Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Brendan Behan wrote over one hundred articles for Irish newspapers between 1951 and 1956 as he rose to international fame, with most of them written in a weekly column in the Irish Press. The articles reveal a serious writer capable of great comic set pieces and amusing yarns as well as thoughtful reflections on cultural and historical issues. They reflect his passion for working-class Dublin life and the history and folklore of the city, as well as his travels in Ireland and Europe. This edition gathers all the articles and essays that Behan published in newspapers from 1951 to his death in 1964. Selections of Behan's articles have been published since his death (Hold Your Hour and Have Another, 1965; After the Wake, 1981; The Dubbalin Man, 1997). However, there has been no complete edition of Behan's prose, and no edition has provided a detailed biographical and literary introduction, explanatory notes and suggestions for further reading. This volume is intended for publication during the centenary celebrations of Behan's birth in 2023, with his birthday being 9 February.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 635

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

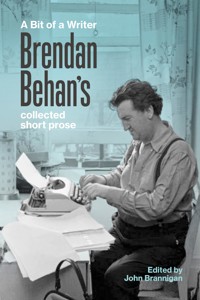

A Bit of a Writer

Brendan Behan’s

collected short prose

A Bit of a Writer

Brendan Behan’s

collected short prose

Edited by John Brannigan

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

First published 2023 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road, Arbour Hill

Dublin 7, Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

Copyright © 2023 The estate of Brendan Behan

Introduction © John Brannigan

ISBN 978 184351 8594

eISBN 978 184351 8822

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Lilliput Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon.

Set in 11pt on 15pt Caslon by iota (www.iota-books.ie) Printed in Kerry by Walsh Colour Print

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Further Reading

Chronology

A Note on the Text

1. TO THE MOUNTAINS BOUND

2. WICKLOW SAILORS AND BOYS OF WEXFORD

3. TWO MEN FROM THE NORTH

4. JOURNEY IN THE RAIN TO WATERFORD

5. JOURNEY TO THE JEWEL OF WICKLOW

6. OVER THE NORTHSIDE I WAS A CHISLER

7. THE LONG JUMP TO ARAN

8. THESE FISHERMEN PUBLICISE GAELIC AT ITS BEST

9. TRAVELLING FOLK MEET A LANGUAGE PROBLEM IN THE WEST

10. SAVED FROM CERTAIN DEATH BY THE ISLANDERS

11. BELFAST WAS FIRST RIGHT … AND THEN JUST STRAIGHT AHEAD

12. WE CROSSED THE BORDER

13. TORONTO SPINSTER FROWNED

14. TURNIP BOAT

15. TOO OLD TO SOLVE THE POSITION

16. BIGOTRY

17. SPRING

18. PARIS

19. LET’S GO TO TOWN

20. TO DIE WITHOUT SEEING DUBLIN!

21. FLOWERS ARE SAFE AT DOLPHIN’S BARN

22. UISCE, AN EADH?

23. SWINE BEFORE THE PEARLS

24. HERE’S HOW HISTORY IS WRITTEN

25. THE ROAD TO CARLISLE

26. VIVE LA FRANCE

27. HERO OF THE GODS

28. SERMONS IN CATS, DOGS – AND MICE

29. MEET A GREAT POET

30. FROM DUBLIN TO LES CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES

31. THE ROAD TO LYON

32. AHEAD TO THE SUN: FROM LYON TO THE OCEAN

33. TERROR IN THE ALPS OF FRANCE

34. THREE CELTIC PILLARS OF CHARITY

35. WHAT ARE THEY AT WITH THE ROTUNDA?

36. VOICE LIKE A CINDER UNDER A GATE

37. THE BEST RED WINE

38. BEANNACHT LEAT A SHOMAIRLE MHIC SHEOIN

39. DON’T ASK ME THE ROUT

40. THOUGHTS BEFORE ALBERT MEMORIAL

41. WE TOOK OVER A CASTLE

42. HOW SORRY THEY ARE TO RETURN

43. I MEET THE HYPHENATED IRISHMEN

44. TIME I MET A SHEIK

45. LANE PICTURES

46. PEADAR KEARNEY BALLAD MAKER

47. TRAILS OF HAVOC

48. HE WAS ONCE CRIPPEN THE PIPER

49. THE NORTHSIDE CAN TAKE IT

50. TOUR OF NATION VIA THE TOLKA

51. HEART TURNS WEST AT CHRISTMAS

52. THOSE DAYS OF THE GROWLER

53. A PICTURE OF DUBLIN’S OLD VOLTA CINEMA

54. UP CORK – FOR WIT, AND SONG

55. ON ROAD TO RECOVERY

56. I HELP WITH THE SHEEP

57. THEY DIDN’T MAKE THE FAMINE

58. YES, QUARE TIMES

59. REMEMBER DUCK-THE-BULLET?

60. EXCUSE MY MISTAKE

61. ‘I’M BACK FROM THE CONTINONG’

