Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

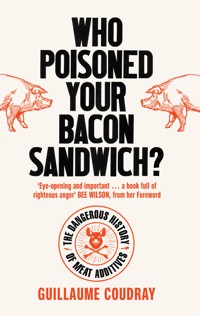

'Highly persuasive ... a well-organised and solid dossier that alerts us to legalised chemical trickery' Joanna Blythman, The Spectator 'A bombshell book' Daily Mail 'Eye-opening and important . . . a book full of righteous anger' Bee Wilson, from her Foreword Did you know that bacon, ham, hot dogs and salami are classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as 'category 1 carcinogens'? Would you eat them if you knew they caused bowel cancer? Following ten years of detailed investigation, documentary film-maker Guillaume Coudray presents a powerful examination of the use of nitro-additives in meat. As he reveals, most mass-produced processed meats, and now even many 'artisanal' products, contain chemicals that react with meat to form cancer-causing compounds. He tells the full story of how, since the 1970s, the meat-processing industry has denied the health risks because these additives make curing cheaper and quicker, extending shelf life and giving meat a pleasing pink colour. These additives are, in fact, unnecessary. Parma ham has not contained them for nearly 30 years - and indeed all traditional cured meats were once produced without nitrate and nitrite. Progressive producers are now increasingly following that example.? Who Poisoned Your Bacon Sandwich? - featuring a foreword by acclaimed food writer Bee Wilson - is the authoritative, gripping and scandalous story of big business flying in the face of scientific health warnings. It allows you to evaluate the risks, and carries a message of hope that things can change.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 644

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

Praise for Who Poisoned Your Bacon Sandwich?

‘[An] eye-opening and important exposé … I couldn’t put it down. It read[s] like a detective story unravelling a conspiracy against the eaters of the world … a book full of righteous anger.’

BEE WILSON, from her foreword

Praise for the French edition

‘This investigation is a service to public health: its strength and originality lie in the author’s deconstruction of the extraordinary web of manipulations, factual distortions, propaganda and doubt manufacturing, which have enabled industrial meat-processors to keep using chemical additives that should have been banned if regulations on carcinogenic substances were simply enforced.’

Le Monde

‘An indictment, a very good investigation into industrial processed meat, which is now declared “a proven carcinogen”.’

Le Figaro

‘[A book] that reveals the dark side of ham.’

Le Canard Enchaîné

‘For several years, Guillaume Coudray has been investigating the nitro-meat industry. His book reveals the underpinnings of a scandal, of which people on modest means are the first victims. … Digging into government archives, Coudray uncovers shameful practices in a processed-meat sector unhinged by voracious industrial appetites.’

L’Humanité

ii

iii

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Guillaume Coudray is a French director and producer of documentary films. A political scientist by training, he is a graduate of Sciences Po and a former research grantee at the National Foundation for Political Science. His decade-long investigation into meat-processing has led to widespread press coverage and a hard-hitting documentary film broadcast in more than fifteen countries, which has had a major impact on the meat-processing industry. He lives in Paris.

Follow him on twitter at @g_coudray

ABOUT THE TRANSLATOR

David Watson is a freelance translator and editor. He has translated over 30 fiction and non-fiction books from French, including works by Alina Reyes, Agota Kristof, André Gide and a number of titles in the recent reissue of the Inspector Maigret novels by Georges Simenon. He lives in London.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

In Victorian England, pickled cucumbers were dyed green with copper-based dyes. Buyers preferred pickles with a lovely fresh green colour and sellers knew that by using plenty of dye, they could make a decent profit. What few people realised was that the green copper dyes were extremely poisonous.

Anyone today can see that it would be crazy to add green copper dye to pickles, no matter how appealing they may look. So why are we so uncritical of the countless bright pink meats in our supermarkets that have been processed using chemicals that increase their carcinogenic properties? As Guillaume Coudray reveals in this eye-opening and important exposé, our willingness to forgive bacon, ham and hot dogs for their cancer-causing properties has been carefully promoted by meat industry stakeholders who have spun us decades of lies.

I first read this book in French nearly three years ago. Even though my French is shaky, I couldn’t put it down. It read like a detective story unravelling a conspiracy against the eaters of the world.

Like anyone who reads the newspapers, I had long been aware of dramatic headlines linking the consumption of processed meats and colon cancer. Like anyone who enjoys an occasional bacon sandwich, I often pretended those headlines did not exist. It was only when I read Coudray’s devastatingly clear and far-reaching reportage that I understood how systematically the harm caused by ‘nitro-meats’ has been covered up by industry.

This is a book full of righteous anger. Coudray makes you feel how deeply wrong it is that the processed meat industry chooses to cure its meats with nitrate and nitrite even though it is well xivestablished that these chemicals give rise to cancer-causing compounds. What we are talking about here is preventable human suffering and death – all for the sake of achieving a rosy-red colour and speeding up production.

But this is also a book that offers reassurance to lovers of cured meats. The chink of light is Coudray’s revelation that thanks to alternative techniques, ‘the meat companies could produce perfectly safe processed meats without any need for harmful additives’. As of 1993, Prosciutto di Parma has been produced without any nitrate or nitrite, since when there has not been a single case of botulism associated with consuming the ham – contrary to all the warnings issued by the nitro-meat industry. The question is what it will take for other producers to follow suit.

As Coudray writes, when saltpetre (aka potassium nitrate) was first used in the curing of hams, there was no scandal, because the ham-makers did not know any better, just like those poor Victorians who poisoned themselves with green pickles. But now that we know better, to quote Maya Angelou, we should do better.

Bee Wilson

A NOTE ON TERMINOLOGY: SALT, NITRATE, NITRITE AND ‘NITRITED CURING SALT’

Salt

Historically, meat was cured using common salt. This is the white substance we all know and call simply ‘salt’, ‘sea salt’ or ‘cooking salt’. Its chemical name is sodium chloride. Even today, many types of processed meat are made using simple salting and maturation.

Nitrate

To speed up production and obtain a more uniform red colour, the salt can be supplemented by a derivative of nitrogen called nitrate. Nitrate comes in a variety of forms (ammonium nitrate, strontium nitrate, magnesium nitrate …), all of which give similar results in meat. The most commonly used is nitrate of potash or potassium nitrate. Historically, this was known as saltpetre.* Its E-number is E 252. Sometimes sodium nitrate (E 251) is also used.

