6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A searing and luminous novel of a family's grief after unexpected loss, from the author of the huge bestseller Wild. "Work hard. Do good. Be incredible!" is the advice Teresa Rae Wood shares with the listeners of her local radio show, Modern Pioneers, and the advice she strives to live by every day. She has fled a bad marriage and rebuilt a life with her children, Claire and Joshua, and their caring stepfather, Bruce. Their love for each other binds them as a family through the daily struggles of making ends meet. But when they received unexpected news that Teresa, only 38, is dying of cancer, their lives all begin to unravel and drift apart. Strayed's intimate portraits of these fully human characters in a time of crisis show the varying truths of grief, forgiveness, and the beautiful terrors of learning how to keep living.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Torch

by Cheryl Strayed

© Joni Kabana

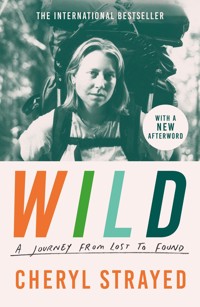

Cheryl Strayed is the author of the critically acclaimed novel Torch, the huge New York Times-bestselling memoir Wild and the collection of essays Tiny Beautiful Things: Advice on Love and Life from Someone Who’s Been There. Her work has appeared in numerous magazines and journals, including The New York Times Magazine, The Washington Post Magazine, Allure and The Rumpus. She lives in Portland, Oregon.

BOOKS BY CHERYL STRAYED

Torch

Tiny Beautiful Things: Advice on Love and Life from Someone Who’s Been There

Wild: From Lost to Found

First published in the United States in 2005 by Houghton Mifflin, Inc., New York.

This edition published in the United States in 2012 by Vintage Books, a division of the Penguin Random House Company.

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Cheryl Strayed, 2005, 2012

The moral right of Cheryl Strayed to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Grove/Atlantic, Inc.: Excerpt from “Late Fragment” from A New Path to the Waterfall by Raymond Carver. Copyright © 1989 by the Estate of Raymond Carver. Used by permission of Grove/Atlantic, Inc. Any third party use of this material, outside of this publication, is prohibited.

Random House and Curtis Brown, Ltd.: Excerpt from “September 1, 1939”, from Collected Poems of W. H. Auden by W. H. Auden. Copyright © 1940 and renewed 1968 by W. H. Auden. Used by permission of Random House, Inc. on behalf of print rights and Curtis Brown, Ltd. On behalf of electronic rights. Any third party use of this material, outside of this publication, is prohibited. Interested parties must apply directly to Random House, Inc. for permission.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 537 9 E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 538 6

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Brian Jay Lindstrom

and

In memory of my mother, Bobbi Anne Lambrecht,

with love

Contents

Preface

Part I The Woods of Coltrap County

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Part II Good

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part III Mud Days

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Part IV Company

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part V Torch

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Acknowledgments

PREFACE

When I was nine someone gave me a blank diary. I don’t remember who. It was pure white and had a small golden lock that opened with a small golden key that was also meant to re-secure the lock, but never did. I loved that diary. I remember very distinctly knowing it was the best gift I’d ever received. I filled it with stories about princesses and kings, about horses ridden by girls whose fathers drove around in fancy cars. I wrote about things that were nothing about me.

When I was eleven a poet came to my school to teach a class for several days. She was called a poet-in-the-school, a special guest, a rare occurrence. Every minute she spoke it was like someone was holding a lit match to the most flammable, secret parts of me. One day the poet-in-the-school explained what metaphors were and then asked us to write a whole poem composed of them. I was a lion. I was an icicle. I was a kaleidoscope. I was a torn-up page. I was glass that other people took to be stone. Another day she told us we could write poems about our memories. She asked us to close our eyes and think for a while about when we were younger and then open our eyes and write. I wrote about running down the sidewalk in what I called “beautiful, filthy Pittsburgh” in my paint-speckled sneakers when I was five.

A week later the principal summoned me to his office. When I arrived he explained from behind his big desk that the poet-in-the-school had showed him my poem. “You’re a good writer!” he exclaimed. His name was Mr. Menzel. He was the first person to ever say this to me. He handed me a copy of my poem and asked if I would read it out loud to him and I did, mortified but also happy. After I was done reading he said it was surprising that I’d described Pittsburgh as being beautiful and filthy because most people would think it could not be both things at once. “Keep writing, Cheryl,” he said.

I kept writing.

I didn’t know that by doing so I was becoming a writer. I knew people wrote books, but it didn’t occur to me that I could be one of them until I was twenty and a junior at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, enrolled in an introductory poetry class taught by Michael Dennis Browne. I learned a lot in that class. I came to understand language in a way I’d never understood it. I wrote my first serious (though lousy) poems. But most important, I got to be in a room a few times a week with a writer who’d written not just one book, but many, and it was only then that it dawned on me that even though the gap between who he was and who I was seemed enormous, maybe—just maybe—I could bridge that gap and someday be a person who wrote a book too.

I’ve often been asked how long it took me to write Torch. There are three answers to this question and they are all true: four years, seven years, and thirty-four years. But the last answer is the truest. Torch is born of the little white diary with the lock that wouldn’t work, the poet-in-the-school who taught me what a metaphor was, the principal who said keep writing, the writer whose existence showed me the way. They are not in the acknowledgments of this book, but they are in its blood. Torch is the story I had broiling in my bones for the first thirty-four years of my life. It’s the story I felt I could not live without telling. The one that made me think I could die when I finished writing it (though I can’t and don’t want to). Perhaps every writer has this relationship to his or her first book. I worked my tail off when I wrote my other books, Wild and Tiny Beautiful Things, but Torch is the book that taught me how to write a book and because of that it was the one that demanded the deepest faith, the greatest leap, the furthest reach.

