9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

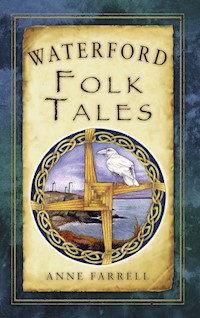

The mountains and spectacular coastline of County Waterford are rich in traditional stories. Even today, in the modern world of internet and supermarkets, old legends dating as far back as the days of the ancient Gaelic tribes and the carvers of the ogham stones are still told and are gathered here in this unique collection of tales from across the county. Included here are tales of well-known legendary figures such as Aoife and Strongbow, St Declan and the three river goddesses Eiru, Banba and Fodhla, guardians of the rivers Suir, Nore and Barrow, as well as stories of less well-known characters such as Petticoat Loose, whose ghost is said to still roam the county, and the Republican Pig, who was unfortunate enough to become caught up in the siege of Waterford. In a vivid journey through Waterford's landscape, from the towns and villages to the remotest places, by mountains, cliffs and valleys, local storyteller Anne Farrell takes the reader along old and new roads to places where legend and landscape are inseparably linked.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to the memory of a beautiful soul and brilliant mind, my lovely daughter-in-law Elaine, wife and soulmate of Brendan and mother to Rory and Eimear

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Aoife and Strongbow

2 Petticoat Loose

3 The Three Sisters – The River Goddesses

4 Famine Stories

5 The Well and the Golden Dragon

6 How Coxtown was Named

7 Iompar á Mhála – The Bag Carrier

8 Mrs Rogers’ Dream Comes True

9 Curraghmore Estate Stories

10 Famous Outlaws

11 Rockett’s Castle

12 The Story of Dunhill Castle

13 An Bídeach

14 Slabhra na Fírinne – The Chain of Truth

15 Prince Sigtryg & King Alef’s Daughter

16 The Story of St Declan in Ardmore

17 St Declan’s Miracles

18 ‘Riann Bo Phadraig’

19 Little Nellie of Holy God

20 Mount Melleray

21 Master McGrath

22 The Speaking Stone

23 The Fenor Melee

24 Pickardstown Ambush 1921

25 The Seahorse

26 The Croppy Boy

27 Lackendara Jim

28 The Wellington Bomber at the Sixcrossroads

29 The Republican Pig and the Siege of Waterford

30 The Tunnel Beneath the River Suir

31 Hans Muff

32 St Cuan’s Well and the Sacred Trout

33 The Glas Gaibhneach

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My grateful thanks to Liam Murphy, master storyteller, for all his help and encouragement; Julian Walton, folklorist; the late Denny Maher; the late Patrick and Eileen Kirwan for keeping tradition alive; Lord Waterford; Breda Mears; Noel McDonagh; Richard Power; Christy Brophy; the late Michael Carberry and the Ballyduff Parish Council; Mary the Memory; Jack Burtchaell; Portlaw Heritage Centre, and to all the other people who gave me their time and kindness.

Thank you – Diolch yn fawr – to Myles Pepper, Jane and Gethin Griffiths, for making the Wales/Waterford connection possible.

My thanks also to neighbours Elaine Mullan, Ian McHardy and Hazel Farrell who kept me on track.

Finally thanks to my family and particularly my lovely husband Brendan, who has been patience itself since the start of this project.

INTRODUCTION

I was born into a family who always told stories, so I had no choice but to be aware of that other life which dances just out of sight.

Storytelling is a delight to the soul for it shifts and changes like the wind and what you started out to tell, more often than not, will end up being a different story altogether.

Sometimes when you sit in front of an audience the stories you planned to tell do not seem right. I never know until I get there what to tell. It is something subtle in the relationship between audience and storyteller. I have always been lucky in my choices when I trusted my instinct. Many times people have come and thanked me because they believed that the story was not only for them but about them. Life is wonderful.