Nitrite

Another derivative of nitrogen gives the same results as nitrate, but even more rapidly: nitrite. Many variants work well (ammonium nitrite, strontium nitrite, magnesium nitrite …). Nitrite can also be derived synthetically from nitrogen contained in the air or in vegetables. The cheapest is the most widely used: nitrite of soda or sodium nitrite. Its E-number is E 250.

‘Nitrited curing salt’

Sodium nitrite is so powerful it only requires a gram of powder to colour several kilograms of meat. In meat-processing it is never used in a pure state but only ever mixed with common salt. This mixture is known as nitrited salt, nitrite curing salt or nitrited curing salt. In Europe, nitrited curing salt contains between 99.1% and 99.5% common salt and between 0.5% and 0.9% nitrite. In the USA, nitrited curing salt is dosed at 6% and must be remixed with salt before use.

xvi

*Saltpeter in US spelling. This and other American spellings are retained when quoting US sources in this book. Similarly, the plural use of ‘nitrates’/‘nitrites’ is retained where appropriate in quoted material. Otherwise these terms are given in the singular.

PROLOGUE

It is 12 October 2015. One by one, the delegates walk into the small auditorium. Twenty-two researchers from all over the world. A number of observers file in around them and take up positions at the tables by the windows. We are in Lyon, at the home of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Founded by Charles de Gaulle, this agency is one of the jewels in the crown of the World Health Organization (WHO). Unlike other bodies in the cancer field, the IARC has virtually no involvement in drug development. De Gaulle wanted this organization to focus on one particular aim: to uncover the causes of cancer. Back in 1963, this was described as a ‘new approach’:1 it was no longer enough to seek a cure for cancer, its root causes also had to be identified.

Since its creation, the IARC has held large scientific conferences two to four times a year, and each one examines a specific group of substances. The sessions always follow a tried-and-tested procedure. In the preceding six months, the experts review all the known scientific results, eliminating those that are least relevant, in order to distil the essential results from thousands of documents. The meeting in Lyon is the final sprint. In the course of one week, the experts have to thrash out the issues and reach a conclusion. At the end of the deliberations a voluminous report – a monograph, in the jargon of the IARC – is produced, but everything boils down to those few lines of text that deliver the final decision, rather like a judge giving a verdict at the end of a long trial.

On this day in October 2015, the IARC experts decided to classify all processed meats in ‘group 1: carcinogenic to humans’.2 ‘Processed meats’ includes all products made of ‘meat preserved by smoking, curing or salting, or addition of chemical preservatives’,32in particular, bacon and gammon, salami, ham, smoked sausages, and corned beef. This was the first time the WHO had officially designated a whole type of foodstuff as ‘carcinogenic’.4 Two weeks later, when the new classification was released to the public, it made headlines everywhere. A large ‘X’ made of bacon appeared on the cover of Time magazine, which informed its readers that the global figure for deaths attributable to the consumption of processed meat had been estimated at 34,000.5 On its front page, the Financial Times criticized this ‘ham hysteria’ and advised its readers not to believe this ‘scaremongering’6 but rather to continue to ‘savour the bacon’.7 In Germany, Die Welt announced: ‘WHO places sausages on the cancer list’,8 and Die Tageszeitung suggested a ‘Salami tactic: to enjoy better health, use sparingly’.9 In France, Le Figaro and Le Parisien proclaimed: ‘Charcuterie is carcinogenic’.10The Times announced on its front page: ‘Processed meats blamed for thousands of cancer deaths a year’.11

The main form of cancer at stake here is colorectal cancer. It is one of the most frequent and deadliest of cancers: in the UK, it is the second most common cause of cancer death. Between 110 and 115 people receive a diagnosis every day – 42,000 new cases a year. More than half of patients survive, often after surgical removal of the tumours. But 43% of patients die. The figures for Europe are 500,000 new cases per year, with 238,000 deaths.12 On a global level, there are 1.8 million new cases each year and 861,000 deaths.13 Every five years, colorectal cancer affects 9 million people and kills approximately 4.3 million.14

Even though it is the second most deadly cancer in the world,15 it is one of the least well known among the general public. Is that because, on top of the taboo about cancer, people have an instinctive repulsion when it comes to faecal matter? For colorectal cancer is quite simply cancer of the large bowel: the colon is the tube that leads out of the small intestine. It is where the final 3acts of digestion take place (recuperation of water and vitamins, compacting of waste, storage prior to excretion). The rectum is the bottom end of the digestive tract: its last fifteen centimetres.

THE INDUSTRY MOBILIZES

The ‘group 1 carcinogen’ classification marks a turning point in the history of meat products. By using data assembled in the 1990s, the IARC indicated that a 50g portion of processed meat consumed every day increases the risk of colorectal cancer by 18%.16 Studies based specifically on recent British data have produced even more alarming figures: in spring 2019, researchers at the IARC and the Cancer Epidemiology Unit at Oxford University showed that a daily 50g portion of processed meat leads to a 42% increase in the risk of colorectal cancer.17 A daily 25g portion leads to an increase of 19%.18 A 25g helping is not a lot of processed meat: a rasher of cooked bacon weighs between 8g and 15g. A slice of ham weighs 10g for the smaller ones, 40g for the larger ones. A frankfurter-style sausage generally weighs around 40g, a slice of salami 10g, a gammon steak between 100g and 180g. As well as these there are the ‘hidden’ processed meats: slices of pepperoni on pizzas, the fillings in pork pies, pieces of ham in salads or ready meals … they all need to be factored in.19

The IARC’s assessment immediately had an impact on sales. One month after the release of the results, the Guardian headline read: ‘UK shoppers give pork the chop after processed meats linked to cancer’.20 But the European processed meat industry fought back, mobilizing its PR companies to conduct a damage-limitation exercise. In an interview with the Spanish daily El Pais entitled ‘The public has a choice: believe us or believe the industry’,21 Doctor Kurt Straif, who led the programme at the IARC, was scathing about these PR campaigns run by powerful industrial interests exercised purely by the impact on their bottom line.4

The meat companies churned out press statements full of mock surprise or incredulity; the scientific data were skilfully reviewed and ‘reframed’:22 the aim was to reassure consumers, convince them that there was really nothing to worry about, that the population was not exposed to any serious risk. Some industry voices portrayed the IARC as ‘just a lab’ and diminished its findings as just one study among many. They made out that the mechanisms that cause cancer are virtually unknown, or that the results indicated that processed meats represented only a ‘theoretical danger’, unrelated to any ‘real risk’. In each and every country, they explained that the IARC conclusions did not apply to local habits, that the consumers studied by the IARC were ‘statistical entities’, theoretical figments.