Torch is a novel about a family in rural northern Minnesota during a time of great loss. Because I grew up in a place not unlike the place depicted in the novel and because my family experienced a great loss not unlike that of the Wood/Gunther family in the book, many people read Torch as if it’s nonfiction, but it is not. Like a lot of novelists, I drew on my life experiences while writing Torch—those who’ve read my other books will undoubtedly recognize some details about my mother and her death and the general landscape and culture of rural Aitkin County, Minnesota, where I came of age—but the autobiographical elements were only the seeds from which I created a fictional world.

Though it’s true my family and I listened to radio shows of the sort Teresa Wood hosts in Torch on the very real community station KAXE, my mother wasn’t a radio show host and I can’t imagine she’d have wanted to be, given the opportunity. My brother didn’t go to jail for dealing methamphetamines like Joshua Wood does. My stepfather wasn’t an only child who obsessively listened to the music of Kenny G in his grief like Bruce Gunther does. I didn’t have an affair while my mother lay dying in a hospital in Duluth like Claire Wood does.

In writing Torch, I wanted to tell a story that had no obligation to what actually happened and yet what happened had everything to do with my need to write Torch. One of the great paradoxes of writing fiction is that it’s often only through imagination that a writer can reveal the greatest truth. I certainly felt that way as I wrote Torch. I don’t know precisely what it meant for my stepfather to lose his wife or for my siblings to lose their mother, but in Torch I tried very hard to know. Fiction gave me license to seek. It allowed me to tell the only story I could at the time, one that exceeded the bounds of my own particular grief—a grief that was so enormous I couldn’t hold it alone. I needed to cast it into other bodies, other minds, and also to pay those other people their due. They had lost my mother too. I put the story of my family’s sorrow on a larger, mostly make-believe stage so I could make sense of how any of us had managed to come out the other side. In doing so, my allegiance wasn’t accuracy. It was emotional truth.

That’s what I mean when I tell you that Torch was broiling in my bones. It was the story of my life and yet I made everything up. I created characters, even as I felt the people I knew and loved in every word I wrote. I set the story in a place that both was and was not home. I named the town in Torch Midden—the medieval word for a communal garbage heap—not because I wanted to imply my beloved hometown of McGregor was a dump, but because a midden is the most valuable find when archeologists do their excavations. It’s the place where we recover the hidden treasures, both grand and mundane. In middens, the story of a people and a place can be found, but only if we dig.

Torch is the result of my first sustained effort at digging. When I scratched beneath the surface as I wrote it, I came to understand I didn’t know what I was going to find as each layer revealed itself. It was only after I’d finished that I could see what I’d done: written a novel not only about grief and loss, but also about love in its many forms, about how we find light in the midst of the most profound darkness, about how we survive what we think we will not. And it’s only from this vantage point—years after Torch was first published—that I can see all of my books are about that. How things can be both beautiful and filthy at once.

PART I

The Woods of Coltrap County

Yet it would be your duty to bear it, if you could not avoid it: it is weak and silly to say you cannot bear what it is your fate to be required to bear.

—CHARLOTTE BRONTË, Jane Eyre

1

She ached. As if her spine were a zipper and someone had come up behind her and unzipped it and pushed his hands into her organs and squeezed, as if they were butter or dough, or grapes to be smashed for wine. At other times it was something sharp like diamonds or shards of glass engraving her bones. Teresa explained these sensations to the doctor—the zipper, the grapes, the diamonds, and the glass—while he sat on his little stool with wheels and wrote in a notebook. He continued to write after she’d stopped speaking, his head cocked and still like a dog listening to a sound that was distinct, but far off. It was late afternoon, the end of a long day of tests, and he was the final doctor, the real doctor, the one who would tell her at last what was wrong.

Teresa held her earrings in the palm of one hand—dried violets pressed between tiny panes of glass—and put them on, still getting dressed after hours of going from one room to the next in a hospital gown. She examined her shirt for lint and cat hair, errant pieces of thread, and primly picked them off. She looked at Bruce, who looked out the window at a ship in the harbor, which cut elegantly, tranquilly along the surface of the lake, as if it weren’t January, as if it weren’t Minnesota, as if it weren’t ice.

At the moment she wasn’t in pain and she told the doctor this while he wrote. “There are long stretches of time that I feel perfectly fine,” she said, and laughed the way she did with strangers. She confessed that she wouldn’t be surprised if she were going mad or perhaps this was the beginning of meno-pause or maybe she had walking pneumonia. Walking pneumonia had been her latest theory, the one she liked best. The one that explained the cough, the ache. The one that could have made her spine into a zipper.

“I’d like to have one more glance,” the doctor said, looking up at her as if he had risen from a trance. He was young. Younger. Was he thirty? she wondered. He instructed her to take her clothes off again and gave her a fresh gown to wear and then left the room.

She undressed slowly, tentatively at first, and then quickly, crouching, as if Bruce had never seen her naked. The sun shone into the room and made everything lilac.

“The light—it’s so pretty,” she said, and stepped up to sit on the examining table. A rosy slice of her abdomen peeped out from a gap in the gown, and she mended it shut with her hands. She was thirsty but not allowed a drop of water. Hungry, from having not eaten since the night before. “I’m starving.”

“That’s good,” said Bruce. “Appetite means that you’re healthy.” His face was red and dry and cracked-looking, as if he’d just come in from plowing the driveway, though he’d been with her all day, going from one section of the hospital to the next, reading what he could find in the waiting rooms. Reading Reader’s Digest and Newsweek and Self against his will but reading hungrily, avidly, from cover to cover. Throughout the day, in the small spaces of time in which she too had had to wait, he’d told her the stories. About an old woman who’d been bludgeoned to death by a boy she’d hired to build a doghouse. About a movie star who’d been forced by divorce to sell his boat. About a man in Kentucky who’d run a marathon in spite of the fact that he had only one foot, the other made of metal, a complicated, sturdy coil fitted into a shoe.