62. NORTHSIDERS, DON’T MISS THIS BOOK

63. WE FELL INTO THE WAXIES’ DARGLE

64. THE FAMILY WAS IN THE RISING

65. A GLORIOUS SPRING

66. DUBLIN IS GRAND IN THE SUN

67. ON ROAD TO KILKENNY

68. MAIR A CHAPAILL AGUS GHEOBHAIR FÉAR

69. FROM TOLSTOY TO CHRISTY MAHON

70. ‘O, TELL ME ALL ABOUT THE … RIOTS’

71. IT’S TORCA HILL FOR BEAUTY

72. UP THE BALLAD SINGERS

73. INVINCIBLES WERE PART OF THE FENIANS

74. ON THE ROAD TO KINCORA

75. ‘YOU AND YOUR LEINSTERMEN’

76. DANCE FOR LIBERTY

77. ADVICE FROM AN EMIGRANT

78. THE TALE OF GENOCKEY’S MOTOR CAR

79. THE TINKERS DO NOT SPEAK IRISH

80. NUTS FROM THE CRIMEAN WAR

81. TIPPERARY SO FAR AWAY

82. THE TIME OF THE FIRST TALKIE

83. OUR STREET TOOK A DIM VIEW …

84. WE DIDN’T TAKE IT BADLY

85. I’M A BRITISH OBJECT, SAID THE BELFAST MAN

86. ELEGY ON THE DEATH OF MOBY DICK

87. RED JAM ROLL THE DANCER

88. A WORD FOR THE BRAVE CONDUCTOR

89. OUR BUDDING GENIUS HERE

90. MUSIC BY SUFFERING DUCKS

91. FOR CAVAN, TURN RIGHT AT NAVAN

92. THE SCHOOL BY THE CANAL

93. THE FUN OF THE PANTO

94. A TURN FOR A NEIGHBOUR

95. NOT ANOTHER WORD ABOUT TURKEY

96. OVERHEARD IN A BOOKSHOP

97. THE HOT MALT MAN AND THE BORES

98. MY GREAT RED RACING BIKE

99. DIALOGUE ON LITERATURE AND THE HACK

100. EMANCIPATION PARSON: SYDNEY SMITH

101. REFLECTIONS ON ‘VITTLES’

102. A SEAT ON THE THRONE

103. SNOW THROUGH THE WINDOW

104. POLAND IS THE PLACE FOR FUR COATS

105. UP AND DOWN SPION KOP

106. SHAKE HANDS WITH AN ALSATIAN

107. MY FATHER DIED IN WAR

108. THAT WEEK OF RENOWN

109. A WEEKEND IN THE FOREIGN LEGION

Notes

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have been promising this collection of Brendan Behan’s articles to fellow Behan scholars and fans for some time now, and I have benefited along the way from much encouragement, support and advice. Andrew McNeillie showed me how to do it when he edited Behan’s Aran articles for the Irish University Review in 2014, and has been a generous and passionate advocate for this volume ever since. Antony Farrell has been the most patient editor and guide, and I am deeply grateful for his immediate and unwavering support for the volume.

My main reason for collecting these articles in one volume is to show Behan’s devotion to writing and his passion for people. It has been a pleasure to share this admiration of Behan’s literary talents with many other scholars and fans. I have been fortunate to learn much from the work of Deirdre McMahon, whose doctoral thesis on Behan’s work in relation to European modernism, and particularly on his time in Paris, is meticulous and inspiring. I am grateful to Trevor White and Simon O’Connor for their generous invitations to speak at the Little Museum in Dublin, and it has been a pleasure to continue to work with Simon now at the Museum of Literature Ireland (MoLI). John McCourt generously gathered a joyous coterie of Behan scholars in Rome in 2014 and then shared our work in a landmark volume, Reading Brendan Behan (Cork University Press, 2019).

I have been greatly encouraged by the support of the Behan family. I am very grateful to Blanaid Walker for her kind words of support and enthusiasm. It has been a pleasure to meet Janet Behan and many other Behans, along with their Kearney and Furlong relations, at book launches and readings over the years, and to hear their stories of this amazing family.

