Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Terror reigns on the streets of Whitechapel where horrific murders are being committed. SHERLOCK HOLMES believes he knows the identity of the killer - Jack the Ripper. But as he delves deeper, Holmes realizes that revealing the murderer puts much more at stake than merely putting a psychopath behind bars. In this case, Holmes is faced with the greatest dilemma of his career.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 718

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AVAILABLE NOW FROM TITAN BOOKS:

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES SERIES

THE ECTOPLASMIC MAN

Daniel Stashower

THE SCROLL OF THE DEAD

David Stuart Davies

THE STALWART COMPANIONS

H. Paul Jeffers

THE VEILED DETECTIVE

David Stuart Davies

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

Manley Wade Wellman & Wade Wellman

THE MAN FROM HELL

Barrie Roberts

THE SEVENTH BULLET

Daniel D. Victor

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HOLMES

Loren D. Estleman

COMING SOON FROM TITAN BOOKS:

THE GIANT RAT OF SUMATRA

Richard L. Boyer

THE ANGEL OF THE OPERA

Sam Siciliano

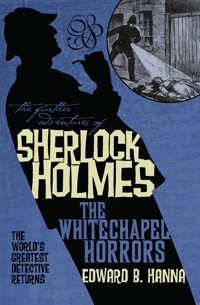

The further adventures of

SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE WHITECHAPEL HORRORS

EDWARD B. HANNA

TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES:

THE WHITECHAPEL HORRORS

ISBN: 9781848569225

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First edition: October 2010

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 1992, 2010 Edward B. Hanna

Visit our website:

www.titanbooks.com

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address. To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive Titan offers online, please sign-up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the USA.

“To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman. I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex.” — A Scandal in Bohemia

For Marcia, the woman in my life

Contents

Foreword

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Notes

Mea Culpa

Foreword

Edward B. Hanna was a dedicated bibliophile. He had thousands of books on hundreds of subjects, not the least of which was the work of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

He was most in his element surrounded by the written word and steeped in history. In the later years of his life he researched and wrote in the privacy of his study with his patient cat, Mystère, distracting him only to remind him that it was dinnertime.

Always the harshest critic of his own work, he constantly wrote, rewrote and destroyed his work. He spoke of his book subjects to no one, saying that when shared he lost interest in his subjects.

When Hanna completed The Whitechapel Horrors, he revealed to his beloved wife that the ending surprised him. Hanna had a certain conclusion in mind when he began the book, however, the writing of the tale of Mr. Holmes and Dr. Watson took on its own life. It is fair to say that in the composition of this work the characters became alive for Hanna and created their own destiny.

I hope that you find enjoyment from The Whitechapel Horrors.

Leigh Hanna

March 2010

Prologue

“Somewhere in the vaults of the bank of Cox & Company, at Charing Cross, there is a travel-worn and battered tin dispatch-box with my name, John H. Watson, M.D., Late Indian Army, painted on the lid.”

— The Problem of Thor Bridge

One of the first official acts of Mr. Ronald F. Jones upon taking up his new position as director and general manager of London’s venerable Claridge’s was to inspect the contents of the safe in his office. There were two surprises.

The first was an unopened basquaise, or flat, long-necked flagon of very old and equally fine Armagnac, a Reserve d’Artagnan, if the faded label was to be believed.

The second was a thick leather portfolio, also very old and once very fine, with the initials JHW embossed in faded gold leaf in the center.

The presence of the Armagnac has never been explained; it had been there when Mr. Jones’s predecessor arrived many years before and, as far as he knew when queried, when his predecessor arrived many years before him.

The leather portfolio was more easily explained. It had been left in the care of Claridge’s management by a gentleman who had been a permanent resident for as long as even the oldest staff member could recall. He was a retired surgeon by the name of Anstruther who, being a childless widower and the last of his line, had no family, and being quite elderly, had outlived all of his friends and contemporaries.

It seems that Mr. Anstruther had little faith in banks, having lost a sizable part of a large inheritance during the Great Depression, and no trust in the legal profession, upon which he blamed most of the ills of the world (“First, kill all the lawyers,” he was fond of misquoting Shakespeare). Therefore, he chose the strongbox of Claridge’s, which he considered the second safest depository in all of England. Banks could fail, Britain could lose her Empire, but Claridge’s? Claridge’s would remain unchanged, untouched, untroubled for as long as that other great monument to the English race and Western civilization, the Tower of London. And since its vaults were otherwise occupied, Claridge’s safe would simply have to do.

But then one day old Mr. Anstruther died, and the worn, cracked leather portfolio remained quite forgotten until the occasion, several years later, when Mr. Jones took up his new position.

Having more pressing matters on his mind at that time, it was not until a number of months had passed and Mr. Jones once again had occasion to rummage through the contents of the safe, that the presence of the portfolio (and the Armagnac) came to mind. The temptation to open both came upon him, the portfolio because he was curious, the Armagnac because it had been a particularly arduous day. But one just doesn’t break the seals of a bottle of old and rare brandy on a whim or without proper occasion, especially since it had remained undisturbed in its sanctuary for how many years? Its very presence, though known to few, had become as much a part of Claridge’s as the marble and mahogany and gleaming brass of the public rooms, and though there was little likelihood of a rightful owner returning to reclaim it, or of some hidebound traditionalist writing an indignant letter to The Times, good form and Mr. Jones’s integrity demanded the bottle be returned undisturbed to its place of rest. Besides, if the truth be known, he was really partial to cognac.

The portfolio? Ah, well, that was another matter.

The topmost document was a letter, a sheet of heavy foolscap yellowed with age, bearing the logotype of Cox & Company, Charing Cross, London. It was dated July 30, 1929, and was addressed to Mr. Elwyn Anstruther, F.R.C.S., Harley Street. At first reading the brief contents were uninteresting, disappointing, a dry and formal communication from banker to client.

Dear Sir:

I have to inform you of the unfortunate death, on the 24th instant, of Dr. John Hamish Watson, an honored client of Cox & Company of many years standing.