In fact, behind the figures there are real victims. In 2017, in the British Medical Bulletin, a researcher at the Institute of Food Research in Norwich calculated that the levels of risk published by the IARC meant that, ‘for every 100 male regular processed meat consumers we might expect approximately one additional case of colorectal cancer’23 (the levels were slightly lower in women). One case in every 100 consumers: the defenders of processed meat might argue that that is not such a big deal. But at the scale of a city, one male consumer in a hundred amounts to a very big deal. At the national scale, it is huge. As the British Medical Bulletin explains: ‘At the population level, differences in risk of this magnitude are of considerable significance for public health.’24 The epidemiologists estimate that of the 110 to 115 new cases of colorectal cancer that appear on average each day in the UK, about ten are directly related to the consumption of processed meats. Similarly, in the USA, it is estimated that 10.3% of cases of cancer of the colon are the direct result of the consumption of processed meat.25 (By way of comparison: in the same population, 13.5% of cancers of the colon are caused by cigarette smoking and 17% by alcohol.26) The carcinogenic impact of processed meats is understood in such precise detail that public health specialists have been 5able to show that in the United States a simple 6g reduction in the daily intake of processed meats would lead to a saving over ten years of a billion dollars on the cost of healthcare.27

OLD NEWS

In each of the producing countries, the processed meat industries have one powerful ally: the agricultural administrations are terrified by the economic consequences that a long-term collapse in sales would entail. The day after the IARC published its results, the French minister of agriculture declared: ‘I don’t want a report like this creating even more panic among people.’28 His concern was justifiable: in France, more than 70% of pork is consumed in the form of charcuterie. The implications of a drastic fall in sales are scary: 58% of French pork production takes place in a single region, Brittany, where the industry employs 30,000 people. The picture is no rosier in Germany, and that is the reason why the minister of agriculture in Berlin took the IARC to task over its results.29 Similarly, the Italian minister of agriculture attacked the cancer specialists and their ‘unjustified scaremongering’,30 and the Australian minister of agriculture used the word ‘farce’. In a radio interview he proclaimed: ‘If you got everything that the World Health Organization said was carcinogenic and took it out of your daily requirements, well you are kind of heading back to a cave.’31

Though it seemed to take some by surprise, the IARC’s classification was in fact the culmination of a long series of results proving the carcinogenicity of processed meats. At the end of the 1960s, the line of specialists working on bowel cancer was still: ‘the presence of carcinogenic factors swallowed and present in high concentration in the stool has been postulated but no such carcinogen has been identified’.32 By the 1970s they had gathered enough evidence to be able to accuse processed meats of being responsible for a considerable number of cancers – even if they 6couldn’t yet produce actual figures. Later we will describe how the health authorities had to take on the processed meat industry during that decade. Since then, epidemiological research has never stopped. In the 1990s, a large collection of biological samples was established together with data on individual behaviours (smoking and drinking, physical activity, eating habits): known as the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), the project concentrated on cancer and food-related factors analysed over a long period.

EPIC by name, epic by nature: the study covered half a million people and was based on 8 million samples taken at 23 collection centres across Europe. At the beginning of the study, there wasn’t a single case of cancer. As the years went by, cancers began to appear. A retrospective analysis of the accumulated data allowed precise links to be established between certain behaviours and the occurrence of certain cancers. The epidemiologists who headed up EPIC obtained definitive proof of the role of processed meat in cancer induction. From 2002, they provided preliminary figures suggesting that eating 30g of processed meat every day was likely to increase risk of cancer by 36%.33 In 2003, the WHO published a preliminary recommendation aimed at limiting the quantities of processed meat consumed.34 But the real turning point was the publication of two reports, in 1997 and then in 2007, by the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF): having conducted an analysis involving a team of the best cancer specialists and epidemiologists, the WCRF concluded its evaluation with the recommendation: ‘avoid processed meat’.35 In 2012, the American Cancer Society recommended that people should ‘minimize consumption of processed meats such as bacon, sausage, luncheon meats, and hot dogs’.36 Meanwhile in Europe, summing up the state of scientific knowledge on the prevention of colorectal cancer, the Belgian Superior Health Council recommended ‘avoiding as much as possible processed red meat’37 and only consuming such products ‘rarely, if at all’.387

NITRO-MEATS

In fact, it is not necessary to give up eating processed meats to reduce the risk of cancer. What needs to be reduced – eliminated altogether if possible – is carcinogenic processed meat. This truism contains a secret that the processed meat industry tries hard to obscure in its many communications on the subject: when it comes to cancer, not all processed meats are equal. Some are very dangerous, others less so, while others still have been shown in laboratory tests to have no harmful effects.39

Processed meats are made especially dangerous by the use of two food additives: nitrite and nitrate, which accelerate the curing process and give the meat an appetizing colour. Nitrate and nitrite are chemical substances composed of a nitrogen atom bound to three (for nitrate) or two (for nitrite) oxygen atoms. Nitrate is abundant in the natural world: some vegetables (such as spinach, beets, lettuce) contain a high concentration of nitrate, which may be transformed into nitrite by the action of micro-organisms. This transformation (the chemical term is reduction) occurs in the oral cavity; that is why saliva contains low concentrations of nitrite that is continually swallowed in a highly diluted solution.40

Nitrate and nitrite are not carcinogenic in themselves. But under certain conditions they can be transformed. Then they give rise to free radicals, in particular nitric oxide (NO). Highly reactive, and known for its role as an electron-thief or oxidizer, this oxide of nitrogen reacts with a wide range of biological molecules (lipids, proteins, DNA). When the nitric oxide reacts with the components of meat – especially with iron and with amides or amines derived from meat proteins – it leads to the production of certain carcinogenic compounds that the chemists call nitroso compounds or N-nitroso compounds (scientists use the terms interchangeably, some preferring the abbreviation ‘NOCs’ for ‘nitric-oxide-releasing compounds’).41 These molecules result from 8the interaction between nitrite and elements in the meat itself; that is why these nitroso compounds are said to be ‘neo-formed’. They damage the cells lining the bowel.42 It is a long process, which typically takes ten to fifteen years: over time, the slow accumulation of damage leads to the proliferation of cancerous cells.43