The annotations were enormously enhanced by the translations from the Irish by Ceithleann Ní Dhuibhir Ní Dhúlacháin. Thanks to Ceithleann for her diligent and sensitive translations of Behan’s frequent passages of Irish proverbs, phrases and songs.

The love and support of my wife, Moyra, and our three children, Conor, Owen and Laura, is central to everything, of course. They have listened to many Brendan Behan stories over the years, and will now be able to read those stories for themselves.

INTRODUCTION

Before Brendan Behan became famous internationally as a playwright and bohemian reveller, he wrote a weekly newspaper column in Dublin for The Irish Press. Between 1953 and 1956 he produced over one hundred articles. Some were recollections of his childhood in Northside Dublin, some were inventive comic fictions, some told the stories of his travels and musings around Ireland and Europe. He had begun to write these articles on an occasional basis in 1951, but they became a regular feature in late 1953 when the new editor, Jim McGuinness, commissioned him to write a weekly column. McGuinness had known Behan in the 1940s – both men were interned in the Curragh military camp as IRA activists during the Second World War. When he became editor of The Irish Press, McGuinness set out to bring more writers to the newspaper for feature articles and columns. It is evidence of the impact that Behan had already had as a young writer that McGuinness chose to ask him alongside more established writers such as Lennox Robinson and Francis MacManus. By this time, Behan had published a handful of short stories in English, and some poems in Irish, as well as a serialized novel, The Scarperer, which was published under a pseudonym, ‘Emmet Street’, in The Irish Times. He had also written radio plays and presented radio broadcasts for Raidió Éireann. In 1954 his first major play, The Quare Fellow, had its premiere in Dublin’s Pike Theatre; by 1956 the play had made him an international star. The columns published in The Irish Press were written in the period in which Behan achieved his first success, and in which he was at his most confident and conscientious as a writer.

‘Brendan wrote his newspaper articles with ease,’ wrote his wife, Beatrice, ‘rarely missing a deadline.’ He was paid five pounds a week and given free rein to write about whatever he chose. He rose early, and would write until it was time to bring Beatrice breakfast in bed. It was a routine not completely without interruptions, for he would occasionally go off on drinking binges, but he usually found ways of making the deadline. Donal Foley, who worked in the London office of The Irish Press, recalled how Behan turned up at the office one day to ask for an advance of twenty pounds. The editor allowed Foley to give Behan the money on condition that he first received four articles. Four hours later Behan returned with four articles amounting to seven thousand words, and was paid the money. Behan’s column, Foley writes, was ‘the best of its kind to appear anywhere at that time’, and the four articles, hastily written as they were, lived up to expectations.

In later years, wracked with illness, Behan seemed to resent the fact that Dubliners were slow to recognize his talents. His most significant achievements in literature found success and recognition elsewhere. The Quare Fellow was rejected by the Abbey Theatre and performed only in the Pike, a small experimental theatre, before it became an international success after its West End production in London in 1956. The Hostage first found expression in an Irish-language version, An Giall, performed in the modest setting of Damer Hall in Dublin, but then likewise became a West End and Broadway success in 1958. Borstal Boy, his autobiographical novel, was banned in Ireland as soon it was published in the same year. Lionized by theatre audiences in England, America and Europe, and courted by journalists and broadcasters wherever he went, Behan felt shunned by his peers in Ireland. In an interview with Eamonn Andrews, broadcast on RTÉ in 1960, Behan’s resentment was palpable: ‘The Irish are not my audience; they are my raw material,’ he professed. When Andrews asked if he would like the Irish to be his audience, Behan replied, ‘No, I don’t care. I don’t care.’

Behan did care. In the articles gathered here, it is clear that he cared deeply about Dublin and Dubliners. He cherished the stories, songs and sayings of the people who surrounded him in his childhood and youth. There is a prevailing sense of nostalgia for the receding generations and communities of the early twentieth century – the rebels of 1916, the veterans of the Boer War and the First World War, and the oul’ ones whose sharp wit and quick tongues deflated the pomposity of both the rebels and the veterans. There is also a lively sense of community with contemporary Dubliners – Behan has much to say about changes in the city, and responds to his correspondents in his column. Behan attempted to produce in his column a sense of Dublin as a ‘knowable community’, a place that abounded with jovial rivalries between distinct areas (‘Monto’ and the ‘Coombe’; the Northside and the Southside), but ultimately a city in which it was impossible to get lost. In his comic sketches, and the characters he invented for them – Mrs Brennan, Maria Concepta, Crippen – he conjured up the distinctive dialectal style and conversational rhythms of Dublin speech, and a strong sense of identity and outlook. ‘The Dubliner is the victim of his own prejudices,’ writes Behan, but in these articles he satirizes those prejudices tirelessly, writing that he had been ‘conditioned all the days of my life to the belief that people from the three other provinces, Cork, the North and the Country, could build nests in your ear, mind mice at a crossroads, and generally stand where thousands fell’.

