove to be a turning point in the nation’s security.’

‘During my long association with Holmes and his clients, I have never betrayed a confidence. You can rely on me, completely. Now, can you tell me with what I am getting involved?’

‘I regret that I am unable to oblige. Mr Holmes will tell you as much as he can, once you get on board the ship. But I can tell you that your friend is a hard man to bring out of retirement. I’m sure you’re familiar with Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty. Well, he and I first visited Holmes’s retreat about a week ago to ask for his help. He listened to us, but wasted no time in turning us down. It was only after we made a return visit with the Prime Minister and Foreign Minister that he agreed to carry out the investigation.’

I chuckled. Retirement had done little to change Holmes. He remained as independent as ever. Even as Holmes approached his sixties, he could not resist a challenge to his remarkable talents.

Reilly began strolling around the room, first examining the mantelpiece, then the bookshelves. After perusing everything with a quick sweep of his eyes, he turned to me with a look of disappointment.

‘Forgive me, Doctor,’ he said. ‘I’ve read every article you’ve written about your adventures with Mr Holmes. I was expecting to see a few keepsakes from 221B Baker Street... Maybe some of Holmes’s scrapbooks, or a Persian slipper full of tobacco hanging from the fireplace. But there’s nothing here, and I saw very few mementoes at Mr Holmes’s country estate. If you will forgive my curiosity, what happened to it all?’

I took Reilly by surprise with a hearty laugh. ‘Do you believe in time travel, Mr Reilly?’ I motioned to a closed door next to the sideboard. ‘If you’ll step through that doorway with me, I will take you on a journey into the past that would make H G Wells envious.’

I struck a match on the mantelpiece and opened the door. Light from the electric lamp over my dining table stretched across the fading twenty-year-old carpet in the adjoining room. ‘This is the one room in the house where I don’t allow electric lights.’ The first match had burned to my fingertips, so I struck a second one and lit two oil lamps that were fixed to the walls.

‘Mr Reilly, welcome to 221B Baker Street. If you look around, I’m sure that you’ll find more than enough mementoes to satisfy your curiosity.’

Until now Reilly had been emotionless to a fault. But suddenly, upon seeing this room, his eyes lit up and he began a whirlwind examination of its furnishings. ‘This is wonderful, Doctor. I can’t believe it. It’s just as you described your Baker Street rooms in the articles.’

‘Well, I confess that I never expected to become a museum curator; nor that my past life would end up as an historical display. But when Holmes moved out of 221B, I just couldn’t accept seeing all those memories of happier times being scattered about. So Holmes generously gave everything to me, and bought new furnishings for his country home. Of course, there were a few pieces that he could not part with. For example, if you’ll look over at that side table next to the settee, you’ll see a violin. I had to purchase that at a second-hand shop. Holmes took his with him. But most of the furnishings are original.’

‘Back there, in the corner, is that where Holmes conducted his experiments?’

‘Yes, smelly old things they were, too. I used to welcome the aroma of Holmes’s tobacco smoke, because it would cover up the smell of sulphur. Here, let me give you a tour.’

Reilly sat in Holmes’s velvet armchair and, after asking permission, tried on the deerstalker cap that was hanging on the wall rack. He chuckled at the stack of letters that were fixed to the mantel with a jack-knife.

‘Tell me, Doctor. The letters VR that are perforated in the wall. Did you reproduce them with a revolver, as Holmes did, or did you use a quieter, more conventional approach?’

‘I used a hammer and a spike. I am not as precise a marks-man as Holmes, and the London police these days are less tolerant of the sound of gunshots than they used to be.’

‘Mr Holmes was a remarkable man.’

‘He still is. Just a little less active.’

Reilly froze for a moment, his eyes fixed on the floor. When he looked at me again, the cold, commanding gaze had returned to his eyes.

‘Doctor, I am concerned about the safety of your friend, and the success of his mission. It is important that when you see Mr Holmes on the ship, you bring certain facts to his attention.’

‘And what might those facts be, Mr Reilly?’

‘Simply, Doctor, that times have changed. And so has the world in which Mr Holmes will be carrying out his mission. Mr Holmes has confronted opponents who were both cunning and dangerous. Still, most of them had certain standards by which they played the game. I don’t quite know how to define it. You might call it a Victorian ethic...something in their upbringing that tempered their lawlessness. Doctor, believe me when I tell you, that that is not the case in modern espionage. Mr Holmes will be dealing with individuals who care nothing about human life. He will be in grave danger. And unless he is willing to become as cold and ruthless as his opponents, I suspect he will not survive.’