It had been Dr. Watson’s custom, from time to time, to entrust to our safekeeping various notes and records of a confidential nature, the contents of which I, naturally, have no knowledge. It was his wish, as expressed in a letter of instructions to this firm, that upon his death the folio, hereunto attached, was to be delivered over to Dr. Ian Anstruther of London Hospital and Queen Anne Street whom, upon inquiry, we learned to have passed on these several years since.1 The late Dr. Anstruther was, I believe, your father.

Accordingly, upon consultation with the firm’s solicitors, and having determined you to be the only surviving son and heir of said Dr. Ian Anstruther, Cox & Company deem it will have acquitted itself of its responsibility by delivering over to you the aforementioned file.

If, sir, Cox & Company may be of any further assistance, you have only to communicate with the undersigned at the firm’s offices in Charing Cross.

I remain, sir, et cetera, et cetera...

There was a brief postscript at the bottom of the page:

I call to your particular attention that at the behest of the late Dr. Watson, included in the document attached hereunto, none of the contents of this file may be publicly revealed until the year 2000, or until such time as fifty years shall have passed from the date of his death, whichever comes later.

Inside the folder Mr. Jones found a thick sheaf of unbound manuscript paper, yellowed and somewhat brittle to the touch, the top sheet containing a dozen or so lines set down in a neat but spidery hand. Mr. Jones gasped, scarcely believing what he read. There were two names that seemed to separate themselves from the jumble of other words on the page and leap into sharp focus — two names from long ago. Both were remembered with awe, one with something approaching reverence, the other with utter horror:

Sherlock Holmes. Jack the Ripper.

EDITOR’S NOTE

The following account is based primarily on notes compiled by John H. Watson, M.D., near the end of his life, and which, as has been related, ultimately found their way into the safe of Claridge’s. The editor has tried to remain faithful to the material throughout; however, it must be appreciated there were instances when that proved to be impracticable. Because of a scarcity of detail, a conflict of dates (undoubtedly the lapses of an old man’s memory), and, as is the case in several instances, the unaccountable omission of certain established, widely known facts, it has been necessary on occasion to resort to other sources, as noted in the footnotes and bibliography. Obviously Dr. Watson never got around to organizing the notes relating to this matter in any but the most desultory fashion. It is most likely that he never intended to. Much of the information contained in the material is of such an extremely sensitive and confidential nature it is surprising that he ever reduced it to writing at all. But knowing of his reputation for discretion and great integrity and the fact that he had always respected the confidences shared with him by his friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, it must be assumed that his motives were noble, for no other assumption is acceptable. It may well be that he simply could not bear to take to the grave secrets relating to the most notorious murderer of all time. Whatever his reasons, one thing is certain: Had any of the contents of this file been revealed at the time the events occurred, or even for a good while thereafter, it would have not only ruined the reputations of several well-known, highly placed individuals, but almost certainly would have brought about the fall of the government then in power. Indeed, it may well have caused the downfall of the British monarchy.

PART ONE

“Horror ran through the land. Men spoke of it with bated breath, and women shuddered as they read the dreadful details. People afar off smelled blood, and the superstitious said that the skies were a deeper red that autumn.”

— From a contemporary account

One

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 1888

“It is not really difficult to construct a series of inferences, each dependent upon its predecessor and each simple in itself.”

— The Adventure of the Dancing Men

“A perfectly marvelous, gruesome experience,” observed Sherlock Holmes brightly as he and Watson wended their way through the crowds streaming out of the theater into the gaiety and glare of the gaslit Strand. “I cannot thank you enough for insisting that I accompany you this evening, Watson. Rarely have I been witness to a more dramatic transformation of good to evil, either onstage or off, than our American friend has so ably portrayed for us.”

He pondered for a while as they walked, his sharp profile silhouetted against the glow of light. It was the first of September, the night was warm and clinging, the myriad smells of the city an almost palpable presence. London, noisy, noisome, nattering London: aged, ageless, dignified, eccentric in her ways — seat of Empire, capital of all the world; that indomitable gray lady of drab aspect but sparkling personality — was at her very, very best and most radiant. And Holmes, ebullient and uncommonly chatty, was in a mood to match.

“I have no doubt the author was telling us,” he said after a time, “that we are all capable of such a transformation. Or, should I say transmogrification? — such a wonderful word, don’t you think? — capable of it even without the benefit of a remarkable chemical potion; that we all, each and every one of us, have the capacity for good and evil — the capability of performing both good works and ill — and precious little indeed is required to lead us down one path or the other. While hardly an original thought, it is sobering nonetheless.”2

But if he found the notion sobering, it was not for very long. He was in particularly buoyant spirits, having just the previous day brought about a successful conclusion to the amusing affair concerning Mrs. Cecil Forrester. And if his hawklike features seemed even sharper than usual, the cheekbones more pronounced, the piercing eyes the more deepset, it was due to an unusually busy period for him, one of the busiest of his career, when case seemed to follow demanding case, one on top of the other, with hardly a day between that was free from tension and strenuous mental effort. Though the pace had taken its toll insofar as his physical appearance was concerned — he was even thinner, more gaunt than ever, and his complexion a shade or two paler — it did nothing to sap his energy or weaken his powers. It was obvious to those who knew him — Watson in particular, who knew him best — that he not only thrived on the activity, but positively reveled in it, was invigorated by it. As nature abhorred a vacuum, he was fond of saying, he could not tolerate inactivity.3

Still, Watson was glad to have been able to entice him away from Baker Street for a few hours of diversion and relaxation. Left to his own devices, Holmes would have been content to remain behind, indeed would have preferred it, cloistered like a hermit amid his index books and papers and chemical paraphernalia, the violin his only diversion, cherrywood and shag his only solace.

Several theaters seemed to be emptying out at once along the Strand, and the street was rapidly filling with even greater throngs of gentlemen in crisp evening dress and fashionably gowned women, their laughter and chatter vying with the entreaties of the flower girls and the urgent cries of the newsboys working the crowd.

