Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

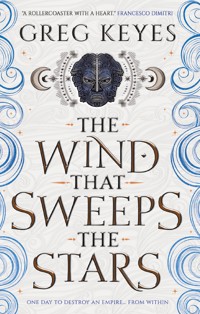

A taut high fantasy as an assassin must destroy an empire from within, eliminating wizards, their demons, and even the emperor. For the lives—for the very souls—of her people, she must succeed within a single day, or her homeland will be destroyed. ALONE AGAINST AN EMPIRE. When Yash of Zeltah arrives in the fortress city of Honaq she is greeted as a barbarian, a simple pawn. Her marriage to prince Chej has been arranged, they say, to avert war. Yet she knows the truth, for the armies already ravage the land. A skilled and deadly assassin, there is more to Yash than any might suspect. Before another day can pass, she must defeat the masters of the nine towers—the plagues, magics, and monsters they control, the soldiers they command. Without raising an alarm, she must kill all who oppose her—even the immortal emperor. The lives and souls of Zeltah, the people and the land upon which they live, all depend on it.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 509

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One: Dzhesq The Needle

Chapter Two: Yash

Chapter Three: Chej

Chapter Four: Hsij The Yellow

Chapter Five: Deng’jah

Chapter Six: The Nełts’eeyi

Chapter Seven: Xarim Ruesp

Chapter Eight: Hana

Chapter Nine: Zu The Bright

Chapter Ten: Hsheng

Chapter Eleven: Xuehehs The Obsidian

Chapter Twelve: Tchiił

Chapter Thirteen: Plots

Chapter Fourteen: The Grey World

Chapter Fifteen: The Naheeyiye

Chapter Sixteen: Qaxh The Coral

Chapter Seventeen: The New Bargain

Chapter Eighteen: Sha The Sharp Horn

Chapter Nineteen: The Place Where they Changed

Chapter Twenty: Ghosts

Chapter Twenty-One: The Beast

Chapter Twenty-Two: Chej’s Courtyard

Chapter Twenty-Three: The Sewer

Chapter Twenty-Four: Sil The Examiner

Chapter Twenty-Five: Earth Center Tower

Chapter Twenty-Six: Hguesyaj

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Father and Daughter

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Ruzuyer

Chapter Twenty-Nine: The Rizua

Chapter Thirty: Yir The Pinion

Chapter Thirty-One: The Emperor’s Monster

Chapter Thirty-Two: The Tower of the Birds

Chapter Thirty-Three: Among The Flowers

Chapter Thirty-Four: The Giant of Stone and Flowers

Chapter Thirty-Five: The Painting

Chapter Thirty-Six: In The Skull

Chapter Thirty-Seven: A Mother’s Gift

Chapter Thirty-Eight: Zełtah

Chapter Thirty-Nine: Minad’ha’wi

Chapter Forty: Teqeqande (The Dawns to Come—The Future)

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise forThe Wind that Sweeps the Stars

“Greg Keyes’ mastery of language and character is second to none.”

Elizabeth Bear, author of Ancestral Night

“A fast and furious book, written by a modern-days Robert E. Howard. It is a rollercoaster with a heart: it grips you from the go and leads you on a neck-breaking journey of adventure, misdirection, and wild magic, without ever losing sight of the characters’ soul. I had so much fun I already want to start it again.”

Francesco Dimitri, author of The Book of Hidden Things and Never the Wind

“An intricately built world with a deep sense of history, and the feeling of a life that extends beyond the page.”

A.C. Wise, author of Wendy, Darling and Hooked

“A fascinating book—adroitly leaping between spiritual revelation to Die Hard in the Wizard’s Tower.”

Gareth Hanrahan, author of the Black Iron Legacy Series

“Teems with magic, spirits, and wonderment in a seething mass as vital as the arc of Yash’s blade.”

Anna Stephens, author of the Godblind trilogy

“Captivating, beautiful and gripping.”

Anna Smith Spark, author of The Court of Broken Knives

“Action-packed, fast-paced, built on a rich tapestry of history and characters, The Wind that Sweeps the Stars is fantastic fantasy storytelling.”

Edward Cox, author of The Relic Guild

“An intriguing fantasy world that draws you in, an exciting mission that builds and builds to a devastating climax. Recommended reading for anyone who likes their sword-and-sorcery unconventional and constantly surprising.”

Dr Fiona Moore, author of Management Lessons from Game of Thrones

Also by Greg Keyes

Kingdoms of Thorn and Bone

The Briar King

The Charnel Prince

The Blood Knight

The Born Queen

The Age of Unreason

Newton’s Cannon

A Calculus of Angels

Empire of Unreason

The Shadows of God

The High and Faraway

The Reign of the Departed

The Kingdoms of the Cursed

The Realm of the Deathless

The Basilisk Throne

Interstellar

Godzilla: King of Monsters

Godzilla vs. Kong

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes: Firestorm

War for the Planet of the Apes: Revelations

Marvel’s Avengers: The Extinction Key

Pacific Rim

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Wind That Sweeps the Stars

Print edition ISBN: 9781789095500

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789095517

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: August 2024

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Greg Keyes asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2024 Greg Keyes. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Rosemary,Or Rose by any other name.

CHAPTER ONE

DZHESQ THE NEEDLE

DZHESQ, MASTER of the Blue Needle Tower, murdered a slave and read the portents in the dimming of her eyes. He traced signs of pulverized bone around the corpse, burned the resin of a plant from another world, and called upon his xual to aid him. The xual answered, and the scent of wildflowers filled the room. Demons of pestilence and despair drifted out of the smoke from the burning pitch. Dzhesq the Needle set them on a north-blowing wind. Afterwards, he washed his hands and groomed himself, admiring his beautiful, tapered face and dark eyes in a mirror before descending from his tower to visit the Princess Yash of Zełtah.

“I’m afraid I have some bad news,” Dzhesq told Princess Yash.