I did not know how to react to this extraordinary statement. At first, I was offended that this upstart should be so disrespectful of Holmes’s experience and abilities. Still, there was something in his manner that told me that he knew his business, and he did not give idle warnings.

‘Mr Reilly, I assure you that Mr Holmes is quite capable of taking care of himself. He may not be as young as he used to be, but his mind is as sharp as ever. And as for cunning opponents, if you’ve read my articles, you must be aware of his confrontation with the late Professor Moriarty. As you may recall, Holmes had laid a trap from which the professor knew he and his cohorts could not escape. When Holmes refused to back away, Moriarty on several occasions sent henchmen to kill him. Holmes and Moriarty had their final confrontation at Reichenbach Falls, where they struggled and Moriarty fell to his death. I could scarcely imagine a villain as dangerous as the professor.’

‘As I recall, Doctor, at Reichenbach Falls — before the struggle — didn’t Professor Moriarty allow Mr Holmes a few moments to write a note to you, explaining what was about to take place? I seem to recall from your work that you found such a note under Holmes’s cigarette case when you returned to the Falls.’

‘Yes, the professor waited whilst Holmes wrote a brief note. It was a simple courtesy and posed no added danger to the professor.’

‘My point, Doctor, is that a professional agent would not have confronted Holmes face-to-face—let alone allow him the time to write a note. He would have killed Holmes quietly, at the first sign of trouble, with a knife in the back or a garrotte around the throat. That’s the type of opponent Holmes will be facing. I’m alive and speaking to you today, only because I have been willing to play as rough as my opponents.’

‘I remain as confident as ever in Holmes’s abilities,’ I said quietly. ‘But I will do as you say and pass on that word of warning.’

‘I hope so, Doctor. I hope so. I am a great admirer of Mr Holmes. I would hate to live with the memory that I had sent him on his final adventure.’

I handed Reilly his hat and coat as he stood at the top of the stairs, preparing to step back out into the pouring rain. Before buttoning his coat, he reached into an inside pocket and pulled out an envelope. ‘Thank you again for the journey back in time, Doctor. Here’s your ticket for tomorrow. I hope you enjoy the voyage, and please remember what I said.’

‘I will, and thank you again, Mr Reilly.’

I walked down the stairs with Reilly and opened the front door for him. He stepped out to his motorcar, as the driver opened the door to the back seat.

After bolting the front door, I walked back upstairs and warmed myself by the fireplace. I took a clean butter-knife from the sideboard and opened the envelope Reilly had given me. I was pleased to see that it contained a first-class ticket, since I had long made a habit of treating myself to comfortable travel accommodation. Not only that, but the ship itself would make this a rare treat. I would be travelling on the maiden voyage of the biggest, most luxurious ship ever built. Its name was written on my ticket in proud, bold letters — RMS Titanic.

Chapter Two

THE MORNING OF WEDNESDAY 10 APRIL 1912

Mycroft’s motorcar pulled up at Waterloo Station well in advance of the Titanic Special Service’s departure at a quarter to ten. I had packed a large suitcase in haste for the journey, hoping to purchase whatever else I might need on board the ship, or in New York. Mycroft was trimmer and more energetic than he had been when I last saw him, some three months earlier. It appeared that my lectures on his poor dietary and exercise habits had had their desired effect. He confided to me that members of the Diogenes Club, who had known him for decades, were astonished to find him taking morning walks.

‘Have a good time, Watson,’ said Mycroft, as we stood by the kerb, waiting for the driver to give my bag to the porter. ‘And please suggest to my brother that he might find a holiday beneficial.’

A newspaper photographer stepped out of the crowd and pointed his camera in our direction. Mycroft immediately moved towards his car, turning his back on the enterprising photographer who, after a few moments, gave up and went in search of a less bashful subject.

‘The departure of the Titanic appears to be quite a significant event,’ Mycroft said. ‘That’s understandable, of course. When it was launched last year, more than 100,000 people came to watch. I had the opportunity to go on board for a short time during its sea trials. It is a beautiful ship — the biggest there is. Inside, it is like a city, carrying up to 3,300 passengers and crew, with every diversion for a sea voyage that one could wish for — squash courts, a swimming pool and even lifts to carry you from deck to deck.’

‘I would expect to see Fleet Street represented at the departure of the ship itself, but why here at the boat train?’

‘A fascination with the rich and famous, I suppose. This Special carries only first-class passengers. Second and third class took another train a couple of hours ago. You will be meeting a few celebrities, I have no doubt.’

