Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

In 1897, the world changed forever when our planet came under attack from Martian invaders. The world's greatest detective, Sherlock Holmes, along with his friend Professor Challenger embark on one of their most dangerous adventures to date... to discover the nature and intent of their extra-terrestrial attackers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 347

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

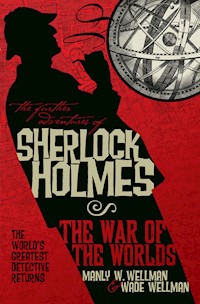

Thefurtheradventures of

SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

MANLY W. WELLMAN& WADE WELLMAN

TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

by Manley Wade Wellman & Wade Wellman

ISBN: 9781848564916

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First Titan edition: October 2009

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 1975, 2009 Manly Wade Wellman and Wade Wellman

Visit our website:

www.titanbooks.com

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address. To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive Titan offers online, please register as a member by clicking the ‘sign up’ button on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed in the USA.

AVAILABLE NOW FROM TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE ECTOPLASMIC MAN

Daniel Stashower

ISBN: 9781848564923

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

DR JEKYLL AND MR HOLMES

Loren D. Estleman

ISBN: 9781848567474

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE MAN FROM HELL

Barrie Roberts

ISBN: 9781848565081

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE SCROLL OF THE DEAD

David Stuart Davies

ISBN: 9781848564930

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

SÉANCE FOR A VAMPIRE

Fred Saberhagen

ISBN: 9781848566774

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE SEVENTH BULLET

Daniel D. Victor

ISBN: 9781848566767

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE STALWART COMPANIONS

H. Paul Jeffers

ISBN: 9781848565098

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE VEILED DETECTIVE

David Stuart Davies

ISBN: 9781848564909

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

Manly Wade Wellman & Wade Wellman

ISBN: 9781848564916

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE WHITECHAPEL HORRORS

Edward B. Hanna

ISBN: 9781848567498

COMING SOON FROM TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE ANGEL OF THE OPERA

Sam Siciliano

ISBN: 9781848568617

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE GIANT RAT OF SUMATRA

Richard L. Boyer

ISBN: 9781848568600

Two Authors’ Notes

In the summer of 1968 I was fortunate enough to see A Study in Terror, a splendid movie involving Sherlock Holmes pitted against Jack the Ripper in London around 1890. This is the only film I have ever seen in which the magnificent speed of Holmes’s thinking is brought to life with full effect. So effective was the portrayal of Holmes that, as I saw the film for the first time, I suddenly began to ask myself — wondering, indeed, why I had never thought of it before — how Holmes might have reacted to H. G. Wells’s Martian invasion. I determined to write a story on this subject and, since I am primarily a poet, felt obliged to ask for assistance. My father agreed to collaborate, suggesting that another Doyle character, Professor Challenger, be included. Our collaboration, ‘The Adventure of the Martian Client’, was published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction for December, 1969.

I then felt that more could be done with the idea and suggested a sequel. Our second story, ‘Venus, Mars, and Baker Street’, appeared in the same magazine for March, 1972. After it appeared, I decided that the account of Holmes’s activities in the first ten days of the invasion was far too brief, and that a third story, a sort of inverted sequel, must also be written. By the time this was purchased, we determined to turn the saga into a book, which we now offer to the public, with some additions and revisions.

Incidentally, it seems evident that Wells’s The War of the Worlds was to some extent influenced by Guy de Maupassant’s ‘The Horla’, although the influence has never, to my knowledge, been observed by a critic. Readers of this saga should take notice of an excellent moving picture, loosely based upon de Maupassant’s tale, Diary of a Madman. The bad title has damaged the film’s reputation, but the title character, superbly played by Vincent Price, is a man who outwits and destroys a superior being in a fashion well worthy of Holmes. Two motion pictures, then, have played their parts in the various inspirations for these five tales.

I dedicate my part of the saga to my friend Bob Myers, in warm appreciation of the courage, resolution, compassion, and humor which are so nobly outstanding in his character and personality.

Wade Wellman,Milwaukee, Wisconsin

My partner in this enterprise says he found inspiration while pondering two motion pictures, which I have not seen and cannot judge. But he vividly imagined Sherlock Holmes in The War of the Worlds for both of us. We have seen publication of our short stories about it, and we feel that the whole story was not told. Here is the effort to tell it.