It is, then, as a ‘jackeen’, a Dubliner seen as if from outside, that Behan also takes his readers on a tour around Ireland – to Wicklow and Wexford, to Kerry, Connemara and the Aran Islands, to Belfast and Donaghadee. These outings are no mere travelogues or tour guides. He is rarely interested in the ‘sights’; instead, Behan displays the same warm curiosity and interest in people and their stories wherever he goes. The same is true of his adventures across the sea to France, and particularly to Paris, a place dear to his heart since the late 1940s. ‘Everyone admires Paris for the artists,’ he wrote, ‘but I equally loved Paris for the barricades.’ In truth, literature and politics are intertwined and inseparable sources of interest for Behan. The pieces abound in allusions to writers and artists, and perhaps even more so to the architects and activists of Irish republicanism. We find in them stories of Brendan Behan passing himself off as George Orwell, and stories about Yeats, Joyce and O’Casey. The pantheon of Irish heroes, from Brian Boru to Patrick Pearse, is never far from his thoughts. Yet perhaps Behan’s greatest gift is to give no more significance or weight to the stories of these famous figures than to the stories of his family and neighbours. Behan was a folk writer, in the best tradition of folk tales and folk songs, a collector and teller of stories.

LIFE AND WORK

Brendan Behan was born on 9 February 1923, just six months after his parents, Stephen Behan and Kathleen Kearney, had got married. Stephen was a house-painter by trade, a passionate reader of literature, and a republican and trade union activist. At the time of Behan’s birth, his father was imprisoned in Kilmainham Jail for opposing the treaty with Britain signed by the new Irish Free State. Brendan Behan would follow his father’s literary and political interests closely, and for a time also followed his father into the house-painting trade. Kathleen had been married previously to Jack Furlong, a Belfast republican who died of influenza in 1918, with whom she had two sons. A committed republican herself, Kathleen had worked in domestic service for Maud Gonne MacBride, and knew many of the most significant political and cultural figures of the Irish revolutionary period, including W.B. Yeats and Michael Collins. She had a deep knowledge and wide repertoire of Irish folk songs, with which she entertained her children. Her brother Peadar Kearney wrote the Irish national anthem, among many other songs. Her brother-in-law was the actor and theatre manager P.J. Bourke. The Behan family, which included Brendan’s two half-brothers, Rory and Seán Furlong, and later three brothers, Seamus, Brian and Dominic, and a sister, Carmel, lived in tenement rooms in 14 Russell Street in Dublin.

Russell Street, in the shadow of the national Gaelic sports stadium, Croke Park, beside the Royal Canal and adjoining the North Circular Road, is the scene of many pieces here. The street contained a row of Georgian houses, once the home of middle-class families, which had long become tenement houses with rooms rented out, and whole families living in one room. Behan describes these houses often, with families living cheek by jowl, doors always open, children running errands for bed-bound elders, with nowhere and no time for peace and quiet. The characters, the stories and the songs from this upbringing were the sources of his art. Almost all the men that Behan knew as a child had been to war, to prison, or both. The women learned how to survive and endure. Behan attended St Vincent’s Boys’ School on North William Street just a few streets from his home, run by Catholic nuns, the French Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul. He also joined the Fianna, the youth wing of the IRA, at the age of eight, and his first publication – at the age of thirteen – was in the organization’s newspaper, Fianna Éireann. As a child he was deeply aware of the deeds of Irish nationalists but even more of their words. He recalled being able to recite the famous speech from the dock by Robert Emmet from the age of six.

