Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

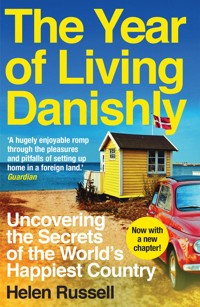

* NOW WITH A NEW CHAPTER * 'A hugely enjoyable romp through the pleasures and pitfalls of setting up home in a foreign land.'- Guardian Given the opportunity of a new life in rural Jutland, Helen Russell discovered a startling statistic: Denmark, land of long dark winters, cured herring, Lego and pastries, was the happiest place on earth. Keen to know their secrets, Helen gave herself a year to uncover the formula for Danish happiness. From childcare, education, food and interior design to SAD and taxes, The Year of Living Danishly records a funny, poignant journey, showing us what the Danes get right, what they get wrong, and how we might all live a little more Danishly ourselves. In this new edition, six years on Helen reveals how her life and family have changed, and explores how Denmark, too – or her understanding of it – has shifted. It's a messy and flawed place, she concludes – but can still be a model for a better way of living.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 532

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

Praise for The Year of Living Danishly

‘A lovely mix of English sensibility and Danish pragmatism. Helen seems to have understood more about the Danish character than I have! My only worry is that it will make everyone want to have a go and my holiday home area will get overcrowded.’

Sandi Toksvig

‘Russell is possessed of a razor-sharp wit and a winning self-deprecation – two of the things that make this book such a delight.’

The Independent

‘A hugely enjoyable romp through the pleasures and pitfalls of setting up home in a foreign land.’

P.D. Smith, Guardian

‘A wryly amusing account of a new life in a strange land.’

Choice Magazine

‘A hugely enjoyable autobiographical account of upping sticks … to the sticks.’

National Geographic Traveller

iii

v

For Little Red, Lego Man and the woman in the salopettes-’n’-beret combo.

vi

Contents

Prologue

Making Changes – The Happiness Project

It all started simply enough. After a few days off work my husband and I were suffering from post-holiday blues and struggling to get back into the swing of things. A grey drizzle had descended on London and the city looked grubby and felt somehow worn out – as did I. ‘There has to be more to life than this…’ was the taunt that ran through my head as I took the tube to the office every day, then navigated my way home through chicken bone-strewn streets twelve hours later, before putting in a couple of hours of extra work or going to events for my job. As a journalist on a glossy magazine, I felt like a fraud. I spent my days writing about how readers could ‘have it all’: a healthy work-life balance, success, sanity, sobriety – all while sporting the latest styles and a radiant glow. In reality, I was still paying off student loans, relying on industrial quantities of caffeine to get through the day and self-medicating with Sauvignon Blanc to get myself to sleep.

Sunday evenings had become characterised by a familiar tightening in my chest at the prospect of the week ahead, xand it was getting harder and harder to keep from hitting the snooze button several times each morning. I had a job I’d worked hard for in an industry I’d been toiling in for more than a decade. But once I got the role I’d been striving towards, I realised I wasn’t actually any happier – just busier. What I aspired to had become a moving target. Even when I reached it, there’d be something else I thought was ‘missing’. The list of things I thought I wanted, or needed, or should be doing, was inexhaustible. I, on the other hand, was permanently exhausted. Life felt scattered and fragmented. I was always trying to do too many things at once and always felt as though I was falling behind.

I was 33 – the same age Jesus got to, only by this point he’d supposedly walked on water, cured lepers and resurrected the dead. At the very least he’d inspired a few followers, cursed a fig tree, and done something pretty whizzy with wine at a wedding. But me? I had a job. And a flat. And a husband and nice friends. And a new dog – a mutt of indeterminate breeding that we’d hoped might bring a bucolic balance to our hectic urban lives. So life was OK. Well, apart from the headaches, the intermittent insomnia, the on/off tonsillitis that hadn’t shifted despite months of antibiotics and the colds I seemed to come down with every other week. But that was normal, right?

I’d thrived on the adrenaline of city life in the past, and the bright, buzzy team I worked with meant that there was never a dull moment. I had a full social calendar and a support network of friends I loved dearly, and I lived in one of the most exciting places in the world. But after twelve years at full pelt in the country’s capital and the second stabbing xiin my North London neighbourhood in as many months, I suddenly felt broken.

There was something else, too. For two years, I had been poked, prodded and injected with hormones daily only to have my heart broken each month. We’d been trying for a baby, but it just wasn’t working. Now, my stomach churned every time a card and a collection went round the office for some colleague or other off on maternity leave. There are only so many Baby Gap romper suits you can coo over when it’s all you’ve wanted for years – all your thrice-weekly hospital appointments have been aiming for. People had started to joke that I should ‘hurry up’, that I wasn’t ‘that young any more’ and didn’t want to ‘miss the boat’. I would smile so hard that my jaw would ache, while trying to resist the urge to punch them in the face and shout: ‘Bugger off!’ I’d resigned myself to a future of IVF appointments fitted in around work, then working even more in what spare time I had to keep up. I had to keep going, to stop myself from thinking too much and to maintain the lifestyle I thought I wanted. That I thought we needed. My other half was also feeling the strain and would come home furious with the world most nights. He’d rant about bad drivers or the rush-hour traffic he’d endured on his 90-minute commute to and from work, before collapsing on the sofa and falling into a Top Gear/trash TV coma until bed.

My husband is a serious-looking blond chap with a hint of the physics teacher about him who once auditioned to be the Milky Bar kid. He didn’t have a TV growing up so wasn’t entirely sure what a Milky Bar was, but his parents had seen an ad in the Guardian and thought it sounded wholesome. xiiAnother albino-esque child got the part in the end, but he remembers the day fondly as the first time he got to play with a handheld Nintendo that another hopeful had brought along. He also got to eat as much chocolate as he liked – something else not normally allowed. His parents eschewed many such new-fangled gadgets and foodstuffs, bestowing on him instead a childhood of classical music, museum visits and long, bracing walks. I can only begin to imagine their disappointment when, aged eight, he announced that his favourite book was the Argos catalogue; a weighty tome that he would sit with happily for hours on end, circling various consumer electronics and Lego sets he wanted. This should have been an early indicator of what was in store.