Wells’s novel was serialized in Pearson’s Magazine, April-December, 1897, and published as a book in London and New York the following January. But Wells spoke from a time in the then future, dating the invasion as “six years ago”. My partner, a better astrologer than I, pointed out that the only logical year of the disaster was 1902, in June of which year Mars came properly close to earth; which supplies for us the necessary dates for the other corridor of time in which these things happen, including Wells’s view-point as of 1908 and publication presumably late that year or early in 1909.

All our labors would be plagiarism, did we not make positive and grateful acknowledgment to Wells’s The War of the Worlds and his short story, ‘The Crystal Egg’, which is a supplement to the novel; similarly to the whole Sherlock Holmes canon and to Doyle’s The Lost World and other stories about the fascinatingly self-assured George Edward Challenger. Sherlockians both, we have also consulted with profit numerous works in the field and have found particular value in William Baring-Gould’s exhaustive and scholarly The Chronological Holmes.

If I may dedicate my share of the present work, let me do so to the memories of the inspiring Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Herbert George Wells.

Manly Wade Wellman,Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Contents

Introduction

I. THE ADVENTURE OF THE CRYSTAL EGG

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

II. SHERLOCK HOLMES VERSUS MARS

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

III. GEORGE E. CHALLENGER VERSUS MARS

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

IV. THE ADVENTURE OF THE MARTIAN CLIENT

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

V. VENUS, MARS, AND BAKER STREET

Twenty-One

Twenty -two

Twenty—Three

Twenty-four

Appendix

Introduction

The distinguished career of Sir Edward Dunn Malone in journalism and literature, as well as his brilliantly heroic service in both World Wars, is too well known to need review here. The present volume contains certain of his previously unpublished writings, recently brought to our attention by his literary executor.

His account of some aspects of the so-called “War of the Worlds”, anonymously published some years ago under the title of Sherlock Holmes Versus Mars, now proves to be a greatly modified and abridged version of the original essay found among his private papers. Sir Edward’s private correspondence reveals some displeasure at that modification, and it would seem that his fear of similar treatment dissuaded him from offering for publication two other studies of the same event. We have therefore decided to publish the three essays — two of them never published before, the other one presented only in condensed form — as a connected narrative.

It has been thought appropriate to add to them two other accounts by John H. Watson, M.D., which also were previously published in abridged and modified form. In the interests of making the collection more or less complete, there is further included Dr Watson’s letter to Mr Herbert George Wells, which first appeared as a postscript to the anonymous Sherlock Holmes Versus Mars, but which we here offer as the final section of the volume, in the interests of historical continuity.

I

THE ADVENTURE OF THE CRYSTAL EGG

BY EDWARD DUNN MALONE

One

It was one of the least impressive shop fronts in Great Portland Street. Above the iron-clasped door was a sign, ART AND ANTIQUITIES. In one of the two small windows with heavily leaded panes a card said RARE ITEMS BOUGHT AND SOLD. The tall man in the checked ulster gazed at this information, then walked in from the cold December afternoon.

The interior was like a gloomy grotto, its only light a shaded lamp on a rear counter. The shelves were crowded with vases, cups, and old books. On the walls hung sooty pictures in battered frames. The tall man paused beside a table strewn with odds and ends and bearing a placard reading FROM THE COLLECTION OF C. CAVE. From an inner door appeared the proprietor, medium-sized, frock-coated, partially bald. “Yes, sir?” he said.

“I hope to meet someone here, Mr Templeton,” said the other. His hawklike face bent above the table. “What are these articles?”

“Another dealer in antiquities died two weeks back. I took these things when his shop was sold up.”

The visitor picked up a crystal as big as his fist, egg-shaped and beautifully polished. A ray from the lamp kindled blue flame within it. “What do you ask for this?”

“Cave priced it at five pounds.”

“I’ll pay that for it.” A slim white hand flung back the ulster and from an inside pocket of the gray suit drew a pocketbook and produced a five-pound note. “Don’t bother to wrap it.”

As the purchaser stowed the crystal in his ulster pocket, another customer came through the front door. He was short and shabby, with truculently bristling gray hair. He stopped and stared at the tall man with suddenly wide eyes.

“Templeton,” he blurted out, “did you bring Sherlock Holmes here?”

“I came of my own volition, Hudson,” said Holmes coolly. “You have conjectured that I had come to anticipate you. Your powers of deduction, though slight, should tell you the reason for my presence.”