‘At the moment, I’m more interested in how I will locate Holmes on board that huge ship. Do you know his cabin number?’

‘It is close to your own and he will find you. He has a talent for that kind of thing, you know. And remember, he’ll be travelling under an assumed name. It would not be wise to tell others he is on board. Only you and the captain will be aware of his presence — and, of course, Miss Christine Norton.’

‘Perhaps I’m getting a little confused in my old age, Mycroft. But why tell the captain that Sherlock Holmes is among the passengers? And who is Miss Norton?’

‘Oh, have I not mentioned Miss Norton? She is a courier for the Ministry. Very young, but intelligent and resourceful. Her mission is to take some secret military papers to the United States and I have asked Sherlock to look after her. The captain has been alerted that the three of you are on a secret mission and was asked to provide you with any assistance you may require.’

I am and always have been an even-tempered man. But I do not like being deceived, especially by a friend. I paused for a moment to contain my anger, then replied to Mycroft’s extraordinary statement in calm, but firm tones.

‘Do you mean to say that I have been roped into some kind of spy mission? I understood that I was to go on a quiet ocean voyage with an old friend. Now, it appears, I’m in the middle of some sort of intrigue.’

‘You do indeed appear to have changed, Watson. I remember you as a man with a sense of adventure.’

Mycroft’s face broke into a broad smile, one that caused me to become even more annoyed by his deception. But I began to wonder at that point whether I had over-reacted. After all, the train was still at the station. There was still time to back out.

‘It is merely an exchange of documents. I will admit, the papers in question are of a highly delicate nature. It would be critical if certain foreign powers obtained them. But no one knows they are on board. You might like to remind yourselves of them now and then in between games of squash and shuffle-board.’

‘I will take your word for it, Mycroft. But I would have appreciated an earlier indication of the true nature of my task. Now, how will I recognize this lady of the name of Miss Norton?’

‘You do not know her. But I believe you have met her mother.’

‘You don’t mean...! Is Holmes aware that he will be working with Mrs Irene Norton’s daughter?’

‘Not yet. For security reasons, he has not been told the lady’s name; only that she will contact him in his cabin. You might like to tell him the rest after the ship departs. It should be a pleasant surprise for him. I don’t believe that he has ever met the young woman.’

‘Mycroft, I do believe you are becoming as deceitful as Professor Moriarty himself. But I do thank you for this opportunity to see Holmes before he begins his mission in the United States. Your Mr Reilly tells me there is some danger.’

Mycroft started, then peered into the distance as if lost in thought.

‘It is a dangerous world, Watson. A very dangerous world. But my brother has encountered danger many times in the past. I am confident that he’ll make it through this ordeal. Meanwhile, you have a train to catch. I will not detain you any longer. Tell Sherlock that I will dine with him at the Diogenes Club when he returns.’

We shook hands and I walked quickly into the station, which had a clean, modern look, following its recent renovation. The boat train was not difficult to locate. It was the centre of attention, surrounded by well-dressed passengers, with their friends and relatives who were seeing them off. Porters and servants were moving quickly to load the train. I hurried to my compartment in one of the chocolate-brown coaches.

It was a relaxing eighty-mile journey, passing through Surbiton, Woking, Basingstoke, Winchester and Eastleigh, on its way to the White Star berth at Southampton docks. Shortly after the train left Winchester, I decided to walk down to the dining car for some tea and biscuits. There was little of interest in the morning paper and, growing tired of my private compartment, I was in the mood for some conversation with other passengers — perhaps some of the ‘rich and famous’ Mycroft had mentioned. But as I entered the dining car, I found that all of the tables were occupied. This turned out to be a blessing, in disguise. An uncommonly attractive young woman — perhaps thirty years old — was sitting alone. I approached her and asked if I might join her. She readily acquiesced.

‘Thank you. I was afraid, for a moment, that I would have to order tea in my compartment. This is much more pleasant. My name is Watson, Doctor John Watson.’

She stared at me for a moment and then asked tentatively, ‘Might I inquire if you are the Doctor Watson who wrote about Sherlock Holmes?’

I confessed that I was.

‘This is indeed fortuitous. I read one of your adventures in an old Strand Magazine only a few weeks ago. My name is Miss Holly Storm-Fleming.’