She had been standing near the window when he arrived, staring into the distance, probably pining for her barbarous homeland. Now her dull black eyes were fixed on him where he stood in the doorway to her chambers. She had changed out of her colorful and elaborate wedding dress and now wore a tan silukur robe. The garment hung from her broad, bony shoulders, emphasizing the deficits of her wiry, unlovely figure. She looked like a starved, mangy dog that had been shoved into expensive cloth.

“I’m so happy for you,” she said.

“I’m sorry,” Dzhesq said, unsure what she meant. “You’re happy for me?”

She nodded and made a grimace that was probably meant to be a smile. Her eyes were too far apart, and her mouth was so wide she reminded him of a frog.

“People say they hate to bring bad news,” she said. “But almost everyone rushes to do it, don’t they? To be the first to tell it. To see the reaction—the frown, the sadness, the fear. The tears. When you bring bad news, you can see all of that. You can be the one to make that happen. But there’s no guilt—you can’t be blamed, can you? It’s not you making them cry, it’s the news. You’re providing a service. They’ll be grateful to you. Maybe they’ll even be a little sad for you that you’re the one that must tell them.” The ends of her mouth turned further up, so that even on her unfortunate face there was now no mistaking the attempted smile. “So, I’m happy for you, that you have bad news to tell me. I hope you enjoy it. Does it concern my husband? I was expecting him by now.”

Self-awareness was important, Dzhesq knew, so he paused to reflect that he had never wanted to hit anyone so much in his life. No, not hit her. He wanted to unsheathe the demon-bone knife at his belt and stab it through her windpipe, end her crude attempt to speak his language. And her insolence. She was making fun of him. No one did that. No one spoke to him like that. Not for many years, and for good reason.

Least of all an ugly little barbarian.

It was all made worse, of course, by the fact that at present he couldn’t hit her or stab her. The Emperor wanted her alive. But when the day came that she was of no further use to the Empire, things would be different. That thought soothed him. It got him through the moment.

“No,” he replied, evenly. “Your husband is not yet done with his purifications. He will soon be ready for you. You need not worry on that account.”

“I’m not worried in the slightest,” she said.

It was the way she said it that got his attention. As if she was asserting herself.

“I take it that this marriage was not of your choosing?” he asked.

“I would not have chosen it, no,” she said.

“You thought you could do better than Prince Chej? Or marry for love, perhaps, rather than for reasons of state?”

“I didn’t say any of that,” the girl replied. “You asked a question. I gave you an honest answer. I don’t want to be married to Chej. I don’t want to be here, in this place.”

“But you agreed to the match, did you not? Your family said you did. You said so at the wedding. You seem to value honesty. Were you being dishonest, then?”

She cocked one eyebrow and took a step away from the window toward him.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “We were not introduced. Who are you?”

“I am Lord Dzhesq nXar Hsa, Master of the Blue Needle Tower. By custom you may address me as Master Needle or Master Dzhesq the Needle.”

“Oh,” she said. “One of the tower masters, yes? A, um, dj’ende? I don’t know your word.”

He knew the word dj’ende. In her language it meant “evil spirit.”

“You don’t know your own words,” Dzhesq retorted. “Much less mine. In your language I would be called a duyenen. In mine, the title is zuen. A holy man.”

“You practice sorcery,” she said, wriggling her fingers at him. “You send plagues and demons to destroy your enemies, yes?”

“Among other things,” he agreed.

She shrugged. “Then we agree on what you are. The word we use does not really matter, does it?” She smiled again and nodded, as if they were friends sharing a little joke. “But,” she went on, “now that we are introduced, I am pleased to answer your question. Of course I agreed to marry Chej. Our kingdom is small. Yours is large. If our countries had not been joined by marriage, you would have joined them with your army. So here I am.”

Dzhesq nodded. He was starting to feel better now.

“So, you are a dutiful woman,” he said. “That is good.”

She shrugged. “You said you had bad news?”

“Yes,” he said. “I’m afraid there has been a change in your accommodations. You must accompany me to the Blue Needle Tower. Rooms have been made ready for you there.”

“That isn’t news, bad or good,” Yash said. “It makes no difference to me where I stay. But you will have to show me. This place is altogether confusing.”

“A bit grander than your little pile of rocks back home?” he asked, stepping aside and ushering her toward the door.

“Yes!” she said. “It’s very big, with so many rooms. And so many towers! It looks like a mountain covered in yellow pines from a distance. And every tower has a master, like you, yes? I imagine you must be the grandest master of them all.”

“I am highly ranked,” he said. In fact, of the nine tower masters, he was reckoned third in power and prestige. “The Emperor is most highly ranked, of course.”

“Oh yes, of course,” she said. “I meant after him.”

Let her believe what she wanted. What the awful, despicable creature thought was less to him than what a red ant could carry.

They wound their way through the twisting corridors of the fortress. The barbarian princess prattled the whole way, asking questions about everything she saw. “What’s through there? How does this curved roof stay up by itself? Is that carving a toad or a bug of some kind?” When they reached the polished stone floor of the lowest court of the Blue Needle Tower, her eyes widened comically.

“So many warriors!” she said.

Dzhesq glanced at the twelve guards in their lacquered leather cuirasses watching them enter the tower.

“Sentries,” he replied. “To keep you safe.”

“Safe?” she said.

He nodded.

Once they began up the spiral staircase, Princess Yash became mercifully less verbose, saying only, “It’s awfully tall,” and, “Are we going to the very top?”

He answered yes to both questions.

When they reached the uppermost floor and stepped into the chamber there, she nodded.

“Cozy,” she said. “I like it.”

It consisted of only three rooms and was less than half the size of the suite she’d had downstairs.

“More like what you’re used to,” he said.

“Yes, of course,” she replied. She went to the window. “The view is fantastic, too. I can see the Tsewe Zeł Mountains.”

“Yes, we’re quite high here.”

“Why the change in rooms?” she wondered.

“That’s the bad news,” he said. “You see? I did not hasten to tell it to you, as you predicted. The bad news is that a short time after your wedding concluded, the Emperor ordered the invasion of your kingdom. You are now a valuable hostage, and we cannot run the risk of some sort of misguided rescue attempt. You will be quite safe here, and in a matter of days, when the war is over, you will no doubt be allowed to take up residence in your husband’s quarters.”