“This is Sherlock Holmes?” Templeton was stammering. “Hudson, I assure you I did not know—”

“Nor did Morse Hudson know,” interrupted Holmes. “I sought him here on behalf of young Mr Fairdale Hobbs, whose Cellini ring was stolen.”

“You can’t prove I took it from him,” blustered Hudson.

“My small but efficient organisation has helped me trace it to your possession. Mr Templeton here should be wary of receiving stolen goods, and I will relieve him of such an embarrassment. I see the ring on your forefinger.” Holmes extended his hand. “Give it to me at once.”

Hudson swelled with fury, but he tugged the ring free and handed it over. “You’re a devil, and no other word for it,” he muttered.

“I am a consulting detective, which may mean the same thing to your sort,” said Holmes, sliding the ring into the pocket of his waistcoat.

Hudson blinked at Templeton. “Where’s that crystal egg?” he demanded. “I heard from a Mr Wace about it.”

“I have just bought it for five pounds,” Holmes informed him, smiling. “I wonder, Hudson, how a man of your wretchedly dull esthetic sense could see the beauty of that object.”

“You know about it,” charged Hudson, glaring. “Shall I tell Templeton here some interesting private matters about you?”

“Do so, if you want me to tell the police some interesting matters about yourself. Suppose you keep silent and hope that I do likewise. I have recovered my client’s property so easily that I feel disposed to let the matter rest.”

He walked out. Hudson bustled after him into the chilly street.

“I demand that you sell me that crystal for five pounds, Mr Holmes.”

“You’re in no position to demand anything of me, Hudson,” Holmes said quietly, “but let me give you a word of advice. If ever again you prowl this close to Baker Street below here, for whatever reason, that day will see your shop filled with coldly suspicious men from Scotland Yard, and you will watch its sun set through the bars of a cell. Is that sufficiently clear? I daresay it is.”

He signaled a hansom and got in, leaving Hudson to glower helplessly in the wintry air, and rode to the lodgings of Fairdale Hobbs in Great Orme Street near the British Museum. Hobbs was a plump young man, wildly grateful for the return of the ring. It was a family heirloom, he said, and had been promised to the girl he meant to marry. “You recovered it in less than twelve hours,” he chattered as he paid out Holmes’ fee. “Marvellous!”

“Elementary,” Holmes replied, smiling.

Back at his rooms in Baker Street, he rang for Billy, the page boy, and gave him a handful of silver. “Circulate these shillings among the Baker Street Irregulars and give them thanks for tracing that lost ring.”

“We’ve learned something else, Mr Holmes,” said Billy. “Morse Hudson has moved into a new shop. He was heard telling old Templeton that he wanted to get away from your investigations.”

“Once I suggested that move to him,” nodded Holmes. “Amusing, Billy, how even my enemies act on my advice.”

Billy hurried away. Holmes hung up his ulster and took the crystal from its pocket. He had thought of giving it to Martha for Christmas; she loved beautiful things to put on her shelves. But why had Hudson been so interested? Sitting down, Holmes studied it. Again he saw a gleam of misty blue light within it, shot through with streaks of rosy red and bright gold. This way and that he turned the crystal. At last he drew the curtains to darken the room and again sat down to look at his purchase more narrowly.

At once he found himself sitting eagerly forward and straining his eyes to see better. The blue light had grown stronger, and it seemed to stir, to ripple, like agitated waters. Tiny sparks and streaks of light moved in it, brighter red and gold, with green as well, swirling like a view in a kaleidoscope. Then there was a clearing of the mist, and for a moment Holmes glimpsed something like a faraway landscape.

It was as though he looked down from a great height across a plain. Afar in the distance rose a close-set range of blocky heights, red as terracotta. Closer, more directly below, stretched a rectangular expanse, as though of a dark platform. To the side he made out a sort of lawn, light, fluffy green, through which the reddish soil was visible. Then the misty blue returned, blotting out the vision.

A soft knock at the door, and a key turning. Quickly Holmes leaned down to set the crystal in the shadows beside his chair and rose. His landlady came in. She was tall, blond, of superb figure and her red lips and blue eyes smiled. He moved toward her and they kissed.

“Dr Watson is gone to the theatre,” she said, “and I thought I would bring in dinner for the two of us.”