In 2015, the French cancer specialist Denis Corpet was the chairman of the group of experts commissioned by the IARC to evaluate the mechanisms that lead to the appearance of tumours. Four years later, in early 2019, Professor Corpet expressed his indignation: ‘The failure of governments globally to engage on this public health scandal is nothing less than a dereliction of duty – both in regards to the number of cases that could be avoided by ridding nitrites from processed meats – and in the potential to reduce the strain on increasingly stretched and under-funded public health services.’44 In a letter addressed to the European commissioner for health, he reiterated that nitro-additives, by reacting with meat, give birth to carcinogenic nitroso compounds. ‘The research team I led at the university of Toulouse demonstrated that while an experimental nitrite-cured ham promotes colorectal carcinogenesis in rats, the same ham cured without nitrite does not’,45 he explained. When the lab rats were fed with two separate batches of ham (one made by using nitrite, the other without it), only the nitro version led to the development of tumours.46 Corpet concluded his letter to the European authorities by saying: ‘The addition of nitrites to foods such as ham and bacon is thus central to cancer risk – and marks out those meats that contain these chemicals as significantly more dangerous than other processed meats.’47

ALL IN A GOOD CAUSE: THE BOTULISM ARGUMENT

On the occasions when the industrial meat-processors implicitly recognize that their nitrited meat is carcinogenic, they claim it is 9all in a good cause. According to them, nitro-additives are there to protect consumers from an even greater danger than cancer: they insist that nitrate and nitrite are needed to prevent botulism, a dangerous illness caused by a bacterium. They allege that the use of nitrate and nitrite is the only safe way to destroy germs that might be lurking in sausages and ham, waiting to kill those unwise enough to eat meat that hasn’t been ‘treated’. The CEO of a large French industrial meat-processor gave this explanation of why he refused to stop using sodium nitrite in ham and frankfurters: ‘We don’t stick it in out of habit or just for the fun of it. We put it in to combat a very grave evil: botulism, which is fatal … This isn’t a bout of indigestion we’re talking about. With botulism we’re talking death! … With botulism, it’s game over!’48

So it’s a cost–benefit calculation, a case of the lesser of two evils: like a responsible parent, the meat-processing industry would rather risk giving cancer to a minority of consumers in order to protect the others. It’s hard to find an equivalent elsewhere: would it be acceptable if orange juice killed thousands of people each year to protect everyone else from some mysterious ‘orange poison’? Would parents feed their children chips if the flesh of the potatoes had been rendered carcinogenic by the introduction of some additive? Would the risk of bird flu be enough to induce consumers to eat chicken injected with a carcinogenic solution?

But the worst thing about this is that the botulism argument is factitious. In fact, manufacturers have a whole arsenal of techniques to prevent bacterial infections. ‘We conclude that any effect of nitrite on product safety and stability may be compensated for by modification of formulations and processes’,49 explained the German biologist Friedrich-Karl Lücke, a specialist in processed meats, in 2007. For decades, in article after article, the experts in meat microbiology have been echoing this: simply by using adapted production techniques, the meat companies could produce perfectly safe processed meats without any need for harmful 10additives.50 And those who like their ham pink can rest assured: there are alternative colouring methods. Back in 2008, in response to the report of the World Cancer Research Fund, three of the most respected European meat scientists wrote: ‘It is now known that acceptable alternatives for the use of nitrate and nitrite exist in relation to color development, flavor and microbiological safety.’51 Ten years later, chemists and biochemists were still making the same point: ‘the use of nitrate and nitrite may be substituted by modifications of product composition, and processes’.52

From artisan pork butchers to small family enterprises to sizable factories producing hundreds of thousands of tons of meat a year, manufacturers large and small throughout Europe are working perfectly well without using nitrate and nitrite and yet have never recorded a single case of the ‘inevitable’ botulism that the nitro companies wield as their weapon of fear. To do without carcinogenic additives, they use different methods: they buy raw meat of better quality, they apply stricter rules of hygiene, they use longer periods of refrigeration and maturation, they adapt their equipment to meet these requirements. In the UK and Denmark a handful of industrial manufacturers make bacon and ham without using nitro-additives. In Germany and Holland organic producers likewise eschew all additives. In Italy the best products (Parma and San Daniele dried hams) are made without nitrate and nitrite. Similarly in Spain the top-notch meat products (authentic chorizo and lomo, most authentic bellota hams) are not treated with nitro-additives. In France and Belgium, artisan and industrial meat-processors are vying to bring nitrate- and nitrite-free products to the market. Some of them cater for purely regional markets, others already distribute on a national scale, such as the Biocoop group, which, in autumn 2017, launched an excellent ham without nitro-additives that is made in Brittany. It is a ham that doesn’t cheat: it has its own true colour. The distributor is quite happy to make the case for it on its packaging: ‘Pale ham, 11is that normal? Yes, if you don’t add nitrited curing salt the ham retains its natural colour, that is, grey!’53

This proves that the sector can change, that ‘virtuous’ processed meats can be successful. But most of the market leaders baulk at the prospect: processing meat without using nitro-additives takes more time and requires more care. Adapting equipment does not come cheap: machines need to be changed, refrigeration units revamped, production processes revised – a complete overhaul. Why undertake such expense only to end up with a product that is less pink and thus likely to sell less?

IT’S ENDEMIC

Listening to the industry spokespeople, you would think that they have been straining every sinew over the last few decades to minimize the use of additives that make processed meats carcinogenic.54 In fact, the number of nitro-treated products is growing relentlessly. It is the strange paradox of carcinogenic meats: the more it has been understood how dangerous they are, the more they have grown in numbers. Thus nowadays, in the UK, the ‘farmhouse pâté’, ‘Brussels pâté’ and ‘Ardennes pâté’ sold in supermarkets is often treated with sodium nitrite. The chemical produces an appetizing pink colour which makes for an appealing aspect when sold sliced and wrapped in transparent packaging. And yet in France and Belgium (for example in the Ardennes) the pâté is often not treated: it isn’t pink, but grey. Another example: rillettes (potted meat), a traditional product of rural western France. The technical guides make clear that it is not necessary to use preservatives in rillettes, as the cooking pasteurizes them.55 That is why the first Code of Practice for Charcuterie, published in 1969, explicitly forbade the use of nitro-additives in rillettes: only salt and spices were allowed.56 Even though aware of the cancer risk, the professional organizations gave the nod to nitrite curing in rillettes. A 12reference manual says: ‘This technique is not of particular interest unless you are seeking to bring pinkness to meat pieces in the final product.’57 For many years now, the number of carcinogenic rillettes being sold in shops has increased, especially in cut-price and discount stores. So the injustice deepens: as with ham and sausages, it is always the cheapest products – that is, those consumed by households on modest means – which are treated the most with nitro-additives.