There was something about the lady’s appearance and manner that was almost contradictory. This was clearly a lady of taste and breeding. She wore a silken, light blue dress with white lace trimming. When she spoke, her voice was clear and expressive, with a slight American accent. Her light brown hair was perfectly in place, falling softly about her shoulders. Yet, she was not at all reserved. Miss Storm-Fleming possessed an unrestrained vitality that brightened her every word and move.

‘It is my pleasure, Miss Storm-Fleming — or should I say Mrs?’

‘My husband passed away two years ago. Fortunately, his estate was large enough to enable me to live comfortably and go back to the United States whenever I like...’

‘Are you from America?’

‘Yes, I was born and raised in Chicago. I moved to New York when I was twenty-one. That is where I met my husband, Gerald. He was there as part of a British trade delegation, and I had a small part in a Broadway production. The members of the delegation attended one of our performances and afterwards they were invited to a reception to meet the cast. We started talking and, the first thing I knew, I was heading back to London with him.’

‘And now you’re returning to New York. Do you go there to visit friends, or is this just an opportunity to travel on the Titanic?’

‘Oh, a little of both, I suppose. I still have good friends in the theatre, and I will be getting together with them. But on this occasion, I have to confess, the Titanic was a big part of it. And how about you, Doctor? Why are you taking this voyage?’

‘I find that I am getting on in years and I discovered that — although I’ve travelled extensively on several continents — I have never been to America. This seemed like an excellent opportunity.’

‘Will Mr Holmes be on board? I’d love to meet him.’

I was not in the habit of lying. I especially did not want to be dishonest with someone as kind and charming as Miss Storm-Fleming. But national security and Holmes’s own safety were at stake. It was indeed important that I was discreet.

‘Unfortunately Holmes will not be travelling with us. He is retired now, but still very involved in several research projects. I am afraid he has little interest in being idle on board a ship.’

The remainder of the journey passed by quickly. It was not long before the train arrived at Southampton and we were approaching the docks. We arrived at half past eleven, precisely on time. The boat train wound its way along the water-front before slowly turning on to a side track flanking the White Star dock at Berth 44.

Miss Storm-Fleming and I parted company in the dining car, so that we could return to our respective compartments to gather up our belongings.

‘I look forward to meeting you again on board ship, Miss Storm-Fleming. Allow me to ask you to join me for dinner one evening.’

‘I will be looking forward to it, Doctor... Imagine, meeting the famous Doctor Watson. This voyage will be more exciting than I expected.’

Chapter Three

NOON ON WEDNESDAY 10 APRIL 1912

The Titanic was indeed a magnificent sight. It was, of course, a huge ship. But beyond its size, it had a grace and stature reminiscent of the stately wooden sailing vessels that had excited me so in my youth. But with modern engineering, crossing the Atlantic was no longer a hardship. It was more like spending a week in a fine hotel.

The ship’s superstructure shone in the midday sun. The thin gold line at the hull’s upper edge clearly and proudly identified the new vessel as part of the White Star Line. The Titanic’s four huge funnels towered against the blue sky. The air was crisp, and there was a smell of burning coal in the air. As I moved with the crowd, the excitement of the approaching journey began to affect me.

Before stepping onto the gangway, I moved to the side and examined my ticket. My cabin was on C Deck, on the port side. I was eager to see the Titanic’s accommodation. The advertisements I had read had promised unparalleled luxury.

When I reached the deck, one of the stewards also examined my ticket and led me across the wooden decks through a doorway to the interior of the ship. The steward, an efficient young man with little time to spare, marched quickly through the corridors until we came to the door marked C28.

I was most favourably impressed by my quarters. They were small, but much more homelike than other ships’ cabins I had seen. There was a large green sofa, a wardrobe and a dressing table. I was especially pleased to see the comfortable-looking bed, rather than a fixed berth.

‘The gent’s lavatory is down the hall and to the right,’ said the steward, pointing aft of the ship.

‘I understood that there were private baths on this deck.’

‘There are, sir. One cabin in three has one. The cabins are arranged in groups of three that can be let together, or separately. There are connecting doors, but do not be concerned. They are all locked here in this section.’

‘And since my cabin opens to the main corridor, I won’t have a view of the water. I was hoping to have a window.’

‘Oh no, sir. All first-class cabins have a view. Over there in the corner there’s a little passage to your porthole.’

‘Very good. And my bag?’

‘It will be up soon, sir. If you need any assistance in the future, just press the button and someone will be along to help.’

‘Thank you, young man. Any suggestions on what I should see first?’