Behan’s education continued at the Christian Brothers’ school, St Canice’s, on the North Circular Road, from 1934 to 1937. When he left the school, aged fourteen, he followed his father into the painting trade, and took day courses in sign-writing and decorating at Bolton Street Technical School. Political activities took precedence over work and in 1937 he tried to enlist with other Irish republicans in the International Brigades going off to fight against fascists in the Spanish Civil War. He was refused because of his age, and with his brothers resorted to organizing support for the Spanish republican cause in Dublin. In the same year the Behan family was moved out of Russell Street. In response to worsening slum conditions in inner-city Dublin, the Irish government had issued decrees to clear the slums and relocate people to new council-owned houses in the suburbs. The Behans were moved to 70 Kildare Street in Crumlin. It was a house of their own, a step up from tenement living, but the family struggled to warm to their new surroundings. Brendan, in particular, was lost without the sense of close community he had clearly so enjoyed in Russell Street. He became more and more committed to IRA activities, including training as a bomb-maker.

With a suitcase full of bomb-making equipment, Brendan Behan departed from Kildare Street on 30 November 1939, and took the boat to Liverpool. The IRA, under the new militant leadership of veteran Seán Russell, had embarked on a callous and ham-fisted campaign to bomb targets in Britain, supposedly to compel the British government to cede Northern Ireland to Irish rule. Behan claimed later that his target was a battleship in Liverpool docks, although most targets of the campaign were either intentionally or accidentally civilian. Behan’s mission was foiled almost immediately – he was arrested within hours of getting off the boat. As a juvenile, Behan could only be sentenced to borstal detention by the court, and so began Behan’s long familiarity with incarceration. His experience of English jails and borstals became the subject of perhaps his most famous work, the autobiographical novel, Borstal Boy, published in 1958. Borstal detention was a relatively positive experience for Behan. He enjoyed the company of other working-class boys and found that, despite his political convictions, he had many things in common with them. He also benefited from a relatively liberal system in which he was encouraged to read, write, perform in plays and enter writing competitions.

Behan was released from borstal and deported from Britain in December 1941, but he was barely a few months back in Dublin when he found himself in prison again. At a republican commemoration ceremony in April 1942 he fired a revolver at two detectives. When he was captured, under legislation introduced to crack down on IRA activities in neutral Ireland at a time when the rest of Europe was at war, he could have been sentenced to death for his actions. Instead, possibly because his father had once shared a prison cell with the man who was now the Minister for Finance, Seán T. O’Kelly, and intervened for his son’s life, Brendan was tried and sentenced to fourteen years in prison. He spent time in Mountjoy, Arbour Hill and the Curragh military prison, during which time he came to know and benefit from friendships with several writers. Seán Ó Faoláin, one of Ireland’s leading writers at the time, took an interest in Behan and published his first serious piece of literary writing, ‘I Become a Borstal Boy’, in the most significant Irish literary magazine of the day, The Bell. During this time Behan also began writing early versions of both Borstal Boy and The Quare Fellow, as well as other works that have subsequently been lost.

In 1946 IRA prisoners held in Irish jails were released on general amnesty. Behan would go back to prison on several subsequent occasions for disorder and breaking deportation orders. However, while he returned to employment as a house-painter, albeit fitfully, he was now dedicated to becoming an established writer. He spent much of the late 1940s in Paris, a city where he got to know Albert Camus, James Baldwin and many others. For much of this time he lived in poverty, but began to publish some of his most daring work in Points magazine, edited by Sindbad Vail, the son of Peggy Guggenheim. On his return to Dublin in 1951 Behan began to publish articles in The Irish Press. This was the beginning of his most sustained period of development as a writer.

Over the next few years, he experimented with writing for theatre, magazines, radio and newspapers, and across a wide range of styles and genres. He became well established in Dublin’s literary and artistic scene, principally based in the city’s pubs. Here he socialized with Flann O’Brien, Anthony Cronin, John Ryan, and J.P. Donleavy, although others, notably Patrick Kavanagh, steered clear of his company. In 1955 he married the artist Beatrice Ffrench Salkeld, and their relationship was key to the brief period in which Behan worked most diligently as a writer. His first major success came in 1956, when Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop in London agreed to produce The Quare Fellow. Behan’s play evolved through a number of iterations in the Irish language, and had been sent to the Abbey Theatre and rejected before being performed first in Dublin in the Pike Theatre in November 1954. The play was a critical success in Dublin, but its London performance catapulted Behan to fame. He became the subject of television interviews, feature articles and newspaper headlines. The Quare Fellow was quickly followed by the even greater success of The Hostage. Behan first wrote The Hostage as an Irish-language play, An Giall, for the organization that promoted the language, Gael Linn. Revised into English for Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop, The Hostage performed to rave reviews in October 1958, the same month in which Behan published Borstal Boy, and in June 1959 transferred to the West End. Behan was lauded by the British press, but this was nothing compared to his reception in New York when the play was performed there in 1960.