When you think you know a lot about storytelling, you can be brought back to earth with a bump. Many years ago I did storytelling tours in Wales with Liam Murphy and we visited a Community Care Home in St David’s regularly. When we returned one time, after a year away, a young man called Christian asked if he could tell his story, as he had been practising for the whole year. We gladly moved over and he sat between us. His telling of his own story, from the first time he came to the home up until the day we came telling stories, nearly broke our hearts. A speech impediment hampered him but he wanted to let us know that we had changed his life. Everyone cried and rejoiced at the same time. A whole year spent practising one story totally amazed us.

Everyone has a story, if you only take time to listen.

One of the most startling things I discovered when I began writing this book was that local stories are bred into the bones of us. There is no ‘source’, as demanded by academia; we have just known them since we were children at our parents’ knees.

The stories in this collection are about many different areas in Co. Waterford and it has been a joy to chase them up. Some are tales I regularly tell and have a fondness for. An Bídeach and Slabhra na Fírinne – The Chain of Truth are favourites in the country areas while in the city people like Aoife and Strongbow, Crotty the Highwayman, The Tunnel beneath the Suir and The Republican Pig. It is all a matter of what you can get your imagination working on and local knowledge is a great spur.

I always ask for guidance before telling a story and firmly believe that I have a host of helpers nudging the right story to the forefront of my mind. Amergin, mentioned in The Three Sisters, was a druid and bard and is always on the edge of my thinking. What a book he could have written.

Storytelling is different from reading or writing a story, and I have told these stories in the manner of ‘telling’. I hope it does not mar your enjoyment. Put your own blás on them and swing them this way and that in your mind. Let the voices you hear be of your own creation.

One

AOIFE ANDSTRONGBOW

This story began in another county but has always had a place in the hearts of the people of Waterford. That it is based in historical, traceable fact makes it all the more real and special. The River Suir, which Aoife saw when she came here, still flows by the city quays. Standing on the end of the quay, near the Tower Hotel, is Reginald’s Tower, which must have loomed large before her, the day she first came to Waterford.

Her feet touched our streets, even as the blood of our ancestors stained them. She was a frightened, beautiful princess, promised, as part of a military alliance, to a man old enough to be her father. The story runs like this.

In and around the years 1157 and 1167 there was a king named Dermot MacMurrough Kavanagh, ruling the kingdom of Leinster. He was a strong and ambitious king and he dearly wanted to be made king of all Ireland. At that time there were many small or petty kings but the four provinces of Ulster, Munster, Leinster and Connaught had greater kings and ruling over the whole lot of them was Ruairi O Connor – the High King.

The Brehon Laws existed then and there was a law covering every circumstance that could possibly arise in any human relationship.

For a king to have several wives was not uncommon, for didn’t it mean that the people of their clan would have to help him in times of difficulty. But it was not just that, there were laws which governed how much ‘honour price’ must be paid to the first wife or ‘ceit muintir’, when he brought in a second wife and so on. Then everyone settled down and the women got on with their lives, quietly ruling their roost, or sometimes not so quietly. But the system worked.

Well it happened that while Dermot was young he had a close friendship with a beautiful girl called Dervogilla. Now Dervogilla came from the Maolachlann clan and they were close allies always of the MacMurrough Kavanaghs, indeed her own brother fought alongside Dermot in most of his battles.

It was the practice at that time for kings to make alliances of political necessity, which usually meant marrying off their sons or daughters into suitable strong kingdoms. Dermot was no different from any other king in this – he had made a marriage with Mor O Toole so as to have strong connections with her clan, and a little while later to Sive O Faolain from a small kingdom, which controlled a section of land between himself and the O Tooles. He was paving his way to High Kingship, he thought.

Well, Dermot was not an easy neighbour for any king and there were often skirmishes between them but it was not until Dermot decided to rescue his old friend Dervogilla Maolachlann from an unhappy marriage to Tiernan O Rourke that his troubles really began.