He paused to enjoy her look of perplexed horror even though it wasn’t exactly what he had been imagining. If he didn’t know better, he might think she didn’t look shocked at all. Maybe more… relieved?

“Let me be sure I understand,” the princess said. “The terms of my marriage included the provision that the Empire would not make war on my country?”

“Yes.”

“But your emperor has nevertheless sent an invading army there.”

“Also yes.”

“Well,” she said, nodding. She looked around the room, then went over to the padded mattress on the floor. She knelt and picked up a small soapstone incense bowl, turning it in her hands.

“You will be my keeper, Master Dzhesq the Needle?” she asked. “That is why you brought me to your tower?”

“If you want to look at it that way,” he said.

She nodded again and started to set the little fist-sized bowl down.

Then she moved. Very quickly.

The stone bowl hit him in the throat before he realized what had happened. He stumbled back, clutching at his windpipe as she ran toward him. He couldn’t breathe, his scalp was tingling with alarm, and he didn’t understand what was going on. He put his hands out toward her and tried to command her to stop, but he couldn’t get the words out.

She drove her small fist into him, just below his breastbone. It felt like it was made of granite; all the air went out of him, and he fell back, black spots filling his vision. The next thing he knew she was behind him, her arm wrapped around his neck.

She’s attacking me, he realized. But that was ridiculous. He was twice her size. He could beat her to death with one hand. But more than that, he was a tower master, with all the power that entailed.

With no voice, he couldn’t call his xual—it was too far way. But there was help nearer, so he didn’t have to speak the word aloud, only to concentrate on it, form it in his head. Even though at this moment that was harder than it should be, especially for someone of his power.

Neheshhish, he finally managed.

Then the chuaxhi sewn inside of Dzhesq’s skin burst forth from the tattooed line on his sternum, looking at first like a stream of white smoke but quickly forming into a bent, lizard-like figure armored in alabaster scales standing half again as tall as a man.

He was relieved, but he still couldn’t breathe. Everything went dark.

But then the light returned; his ears were ringing, and his lungs were filled again. Now he could smell the burnt-air scent of the chuaxhi. It was across the room, slashing at Princess Yash with talons as long and sharp as knives. Dzhesq knew he was going to get in trouble for this—the chuaxhi was going to shred the ugly little girl, and the Emperor wanted her alive. But there was nothing he could do now. This was her fault, as anyone could see.

As he watched, Yash ducked and dodged the chuaxhi’s attack and slammed her hand into its belly; white smoke sprayed out. How was that possible? The chuaxhi had skin harder than quartz. What could—

Then he saw. She had a knife, his knife, whetted from a sliver of demon bone from the White Brilliant.

He realized the chuaxhi was leaking smoke from at least five holes in its armored hide.

He pushed himself to standing as Yash cut one of his protector’s feet off. As the chuaxhi fell back, Dzhesq tackled Yash from behind, intent on knocking her to the stone floor, but she pivoted and twisted so they fell side by side. Her small frame was hideously strong, as if knotted together from sinew. She grabbed his wrist, bent it painfully and banged it against the floor. He heard one or both of the bones in it snap, the pain traveling like lightning up his arm. Then she was up and away from him again, returning her attention to the chuaxhi.

Dzhesq fought back to his feet, clutching his broken wrist with his good hand. He ran. At first he wasn’t sure where he was going —just away—but then he knew. His summoning room, where his power was greatest, where his xual waited to protect him. Once there, she would face the full measure of his might, and none of this would matter. No one would know.

He reached the stairs and began stumbling down. His breath wheezed in through his swollen throat. He tried to scream for help, but still no sound came out. But he was almost to the next landing. Looking back, he didn’t see her. She was still fighting the chuaxhi. Maybe it had killed her, even. But he wasn’t taking that chance. He took another step, and another. He could see the door to his rooms.

Something hit him in the small of the back, hard. He fell forward on the stairs, trying to catch himself with his broken hand before his face crushed against the stone. He was fine, he thought. This was stupid. This was not happening to him.

He realized he had tumbled the rest of the way down the stairs and was on the landing. The door to his room was just to his left. Trying to rise again, he saw Yash was in front of him now, her eyes as cold and sharp as obsidian chips.

“Stop it,” he managed to say, in a hoarse voice just above a whisper. “You are nothing. No one. I am Dzhesq nXar Hsa.”

“I have some bad news for you,” she said.

CHAPTER TWO

YASH

TSAYE (IN ANCIENT TIMES)

WE DON’Tknow how the world that contains all other worlds began. That is a mystery it holds to itself. But we know there are many worlds. Some are far away from the one we call home. Some are as near as the outside of your skin is to the blood in your veins. Our people traveled through many worlds before they reached this one, where we made our true home. During that journey we changed, many times.

DII JIN (NOW, TODAY, THE PRESENT)

YASH WITHDREW the knife from the base of Dzhesq the Needle’s skull and sat on the stairs for a moment to catch her breath. She touched the sorcerer’s neck to feel whether his blood was moving. It wasn’t.

The dead sorcerer lay on a landing five or six strides wide, beyond which the stairs continued down, curving along the outside wall of the tower. All was made of polished dark-blue granite with streaks and patches of white, like clouds swirled in an evening sky.

Her gaze came to where a pool of Master Needle’s blood was still spreading.

She had killed many things in her life. Animals. Monsters. But this was the first human being she had slain. Or did a sorcerer count as a human being? Yes. This was a new thing for her.

She hadn’t known what she would feel at this moment. She still didn’t, and it didn’t matter. The tower master was her first. More enemies might already be on their way.

She closed her eyes and listened. To her relief, the stairwell was quiet. But for how long? There was no telling. She couldn’t take the body back to her room; there was no place to hide it. If she shoved it out the window, someone might see it falling or hear it land. But there were other rooms.

She rose, took hold of the corpse by the hair and began dragging it across the blue stone.

She had noticed the door on the way up. Most of the doorways she had seen inside of the tower were simply open, but this one was closed by a slab of dark wood. It hung on metal pins fitted into the stone wall. A loop of copper halfway up suggested it pulled open.