The doctor knocked, then burst in without waiting for an answer. He washed his hands and brought his little black instrument out, the one with the tiny light, and peered into her eyes, her ears, her mouth. She could smell the cinnamon gum he chewed and also the soap he’d used before he touched her. She kept herself from blinking while staring directly into the bullet of light, and then, when he asked, followed his pen expertly around the room using only her eyes.

“I’m not a sickly woman,” she declared.

Nobody agreed. Nobody disagreed. But Bruce came to stand behind her and rub her back.

His hands made a scraping sound against the fabric of the gown, so rough and thick they were, like tree bark. At night he cut the calluses off with a jackknife.

The doctor didn’t say cancer—at least she didn’t hear him say it. She heard him say oranges and peas and radishes and ovaries and lungs and liver. He said tumors were growing like wildfire along her spine.

“What about my brain?” she asked, dry-eyed.

He told her he’d opted not to check her brain because her ovaries and lungs and liver made her brain irrelevant. “Your breasts are fine,” he said, leaning against the sink.

She blushed to hear that. Your breasts are fine.

“Thank you,” she said, and leant forward a bit in her chair. Once, she’d walked six miles through the streets of Duluth in honor of women whose breasts weren’t fine and in return she’d received a pink T-shirt and a spaghetti dinner.

“What does this mean exactly?” Her voice was reasonable beyond reason. She became acutely aware of each muscle in her face. Some were paralyzed, others twitched. She pressed her cold hands against her cheeks.

“I don’t want to alarm you,” the doctor said, and then, very calmly, he stated that she could not expect to be alive in one year. He talked for a long time in simple terms, but she could not make out what he was saying. When she’d first met Bruce, she’d asked him to explain to her how, precisely, the engine of a car worked. She did this because she loved him and she wanted to demonstrate her love by taking an interest in his knowledge. He’d sketched the parts of an engine on a napkin and told her what fit together and what parts made other parts move and he also took several detours to explain what was likely to be happening when certain things went wrong and the whole while she had smiled and held her face in an expression of simulated intelligence and understanding, though by the end she’d learned absolutely nothing. This was like that.

She didn’t look at Bruce, couldn’t bring herself to. She heard a hiccup of a cry from his direction and then a long horrible cough.

“Thank you,” she said when the doctor was done talking. “I mean, for doing everything you can do.” And then she added weakly, “But. There’s one thing—are you sure? Because . . . actually . . . I don’t feel that sick.” She felt she’d know it if she had oranges growing in her; she’d known immediately both times that she’d been pregnant.

“That will come. I would expect extremely soon,” said the doctor. He had a dimpled chin, a baby face. “This is a rare situation—to find it so late in the game. Actually, the fact that we found it so late speaks to your overall good health. Other than this, you’re in excellent shape.”

He hoisted himself up to sit on the counter, his legs dangling and swinging.

“Thank you,” she said again, reaching for her coat.

Carefully, wordlessly, they walked to the elevator, pushed its translucent button, and waited for it to arrive. When it did, they staggered onto it and saw, gratefully, that they were alone together at last.

“Teresa,” Bruce said, looking into her eyes. He smelled like the small things he’d eaten throughout the day, things she’d packed for him in her famously big straw bag. Tangerines and raisins.

She put the tips of her fingers very delicately on his face and then he grabbed her hard and held her against him. He touched her spine, one vertebra, and then another one, as if he were counting them, keeping track. She laced one hand into his belt loop at the back of his jeans and with the other hand she held a seashell that hung on a leather string around her neck. A gift from her kids. It changed color depending on how she moved, flashing and luminescent like a tropical fish in an aquarium, so thin she could crush it in an instant. She considered crushing it. Once, in a quiet rage, she’d squeezed an entire bottle of coconut-scented lotion onto the tops of her thighs, having been denied something as a teenager: a party, a record, a pair of boots. She thought of that now. She thought, Of all the things to think of now. She tried to think of nothing, but then she thought of cancer. Cancer, she said to herself. Cancer, cancer, cancer. The word chugged inside of her like a train starting to roll. And then she closed her eyes and it became something else, swerving away, a bead of mercury or a girl on roller skates.

They went to a Chinese restaurant. They could still eat. They read the astrology on the placemats and ordered green beans in garlic sauce and cold sesame noodles and then read the placemats again, out loud to each other. They were horses, both of them, thirty-eight years old. They were in perpetual motion, moved with electric fluidity, possessed unconquered spirits. They were impulsive and stubborn and lacked discretion. They were a perfect match.

Goldfish swam in a pond near their table. Ancient goldfish. Unsettlingly large goldfish. “Hello, goldfish,” she cooed, tilting toward them in her chair. They swam to the surface, opening their big mouths in perfect circles, making small popping noises.

“Are you hungry?” she asked them. “They’re hungry,” she said to Bruce, then looked searchingly around the restaurant, as if to see where they kept the goldfish food.

At a table nearby there was a birthday party, and Bruce and Teresa were compelled to join in for the birthday song. The woman whose birthday it was received a flaming custard, praised it loudly, then ate it with reserve.

Bruce held her hand across the table. “Now that I’m dying we’re dating again,” she said for a joke, though they didn’t laugh. Sorrow surged erotically through them as if they were breaking up. Her groin was a fist, then a swamp. “I want to make love with you,” she said, and he blinked his blue eyes, tearing up so much that he had to take his glasses off. They’d tapered off over the years. Once or twice a month, perhaps.

Their food arrived, great bowls of it, and they ate as if nothing were different. They were so hungry they couldn’t speak, so they listened to the conversation of the happy people at the birthday party table. The flaming custard lady insisted that she was a dragon, not a rabbit, despite what the placemat said. After a while they all rose and put their heavy coats on, strolling past Teresa and Bruce, admiring the goldfish in their pond.

“I had a goldfish once,” said a man who held the arm of the custard lady. “His name was Charlie.” And everyone laughed uproariously.

Later, after Bruce paid the bill, they crossed a footbridge over a pond where you could throw a penny.