Now according to the Annals of the Four Masters and other historical records, Dermot was fully to blame, but I am not inclined to believe them, nor indeed are many other modern historians. It was easy for the Church to make Dermot the villain. He was foolish, in a lot of his ways, thinking he was above the law. Sure, didn’t he cause the Abbess of Kildare to be raped so that he could put one of his own relatives into power there instead of her? The Abbess had rule over the monks as well as the sisters at that time, so it was a powerful position.

Well, to get back to my story. It appears that Dervogilla had made arrangements with Dermot and her brother that they should spirit her away from her unhappy marriage to Tiernan O Rourke. She was party to the plan, for don’t those same records tell us that she had all her goods and chattels ready and waiting for them, when they came in the dead of night and took her back to Leinster.

Now it is also recorded that she cried out for help as she was taken away, but why wouldn’t she? If things went wrong she needed a way back. If she had to come back, through whatever cause, she could always claim she was kidnapped. But the fact is that she went to Leinster and spent almost two years living with Dermot, having paid ‘honour price’ to his first wife Mor, and his second wife Sive, and the three women were very fond of one another, apparently.

Now Tiernan O Rourke was not idle while these years were passing, and in fact all the religious men of power turned against Dermot, so he had more trouble on his hands than he could handle. His two sons, Eanna and Conor, were taken as hostages to ensure his good behaviour, by the High King, and Dermot was in serious trouble because he refused to pay an ‘honour price’ to O Rourke for the taking of his wife. Had he paid that he might indeed have become the High King, but he didn’t and war raged up and down the borders of Leinster.

It was only when his lovely son Eanna, who would have ruled after him, was sent home to him blinded that Dermot realised his mistake. A man with any imperfection, especially of the physical nature, could not rule a clan. But Dermot would not give back Dervogilla and it was only when his kingdom was finally being overrun and the head of his son Conor was sent to him that he gave in. Dervogilla had to go back to O Rourke and Dermot had to flee to Wales, but he took his daughter Aoife and her female servants with him.

Between the two of us, I don’t think that going back to her husband lasted long either, for it is said that she entered Mellifont Abbey, shortly after, God help her. She was probably very glad to do that. I wasn’t there so I don’t know, but by the sound of things he was a terrible man.

The women of Dermot were left behind to take care of things, with his half brother, Murrough, who helped to quiet things down. It was Dermot’s intention to ask for help from King Henry II but that king was busy fighting in France and it was almost a year later that Dermot finally caught up with him at Aquitaine. Things didn’t really favour Dermot at that meeting, but he did get a letter from the king to take to an out-of-favour earl back in Wales.

He hurried back to Wales and together with Aoife, journeyed to meet Richard de Clare, Earl of Pembroke, otherwise known as Strongbow. No one else would help them. They were all afraid of their own king Henry and watching their own positions. It was common practice then for mercenaries to be hired by Irish kings to fight in Ireland and in turn Welsh kings hired Irish mercenaries. There was nothing new in this seeking aid from across the sea.

Well anyway, Strongbow turned out to be a man as old as Aoife’s father, but Dermot promised Strongbow that, if he would help, he could not only marry his lovely daughter Aoife but he could have the kingdom of Leinster, on his death, also. Now that was not his to give, but either Strongbow knew and took the chance, or he didn’t know and badly wanted the alliance.

When the lovely Aoife saw this old man and heard her father negotiating, she was mortified. How could her father do this to her, and worse still how could he belittle himself in this way? Strongbow met her eye more than once and even went as far as offering her wine himself. She trembled as their hands touched, when he steadied the goblet, but lifting her dark eyes to the grey of his she saw understanding and sympathy. This shook her more than anything else. Later, when her father was well in his cups, Strongbow sent his women to her, to show her to her rooms.

The deal done, Dermot returned to Ireland in the early summer of 1167, on the pretence that he was going to incarcerate himself in the Abbey in Ferns with the monks. That was common enough in those times, when men wanted to duck out of their duties. Now that was an easy thing for Dermot to announce, for who knew which monk came and went, from there, under a cowl.