“‘Ave a flower for yer button’ole, guv? ‘Ave a loverly flower?”

“Murder! Another foul murder in the East End! ‘Ere, read the latest!”

“Nice button’ole, sir? Take some nice daffs ‘ome for the missus?”

Holmes and Watson elbowed their way through the crowd with increasing difficulty, conversation made impossible by the press and clamor around them.

“Here, Watson, we will never get a cab in all this. Let us make our way to Simpson’s and wait for the crowds to dissipate.”

“Capital idea, I’m famished,” Watson shot back, dodging a pinched-faced little girl with a huge flower basket crooked in her arm.

Holmes led the way, stopping momentarily to snatch up a selection of evening newspapers from grimy hands. Then the pair of them, holding on to their silk hats against the crush, forced their way through to the curb and navigated the short distance to the restaurant, gratefully entering through etched-glass doors into an oasis of potted palms and marble columns, ordered, calm, genteel murmurings, and starched white napery.4 It was not long before they were ushered to a table, despite several parties of late diners waiting to be seated; for the eminent Mr. Holmes and his companion were not unknown to the manager, Mr. Crathie, who ruled his domain with a majesty and manner the czar himself would have envied. Shortly after taking their places, they were served a light supper of smoked salmon and capers, accompanied by a frosty bottle of hock.

Conversation between the two old friends was minimal, even monosyllabic, but there was nothing awkward about it or strained, merely a comfortable absence of talk. Small talk was anathema to Holmes in any case, but the two had known each other for so long, and were so accustomed to each other’s company, the mere physical presence of the other was enough to satisfy any need for human companionship. Communication between them was all but superfluous in any case, their respective opinions on almost any subject being well known to the other. And besides, throughout most of the meal Holmes had his face buried in one or the other of his precious newspapers, punctuating the columns of type as he scanned them with assorted sniffs and grunts and other sounds of disparagement occasionally interspersed with such muttered editorial comments as “Rubbish!” “What nonsense!” and, for variety’s sake, an occasional cryptic and explosive “Hah!”

Watson, well used to Holmes’s eccentric ways, resolutely ignored him, content to occupy his time by idly observing the passing scene. The captain and waiters, on the other hand, could not ignore him: An untidy pile of discarded newspapers was piling up at his feet, and they were in somewhat of a quandary over what to do about it. Holmes, of course, was totally oblivious to it all.

“It would seem,” he said finally, laying aside the last of the journals with a final grunt of annoyance as their coffee was served — “It would seem that our friends at Scotland Yard have their work cut out for them.”

“Oh?” responded Watson with an air of disinterest. “What are they up to now?”

Holmes looked at him quizzically from across the table, an amused smile on his thin lips. “Murder! Murder most foul! Really, Watson! Surely you are not so completely unobservant that you failed to take note of the cries of the news vendors as we left the theater. The street is fairly ringing with their voices! ‘Orrible murder in Whitechapel,’” he mimicked. “‘Sco’ln’ Yard w’out a clue.’”

Watson made a face. “Well, I hadn’t noticed, actually. But surely, Holmes, neither bit of information is hardly unusual. There must be a dozen murders in that section of the city every week, and few if any are ever solved: You above all people must be aware of that. What makes this one any different?”

“If the popular press are to be believed —” He broke off in midsentence and laughed. “What a silly premise to go on, eh? Still, if there is even a shred of truth to their rather lurid accounts, this particular murder contains features that are not entirely devoid of interest. But what intrigues me more, Watson — what intrigues me infinitely more at the moment — is your astounding ability to filter from your mind even the most obvious and urgent of external stimuli. It’s almost as if you have an insulating wall around you, a magical glass curtain through which you can be seen and heard but out of which you cannot see or hear! Is this a talent you were born with, old chap, or have you cultivated it over the years? Trained yourself through arduous study and painstaking application?”

“Really, Holmes, you exaggerate,” Watson replied defensively. He was both hurt by Holmes’s sarcastic rebuke and just a little annoyed.

“Do I? Do I indeed? Well, let us try a little test, shall we? Take, for example, the couple sitting at the table to my left and slightly behind me. You’ve been eyeing the young lady avidly enough during our meal. I deduce that it is the low cut of her gown that interests you, for her facial beauty is of the kind that comes mostly from the paint pot and is not of the good, simple English variety that usually attracts your attention. What can you tell me about the couple in general?”

Watson glanced over Holmes’s shoulder. “Oh, that pretty little thing with the auburn hair — the one with the stoutish, balding chap, eh?”

“Yaas,” Holmes drawled, the single word heavy with sarcasm. He examined his fingernails. “The wealthy American couple, just come over from Paris on the boat-train without their servants. He’s in railroads, in the western regions of the United States, I believe, but has spent no little time in England. They are waiting — he, rather impatiently, anxiously — for a third party to join them, a business acquaintance, no doubt — one who is beneath their station but of no small importance to them in any event.”

Watson put down his cup with a clatter. “Really, Holmes! Really!” he sputtered. “There is no possible way you could know all that. Not even you! This time you have gone too far.”

“Have I indeed? Your problem, dear chap, as I have had occasion to remind you, is that you see but do not observe; you hear but do not listen. For a literary man, Watson — and note that I do not comment on the merit of your latest account of my little problems — for a man with the pretenses of being a writer, you are singularly unobservant. Honestly, sometimes I am close to despair.”

He removed a cigarette from his case with a flourish and paused for the waiter to light it, a mischievous glint in his eye.

Watson gave him a sidelong look. “Very well, Holmes, I will nibble at your lure. Pray explain yourself!”

Holmes threw back his head and laughed. “But it is so very simple. As I have told you often enough, one has only to take note of the basic facts. For example, a mere glance will tell you that this particular couple is not only wealthy, but extremely wealthy. Their haughty demeanor, the quality of their clothes, the young lady’s jewelry, and the gentleman’s rather large diamond ring on the little finger of his left hand would suffice to tell you that. The ring also identifies our man as American: A ‘pinky ring,’ I believe it is called. What Englishman of breeding would ever think of wearing one of those?”