By way of an excuse for not banning these dangerous additives, the European Commission explains that it has not taken any measures because of ‘the need for certain traditional foods to be maintained on the market’.58 But in fact this liberal attitude essentially benefits products that are far from ‘traditional’: since nitrite curing is allowed, European industrial meat-processors have consistently come up with new products which rely on the use of this miracle additive. Instead of favouring healthier options, the manufacturers are permanently competing to develop new formulae and new nitro-meats. You simply have to peruse the supermarket shelves to clock the appearance of new items with labels that list E 250 (sodium nitrite), E 251 (sodium nitrate) and E 252 (potassium nitrate). All tastes and all ages are catered for: nitro treatment is used even in products aimed specifically at children and teenagers. And in this incessant escalation, there is one constant theme: nitro treatment lowers costs, accelerates production, simplifies the work of factories, prolongs shelf life and is the quickest way to achieve that lovely colour that customers like so much.

As for cancer, the organizations that represent the industry point out that they fund research. And the result of this work? Researchers confirm that the simplest solution would be to ban nitro-additives altogether. But as far as the industry is concerned, that is out of the question: there’s too much to lose. So the biochemists suggest adding supplementary chemicals to counteract the carcinogenic action (especially tocopherol, a compound which has 13powerful antioxidant properties).59 For years, nitro-meat manufacturers have been floating this idea: they claim that if we wait just a bit longer, a new revolutionary method will be developed that will allow the risk to be nullified, and this will suit everyone: for the public, fewer deaths; for the industry, no change to the look of the product and no costly adaptation of processing technology.

But if you delve into the history of the link between cancer and processed meats, you discover that studies into such inhibiting techniques were being announced as long ago as the 1970s, when the industry was first confronted with evidence of the carcinogenicity of nitro-meats.60 Early formulae of anti-cancer tocopherol were already developed and patented in the late 1970s.61 So how do we explain that the processed meat industry is still at this preliminary stage of development? Whom does this inertia benefit the most? How can we tolerate the fact that hundreds or thousands of deaths have been caused by this procrastination? Why trust the industry lobby when we learn that their current statements are almost verbatim repetitions of what was said back in 1975: ‘To date, no substitute for nitrite has been discovered’;62 or else ‘Researchers are still trying to find a replacement’?63 Already in the 1970s, cancer specialists were critical of these dilatory tactics.64

As the manufacturers buy themselves more time, consumers are being poisoned. Systematic nitrite curing hurts everyone: consumers, who are made ill; health services, which have to expend valuable resources in expensive treatments; pig farmers, who are impoverished by allowing the processors to use meat of mediocre quality. And the meat curers themselves: when they make sincere efforts to produce healthier food, they are discouraged by having to compete against nitro products, with their perfect pink colour and their unbeatable prices – because they are produced quickly and with less care. The only winners are a few giant industrial companies who, thanks to nitrite, can rapidly produce meats that look as tasty as sweets and stay that way for a long time.14

DON’T BRING HOME THE BACON

Rather than force the meat industry to give up nitrite curing, most countries prefer what might be termed ‘the diagnostic and therapeutic option’. People over 50 are encouraged to provide stool samples and, if necessary, undergo a colonoscopy. When pre-cancerous cells are detected, the patients are operated on. Promotional campaigns riff on the theme of: ‘90% of colorectal cancers are treatable when detected early.’ This is all very comforting, but contrarians might point instead to a crueller statistic: even in countries with an advanced hospital system, four out of ten people diagnosed with bowel cancer don’t survive five years after diagnosis.65 And beyond the statistics, each of these ‘cases’ represents enormous hardship for individuals and their families. Sometimes, the surgeon removes a piece of intestine and diverts one end of the colon through an opening in the belly. Who can hope to lead a normal life with a plastic colostomy bag attached to their abdomen to collect their bodily waste?

Rather than a genuine strategy based on tackling the causes of cancer, this combination of screening and treatment of patients already affected by cancer is passed off as ‘prevention’. And too bad if the less well-off in society, who happen to be the largest consumers of processed meat, bear the brunt (in the UK, recent studies have shown that those in the most deprived social categories are disproportionately more prone to cancer than the rest of the population).66

And what does it matter if, following the USA and Europe, the number of cases of colorectal cancer is increasing in the Global South as they begin to adopt Western eating habits? As early as 1971, the British surgeon and epidemiologist Denis Burkitt, a pioneer in the identification of the role of food in colorectal cancer, was pointing out: ‘The rise in bronchial carcinoma accompanied an increase in cigarette smoking, and likewise the rise in colon 15carcinoma accompanied a progressive adaptation to a North American type of diet.’67 He noted, for example: ‘Rural Africans rarely develop cancer of the large bowel, but when these same people move into a city and start eating Western-style food, their susceptibility to this type of malignancy increases dramatically and eventually matches the high rates found in Europeans and Americans.’68 The same goes for Asian populations: ‘The Japanese, especially in rural areas, also have very few malignancies of the colon. But when they migrate to Hawaii or California, their children have almost as many bowel cancers as the general population of these areas.’69 According to the historian Robert Proctor, Denis Burkitt was one of the first to denounce the lack of any nutritional prevention policy for cancer: Burkitt ‘suggests that we have a leaky faucet, an overflowing sink, and many experts busily mopping the floor. But why, he says, are there so few trying to turn off the tap?’70

The artisan producers who use nitro-additives often do so with regret: they would prefer to sell food that isn’t detrimental to health. I hope that this book, by introducing them to the secret history of nitrate and nitrite, will offer them encouragement: they will discover how traditional meat curing was taken over by industrial groups obsessed with speed and volume, often indifferent to the health of their customers and willing to employ any ruse so as not to have to give up their recipes for ‘accelerated meat curing’. These nitro-meats look lovely, but they are dangerous. It is time for real meat curers to take back control of their salt.16

293Notes

1 Roger Sohier and A.G.B. Sutherland, The Origin of the International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC technical report no. 6, IARC, Lyon, 2015.

