Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

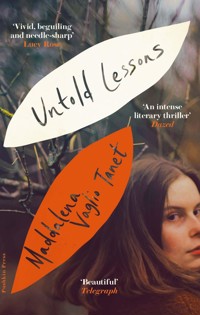

'Vivid, beguiling and needle-sharp. An unmissable literary thriller' Lucy Rose 'Rich and evocative, slippery and strange. I was hooked from the very first page' Chloë Ashby What happens when the missing don't want to be found? One morning, a teacher vanishes into the woods. As whispers fill her classroom, she melts into a shadowy wilderness, where the air hums with ancient birdsong and a blanket of moss covers her tracks. Back in town, the mystery deepens. Who is Silvia really? An inscrutable misfit without a husband, devoted to her students until tragedy strikes. When a young boy stumbles upon her hiding place, it seems the search may be over. But is Silvia ready to return? Praise for Untold Lessons:'Satisfying and deeply felt' Irish Times 'Mysterious and elegant' Veronica Raimo'A strong debut by an emerging novelist and a loving work of restitution' TLS 'Moving and thought-provoking' Glamour Magazine 'One of Italy's most exciting new feminist authors' Service95 'Beautiful. . . a rare study of communal grief' Telegraph 'A book full of upended expectations' Guardian

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 305

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘A dark literary thriller… In her prose, the natural world becomes something out of a fairy tale, escapist and dangerous’

london magazine

‘A strong debut by an emerging novelist and a loving work of restitution’

tls

‘Moving and thought-provoking… delves into the complexities of life’s unspoken lessons’

glamour

‘Beautiful… A rare study of communal grief that continually finds new ways to describe old sentiments’

telegraph

‘A fictionalised retelling of a true incident and a heartbreaking story about individual choices and their consequences’

new statesman

‘One of Italy’s most exciting new feminist authors — a tantalising thriller that will keep any reader on their toes’

service95

‘A powerful exploration of the fragility of the ties that bind us to society and loved ones’

marie claire

Untold Lessons

Maddalena Vaglio Tanet

TRANSLATED FROM THE ITALIAN BY JILL FOULSTON

PUSHKIN PRESS

Untold Lessons

6

In memory of Ada Maurizio, my grandmother Maria Vadori, my great-grandmother, and Lidia Julio, the teacher

For Paola Savio, my mother

7

Stones taut in the woods; they have small

friends, ants and other animals

I don’t recognize. The wind

doesn’t blow away the tombstone, graves, the

shadowy remains, that life of heavy dreams

You remain in shadow: my heart burns

and then crumbles in order to remember naïvely not to die.

My heart is like that forest: wholly

sarcastic at times, its filthy branches

falling on your head, burdening you.

amelia rosselli,Documento

Like eyes these dull holes in the window

on the right the ivy has stripped everything and it seems

beautiful you might say a triumph this greenery

while overhead a bird squawks you see it fly

in circles like someone who speaks to ghosts

what a strange machine, the head, we harass the dead

with our thoughts, caw, caw, it’s only a crow.

azzurra d’agostino, Canti di un luogo abbandonato

Contents

1

Instead of going to school, the teacher went into the woods.

In one hand she held the newspaper she’d just bought and in the other her leather satchel containing notebooks, corrected homework, pens and well-sharpened pencils. She left the road unhesitatingly, as if the woods had been her destination from the start. Her loafers padded over a carpet of shiny brown leaves that looked like raw entrails.

She soon abandoned the satchel and the newspaper; at a certain point, her grip had loosened without her noticing. She followed one path for a bit, perhaps from muscle memory, and then left it and began ascending and descending the slopes. She felt she was going at great speed, and that the landscape was melting around her. Chestnuts, hazelnut trees and birches were splotches, rivulets of colour; the sky spilt over the outlines of the hills; the earth danced under her feet like a floating jetty.

The percussion of her feet on the level ground became a kind of drumbeat, urging her to continue. She heard the impact, but as if it were coming from underground; someone down there was knocking, forcing her to go on, chasing her away. 10

After many hours, tiredness compelled her to slow down. She was stumbling, her lips were sticky with saliva and she kept swallowing in an effort to get something down: it felt like she’d swallowed a bite that had become stuck in her throat, but it was her heart, tired out by the march. Her skirt was streaked with mud, her tights shredded by brambles.

