Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

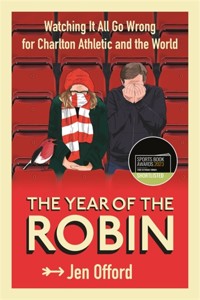

SHORTLISTED IN THE SUNDAY TIMES SPORTS BOOK AWARDS 2023 FOR NEW FEMALE SPORTS WRITING 'Jen has captured the human (and humorous) side of following a football team. A compelling story hilariously told' Sara Pascoe 'From family to football, Jen Offord has captured something we can all relate to. Funny and heartbreaking in equal measure. A must read.' Cariad Lloyd 'Hilarious and moving in equal parts' Carrie Dunn Jen Offord watches it all go wrong for Charlton Athletic and the world. When her beloved Charlton Athletic clinched promotion to The Championship in May 2019, sportswriter Jen Offord splashed out on season tickets for herself and her sceptical brother Michael, setting out to chronicle the south-east London outfit's first season back in the second tier of English football. But this season, more than any other before it, would be a game of two halves. A billionaire takeover backfired spectacularly; the team plummeted into the relegation zone just as Coronavirus swept in to suspend life as we know it. The Year of The Robin is a love letter to the power of football even when there is no football to actually watch, filled with wild characters searching for redemption and wrestling over issues of money, racism and mental health. A funny, sharp and a thought-provoking exploration of the idea of family in unprecedented times and season from which the world may never fully recover.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 470

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Lyra I love you even more than Alan Curbishley.

CONTENTS

The Warm-up

This is my story of the 2019/2020 season as experienced by me, my family, Charlton Athletic Football Club, and the world (in that order). As we went through everything those absolutely brutal months threw at us – boardroom meltdowns! a worldwide pandemic! an unexpected pregnancy! a nil-nil draw with Fulham! – I found myself wondering what it was that kept us going. Like, literally what kept us going back to those rainswept seats in the North Stand just to watch our team struggle through a midweek match in January – but also figuratively, what kept us going as a club and a community when everything seemed stacked against us (repeatedly)?

So I began to talk to the people who made the club what it was – the star striker with his knack for controversy, and the manager who’d turned everything around, but also the people in the background: the men who ran the club museum on barely a shoestring; the woman who looked after young players away from home for the first time; the community workers tirelessly tackling discrimination at grassroots level; the fans who had led protests and campaigns to save the club from oblivion more times than they cared to remember.

And maybe it was because I was sharing my season ticket seats with my brother, or maybe it was because I was in fact about to extend my own family, but everything I learned about CAFC that year told me something about family.

Everyone thinks their club is special, but Charlton Athletic actually IS special. You’ll see.

The Play-offs – or how my brother and I returned to the Charlton Athletic fold

In mid-March 2019, Charlton Athletic were fifth in the League One table. It was the third of four tiers of the English Football League, and one I hadn’t been able to muster much interest in since Charlton’s spiral into the abyss from the glory days of the Premier League.

There had been some near-misses in recent years as we’d yo-yoed in and out of the Championship. A few years ago, we’d even come close to challenging for a place back in the Premier League. It was the Charlton way to come close to moderate success yet still fail, and I’d not even cared very much about it when it had happened. The fact of the matter was, I’d not really cared much about what was going on at Charlton for a while now.

But there was something different about the club this year.

‘So Michael,’ I’d said to my older brother on the phone. ‘Do you want me to get us tickets to Charlton for your birthday, since there’s a chance we might actually win?’

‘Hmmmmmm,’ Michael had made a low noise, the implications of which were negative. ‘Thing is, sis, I’m boycotting them, so I can’t.’

Like many others, Michael was unhappy about Charlton’s owner, a Belgian billionaire by the name of Roland Duchatelet who bought the club in 2014. It was under Duchatelet that the tone of the club had changed to something not just unsettled and unhappy, but downright unsavoury as fans turned up to – curiously – lob packets of crisps onto the pitch, or just didn’t bother to turn up at all.

Duchatelet appeared to us to be running something of a rabid dictatorship at The Valley, enacted one bonkers press notice at a time. It’s impossible to talk about Charlton without talking about Roland and his reign of terror, but we’ll come back to him.

‘Really?’ I asked him. ‘Are you sure?’

‘Yep, sorry, sis, but I can’t go until he sells the club.’

Fast-forward a month, as we hurtled towards the end of the season and the very real possibility of a place in the play-offs, and Michael found himself in quite the moral maze.

‘So, I’ve been thinking,’ he told me one day, ‘that IF we make it to the play-offs …’

The emphasis had been on ‘if’, as with so many Charlton supporters, still refusing to allow himself to dare to dream, despite having been firmly rooted at the business end of the table for months.

‘… I’m not sure it would technically mean I’d broken my boycott, so long as you bought the tickets,’ he continued. It was classic Michael maths, I had to hand it to him.

‘So you know you said you would buy me tickets for my birthday …’ I absolutely had, and these would certainly be considerably more expensive than those if we made it that far.

‘What I’m saying is,’ he went on, ‘should you buy me tickets for the play-off final if we make it that far, I’d have no choice but to go.’

‘OK, Minks,’ I responded, addressing him by his family nickname, ‘Then I absolutely won’t buy you tickets to the playoff final *IF* we make it that far.’

‘Good stuff,’ he nodded. ‘Appreciate that.’

•

By the end of the season I was gripped with excitement.