He came along at a time in my life when I had just about given up hope. 2008, to be exact. My previous boyfriend had dumped me at a wedding (really), and the last date I’d been on was with a man who’d invited me round for dinner before getting caught up watching football on TV and so forgetting to buy any food. He said he’d order me a Dominos pizza instead. I told him not to bother. So when I met my husband-to-be and he offered to cook, I wasn’t expecting much. But supper went surprisingly well. He was clever and funny and kind and there were ramekins involved. My mother, when I informed her of this last fact, was very impressed. ‘That’s the sign of a very well brought up young man,’ she told me, ‘to own a set of ramekins. Let alone to know what to do with them!’

I married him three years later. Mostly because he made me laugh, ate my experimental cooking and didn’t complain when I mineswept the house for sweets. He could also be xiiiincredibly irritating – losing keys, wallet, phone or all of the above on a daily basis, and having an apparent inability to arrive anywhere on time and an infuriating habit of spending half an hour in the loo (‘are you redecorating in there?’). But we were all right. We had a life together. And despite the hospital visits and low-level despair/exhaustion/viruses/financial worries at the end of each month (due to having spent too much at the start of each month), we loved each other.

I’d imagined a life for us where we’d probably move out of London in a few years’ time, work, see friends, go on holidays, then retire. I envisaged seeing out my days as the British version of Jessica Fletcher from Murder She Wrote: writing and solving sanitised crime, followed by a nice cup of tea and a laugh-to-credits ending. My fantasy retirement was going to rock. But when I shared this vision with my husband, he didn’t seem too keen. ‘That’s it?’ was his response. ‘Everyone does that!’

‘Were you not listening,’ I tried again, ‘to the part about Jessica Fletcher?’

He began to imply that Murder She Wrote was a work of fiction, to which I scoffed and said that next he’d be telling me that unicorns weren’t real. Then he stopped me in my tracks by announcing that he really wanted to live overseas someday.

‘“Overseas”?’ I checked I’d got this bit right: ‘As in, “not in this country”? Not near our seas?’

‘Yes.’

‘Oh.’

I’m not someone who relishes adventure, having had xivmore than my fair share of it growing up and in my twenties. Nowadays, I crave stability. When the prospect of doing anything daring is dangled in front of me, I have a tendency to weld myself to my comfort zone. I’m even scared of going off piste on a menu. But my husband, it seemed, wanted more. This frightened me, making me worry that I wasn’t ‘enough’ for him, and the seed of doubt was planted. Then one wet Wednesday evening, he told me he’d been approached about a new job. In a whole other country.

‘What? When did this happen?’ I demanded, suspicious that he’d been applying for things on the sly.

‘Just this morning,’ he said, showing me an email that had indeed come out of the blue earlier that day, getting in touch and asking whether he’d be interested in relocating … to Denmark. The country of pastries, bacon, strong fictional females and my husband’s favourite childhood toy. And it was the makers of the small plastic bricks who were in search of my husband’s services.

‘Lego?’ I asked, incredulous as I read the correspondence. ‘You want us to move to Denmark so you can work for Lego?’ Was he kidding me? Were we in some screwed-up sequel to that Tom Hanks film where grown-ups get their childhood wishes granted? What next? Would Sylvanian Families appoint me their woodland queen? Were My Little Pony about to DM me inviting me to become their equine overlord? ‘How on earth has this happened? And was there a genie or a malfunctioning fairground machine involved?’

My husband shook his head and told me that he didn’t know anything about it until today – that a recruitment agent he’d been in touch with ages ago must have put him forward. xvThat it wasn’t something he actively went looking for but now it was here, well, he hoped we could at least consider it.

‘Please?’ he begged. ‘For me? I’d do it for you. And we could move for your job next time,’ he promised.

I didn’t think that this was an entirely fair exchange: he knew full well that I’d happily stay put forever in a nice little town just outside the M25 to execute Project Jessica Fletcher. Denmark had never been a part of my plan. But this was something that he really wanted. It became our sole topic of conversation outside work over the next week and the more we talked about it, the more I understood what this meant to him and how much it mattered. If I denied him this now, a year into our marriage, how would that play out in future? Did I really want it to be one of the things we regretted? Or worse, that he resented me for? I loved him. So I agreed to think about it.

We went to Denmark on a recce one weekend and visited Legoland. We laughed at how slowly everyone drove and spluttered at how much a simple sandwich cost. There were some clear attractions: the place was clean, the Danish pastries surpassed expectations, and the scenery, though not on the scale of the more dramatic Norwegian fjords, was soul-lifting.

While we were there, a sense of new possibilities started to unfurl. We caught a glimpse of a different way of life and noticed that the people we met out there weren’t like folks back home. Aside from the fact that they were all strapping Vikings, towering over my 5′3″ frame and my husband’s 5′11″-on-a-good-day stature, the Danes we met didn’t look like us. They looked relaxed. They walked more slowly. They xvitook their time, stopping to take in their surroundings. Or just to breathe.

Then we came home, back to the daily grind. And despite my best efforts, I couldn’t get the idea out of my head, like a good crime plot unravelling clue by clue. The notion that we could make a change in the way we lived sparked unrest, where previously there’d been a stoic acceptance. Project Jessica Fletcher suddenly seemed a long way off, and I wasn’t sure I could keep going at the same pace for another 30 years. It also occurred to me that wishing away half your life in anticipation of retirement (albeit an awesome one) was verging on the medieval. I wasn’t a serf, tilling the land until I dropped from exhaustion. I was working in 21st century London. Life should have been good. Enjoyable. Easy, even. So the fact that I was dreaming of retirement at the age of 33 was probably an indicator that something had to change.

I couldn’t remember the last time I’d been relaxed. Properly relaxed, without the aid of over-the-counter sleeping tablets or alcohol. If we moved to Denmark, I daydreamed, we might be able to get better at this ‘not being so stressed all the time’ thing … We could live by the sea. We could walk our dog on the beach every day. We wouldn’t have to take the tube anymore. There wouldn’t even be a tube where we’d be moving to.