The daylight was fading, by this time almost azure, blue. A half-moon materialized above the mountain tops. The teacher recognized the feeling of the cold night air, and it was that familiar sensation which restored a moment of clarity and allowed her to truly suffer.

She had climbed a hill called the Rovella, and from there she could see the village of Bioglio where she’d been born: the roof of the church, its bell tower, the lights going on one by one in the dusk. She saw them, but she couldn’t understand them. They seemed like the ruins of a forgotten civilization. She had got all the way up there without meaning to, urged on like a blindfolded prisoner. Her stomach was twisting with hunger, the backs of her shoes had rubbed her heels and even her face hurt because she hadn’t stopped clenching her teeth and jaw the entire time. She couldn’t go down to her village, nor could she turn round: the hazy memory of her house and the people she knew terrified her.

She wasn’t afraid of the woods, though. She’d grown up during a time when they were used like fields and pastures. She’d been going there with her cousin from the time she was a girl, at night too, to look for mushrooms. They’d gone out alone in the dark, pitch-black, climbing up the shortest, steepest road behind a clutch of houses clinging to the hill. They had a lamp and two 11sticks for holding back the shrubs and tapping at piles of leaves, a wicker basket with a handle for their treasures. The scent of mould was strong, and they knew how to follow the rot snaking between tufts of grass to find the wild mushrooms. Some of the enormous porcini made them swear for joy. The rest of the time they communicated by nodding and elbowing each other, holding hands only in exceptional cases (a badger too close, a painful slide on the backside, a sprain). They knew every twist in the path, the exposed roots, the eroded earth, the roe deer’s tracks and glades where they stopped to sleep, the abandoned dens of foxes, trunks gnawed by dormice. An ash-coloured dawn arrived with a timid glow, making the treetops seem even blacker. They’d go there to collect chestnuts, too, cracking the burrs under their little boots.

It was October now. There were mushrooms, hidden, and chestnuts on the ground, but it was 1970 and she was forty-two years old.

The teacher turned her back on the village. She was trembling from head to toe, and within her chest she felt the flapping of wings in the branches like palpitations. She had a flickering memory of an abandoned cabin, an old shelter for animals and tools, its roof in a sorry state. She’d just have to drag herself to the top of the hill where the woods had overtaken the paths and bushes and the sweet acacias had suffocated the other trees. She grabbed at the heather to get back up the incline, directing her feet towards the crags.

The roof of the cabin had been cobbled together a few years before with prefabricated tiling, but since then no one had had 12the time or strength to keep back the vegetation. There were no stairs to get to the wooden loft and the branches of an acacia were poking through the tiny window. There was still straw on the ground, not all of it mouldered, and in one corner old billhooks, rakes and sickles.

The teacher staggered on, paying attention to nothing. She was dazed, and her eyes were seeing things that had nothing to do with where she actually was. As soon as she crossed the threshold she fell to the floor and stopped moving.

2

That morning she’d got up wearily, as always. Her alarm clock sat on a small saucer, and she’d placed coins in it so that whenever the alarm went off, clanging and vibrating, the intolerable sound made her jump. She’d turn it off with a slap, eyes still shut; its many tumbles to the floor had dinged and dented it into something unrecognizable.

The teacher would get up and light the burner under her waiting coffee pot. Onlyafteracoffee, she told herself, willIbeabletothink. She’d leave the small empty cup on the table in the midst of the circular prints made by other cups, other coffees drunk over the preceding days.

She’d take off her nightgown in the bathroom and wash her arms and chest, making sure not to neglect any part of her skin because she knew she was careless, and every now and then her cousin’s wife would alert her: ‘Silvia, you should change your jumper. You’ll sweat now that the heating is on.’ She must have smelt of sweat. She didn’t notice it, but she didn’t want to upset anyone, especially the children. With children you had to be neat and clean because they were forced to be well groomed, and if they were found to have a sweaty collar or dirty nails 14they got shouted at. So she had got into the habit of washing with too much soap. Every week she used entire bars of Felce Azzurra and doused her armpits, underwear and inside her shoes with talcum powder. But she remained at one with the countryside, the rake and the beasts, and she knew that one day when she retired she would go back to her village and throw fistfuls of salt over red snails to dissolve them before they could attack her lettuces. She’d sweep up hens’ droppings, repair the rabbit hutch and force herself to remember to wash her hands before she ate.