Charlton had, beyond all hope and expectation, made it to the play-offs, having finished the season third.

Now just two matches from the crushing inevitability of failure on a televised stage for the first time in years, we were due to face Doncaster away, in the first leg of the semi-finals, and I was ready for it. In fact I was even prepared to be a big brave girl and watch it in the pub alone, had my mate Dave not stepped in.

‘I can’t let you do that,’ he’d said, himself a Manchester United supporter, concluding, ‘it’s too tragic.’

•

On 12 May, Charlton beat Doncaster 2-1 in the first televised match I’d seen them play in since 2006. I had texted my brother some waffle in the early hours of the morning about being nervous. He understood the nerves, he said.

The pub had been most amenable to switching the channel from the Old Firm match that had been playing out. After all, this was London. Though the barman had initially been sceptical.

‘Is that even on telly?’ he asked, a quizzical expression on his face.

‘It’s Sky Sports blah, at blah,’ I told him firmly, feeling like

J.R. Hartley himself.

‘Yeeeeaaaaaah,’ the barman started, in a tone that was familiar to me – it was the same tone used by anyone reacting to the news that I support Charlton Athletic: ‘I like Charlton.’

‘Got a mate actually,’ he continued. ‘Used to play in Charlton’s youth academy.’ It was a long-held theory of mine that everyone knew someone who either had played in Charlton’s youth academy, or at the very least nearly played in it.

‘The thing you forget about Charlton,’ I began, ‘is that a lot of big names have come from their academy,’ citing the three names I could immediately recall, vowing to get better pub chat.

After the victory I called Michael to discuss the match.

‘For all his failings,’ Michael commented wistfully, ‘you can’t deny Lee Bowyer has brought the club together again,’ before adding something negative about the probability of getting tickets if we got to the final.

I silently rolled my eyes at him for the first of many times over the next couple of weeks.

•

A week later and I was at dinner with a group of friends. The second leg of the play-off semi-final was under way and it’s fair to say I was distracted from my dinner. It was a long-standing commitment that I had felt unable to un-make, given that the majority of the party members had arranged a night off from mothering for the sake of our meal.

‘Does anyone actually give a fuck about Charlton Athletic?’ one friend asked me, as I checked my phone for the 50th time.

I was confused, since my dedication to SE7 was well documented.

‘Oh,’ she said as I justified my distraction, ‘I sort of thought that was a joke.’

Dinner finally came to an end and we made our way to a pub, one less amenable to showing third tier English football, and so I brought up the club’s Twitter feed on my phone as my fellow drinkers chatted amongst themselves, knowing now that they had lost me. Somehow – SOMEHOW – having won the first leg against Doncaster, we had found ourselves level pegging against the visitors, after extra time. Penalties it was.

Penalties. Well, that was that, then. Brought down by fucking Doncaster before we’d even had the chance to waste money on tickets to see them lose at the home of English football, Wembley Stadium. Brought down by the team who’d finished in sixth place to our third.

‘Fuuuuuuuuuuuucking hell,’ I texted Michael.

‘What a nightmare!’ he responded.

Or not.

Oh ye of little faith. And indeed, I had forgotten that my little club had some pedigree in the business of penalties in the play-offs, having beaten Sunderland via the very same arbitrary mechanism in the play-off final of 1998 – widely regarded as one of the greatest play-off finals of all time.

Unbelievably luck was to be on our side again that fateful Friday night, as I waited with bated breath for the Twitter feed to update. Suddenly images of euphoric fans invading the pitch at The Valley began to flood my timeline as Charlton beat Doncaster 3-2 on penalties.

As the news came in that old foes Sunderland had beaten Portsmouth, and Charlton would face them for a second time in a play-off final, Michael messaged me again.

‘Got to get tickets! I’ll be checking for sales announcements pretty much every 30 secs from now on!’

Warmed by victory and more than a few glasses of wine, I sat grinning on the number 149 as I travelled through the drizzle on Kingsland Road, not even caring if anyone could hear that I was listening to ‘Bamboleo’ by the Gipsy Kings, in celebration.

We were going to Wembley – for the first time in 21 years.

•

The day of the play-offs arrived, and I met my brother, his girlfriend Kerry and childhood friend Jamie at a pub near Liverpool Street station. I was hung-over and late, and they’d somehow managed to sink two pints before I arrived.

With Michael still technically boycotting the club and busy ‘working’ on the morning tickets went on general sale, I had been on ticket-buying duties. In the days prior to this, I had been receiving almost hourly texts from my brother imparting either some sort of negative energy about the improbability of actually securing the tickets, or tactical wisdom on how to ensure that we did.

‘Don’t think it will be easy,’ he told me.

‘Approx 38k tickets each, 25k at The Valley for the semis. Each of those can get up to six tickets … who knows …’

‘Loads of people rushing to get tickets tomorrow … Crack on as close to 9am as you can …’

The burden of being on ticket-buying duties had actually led to a sleepless night in the run-up to the event, but I had done it. And I had racked up some major sister points, a delighted Michael conceded.

•

The night before the play-offs themselves I had been at a friend’s bar, close to home in Hackney, chatting excitedly about the upcoming clash.

‘Oh, right,’ he said. ‘My friend Mike’s going to that as well,’ introducing me to a member of his staff.

Mike and I regarded each other with caution, before a pathetically British, good-natured chat ensued, neither party prepared to slag off the other, or accept the possibility of victory, both so desperately wanting it.