They threw pennies.

On the drive home it hit them, and they wept. Driving was good because they didn’t have to look at each other. They said the word, but as if it were two words. Can. Sir. They had to say it slowly, dissected, or not at all. They vowed they would not tell the kids. How could they tell the kids?

“How could we not?” Teresa asked bitterly, after a while. She thought of how, when the kids were babies, she would take their entire hands into her mouth and pretend that she was going to eat them until they laughed. She remembered this precisely, viscerally, the way their fingers felt pressing onto her tongue, and she fell forward, over her knees, her head wedged under the dash, to sob.

Bruce slowed and then pulled over and stopped the truck. They were out of Duluth now, off the freeway, on the road home. He hunched over her back, hugging her with his weight wherever he could.

She took several deep breaths to calm herself, wiped her face with her gloves, and looked up out the windshield at the snow packed hard on the shoulder of the road. She felt that home was impossibly far.

“Let’s go,” she said.

They drove in silence under the ice-clear black sky, passing turkey farms and dairy farms every few miles, or houses with lit-up sheds. When they crossed into Coltrap County, Bruce turned the radio on, and they heard Teresa’s own voice and it shocked them, although it was a Thursday night. She was interviewing a dowser from Blue River, a woman named Patty Peterson, the descendant of a long line of Petersons who’d witched wells.

Teresa heard herself say, “I’ve always wondered about the art—I suppose you could call it an art—or perhaps the skill of selecting a willow branch.” And then she switched the radio off immediately. She held her hands in a clenched knot on her lap. It was ten degrees below zero outside. The truck made a roaring sound, in need of a new muffler.

“Maybe it will go away as mysteriously as it came,” she said, turning to Bruce. His haggard face was beautiful to her in the soft light of the dashboard.

“That’s what we’re going to shoot for,” he said, reaching for her knee. She considered sliding over to sit close to him, straddling the clutch, but felt tied to her place near the dark window.

“Or I could die,” she said calmly, as if she’d come to peace with everything already. “I could very well die.”

“No, you couldn’t.”

“Bruce.”

“We’re all going to die,” he said softly. “Everyone’s going to die, but you’re not going to die now.”

She pressed her bare hand flat onto the window, making an imprint in the frost. “I didn’t think I’d die this way.”

“You have to stay positive, Ter. Let’s get the radiation started and then we’ll see. Just like the doctor said.”

“He said we’ll see about chemo. Whether I’ll be strong enough for chemo after I’m done with radiation, not about me being cured, Bruce. You never pay attention.” She felt irritated with him for the first time that day and her irritation was a relief, as if warm water were being gently poured over her feet.

“Okay, then,” he said.

“Okay what?”

“Okay, we’ll see. Right?”

She stared out the window.

“Right?” he asked again, but she didn’t answer.

They drove past a farm where several cows stood in the bright light of the open barn, their heads turned toward the dark of the woods beyond, as if they detected something there that no human could. A thrashing.

2

The sound of his mother’s voice filled Joshua with shame.

“This is Modern Pioneers!” she exclaimed from all four of the speakers in the dining room of the Midden Café and the one speaker back in the kitchen that was splattered with grease and soot and ketchup. Joshua listened to the one in the kitchen as he scrubbed pots with a ball of steel wool, his arms elbow-deep in scorching, soapy water. Hearing his mother’s voice made his head hurt, as if a dull yet pointed object were being pressed into his eardrums. Her radio voice was exactly like she was: insistent, resolute, amused, wanting to know. Wanting to know everything from everyone she interviewed. “So, how exactly, can you tell us, do you collect the honey from the bees?” she’d ask, dusky and smooth. Other times she held forth for the entire hour herself, discussing organic gardening and how to build your own cider press, quilting and the medicinal benefits of ginseng. Once, she’d played “Turkey in the Straw” on her dulcimer for all of northern Minnesota to hear and then read from a book about American folk music. Recently, she had announced how much money she’d spent on tampons in six months and then proceeded to describe other, less costly options: natural sponges and cotton pads that she’d sewn herself out of Joshua and Claire’s old shirts. She’d actually said that: Joshua and Claire’s old shirts. Claire was off to college by then, leaving Joshua alone to wallow in humiliation the first week of his senior year of high school.

Marcy pushed her way back into the kitchen through the swinging door, holding a stack of dirty plates with uneaten edges of food and wadded-up napkins. She set them on the counter where Joshua had just finished cleaning up and then reached into her apron for a cigarette. Joshua watched her, trying to appear not to, as he scraped off the dishes. She was in her late twenties, married, with two kids, short and big-breasted, which made her look heavier than she was. Joshua spent a lot of his time at work trying to decide whether he thought she was pretty or not. He was seventeen, lanky and fair, quiet but not shy.

His mother was talking to a dowser named Patty Peterson. He could hear Teresa’s animated voice and then Patty’s quavering one. Marcy stood listening, untied her apron, and tied it again more tightly. “Next thing you know your mom will go down to Africa and teach us all about it. Maybe the way they go to the bathroom down there.”

“She would like to go to Africa,” Joshua said, dumb and steadfast and serious, refusing to acknowledge even the slightest joke about his mother. She would go to Africa, he knew. She’d go anywhere, she’d leap at the chance.

“They got an African over in Blue River now. Some adopted kid,” Vern said from the back door. He had it propped open with a bucket despite the cold. Marcy was the owner’s daughter; Vern, the night cook.

“Not African, Vern. Black,” said Marcy. “He’s from the Cities. That’s not Africa.” She adjusted the barrette that held her curly hair up at the back of her head. “Are you trying to freeze us all to death in here?”

Vern shut the door. “Maybe your mom will interview the African,” he said. “Tell us what he has to say for himself.”

“Be nice,” Marcy said. She went up on her tiptoes and pulled a stack of Styrofoam containers down from the top shelf, clenching her cigarette in her mouth. “Nothing against your mom, Josh,” she said. “She’s a super nice lady. An interesting lady. It takes all kinds.” With great care, she tapped the burning end of her cigarette on a plate, then she blew on it and put it back into her apron pocket and buzzed out the door.