The story of Behan’s rise and fall is well known – celebrity killed him. His newfound wealth became increasingly based on appearances, interviews and publicity. The performances were followed by parties, and Behan’s addiction to alcohol had a detrimental effect on his health and on his ability to write. In the early 1960s he spent months at a time in New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. He befriended some of the most famous writers and artists of the time, including Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Allen Ginsberg, Groucho Marx, Norman Mailer, Jackie Gleason and others. He was offered no end of commissions to write screenplays and books. By 1962, however, alcoholism had quelled his ability to write. His remaining publications – Confessions of an Irish Rebel, Brendan Behan’s Island and Brendan Behan’s New York – were dictated to a tape recorder and edited and transcribed for publication by Rae Jeffs. He suffered diabetic seizures, and was warned that excessive drinking could be fatal. A return to Ireland and the birth of his daughter, Blanaid, seemed to offer a glimpse of hope, but he died in a coma in hospital on 20 March 1964 from liver failure. A number of works were unfinished at the time of his death. He had been working on a novel called The Catacombs since the late fifties and started a new play, Richard’s Cork Leg, eventually completed by Alan Simpson and performed in 1972. Both contain something of the exuberance and ingenuity of Brendan Behan, but neither lives up to what he wrote in the early 1950s.

BEHAN IN HIS OWN TIME

Brendan Behan’s life (1923–64) coincided with the foundation and consolidation of the new Irish state. When he was born, the country was divided as to whether the independence won from Britain in 1922 was acceptable without the six counties of the North that remained under British rule. His father was committed to the anti-treaty position, and was jailed for his rebellion against the new state. From an early age, Brendan Behan was an active member of republican organizations dedicated to fighting for a united Ireland. His commitment to Irish republicanism was based on political dissent from the acceptance of partition, and from the conservatism of the Irish Free State. It was also marked, however, by a profound sense of belatedness. The IRA to which he committed himself was a shadow of the body that had fought the 1916 Rising and the War of Independence, even though veterans of both campaigns led the organization in the 1930s and 1940s. Behan’s writings abound with nostalgia for events that occurred before his birth:

When I was nine years old I could have given you a complete account of what happened from Mount Street Bridge out to the Battle of Ashbourne, where I was giving Tom Ashe and Dick Mulcahy a hand. I could tell you how Seán Russell and I stopped them at Fairview, and could have given you a fuller description of Easter, 1916 than many an older man. You see, they were mostly confined to one garrison – I had fought at them all.

The events and personalities of the war against Britain loom large in Behan’s writings, and extend well beyond those of the twentieth century to the Fenians and the United Irishmen. For Irish republicans of Behan’s generation, the new state did not represent the liberation for which they had fought. Behan felt that the Irish state simply took over the reins of government, but for working-class Irish people nothing changed.

For much of the 1930s the IRA leadership was influenced by socialist ideas. Behan supported socialist and communist organizations throughout his life. In the late thirties the departure of many left-wing IRA volunteers to fight in the Spanish Civil War resulted in a shift in the political orientation of the IRA towards a more orthodox and militant position. The new leadership embarked on a deadly campaign of bombing targets in Britain at exactly the time when Britain was becoming the bulwark of opposition to fascism in Europe. By the time Behan got involved in the IRA campaign in late 1939, its new leader, Seán Russell, whom Behan admired for his role in the 1916 Rising, was seeking support from Nazi Germany. While in jail in England, Behan became conscious of the growing gap between his own political beliefs and the organization of which he was a member and increasingly saw writing rather than politics as his calling. By the mid-1950s, writing the column for The Irish Press, he was the subject of British intelligence files for his communist sympathies and his literary connections with left-wing writers and artists rather than his IRA connections.