“Excellent, my dear,” said Holmes, drawing her close with his lean arm. “I have been thinking about Christmas for you. I have even decided what I shall give you.”

“This first Christmas of the new century,” she said. “But should you tell me so far ahead?”

“Ah,” and he smiled, “you are breathless to know. Well, that Cellini ring I found for Mr Fairdale Hobbs is a striking little jewel. What if I should have it duplicated for you?”

“You are too good to me, my darling.”

“Never good enough. All right, fetch us our dinner.”

She was gone. Holmes went to the telephone and called a number. A voice answered. “Let me speak to Professor Challenger,” said Holmes.

“This is Professor Challenger,” the voice growled back fiercely. “Who the devil are you, and what the devil do you want?”

“This is Sherlock Holmes.”

“Oh,” the voice rang louder still, “Holmes, my dear fellow, I had no wish to be abrupt, but I am in the midst of an important work, irritating in some aspects. And I have been bothered by journalists. What can I do for you?”

“There’s a curious problem I would like to discuss with you.”

“Certainly, any time you say,” bawled back Challenger’s voice. “You are one of the few, the very few, citizens of London whose conversation is at all profitable to one of my mental powers and professional attainments. Tomorrow morning, perhaps?”

“Suppose we say ten o’clock.”

Holmes hung up as Martha Hudson fetched in a tray laden with dishes.

Two

Next morning Holmes took a cab to West Kensington and mounted the steps of Enmore Park, Challenger’s house with its massive portico. A leathery-faced manservant admitted him and led him along the hall to an inner door, where Holmes knocked. “Come in,” came a roar, and Holmes entered a spacious study. There were shelves stacked with books and scientific instruments. Behind the broad table sat Challenger, a squat man with tremendous shoulders and chest and a shaggy beard such as was worn by ancient Assyrian monarchs. In one great, hairy hand was cramped a pen. He gazed up at Holmes with deep-lidded blue eyes.

“Let us hope that I am not interrupting one of your brilliant scientific labours,” said Holmes.

“Oh, it is virtually finished in rough draft.” Challenger flung down the pen. “A paper I am going to read at the Vienna meeting, which will hold up to scorn some of the shabby claims of the Weissmanist theory-mongers. Meanwhile, I am prepared to devote an hour or so to whatever problem may be puzzling you.”

“As you were able to help me so splendidly in the matter of the Matilda Briggs and the giant rat of Sumatra.”

“That was nothing, my dear Holmes, a mere scientific rationalisation of a fortunately rare species. What is it this time?”

Holmes produced the crystal and told of his experience with it the night before. Challenger took the object in his mighty paw and bent his tufted brows to look.

“There does seem to be some sort of inner illumination,” he nodded, frowning. “Will you pull the curtains? I think darkness will help.”

Holmes drew the heavy draperies, plunging the room into deep shadow, and returned to look over Challenger’s mighty shoulder.

“It has the appearance of a translucent mist, working and rippling,” said the professor. “Almost liquescent in its aspect.”

“‘Charmed magic casements, opening on the foam of perilous seas, in faerie lands forlorn,’” said Holmes under his breath.

“Eh?” The bearded face swung around. “What are you saying? What has that drivel to do with the matter?”

“I was quoting a poem,” said Holmes.

“Which strikes me as singularly lacking in merit.”

Holmes smiled. “It is by John Keats.”

“Indeed?” sniffed Challenger. “Well, I have never pretended to critical judgement in matters of that sort. In any case, we have no seas here, but a terrain. Look, Holmes.”

He had taken a dark cloth from a drawer and cradled the crystal in it. Again the soft radiance of the mist had cleared, and they looked on the landscape which Holmes had seen the previous night.

It was like peering through the wrong end of a telescope, a view small but vivid. There was the great stretch of ground, the distant red-brown bluffs and, below in the foreground, an assembly of rectangles that seemed to be vast, flat roofs. Things moved there, and among the tufts of shrubbery on the sward alongside. Straight ahead, in an ordered row, sprouted up a series of lean masts, each tipped with a glare of radiance, like a bit of sunlit ice.

“Beautiful” said Holmes, enraptured despite himself. “Unearthly”

“Unearthly is an apt description of it” muttered Challenger. “No such scene exists in any land upon Earth that ever I heard report of.”