Holmes drew on his cigarette and continued, the exhalation of smoke intermingling with his dissertation. “That they are recently come from Paris is equally apparent: The lady is wearing the very latest in Parisian fashion — the low decolletage is, I believe, as decidedly French as it is delightfully revealing — and the fabric of the gown is obviously quite new, stiff with newness, probably never worn before. That they arrived this very evening is not terribly difficult to ascertain. Their clothes are somewhat creased, you see. Fresh out of the steamer trunk. Obviously, their appointment at Simpson’s is of an urgent nature, otherwise they would have taken the time to have the hotel valet remove the creases before changing into the garments. That they are traveling without personal servants can be deduced by the simple fact that the gentleman’s sleeve links, while similar, are mismatched, and the lady’s hair, while freshly brushed, is not so carefully coiffed as one might expect it to be. No self-respecting manservant or lady’s maid would permit their master or mistress to go out of an evening in such a state, not if they value their positions and take pride in their calling.”

Watson sighed, a resigned expression on his face. He smoothed his mustache with his hand, a gesture of exasperation. “And the rest? How did you deduce all of that, dare I ask?”

“Oh, no great mystery, really. The man’s suit of clothes is obviously Savile Row from the cut; custom made from good English cloth. It is not new. Ergo, he has visited our blessed plot before, at least once and for a long enough stay to have at least one suit, probably three or four, made to measure.”

“Three or four? You know that with certainty, do you?”

Holmes, who was fastidious in his dress and surprisingly fashion conscious, and the possessor of an extensive wardrobe now that his success permitted it, allowed a slightly patronizing tone to color his reply.

“Formal attire would usually be a last selection; an everyday frock coat or ‘Prince Albert’ and more casual garments for traveling and for weekend country wear would customarily be the first, second, and third choices.”

Watson looked pained, but he bravely, perhaps foolishly, continued: “You said he was a railroad man. How do you come by that, eh? And your conjecture that he is waiting for an urgent appointment, a business engagement, you said — and with someone beneath his station? How do you arrive at those conclusions?” He snorted. “Admit it, Holmes: pure guesswork, plain and simple!”

“You know me better than that,” Holmes said, casually dabbing at his lips with a napkin. “I never guess.” His lips puckered in a prim smile.

“Well then?” said Watson impatiently, drumming his fingers on the table.

“It is manifestly clear that the gentleman is waiting for another individual because of his repeated glances toward the door — anxious glances which suggest that the other party is not only eagerly awaited, but of no small importance to the gentleman in question. That it is one individual and not more is supported by the obvious fact (so obvious, Watson) that the gentleman and lady are seated at a table for four, and there is only one other place setting in evidence. These conclusions are all supported by the additional observations that the man and his charming companion — his wife, I dare say, from his inattentive manner — have yet to order from the menu despite being at table for some considerable time, and the wretched fellow is well into at least his third whiskey and soda — with ice, I might add,” he said with a slight curl to the lip, “further evidence he is an American, should any be needed.”

“As for the rest —” Holmes stubbed his cigarette out and continued: “That the man has a well-stuffed leather briefcase on the chair beside him suggests an engagement of a business nature. Why else would anyone bring such an encumbrance to a late evening supper? As for the engagement being with someone beneath his station...” Holmes sighed and gave Watson a somewhat patronizing look. “Really, Watson, this is getting tiresome. Obviously, our friends over there are wealthy enough to dine at the Ritz or the Cafe Monico. Why Simpson’s, as good as it is, with its simple English fare? Hardly what a wealthy American tourist or business magnate would choose unless he had good and sufficient reason to do so — such as not wishing to appear in a highly fashionable restaurant that caters to the crème of society with someone unsuitably dressed or of a lower station.”

Watson raised his hands in a gesture of surrender. “Enough, enough; I should have known better than to doubt you. You have my most abject apologies. Now, for God’s sake let us get the bill and find our way home. I am suddenly very weary and want only my bed.”

Holmes chuckled and snapped his fingers for the waiter.

As they threaded their way toward the entrance minutes later, Watson had to step to one side to avoid colliding with a man rushing headlong into the restaurant: a short, round individual with a large mustache, who after a hurried glance around the room made directly for the table occupied by the couple in question, profuse with apologies once having arrived. He was carrying a bulky briefcase and was dressed in a sagging dark business suit, not of the best cut or material. His voice, which could be clearly heard over the hubbub of the restaurant, had a decidedly middle-class accent — lower middle class. Watson shot Holmes a sidelong glance to see if he had noticed. He need not have bothered: Holmes’s face was a mask of perfect innocence. There was just the glimmer of a smile, the mere hint of a smile on his thin lips, nothing more.

“We have a visitor, Holmes,” said Watson as their hansom clattered to a halt in front of their lodgings. There was a light in their sitting room window, the shadow of a human form in evidence.

“I am not totally surprised,” said Holmes laconically.

“You were expecting someone at this late hour?”

“No, not really. Nor am I surprised someone is here. H-Division, in all likelihood.” Without a further word of explanation he bounded from the cab, his eyes bright with anticipation, leaving Watson to settle the fare and follow.

Two

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 1888

“It has always been my habit to hide none of my methods, either from my friend Watson or from anyone who might take an intelligent interest in them.”

— Sherlock Holmes, The Reigate Squires

Mrs. Hudson was waiting for them just inside the front vestibule by the staircase landing when they entered, but Holmes rushed past her with barely a nod, bounding up the stairs two at a time.

“Yes, yes, I know, Mrs. Hudson,” he called as he ran. “Thank you, thank you kindly. No time for how-d’ya-dos.”

Watson followed at a more leisurely pace. “A good evening to you, Mrs. Hudson. Apparently we have callers. How good of you to see to their comfort. Thank you so very much indeed.”