Ireland was neutral during the Second World War, and Behan spent most of it incarcerated first in England and then in Ireland. The Dublin he rediscovered in the late 1940s was still marked by the same poverty and insularity that had defined his childhood years. Yet there were signs of change. Culturally, writers and artists were tilted towards continental Europe. Envoy magazine, edited by his friend John Ryan, and in which Behan was published, was a key cultural expression of this affinity with European literature. As Behan recounts in some of the articles in this volume, he spent much of the late forties and early fifties in Paris and travelling around Europe. Paris, in particular, was a city of great attraction. It was linked, obviously, to the great modernist writers of the previous generation – Joyce, Hemingway, Proust and Stein – but it was also a city of writers exploring what art meant in a new post-war world. Behan came to know Albert Camus well; he was regarded affectionately, if rather tolerantly, by Samuel Beckett; and he was amused to share the same café as Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. His plays, perhaps particularly The Quare Fellow, share some of the key preoccupations of these writers with the meaning and value of human existence and the problem of ethical action in a world seemingly devoid of beliefs or principles. Paris also afforded Behan the opportunity to express himself in ways not possible in Ireland – it was in the Paris-based literary magazine, Points, that Behan wrote about homosexuality in ‘After the Wake’, and in an early version of Borstal Boy called ‘Bridewell Revisited’.

In The Irish Press, of course, Behan could not risk writing about subjects that were likely to result in censure or dismissal. He was well aware of the bounds of acceptability in mid-century Ireland. He knew them since childhood – he once wrote in a letter of how he had received ‘a kick in the neck’ from a teacher for answering in the affirmative to the question ‘Could Ireland become communist?’ In Borstal Boy he did not include those passages in which he was most explicit about homosexuality and permitted the publisher to replace expletives, yet still the book was banned. He chafed against the stifling strictures of conservative Ireland. ‘Sometime I will explain to you the feeling of isolation one suffers writing in a Corporation housing scheme,’ he wrote to Sindbad Vail in 1951. ‘Cultural activity in present day Dublin is largely agricultural. They write mostly about their hungry bogs and the great scarcity of crumpet.’ In response, Behan wrote these articles as an unashamed ‘city rat’, determined to celebrate the culture of working-class Dublin.

Things were changing for the Dublin that Behan knew. It could be argued that Behan’s depiction of Dublin life in these articles was already belated, describing a city and a culture that was in the process of disappearing. The tenement flats had been cleared to make way for corporation houses. The songs about Kevin Barry and Spion Kop were being replaced by rock and roll and Teddy Boys. Behan is clear-eyed about such changes, and did not approve of preserving the ‘old’ Dublin for the sake of tourists from Foxrock or Chicago: ‘God knows life is short enough,’ he wrote, ‘without people wearing themselves out hauling prams round lobbies, so that we can know what Hardwicke St. looked like in 1790.’

The new houses in Crumlin may not have been to his liking, but he recognized that they were attempts to improve the conditions of working-class Dubliners. That the old Dublin produced a culture he depicts as one of vibrancy, wit and song was not an argument for keeping people in the same slum conditions they had endured for decades. By the time Behan died in 1964, a process of economic liberalization had begun that prepared the way for Ireland to join the European Economic Community in 1972 and, some have argued, to become a modern, prosperous state. We will never know how an older Behan, in his fifties and sixties, might have responded to the war in Northern Ireland; nor, if he had lived to his eighties, what he would have made of the so-called ‘Celtic Tiger’. The articles collected here, however, allow us to enjoy Behan in his own time.

FURTHER READING

BRENDAN BEHAN’S WRITINGS

The Complete Plays (London: Methuen, 1978)

Borstal Boy (London: Hutchinson, 1958)

Poems and a Play in Irish (Oldcastle, Ireland: The Gallery Press, 1981)

Poems and Stories, ed. Dennis Cotter (Dublin: Liffey Press, 1978)

An Giall/The Hostage, ed. Richard Wall (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1987)

Confessions of an Irish Rebel (London: Arena, 1985)

Hold Your Hour and Have Another (London: Corgi, 1965)

The Dubbalin Man (Dublin: A. & A. Farmar, 1997)

After the Wake, ed. Peter Fallon (Dublin: O’Brien Press, 1981)

The Scarperer (New York: Doubleday, 1964)

Brendan Behan’s Island (London: Corgi, 1965)

Brendan Behan’s New York (London: Hutchinson, 1964)

BIOGRAPHIES

Behan, Beatrice, My Life with Brendan (London: Leslie Frewin, 1973) Behan, Brian, With Breast Expanded (London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1964)

— and Behan, Kathleen, Mother of All the Behans: The Autobiography of Kathleen Behan as Told to Brendan Behan (Dublin: Poolbeg, 1994)

— and Dillon-Malone, Aubrey, The Brothers Behan (Dublin: Ashfield Press, 1998)

Behan, Dominic, Teems of Times and Happy Returns (London: Four Square, 1963)

— My Brother Brendan (London: Four Square, 1966)

de Búrca, Séamus, Brendan Behan: A Memoir (Dublin: P.J. Bourke, 1993)