Six years ago, when his mother had first started the show, Joshua hadn’t felt ashamed. He’d been proud, as if he had been hoisted up onto a platform and was glowing red-hot and lit up from within. He believed his mother was famous, that they all were—he and Claire and Bruce. Teresa had made them part of the show; his life, their lives, were the fodder. She made them eat raw garlic to protect against colds and heart disease, rub pennyroyal on their skin to keep the mosquitoes away, drink a tea of boiled jack-in-the-pulpit when they had a cough. They could not eat meat, or when they did they had to kill it themselves, which they did one winter when they’d butchered five roosters that as chicks they’d thought were hens. They shook jars of fresh cream until it congealed into lumps of butter. His mother got wool straight off a neighbor’s sheep and carded it and spun it on a spinning wheel that Bruce had built for her. She saved broccoli leaves and collected dandelions and the inner layers of bark from certain trees and used these things to make dye for the yarn. It came out the most unlikely colors: red and purple and yellow, when you might have expected mudlike brown or green. And then their mother would tell everyone all about what the family did on the radio. Their successes and failures, discoveries and surprises. “We are all modern pioneers!” she’d say. Listeners would call in to ask her questions on the air, or would call her at home for advice. Slowly at first, and then overnight it seemed, Joshua didn’t want to be a modern pioneer anymore. He wanted to be precisely what everyone else was and nothing more. Claire had stopped wanting to be a modern pioneer well before that. She insisted on wearing makeup and got into raging fights with their mother and Bruce about why they could not have a TV, why they could not be normal. These were the same fights Joshua was having with them now.

“You’re going to have to clean the fryer too,” said Vern. “Don’t go trying to leave it for Angie.”

Joshua went back to scrubbing, turning the hot water on full blast. The steam felt good on his face, opening the pores. Pimples bloomed on the rosy part of his cheeks and the wide plain of his forehead. At night in bed he scratched them until they bled, and then he would get up and put hydrogen peroxide on them. He liked the feeling of the bubbles, eating everything away.

“You hear what I told you?” Vern said, when Joshua shut the water off.

“Yep.”

“What?”

“I said I did,” he said more harshly, turning his blue eyes to Vern: a gaunt old man with a paunch and a bulbous red nose. One arm had a tattoo of a hula dancer, the other a hooked anchor with a rope wound around it.

“Well, answer me, then. Show some respect for your elders.” Vern stood near the door in his apron and T-shirt, which were caked with smudges the color of barbeque sauce where he had wiped his hands. He opened the door again and tossed his cigarette butt into the darkness. Outside there was a concrete landing, glazed with ice, and an alley where Joshua’s truck and Vern’s van were parked along the back wall of Ed’s Feed.

Joshua lifted the sliding hood of the dishwasher, and the steam roiled out. He slid a clean rack of flatware out and began to sort the utensils into round white holders as he wiped each one quickly with a towel.

“Running behind tonight, ain’t you?”

“Nope.” On the radio he heard his mother laugh, and the well-witcher laughed too, and then they settled back into their discussion, serious as owls.

“Ain’t you?”

“I said no.”

“Maybe you’re gonna have to learn that when a man’s got a job, a man’s gotta show up on time, ain’t you?”

“Yep.”

“I seen you left the lasagna pan for Angie last night. Don’t go thinking that I don’t see. ’Cause I see. I see everything your shit for brains can think up about two weeks before you get to it. And I knowed you’re always thinking things. Trying to see what you can get away with. Ain’t you?”

“Nope.”

Vern watched Joshua, slightly bent from the waist, a cigarette smoking between his lips, as though he were trying to come up with something else to say, running down the list of things that pissed him off. Joshua had known Vern most of his life, without having known him at all. It wasn’t until they worked together at the café that he even knew that Vern’s name was Vern—Vern Milkkinen. Before that, he’d known him as the Chicken Man, the way most people in Midden did, because he spent his summers in the Dairy Queen parking lot selling baby chicks and eggs and an ever-changing assortment of homemade canned goods, soap, beeswax candles, and his special chokecherry jam. It had never occurred to Joshua to wonder what the Chicken Man—what Vern—did to occupy his time in the months that he wasn’t selling things until he walked into the kitchen at the café and saw Vern standing there, butcher knife in hand.

On that first day working together, Vern did not indicate that he remembered Joshua, seemingly unconscious of the fact that he’d actually watched him grow up, from four to seventeen, laying eyes on him during those fourteen summers at least once a week, first as a child, when Joshua would go with his mother to purchase things from the Chicken Man, and then later when he was sent on his own. The DQ parking lot was the closest thing Midden had to a town square because it also shared its parking lot with the Kwik Mart and Gas, and Bonnie’s Burger Chalet. Every week he and the Chicken Man would exchange a nod or the slightest lift of the chin or hand. Once, when Joshua was ten, the Chicken Man asked him if he liked girls, if he had a girlfriend yet, if he’d ever kissed a girl, if he’d preferred brunettes or blonds.

“Or redheads. Them are the ones to watch out for. Them are the ones with the tightest pussies,” Vern had said, and then roared with laughter.

Vern had shown Joshua his anchor tattoo and asked him if he’d ever heard of the cartoon Popeye the Sailor Man.

“Yes,” Joshua said solemnly, holding out the money his mother had given him.

“That’s me. That’s who I am,” Vern said, his eyes wild and mystical, as if he’d been transported into a memory of a time when he’d been secretly heroic. “Only I’m the original one, not a cartoon.” And then he laughed monstrously again while Joshua faked a smile.