The long-suffering Mrs. Hudson, so used to their irregular ways and the odd callers Holmes received at even odder hours, shrugged in resignation and returned to her kitchen for her nightly glass of hot milk (laced with a circumspect spoonful of whiskey) before finally retiring, she fervently hoped, for the night.

Watson, upon reaching the top of the landing, found Holmes in the front room, their common parlor, with two men, one having just arisen from the settee where he had been seated, not terribly comfortably, with teacup in hand. The other, the heavier of the two and the better dressed, had been anxiously pacing in front of the window but was now by the door, shaking hands with Holmes. It was obvious what they were, if not who they were, for while their faces were new to Watson, intuitively he was able to identify them at once: the way in which they carried themselves, their aura of authority, if not to say officiousness, was to the practiced eye identity enough — as obvious signs of their profession as actual signs around their necks would be.

“Ah,” said Watson before Holmes had a chance to make the introductions. “H-Division, I presume.”

Holmes shot him an amused glance. “No, dear fellow: CID, as it happens.” He made a gesture of presentation. “My friend and colleague, Dr. Watson, gentlemen. Watson, this is Detective Inspector Abberline and Sergeant Thicke.”5

It was the higher-ranking Abberline (for his aura of authority was just that much more in evidence) who came forward to shake hands with Watson, while the other man, Thicke, was occupied juggling his teacup, desperately looking for a place to set it down.

Abberline was a soft-spoken, portly man with a high brow and heavy whiskers who looked and sounded more like a bank manager or solicitor than a policeman. He favored Watson with a quizzical look.

“Dr. Watson is not totally incorrect,” he said. “Both Thicke and I have been temporarily assigned to H-Division on an especial duty, the very matter that brings us to you at this late hour, in point of fact.”

“Please make yourself comfortable, gentlemen,” said Holmes. “I see our Mrs. Hudson has provided you tea. May I freshen your cups? No. Well then, help yourself to cigars if you like. You will find them in the coal scuttle by the fireplace there. I won’t tempt you with a brandy or whiskey, seeing as you are still on duty.”

With a flick of the tails of his coat, Holmes plopped himself down in his favorite chair and tented his hands in front of him. “Now, pray tell me how I might be of service.”

Abberline took the proffered chair and waved away the offer of tobacco while Thicke gratefully resumed his place on the settee, teacup still balanced precariously, and peered over toward the fireplace with a bemused expression, no doubt trying to fathom why any sane individual would want to keep his cigars in a coal scuttle.6

Abberline began speaking immediately: “Good of you to see us at this late hour, Mr. Holmes. Believe me, if it were not a matter of some urgency, I would not have troubled you. Lestrade assured me that not only would you not mind the intrusion, but, to the contrary, would receive us graciously, as I have indeed found to be the case.”

“Ah, my good friend Lestrade,” said Holmes with a faint smile and noncommittal tone, concealing his somewhat low opinion of the man’s professional skills.7

“Yes, it was he who suggested that I come to you. You are known to me by reputation, of course — the assistance you have rendered to the Yard in the past is well known to us all, as is the fact that your unofficial status and your — shall we say, um, unorthodox methods — can sometimes bring about more satisfactory results than we in an official capacity can achieve.”

Though scarcely effusive with praise, this was an astounding admission coming as it did from a professional police officer, and it was one that was obviously made with some difficulty. Holmes enjoyed every word of it, but his facial expression betrayed none of his feelings. While hardly a modest man, it would have been foreign to his nature to gloat, yet he was far too forthright to indulge in false humility. He merely nodded politely, then shot a warning glance at Watson, who seemed to be having difficulty containing himself.

Abberline cleared his throat and continued: “We have a most dreadful mess on our hands at the moment, Mr. Holmes, a horrible mess, and frankly I am at a loss as to how to deal with it. I don’t mind admitting to you that as things now stand, the matter would appear to be beyond the capabilities and resources of the Metropolitan Police.”

Watson could restrain himself no longer at this admission. “What refreshing candor from a Scotland Yard man,” he said, smiling broadly. “You are to be congratulated, Inspector. You fellows usually show great reticence in admitting half as much.” He gave Holmes a wink. “Something to do with this Whitechapel business, I would wager.”

Abberline turned toward him in his chair, his expression a mixture of mild annoyance and surprise.

“Why, yes, Doctor, it is indeed the Whitechapel affair that brings us here. However did you guess?”

“Guess? Dear chap, I don’t guess. Just look at the two of you: Your boots and trouser bottoms are covered with mud — that distinctive brownish-blackish muck you will find only in the mean streets of the East End. A spattering of the stuff is even on the upper legs of your trousers and on your hats over there. You must have been crawling around in it half the night, noses to the ground, I shouldn’t wonder.” He snorted. “Obviously called out to investigate the murder of that poor woman, eh?”

Abberline and Thicke both peered at Watson with expressions bordering on admiration.

“Damn me, but that’s observant of you, Doctor!” Thicke exclaimed. “Your powers of observation are most impressive.”

Watson preened his mustache and stole a glance at Holmes. “Oh, elementary really. Nothing much to it when you have the knack.”

Holmes smiled ruefully and rendered Watson a little bow from his chair, then turned back to Abberline.

“Please continue, Inspector,” he said, his tone and look implying that he would appreciate the absence of further interruptions from Watson.

Abberline sat back, his face resuming its anxious expression. “Dr. Watson is, of course, correct. We have spent the better part of the day and evening in the Whitechapel district trying to come up with something — anything at all — that would give us a clue to this heinous crime. I tell you, Mr. Holmes, I have never come up against anything like this before. It’s the most horrible thing I have ever seen. Without doubt, the most horrible, vicious thing.”

Thicke, from his place on the settee, nodded woefully in agreement.

Holmes leaned forward in his chair with anticipation, his eyes glinting fiercely in the light of the table lamp.

“Perhaps, Inspector, I can prevail upon you to begin at the beginning,” he said softly, enunciating each word with great care. “Leave nothing out, I implore you.”