2 Véronique Bouvard et al., ‘Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat’, The Lancet Oncology, 16, 16, December 2015.

3 World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research, Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective, WCRF-AICR, Washington, 2007, p. 382. The IARC gives the following definition: ‘Processed meat refers to meat that has been transformed through salting, curing, fermentation, smoking or other processes to enhance flavour or improve preservation.’ (Bouvard et al., ‘Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat’, art. cit.)

4 Apart from alcohol, and before processed meats were classified as ‘carcinogenic to humans’, there was only a single food product classified in group 1: Chinese-style salted fish, a cause of cancer of the nasopharynx. See IARC, ‘List of classifications by cancer sites with sufficient or limited evidence in humans, volumes 1 to 124’, IARC, October 2019.

5 Mandy Oaklander and Heather Jones, ‘The science behind how bacon causes cancer’, Time, 26 October 2015.

6Financial Times, 28 October 2015, p. 1.

7 Tim Hayward, ‘You can either savour the bacon or relish the hysteria’, Financial Times, 28 October 2015, p. 9.

8 ‘WHO setzt Wurst auf die Krebsliste’ [WHO puts sausage on the cancer list], Die Welt, 27 October 2015, p. 1.

9Taz die Tageszeitung, 27 October 2015, p. 1.

10 ‘La charcuterie est cancérogène, la viande rouge “probablement” aussi selon l’OMS’ [Charcuterie is carcinogenic, and ‘probably’ red meat too, according to the WHO’, Le Figaro, 26 October 2015; ‘OMS: la charcuterie cancérogène, la viande rouge aussi “probablement”’, Le Parisien, 26 October 2015.

11 Chris Smyth, ‘Processed meats blamed for thousands of cancer deaths a year’, The Times, 27 October 2015, p. 1.

12 IARC/WHO, ‘Population fact sheet: Europe’, May 2019, available at gco. iarc.fr.

13 IARC/WHO, ‘Population fact sheet: World’, May 2019, available at gco. iarc.fr.294

14 Freddie Bray et al., ‘Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries’, CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68, 6, September 2018.

15 Ibid.

16 IARC, press release no. 240, ‘IARC monographs evaluate consumption of red meat and processed meat’, 26 October 2015.

17 Kathryn Bradbury et al., ‘Diet and colorectal cancer in UK Biobank: a prospective study’, International Journal of Epidemiology, April 2019. According to this study, each 25g/day increment in processed meat intake is associated with a 19% increase of colorectal cancer. The risk being on a log scale, each 50g/day increment in processed meat intake is associated with a 42% higher risk. Each 75g/day increment in processed meat intake is associated with a 69% higher risk.

18 Ibid.

19 The French National Cancer Institute says: ‘The category of processed meats includes all meats preserved by smoking, drying, salting or addition of preservatives (including mince, if it is chemically preserved, corned beef …) […] They include those that are eaten on their own (including ham) and those included in other dishes, sandwiches, savoury tarts …’ (Institut national du cancer, Nutrition et prévention des cancers: des connaissances scientifiques aux recommandations [Nutrition and Prevention of Cancers: From Scientific Knowledge to Recommendations], INCa, Paris, 2009, pp. 24–5.)

20 Aisha Gani, ‘UK shoppers give pork the chop after processed meats linked to cancer’, The Guardian, 23 November 2015.

21 Kurt Straif quoted in Nuño Dominguez, ‘Que el público decida en quién confiar, la industria o nosotros’ [The public has a choice: believe us or believe the industry], El Pais, 28 October 2015, p. 27.

22 For example, see this statement (November 2016) on the website set up by French meat-processing companies (www.info-nitrites.fr): ‘Cancer is an illness involving multiple factors both food-related and non-food-related, and the essentially international research by the IARC does not take account of specific local factors (nature of the products, actual consumption …) […] Another important point to be taken into account: data are relevant only to populations consuming over 50g of processed meat a day. In France the daily consumption of processed meat is around 36g per day.’ This statement is false: on the contrary, the IARC experts were clear that they were not suggesting a dose below which the consumption of processed meat involved no risk of cancer. The benchmark 50g is not the point where risk comes into play but is a threshold of more elevated risk.

23 Ian Johnson, ‘The cancer risk related to meat and meat products’, British Medical Bulletin, 121, 1, January 2017.

24 Ibid.

25 Farhad Islami et al., ‘Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States’, CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68, 1, January–February 2018, p. 39.295

26 Ibid., pp. 38–9.

27 David Kim et al., ‘Cost effectiveness of nutrition policies on processed meat: implications for cancer burden in the U.S.’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57, 5, November 2019, p. 6.

28 ‘Viande/cancer: Le Foll met en garde contre la “panique”’ [Meat/cancer: Le Foll warns against ‘panic’], europe1.fr, 26 October 2015.

29Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 28 October 2015, p. 17.

30 ‘Carni lavorate e cancro, Lorenzin: da OMS allarmismo ingiustificato’ [Processed meats and cancer, Lorenzin: unjustified scaremongering from the WHO], Corriere della sera, 29 October 2015.

31Sydney Morning Herald, 27 October 2015.

32 Hugh Lockhart-Mummery, ‘Cancer of the rectum’, in Basil Morson (ed.) Diseases of the Colon, Rectum and Anus, William Heinemann Medical Books Ltd, London, 1969.

33 Teresa Norat et al., ‘Meat consumption and colorectal cancer risk: dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies’, International Journal of Cancer, 98, 2002.

34 Joint WHO/FAO expert consultation, Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Disease, OMS, Geneva, 2003, p. 101.

35 Recommendation no. 5 in World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research, Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective, op. cit., p. 382.

36 Lawrence Kushi et al., ‘American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention’, CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 62, 1, 2012, p. 39.

37 Conseil supérieur de la santé, ‘Viande rouge, charcuterie à base de viande rouge et prévention du cancer colorectal’ [Red meat, red processed meat and prevention of colorectal cancer], Brève (Notice no. 8858), Brussels, 2013, p. 2.

38 Ibid.

39 Denis Corpet, ‘Red meat and colon cancer: Should we become vegetarians, or can we make meat safer?’, Meat Science, 89, 2011.