She took hold of the handle and yanked.

It was heavy, so she had to release Needle’s hair and brace one foot against the wall to start it opening. But when it had cracked about the span of her arm, someone began pushing it from the other side. She jerked her feet up and clung to the copper as the door swung wider.

She couldn’t see who it was, but they made a grunting sound. Whoever it was could surely see Needle’s corpse lying on the landing. She pulled the knife out and dropped quietly to the floor.

Then someone stepped out and toward the dead sorcerer.

He was big, taller than any human, but he looked more like a man than the thing that had come out of Needle’s chest. But he wasn’t. His skin was roughly pebbled and grey. His long hair was coarse, each strand of it as thick as her little finger. He wasn’t wearing any clothes.

She leapt toward his unprotected back, but the being spun around far faster than she had imagined he could and caught her right arm with his huge hand. She thrust the blade at him with her left, but his other hand clamped on her wrist. She swung up, twisted, and kicked him in the chest with both feet. That surprised him and broke the hold on her right arm. He growled and hurled her through the door. She skidded across polished stone and then rolled back to her feet. He bent and picked up a heavy wooden club bristling with flint spikes from where it lay on the floor. He took a step toward her. But he paused, his eyes cutting back to the landing.

“Wait,” the giant said. “You killed him.”

“Yes,” she replied.

“Good. But why?”

“Does it matter?”

“No,” the giant replied. “But I’m pleased. I did not like him.”

“I didn’t like him, either,” Yash said. “Maybe you and I don’t have to fight.”

“Maybe,” the giant said. “Who are you?”

“I am Yash,” she said. “I—”

But then he jumped toward her. She saw it coming; he had been inching forward as they spoke. He was big and fast and very strong. She had been lucky to get away from him when he caught her before. She couldn’t let that happen again; he probably wouldn’t make the same mistake twice.

He whipped the club toward her head. She dodged, barely, then she ducked under his arm and stabbed him in the armpit. To her surprise, she felt resistance; whatever he was, he had bone there, where a normal person did not. The blade went in anyway and came right back out. She skittered past his ribs, hoping to get to his back, but he managed to turn with her, swinging a backhand at her head. She quickly ducked beneath the blow again and sliced open his inner thigh. Blue-white blood sprayed out; she smelled wildflowers.

He stumbled and then lurched at her.

She weaved through the large, cluttered room. He crashed after her. She ran under a table, toward an open window beyond. Something whooshed by her head and shattered against the wall near the opening. She turned around in time to see him flip the table toward her. She jumped into the window frame and teetered there on the sill, which was only barely wider than her footspan, fighting to keep her footing as the table slammed into the wall, briefly blocking the window before falling back into the room. She dove back inside, barely evading the next wicked swing of his club, and sprinted back toward the door with him panting at her back. Getting slower. The pale blood was everywhere now.

“You’re waiting for me to bleed to death,” he growled.

“You didn’t give me much choice,” she said.

“I don’t have any choice,” he said. “Even dead, his command on me remains. I must kill you.”

“I’m sorry for that.”

He charged but was a lot slower this time. She feigned backing up but then stepped quickly to the side and lunged to meet him, making him badly misjudge his swing. She shoved the knife through the ribs where his heart should be. The blade lodged there, and rather than sticking with it—easily within the grasp of his monstrous arms—she let go and spun around, ready for his next attack.

His back was still to her. Wheezing, he sank slowly to his knees and toppled forward.

She watched for a few heartbeats to make certain he wasn’t trying to fool her. Then, giving the giant’s body a wide berth, she went back to the door, dragged Dzhesq’s body inside, and closed it behind her.

The giant still hadn’t moved, and the huge pool of blood he now lay in was convincing evidence that he wouldn’t. Still wary, she examined the room a little more closely. It was almost round, which meant it probably took up this entire floor of the tower. There were two large tables and dozens of smaller ones, racks of shelves filled with scrolls, pots, urns, and cauldrons, three of which had been toppled and broken during their fight, spilling ochre, green, and dark purple powders on the floor. The giant had thrown one of the big tables at her, and it lay upended near the window. On the table that was still upright, bits of bone, metal, shell, and stones of various colors and sizes had been sorted into piles, but she couldn’t discern what categories they had been grouped into. Near the window a pedestal supported a large incense bowl, this one blue-green and carved from precious dedłiji stone.

A large wooden case contained an assortment of tools—knives with blades of bronze, bone, and obsidian; hammers with heads of progressively larger sizes, the largest a little bigger than her closed fist; and an axe with a coppery-looking blade. A large cabinet contained clothing, none of which would fit her.

When she ventured to the side of the room farthest from the entrance, she discovered a corpse; the clutter had prevented her from seeing it earlier.

There, beneath another window, the floor had been traced with strange symbols. Some looked like writing, others appeared to be stylized animals. They formed a double-armed spiral. It looked to her like four of the symbols indicated the cardinal directions.

A woman lay in the middle of the markings. She was probably around thirty, dressed in a dark yellow shift. Her hands and feet had been bound with rawhide strips, and her mouth and nose were covered with what Yash at first took for some kind of paste. Her dead gaze was fixed somewhere between the floor and the ceiling. Her skin had a blueish tinge.

She had been smothered to death slowly. Whatever Needle had put in her mouth and nose had hardened into a rubbery substance while she was still trying to breathe.

It was one of her own people, a woman of Zełtah. Yash didn’t know her name, but by the arrangement of piercings in her ears she guessed her to be a white-spruce woman, probably from Tsecheen.

She wished there was something she could do for her, but there wasn’t. Whatever the sorcerer had done to her, the woman’s soul was either consumed or long gone. Her body was just that: a corpse. Her people didn’t bother much about those.

“He is dead,” she whispered, in case something remained that could hear her. “If that can be of comfort.”

It was all she could do, and she had to move on. But a pitch-knot of anger had formed inside of her, a splinter, but one that could become a white-hot fire, given the chance.

I don’t need you, she told the pitch-knot. I will do this without you. She took a long, slow breath, and the splinter flowed out of her. She took one more to be sure.