Mike, who I thought was probably about ten years older than me, had been at the play-off final in 1998 and witnessed the heroics of hat-trick-scoring Clive Mendonca, a Mackem himself, now a Charlton Athletic legend.

I had been just fifteen years old at the time, and not even able to watch the match in the pub with my brother, but Mike spoke with genuine warmth of a great day and a wonderful match. He must surely have thought this time would be his time?

‘It was such a great match – such a friendly atmosphere,’ he told me. ‘Let’s hope for more of the same tomorrow.’

Indeed, I thought, as we shook hands and finally went our separate ways.

Back in the pub, there was a sense of foreboding in the air as it occurred to me, and not for the first time, that there was a very real possibility we would not win this.

I had never been to a Charlton match and seen them win, and though I knew realistically this was not my fault, I had wondered if I was a football jinx. At almost any time I nailed my colours to the mast on Twitter, any team I affiliated myself to would promptly turn their fortunes around to lose. And let’s face it, if ever a team were capable of this, it was Charlton.

There were a few other football fans in the pub, and Michael quickly sought out one with a North East accent, sitting alone, who he offered to buy a pint for. I found his sportsmanlike gesture both classy and heart-warming. He was a good lad really, my brother.

Alas, he explained in a hushed tone, he had seen some Sunderland fans on the train to London, helping an old lady with her suitcase. Buying a Sunderland fan a pint, he thought, would redress the balance of karma in Charlton’s favour.

Shortly after the transaction was made, it transpired the man was in fact a Newcastle fan, on his way to Stansted airport for a flight, and his presence in London completely unrelated to the game. If anything, I assumed he would probably have preferred a Charlton win, but hoped karma would appreciate the gesture, nonetheless.

•

It was a warm day in late May, and I had never seen a Tube carriage so densely populated with sunburned faces, as our Metropolitan line train to Wembley Park filled up at Baker Street. Standing room only for those now piling on, red shirts filled the carriage, clashing wildly with the various hues of pink.

Sunderland fans to our right, Charlton fans to our left, the chanting started between the two. One woman took her phone out to film the two tribes as they – in what seemed a relatively good-natured battle – began to shout at one another from across the Tube.

‘We’ve seen you cry on Netflix, we’ve seen you cry on Netflix! La la la la, la la la la!’ began the Charlton fans, referencing a now infamous documentary supposed to chart the phoenix-like rise of Sunderland back into the Premier League after their recent descent, but ultimately telling a very different story.

The Tube shuddered with the weight of the men at either end, stomping their feet with excitement as the cries continued: ‘Lyle Taylor, baby! Lyle Taylor whooooooooaaaah!’, to the tune of The Human League’s ‘Don’t You Want Me’.

The young couple with a small child sitting next to me seemed to take it in their stride as the train erupted into song again: ‘And now we’ve got Lee Bowyer, we’re fucking dynamite!’

•

As we arrived at Wembley Park, all I could see stretched ahead of me on Wembley Way was a sea of red and white – a sprawling mass of synthetic red fabric pulled taut across rotund bellies. Charlton would play in their home colours, as the higher placed team at the end of the season.

There were older men, in their fifties, sixties and seventies, and plenty of people around my own age in their mid-thirties. But also children, teenage boys, presumably tied to this unglamorous South East London club by local connections, as I had been. There were young girls with their dads, perhaps drawn in by the recent groundswell of support for women’s football. There were more women than I had expected, which I discovered with some regret as I joined the queue for the ladies’.

It was good-natured – joyous even – as we all united with the hope of winning. It was the hope of your team winning rather than the other losing. There were no London faces here, avoiding eye contact or visibly balking at the prospect of speaking to a stranger, but you couldn’t escape the lingering tension of knowing just shy of 40,000 people would leave the stadium in a couple of hours’ time, without that feeling of hope. My stomach knotted at the prospect of being one of them.

In our seats right up in the gods of Wembley Stadium, we watched on. We hadn’t quite arrived in time to neck another pint before kick-off, and I couldn’t have felt more sober compared to the five or six men in the row behind us. Without exception, they appeared the absolute epitome of anything bad you had ever thought about football fans, their faces an extraordinary shade of puce, slurring their words and jostling into the back of our seats as the excitement began to build.

‘Wonderful,’ I thought to myself as I grimaced at Kerry.

The stadium roared as the match got under way, in the anticlimactic way that all football matches begin. Having watched a lot of football by now, I had concluded everyone was a bit shit in that unremarkable early stage of a game, as teams find their feet and seek to establish the dynamics of their impending power play.

I was unprepared for just how shit a team could be.

Disaster struck in the fifth minute as Charlton defender Naby Sarr passed the ball back to the keeper Dillon Phillips. It appeared to unfold in slow motion as the ball rolled – and not at great speed, it must be said – towards Phillips, a little way out of his goal area. As we watched, it didn’t even occur to us that there could possibly be anything to worry about.

‘It’s OK, he’s going to get that,’ I began to think over the few seconds that seemed to stretch out for an eternity. ‘He’ll get that,’ I repeated to myself.

‘He’s going to …’ Somehow, he didn’t. There was an audible gasp as the ball rolled across the line and into the goal. Charlton were 1-0 down after five minutes thanks to the stinkiest of all of the stinkers.

Sharing my match-day experience via Twitter, I typed: ‘Shitting hell.’

Dillon Phillips echoed the reaction of every Charlton fan in that stadium as he brought his brightly coloured, gloved hands to his face, and closed his eyes.