After our weekend of ‘other life’ possibilities, we were faced with a choice. We could stick with what we knew, or we could take action, before life became etched on our foreheads. If we were ever going to try to lead a more fulfilling existence, we had to start doing things differently. Now.

My husband, a huge Scandophile, was already sold on xviiDenmark. But being more cautious by nature, I still needed time to think. As journalist, I needed to do my research.

Other than Sarah Lund’s Faroe Isle jumpers, Birgitte Nyborg’s bun and Borgen creator Adam Price’s knack of making coalition politics palatable for prime time TV, I knew very little about Denmark. The Nordic noir I’d watched had taught me two things: that the country was doused in perpetual rain and people got killed a lot. But apparently it was also a popular tourist destination, with official figures from Visit Denmark showing that numbers were up 26 per cent. I learned too that the tiny Scandi-land punched above its weight commercially, with exports including Carlsberg (probably the best lager in the world), Arla (the world’s seventh biggest dairy company and the makers of Lurpak), Danish Crown (where most of the UK’s bacon comes from) and of course Lego – the world’s largest toymaker. Not bad for a country with a population of 5.5 million (about the size of South London).

‘Five and a half million!’ I guffawed when I read this part. I was alone in the flat with just the dog for company, but he was doing his best to join in the conversation by snorting with incredulity. Or it might have been a sneeze. ‘Does five and a half million even qualify as a country?’ I asked the dog. ‘Isn’t that just a big town? Do they really even need their own language?’ The dog slunk off as though this question was beneath him, but I carried on unperturbed.

I discovered that Denmark had been ranked as the EU’s most expensive country to live in by Ireland’s Central Statistics Office, and that its inhabitants paid cripplingly high taxes. Which meant that we would, too. Oh brilliant! xviiiWe’ll be even more skint by the end of the month than we are already… But for your Danish krone, I learned, you got a comprehensive welfare system, free healthcare, free education (including university tuition), subsidised childcare and unemployment insurance guaranteeing 80 per cent of your wages for two years. Denmark, I was informed, also had one of the smallest gaps between the very poor and the very rich. And although no country in the world had yet achieved true gender equality, Denmark seemed to be coming close, thanks to a female PM (at the time of writing) and a slew of strong women in leadership positions. Unlike in the US and the UK, where already stressed out and underpaid women were being told to ‘lean in’ and do more, it looked like you could pretty much lean any way you fancied in Denmark and still do OK. Oh, and women weren’t handed sticks to beat themselves with if they weren’t ‘having it all’. This, I decided, was refreshing.

Whereas in the US and the UK we’d fought for more money at work, Scandinavians had fought for more time – for family leave, leisure and a decent work-life balance. Denmark was regularly cited as the country with the shortest working week for employees, and the latest figures showed that Danes only worked an average of 34 hours a week (according to Statistic Denmark). By comparison, the Office of National Statistics found that Brits put in an average of 42.7 hours a week. Instead of labouring around the clock and using the extra earnings to outsource other areas of life – from cooking to cleaning, gardening, even waxing – Danes seemed to adopt a DIY approach.

Denmark was also the holder of a number of world xixrecords – from having the world’s best restaurant, in Copenhagen’s Noma, to being the most trusting nation and having the lowest tolerance for hierarchy. But it was the biggie that fascinated me: our potential new home was officially the happiest country on earth. The UN World Happiness Report put this down to a large gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, high life expectancy, a lack of corruption, a heightened sense of social support, freedom to make life choices and a culture of generosity. Scandinavian neighbours Norway and Sweden nuzzled alongside at the top of the happy-nation list, but it was Denmark that stood out. The country also topped the UK Office of National Statistics’ list of the world’s happiest nations and the European Commission’s well-being and happiness index – a position it had held onto for 40 years in a row. Suddenly, things had taken a turn for the interesting.

‘Happy’ is the holy grail of the lifestyle journalist. Every feature I’d ever written was, in some way, connected to the pursuit of this elusive goal. And ever since defacing my army surplus bag with the lyrics to the REM song in the early 1990s, I’d longed to be one of those shiny, happy people (OK, so I missed the ironic comment on communist propaganda, but I was only twelve at the time).

Happy folk, I knew, were proven to earn more, be healthier, hang on to relationships for longer and even smell better. Everyone wanted to be happier, didn’t they? We certainly spent enough time and money trying to be. At the time of researching, the self-help industry was worth $11 billion in the US and had earned UK publishers £60 million over the xxlast five years. Rates of antidepressant use had increased by 400 per cent in the last fifteen years and were now the third most-prescribed type of medication worldwide (after cholesterol pills and painkillers). Even those lucky few who’d never so much as sniffed an SSRI or picked up a book promising to boost their mood had probably used food, booze, caffeine or a credit card to bring on a buzz.

But what if happiness isn’t something you can shop for? I could almost feel the gods of lifestyle magazines preparing to strike me down as I contemplated this shocking thought. What if happiness is something more like a process, to be worked on? Something you train the mind and body into? Something Danes just have licked?

One of the benefits of being a journalist is that I get to be nosy for a living. I can call up all manner of interesting people under the pretext of ‘research’, with the perfect excuse to ask probing questions. So when I came across Denmark’s ‘happiness economist’ Christian Bjørnskov, I got in touch.

He confirmed my suspicions that our Nordic neighbours don’t go in for solace via spending (thus ruling out 90 per cent of my usual coping strategies).

‘Danes don’t believe that buying more stuff brings you happiness,’ Christian told me. ‘A bigger car just brings you a bigger tax bill in Denmark. And a bigger house just takes longer to clean.’ In an approximation of the late, great Notorious B.I.G.’s profound precept, greater wealth means additional anxieties, or in Danish, according to my new favourite app, Google Translate, the somewhat less catchy ‘mere penge, mere problemer’.xxi

So what did float the Danes’ boats? And why were they all so happy? I asked Christian, sceptically, whether perhaps Danes ranked so highly on the contented scale because they just expected less from life.

‘Categorically not,’ was his instant reply. ‘There’s a widely held belief that Danes are happy because they have low expectations, but when Danes were asked about their expectations in the last European study, it was revealed that they were very high and they were realistic.’ So Danes weren’t happy because their realistic expectations were being met; they were happy because their high expectations were also realistic? ‘Exactly.’