Mor welcomed home her daughter and she and Sive listened to all she had to tell them about the man Strongbow and the proposals her father had made. Aoife described Strongbow as being very tall, with a nice face and freckles, and his eyes were grey, but he was very old. Worst of all had been the promises her father had made. Mor shook her head and laughed. Dermot was trying it on with the man, she said. He probably intended to kill him once he had regained the kingdom of Leinster. She knew her man well.

Aoife knew she should be happy about this but there was something in her that went against it. She took to riding out to the cliff tops, facing Wales, and watching to see if the ships bearing Strongbow might come. More often than not, the wind was in the wrong direction. The poor child had a path of her own worn along the headland before long.

Sometimes she would sit with the women and they would tell her how she might please her husband, when he finally came, for they were sure it would not be long now, and they used their skills with needle and loom to make the necessary bridal wear.

Often and often, Aoife began to wonder if Strongbow was going to come at all, and this would change her mood. Sometimes, she was the proud princess going to do her duty, and other times, she was doubtful, thinking that maybe he did not desire her. It was three years later, in 1170, when her husband-to-be finally came, in the month of August. When the ships were sighted, passing along the coast, it was only then Dermot came out from under his monks cowl. Then he rallied his women and men.

Mor and Sive prepared Aoife, whispering advice and laughing, sometimes sad and sometimes joyful.

A messenger came from Strongbow, who had landed at Passage East, in Co. Waterford, and had gone swiftly up to attack that city, without waiting for Dermot. Dermot must have been greatly annoyed but he had made promises and now he must keep them.

That grand Viking city of Waterford, or Vaderfiord, as they had named it, had stood firm, at first, against this attack until Strongbow’s man, Raymond le Gros, had discovered a little, lean-to house on the outside of the city wall, by the river. He had sent in men to knock down this house and as it fell away into the river, a big chunk of the city wall fell with it. Then it was an easy matter to flood into the little hilly streets of Waterford, bringing blood and slaughter.

Aoife rode with her father and his men. They could see the smoke and hear the sounds of battle, even before they reached the banks of the River Suir. The only building which stood out strong in the smoke-filled air was the tower that was called Reginald’s Tower. It stood down close on the bank of the river, and so it still stands there this very day. Everything else was shrouded in smoke. Seagulls, rooks and ravens circled over the devastation. Ships burned in the harbour. Screams and cries of terror echoed intermittently on the air. Strongbow had descended on that city with little pity.

It is said that Dermot and his wedding party crossed the river, wading through the dead and dying, while Strongbow and the Normans still fought and pillaged. That may be so, but they probably crossed the river near Passage East, and came in along the road that runs up beside the river from Passage. We have no way of knowing.

There, Dermot presented his daughter, as promised, to his new ally, Strongbow, and they were married. She, according to that pompous man Geraldus Cambrensis, ‘was radiantly beautiful’, and why wouldn’t she be, all young girls are beautiful, but the cratur must have had terror in her heart that day. Maybe her father had regrets, but maybe not. Waterford had fallen to his new son-in-law and Dermot was back on his feet again.

Now things did not work out as Dermot expected. Aoife seems to have loved Strongbow and they had a good life. She never attempted to ‘repudiate’ him, as she could easily have done under the Brehon Laws. We should never have let those laws go, we could do with them badly now.

Aoife filled the role of advisor to her husband. She knew the lie of the land and what would work in the way of alliances. They spent time, always battle ready, in Waterford, Wexford and Dublin, if the old tales are to be believed.

She prevented her father from trying to kill him, and she and Strongbow had one daughter, Isabelle, who, in turn, married William le Mareschal, Earl Marshal of Ireland. They had many sons and daughters and they all made good political marriages. One of these marriages, it is reported, resulted in the lineage which leads down to the present-day Queen of England, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. You never know what way your children will turn out in the end.