‘You still have time!’ one of my followers piped up.

I wanted to go home. That was it, I thought to myself. How could we come back from that?

There was silence, for a time, even the mob behind us seemed to say nothing, but Phillips made a decent save shortly thereafter, and we sighed collectively in relief.

‘Thank Christ for that,’ Michael said. ‘He’s got the home crowd behind him now, but they’re going to give him so much shit at the away end in the second half – thank God he made that save now.’

And Michael was right; it seemed to be just enough to give them that edge of confidence – perhaps, perhaps, they might be able to do something with this game after all.

After a cagey period, it was of course Lyle Taylor baby himself who made the low cross to Ben Purrington to tap the ball in the net in the 35th minute, and at last we were back in the game. The crowd roared with excitement, and the men behind us screamed.

By this point, the only discernible words coming from our friends were various slang words for intimate parts of the female anatomy. Everything else was just a long, scratchy rasp of vowels.

‘ooooooooooooooooooooooo scorrrrrrrrrrrred?’ one of them screamed.

It went on for the best part of the rest of the half, oblivious to the ball icon sitting next to Purrington’s name on the giant screens.

‘Yooooooouuuuuu fahhhhhhhhhkin puuuussssssssy!’ one of them rasped, looking perilously close to death as he did so, the puce of his face deepening to a sort of aubergine hue. He was also apparently unaware that it was in fact one of our own players on the ball.

One of them tipped his bucket of popcorn on top of his head, exclaiming the act was in tribute to Lyle Taylor’s bleached curly hair, and everyone within approximately ten people of said man visibly winced, not for the first time – was that … was that a bit racist?

As the half-time whistle blew, I was relieved when after falling into the back of Michael for the second time, they shuffled off to the bar.

‘I wonder,’ pondered Jamie, referring to our fellow supporters, ‘what do you think they actually do? You know, in their day-to-day lives? Like, what do you think their jobs are?’

I had noticed a couple of obvious weaknesses in our game, I told Michael and Jamie as Kerry went to the loo. We weren’t very good at set pieces, I commented, adding: ‘Or keeping the ball in – they’re quite bad at keeping the ball on the pitch. It’s almost as if they don’t really understand how big the pitch is?’ It was a big pitch, after all.

Still, there were promising elements to the game and hope was still alive; they were nothing if not doggedly determined.

The match went on. After some decent chances in the first half, Charlton seemed revived, but the break would not come.

The atmosphere grew more tense and the men behind us more drunk, by this point having twice lurched into the back of me as well. Ordinarily, I would have been the kind of person to get a bit lairy about such things, but sensing these might not be the most reasonable characters, I bit my tongue, not wanting Michael and Jamie to have to deal with the fallout.

‘Please be careful,’ I hissed.

‘Aaaaahhhh, sorrrrrrrrrrry, love,’ he slurred, trying to hug me, which was almost as offensive as the barging, to be honest.

As we approached the end of the second half, I felt I wouldn’t be able to bear another 30 minutes of the tension, should the match go to extra time. I had already clapped my hands to the extent that I could see purple bruises swelling under the surface of my skin.

‘How on earth do you clap?’ Jamie asked me. Aggressively, apparently.

When the giant screens announced four minutes of stoppage time, my heart sank. It was enough time for one team to score, but in all probability, not both teams.

We watched on, teeth gritted, jaws jutting, praying just to stay in the game. We could not have predicted what was to follow.

Suddenly all bodies were in front of the Sunderland goal. There was a shot on goal and we groaned as it deflected, but in what would be almost the last kick of the game, it was leapt upon by captain Patrick Bauer – and somehow, magically, we had taken the lead.

The crowd erupted, as Lee Bowyer began to celebrate and players ran off the bench. Blow the whistle. Blow the whistle.

The whistle blew just seconds later.

The noise in the stadium was deafening as the players ran up and down the pitch, sliding across it on their knees. Preparations began for the trophy presentation and the crowd roared. I felt a lump rise in the back of my throat as Bowyer embraced Charlton legend Alan Curbishley – the man Bowyer had played under himself as a youngster at the club.

My phone began to vibrate as friends sent congratulatory messages – they understood what it meant.

I looked at the giant screens and they declared ‘Charlton Athletic: WINNERS!’ and I took in the atmosphere around me. To my right was just a barren wasteland of empty seats – I had never seen 38,000 people evaporate so quickly. But here, in the thick of it we were jumping up and down, singing, shouting, screaming even – a football match had never meant so much to me.

In that moment I remembered the day – it was the fifteen-year anniversary of the death of our older brother, Stephen, and if the tears weren’t there already, they began to prick painfully at my eyes. Through the tears, in the corner of my right eye, I could see Michael also looked a little choked, and I wondered if the same thought had occurred to him.

I remembered how it had been the Euros in 2004, shortly after Stephen died. I remembered going back to Sussex University and watching England play Portugal in that tournament, the penalties, and the unbearable prospect of failure.

I remembered silently telling myself as I left the bar unable to watch those penalties, and in the way that one makes arbitrary rules or judgements in the face of losing all control over their own life, that if England could just score those goals, it would mean something. It would mean that Stephen was somewhere, and I genuinely believed if they could just win the game, it would in some small way be indicative of some sort of higher power. But England did not score those goals. It was stupid, superstitious – I wasn’t a superstitious person and I didn’t even believe in any specific higher power, but it stayed with me, and was always in the back of my mind during important international games.

