2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Felicitas Hübner Verlag

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

Biologist and technical diver Dr. Klaus M. Stiefel explains some exciting new insights into the workings of the human brain for the interested layperson. Topics include novel results on the mechanism causing the dreaded which can distort a diver's senses and the brain-mechanisms of controlling breathing and breath hold during freediving (apnea diving). The book also discusses new scientific results about the genetic adaptation of Southeast Asia's "sea gypsies" (the Bajao tribe) to extended breath hold diving.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 66

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Imprint

Author: Klaus M. Stiefel

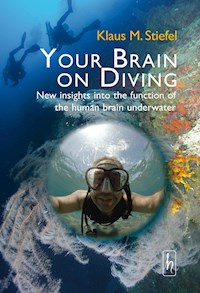

Title: Your Brain on Diving

Subtitle: New insights into the function of the human brain underwater

All rights reserved. Even the publication or reproduction of excerpts of any kind, apart from review citations, requires the permission of the publisher. This applies in particular to electronic or other reproduction, translation, distribution and making available to the public.

© 2022 by Felicitas Hübner Verlag GmbH (huebner-books), Apensen, Germany

Excerpts from the original German language edition “Gehirn extrem”, © 2019 by Felicitas Hübner Verlag GmbH (huebner-books), Apensen, Germany

Photos © by Klaus M. Stiefel

Cartoons “Synapsis” © by Anna Farell

Translation © by Klaus M. Stiefel

ISBN 978-3-941911-80-2

www.huebner-books.de

Table of Contents

Imprint

Diving and Brains: A Brief Intro

Inert Gas Narcosis

What Nitrogen Does to Brain Cells

Nitrogen-Altered Brain Waves

Whale Brains

Apnea

Breathing and the Brain

Oxygen Use

Fear and Loathing Underwater

The Hindbrain Again

Badjao Superpower

Human Free Diving Evolution

About the Author

Literature

Diving and Brains: A Brief Intro

I love to be underwater, to the point that I took up diving as a teenager and now spend time underwater almost every week, sometimes teaching scuba courses, and often filming and photographing the subaquatic world. I also have a burning desire to understand what goes on in our brains, so much that I took up neurobiology as the subject of my graduate studies in 1998 at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research. The passions for diving and for neurobiology seemed disjoint at first, even to myself, but in recent years I have seen a number of fascinating overlaps.

We humans are, of course, land mammals, and sticking our head underwater and exposing ourselves to increasing water pressure will have effects on our bodies, some of which we were equipped to deal with by Mother Evolution; others catch our bodies off guard. As so often, the most intense and curious effects show up in our bodies’ most complex organ, the brain. Anybody who has scuba dived to more than about 30 meters will attest to the mind-spinning effects of inert gas narcosis.

When Felicitas Hübner and I planned a popular science book on extreme brain states, it was clear to me that I wanted to make the effects of diving on human brains one of the topics of the book. “Gehirn extrem” was released in 2019, with excellent illustrations by Anna Farell, twoof whichareincluded in this eBook as well. With German-speaking friends in the diving community, the book was well received, and many non-German-speaking diving friends nudged me to release an English-language version, or especially of the diving-related chapters, and this is the eBook in front of you. I have translated the two chapters on inert gas narcosis and breath hold and added a new chapter on the connection between fear and breathing.

Just like the German original “Gehirn extrem,” this is not a user manual on how to avoid inert gas narcosis when diving or how to hold your breath longer. But I think it’s the enlightened thing to try to understand what is going on in our heads if our states of mind differ from their normal states. Translating my own writings was a chance to re-read them. I’m usually a harsh critic of myself, but I am somewhat pleased: The mix between first-person “trip report” and objective neurobiological knowledge goes down easily. On top of that I present knowledge that should be well known to any trained diver, spiced up with cutting-edge and sometimes speculative neurobiological knowledge. Enjoy!

Dr. Klaus M. Stiefel

Dumaguete City, Philippines, February 2022

Divers at a depth of 50 meters on a reef in the Philippines.

Inert Gas Narcosis