‘There’s also a great sense of personal freedom in Denmark,’ said Christian. The country is known for being progressive, being the first to legalise gay marriage and the first European country to allow legal changes of gender without sterilisation.

‘This isn’t just a Scandinavian thing,’ Christian continued. ‘In Sweden, for instance, many life choices are still considered taboo, like being gay or deciding not to have children if you’re a woman. But deciding you don’t want kids when you’re in your thirties in Denmark is fine. No one’s going to look at you strangely. There’s not the level of social conformity that you find elsewhere.’

That’s not to say that your average Dane wasn’t conforming in other ways, Christian warned me. ‘We all tend to look very much alike,’ he told me. ‘There’s a uniform, depending on your age and sex.’ Females under 40 apparently wore skinny jeans, loose-fitting T-shirts, leather jackets, an artfully wound scarf and a topknot or poker-straight blonde xxiihair. Men under 30 sported skinny jeans, high tops, slogan or band T-shirts and 90s bomber jackets with some sort of flat-top haircut. Older men and women preferred polo shirts, sensible shoes, slacks and jackets. And everyone wore square Scandi-issue black-rimmed glasses. ‘But ask a Dane how they’re feeling and what they consider acceptable and you’ll get more varied answers,’ said Christian. ‘People don’t think much is odd in Denmark.’

He explained how social difference wasn’t taken too seriously and used the example of the tennis club to which he belonged. This immediately conjured up images of WASP-ish, Hampton’s-style whites, Long Island iced tea, and bad Woody Allen films but Christian soon set me straight. ‘In Denmark, there’s no social one-upmanship involved in joining a sports club – you just want to play sports. Lots of people join clubs here, and I play tennis regularly with a teacher, a supermarket worker, a carpenter and an accountant. We are all equal. Hierarchies aren’t really important.’

What Danes really cared about, Christian told me, was trust: ‘In Denmark, we trust not only family and friends, but also the man or woman on the street – and this makes a big difference to our lives and happiness levels. High levels of trust in Denmark have been shown time and time again in surveys when people are asked, “Do you think most people can be trusted?” More than 70 per cent of Danes say: “Yes, most people can be trusted.” The average for the rest of Europe is just over a third.’

This seemed extraordinary to me – I didn’t trust 70 per cent of my extended family. I was further gobsmacked when Christian told me that Danish parents felt their children xxiiiwere so safe that they left babies’ prams unattended outside homes, cafés and restaurants. Bikes were apparently left unlocked and windows were left open, all because trust in other people, the government and the system was so high.

Denmark has a miniscule defence budget and, despite compulsory national service, the country would find it almost impossible to defend itself if under attack. But because Denmark has such good relations with its neighbours, there is no reason to fear them. As Christian put it: ‘Life’s so much easier when you can trust people.’

‘And does Denmark’s social welfare system help with this?’ I asked.

‘Yes, to an extent. There’s less cause for mistrust when everyone’s equal and being looked after by the state.’

So what would happen if a more right-wing party came to power or the government ran out of money? What would become of the fabled Danish happiness if the state stopped looking after everyone?

‘Happiness in Denmark isn’t just dependent on the welfare state, having Social Democrats in power or how we’re doing in the world,’ Christian explained. ‘Danes want Denmark to be known as a tolerant, equal, happy society. Denmark was the first European country to abolish slavery and has history as a progressive nation for gender equality, first welcoming women to parliament in 1918. We’ve always been proud of our reputation and we work hard to keep it that way. Happiness is a subconscious process in Denmark, ingrained in every area of our culture.’

By the end of our call, the idea of a year in Denmark had started to sound (almost) appealing. It might be good to be xxivable to hear myself think. To hear myself living. Just for a while. When my husband got home, I found myself saying in a very small voice, that didn’t seem to be coming out of my mouth, something along the lines of: ‘Um, OK, yes … I think … let’s move.’

Lego Man, as he shall henceforth be known, did a rather fetching robotics-style dance around the kitchen at this news. Then he got on the phone to his recruitment consultant and I heard whooping. The next day, he came home with a bottle of champagne and a gold Lego mini-figure keyring that he presented to me ceremoniously. I thanked him with as much enthusiasm as I could muster and we drank champagne and toasted our future.

‘To Denmark!’

From a vague idea that seemed unreal, or at least a long way off, plans started to be made. We filled in forms here, chatted to relocation agents there and started to tell people about our intention to up sticks. Their reactions were surprising. Some were supportive. A lot of people told me I was ‘very brave’ (I’m really not). A couple said that they wished they could do the same. Many looked baffled. One friend quoted Samuel Johnson at me, saying that if I was tired of London I must be tired of life. Another counselled us, in all seriousness, to ‘tell people you’re only going for nine months. If you say you’re away for a year, no one will keep in touch – they’ll think you’re gone for good.’ Great. Thanks.

When I resigned from my good, occasionally glamorous job, I faced a similarly mixed response. ‘Are you mad?’, ‘Have you been fired?’ and ‘Are you going to be a lady of leisure?’ were the three most common questions. ‘Possibly’, xxv‘No’ and ‘Certainly not’, were my replies. I explained to colleagues that I planned to work as a freelancer, writing about health, lifestyle and happiness as well as reporting on Scandinavia for UK newspapers. A few whispered that they’d been thinking of taking the freelance plunge themselves. Others couldn’t get their heads around the idea. One actually used the term, ‘career suicide’. If I hadn’t been terrified before, I was now.

‘What have I done?’ I wailed, several times a day. ‘What if it doesn’t work out?’

‘If it doesn’t work out, it doesn’t work out,’ was Lego Man’s pragmatic response. ‘We give it a year and if we don’t like it, we come home.’

He made it all sound simple. As though we’d be fools not to give it a go.

So, after welling up on my last day at work, I came home and carefully wrapped up the dresses, blazers and four-inch heels that had been my daily uniform for more than a decade and packed them away. I wouldn’t need these where we were headed.