Now certain the giant was dead, she rolled him over. It wasn’t easy, but it was the only way to get the knife back. Then she pried the giant’s own weapon from his fingers and crushed Needle’s chest with it, placing a dagger from the case in the sorcerer’s hand and returning the giant’s club to him, folding his thick dead fingers around the handle. Now it looked like the two had killed each other. How long that would fool anyone—if it fooled anyone at all—she did not know. But from now until she was finished, every pulse of the heart counted. If the deception gave her a dozen or thousands, it was still worth the effort.

But as valuable as time was, there was something more to do before she left.

She knelt by the dead giant and touched two fingers to his blood. Then she closed her eyes and tried to clear her mind.

Shame, bondage, and misery met her touch, surging from the corpse up through her fingers and quickly spreading throughout her body. She felt ill. She struggled not to vomit. She clenched her teeth as tears started in her eyes.

“I am sorry, my foe,” she whispered.

I am sorry.

But we were fated to fight

And one to die

I am sorry, my foe

I am sorry I do not know your name

Or the place that gave you life

And meaning.

Who are your kin?

Where is your place?

I want to know.

Slowly, the darkness beneath her eyelids brightened, as if a dense fog was dispersing. She began to make something out. The smell of flowers grew stronger until she saw them in a mountain prairie: a field of yellow, white, crimson, and violet surrounded by the pale trunks and green spring leaves of aspens.

“I see you now, my former foe,” she sang softly.

T’chehswatah

In the fields of flowers

Among the Aspens

In winter wears a white mantle

Waiting for the spring

It is spring for you now

Go there, my brother

Go there, my sister

Be among them once more.

Her vision grew clearer. All of the trees and flowers bent in the same direction as a wind came up. Then all was still.

Thank you, the wind whispered.

“You are welcome,” she replied. Then she stood and went to the window. She looked off toward the mountains.

“Shechu,” she murmured.

One has gone now, my grandmother

One has returned home

One of the naheeyiye

To T’chehswatah

Perhaps they left

A way in

A way in here

Into Dj’eendetah, Among the Monsters

Into Qen Dj’eende, The Abode of Monsters

I could use some help

Shechu

My grandmother.

She waited, but no answer came. And she could wait no longer, not in this room.

She hurried back up the stairs to her new quarters and stripped off the robe, now soaked in blue-white blood. A quick search of the suite turned up a low table with a pile of clothes on it that seemed meant for her. She found another robe, this one dark blue. She shoved the bloody one under her bed and looked over the rest of the room. The chuaxhi was now gone without a trace, evaporated back into steam, returned to its alien realm. To her eye, nothing looked out of place.

The adjacent room had a washbasin and some cloth; she wiped her face and arms until they looked pretty clean, squeezed the blue tinted water from the rag out the window, threw the rag back by the basin, then donned the robe.

Then she went back to the window and leaned out.

She could see half of the fortress, and beyond that, part of Honaq city: thousands of houses built on the hills around the river. She had seen it upon arriving and thought it both amazing and repellant. Far too many people crowded into one place for her taste, too much smoke from too many fires. Even so, Honaq had a certain beauty. Toward the center, where the fortress she now occupied stood, it was orderly, a place designed by clever people who liked straight lines and perfectly round circles. But as it spread, it became more like a living place, more accountable to the contours of the river and landscape than to human imagination. The yellow and brown swaths of stone and mud-brick buildings were striated with vivid green gardens and flood-marsh, expanding at the city edges to join the verdant fields filling the rest of the valley. Boats like colorful water-beetles cut ripples in the surface of the river and tree-lined canals. She was sure that, given time, she could find more beauty in Honaq.

Right now, however, the city was not her concern. The fortress was.

The fortress was surrounded by two circular walls, the innermost of which had eight towers along its circumference, with a ninth, larger tower in the very center of the structure. From this window of the Blue Needle Tower she could see four others.

The closest was the color of pine pollen: possibly the Yellow Bone Tower. It had a window facing her about two lengths of her body lower and another farther down. Just at the edge of the distance she could jump.

She heard something behind her and turned.

A big man—tall, wide-shouldered, with a rounded, soft face and substantial nose—stood in the doorway.

Chej, her husband.

CHAPTER THREE

CHEJ

Q’ANID (IN THE RECENT PAST)

EIGHT DAYS EARLIER

PRINCE CHEJ met the woman who was soon to be his bride in a fortress on a mountain ridge in the barbarian kingdom of Zełtah, north and west of Honaq city, and seven days’ travel beyond the boundaries of the Empire. They were introduced in a courtyard beneath the shade of a cottonwood tree and seated on stone benches facing one another, surrounded by their respective entourages. The meeting was awkward, made more so by the need for translators, and he did not leave the meeting with warm feelings about his upcoming wedding.

Not that he had expected to. His fondest hope had been never to marry at all, and as his age had trickled through his twenties and into his early thirties, that had begun to seem possible. He was not, after all, an important prince. That was not his opinion, but a plain fact, and one that had been made clear to him since birth. He had been mostly ignored by the court, but at a certain point he had stopped feeling sorry for himself and begun to realize that it could be a blessing. The essence of neglect was that no one was watching you. And if no one was watching you? Well, that was at least similar to freedom.

Now, suddenly, people were paying attention to him again, and he didn’t like it.

The meeting with his bride-to-be was over, and the whole thing a blurry, rapidly fading memory. His advisors met with her advisors, his family with hers, and he managed to slip off with his bodyguards and return to his encampment on the high ground just below the fortress. He dug a bottle of blackberry wine from his things and took it out to the edge of the bluff where his escort had built him a fire. The wood burned with a scent of juniper, almost like incense. He sat, drinking, looking down at the many dozens of campfires below. The barbarians were planning some sort of ceremony to see their princess off. He was told that they had come from all over the mountains and high plains, and now their tents were spread out beneath the fortress and their fires were like a night sky fallen to earth.