Stephen hadn’t actually supported Charlton – somewhat contentiously, he had been a West Ham fan – but he loved football more than any of us. It would have been a match he almost certainly would have come to, and a victory he could easily have got behind, for his siblings and because Charlton were the kind of club you could get behind. I began to sob quietly as finally, a game had actually meant something, and I could allow myself for that brief moment in time to believe this victory was spiritual, even.

It was spiritual, at least, until two of the puce-coloured men from the row above fell on top of me.

In the Beginning

I first went to see Charlton Athletic play in 2002. I cannot remember who we were playing against, if I’m entirely honest, but looking at the fixtures list now, I feel it could have been Southampton. It was late in the Premier League season, against a team you could easily get tickets for, it had been at The Valley, and we had drawn. It had been underwhelming and exhilarating all at the same time, to a large extent because earning the right to be there in the first place had been hard won.

Michael – the only other person I knew who wanted to see Charlton Athletic play – had been reluctant to allow me to go with him. His mate Ben had sort of adopted Charlton as his team, so he didn’t need my company and, he said, I would ‘ask too many questions’.

Looking back on it now, and knowing Michael not to be, nor having ever been a misogynist, I wonder if this stance might have been more to do with feeling Charlton was ‘his thing’. We had always got on well, but I had muscled my way into almost every friendship group he’d ever had, and perhaps he’d just wanted something for himself. As much as he had pissed me off at the time, perhaps retrospectively I could have been a little more sympathetic.

The fateful day had come about by unfortunate accident. It had been Michael’s birthday in late March, and back then – before he was ‘boycotting’ the club, he had always wanted Charlton tickets as presents for birthdays and Christmases. Knowing that our mum had done as asked and procured these, and it being his 21st, I had wanted to buy him something special – an experience he could remember, not just a CD or DVD as was customary.

So I bought him two tickets for the London Eye.

Yes, with hindsight it was perhaps not a great present, but there was a method to my madness – why not have a lovely day out in London when he went to see Charlton? The Eye was relatively new at the time, so who wouldn’t want to check it out?

‘I hate London and I hate heights,’ he told me as he stared bewildered by the contents of the envelope I had handed him.

He had never told me he hated either, but the disdain was nonetheless palpable and I was crestfallen. I had genuinely considered it a thoughtful and inspired gift.

To this day, I don’t know what happened next – whether he took the decision himself, or whether he had been leaned upon by our mum, unimpressed by his reaction. Whatever inspired the gesture, in the week that followed, Michael apologised unreservedly and – to show he meant it – offered to take me with him to both the Charlton match and the London Eye, and I had enthusiastically accepted. After all, who wouldn’t want to go on the London Eye?

We would both travel from our respective universities – his in Canterbury and mine just outside Brighton – to meet on the day. The London Eye first, then to The Valley.

The night before I had been mortally drunk and snogged a boy in the campus club, The Hot House. He was the cock of the Sussex University walk and had told me with an air of superiority that he was invited to Dean Gaffney’s birthday party – and that his brother played for Crystal Palace’s youth academy. He wasn’t even lying as there had been a T4 documentary series at the time, The Players, and sure enough the brother had been on it.

‘Urgh,’ I scoffed, keen to put him in his place while establishing myself as a woman of niche footballing tastes. ‘I don’t even like Crystal Palace. I support Charlton – I’m going to a match tomorrow.’

I was excited and proud to be attending my first football match, and I wanted everyone to know about it.

In the event, when I arrived in London I had been desperately hung-over, having sobered up somewhat on the journey into Victoria.

‘Oh look,’ Michael said, his face pressed against the glass of the capsule, while I sat with my head in my hands as we reached the Eye’s zenith. ‘You can see the Tower of London.’

We ended up having a good day, although perhaps Michael’s had been slightly better than mine, but this wasn’t just my first Charlton match – it was my first football match outside of the ones I’d watched my brothers play at school.

The Valley seemed huge with its capacity of 27,000, and the atmosphere had been epic. We had chuckled along with the young family next to us, as a man effed and blinded, before realising his error and clasping his hand to his mouth in horror. However, it never seemed scary or intimidating in the way that one imagines a football match might be – it had always seemed like a warm place to be.

Desperate to be allowed back, I bit my tongue throughout, and ultimately Michael had to concede I had not asked too many questions. One or two, he thought (lies), but not an untenable amount. Perhaps he would extend this privilege to me again one day, after all.

We did in fact return to The Valley together several times, and I cannot remember who we played on any occasion, apart from Arsenal in October 2003, although we had not won any of the matches we had been to together.

I mostly remember the Arsenal match because it was the era of the ‘Va-va-voom’ Renault adverts and Thierry Henry had been playing. Incredibly, we ended up with pitchside tickets. Michael had been quite reasonable, as my commentary consisted largely of things like ‘Get off him!’ when someone pulled Henry’s shirt.

‘This is the closest you will ever legally be to Thierry Henry,’ he had shrugged with what seemed a genuine degree of understanding.

We didn’t win, but we didn’t lose. It was a big match, and Paolo Di Canio had scored an audacious penalty for us. It ended 1-1 and Henry had scored the Arsenal goal, so there was a lot to be happy about, from my perspective.

•

In the weeks that followed our victory in the play-off final, I became increasingly interested in the fate of my team, again. I wouldn’t say I was a fair-weather fan, rather that my love of Charlton had been reignited, and that for the first time in a long time, there had been a positive vibe about the club.