In Waterford, we like to think of Aoife as one of our own, after all wasn’t she married in our city, and she only a young princess. She was strong and brave and must have been glad to get away from her father and his plotting and planning. She lived for many years after Strongbow and although there is a tomb in Christ Church in Dublin, where it is said Strongbow is buried, other sources claim that he is buried in the churchyard in Ferns, in Co. Wexford. My belief is that there are as many endings to their story as there are scribes who write about it.

Two

PETTICOATLOOSE

When I was a little girl, growing up in the 1950s and ’60s, it was often and often that I would hear mention of Petticoat Loose. Sometimes a girl would be told to ‘tidy herself up’ and not go around like Petticoat Loose. Over the years, my own parents and visiting neighbours might compare a young woman who was not conducting herself as they thought she should to Petticoat Loose or as the local saying went ‘She was a right streel, like Petticoat Loose’.

The story of Petticoat Loose was only told when the little ones had gone to bed. So, for a long time, I did not get the rights of it. However, we had a lovely neighbour named Denny Maher. He had been a friend to my parents since childhood and it was from him I finally heard the tale, as he knew it.

I was working in Tramore, at the time, and telling Denny how I used to cycle from there to my home, some twelve miles distant. Denny drew in a sharp breath and said that I was a foolish girl to be on that road, between Waterford and Tramore, on a dark night. I made light of it, thinking he was just joking me but he wasn’t. ‘Did you never hear about Petticoat Loose being on that road?’ says he.

‘Ah go away now Denny’, says I.

Before many minutes were out, however, I knew more than I wanted to know about that stretch of road, halfway between Waterford and Tramore. There is a part along there where a little bridge turns off, and it was near this place that the dreaded Petticoat Loose was often seen. What she was doing there the Lord only knows, but I believe her spirit roamed over the whole of Co. Waterford. Honest to God, wouldn’t it make you wonder about the after life, the carry-on of some ghosts.

Her name was, according to Denny, Mary Hannigan and she came from the townland of Colligan, outside Dungarvan. She was a fine lump of a woman, bless her, and she could turn her hand to any work on the farm where she grew up. Better than two men, ’twas said. Most of all she loved to dance, and she was a great dancer; not every big woman is, but Mary Hannigan had music in her very bones and she attended every house dance and gathering in the surrounding areas.

Well it is through the dancing that she got her name, Petticoat Loose. It was the fashion then for women and girls to wear layers of clothing, not like now, God help us. One of the staple garments was the petticoat, which could be like an under skirt or indeed a full slip-like garment. Well, for the dancing it appears that a flouncy underskirt was the petticoat in question and Mary swirled around the floor, skirts flying and feet tapping, like none other until disaster struck. Didn’t the petticoat come loose, and came away down around her ankles. Sure she must have been mortified with embarrassment, the cratur, which was made worse by the titters and giggles of those present.

Something was said which aggravated Mary, to the point that she let fly with a fist and a bit of a tussle ensued. Ever after she was called Petticoat Loose, and there was no getting away from a name put on you, in a country place, for a thing like that.

Despite the name there were many who wished to marry her, but she was not inclined to take up with any of them. The one who finally won her hand was the son of a neighbouring farmer. He too was, by all accounts, a fine strapping lad. There must be something in the air around Colligan.

They were married and settled down together without too much fuss or bother, in the beginning, but among the other suitors who had chased after the single Petticoat Loose, there was another man who believed she should have married him instead.

They say that he was a hedge school master, who came and went in the area. He was daft about her and they must have kept up their relationship when they could manage it.

Well things were not going too well on the farm and there were often complaints from people who got milk from them, that it was watered down, and that it had a blueish hue to it.

There came an evening when Mary Hannigan and a servant girl were milking the cows and on the evening air came the sound of a man calling out in grave distress and a sudden cry. The serving girl leapt up to run and see but was knocked flat by a blow from the milking stool thrown by Mary Hannigan. The girl said after that she got a terrible fright and hurt bad, her poor head spinning. She was afraid for her life. Petticoat Loose stood over her as she lay, stunned, in the milking parlour. She told her to get back to the milking and mind her own business.