He had traveled before. A brief stint in the army had taken him to some of the downstream kingdoms, but, on reflection, those were all very like Honaq, at least compared to this place. The “fortress” was rudimentary, a structure carved from the living rock of the ridge, built up here and there with closely fitted stones. From a distance, it looked almost like it was just part of the cliffs. There was a town of sorts situated at the bottom of the ridge, a collection of round huts of various sizes, and some fields arranged near the spring that flowed out there. But most of the people of Zełtah, he had gathered, didn’t live in towns or cities, but were scattered over the landscape with their herds. He had found that land forbidding, at first—harsh and arid, with none of the lush vegetation of his valley home. But in the days coming here, he had come to appreciate the spare red cliffs and the distant mountains that bordered every horizon and the huge sky above it all. Each sunrise and sunset was spectacular beyond his ability to describe them. It was as if the sky invented new colors each day.

She arrived at his fire without him knowing it, although his men had noticed and dragged a log over for her. She sat down on it and nodded at him. At first he didn’t recognize her. Back in the courtyard, she had seemed tiny, almost like a child. Standing facing each other, her head had only come up to his chest. Out here, in the night, she seemed larger, even though he knew she couldn’t be.

“Princess,” he said. He tried to remember the four or five words of her language he had learned on the trip here.

“Daxudzhue,” she said.

“Oh, you know how to say hello in my language,” he said. He knew that shouldn’t be embarrassing. It was expected. But he felt at a disadvantage.

“Ah, huchun,” he attempted, in hers.

“Hee’echuun,” she corrected. But she looked pleased. “Nice of you to try,” she said.

“You—you speak my language?” he asked.

“Yes,” she said. “Of course. You in the Empire are my cousins, are you not? Or so they say. And an important fact in our lives. In my life now. How could I live in a place where I couldn’t understand anyone?”

“Yes,” he said. “I can see that. Of course, I can see that. But earlier, at our meeting…”

“It was best to let the interpreters talk,” she said. “It was all so formal. But I thought now we should really meet.”

She seemed earnest and younger than the twenty-seven winters her family claimed she had.

“Do you want some wine?” he asked.

“No, thank you.”

He nodded, trying to think of what to say. He studied her for a moment.

“So, we are to be married,” he ventured, after a moment.

She smiled. “I see you aren’t all that happy about it, either,” she said.

It was so unexpected he choked on his wine. She laughed as he wheezed it out of his nose.

“What’s wrong?” she asked.

“You were honest,” he said. “I wasn’t expecting that.”

“That’s too bad,” she said. “Everyone deserves honesty. I hope I haven’t offended you.”

“Do you?”

“Of course. We have to live with each other, don’t we? Make children together?”

He wagged a finger at her. “You’re trying to make the best of this,” he said. “How dare you.”

She smiled. Her face was nearly round, and her smile was huge. Her eyes flickered like stars in the flame.

“I will be in a place unknown to me,” she said. “I need at least one friend, don’t I? It might as well be my husband.”

“I think I can manage that,” he said. He took another drink. The wine was starting to warm him up inside, loosen him. “Look,” he said. “We needn’t take any of this too seriously. We can put on appearances, and all of that. But I want you to understand, I don’t expect anything from you that you aren’t willing to do.”

“You mean like sexing?” she said.

“Having sex,” he corrected. “But yes, that, among other things.”

She shrugged. “That’s nice of you. And I fear you might crush me if we did that.”

He froze for a moment, remembering someone else who had said exactly that.

She must have noticed.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I didn’t mean to upset you. It was a joke. You’re a large man, but there’s nothing wrong with that. I know there are ways to do sex without me getting hurt. If we must make babies.”

He examined her face, trying to see if she was still joking.

“Do you want babies?” he finally asked.

“Not anytime soon,” she said. “Maybe not ever.”

“We agree on that,” he said.

She nodded. “But your family? What will they think?”

“Believe me, whether I have heirs is of no real importance to anyone.”

“How can that be?” she asked. “The marriage is an alliance, isn’t it? Between the Empire and Zełtah?”

He nodded. “Yes. But it’s complicated. I guess. To be honest, I’m not sure why they chose me to marry you.”

She nodded. Then she looked out at the campfires below. “My people,” she said, pointing with her lips. “Some traveled twenty days to be here.”

“I heard about that,” he said. “Your people do you proud.”

“And I will return the favor.” She seemed to hesitate over something then reached her hand out toward him. At first he thought he was meant to take it in his, but then she opened her fist and he saw something in her palm. A small red-orange stone, like a shard of sunset.

“What is this?” he asked.

“The stone is called tsedukuu’,” she replied. “Ants bring them up from beneath the ground. They are thought to be lucky. This one is for your ear.”

“Oh,” he said. Now he saw the stone was set in a silver claw and had a small hook attached.

“I noticed you had some already,” she said, extending her lips to point.

He smiled and reached up to take out one of the four earrings in his right ear. He took the ring from her palm and put it in the now-empty piercing.

“Thank you,” he said. “It pleases me. But I have nothing for you.”

“Be a good husband,” she said. “Remember the things you said. It will be a fine present.”

“I won’t forget,” he said.

A breeze came across the desert. He closed his eyes to savor it.

“There are words, if you want to say them,” she said.

“Words?”

“Yes,” she replied. “I say neyeesheshuh. This means I’m asking you if you will accept my bride-gift.”

He smiled. It was all so quaint, but he was touched, and despite himself, flattered.

“Very well,” he said. “And I say the same thing?”

“Not exactly. You say hee’echuun.”

“That sounds like the way you said ‘hello.’”

“Same word,” she said. “It can also mean yes.”

“Hee’echuun,” he said, trying to get it right this time.

“That’s good!” she said. She beamed at him. “And now you say sheyeeneshuh.”

“Sheh-yaaaay-neh-shuh,” he managed, after several tries.

“Good enough!” she said. “This may work out, Chej. I am hopeful.”

DII JIN (THE PRESENT)

Eight days later, the conversation came back to haunt Chej like a hungry spirit when he was pulled from the purification rituals meant to prepare him for his wedding bed and rushed into the lesser council chamber, where he met with Zu the Bright, Master of the Bright Cloud Tower. Some people called him the Emperor’s Dog, although never to his face. Zu was an imposing man: tall, fat, old in appearance, his oiled grey-and-black hair pulled into one long braid. He wore a dark red robe over a gold-colored gown.