Abberline nodded, sighed deeply, and began:

“Of course it is in all the newspapers, as I am sure you have noted. The sensational press are falling all over one another in their efforts to report the events, and there is scarcely a street corner in London that isn’t emblazoned with a news vendor’s broadsheet upon which the word murder is prominently displayed.” He took a deep breath before continuing. “For a change, the newspapers are correct, I fear. The headlines are no more sensational than they deserve to be. The latest crime, Mr. Holmes, is as hideous and as dreadful as they say it is. Indeed, even more so, because the Fleet Street crowd haven’t printed the worst of it!”

Holmes raised his eyebrows but said nothing.

Abberline shook his head. “Oh, I know, I know. Violent death is no stranger to Whitechapel or to Spitalfields. As I don’t have to tell you, the Spitalfields district is populated with the very lowest of the low: the poor and the very poor and beneath them the utterly destitute — the dregs of society, as they say. Why, crime — crime in its most violent forms — is a way of life there. And life is so cheap, they’ll slit each other’s gullets for a sixpence and think nothing of it.”

Holmes nodded.

“The Evil Quarter-Mile, they call it,” Abberline continued, “and so it is. We have got eighty thousand people packed into the space of a few small acres, most of them unemployed, uneducated, diseased. Many of them surviving like foul dogs from day to day on what scraps they can find in the streets. Most of them without a shred of decency, without even a modicum of self-respect, let alone respect for others. Death is an everyday occurrence, and welcome it is to many! Hardly a day passes when somebody isn’t found floating in the Thames. We pay the river boatmen a shilling a body to bring them in. And many of them are murder victims. They’ll kill each other over a pair of shoes or a piece of bread! Or over nothing at all. Believe me, our chaps have their hands full over there.”

He paused and tugged at an ear. “But of late there has been something new, which is why we” — he nodded toward Thicke — “have been temporarily assigned to the East End, along with a dozen or so other chaps. During the last several months there have been a rash of murders that are distinctly out of the ordinary, that don’t fit the usual pattern — unusually vicious crimes, all committed with a knife, all perpetrated against women, and all of the women being ‘unfortunates,’ as they’re called — common prostitutes with hardly a copper coin to their names. In other words, Mr. Holmes, these murders don’t appear to have any motives, none at all. They appear to have been committed for the thrill of it! The sheer bloody thrill of it, if you’ll pardon my language.”

Holmes interrupted: “You speak of the murders of that Emma Smith woman last Easter Monday and, what was her name, Turner or Tabram, who was found a fortnight ago with, how many? — thirty-nine stab wounds?”

Abberline nodded his head. “Yes, those are the ones. And there have been others as well. You’ve been keeping up with things, I see.”

“It is my business to do so, Inspector,” Holmes responded.

“Yes. Well, we didn’t have a clue for either one of those homicides, not a single clue. And not a reliable witness either — one that would come forward, in any event. At first we thought some soldiers from the nearby Tower garrison or the Wellington Barracks were responsible for the Tabram murder, because the wounds appeared as if they could have been made with a bayonet. And we even made some arrests, but the two lads we had as suspects turned up with ironclad alibis and we had to let them go. And now this... this latest one.”

Abberline removed a pocket notebook from his coat and flipped through the pages, finally coming to the section he was looking for. He cleared his throat.

“At three forty-five on the morning of Friday the thirty-first of August — yesterday — Police Constable John Neil, number 97-J, of H-Division, while in the course of his normal rounds, did come upon in Buck’s Row, the body of a woman lying in the street.” Abberline put the notebook aside and continued in a normal speaking voice. “At first he thought she was just another derelict, unconscious from intoxication — God knows, a normal sight in Spitalfields. He reported he smelled the reek of gin. By the light of his bull’s-eye lantern he could see that she was lying on her back with her eyes open and staring. Her skirt was pushed up to her waist. He felt her arm and it was still warm — ‘warm as a toasted crumpet,’ he said. So he tried to get her to her feet. That’s when he saw that her throat had been cut, and the blood was still oozing out of it. Then he looked closer. The windpipe and gullet had been completely severed, cut back to the spinal cord.”

“My word,” whispered Watson.

“Funny how the mind works sometimes,” continued Abberline. “Neil told me that his first thought was ‘Well, here’s a woman who’s committed suicide!’ Can you believe that? He actually started looking around near the body for the knife she did it with. Then it came to him. She had been murdered.

“Well, as you can imagine, he started up, half expecting to find the murderer lurking in the shadows, the body being still warm and all. He was in the process of making a quick search of the immediate vicinity when he spotted the lantern of his mate who was walking the adjoining beat” — Abberline glanced in his notebook — “Police Constable Haine, number — Oh, I don’t know what it is, but he’s also assigned to H-Division. And just about the same time, another constable by the name of Misen came on the scene. It seems that two passersby on the street came upon the body just before PC Neil — a George Cross and a John Paul, both market porters on their way to work — and they had run to fetch help and came upon Misen patrolling in the next street. Neil must have come by not a minute or two later. Well, in any event, Neil called to Haine to run for the doctor. Fortunately, there’s a surgery close by, and within a quarter of an hour, no more, a Dr. Ralph Llewellyn was on the scene. He made a cursory examination of the woman, confirmed that she was indeed dead — though how she could be anything else with her throat slashed ear to ear, I don’t know — then ordered the body taken to the mortuary adjoining the local workhouse.”

“A cursory examination, you say?” asked Holmes.

“Yes, that’s right. A more thorough job was performed later at the mortuary. The light was so poor in the street, you see. Only the one gaslight on the corner, and the constables’ bull’s-eye lanterns. Don’t know how he could have done more under the circumstances.”

“So there was no search of the area for a weapon or footprints or anything at all that could have been tied to the crime?” Holmes asked.

Abberline shook his head. “No, nothing of the sort. Except, as I said, the first quick look-around that Neil conducted right after discovering the body. Not ideal conditions to find anything.”

“And when daylight came?”