Outside the sky was clear and the light threw the hillside, trees and buildings into sharp silhouette. At least two people saw her walking down the road that slithered around the incline: Signora Berti, from a window in her house between two medlar trees, and then Giulio Motta, who was having coffee on his balcony with the cat on his knees.

Everyone in the neighbourhood knew the teacher. She had moved to Biella as a young girl for school, and she hadn’t gone anywhere since then aside from a few coach trips to Valle d’Aosta and Switzerland, and to Liguria to dip her toes in the water. She’d taken her one flight to visit relatives in Melbourne, Australia, but she remembered almost nothing of that trip, saying only, ‘It was nice,’ or ‘If they see a kangaroo, they run over it or put it on the barbecue.’ And if someone pressed her on that—‘What do you mean, Silvia? How do they manage to hit them?’ or ‘Poor things,’ ‘But isn’t the car damaged?’ she just shrugged. She often shrugged, was often lost in thought, and she walked with her head down, lower lip protruding, brow furrowed. She looked at 15her feet or at the road ahead of her and her close-set blue eyes remained hidden beneath their lids.

She lived on the edge of the city, where multi-storey blocks of flats with lifts alternated with houses and their gardens, wild meadows, kitchen gardens and chicken coops. Sorb hedges thrust clusters of orange berries out on to the pavements, and even at that early hour piles of dead branches and foliage left after pruning were already burning in courtyards. The smoke hit her sideways, in gusts, while the stench of rotten foliage rose from gutters and ditches. She inhaled deeply and thought that some pungent odours were, after all, agreeable. She liked the smell of cellars and the skin of salami, for example. On the other hand, she hated the smell of milk simmering on the cooker, which she blamed on her years at boarding school, when they gave her sour milk at breakfast, lunch and dinner.

She would hurriedly buy a paper from the newsagent at the bottom of the hill because she wanted to get to class early and finish writing out the homework she’d assigned to her students. She made each child a copy by hand in her clear, neat writing.

Signor Minero in the newsagents didn’t dare say anything and he didn’t stop her. Anyway, he wasn’t sure whether the girl was one of her students. Perhaps Silvia barely knew her. Mainly, he was embarrassed: he didn’t want to be the first to talk to her about it. Clearly, he would have been the first—almost no one knew, it was still early, and she seemed wholly unaware of what had happened. And what if she started crying? Or fell to the ground? 16

While he was mentally trying out a few phrases (Silvia, did yousee?Silvia,haveyouheard?Silvia,wait), clearing his voice and opening his mouth to speak, she went out. She left some coins, the right amount, on the plastic tray and was instantly out of the door.

‘Didn’t she even read the headlines?’ he was asked later.

‘No, she folded the paper in half, shoved it in her handbag and left.’

Who can say whether it would have made any difference if she had discovered what had happened to the girl while she was not alone? She might have collapsed right there in front of them. She wouldn’t have been able to leave like that, on her own, as if nothing had happened. Minero would have taken her home or phoned her relatives: Something’shappened—comeandgetSilvia.Or maybe she would have trembled, hesitated, then pulled herself together, gripped her handbag and said, I’mallright.I’llgotoschoolanyway.Instead she had gone into the woods.

‘I should have stopped her,’ Minero repeated over the following days.

‘That ass, Minero! Why didn’t he stop her?’ thundered Silvia’s cousin, the closest relative she had. He was over six feet tall, and his voice shook the glasses.

‘Don’t shout, Anselmo.’ His wife tried to calm him, unable to bear her husband’s fussing, his theatrical eruptions.

‘He’s a prat! I’ve always said so!’ he went on, shouting like crazy and beating the table with hands as large as spades.

‘That’s enough. You’ll have a seizure.’

‘Idiot!’ 17

‘Oh come on! Why do you care about Minero? We should focus on Silvia. Where might she have gone? Where could she have slipped and fallen?’

‘Quiet, you. You don’t understand a thing,’ Anselmo shouted, and he clenched his fists to squeeze out his anguish.

3

The two-storey school building was the colour of milky coffee and surrounded by a narrow mesh fence, hydrangeas and cherry laurel. The playground was paved over in gravel and cement with insets for grass where little trees were growing, tormented by the youngest children who climbed on them and tore off their leaves to make ‘soup’. It was a fifteen-minute walk from the newsagents.