The vista fogged over a moment, then cleared again. Now they were aware of what the moving things were. On the ground they seemed to creep like gigantic beetles with glittering scales, while closer at hand, on the roof, several small rounded objects moved here and there. Then, among the masts straight ahead, a flying something, like a moth or bat, appeared. It swooped close, and suddenly a face looked from within the crystal.

Holmes had the impression of wide, round eyes staring deeply into his. Next moment it was gone, and the whole vision with it. Only blue mist churned in the crystal.

“Did you see it, Holmes?” said Challenger, springing up to draw back the draperies.

“I did indeed. Here, I’ll write down what I saw on this pad. You might do the same.”

Holmes drew a chair to the table, sat down and wrote swiftly. Challenger snorted over his own hurried scribbling. Both were silent for some moments, then exchanged pads. Each read the words the other had put down.

“Then it was no illusion,” said Challenger. “We saw substantially the same objects. Perhaps my eye is more scientifically trained, better qualified to observe, but you have written down the rooftop and the remote system of cliffs and the presence of moving, living things. It is now our task to rationalise what this crystal has shown us.”

“Some representation of another planet, I increasingly suspect,” said Holmes.

“I am tempted to the same suggestion.” Again Challenger turned the crystal over and over. “If this is an artificial semblance inside, like those Easter eggs children love to look into, it is an amazingly elaborate and impressive illusion.”

“Keep turning the crystal in various positions,” said Holmes. “See if the viewpoint remains the same.”

They experimented for some time, with varying success. It became evident that by turning the crystal they could somewhat change viewpoint, shifting the direction here and there above the great expanse of flat roofs and across the surrounding landscape, but visibility blurred, then blurred again. At times it faded completely.

“Would things be more visible if we had complete darkness?” Holmes wondered.

“Possibly so. I’ll try to achieve that condition later on. At present, I am considering your suggestion that the scenery is extraterrestrial. I can neither confirm nor deny it.”

“I remind you that it is only a suggestion, not a deduction,” said Holmes. “Wherever the place may be, however, it seems certain that we are looking down upon it from one of the tall masts, at the very end of the row.”

“I have a similar impression,” agreed Challenger.

“I fear I must leave you now,” said Holmes rising.

“My presence is required elsewhere. But let us make further studies, by all means.”

“That was unnecessary to urge upon me.”

As Holmes went out, Challenger crouched above the crystal in almost a fury of concentration.

Holmes took a cab to Scotland Yard, where he was able to offer considered opinions on two difficult cases. Returning to his rooms, he busied himself with making notes on the two problems, pushing the crystal to the back of his mind. He and Watson had dinner together and talked in friendly fashion, but Holmes said nothing of the crystal.

Next morning, Watson departed to make several professional calls. Holmes visited Scotland Yard again and conferred with two inspectors. When he returned home early in the afternoon, he found Challenger in the sitting room, tramping up and down as though frenzied with excitement.

“Your landlady let me in when I assured her of the enormous importance of my visit,” Challenger greeted Holmes. “Extraordinarily fine woman, that landlady. The sort with a gift of deep feeling — brilliant feeling, I should judge. There are brilliances of feeling as there are of mind.”

“Yes,” said Holmes quietly.

“But I am here to report concerning our crystal,” Challenger hurried on. “Holmes, you were right. I have vindicated your suggestion that the scenes it shows are extraterrestrial. I have even identified the planet.”

“Amazing, my dear Challenger!” cried Holmes.

“You will find it elementary, my dear Holmes. The suggestion that I study it in absolute darkness proved a fruitful one. I took a black cloth such as photographers use and draped it so as to shut out almost all the light. I saw more clearly than when you were there this morning. Night had fallen over that landscape, the stars were out — and that is when a highly important truth, nay, a staggering one, revealed itself.”

“And what was the truth?” asked Holmes.

Challenger drew himself up dramatically. “The stars were out, I say, in the sky above that roof with the towers. I made out Ursa Major, the Great Bear. What does that suggest to you?”

“That, if it is on a world other than ours, it is close enough so that the same constellations are visible.”

“The constellations are the same, yes, but what followed was vastly different and conclusive. Two moons presently rose above the horizon — not one moon, but two. Both were very small, markedly jagged, and one of them moved so swiftly that I could see its progression. As they rose high, they vanished from sight.” Challenger drove a fist into the palm of his other hand. “Do you see what that means?”