Abberline looked embarrassed. “Well, of course a search was made the next morning, but nothing was found. As for footprints or suchlike, bless you, Mr. Holmes, but Buck’s Row is paved with cobbles. And the muck in the street, as Dr. Watson has so astutely observed on my boots and trousers, was by then so churned up by so many footprints, it would have been useless, quite useless, to even try to isolate the one pair that might have been of any interest to us.”

Holmes looked at him with hooded eyes. “Then the area was not cordoned off?”

“Well, not until after I reached the scene several hours later. And by then, well...”

Holmes shook his head sadly. “Please continue, Inspector.”

“Well, of course we knocked on all the doors facing Buck’s Row and questioned everybody who resides in the vicinity, but most of them were asleep, or so they say, and heard nothing. But you know those people, how suspicious they are of the official police. They’re not likely to share any information with us, even if they did know something.” His voice trailed off. He was noticeably tired and was having difficulty organizing his thoughts.

Holmes prompted him gently: “The body? It had been taken away?”

“Ah, yes. As I said, the body was ordered sent to the mortuary by Dr. Llewellyn, and it was there that a more thorough examination was in due course undertaken. And that’s when we discovered the real horror of the crime.”

Abberline paused to wipe his brow with a handkerchief taken from his sleeve. Holmes and Watson waited expectantly, not making a sound. Only the ticking of the clock could be heard, and the hiss of the gas lamp.

“It was like this,” Abberline said finally. “Dr. Llewellyn returned to his home to get a few more hours of sleep and his breakfast, while the body was stripped and prepared for autopsy. This was done by two inmates of the workhouse to which the mortuary is attached — two regulars, I might add, who have often performed the same service and are well acquainted with the correct procedures: a Robert Mann and a James Hatfield,” he said, referring once again to his notebook. “The lads earn an extra bob or two lending a hand, as it were. You know, doing the dirty work.

“It wasn’t until they were in the process of undressing the body to prepare it for the doctor that the discovery was made.”

He paused. His voice sank to a hoarse whisper. “She’d been gutted, Mr. Holmes, gutted like a fish!”

Three

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 1888

“It has long been an axiom of mine that the little things are infinitely the most important.”

— A Case of Identity

They were at the mortuary within the hour. A hastily summoned four-wheeler conveyed them through the night to the slums of the East End, although the cab’s jarvey was most reluctant at first to take them.

“Ye must be daft, or think I am!” he said from his box, shaking his head obstinately. “I’ll not be goin’ there, not at this hour of the night. ‘Tis bad enough in the daytime!”

It took a flashing of police credentials and a most impressive display of Sergeant Thicke’s official manner to change the man’s mind. It did not change his humor. He lapsed into a sullen silence for the duration of the trip, a silence frequently punctuated by venomous over-the-shoulder glances, which expressed his feelings far more eloquently than words.

The ride was not a very long one, the East End of London being separated from the West End more by birthright than distance. It is a squalid, miserable place, a place not so much where one lives as survives, but not always and never easily.

The jarvey, jaw firmly set, pulled up in front of the Whitechapel station of the underground railway, near Brady Street.

“Ye’ll ‘ave to ‘oof it from ‘ere, gents, Metropolitan P’lice or no. I’ll not be taken yer lot any further, and that’s me last word!”

Watson paid him double the fare anyway.

The mortuary, located in Old Montague Street, was but a short walk, but it is a walk into a London few respectable Londoners even knew existed. The area of the East End known as Whitechapel, though in close proximity to the lofty sacred precincts of St. Paul’s, is a low and hellish place, and the few adjoining acres called Spitalfields, which they had now entered, is the lowest level of that hell. No more than a quarter-mile square, the darkened narrow streets and alleyways of Spitalfields contained the worst of London’s slums and the very lowest form of humanity. It had been fifty years since Charles Dickens had described the district in Oliver Twist, yet little had changed for the better, and not even someone with his powers of description could prepare the unwary for the worst of it. Spitalfields was a place that penetrated the soul with feelings of repulsion and dread.8

The stench from the streets was all but overpowering, a witches’ brew of smells: the familiar odors of poverty — garbage, excrement, boiled cabbage and decay, stale beer, cheap gin and unwashed bodies — was intermixed with the stink of coal gas which permeated everything, and the gagging vapors from the slaughterhouses and tanneries and small, run-down factories that were scattered about the area.

They walked quickly, eyes to the ground, detouring when necessary around the occasional small clusters of vagrants, misshapen lumps sleeping huddled in doorways or against the building walls.

Their arrival at the mortuary was almost a welcome relief; the smells there were merely of formaldehyde and lye, strong and gagging but somehow cleansing to the nostrils. Still it was no place for those with delicate stomachs or sensibilities.9

The darkened room into which they were ushered had bare brick walls that were whitewashed once but were now coated with grime and lampblack. What illumination there was came from wall sconces that seemed to give off more smoke than the sickly light, dancing eerily on the ceiling.

The center of the room was taken up by several rectangular wooden tables, only one or two of which were bare. The others were draped with sheets of a rough material under which the lumpy shapes of cadavers reposed. Off to one side were a half dozen or so wicker baskets which at first glance in the dim light appeared to contain small bundles of dirty laundry. They contained the bodies of infants, the day’s collection.

The four of them, Holmes and Watson and the two policemen, were escorted directly and without ceremony to one of the tables located at the far end of the room. A lantern was brought and the sheet pulled back.

“She be identified as one Mary Anne Nicholls,” said a gravelly voice from the shadows, that of a mortuary worker. “Polly Nicholls, she be called, forty-two years old, mother of five, prostitute. Only known address be a doss-house at number 18 Thrawl Street.”

The four of them stood around the table as if transfixed. The face they looked down upon was that of a homely, coarse-featured woman who appeared far older than the stated forty-two years. Her eyes were open.

“Hold the light higher, please, someone!” ordered Holmes, his voice sounding unnaturally loud, even strident.