40 Susan Preston-Martin et al., ‘Maternal consumption of cured meats and vitamins in relation to pediatric brain tumors’, Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 5, 1999, p. 600.

41 William Lijinsky, ‘N-Nitroso compounds in the diet’, Mutation Research, 443, 1–2, 1999.

42 Nadia Bastide et al., ‘A central role for heme iron in colon carcinogenesis associated with red meat intake’, Cancer Research, 75, 5, March 2015; Diane de La Pomélie et al., ‘Mechanisms and kinetics of heme iron nitrosylation in an in vitro gastro-intestinal model’, Food Chemistry, 239, January 2018.

43 William Grady, ‘Molecular biology of colon cancer’, in Leonard Saltz (ed.), Colorectal Cancer: Evidence-Based Chemotherapy Strategies, Humana Press, Totowa, 2007, p. 1.296

44 Denis Corpet, letter addressed to the EU commissioner for health and food safety and the UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, 7 February 2019.

45 Ibid.

46 Denis Corpet, ‘Red meat and colon cancer: Should we become vegetarians, or can we make meat safer?’, art. cit.; Raphaelle Santarelli et al., ‘Meat-processing and colon carcinogenesis: cooked, nitrite-treated, and oxidized high-heme cured meat promotes mucin-depleted foci in rats’, Cancer Prevention Research, no. 3, 2010.

47 Denis Corpet, letter addressed to the EU commissioner for health and food safety and the UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care (letter cited).

48 Interview with the CEO of Herta France in a film directed by Sandrine Rigaud, co-authored by Guillaume Coudray, Cash Investigation: ‘Industrie agroalimentaire: business contre santé’ [Agro-food industry: business versus health], France 2, September 2016 (available on www.youtube. com).

49 Friedrich-Karl Lücke, ‘Nitrit und die Haltbarkeit und Sicherheit erhitzter Fleischerzeugnisse’ [Nitrite and the shelf life and safety of heated meat products], Mitteilungsblatt der Fleischforschung Kulmbach [Kulmbach Bulletin of Meat Research], 47, 181, 2008.

50 See, for example, EFSA, ‘Opinion of the scientific panel on biological hazards on a request from the Commission related to the effects of nitrites/nitrates on the microbiological safety of meat products’, EFSA Journal, 14, 2003 (p. 24, ‘Germany’ and ‘Italy’); Food Chain Evaluation Consortium, Study on the Monitoring of the Implementation of Directive 2006/52/EC as Regards the Use of Nitrites by Industry in Different Categories of Meat Products, European Commission/Civic Consulting, Brussels, 2016, p. 6.

51 Daniel Demeyer et al., ‘The World Cancer Research Fund report 2007: a challenge for the meat-processing industry’, Meat Science, 80, 2008, p. 956.

52 Didier Majou and Souad Christieans, ‘Mechanisms of the bactericidal effects of nitrate and nitrite in cured meats’, Meat Science, 145, 2018.

53 Jambon Biocoop (Ensemble label), Bio direct/SBV viande, Le Petit Brevelay.

54 ‘Les nitrites au coeur des charcuteries’ [Nitrites at the heart of processed meats], Infos Viandes et Charcuteries [Meat and Processed Meat Info], November 2013, Ifip-Institut du porc, p. 1.

55 See, for example, ‘Rillettes du Mans, de Tours et rillons’ [Rillettes of Le Mans and Tours and rillons], in Louis-François Dronne, Charcuterie ancienne et moderne. Traité historique et pratique [Ancient and Modern Charcuterie: Historical and Practical Guide], E. Lacroix, Paris, 1869, pp. 177–8 or ‘Rillons’ and ‘Rillettes’, in Marc Berthoud, Charcuterie pratique [Practical Charcuterie], Hetzel, Paris, 1884, pp. 201–02.

56 Centre technique de la salaison, de la charcuterie et des conserves de viandes [Technical Centre for Cured, Processed and Preserved Meats], 297Code des usages en charcuterie et conserves de viandes [Code of Practice for Charcuterie and Preserved Meats], Paris, 1969, section V, p. 29.

57 Jean-Claude Frentz and Michel Poulain, Livre du compagnon charcutiertraiteur [Pork Butcher and Delicatessen Companion Book], Éditions LT Jacques Lanore/Jérôme Vilette, Les Lilas, 2001, p. 260 (our emphasis).

58 Answer E-3840/2010 (23 June 2010); Commission Regulation No. 1129/2011 of 11 November 2011, Official Journal of the European Union, L 295/1.

59 Fabrice Pierre et al., ‘Calcium and α-tocopherol suppress cured meat promotion of chemically-induced colon carcinogenesis in rats and reduce associated biomarkers in human volunteers’, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 98, 5, November 2013.

60 See, for example, the 10th reunion of the Expert Panel on Nitrites and Nitrosamines (March 1977), in Expert Panel on Nitrites and Nitrosamines, Final Report on Nitrites and Nitrosamines. Report to the Secretary of Agriculture, USDA, Washington, February 1978, pp. 78–9; also William Mergens et al., ‘Stability of tocopherol in bacon’, Food Technology, November 1978, pp. 40–4.

61 J. Ian Gray et al., ‘Inhibition of N-nitrosamines in bacon’, Food Technology, 6, 6, 1982; Walter Wilkens et al., ‘Alpha-tocopherol’, Meat Processing, September 1982; ‘Bacon breakthrough’, Meat Industry, September 1982.

62 ‘Nitrites and nitrosamines advisory panel challenged’, Congressional Record – Senate, 19 December 1975, p. 42089.

63 Ibid.

64 See, for example, Expert Panel on Nitrites and Nitrosamines, Final Report on Nitrites and Nitrosamines, op. cit., p. 14.

65 Cancer Research UK, ‘Bowel cancer statistics’ and ‘Bowel cancer survival statistics’, Cancer Research UK (data for England and Wales, 2010–2011).

66 See Raymond Oliphant et al., ‘The changing association between socioeconomic circumstances and the incidence of colorectal cancer: a population-based study’, British Journal of Cancer, 104, May 2011; Emily Tweed et al., ‘Socio-economic inequalities in the incidence of four common cancers: a population-based registry study’, Public Health, 154, January 2018.

67 Denis Burkitt, ‘Epidemiology of cancer of the colon and rectum’, Cancer, 28, 1, July 1971, pp. 5–6.

68 ‘Modern diet may play role in cancer of the bowel’, JAMA, 215, 5, 1 February 1971, p. 717.