“I believe I do,” said Holmes gravely. “If you saw the Great Bear, you saw the skies from within the solar system. And two moons — the only planet near us that has two moons is Mars.”

“You are right, Holmes,” nodded Challenger energetically. “This is proof that we are able to see a Martian landscape.”

“‘Proof palpable as the bright sun,’” said Holmes. “You must forgive me, Challenger, if I quote Keats again — this time from Otho the Great.”

Challenger sat down heavily and puffed out his bearded cheeks. “You will do me the justice of believing that I have read and appreciated poetry in the past, before the direction of my researches came to demand so much of my time. Of the Romantics I preferred Shelley, precisely because of his own interest in scientific subjects. Even in my literary tastes, I have cultivated the purely scientific mind.”

“And I have aimed rather at the universal mind,” said Holmes, “But you are right, Shelley was the most scientific in his interests among the Romantics.”

“He was keenly interested in astronomy, and the subject now before us is certainly astronomical.”

A knock at the door. Billy looked in. “Someone to see you, Mr Holmes,” he said, and Templeton entered, carrying a shabby top hat in his hand. He seemed nervous and apologetic.

“If you are engaged at present, Mr Holmes—” he began uneasily.

“I can spare you a moment. What is it?”

“It’s about that crystal, sir. I’ve found out that it is worth far more than the five pounds you paid me.”

“You accepted five pounds,” said Holmes bleakly. “You have come a bit too late to raise the price.”

“But Morse Hudson tells me that others will bid high for it,” pleaded Templeton. “A Mr Jacoby Wace, Assistant Demonstrator at St Catherine’s Hospital, and the Prince of Bosso-Kuni in Java. Hudson says they both have money. If we get a profit from one or the other, you and Hudson and I could divide it.”

“Templeton,” said Holmes sternly, “you endanger yourself by associating with Morse Hudson. Had he not surrendered the Cellini ring to me in your shop, you might have been guilty of receiving stolen goods. As for the crystal, be content to realise that it is no longer in my possession.”

“Mr Holmes is telling you the truth, my good man,” rumbled Challenger.

Templeton gazed wide-eyed at Challenger. “How am I to know that, sir? I do not believe I am acquainted with you—”

“Does this fellow doubt my word!” roared Challenger, bounding to his feet. “You are addressing George Edward Challenger, sir! Here, Holmes, stand aside while I throw him down the stairs.”

Templeton flew out through the door like a frightened rabbit. Challenger sat down again, his face crimson.

“So much for that inconsequential interruption,” he said. “Now, Holmes, it is our duty to consider all implications. First of all, we must speak of the crystal to nobody.”

“Nobody?” repeated Holmes. “You do not want other scientific opinions?”

“Bah!” Challenger gestured impatiently. “I have had experience of such things. A revolutionary new idea stuns them, impels them to make ridiculous, offensive remarks. At present, keep it our secret.”

“My friend Watson is a doctor, has scientific acumen,” said Holmes. “I have always found him respectful and ready to be enlightened. Some day you and he must meet.”

“No, not even your friend Watson. I shall not tell my wife. And I trust you will not tell your landlady.”

“Why do you admonish me about that?”

Challenger’s blue eyes regarded Holmes intently. “I give myself to wonder if you cannot best answer that question yourself. But meanwhile, we must continue our observations, checking each against the other. When can you come to Enmore Park?”

“Later this afternoon,” said Holmes.

“Shall we say four o’clock? I have an errand, but I can dispose of it by then.”

Challenger donned his greatcoat and tramped out. Holmes sat at his desk, brooding. He picked up a pen, then laid it aside. A knock at the door, and Martha entered.

“You haven’t had any luncheon, my dear,” she said.

“A correct deduction, but how did you know?”

“Because I know your habits. You never take care of yourself when you are deep in a problem. Before I bring the tray in, will you tell me what you and Professor Challenger were discussing?”

“We spoke about poetry, among other things,” replied Holmes.

She smiled. “You have written some poems to me. Beautiful poems.”

“At least inspired by a splendid subject.”

She went out and returned in a few minutes, bringing their lunch. Holmes was writing at the desk. He laid down his pen, put away his notes in a drawer, and joined her at the table.

Three

At Enmore Park later that afternoon, Holmes and Challenger sat down at the table in the study with the crystal before them. Over their heads they drew a closely woven black cloth that excluded nearly all outer light. At once the crystal glowed with its inner blue radiance, lighting up Holmes’ intent profile and Challenger’s bristling beard. Challenger carefully maneuvered the crystal between his hands.