It had taken Joshua several years to fully shake the sense that Vern was Popeye, despite the fact that Vern’s real life was on obvious display. He had a son named Andrew, who was older than Joshua by twenty years. At work, when Vern was in a good mood, he would tell Joshua stories about Andrew when he was young. Andrew shooting his first deer, Andrew and his legendary basketball abilities, Andrew getting his arm broken by Vern when he’d caught him smoking pot in eighth grade. “I just took the little bugger and twisted it till it snapped,” Vern said. “I woulda pulled it clean off if I could. That’s how he learned. I don’t mess around. Messing around’s not how you raise a kid. You mess around and then they never get toughened up.”

Joshua hardly knew his own father. He lived in Texas now. Joshua and Claire had gone to visit him there once when Joshua was ten, but they hadn’t lived with him since Joshua was four. They didn’t live in Midden then. They lived in Pennsylvania, where their father was a coal miner. They moved to Midden without ever having known about its existence until shortly before they’d arrived on a series of Greyhound buses, their mother having secured a job in housekeeping at the Rest-A-While Villa through the cousin of a friend.

Marcy came back into the kitchen and sat on an upturned bucket that they used as a chair. “I’ll have the pork tenderloin tonight, Vern. With a baked potato. You can keep the peas. You got a baked potato for me?”

Vern nodded and closed the door he’d opened again.

“Is it thinking about snowing out there?” she asked, looking at her nails.

“Too cold to snow,” he said.

All three of them listened to Teresa ask Patty Peterson what she thought the future of dowsing held and Patty told her it was a dying art. The radio show wasn’t Teresa’s real job; she was a volunteer, like almost everyone who worked at the station. Her real job was waiting tables at Len’s Lookout out on Highway 32. She’d started there after the Rest-A-While Villa closed down ten years before.

Marcy grabbed the baseball cap off of Joshua’s head and then put it back on crooked. “Tell Vern what you want for dinner so we can get the hell out of Dodge when it’s time. I’m gonna go sweep.”

“Onion rings, please,” he said, and loaded up another tray of dirty dishes. On the radio, his mother asked what year the showy lady’s slipper was made the Minnesota state flower.

“1892,” said Vern. He opened the oven drawer and took out a potato wrapped in foil with his bare hands and dropped it onto a plate.

At the end of each show, his mother would ask a question and then would tell the listeners what next week’s show would be while she waited for them to call in and guess the answer. She practiced these questions on Joshua and Claire and Bruce. She had them name all seven of the dwarfs, or define pulchritudinous, or tell her which is the most populous city in India. The people who called in to the show were triumphant if they got the answer right, as if they’d won something, though there was no prize at all. What they got was Teresa asking where they were calling from, and she’d repeat the place name back to them, delighted and surprised. The names of cold, country places with Indian names or the names of animals or rivers or lakes: Keewatin, Atumba, Beaver, Deer Lake.

“1910?” a voice on the radio asked uncertainly.

“Nooo,” Teresa cooed. “Good guess, though.”

Vern stepped in front of Joshua holding the fryer basket with a pair of tongs and flung it into the empty sink. “That’s gonna be hot.”

“1892,” a voice said, and Teresa let out a happy cry.

Vern switched the radio off and Joshua felt a flash of gratitude. They wouldn’t have to hear where this week’s correct caller was from, wouldn’t have to hear Teresa say what she said each week at the end of her show. “And this, folks, brings us to the end of another hour. Work hard. Do good. Be incredible. And come back next week for more of Modern Pioneers!”

“Your bud’s out there,” Marcy said to Joshua when she came back into the kitchen. She put her coat on. “I locked the front so whoever leaves last go out the back.”

“It’ll be this guy,” Vern said, pulling his apron off. “ ’Cause it sure as shit ain’t gonna be me.”

• • •

Joshua changed out of his wet clothes in the kitchen when Vern left and took his plate of onion rings out front, where R.J. was playing Ms. Pac Man.

“I learned how to work it so we can play for free,” he said, once all of R.J.’s players had died.

“I don’t wanna play no more. Can I have some pop?”

Joshua poured them each a Mountain Dew from the dispenser. The café was peaceful without the overhead lights on, without any people in it but him and R.J. All the chairs sat upside down on the tables. R.J. wore jeans and a big sports jersey that wasn’t tucked in, his body a barrel. His dad was Ojibwe, his mom white. Like all the Ojibwes who lived in Midden, each fall he received free Reebok shoes from the Reebok company, which meant the guys at school sometimes dragged him into the boy’s bathroom, shoved his head into the toilet, and flushed it. Despite this, he and Joshua had been best friends since fifth grade.

“I got something if you ever wanna stay up all night.” R.J. pulled a glassine envelope, the kind that stamps come in, from his pocket. “Bender gave it to me.” Bender was his mom’s boyfriend.

“What is it?”

R.J. gently opened the envelope and shook the contents into his chubby palm. Gray crystals the size of salt fell out. “Crystal meth. Bender made it,” R.J. said, and blushed. “Don’t tell anyone. Bender and my mom did. Just to see.” His eyes were dark and bulbous. He resembled his father, a man whom R.J. seldom saw.

“Let’s try it,” Joshua said. He smoked pot often but hadn’t done anything else. R.J.’s mom and Bender kept all of Midden supplied with marijuana, growing it in a sub-basement under their front porch that only R.J. and Joshua and Bender and R.J.’s mom knew existed.

“Right now?” R.J. poked the meth with one finger.

“What’s it do?”

“Wakes you up and makes you hyper.”

Joshua licked his finger and dabbed it into the crystals and then put it in his mouth.

“What are you doing?”

“Rubbing it on my gums. That’s what you’re supposed to do is wipe it on your gums so it gets into your system,” Joshua said. He didn’t know this for a fact, but he vaguely remembered hearing something like this, or seeing it in a movie.

“You’re supposed to snort it,” R.J. said. “Bender told me.”

Joshua ignored him and sat down at a booth and closed his eyes, as if he were meditating.

“Are you a total fucking head case?” R.J. asked.