‘She must have opened the paper on the way,’ they later surmised.

In fact, the teacher had taken the paper from her handbag while she was still walking. She liked to scan the headlines at least before getting to school, to feel more firmly attached to the world. You’vegotyourheadintheclouds,Silvia.You’reoffwiththefairies. People always said that. She shook the paper open and at that moment, by the side of the road, she read the news. She stopped abruptly, seemingly unperturbed, and yet, if one had looked closer, her stillness might have appeared unnatural. There was an avalanche inside her. Almost immediately, she was unable to decipher the characters, but in the rubble of letters a few isolated words continued to pulsate before her eyes: fell, 19body, tragedy. After a minute or so, she turned the page to find the end of the article and a photo of the large block of flats with a torrent, the Cervo, winding below it.

She became aware that she was walking again, her legs carrying her miraculously and without her intervention. She hurried along, like someone late for an appointment, and only now and then did she stumble or her ankle give way. But she couldn’t have said whether she was limping or her shoulder was hurting; she’d brushed against a wall (plaster dust had left a clear mark on her raincoat, or maybe it was chalk from the blackboard the day before). She passed the hospital and let herself be led down the hill. The pavement beside the cement wall was narrow, and the passing cars rattled and shook over the cobblestones.

At the last bend in the road the Cervo and the bridge came into sight, and she realized that her legs were dying to throw her into the water. She had nothing against this plan. It didn’t matter to her, and actually it seemed reasonable, even logical. It would be easy to get over the railing: no one paid her any attention, and no one would get there in time to stop her. But, to her surprise, she covered the entire span and reached the opposite bank as if she were cycling, and in fact she felt a cramp in her stomach because she wasn’t far from the block of flats shown in the paper, and she remembered, momentarily, the tale of the Pied Piper who drowns rats in the river and then drowns the children too, in revenge. She was the rat, but the sequence was all wrong: the rat comes before the girl, not after.

She’d missed her chance and had to go on; she thought she’d 20probably walk until she fainted and that, too, would be fine with her, though it would take a lot longer.

Her eyesight worsened; she no longer recognized shapes. It felt like the woods had come after her, entangling her in a jumble of trunks, spines and foliage.

4

She was never late, so everyone was alarmed by her absence. The news, meanwhile, had arrived at the school as well. The police inspector asked for a meeting with the headmaster and teachers as soon as lessons were finished. A couple of journalists started taking photos of the building just as the children swarmed through the gate. One second-year pupil called out a greeting: ‘Ciao, Uncle!’

It was a small town.

There was an empty desk in class now, and Silvia was nowhere to be seen. They figured she must have found out—someone must have called her, a journalist or a relative up early—and that she hadn’t felt like leaving the house. It was another teacher, Sister Annangela, one of her closest friends, who phoned her apartment. When she got no response she phoned Silvia’s cousin Anselmo, only two doors away. His mother-in-law answered.

‘Good morning, Gemma, it’s Sister Annangela.’

‘How are you? Is everything okay?’

‘Can’t complain, Gemma, can’t complain. I’m looking for Silvia—is she at your place? I understand if she doesn’t feel like coming in today…’

‘She’s not here.’22

‘Oh,’ said Sister Annangela, before repeating, ‘She’s not with you.’ The headmaster in front of her shook his head as if it were mounted on a spring, and another teacher, Fogli, sniffed.

‘But what’s wrong, Sister Annangela?’

‘Maybe she’s at home but isn’t picking up her phone. That could be it. Would you mind checking?’

‘Sure. I’ve got the keys. But you’re worrying me.’

‘Well, Gemma, it concerns a student, a girl in year six, Silvia’s class.’ Sister Annangela’s voice broke despite her efforts. ‘She’s gone. She passed away last night.’

‘Oh, Madonna. Oh, my God.’ Gemma held the receiver away from her ear and looked at it as if it were guilty. ‘How could she have known?’

‘Someone may have phoned her early this morning, or maybe she bought the paper, read the news and went back home.’

‘An accident?’ Gemma asked again.

‘In the Cervo, in the river. We don’t know anything for sure.’

‘Poor dear. May the Lord take her to glory,’ Gemma said. She was very devout and whenever she turned to God her Friulian accent took over.

‘I know, it’s dreadful. A child. Eleven years old. We’re shocked. If she’s heard about it, Silvia too must be upset. It was one of her students. She really looked after her. Go and check, Gemma.’