69 Ibid.

70 Robert Proctor, Cancer Wars. How Politics Shapes What We Know and Don’t Know About Cancer, Basic Books, New York, 1995, p. 261.

PART 1

IN THE PINK: HOW YOUR BACON ENDED UP FULL OF NITRATE AND NITRITE18

CHAPTER 1

MIRACLE ADDITIVES

Even before we engage our sense of taste or smell, we use our eyes to select what we are going to eat. We react positively to the green colour of vegetables. The sight of a ripe apple or raspberry makes the mouth water, but if these fruits are painted blue we find them repulsive. As for meat, millions of years of evolution as carnivores have taught us to judge the freshness of flesh by its colour: our instincts interpret certain colours as offering guarantees against pathogens. ‘Red’ signifies quality; ‘pink’ expresses safety.

Unfortunately, the natural colour of ham and sausages is not pink: it is grey or brown, the same as pork after it has been cooked. Which is why meat curers have constantly been tempted to use artificial means to recreate the colour of fresh meat. The pink hue of hams/sausages/pâtés is the result of two products: potassium nitrate (chemical symbol KNO3) and ‘nitrited curing salt’, a mixture of cooking salt and sodium nitrite (NaNO2).

NITRATE, NITRITE AND IRON

As we saw earlier, nitrate and nitrite are not directly carcinogenic: even with repeated ingestion, nitrate and nitrite do not cause tumours in either animals or humans. But under certain conditions these substances can give rise to several carcinogenic agents. The best known are nitroso compounds, which can form during 20the processing, cooking or digestion of meat. Firstly, there are the nitrosamines, molecules formed by the combination of nitrosating agents (nitrite, nitrous acid, nitrogen oxides) and amines (amines form from the breakdown of amino acids, peptides and proteins). The other group of nitroso compounds contains nitrosamides, which form when a nitro agent reacts with an amide (an organic compound similar to amines). Nitrosamines and nitrosamides work even in low doses: they target the DNA of cells and cause lesions which can lead to tumours.

Industrial meat-processors claim that by adding vitamin C to their products they reduce the risk posed by nitroso compounds. This technical solution was invented in the 1950s and is in widespread use today: a great many nitro-processed meat products are supplemented with vitamin C (in the form of ascorbate) to speed up their production and to try to reduce the frequency of nitrosamines. Nevertheless, nitro-processed meat remains carcinogenic, as it contains other agents that generate tumours: those that result when nitro elements encounter iron contained in meat (specialists call it ‘haem iron’). When it is consumed in excess, the iron trace element has a pro-oxidant effect that stimulates cancerous cells. That is why the IARC, when it examined processed meat in October 2015, classed untreated red meat in category 2 (‘probably carcinogenic’). The carcinogenic effect of haem iron is activated when meat is treated with nitrate or nitrite, as the element iron reacts with nitric oxide to create nitrosyl haem, an agent that is key to carcinogenesis.1

For producers of nitro-processed meat, acknowledging this mechanism means, in a sense, accepting their own death warrant: whereas the nitrosamine risk manifests itself only under certain conditions in cooking and digestion, the nitrosyl haem risk is potentially latent in every particle of nitro-meat. The only solution is to stop using nitro-additives and return to traditional methods of curing meat, using only meat and common salt.21

THE NATURAL PIGMENT OF RAW HAM

Archaeologists have shown that humans have been salting pork in Europe at least since the Bronze Age (tenth century BCE), especially the Celts. In the area of modern-day France, excavations have uncovered several sites of salting workshops.2 For example, in his depiction of Gaul in 18 CE, the geographer Strabo writes: ‘These people produce magnificent cuts of salted pork that are exported as far as Rome itself.’3

In many regions of Europe, ham is still made following ancestral methods, that is, using only salt and no additives. This is the case for certain Spanish hams (most traditional bellota and pata negra), but it is mainly in Italy that the most famous examples of nitrate- and nitrite-free hams are to be found today. These meat products are created using the ancient procedures: after having been rubbed down with salt, the meat first of all takes on a brown tinge. Then, after a few weeks, without any other external intervention, a red colour starts to emerge, which becomes more and more intense. Humans have been exploiting this phenomenon for millennia, but it is only in the last twenty years that Italian and Japanese scientists have managed to work out the biochemical process involved: when an artisan makes a raw ham without nitrate or nitrite, he is unwittingly bringing a new pigment into being. Through the action of an enzyme present in the flesh, a part of the element iron contained in the meat is replaced with the element zinc. The scientists call this natural pigment of cured meat ‘zinc protoporphyrin’ (Zn-pp or ZPP).4

This pigment does not appear only in ham: in the past it was zinc protoporphyrin that gave dried beef that red colour that our ancestors called ‘brési’ or ‘brazi’; today it is zinc protoporphyrin that gives an intense colour to the traditional (nitrate- and nitrite-free) sausages that are still found in Auvergne, Corsica, Spain and especially in Italy and Hungary. But Zn-pp entails 22certain constraints. Choice of ingredients, precision of method, control of temperature, acidity, humidity: contemporary Italian salumerie demonstrate the care and attention required to produce an authentic salami. If not done well, the maturing process can end up with a poor-tasting product that doesn’t keep very long. Furthermore, this traditional method of production has another major disadvantage: it is slow. The zinc protoporphyrin pigment forms gradually throughout the whole period of production but grows most rapidly during the maturing process.5 It achieves a satisfactory colour only after several months and continues to improve with time, because the longer the maturing process is, the more the quantity of Zn-pp pigment increases. The taste improves at the same time as the colour: in Spain, true pata negra without nitrate or nitrite generally takes 24 months to reach the market. As with wine, traditional hams improve with age: in Auvergne, up until just a few decades ago, dried hams would be strung from the ceilings of houses of well-off peasants, maturing for years in anticipation of a wedding or some other major occasion.

SPEEDING THINGS UP

Almost everywhere, traditional methods of production have been replaced by an accelerated process. In France, the most striking example involves the famous ‘Bayonne ham’. Today, most Bayonne hams are treated with potassium nitrate (saltpetre), but traditionally they were produced using only salt, with neither nitrate nor nitrite.6 Until the end of the 1960s, the Fraud Prevention Office prohibited the use of the expression ‘real Bayonne ham’ if the producers made use of nitro-additives.7