One Saturday, six removal men arrived at our tiny basement flat demanding coffee and chocolate digestives. Between us, we packed all our worldly possessions into 132 boxes before loading them into a shipping container to be transported to the remote Danish countryside. This was happening. We were moving. And not to some cosy expat enclave of Copenhagen. Just as London is not really England, Copenhagen is not, I am reliably informed, ‘the real Denmark’. Where we were going, we wouldn’t need an A–Z, a tube pass or my Kurt Geiger discount card. Where xxviwe were going, all I’d need were wellies and a weatherproof mac. We were heading to the Wild West of Scandinavia: rural Jutland.

The tiny town of Billund to the south of the peninsular had a population of just 6,100. I knew people with more Facebook friends than this. The town was home to Lego HQ, Legoland and … well, that was about it, as far as I could make out.

‘You’re going somewhere called “Bell End”?’ was a question I got from family and friends more times than I care to remember. ‘Billund,’ I’d correct them. ‘Three hours from Copenhagen.’

If they sounded vaguely interested, I’d elaborate and tell them about how a carpenter called Ole Kirk Christiansen started out in the town in the 1930s. How, in true Hans Christian Andersen style, he was a widower with four children to feed who started whittling wooden toys to make ends meet. How he went on to produce plastic building blocks under the name ‘Lego’, from the Danish phrase ‘leg godt’, meaning ‘play well’. And how my husband was going to work for the toymaker. Those curious to know more usually had a Lego fan in their household. Those without children tended to ask about opportunities for winter sports.

‘So, Denmark, it’s cold there, right?’

‘Yes. It’s Baltic. Literally.’

‘So, er, can you ski or snowboard?’

‘I can, yes. But not in Denmark.’

Then I’d have to break it to them that the highest point in the whole country was only 171 m above sea level and that you’d have to travel to Sweden for skiing. xxvii

‘Oh well, it’s all Scandinavia, isn’t it?’ was the typical response from those angling for a free chalet, to which I’d have to explain that, sadly, the closest resort was 250km away.

Many struggled to get their heads around precisely which of the Nordic countries we were moving to, with various leaving cards wishing us the ‘Best of luck in Finland!’ and my mother telling everyone we were off to Norway. In many respects, it may as well have been. The downshift from London life to rural Scandinavia was always going to be a shock to the system.

Once the removal men had gone, all we had left was a suitcase of clothes and the entire contents of our drinks cabinet, which apparently we weren’t allowed to export due to customs laws. We convened an ad hoc ‘drink the flat dry’ party in response to this, but it turns out that drinking three-year-old limoncello from a plastic cup in a cold, empty room on a school night isn’t quite as jolly as it might sound. Everyone had to stand or sit on the floor and voices echoed around the furniture-less space. There was no sense of occasion and it wasn’t anything like the epic, cinematic send-offs that you see in films. For most people, life was carrying on as normal. Us leaving the country wasn’t much of a big deal to anyone other than a few close friends and family. Some made an effort. One friend brought over mini Battenbergs and a thermos of tea (we had no kettle, let alone tea bags by this point). I was so ridiculously grateful, I could have wept. Thinking back, I may have done. Another made a photo montage of our time together in the capital. A third lent us a lilo to sleep on for our final night. xxviii

A damp, Edwardian terraced flat with no furniture, in winter, in the dead of night, is a very sad place indeed. We lay uncomfortably on the not-quite-double lilo and tried to stay still lest we bounce the other person off onto the hard wooden floor. Eventually, Lego Man started to breathe more deeply so that I knew he was asleep. Unable to join him, I stared at the crack in the ceiling in the shape of a question mark that we’d planned to fill in ages ago. It felt as though we’d lost everything, or we were squatters, or had just gone through a divorce, despite the fact that we were lying next to each other. Just for that night, we had nothing. I stared at the plaster question mark for what felt like hours until the street lamp outside the window went off and we were finally plunged into total darkness.

The next day we had lunch with family and a couple of close friends in a café near our flat. There were chairs! And plates! It was heaven. There were also tears (mine, my mother’s, and those of a school friend whose alcohol tolerance had been severely diminished by the recent arrival of twins), as well as beer, gin and gifts of several more Scandi box sets to get us in the mood. And then, a few hours later, the taxi arrived to take us to the airport. I suddenly wanted to linger longer in London, to take in every detail of the city as we drove through it by dusk, to memorise every twinkling light along the river so that I could keep hold of it until I next came back for a visit. I wanted to Have A Moment. But the driver wasn’t the sentimental type. Instead he turned on some hard-core US rap and unwrapped a Magic Tree air freshener.

We sat in silence after this. I kept my mind occupied by xxixgoing over and over my plan of action, ‘keep busy, then you can’t be sad!’ being the mildly manic philosophy I’d adhered to for the past 33 years. My loosely thought-out plan was this: to integrate as far as possible in an attempt to understand Denmark and what made its inhabitants so happy. Up to this point, my typical New Year’s Resolutions consisted of ‘do more yoga’, ‘read Stephen Hawking’ and ‘lose half a stone’. But this year, there was to be just one: ‘live Danishly’. Yes, I even invented a new Nordic adverb for the project. Over the next twelve months, I would investigate all aspects of living Danishly. I would consult experts in their fields and beg, bully or bribe them to share their secrets of the famed Danish contentment, and demonstrate how Danes do things differently.

I had been checking the weather in Denmark on an hourly basis during our last few days in London, prompting my first question – how do Danes stay upbeat when it’s minus ten every day? Revelations about how much we’d both take home after taxes were also eye-opening. Doesn’t a 50 per cent tax rate really stick in everyone’s craw? Lego Man remained stoic in the face of possible penury and focussed instead on all the great examples of Scandinavian design that kept being featured in weekend living supplements. Could the much-celebrated Danish aesthetic influence the nation’s mood? I wondered. Or are they just high on dopamine from all those pastries?

From education to the environment, genetics to gynaecological chairs (really), and family to food (seriously, have you tried a freshly baked pastry from Denmark? They’re delicious. Why wouldn’t Danes be delighted with life?), I xxxdecided I would set out to discover the key to getting happy in every area of modern life. I would learn something new each month and make changes to my own life accordingly. I was embarking on a personal and professional quest to discover what made Danes feel so great. The result would, I hoped, be a blueprint for a lifetime of contentment. The happiness project had begun.