“There,” he said softly. “Do you see the mists clearing?”

The strange landscape was coming into view. They could make out the distant tawny-red cliffs, the great platformlike expanse below them. Then, as details grew sharper, they saw the row of lean, towering masts with their points of radiance. A clear, pale sun shown in the deep blue of the cloudless sky.

“That sun is but half the diameter of ours,” said Challenger. “At its closest approach, Mars is about thirty-five million miles beyond Earth’s orbit. If we take the Sun’s apparent diameter into consideration, we may arrive at some scale of dimension in what we see here.”

“I would judge the visible terrain to be many miles in extent, and this rectangle of roofs below the masts to be fairly large,” said Holmes

“We may go on that assumption,” said Challenger. “Now, watch closely.” He shifted the crystal with painstaking care. “We are able to see in another direction now, as though we moved a viewing glass.”

It was true. They looked downward past the straight edge of the platform and gathered a sense of a perpendicular wall below it. The ground showed, lightly covered with green as with a lawn, and feathery shrubs or bushes grew in clumps here and there. Among these clumps moved dark shapes. They seemed like distant bulbs of darkness, furnished with spidery limbs.

“It is as though we are above the closely set roofs of a city,” said Holmes. “I would hazard that our point of view is the top of the mast at the end of this row we have seen. And down there on the ground are what must be the residents. I wish we could see them closer at hand.”

“Perhaps we can.” Again Challenger shifted the crystal. “Now, observe the rooftop immediately below. I can discern others.”

At the foot of one of the nearer masts moved several of the creatures. Seen nearer at hand, they displayed oval bodies, dark and softly shining, holding themselves erect on tussocklike arrangements of slender tentacles.

“They strongly resemble octopoid mollusca,” said Challenger. “But see, Holmes, some of them can fly.”

One of the shapes on the roof suddenly rose into the air. It soared, or skimmed, on what appeared to be ribbed wings. Higher it rose, growing larger to their view.

“It does not move its wings,” said Holmes.

“They seem to be simple structures.”

The flying creature changed direction and swooped toward the top of the mast nearest the point from which Holmes and Challenger seemed to watch. Its two sprays of tentacles twined around the mast and the body drew close to the shining object at the apex.

“It has brilliant eyes, there at its lower part,” Challenger half-whispered, his voice strangely touched by awe. “Those eyes, when I have seen them, have stared with a marked intensity. Now it is looking into that shining object, it gazes fixedly.”

The creature clung there for long moments. Silently the two observers studied it. At last it relaxed its hold and came floating toward them in the crystal, growing in size, growing in detail. Close at hand they saw its gleaming eyes, and suddenly those eyes came as though against the opposite side of the crystal, the substance of the creature blotting out all the rest of the scene. Then, abruptly, the mist came stealing back, obscuring everything.

Challenger flung aside the cloth. He gazed at Holmes.

“We are in communication with Mars,” he said dramatically.

“Communication?”

Challenger’s hand scrambled for a pad of paper. He jabbed a pen into the inkwell. “Before another moment passes, we must both record what we have seen,” he pronounced. “There are materials for you.”

Silence, while both of them wrote. At last they finished and looked at each other again.

“A city, a Martian city, has been revealed to us,” burst out Challenger. “And we have seen living Martians. I have written here,” and he drummed his notes, “that they seem to be of a vastly different species from ours. Perhaps something to be referred, for comparison’s sake, to the arthropods — the insects.”

“Why the insects?” asked Holmes.

“Their form, for one aspect. Many thin appendages and soft muscular bodies. And you have seen that some have wings and some have not.”

“From my limited observation, I would not be surprised to establish that some of them at least can fly. But they may all have that capacity.”

“No, manifestly the power of flight is far from universal,” Challenger flung back impatiently. “Indeed, the presence or absence of wings may well be a difference of the sexes — the females may be winged, and the males not.”

“I have no basis of argument as yet, but I wonder if the Martians have not evolved to the point of sexlessness,” said Holmes, studying what he himself had written. “The wings may be artificial.”

“Nonsense!” exploded Challenger. “If they are artificial, would they not be attached with a harness? I saw nothing like that, nor, I suggest, did you.”