‘I think we should get season tickets,’ I told Michael, upon learning that the cheapest tickets only cost £220.

Michael took a more cautious approach. Not living in London himself, he wasn’t sure he’d be able to make the pilgrimage often enough to warrant the expense. He was also concerned about the likely impact of promotion on the squad, and the possibility of haemorrhaging our good players. Our budget was going to be tiny and it might not be the great fun I was imagining, but my head was already full of Leicester City’s 2016 season, great sporting triumphs and the possibility – no matter how small – of a return to the Premier League glory days.

I mulled it over, despite his reluctance, and found myself three pints and no dinner down on a date, a week or so later, explaining my dilemma.

‘You’ll see some good football in the Championship,’ my date had reasoned.

By the time I got home I was suitably merry enough to whip out my credit card and make the purchase, with really very little idea about what I was doing in terms of seat selection, but I picked two, signing one over to my brother.

I broke the news to Michael as he received a surprise email from Charlton congratulating him on becoming a season ticket holder. I half expected him to be a bit annoyed that I had effectively gone against his wishes, so I played it down and stressed that there was no pressure on him to make all the matches, I’d take friends with me, and so on, but he was about as happy as I’d ever seen him.

‘Honestly, sis, this is the nicest thing anyone has ever done for me,’ he said. ‘I’m actually crying a bit.’

His reaction, in turn, made me a little weepy myself. Buying him that season ticket, and the absolutely first-class sistering on my part, became my proudest moment in life.

The CAFC Museum

Over that summer – those heady weeks between winning the play-offs and starting our first Championship season – I thought about that funny little corner of London at great length. I had spent the first six years of my life there, and could remember our old house on Delafield Road – almost directly opposite Floyd Road and just a stone’s throw from The Valley.

It was the house where family legend had it that Michael had coined the term ‘gommow’ for trains. Apparently this had come about because every time my dad had exclaimed at his tiny son, ‘Look, a train!’ pointing at the tracks at the end of our garden, Michael would react at just the point Dad sighed, ‘Ahhh, it’s gone now.’ Until one day he had shrieked ‘GOMMOW! GOMMOW!’ as he finally got a glance of the shuddering beast.

I could remember Fossdene Primary School, where I had attended nursery and reception infants’ class; our neighbours Lou and Bill; and a cat called Sheba who lived on the other side and was said to have been about eighteen years old when we lived there. I had a sense retrospectively that a lot of the people on our road were working class, but these were not really the things a five-year-old thought very much about.

Though I had been to The Valley a fair bit, I’d not wandered around Charlton for years and years, but I got the feeling from things people said to me that the area was ‘a bit Brexity’, and largely untouched by the gentrification many other formerly working-class areas of London had experienced. Indeed, a quick Google search revealed that a five-bedroom house in Stoke Newington was apparently worth almost double that of its Charlton equivalent.

‘Go and look at the Village,’ my mum had suggested when I’d asked her about it, referring to what must have been considered the more ‘upmarket’ end of town. ‘At the top of Charlton Church Lane – that’s probably where you’ll find your artisanal breads.’

In a bid to immerse myself back in all things SE7, I was keen to have a nose around the land from which we hailed, and to visit the Charlton Athletic museum – a place I had only recently discovered the existence of, nestled in a back room within the grounds of The Valley. The museum only opened on Saturday match days for a couple of hours, and one Friday afternoon each month.

On this drizzly Friday, I found myself wandering past the usual turnstiles and the photos of Charlton greats adorning the outer walls of the North Stand. The heroes of 1998 were all there: Clive Mendonca brandishing his hands in what would later become the universal sign for ‘brrrrrrrrrrrrrap’; the resplendent Saša Ilić, who saved the match-winning penalty on that fateful day and was now apparently running a detox retreat in Montenegro; and of course a beaming Alan Curbishley himself (player, manager of fifteen years, and the legend who took us from the brink of bankruptcy to TWICE promoted to the Premier League) holding the trophy aloft – they were all here.

Following the car park round, I found a sign welcoming visitors to the museum which could be found, it said, on the third floor. Tentatively, I pressed a buzzer and awaited the response of a disembodied male voice, inviting me to take the lift inside.

I was welcomed by what would probably rather generously be called a mural, depicting the robin and knight mascots on a wall of a dark corridor. To my knowledge I had never been in this part of the stadium before. It didn’t look like anyone visited this part of the stadium too much, I thought, as I entered a lift straight from the 1980s, with its rudimentary operating mechanisms.

And then I was there, in the Charlton Athletic museum itself. A row of busts sporting Charlton shirts through the ages lined the long window running across the space. The old Woolwich Bank logos were emblazoned across the chests, as the sponsors of yesteryear, and the Viglen shirts I remembered from the late nineties – these were, according to Michael, akin to the old Arsenal JVC shirts in terms of iconic prestige. To my left, there was a table with a visitors’ book and a small box welcoming donations. Along the wall ran a timeline of the club’s history.

I was approached by a man who appeared exactly as I imagined an elder statesman of the game to look – perhaps it was the remnants of a summer tan, but he was not unlike Alan Curbishley, only with heavier eyebrows. His name was Nick.

I shook his hand and told him I was there to find out more about the history of my beloved club. He gestured around him, explaining some of the exhibits available. A small room playing a video about the club’s history and some books of newspaper cuttings; shirts, trophies and other paraphernalia.