Zu informed him of the army now invading Zełtah. Chej thought he had misheard him at first. When he finally understood, he took a few moments before answering.

“But why?” he finally said. “I thought the marriage was to create an alliance between us and Zełtah. Why did the Emperor change his mind?”

“He did not,” Zu said. “The plan was always to invade once the marriage took place.”

“Why go through with the marriage, then?”

“There were a number of reasons. The barbarians usually live dispersed in their mountains, but they gathered at their fortress to wish their princess well. Dzhesq and Hsij infected them with various plagues. It was simpler with them all in one spot. They are a stubborn lot, and this will make them easier to conquer. Also, the princess will make an excellent hostage. It might make their eventual decision to surrender easier.”

Chej stared at Zu, horrified. “Why wasn’t I informed of this in advance?”

Zu wrinkled his brow in what appeared to be genuine puzzlement. Then he barked out a single unpleasant laugh.

“Why would you have been informed? It would only have given you a chance to botch the whole plan. As it is, they suspected nothing.” He shook his head. “There are those, Chej, that believe you are worthless in every way. But they overlook how amusing you can be at times. And I did find a use for you, didn’t I?”

Chej wanted to be indignant. Furious. Righteous. Instead, all he could think was that he should have known. He was a head taller than Zu, but at the moment he felt like an insect cowering before a giant.

“And what now?” he finally said. “Must I tell her?”

“Dzhesq has probably done that already. He seemed to relish being the bearer of the news.”

“Yes, he would, wouldn’t he?” Chej said.

“You can’t be disappointed,” Zu said. “After all, she’s hardly a beauty, is she? You needn’t get her with child. Xues is cousin to these people on his mother’s side. We can put him on the throne of Zełtah. And you can go back to doing… whatever it is you usually do.”

“I’m her husband.”

Zu rolled his eyes. “You are many things, Chej,” he said. “All meaningless. Let this be another of them. You will be happier.”

“As if you care about my happiness.”

“You are a child, Chej. You always will be. And now I have other things to attend to.”

Chej was well aware when he had been dismissed, but this time he felt he should say something. Do something.

But what? There was nothing to say or do that Zu wouldn’t consider a joke.

So he left, dragging his dignity behind him, reflecting that Zu was right: he didn’t have to face Yash now.

But then he thought of that night with Yash under the stars and reached to touch the earring she had given him.

She had come here in good faith, married him with the best of intentions for her people. If nothing else, he owed her a visit. It would probably not be pleasant. She would probably scream and cry and blame him for everything. But he could take that. He was used to that sort of thing.

CHAPTER FOUR

HSIJ THE YELLOW

CHEJ ARRIVED at the top of the Blue Needle Tower a little out of breath and still unsure what he was going to do or say when he saw Yash, puzzling at the scent of flowers permeating the upper stories. It was likely, he finally decided, that it was something Yash had brought with her, to remind her of her homeland.

When he reached the topmost rooms, he saw Yash immediately, standing at the window with her back to him. She no longer wore her wedding gown and had changed into a dark blue shift.

He was trying to think of how to announce his presence when she turned around and put her onyx gaze on him.

“Hee’echuun, shegan’,” she said.

That was her language. He remembered her lesson around the campfire, but he was notoriously bad at learning such things. He had been tutored in both the Moon Language and in Thengnawa. Both tutors had quit in frustration.

“I think that first means ‘hello’?” he said, after a few breaths. “Hechun?”

“Hee’echuun,” she corrected. “You make those sounds longer, see? Hechun sounds more like hechu, which means ‘egg.’ But that’s not bad. You have a good memory! Shegan means ‘husband.’ Or, rather, ‘my husband.’ Since a husband has to belong to someone.”

“True,” he said. He glanced around the room. There wasn’t much to see, but he found he was having a hard time looking her in the eyes.

“You’re uncomfortable,” she said. “Because your people have waged war on mine.”

“Ah—yes,” he replied. Zu said she knew. But the way she was acting—maybe she was still in shock. Maybe she didn’t really believe it yet. “I’m sorry,” he went on. “You seem to be—ah—taking it well.”

“I hoped it wouldn’t happen,” she said. “But I thought it might. How much do you know about it? The attack?”

“Not much,” he said. He knew he shouldn’t tell her anything, but she deserved to know. And he was her husband, after all, even if Zu and the rest thought of the whole thing as a farce. “They don’t tell me much. Only that they wanted your people to gather together so they could send plague demons while they were all in one place. Now they’ve sent an army. I don’t know how big. And they think you will make a good hostage.”

He stopped, feeling out of breath. Like he had just half-run half-fallen down a hill. Also, he was sure he had told her more than he meant to and far more than he was supposed to.

But what did it matter?

“It’s fine,” she said. “I’m not angry at you, you know.”

She seemed serious, but he didn’t know her all that well.

“Really?” he asked. “Because I’m pretty angry about it. I didn’t know this would happen. No one ever told me about this.” He paused. “I’ll understand if you don’t believe me.”

“I believe you,” she said.

He studied her for a moment, still trying to see if she was telling the truth or just attempting to make him feel better. She had no obligation to do either.

“I—” he began, not sure what he was going to say. But she held up her hand.

“Wait a moment, please,” she said. “I hear something.”

Chej didn’t hear anything, but an instant later he saw something. A large insect appeared on Yash’s shoulder. It had a long, slender jewel-green body with two pairs of translucent wings. A metal fly. They were common near the river and skimmed the canals, but seeing one up here in the fortress was a rare occurrence. He hadn’t seen it fly in.

“Where did that come from?” he asked.

“Hello, Deng’jah,” Yash said, glancing at the insect. “What kept you?”

“No time for long hellos,” the insect answered, in a voice that sounded almost like the strings of a wind-harp humming in a breeze, or like copper chimes or—something. Not human. “There are many guardians here. I was noticed.”

“Did that bug just talk?” Chej yelped.

“Go into the next room, shegan’,” Yash said. “Try to stay out of the way.”