To ensure that each of my teachers walked the talk, I would ask every expert to rank themselves on a happiness scale between one and ten, with ten being delirious, zero being miserable, and the middling numbers being a bit ‘meh’. As someone who’d typically have placed herself at a perfectly respectable six before my year of living Danishly, this proved an interesting exercise. Despite having been commended for Julie Andrews-style upbeat cheerfulness in every work-leaving card I’d ever had, I soon learned that there’s a difference between eager-to-please nice-girl syndrome and feeling genuinely good about yourself. I’d asked Christian for his score during our preliminary phone call, and he admitted that ‘Even being Danish can’t make everything absolutely perfect,’ but then followed up with, ‘I’d give myself an eight’. Not bad. So what would have made the professor of happiness even happier? ‘Getting a girlfriend,’ he told me, without hesitation. Anyone interested in a date with Denmark’s most eligible professor can contact the publisher for more details. For everyone else, here’s how to get happy, Danish-style.

1. January

Hygge & Home

Something cold and soft is falling on us as we stand in darkness on a silent runway, wondering what happens next. Before we’d boarded the flight it had been muggy, bright and noisy. We’d been pushed and barged by other passengers, ushered onto buses and shuffled around by ground staff. Mid-air, we’d been looked after by stewards in smart navy uniforms, plying us with miniatures and tiny cans of Schweppes. But here we are on our own, left standing on the frosty tarmac in the middle of nowhere. There are a few people around, of course, but we don’t know any of them and they’re all speaking a language we don’t understand. The whole place glistens like it’s made from soda crystals, and the air is so cold and thin that it catches in the back of my throat when I attempt to fill my lungs.

‘What now?’ I start, but the sound is muffled by snow. My ears already hurt from the chill so I cover them with my hair in lieu of a hat. This is surprisingly effective, though now I can hear even less. Lego Man’s lips are moving but I can’t quite make out what he’s saying, so we resort to hand signals.

‘This way?’ he mouths, pointing to the white building up 2ahead. I give him an 80s high school movie-style thumbs up: ‘OK.’

A woman with a wheelie bag appears from behind us and moves decisively towards a small rectangle of light up ahead, so we follow, crunching compacted snow as we go. There’s no shuttle bus or covered walkway here – Vikings, it seems, make their own way.

My husband squeezes my near-frozen hand and I try to smile, but because my teeth are chattering so much now, it comes out as more of a grimace. I knew it would be cold here, but this is something else. We’ve been exposed to the Baltic air for all of 90 seconds and the chill is gnawing at my very bones. My nose threatens to drip but then the tickling sensation stops and I lose all feeling in the tip. Oh God, does even snot freeze in Denmark? I wonder. I’m relieved to get inside to passport control and my toes and fingers burn with relief at the relative warmth.

We pass a giant sign advertising the country’s most famous beer that reads: ‘Welcome to the world’s happiest nation!’

Huh, I think, we’ll see.

We know no one, we don’t speak Danish, and we have nowhere to live. The whole take-a-punt, ‘new year, new you’ euphoria has now been replaced by a sense of: ‘Oh shit, this is real’. The two-day hangover from extended farewell celebrations and our boozy leaving lunch probably isn’t helping either.

We emerge from arrivals into a frozen, pitch-black nothingness and go in search of our hire car. This isn’t as easy as it 3might be since all the number plates have been fuzzed-out by frost, like in a police reconstruction. Once the correct combination of letters and numbers has been located, we drive, on the wrong side of the road, to Legoland. After several wrong turns due to unfamiliar road signs, partially whited-out by snow, we reach the place we’re to call home for the next few nights.

‘Welcome to the Legoland Hotel!’ the tall, broad, blond-haired receptionist beams as we check in. His English is perfect and I’m relieved. Christian had assured me that most Danes were proficient linguists, but I’d been warned not to expect too much in rural areas, i.e. where we are. But so far, so good.

‘We’ve put you in The Princess Suite,’ the receptionist goes on.

‘“The Princess Suite”?’ Lego Man echoes.

‘Is that at all like the presidential suite?’ I ask, hopefully.

‘No, it’s themed.’ The receptionist swivels around his monitor to show us a pastel-coloured room complete with a pink bed and a headboard made from plastic moulded castle turrets. ‘See?’

‘Wow. Yes, I see…’

The receptionist goes on: ‘The suite is built with 11,960 Lego bricks—’

‘—Right, yes. The thing is—’

‘—and it’s got bunk beds,’ he adds, proudly.

‘That’s great. It’s just, the thing is, we haven’t got any kids…’

The receptionist looks confused, as though this doesn’t quite compute: ‘The walls are decorated with butterflies?’ 4

I fully expect him to offer us a goblet of unicorn tears next and so try to dissuade him gently: ‘Really, it sounds lovely, but we just don’t need anything quite so … fancy. Isn’t there anything else available?’

He frowns and taps away at his keyboard for a few moments before looking up and resuming a wide smile: ‘I can offer you The Pirate Suite?’

We spend the first night in our new homeland sleeping beneath a giant Jolly Roger. There is a dressing-up box and all manner of parrot and pieces-of-eight paraphernalia. In the morning, Lego Man emerges from the bathroom wearing an eye patch. But things seem better by daylight. They always do. We draw the curtains to reveal a bright, white new world and blink several times to take it all in. Fortified by an impressive breakfast buffet, which includes our first encounter with the country’s famed pickled herring, we feel ready to begin ticking off the various items of ‘life admin’ necessary for starting over in a new country. And then we step outside.

The snow has shifted up a gear, from gentle, Richard Curtis film-style flakes into snow-globe-being-shaken-vigorously-by-angry-toddler territory. The sky empties fast, dumping its load with urgency from all directions now. So we go back inside, put on every item of clothing we have, then emerge an hour later, looking like Michelin Men but better prepared to start the day.

In the hire car, I try to remember that the gear stick isn’t on my left and that I need to drive on the right, while Lego Man reads from the to-do list that his new HR manager has 5thoughtfully emailed over. This comprehensive document extends to an alarming ten pages and is, we are informed, only ‘phase one’.