They were not, he added, funded by the club, though former CEO Katrien Meire, Roland’s right-hand woman who had fallen foul of fans for, among many reasons, referring to them as ‘customers’ in ill-advised communications, had found this room for them.

‘Really, no money at all?’ I asked, surprised.

‘To be honest, it’s a blessing really,’ Nick told me with a wry look creeping across his face. ‘Means we don’t have to toe the party line too much.’

I liked Nick. He had the air of a man who had seen many Charlton games in his time – committed, wary, but ultimately not without a decent sense of humour.

I explained my interest in the club and the area, and how my naughty scamps for brothers had somehow sourced old programmes from the then-abandoned box office in our youth.

(To be honest, I had always questioned this story – Stephen having only himself been ten and Michael seven when we left, and I remembered we weren’t allowed to even play on the street, so there was no way they’d have been breaking into anything. I figured someone else’s big brother must have been the benefactor of these items. But for the purposes of my conversation with Nick, I went with the legend rather than the probable truth.)

‘Ah, then you probably need to talk to this guy,’ he told me, leading me further into the museum where another chap stood astride a large Sainsbury’s bag, full of books.

I was introduced to Alan – not Curbishley; turns out there are many Alans in the story of Charlton – a bespectacled man of robust build, who I judged to be probably in his sixties. He eyed me with some suspicion as we shook hands.

‘Oh, right,’ he said as I started to explain myself again, seemingly underwhelmed by my story.

‘Look, full disclosure, I’m a journalist,’ I told them, sensing their hackles immediately rise.

‘But not a horrible one,’ I added quickly. ‘I love Charlton and I’m just trying to find out a bit more about the history of the club for a project I’m working on.’

Their questions came in thick and fast – What kind of project? What did I want to know? What was I hoping to find? – as they began to gesture to cupboards and cupboards full of information.

This tiny museum was run by volunteers – just a bunch of old boys who loved the club and wanted to see out their retirement obtaining obscure artefacts like a court summons evicting travellers from an abandoned Valley in 1989 – and it was sitting on an absolute treasure trove of information about days gone by of the beautiful game. I was particularly interested in one seismic period in CAFC’s history – our time out of The Valley, and how we came back to it.

On 8 March 1983, the club – on the brink of financial ruin – had been set a deadline of 5pm by the Football League to obtain approval for a rescue package to be put before the High Court. With 25 minutes to go before they faced being wound up completely, the High Court gave its approval. Though the club had managed to hold off the ultimate disaster, their fortunes did not improve much in the years that followed and they played their last home match at The Valley on 21 September 1985, before a lengthy spell at Selhurst Park.

The Valley had effectively been left to rot for the rest of the 1980s, with all of its contents still in it. After the return to The Valley in 1992, the museum had salvaged minutes of board meetings and accounts of the financially ravaged club among other items available for its visitors’ perusal.

‘This is an amazing archive,’ I told them.

‘And this was all just here?’

They nodded, as they began to tell me about those bygone days.

Alan Dryland was born 33 days after Charlton’s much spoken of 1-0 victory against Burnley in the 1947 FA Cup final. He liked to think of himself as not only a lifelong fan, but an antenatal one, too.

He came to the club in the traditional way – his dad had been a fan and took him to his first match on 30 April 1955. It was the last game of the season, but Alan counted it as the whole of the 1954/55 season, because it gave him an extra year of fandom, he said – 67 seasons, in total. He still had the programme, which he would later show me as evidence of this. Charlton had lost 4-0 that day to Preston North End, but seven-year-old Alan fell instantly in love, nonetheless.

‘They say that you don’t choose your club, your club chooses you,’ he told me. ‘Once you’re hooked – you’re hooked.’

Back then, Alan lived with his family in Borough Green, mid-Kent, and was dependent on lifts to The Valley until he was considered old enough to make the journey by himself, at which point he began attending matches more regularly. As with many families and football, it was a tradition that Alan had in turn passed on to his two sons, and his grandson had been at the epic playoff final against Sunderland, that summer.

These days, he said, 90 per cent of his interest in coming to The Valley was social.

‘You still go,’ he told me, ‘because of course, what happens at three o’clock is irrelevant to all the talking rubbish and having the drink that you had before.’

‘And there’s the stadium – we’re very proud of it,’ he added. ‘Rightly so, it’s a good place to come. It’s not some soulless shed.’

He’d lived for 25 years in a flat overlooking The Valley, he told me, and he remembered well the first time he’d shown his sons, who’d been ecstatic by the proximity to the stadium.

In his 66 (or 67) years of supporting the club, he’d seen some things. This current turbulence with Roland was nothing new, really. Though a bit before his time, the tensions between Duchatelet and Bowyer, recently exposed through a series of bonkers press notices about the failure to agree terms of a new contract, were not unlike those between former manager and owners Jimmy Seed and the Gliksten family. Though fortunately for the Glikstens, they’d had neither Twitter nor the Voice of The Valley fanzine to contend with back in those days.

The conversation meandered wildly as the two fans held court, opining on everything from those tensions to the current prospects of the club. ‘It’s all built on sand,’ Nick sighed, lamenting the absence of any substantive signings over the summer transfer window – on to one of Alan’s favourite Charlton anecdotes.

‘I’ll tell the story which always makes my sons roll their eyes in disbelief,’ he began, describing how his then partner, while planning a holiday, had accidentally chosen a hotel that happened to be the England camp at the 2000 Euros, hosted by Belgium and Netherlands.