‘I’ll call you back, Sister Annangela.’

Gemma put down the phone and left the house, her apron still tied and her shoes only half on.

‘They’ll call back,’ Annangela said to the head. ‘I’m going to look in on the class.’23

Her heart sank, for the girl and now also for Silvia. She knew her, knew she wouldn’t be able to bear up under the sorrow. She might seem solid and opaque, like a slab of ice you could walk on without worrying about it cracking. But in fact the ice was thin, a barely thickened membrane.

She went into the year-six class, which was waiting and being looked after by a caretaker with a sombre expression. The students still knew nothing.

Sister Annangela was very short and stout, with feet so small they looked round and calves like two sausages stuffed into the thick brown tights that nuns wore.

‘Be patient, children. Your teacher, Canepa, may have been taken ill. We’re trying to find out.’ She signalled to a girl sitting in the front row. ‘Excuse me, I don’t know your surname.’

‘Cairoli.’

‘Right, Cairoli. Please hand me your textbook.’

She put on her glasses, ran her stubby finger over the table of contents and assigned some reading: TheElephant’sChild.

‘Read the text silently and underline nouns in red, verbs in blue and adjectives in yellow.’

She gave the caretaker a consoling look and went back to her class of second years, small children beaming with unexpected freedom. There, too, a caretaker was monitoring the chatter. One student stood in front of the perfectly clean blackboard with the air of someone who’d had a prickly chestnut burr slipped into his pants.

‘What are you doing there, Martinelli?’

‘I sent him there, Sister Annangela, because he said something dirty about your absence.’24

Sister Annangela felt a smile breaking out and she pressed her lips together hoping to suppress it, at least partially.

‘Crikey! Something dirty. Something I have to hear.’

She didn’t want to embarrass the caretaker by revoking the punishment, but neither did she want to leave the child standing there. Not that day.

‘Not that dirty, Sister Annangela,’ Martinelli protested.

‘He said…’ The caretaker looked for the right paraphrase. ‘He said you were in the loo, Sister Annangela.’

‘Interesting.’

‘Doing your business.’

‘I get it. Thank you.’

‘Sorry!’ the boy blurted out, on the verge of tears.

Theytakeeverythingterriblyseriously, Sister Annangela thought, struck by a wave of sadness. Marina Poggio was scratching inside her ear with the rubber on her pencil. Ludovico Bindi balanced on his knees the apple he would eat during break. Sister Annangela herself tasted salty tears in her throat.

‘You’re excused, Martinelli. Go back to your seat. And anyway, for your information, I wasn’t in the loo.’

She sat down, and for a moment she feared she wouldn’t be able to face the morning or the days to come. The funeral. She hung her head. The children looked at her. ‘Crikey,’ she said again, and their eyes widened like those of a row of little owls. She’d have to move them into the other second-year classroom and go back to the girl’s class, where they were still reading TheElephant’sChild, completely oblivious. They had no idea.

5

Gemma rang the bell and knocked again and again without an answer. She put her ear to the shutter but heard no noise. Then, steadying her hand, she opened the door to Silvia’s house.

She was used to emergencies. She knew the tension that lashes the body like a steel cable. She was from Friuli, where she’d been born in 1903. Whenever anyone talked about the Second World War she’d say, ‘Just think: I’ve been through two of them.’ She enjoyed saying that. She enjoyed the fact that she was still alive despite the Battle of Caporetto, the Spanish flu, widowhood, bombs and the German round-ups, though many people she knew felt guilt more than anything else. Her daughter, Luisa, for a start. But for Gemma the past was just that: it was behind her, gone. Iwon’tendupfleeingatnight,Iwon’tgetacrossthebridgebyawhiskerbeforeitblowsup,mydaughterwon’tbesenttoGermanytoworklikeaslave.She maintained that this was all anyone needed in order to live optimistically.

Yet that morning, when she found Silvia’s house empty, Gemma was overcome with an inexplicable sense of danger. It was too early to become alarmed. Silvia couldn’t have left much more 26than an hour ago: the coffee grounds in her cup were still wet, her bed was unmade, the soap had slid on to the green tiles of the bathroom floor. The teacher wasn’t your typical housekeeper, so nothing strange about that. But as for being there: she wasn’t. Gemma promptly phoned the school to let them know.