‘First off,’ Lego Man announces, ‘we need identity cards – otherwise we don’t technically exist here.’

It turns out that the ID card scheme that Brits railed against for years before it was scrapped in 2010 has long been integral to Danish life. Since 1968, everyone has been recorded in a Central Population Register (CPR) and given a unique number, made up of their date of birth followed by four digits that end in an even number if you’re female and an odd number if you’re male. The number is printed on a yellow plastic card, which is ‘TO BE CARRIED AT ALL TIMES’ (the HR man has emailed in shouty capitals). Our unique numbers are needed for everything, from opening a bank account and healthcare to renting a property and even borrowing books from a library. (If only we could read books in Danish. Or knew where the library was. Or the word for ‘library’ in Danish.) I will even have a barcode that can be scanned to reveal my entire medical history. It all sounds very efficient. And I’m sure it would be relatively straightforward, too, if only we knew what we were doing, or how to get to the bureau where we’re supposed to register. As it is, this task takes all morning. Even so, we count ourselves lucky – new arrivals from outside the EU have to wait months for their residency cards and these need renewing every couple of years. Being an immigrant is not for the admin-phobic.

Next, we need a bank account. A smart-looking man with closely cropped hair and distinctly Scandinavian-looking square glasses in the local (and only) bank greets us warmly 6and says that his name is ‘Alan’, before pointing to a name badge to reiterate this. I notice that it’s ‘Allan’ with two ‘l’s, Danish-style. Allan with two ‘l’s tells us that he will be managing our account. Then he pours us coffee and offers us our pick from a box of chocolates. I’m just thinking how civilised and friendly this is in comparison with my dealings with banks back home when he says:

‘So, it looks like you have no money in Denmark?’

‘No, we only arrived yesterday,’ Lego Man explains. ‘We haven’t started work yet, but here’s my contract, my salary agreement and details of when I’ll get paid, see?’ He hands over our documents and Allan studies them closely.

‘Well,’ he concedes eventually, ‘I will give you a Dankort.’

‘Great, thanks! What is that?’ I ask.

‘It’s the national debit card of Denmark, for when you have some money. But of course it will only work in Denmark. And there can be no overdraft. And no credit card.’

‘No credit card?’

I’ve been batting off credit card offers in the UK since leaving school without a penny to my name. Global financial crisis or otherwise, credit cards have been akin to a basic human right for my generation. Putting it on plastic is a way of life. And now we’re being made to go cold-hard-credit-card-turkey?

‘No credit card,’ Allan restates, simply. ‘But you can withdraw cash, when you have it,’ he adds generously, ‘with this!’ He brandishes a rudimentary-looking savings account card.

Cash! I haven’t carried actual money since 2004. I’m 7like the Queen, only with a blue NatWest card and a penchant for impractical shoes. And now I’m going to have to operate in a cash-only world, with funny green, pink and purple notes that look like Monopoly money and strange silver coins that have holes in the middle? I don’t even know the Danish numbers yet! But Allan with two ‘l’s will not be moved.

‘With this card,’ (he waggles the plastic rectangle in front of us as though we should be very grateful he’s trusted us with anything at all) ‘you can log on to internet banking and get access to government websites.’ This sounds very high-powered. I wonder whether we’re talking CIA-Snowden-style info before Allan clarifies: ‘You know, to pay bills, things like that.’

Bank account in place (if empty) we can now officially begin looking for somewhere to rent. A relocation agent will be assisting us with our search but with a few hours to kill until we meet her, Lego Man suggests a recce around the nearest normal-sized town in case we decide that toy town isn’t for us.

Driving through Billund’s uninspiring streets of identikit bungalows, like some sort of play-inspired military base, I have already decided that toy town is not for us and so I’m hoping that the next place is an improvement. Things start encouragingly enough with attractive red-brick mansion blocks and municipal buildings, cobbled streets and interesting boutiques nestled between big high street stalwarts. The place looks a lot like a Scandi version of Guildford. But after a couple of laps of the ‘high street’, we’re left wondering whether perhaps there’s been some sort of nuclear 8apocalypse that’s only been communicated in Danish, meaning we’ve missed it.

‘We haven’t seen a single soul for…’ I consult my watch, ‘…twenty minutes.’

‘Is that right?’

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘In fact, the only things resembling human forms we’ve encountered are the life-size sculptures of naked bodies with horses’ and cats’ heads on them in that weird water feature a few streets back.’

‘The sort of porny pony version of Anita Ekberg in the Trevi fountain in the “town centre”?’ Lego Man makes a bunny ears gesture to indicate that he didn’t think much of the thriving metropolis.

‘Yep. That’s the one. The porny pony and the cats with boobs.’

‘Huh.’

This particular statue, we later learn, was intended as a tribute to Franz Kafka. He must be very proud, I think. We pass more shops that are all either closed or empty and houses that look unoccupied save for the dim flicker of candlelight burning from within.

‘This isn’t normal, right? I mean, where is everyone?’ I ask.

‘I … don’t know…’

I check the news on my phone: there have been no atomic incidents. World War III has not been declared, nor has any alarming viral outbreak been announced. The threat of imminent death having been ruled out, Lego Man suggests going for a drink to wait for the place to warm up. Only we can’t find a pub. Or a bar. Or anywhere that looks 9a) open and b) isn’t McDonalds or a kebab joint. Eventually, we locate a bakery that also sells coffee and I suggest to Lego Man that we order ‘one of everything’, in the hope that carbohydrates might cheer us up.

The place is empty, so we stand expectantly, waiting to be served. But the woman behind the counter remains expressionless.

‘Hi!’ I try, but she averts her eyes and busies herself rearranging a crate of buns. Lego Man tries pointing at various things with his eyebrows raised (the universal symbol for ‘please may I have one of those?’) until eventually the woman cracks and makes eye contact. We smile. She does not. Instead, she points to an LED display above her head that shows the number 137. Then she points at a delicounter-style ticket dispenser behind us and says something we don’t understand in Danish.

I’m not trying to buy ham from a butcher in the 1980s. I just want buns. From her. In an empty shop. Is she seriously telling me that I have to get a ticket? Or that 136 people have already passed through here today? Or that there even are 136 people in this town?