‘There’s much to see and do throughout the first class, sir. Just two things to look out for. Stay away from the professional gamblers, and know where the doctors are, in case you get seasick. Beyond that, this is a luxury ship, sir, and we hope you enjoy your voyage.’

The steward accepted my tip with a quick salute and rushed back to the gangway to assist other passengers.

The ship was due to depart at noon, just minutes away. I left my cabin to witness this colourful event and to attempt to locate Holmes. I walked down the hallway and, instead of climbing the stairs to B Deck, decided to make use of the ship’s most modern convenience. One of the three lifts was already open, so I stepped inside the dark mahogany cage, which was occupied by several passengers and crew. Overhead, the large winding gear that moved the cage up and down was visible through a glass ceiling.

‘Most impressive,’ I told the lift operator, as he looked outside to check for other passengers.

‘Yes, sir, quite a new idea for liners.’

As he began to close the collapsible gate, I noticed a tall man in a naval uniform running towards us. I put out my hand to hold the gate back to let him in.

‘Thank you, friend,’ said the navy man, who seemed to smile and eye me suspiciously at the same time. He had an easy air of authority, which was suggested, perhaps, by his brisk Scottish accent. His hair, including his well-trimmed beard, was fully grey. As the lift ascended, he glanced at each of the passengers over the rim of his glasses. All seemed eager to leave as the gate opened on B Deck.

I climbed the stairs to the boat deck and saw that the rail was already lined with passengers, waving to friends and family on the dock below. Suddenly, the air vibrated from the booming sound of the ship’s huge whistles. The crowd on deck cried out with excitement and waved final farewells to their relatives and friends. The Titanic was preparing to depart.

‘It’s just about time,’ said a raspy voice to my left. ‘I see that they have singled up and we’ll be leaving in a minute or two.’

I turned and saw the naval officer standing next to me. His hands were folded behind him, with his head tilted back. Ignoring the crowd, he focused his attention on the layout of the ship and the crew’s preparations for departure.

‘It’s a very exciting moment, is it not?’ I replied. ‘That is...being on this grand ship as it begins its first voyage.’

‘Oh, I’ve headed out on more ships than I care to remember — Navy ships mostly. If you take away the fanfare and hoopla, one trip’s pretty much the same as the next.’

‘You’ve been at sea for a long time, then.’

‘All my life. Been on just about every type of ship — some in battle. I believe I know the sea as well as the next man.’

‘By the way, my name is Watson. Doctor John Watson. And you are...?’

‘Commodore Giles Winter of the Royal Navy. Pleased to meet you, Doctor.’

‘I cannot understand, for the life of me, why a Navy man would want to spend his holiday on a cruise. Or is this perhaps a business trip?’

‘Business. Just doing a routine evaluation of the vessel. I did the same thing on board the Titanic’s sister ship, Olympic. White Star has a third ship planned of the same design. In the event of war, we like to know the capabilities of all ships that are available. This ship, for example, could be useful as a troop carrier or hospital ship.’

‘That makes sense. But I must say, I’d just as soon not think of prospects like that on a day like this.’

‘And that, Doctor, is precisely my remit — to ensure that civilians like you can go about your lives without worrying about war.’

‘I assure you, Commodore, I have seen battle. In fact, while serving as an army surgeon in Afghanistan, I was seriously wounded at the Battle of Maiwand.’

‘Afghanistan, yes, that was a bad one, all right. But land wars just do not compare to sea battles, if you will forgive me saying so. There is nothing worse than having a ship sink under you. Your only hope is that your enemy will be generous enough to pull you out of the water.’

‘You know, you are as stubborn as a friend of mine. You may have heard of him, a detective of the name of Mr Sherlock Holmes.’

‘Holmes... So, you’re that Doctor Watson. I have read a few of those stories. He must be an extraordinary fellow, that Mr Holmes.’

‘Oh, I suppose so. But I have to confess, I exaggerated his talents a little, to create a better story, you understand.’

The commodore paused for a moment, considering this revelation. ‘Are you saying this Holmes was not the great detective you made him out to be?’

‘Oh, I’d say he was certainly a great detective but he had some flaws. For example, at times he was prone to exhibit over-confidence. And you know how I referred to him as a master of disguise? Well, he was not always in top form.’

‘What do you mean?’ he asked, narrowing his eyes to a cold stare.

‘Take that disguise you are wearing now. Did you really think that a beard, some hair dye and a disguised voice would fool an old friend?’

The commodore’s features remained the same. But there was something familiar in his laugh that confirmed that I was once again in the company of my friend, Mr Sherlock Holmes.