Chej had a lot of questions about the talking insect. But the light coming through the window suddenly dimmed, and something in Yash’s voice made him think that he should just follow her advice and shut up.

As he crossed the threshold into the next room he turned and looked back, half hiding behind the doorway. Yash was where he had left her but had turned to face the window. She stood with her knees slightly bent, hands in front of her chest. Waiting. But for what?

Light was streaming through the window again, but once more a shadow fell across it, and this time he caught a glimpse of what was casting it: a gigantic bird, so close he could see the individual feathers and hear the whoosh of it passing. Chej relaxed a little.

“That’s Ruzuyer,” he told Yash. “He guards the fortress. He’s upset, but he’s too big to get in here.”

“That one isn’t, though,” Yash said, as a blue-grey cloud drifted in through the window. While Chej watched, the cloud swirled, tightening into a whirlwind and finally solidifying into a person.

“Hsij,” Chej said.

“Hello, Chej, you useless toad,” Hsij said.

Hsij the Yellow, Master of the Yellow Bone Tower was ancient, but he looked no older than a boy of sixteen or seventeen years. He kept his head shaved and oiled so that it gleamed in the evening light. He wore only a short red-and-black striped skirt held on by a black cord knotted in the front. More smoke blew in from behind him and formed four of his guards, all dressed in dull yellow armor of lacquered xewx chiton. All of them wielded fighting hatchets and small shields made of the same stuff as their armor.

“What is amiss here?” Hsij demanded, in his smooth, musical voice. His every word sounded almost like singing. “Ruzuyer is losing his mind. About something in here. What is it?”

“Hsij, I’ve no idea,” Chej said.

“I wasn’t asking you,” Hsij said. He took a step toward Yash. Chej noticed that the green bug was either gone or on her other shoulder, where he could not see it. She also looked more relaxed now—just standing there in a natural fashion.

Yash bowed her head in respect. “Master Hsij the Yellow, of the Yellow Bone Tower. It is an honor. But, you see, it is our wedding evening. We were hoping for privacy.”

“Ugh,” Hsij said, looking her up and down. “The very thought. I may vomit.” He walked around Yash, staring at her in an unseemly fashion, shaking his head. Then he stopped, his nostrils widening.

He nodded, turning his head and inhaling conspicuously. “That’s an interesting scent,” he said. “Something familiar about it. Something of yours, princess?”

She shook her head. “I noticed it on the way up,” she said. “When we passed Master Needle’s door.”

“I see,” Hsij said. “Perhaps I should pay Master Dzhesq a visit. Maybe he knows why Ruzuyer is so agitated. Princess, come along with me. Chej, you stay here.”

“I can come, too,” Chej said.

“No, you can’t,” Hsij replied. He nodded at one of his guards. “You stay here and keep Chej company. The rest of you, come with me. Princess, lead the way.”

“Of course,” she said. She waved at Chej. “I shall see you soon, Husband.”

He noticed this time she used the word in his language, hesrem, for husband.

He watched them go. The remaining guard placed himself in the doorway to the room Chej had gone into.

“Move back,” he directed.

Chej did as he was told. The room was rather small, containing little more than a washbasin, a jug of water to fill it, three stools, and a small table where some clothes were stacked. He took a seat on one of the stools, his legs still tired from traversing the seemingly endless flights of stairs in the Blue Needle Tower.

What could be happening? Had the metal fly really spoken? Or was he losing his mind? Maybe Yash had done something artful with her voice, like the entertainers who made puppets seem to speak? Had she been trying to amuse him?

But now he was remembering the stories about the Lords of Decay, and how they used metal flies as walking sticks. Could the insect be an evil spirit? Did that mean Yash was a sorcerer?

And what did Hsij the Yellow intend with his bride? Hsij was the most volatile of the masters. You could never tell what he was going to do. Had Hsij taken a notion to murder Yash?

If so, Chej should do something about it. Or at least try. He was, after all, a hje as well as her husband. He should have some say in the matter. Yash had done nothing to deserve how she was being treated. Nothing but being born a barbarian. And maybe he would have thought of her that way a year before. But since visiting Zełtah, he had formed a somewhat favorable impression of her people. The disdain his family showed them—and her—was unearned. And the way people kept calling Yash ugly was starting to irritate him. Her looks suited her. In fact, he had never seen anyone who looked so much like who she really was. He should tell her that. If he saw her again.

What if Hsij really did mean Yash harm? What could he do, with the guard standing there? Maybe he could talk to the man. Convince him to let him go. But he couldn’t start with that, could he?

“Is it strange, traveling as smoke like that?” Chej asked the man.

“A little,” the man said. “But I’ve served Master Yellow for ten years, so I’m used to it.”

“What does it feel like?”

The guard started to answer, but then he looked away as if something else was demanding his attention.

“What’s wrong?” Chej asked.

“I heard something.”

“Perhaps Hsij is calling you?”

“No, not like that,” the guard said. “Stay here.” He walked away then came back and shrugged.

“I guess my ears are fooling me,” he said.

Chej heard a weird, meaty thump. The guard took a step toward him and then crumpled. To his horror, Chej saw the man had a war hatchet buried in the back of his skull.

“Shit!” he swore, jumping up from his stool.

Then Yash walked into view. Her face and dress were spattered in red and she had a knife in one hand.

“I hope you weren’t bored,” she said. “I hurried back as soon as I could.”

“What—what is happening? What did you do?”

“There were four of them,” she said, brightly. “Hsij was the hardest. Did you know his skin was enchanted against weapons? Not his eyes, though.”

“What?” Chej said. “Is there something down there? Did one of Dzhesq’s monsters escape?”

“No,” Yash said. “At least, I don’t think so. Everything down there is dead. But I need your help.”

He looked at the dead guard. Yash had killed him, hadn’t she? With an axe.

“H—help you?”

“Yes! Let’s drag this guard down to where the rest of them are. And we should try not to get too much blood on the floor. Though at this point, we may be beyond that.”

Numbly, Chej stood, realizing he was going to do as she asked. It seemed like the easiest thing to do.