1966 England hero Geoff Hurst had been part of the FA’s coaching setup at the time, and during a chance encounter with him, Alan told him he’d been at Wembley in ’66, but his was the second best hat-trick he’d ever seen at Wembley.

‘“Second best, who was the best?”’ Alan repeated. ‘I said Clive Mendonca.’

‘Oh Charlton,’ had apparently been Hurst’s response, with a sigh.

In 2005 at Charlton’s centenary celebrations, Alan had the chance to recall this moment to Mendonca himself.

‘“What did he say? What did he say?”’ Alan mimicked Mendonca’s response in a North-East accent.

‘It was a brilliant moment,’ he chuckled, adding, ‘so Charlton gives you this. I mean, you might have to wait twenty years for the next one, but they’re worth it when they come.’

Eventually, we settled on the meaty subject of the club’s return to The Valley back in 1992, a moment I had been keen to learn more about. The club had a long history of protest, it seemed, and Alan was visibly excited as he told me all about it.

‘We formed a political party,’ he told me, referring to the fans’ attempts to return to The Valley in the early nineties.

By this point, Greenwich Council was not keen on the club returning to SE7, because of a feared impact on the local community. In 1988, the club’s first protest group of sorts was formed, by way of Rick Everitt’s Voice of The Valley – it was, as far as I could tell, the 1980s version of Arsenal Fan TV, and probably about as popular with Greenwich County Council as AFTV with Arsène Wenger.

In 1990, Greenwich Council rejected a planning application made by the club to rebuild its derelict grounds – but shit was about to get extremely real for them, as CAFC fans, much like their beleaguered players, would not take no for an answer. As Bowyer himself would say – and frequently did in post-match interviews – ‘They don’t know when they’re beaten.’

Fielding candidates in the local elections on 3 May 1990, The Valley Party polled almost 15,000 votes – an astonishing 10.9 per cent of the vote. It wasn’t enough to usurp the very safe Labour council who took 43.6 per cent of the vote share, but it was enough to split the vote of Councillor Simon Oelman, chair of planning, and for the local politicians to start taking Charlton’s fans seriously. But not before a punch-up between Oelman and The Valley Party’s photographer that evening, outside the town hall.

As they continued with their story, Alan and Nick chuckled to themselves retelling this moment of glory.

‘We were going to stand for election in Belgium,’ Alan told me. I was not sure they’d actually have been allowed, not being Belgian and all that, but I appreciated the gesture.

‘So they just settled for graffitiing Roland’s yard instead?’ I asked.

‘I don’t think that was our fans,’ Alan told me. ‘The language was all wrong.’

‘If you’re researching, you’ll need this,’ he said, handing me a copy of a book called Back to The Valley, by Everitt, now himself the Labour Party leader of Thanet District Council.

‘Do you take cards in here?’ I asked, explaining ‘I don’t have any cash on me,’ as they chortled at the prospect of such technological facilities.

‘No, no, have that,’ Alan said, handing me another book, Charlton Athletic: A Nostalgic Look at a Century of the Club, apparently part of the curiously named When Football Was Football series.

‘This is embarrassing,’ I said.

‘No, no,’ Alan said again. ‘If you’re going to spread the word, we’d like you to have them.’

A little lump rose in the back of my throat, because this was what it meant to be a Charlton fan. This you could not expect to find on a tour of the Emirates.

‘I’ll come back,’ I said, promising a future donation, as Nick became distracted by another visitor in the museum.

‘He’s in here all the time,’ he said, gesturing at a man in a tracksuit and baseball cap, loitering by some shirts. He had missed an unfeasibly small number of home games in the last few years, they told me.

‘I’d like to talk to you some more about your project,’ Alan told me. ‘I live in Woolwich and I’ve been in this area for a long time.’

And so I wrote my email address down for him and bid him good day, about to head off in search of artisanal bread in the Village. They both looked a little uncomfortable as I gushed earnest – and really very sincere – gratitude for their time and the books.

•

Less than 24 hours since my trip to the museum, and several discussions with disinterested parties about how Charlton was even more interesting than I had imagined, I received an email from Alan.

‘Jennifer,’ he wrote. ‘It was a great pleasure to meet you in the Museum yesterday. I’m sorry if I hijacked your visit, but meeting a delightful lady Addick in such heady surroundings easily starts me off!!’

He informed me he could be found in the fans’ bar ahead of most home matches, and asked me to keep in touch, thus starting an exchange that would continue for much of the rest of the season.

THE SEASON BEGINS

August: Charlton Athletic v Stoke City

Contrary to all expectations, we began the 19/20 season with victory – 2-1 away to Blackburn. I was feeling tentatively hopeful.

‘Dude, 3pts!’ I texted Michael.

‘I know! Totally wasn’t expecting that!’ he replied.

The following week was our opening home fixture, against Stoke City, and a first outing for the Offord family season tickets.

Having to go to the Edinburgh Fringe for work, I had to miss this one, so Kerry went in my place. It followed the end of a particularly stressful week leading up to deadline day in the transfer window, the first I had cared about for – well, ever, I suppose.

Working in sports journalism it was impossible to care beyond finding Sky Sports News’ apocalyptic coverage of it amusing, along with the occasional ‘Lionel Messi spotted in Bognor Regis!’ type tweet. Or that time Moussa Sissoko ghosted Ronald Koeman on deadline day. Which was genuinely funny.