Bakery woman has now folded her arms resolutely, as if to say: ‘Play by the rules or no buttery pastry goodness for you.’ Knowing when I’m beaten, I turn around, take three paces to my right, extract a small, white ticket with the number ‘137’ on it from the machine, then walk back. The woman nods, takes my ticket, and uncrosses her arms to indicate that normal service can commence.

Once we’ve ordered, Lego Man gets a call from his overly keen HR liaison officer. He steps outside to talk, away from 10the racket of the milk frother, and I pick a table for us and our gluttonous selection of pastries. ‘Don’t start without me,’ he says sternly, hand over the mouthpiece.

His caution isn’t unfounded. I have form in this area and can’t be trusted within a hundred-metre radius of a cake. I can feel my stomach knotting with anticipation and don’t know how I’m going to keep from taking a bite until Lego Man is back. To distract myself, I Google ‘new country, Denmark, culture shock’ on my phone and drink coffee furiously.

I learn that Danes drink the most coffee in Europe, as well as consuming eleven litres of pure alcohol per person per year. Maybe we’ll fit in just fine after all. More helpfully, I also come across the website of cultural integration coach Pernille Chaggar. Deciding that a cultural integration coach is just what I need to start my year of living Danishly and buoyed up by a second cup of strong Danish coffee, I call and ask Pernille to take part in my happiness project. She kindly agrees – and doesn’t make me take a ticket to call back later.

After expressing surprise that we’ve moved from London to rural Jutland, she offers her condolences that we’ve done so in January.

‘Arriving in winter can be really hard for outsiders,’ she tells me. ‘It’s a private, family time in Denmark and everyone hides behind their front doors. Danes are very wrapped up – literally and metaphorically – from November until February, so don’t be surprised if you don’t see many people out and about, especially in rural areas.’

Marvellous.

‘So, where are they all? What’s everyone doing?’11

‘They’re getting hygge,’ she tells me, making a noise that sounds a little like she has something stuck in her throat.

‘Sorry, what?’

‘Hygge. It’s a Danish thing.’

‘What does it mean?’

‘It’s hard to explain, it’s just something that all Danes know about. It’s like having a cosy time.’

This doesn’t help much.

‘Is it a verb? Or an adjective?’

‘It can be both,’ says Pernille. ‘Staying home and having a cosy, candlelit time is hygge.’ I tell her about the deserted streets and seeing candles burning in many of the windows we passed and Pernille repeats that this is because everyone’s at home, ‘getting hygge’. Candlelight is apparently a key component and Danes burn the highest number of candles per head than anywhere else in the world. ‘But really, hygge is more of a concept. Bakeries are hygge—’ Bingo! I think, looking at the spread of pastry goodness in front of me. ‘—and dinner with friends is hygge. You can have a ‘hygge’ time. And there’s often alcohol involved—’

‘—Oh, good…’

‘Hygge is also linked to the weather and food. When it’s bad weather outside you get cosy indoors with good food and good lighting and good drinks. In the UK, you have pubs where you can meet and socialise. In Denmark we do it at home with friends and family.’

I tell her I haven’t got a home here yet, nor any friends. And unless something radical happens and my mother decides that Berkshire is overrated, I’m unlikely to have family here any time soon either.12

‘So how can a new arrival get hygge, Danish-style?’

‘You can’t.’

‘Oh.’

‘It’s impossible,’ she says. I’m just preparing to wallow in despair and call the whole thing off when Pernille corrects herself, conceding that it ‘might’ in fact be feasible if I’m willing to work at it. ‘Getting hygge for a non-Dane is quite a journey. Australians and Brits and Americans are more used to immigrants and better at being open to new people and starting up conversations. We Danes aren’t great at small talk. We just tend to hole up for winter,’ she goes on, before offering a glimmer of hope. ‘But it gets better in the spring.’

‘Right. And when does spring start here?’

‘Officially? March. But really, May.’

Brilliant. ‘Right. And, taking all this into account,’ I can’t help asking after the bleak portrait she’s just painted, ‘what do you think about all these studies that say Denmark is the happiest country in the world? Are you happy?’

‘Happy?’ She sounds sceptical and I think she’s going to tell me the whole ‘happy Danes’ thing’s been blown out of all proportion until she answers: ‘I’d say I’m a ten out of ten. Danish culture is really great for kids. Best in the world. I can’t think of anywhere better to be raising my family. Do you have kids?’

‘No.’

‘Oh,’ she says in a voice that implies, ‘in that case, you’re really screwed…’ before adding: ‘Well, good luck with the hygge!’

‘Thanks.’

13Lego Man returns from outside, lips now a blueish hue and shivering slightly. He announces that the toymaker and his elves are all ready for their new arrival and that he’ll start work as planned in a week and a half, once we’ve settled in. I tell him that this last part may not be as easy as it sounds and relay my conversation with Pernille.

‘Interesting,’ he says, when I’ve downloaded. We sit in silence for a bit, staring at the fully loaded plate of glistening carbs in front of us. After a few moments, Lego Man raises himself up, removes his glasses and places them on the table, stoically. Then clears his throat, as though he’s about to say something of great import.

‘What do you think,’ he starts, ‘Danes call their pastries?’ He holds one up for inspection.

‘Sorry?’

‘Well, they can’t call them “Danishes” can they?’

‘Good point.’

In the great tradition of British repression, we ignore the potential futility and loneliness of our new existence and seize on this new topic with enthusiasm. Lego Man gets Googling and I crack open the spine of our sole guidebook in search of insight.

‘Ooh, look!’ I point, ‘apparently, they’re known as “wienerbrød” or “Vienna bread” after a strike by Danish bakers when employers hired in some Austrians, who, as it turned out, made exceedingly good cakes,’ I paraphrase. ‘Then when the pastry travelled to America—’

‘—How?’

‘What?’

‘How did it travel?’ 14

‘I don’t know – by ship. With its own special pastry passport. Anyway, when it made it to the US, it was referred to as a “Danish” and the name stuck.’

I don’t read any more as I realise that Lego Man has been using the opportunity to get a head start on stuffing his face and I don’t want to miss out.

‘This one’s a “kanelsnegle