“They may well have other ways of assuming their flying apparatus than with a visible harness,” said Holmes quietly. “Reflect, Challenger, that this is another world on which they live, apparently with a tremendously complicated culture of their own.”

Challenger subsided, locking his shaggy brows in thought. “You may be right, Holmes,” he said at last. “It is not often that I feel obliged to retreat from a position.”

“You are generous to give way,” replied Holmes smiling. “Earlier today, you spoke disparagingly of other scientists who cannot do that. But let us consider another point for the moment. Our view seems to be from the top of a mast, and twice we have seen one of those creatures coming near and seeming to look into our very faces, as it were. We have also noted the glints of light on the other masts. Might it not follow that on top of our mast is some device similar to this very crystal we have here? And that a view through that crystal gives them a look through this one at us, as a view from this one gives us a look at them?”

“Indeed, what else?” demanded Challenger triumphantly, as though he himself had come up with the theory. “It is no more than sound logic, Holmes. On top of that mast on Mars is a contrivance which in some way is powered to observe across space to the area where this crystal is located on our own planet — to this very study.”

“As one telegraphic instrument communicates with another, although the procedure is far more subtle than that,” said Holmes. “And these creatures on Mars may be far ahead of humanity, in more than mechanics.”

Challenger grimaced in his beard. “Next you will be suggesting that they are a biological advance on the human race, an evolutionary development.”

“What I have seen suggests that something of the sort has happened on Mars, over a long period of time. You saw them, Challenger. Those oval bodies must house massive brains. And their limbs, two tufts of tentacles. Might these not be a latter-day development of two hands?”

“That is brilliant, Holmes!” Challenger’s fist smote the table so heavily that the crystal rocked. “You may well have the right of it,” and he began to scribble again as he talked. “Specialised development of the head and the hands. Nature’s two triumphs of the superior intellect. Yes, and a corresponding diminution of other organs, less necessary to their way of life — atrophy of the lower limbs, for instance, as has occurred with the whale.” He looked up again. “Truly, Holmes, I begin to think that you would have done well to devote yourself to the pure sciences.”

Holmes smiled. “Instead of devoting myself to life and its complexities? I have trained myself to the science of deduction, which develops an ability to observe and to organise observations.”

Challenger cocked his great head. “I must repeat, Holmes, we must keep these matters to ourselves for the present. If you will let me develop my reasons for insisting—”

“No, permit me to offer one of my deductions,” put in Holmes. “You hesitate to confront your fellow scientists lest they jeer at you, charge you with reckless judgements, even with charlatanism.”

Challenger’s stare grew wider. “I may have hinted something like that, but your interesting rationalisation is perfectly correct.”

“It offered me no difficulty,” said Holmes. “In my ledgers at home, under the letter C, are several newspaper accounts that deal with your career. One of the most interesting of them describes your emphatic resignation in 1893 as Assistant Keeper of the Comparative Anthropology Department at the British Museum. There was considerable notice, with quotations, of your sharp differences with the museum heads.”

“Oh, that.” Challenger gestured ponderously. “That is water under the bridge, of a particularly noisome sort. At any rate, I have not quarreled with you. Now, suppose we ask my wife to give us some tea, and then we will return to our observations here.”

Tea was a pleasant relaxation, and Mrs Challenger proved a charming hostess. Half an hour later, the two were in the study again, their heads draped with the black cloth. They gazed at what the crystal showed them of the rooftop, the masts, the lawn below, and the strange creatures that moved here and there. Repeatedly they saw different Martians leave the ground to fly. Finally one of them discarded its wings in their sight. Challenger uttered a loud exclamation.

“You are right, Holmes!” he cried. “The wings are artificial. I am fully convinced.”

“Which disposes of them as sexual characteristics,” said Holmes.

“Yes, of course. And I can observe in them no physical differences such as denote sexual differences to the zoologist.” He breathed deeply. “But why was this crystal sent here to Earth?”

“And how?” asked Holmes in his turn.

Challenger threw back the cloth. “By some strange method we cannot understand, any more than African savages understand a railroad train.”

“For what purpose?”

“Manifestly to watch us,” said Challenger. “It was a triumph of extraterrestrial science, sending it thirty million miles or more across space.”

“If it could cross space, might not living Martians follow suit?”

“An expedition here?” said Challenger. “For what purpose?”

“I wonder,” said Holmes slowly. “I wonder.”

Four

T