“You’re the head case,” Joshua said, keeping his eyes closed. “I’m letting it get into my system, you dumb fuck.”

“What’s it taste like?”

“Like medicine.”

“What’s it feel like?”

Joshua didn’t answer. He felt a small swooping sensation but couldn’t tell if it was a real feeling or if his desire to feel it had brought it on. He opened his eyes and the sensation went away. He said, “Let’s go drive around.”

R.J. carefully scraped most of the crystals back into the envelope, and then licked the rest of the meth from his palm.

Joshua drove. They drove through town without passing another moving vehicle. Ten p.m. was like the middle of the night. They drove past the dark storefronts—Ina’s Drug, the Red Owl grocery, Video and Tan, past the Universe Roller Rink and the Dairy Queen and the school and the Midden Clinic that sat in the school parking lot, a converted mobile home, double wide—and past the two places that were open, the Kwik Mart and Punk’s Hideaway, where Joshua knew that Vern would be—he went there every night. On the way out of town they went slowly by the Treetops Motel, where they could see Anita sitting on a flowered couch in the front office, which was also her living room, watching the news. They drove out Highway 32, past Len’s Lookout, where Joshua’s mother worked, and continued east for fifteen miles so R.J. could see if Melissa Lloyd’s car was in her driveway, and then they drove fifteen miles back to town to R.J.’s house, and then Joshua drove himself another twenty-six farther south to his own house. When he was alone in the car he realized that his jaw ached, that he’d been clenching it without his being aware. He tried consciously to let it hang, as if it dangled from the rest of his face. He did not feel high so much as acutely aware of the edges around him and within him, and he liked that feeling and knew that he wanted to feel it again.

When he pulled into the driveway and got out of his truck, he could hear Tanner and Spy barking their hello barks from inside the house, pushing against the front door to greet him. He hurried in and tried to get them to hush up so he might avoid waking his mother and Bruce. He didn’t turn any lights on and walked quietly into the kitchen and opened the refrigerator to look inside, though he wasn’t hungry. He took an apple and bit into it and then regretted it, but continued to eat it.

“Josh,” his mother called to him.

He could hear her getting out of bed. “I’m home,” he said, irritated, not wanting her to. He considered bolting immediately upstairs. He loved his room.

“You’re late,” she said, appearing in the kitchen, wearing her long fleece nightgown and fake fur slippers. The dogs went to her, forced their noses into her hands so she had to pet them.

“We closed late. Three tables came in right at the end.” He tossed the apple at the garbage bin and could tell by the sound it made that he’d missed, but he didn’t go to pick it up. “We don’t have school tomorrow anyway. It’s teacher workshop day.”

“You’re supposed to call when you’re later than ten. That’s the deal we made when you took the job.”

“It’s only eleven.”

He poured himself a glass of water and drank the whole thing in one long chug, aware that his mother was watching him. “What?” he asked, filling the glass again, running the water hard.

“I’m not tired anyway,” she said, as if he’d apologized for waking her. “You want some tea?” she asked, already putting the kettle on.

“Did you see the moon driving home?” she asked.

“Yep.”

She took two mugs from their hooks above the sink and placed the tea bags into them without turning any lights on.

“The chamomile will help us sleep.”

The kettle began to whistle. She picked it up and poured the water into the mugs and sat down at the table.

He sat too, sliding his hot mug toward him.

“It’s that I worry when you’re late. With the roads being icy,” she said, gazing at him by the dim light of the moon that came in through the windows. “But you’re home safe now and that’s what matters.”

She blew on the surface of her tea but didn’t take a sip, and he did the same. He wore his headphones around his neck. He ached to put them on, to blast a CD. Instead, he imagined the music, playing a song in his head, its very thought a beacon to him.

“So, you were busy tonight?”

“Not really,” he said, and then remembered his earlier lie. “Until just before closing and then the place filled up.”

“That always happens.” She laughed softly. “Every time I’m about to get out of Len’s a busload of people shows up.”

She’d tried to quit her job there once. She started up her own business selling her paintings at flea markets and consignment shops. Scenes of northern Minnesota. Ducks and daisies and streams and trees and fields of grass and goldenrod. Most of them were now hanging in their house, much to Joshua’s chagrin. His mother had taken R.J. on an unsolicited tour of them once, telling him her inspiration for each painting and their titles. The titles embarrassed Joshua more than the paintings themselves. They were indicative of all the things that irked him about his mother: fancy and grandiose, girlish and overstated—Wild Gooseberry Bush in Summer Marsh, The Simple Sway of the Maple Tree, Birthland of Father Mississippi—as if each one were making a direct appeal to its own greatness.

Joshua took a tentative sip of his tea and remembered a game he and Claire used to play with their mother called “What are you drinking?” She’d make them drinks out of water with sugar and food coloring when she didn’t have enough money for Kool-Aid and then she would ask them to tell her what they were drinking, smiling expectantly, and they would say whatever they wanted to say, whatever they could think up. They would say martinis, even though they didn’t know what martinis were, and their mother would elaborately pretend to put an olive in. They would say chocolate milkshakes or sarsaparilla or the names of drinks they’d invented themselves and their mother would add on to it, making it better than it was, making the water taste different to them too. This was before they met Bruce, after they’d just moved to Midden, when they lived in the apartment above Len’s Lookout. The apartment wasn’t really an apartment and the town didn’t yet feel to them like a town, so outside of it they were that first year, not knowing a soul in a place where everyone else knew each other. Their apartment was one big room, with a kitchen that Len had devised for them along one wall, and a shower and sauna and toilet out back. There was a couch that they pulled out into a bed, and they all slept on it together and usually didn’t fold it back up, so that the apartment was really a giant bed, an island in the middle of their new Minnesota life.