6

While she’s sleeping, something rips open her stomach. She is the one doing it. She scrapes away the pulp with a knife, as if peeling a medlar until only the shiny kernel is left, a strange contrast with the fruit. She sees it glowing like a little black sun, a rejected black egg. A hollow Easter egg, nothing inside.

The teacher opens her eyes. As soon as she closes them the images appear. The ribs of a calf, a mole drowned for tunnelling through the kitchen garden, billhooks on the cellar wall, a frog’s pulsing throat, which you can puncture with a needle or chop off: you draw a line with a knife, the way you would underline a word or cross it out to correct it. She sees mountains of notebooks with all the words crossed out, a dusty classroom, but maybe the particles in the air are ashes, and she finds herself in an empty fireplace—enormous like the one in Verrès Castle, which she has visited many times with her classes. Yet no, that can’t be, because her grandmother is dragging her feet around the room there. Silvia hears the rustling of her slippers and petticoat. A man carries a pheasant over his shoulders, head dangling, eye cloudy. An obese woman heads towards the loo at the back of 28the courtyard, looks around and pulls up her skirt; because of her bulk, she can’t get all the way into the poky room and part of her is forced to remain outside. Trembling with the effort not to topple over, she grabs the frame of the gaping door. She doesn’t know that a few young boys are climbing up on the pergola to steal grapes, and now, laughing, they watch her from above. She doesn’t know it, but Silvia hears their muffled cackling.

The more violent her visions, the more they calm rather than scare her. Not far away, boars grumble. A blackcap whistles; it must be nearly morning. She doesn’t formulate this thought, but her ears register the sound and inside her something answers: blackcap. It’s a reflection more than information and is soon forgotten. Her senses bring her material, her brain tries to function, but it’s all a black sludge of indifference.

Through the door of the hut Silvia makes out a birch tree with its fruit. The image slams into her and she is tempted to use her arms to shield herself. The fruit of the birch look like little brown salamis dangling there. They crumble into powder on first contact, releasing their seeds. Anything that droops, leans or hangs from a hook is fine by her. She herself feels like that, a bundle hanging by the waist from a skinny stem, which might also be a noose. Above her head the crooked roof reveals patches of the sky, growing ever brighter.

Outside is a beech whose bark has been colonized by bracket fungus: dozens of ash-grey hats protrude from the trunk like hoofs. The bark is already flaking off; large slabs of it are missing. Silvia knows there’s no escape for the tree: sooner or later it will fall. She knows this, but nothing is organizing itself in a 29coherent whole, into before and after, and anyway she doesn’t see any great difference between herself and plants with their parasites, mould on planks, living animals and their carcasses, the breeze coming through the door and cracks. She needs to urinate but doesn’t see why she should get up, go outside and do that like the fat woman mocked by the boys’ excited gaze. She empties her bladder right where she is, not moving an inch.

7

Giovanna: that was the girl’s name. At the end of the previous year she’d started skipping class. She’d never done very well at school; she was slow.

‘What’s this all about? You can’t afford to stay at home,’ Silvia told her. She kept her back after class and did her homework with her. She sat beside her, ill at ease yet determined, meanwhile unwrapping the sandwiches she’d prepared for the two of them. They were the only thing Silvia made in her kitchen other than coffee, since she always ate supper with Anselmo and Luisa. Mostly she put slices of cheese in those sandwiches, because she’d noticed Giovanna preferred that, or butter and jam.

‘Everyone gets better with practice. Look at me. I’m not that bright, but I made an effort.’ She said it without false modesty. It was the truth, and it had to be faced; she wouldn’t take compliments. Silvia felt she was at least intelligent enough to know that she wasn’t a genius. A completely normal brain, a dash of perseverance, diligence. At boarding school, where she’d studied after the war, the good ones were the others, girls who learnt without trying, knew things instinctively or made them up. But not her; she did what she had to. She had a sense of duty and 31determination, an awareness of being too awkward and insecure to carry the weight of being considered a dunce. As an orphan, she’d grown up with her grandparents, and ended up in boarding school. She couldn’t bear being told off or humiliated because of her performance at school.

‘Come on, Giovanna, let’s do your homework together. That way you’ll be set for tomorrow.’

‘Thanks, Miss,’ the girl replied. And then she was quiet because her mouth was full.