Sure the little girl was afraid to do anything but what she was told. She had her own thoughts on the matter and it came as no surprise to her to find that farmer Whelan was nowhere to be found in the days that came after.

When people asked Petticoat Loose where her husband was she replied that he had gone away often before and he would come back some time. No more than that would she say.

In a small rural community, talk will always run away with itself and in no time at all it was put about that she had enlisted the help of her lover, the hedge schoolmaster, to kill her husband and dispose of his body. Those who used to work on the farm drifted away from her, she was so contrary, and she did little or no dancing now, only drinking. ‘Bless us and save us’, they said, ‘she would drink like a fish’. Some said she was really a witch and in those times people were ready to believe anything. Some still do to this very day. Well, whether Petticoat Loose was a witch or not, it was her fondness for the drink that finally did for her.

She was in the habit of challenging the men to drinking contests and it was during one of these awful sessions that, after consuming a gallon of beer, she suddenly fell over, stone dead.

It was normal then, and indeed now, to call a priest or some member of the clergy to attend at a sudden death, but no one called either priest or deacon to come, to officiate over the remains of Petticoat Loose. Not even for her burial did a religious attend. They buried her without benefit of Church or people. I often wondered about that. Was her death natural?

Well, life in the area settled down into normal humdrum activities and all was well for about seven years. Now the importance of seven in country superstitions is well known. Sure don’t we still hear about men getting the seven-year itch?

It happened this way. There was a house dance in the locality and as we all know, at that time there were no inside loos, only a little lean-to houseen at the side of the barn. This is where the men would dash out to when the need arose. Well it appears that around twelve o’clock at night one of the young bucks went out to, as they say, make water. He was barely gone out when he came back in, and his face like chalk and the life nearly gone out of him.

‘She is out there’, he said, ‘Petticoat Loose is out in the yard’. Sure they all burst out laughing at him and gave him a stiff whiskey. Soon after that another young fellow went out, on the same errand, and he too came bolting back in and the whites of his eyes showing, like a startled horse.

‘She is out there’, he said, and this time no one laughed. They were all afraid, you see, afraid to go out into that dark night in case they too might see the spectre of Petticoat Loose. So they stayed where they were until daylight came. But the rumours went out and after that there were many sightings of Petticoat Loose, in and around the county.

Some of the sightings were more frightening than others, and many said that if you were travelling alone at night then she would stop you and beg a lift. Because she always appeared as a frightened woman, most people would agree to give her a lift and invite her to sit up on the pony’s trap. (They had no motor cars in those times, only horse or pony and trap, or even ass-drawn traps.) Well, if she sat up on the side of the trap, more often than not the poor animal drawing it would start to falter or not be able to move at all. She would laugh and vanish, leaving both driver and animal spooked so much that they would never be right again.

One night she stopped a man on the Tramore road, near that little bridge, and asked him for a lift. Thinking nothing of it he said ‘Surely, let you sit up on the trap.’ She did, bless us and save us, and no sooner had she rested on it than the poor horse began to falter.

The man said, ‘I don’t know what ails him at all’, and she laughed a horrible laugh. ‘Look at me’, says she. ‘This arm weighs a ton’, and she plonked her right arm heavily on the trap. The animal struggled to keep going. ‘Now look at this arm’, said she holding up her left arm. ‘This too weighs a ton.’ The poor driver was wide eyed with fear now and the trap was groaning and creaking. ‘No more,’ he cried out. But she said, ‘Look at this leg, it weighs a ton’.

The trap came to a standstill and, speechless with terror, the driver watched as she raised her second leg and placed it into the trap. ‘This leg weighs a ton also,’ said she. And lastly she clasped her hands on her belly and said ‘and this too weighs a ton’. At that the trap broke into smithereens and the man fell in a dead faint. It was the horse running, with the ruined trap behind him, that raised the alarm.