In the afternoons when Claire and Joshua had returned from school and their mother was home from work they would lie on the bed and talk and play games they’d made up. They would say that they could not get off the bed because the floor was actually a sea infested with sharks. Or their mother would close her eyes and ask, in a snooty voice that she used for only this occasion, “Who am I now?” and Joshua and Claire would shriek, “Miss Bettina Von So and So!” and then they would transform her. Softly, they touched her eyelids and her lips, her cheeks and her face, all the while saying which colors they were applying where, and from time to time their mother would open her eyes and say, “I think Miss Bettina Von So and So would wear more rouge, don’t you?” They would rub her face for a while longer and then she would ask, “What on earth are we to do about Miss Bettina Von So and So’s hair?” and they would rake their fingers through her hair and pretend to spray it into place or tie it into actual knots. When they were done, their mother would sit up and say, in her best, most luxuriously snooty voice, “Darlings! Miss Bettina Von So and So is so very pleased to make your acquaintance,” and he and Claire would fall onto the floor in hysterics.

Joshua remembered these things now with embarrassment and something close to rage. As a child he’d been a fool. He wasn’t going to be one now.

“What are you thinking?” his mother asked suddenly, suspiciously, as if she knew what he was thinking.

“Nothing.”

“Do you have a girlfriend?”

He could hear that she was smiling and—he couldn’t help it, he didn’t know exactly why—he wanted to obliterate her smile.

“Why?” he asked bitterly.

“I wondered if that’s what made you late.”

“I told you. We got tables that came in.”

The dogs sat between them and laid their paws on their laps every once in a while and then withdrew them when they got petted.

“Plus, if I had a girlfriend, I would be more than an hour late.”

“I suppose you would,” she said, thinking about it for a moment and then breaking into a long deep laugh. Despite himself, he began to laugh too, but less heartily.

She took off her wedding ring and set it on the table and went to the sink to pump lotion onto her hands and stood rubbing it in. He could see her silhouette in the dark. She looked like a friendly witch, her hair pressed up scarily on one side of her head, from how she’d been lying on her pillow.

“Here,” she said, reaching out to him and sitting back down. “I took too much.” She scraped the excess lotion from her hands onto his and then massaged it into his skin, onto his wrists and forearms too. He remembered when he had had colds as a child she would rub eucalyptus oil onto his chest and chant comically, “The illness in you is draining into my hands. All of Joshua’s illness is leaving his body and will now and forevermore reside in the hands of his poor old mother.” He had the feeling that she was remembering this too. He felt close to her all of a sudden, as if they’d driven far together and talked across the country all night.

“Does that feel good?”

“Yeah.”

“I love having my hands rubbed more than anything,” she said.

He took her hands and squeezed once, then let go.

“How was your day?” he asked.

“Fine. I went to Duluth actually. Bruce and I went. We ate at the Happy Garden.” She took a sip of her tea. “There’s something I want you to do for me, hon. It’s a favor I want. Claire’s coming home tomorrow and I want you to have dinner with us so we can all have dinner together as a family.”

“I work.”

“I know you work. That’s why I’m asking now. You’ll have to take the night off.”

“I can’t. Who’s Angie going to find to cover for me?” He held his mug. It was empty, but still warm.

“It’s a favor that I’m asking you to do,” she said. “How often do I ask you for something?”

“Often.”

“Josh.”

He petted the top of Tanner’s head. He tried to keep his voice calm, though he felt enraged. “What’s the big fricking deal about Claire coming home anyway? I see Claire all the time. She was here two weeks ago.”

“Don’t say fricking.”

“Why?”

“Because I’m your mother and I told you not to say it.” She looked at him for a while and then said quietly, “It’s a stupid word. Say fucking, not frigging. And don’t say that either.”

“I didn’t say frigging. I said fricking. There’s no such thing as frigging.”

“Look it up in the dictionary,” his mother said gravely. “There is such a thing as frigging. It’s just not the best choice, comparatively speaking.”

He tilted himself back in his chair as far as he could, so far he had to anchor himself underneath the table with his knee, but his mother didn’t tell him to stop, didn’t even appear to notice. He let it fall back onto all four legs and said, “Ever since Claire went to college it’s like she’s the queen bee.”

“This isn’t about Claire.” Her voice shook, he noticed. “It’s about doing something that I asked you to do. It’s about doing me a fucking favor.”

They sat in silence for several moments.

“Okay,” he said, at last. It was like someone walking up and cutting a rope.

“Thank you.” She picked up both of their mugs and went to the sink and washed them, then turned toward him, drying her hands. “We’d better get some sleep.”

“I’m wide awake.”

“Me too,” she said in a hushed voice. “It’s the moon.”

He stood and stretched and raised his arms up, as if he were about to shoot a basketball; then he jumped and swatted at the ceiling, landing in front of his mother. He patted the top of her head. He was taller than her by more than a foot and now he stood up straighter so he would be more so. The cuckoo clock that Bruce built poked its head out and cooed twelve times.

“Is everything okay?” she asked when the clock was done.

“Yeah,” he said, a wave of self-consciousness rushing through him, remembering the meth. His mother had a way of detecting things.

“Good,” she said, pulling her robe more tightly around herself. “And everything’s going to be okay.”

“I know.”

“Because I have given you and Claire everything. All the tools you’ll need throughout life.”

“I know,” he said again, uncomprehendingly, feeling mildly paranoid about seeming high, especially that now in fact he suddenly felt high.

“You do know, don’t you?”

“Yes,” he said insistently, not remembering what he knew. He felt simultaneously disoriented and yet also in full command of himself. The way he felt when he’d gone to a movie in the bright light of day and emerged from it and found the day had shifted astonishingly, yet predictably, to night.

“And I’ve given you so much love,” his mother pressed on. “You and Claire.”

He nodded. Out the window behind her he could see the silhouettes of three deer in the pasture, their heads bent to Lady Mae and Beau’s salt lick.

“You know that too, don’t you?”

“Mom,” he said, pointing to the deer.

She turned and they both looked for several moments without saying anything.

And then the deer lifted their heads and disappeared back into the woods, which made the world right again.