The wound at the woman’s throat grinned grotesquely in the flickering light. The blood had been wiped away so the lesion was plainly visible. The windpipe and gullet had been totally severed, cut right down to the spinal cord. On the left side of the neck, about an inch below the jaw, there was an incision almost four inches long starting at a point immediately below the ear. On the same side, but an inch below, was a second incision, which ended three inches below the right jaw. The main arteries in the throat had been completely cut through.

“What do you make of these wounds, Watson?”

Watson bent lower over the body. “From the manner in which the carotid arteries are severed, I would say it was done with an extremely sharp instrument, very sharp indeed. And see here: There are no jagged edges, no torn flesh around the throat. A very neat incision. It could have been done with a razor, or a sharp flensing knife of some sort, or even a scalpel, heaven forbid.”

“Mr. Llewellyn, the surgeon,” said Thicke, holding a lantern by Watson’s shoulder, “he thinks it could have been a cork-cutter’s blade or a shoemaker’s knife.”

“I am not all that familiar with either.” Watson shrugged.

Holmes pointed to the right side of the woman’s neck, just under the ear. “The point of entry, you think?”

“Hard to say. Perhaps.” Watson looked closer. “Yes, I think you are right. It would appear to be.”

“Now, look at the bruises here on the face, on the side of the jaw, and on the other side as well. What does that suggest to you?”

Watson took the lamp from Thicke and held it closer. “Yes, I see what you mean. They could be bruises made by fingers, perhaps — by a thumb and forefinger, as if she were held from behind with the assailant’s hand tightly over her mouth, to suppress a scream no doubt.”

“Precisely! To suppress a scream and at the same time to pull her head back and bare her throat. Excellent, Watson! And which bruise would you say was made by the thumb?”

“Well, it is impossible to say for certain, but if I had to choose, I would say the one on the right side of her face, this one here. It seems the bigger of the two.”

“Excellent again!”

“What difference could that possibly make, Mr. Holmes?” asked Inspector Abberline.

“Why, it suggests that our assailant was left-handed, Inspector. It would be quite natural for a left-handed person to grab his victim with his right so as to leave the dominant hand free with which to wield the knife.

“Oh, I see. Yes, of course.”

“That is, unless,” said Holmes, “the assailant did not accost her from behind, but — unlikely though it may be — did so facing her, in which case our man is right-handed after all.”

Abberline sighed heavily.

Holmes pulled the covering down farther, baring the woman’s torso.

“Good God!” exclaimed Watson.

Even though they had been forewarned by Abberline, the extent of the mutilations to the woman’s lower body was horrifying. Holmes and Watson had both seen many corpses over the years — Holmes had been a student of anatomy with what Watson once referred to as “an accurate but unsystematic knowledge” of the subject, and Watson, as an army surgeon, had beheld many terrible wounds — but neither of them had ever seen anything like this. Nor had the two veteran police detectives, if the tightness around their mouths was any indication.10

A deep gash, starting in the lower left part of the woman’s abdomen, ran in a jagged manner almost as far as the diaphragm. It was very, very deep, so deep that part of the intestines protruded through the tissue. There were several smaller incisions running across the abdomen, and three or four other cuts running downward on the other side.

“We identified her from the stencilings on one of her petticoats,”

Thicke said. “Lambeth Workhouse markings. The only personal articles found in her possession were a broken comb and a piece of broken looking-glass. She hadn’t a farthing to her name.”

The expression on Holmes’s face was grim, his features strained. “For God’s sake, cover her up,” he said, his voice almost a whisper.

He groped in his coat pocket for his magnifying glass and proceeded to examine the woman’s fingernails, first the right hand, then the left. After several minutes he arose from his crouched position and shook his head. “Nothing,” he said, “not a thing. One would have hoped to have found a hair or a sample of blood, even a fragment of torn skin or flesh, but there is nothing!”

He stood looking down at the woman’s body for a long moment as if his gaze alone would extract the information he sought.

Finally Abberline spoke: “Is there anything else you wish to see?”

Holmes shook his head. “No. We are finished here, I think. Let us leave this dismal place.”

It was almost dawn before Watson and Holmes returned to Baker Street. Both were tired and somewhat disheveled from their labors, the distinctive mud of Spitalfields now caking their shoes and trouser bottoms.

After leaving the mortuary, despite the lateness of the hour and lack of light, Holmes had insisted upon a visit to the scene of the crime. As anticipated, the visit was unfruitful. Holmes could do little more than ascertain where the body was first discovered, and “take the lay of the land,” as he put it. Buck’s Row, where the body had been found, was much like any of the other mean streets of Spitalfields, a narrow, gloomy passageway lined with rows of ramshackle tenements smelling of rotting garbage. One end of the alley let out into Baker’s Row, the other into Brady Street.

“If it were me,” said Thicke, “I would ‘ave made straightaway for Brady Street and thence for the underground station at Whitechapel Road. Easy to get lost in the crowd there.”

“You have as good a chance of being right as wrong,” responded Holmes, “inasmuch as there were only two ways our man could have gone.”

“Of course we questioned everyone who lives in the alley,” Abberline said. “No one saw or heard anything, which is what you might expect them to say — to us, in any event. Although Thicke here is well known by the locals, and is probably trusted by them more than most of us. They would talk to him if to anyone.”

“And none of them heard anything?” asked Watson.

“No,” replied Thicke, shaking his head. “The closest would have been Mrs. Green, who lives down there just a few doors away, and she said she didn’t ‘ear a thing, not a blessed thing, even though she was awake. Couldn’t sleep, she said. I know ‘er; I think she’d tell me if she knew something. Mrs. Emma Green is ‘er name, a decent sort really.”

Holmes shrugged. “Me for my bed, gentlemen. There is nothing to be learned here.”

Abberline would not leave it at that, however. “Do you not have any thoughts at all, Mr. Holmes? Or suggestions?”

“Only one, I’m afraid. Wait for the next murder.”

Watson and the two policemen stared at him.

“Oh, there will be another one, have no doubt. Have no doubt whatsoever.”