Giovanna’s parents were herders who had moved to Biella a few years before. Her mother shuttled back and forth from the shepherd’s cottage in the Elvo Valley, where her sister and brother-in-law still lived. Their children went to school in the village of Bagneri. There was only one class and desks and benches were pushed together to form a single block of dark wood, like the pews in church. Giovanna, too, had started elementary school there, but in December she’d caught pneumonia, was admitted to hospital and missed nearly three months of school. When she’d stepped back into her classroom, still exhausted and having lost weight, she didn’t remember any of the standard Italian her teacher had taught her.

That same year her father had found work in a textile factory, an industry that had exploded after the war and was still growing. He didn’t like it but he had a decent salary, his children could go to school in town and they had an indoor loo, even a bath and a washing machine. The washing machine was a second-hand Candy Superautomatic 5, barely dented by the hail that had fallen on it during delivery.32

All over, people were leaving their villages and valleys and Giovanna’s father left too, but he was unhappy and embittered. Like everyone else, he drank and held it well: a bottle a day was nothing for him. Yet every now and then he overdid it, added a little grappa or ratafia. He missed the haystacks, the rattling of the dog’s chain at night, cows with their long eyelashes, even the steaming manure on frozen, trampled grass. He inflicted his dissatisfaction on others. He groped his wife roughly in bed and wouldn’t stop even when she complained or the children in the next room mumbled in their sleep. Giovanna had failed at school and started over in year one, but she continued to get poor marks. Her father’s method of discipline was to hit her, never systematically, never for long. But his calloused hands left bruises that took weeks to fade.

Giovanna was fed up with being hit and she tried hard to make a good impression on her new teacher in town. With great effort on both sides she got a pass mark, but once left to herself she’d started to sink. She’d been about to fail the third year but Silvia hadn’t felt like handing her over to another teacher so she’d pulled her along with her, raising Giovanna’s marks for drawing, PE and crafts.

Something changed at the end of her fourth year. The girl became cheeky but also more sensitive. At times her eyes blazed with bewilderment: she’d started growing body hair and her breasts were developing. She used her fingers to hide the moustache sprouting under her nose; when she saw it in direct light from the bulb over the bathroom mirror, it reminded her of the film of mould staining the corners of the ceiling grey.33

Although she feared Giovanna’s father’s reaction, Silvia had not managed to prevent her getting a string of low marks. ‘Two more smacks, Miss,’ Giovanna commented laconically.

The family lived in a large council block called the Big House, which loomed over the Cervo between factories that had used hydraulic energy to wash wool for a century and a half. Concrete pillars and cement castings alternated with red-brick arches and the smokestacks of eighteenth-century mills.

The Big House was teeming with children and teenagers and some of the boys had begun to stare at Giovanna, which made her feel dirty but important. She didn’t know whether to strut her stuff or run away. Two of them, Michele and Domenico, didn’t only look and whistle; they spoke to her in dialect, acting tough as if they were already grown men. Like Giovanna’s, their bodies manifested the inconsistencies of puberty. She had two little mounds sticking straight out of her chest, seemingly ready to puncture her T-shirt, and two tufts under her armpits, but her behind was still flat and her hips were barely outlined under a child’s egg-shaped tummy. They had enormous hands planted at the end of fidgety arms, Adam’s apples like nuts caught in their throats, a few sparse whiskers on their chins but hopelessly smooth necks and cheeks.

At first, Giovanna didn’t answer them. She was stupefied with embarrassment, and her field of vision shrank to a square floating in front of her feet as she tried to avoid them, turning at the first possible corner and taking the stairs two at a time so she could disappear. As soon as she was beyond their reach she felt herself buzzing with nervousness and her heart pounded—yet it made 34her afternoons more exciting, and the following day she’d offer to go and ask a neighbour for some washing powder or stand on the landing for no reason, hazard a trip to the courtyard where she walked up and down, head bowed, pretending she’d lost something just to see if those two would talk to her.

Silvia sensed the significance of the change but couldn’t keep up with it. A spinster nearing old age, she was treated as a nun by all. Whenever she thought about herself she imagined a plant-like organism, a body less chaste than indifferent. She tried to scold the child. ‘You’re distracted! I can’t do everything for you myself. Come on, so we can finish quickly. Pay attention, or I’ll have to give you a really low mark. Giovanna, you’re not listening to me.’