Jeffs, Rae, Brendan Behan: Man and Showman (London: Corgi, 1968)

McCann, Seán (ed.), The World of Brendan Behan (London: Four Square, 1965)

Mikhail, E.H. (ed.), Brendan Behan: Interviews and Recollections (London: Macmillan, 1982)

— (ed.), The Letters of Brendan Behan (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992)

O’Connor, Ulick, Brendan Behan (London: Abacus, 1993 [1970])

O’Sullivan, Michael, Brendan Behan: A Life (Dublin: Blackwater Press, 1997)

Ryan, John, Remembering How We Stood: Bohemian Dublin at the Mid-Century (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1975; The Lilliput Press, 2008) Simpson, Alan, Beckett and Behan and a Theatre in Dublin (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1962)

Uíbh Eachach, Vivian and Ó Faoláin, Dónal (eds.), Féile Zozimus: Volume 2 – Brendan Behan: The Man, the Myth, the Genius (Dublin: Gael Linn, 1993)

CRITICISM

Boyle, Ted E., Brendan Behan (New York: Twayne, 1969)

Brannigan, John, Brendan Behan: Cultural Nationalism and the Revisionist Writer (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2002)

— (ed.), Brendan Behan (Special Issue), Irish University Review, vol. 44, no. 1 (Spring 2014)

Gerdes, Peter René, The Major Works of Brendan Behan (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1973)

Kaestner, Jan, Brendan Behan: Das dramatische Werk (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1978)

Kearney, Colbert, The Writings of Brendan Behan (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1977)

McCourt, John (ed.), Reading Brendan Behan (Cork: Cork University Press, 2019)

Mikhail, E.H. (ed.), The Art of Brendan Behan (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1979)

— Brendan Behan: An Annotated Bibliography of Criticism (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1980)

Porter, Raymond J., Brendan Behan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1973)

CHRONOLOGY

1923 Brendan Behan born 9 February to Kathleen (née Kearney) and Stephen Behan. The Behan family live in a tenement flat in 14 Russell Street, Dublin.

1928–34 Attends St Vincent’s School, North William Street, Dublin.

1931 Joins Fianna Éireann (IRA Youth Movement).

1934–7 Attends St Canice’s Christian Brothers’ School, North Circular Road, Dublin.

1936 Behan publishes his first piece of writing, ‘A Tantalising Tale’, in Fianna: The Voice of Young Ireland ( June).

1937 Attends Bolton Street Technical School to learn the trade of house-painting. The Behan family are rehoused by the Dublin Corporation in 70 Kildare Road, Crumlin, in a new housing estate.

1939 Brendan Behan joins the IRA. He is arrested in Liverpool, 1 December, on charges of possession of explosives and held in custody in Walton Jail.

1940 Behan sentenced to three years’ borstal detention, 8 February, and moved initially to Feltham Boys’ Prison, then to Hollesley Bay Borstal, where he is imprisoned until his release and expulsion to Ireland on 1 November 1941.

1942 Behan arrested for shooting at Dublin detectives, 10 April, and sentenced to fourteen years’ penal servitude. He is imprisoned in Mountjoy Prison, then Arbour Hill Prison from July 1943 and the Curragh Camp from June 1944, until his release under general amnesty in September 1946. ‘I Become a Borstal Boy’ published in The Bell ( June).

1947 Behan visits the Blasket Islands, Kerry ( January). He is arrested and imprisoned in Strangeways Prison for three months for breaking his expulsion order (March–July). On his return to Dublin Behan begins to frequent ‘The Catacombs’ in 13 Fitzwilliam Place.

1948 Behan serves one month in Mountjoy Prison, Dublin, for assaulting a policeman. He goes to live in Paris in August and stays there until 1950, with only brief visits to Dublin and Belfast. In Paris, he lived on rue des Feuillantines, initially staying with Samuel Beckett’s cousin John at the Grand Hôtel des Principautés Unies, and frequented the Left Bank and Les Halles.

1950 ‘A Woman of No Standing’ published in Envoy, the Dublin magazine edited by John Ryan. ‘After the Wake’ published in Paris in Points (December), an avant-garde literary magazine edited by Sindbad Vail.

1951 ‘Bridewell Revisited’, an early draft of the opening of Borstal Boy, published in Points (Winter). From around this time, Behan abandons house-painting as his trade and devotes himself to writing, and his income mainly comes from The Irish Press, The Irish Times and Raidió Éireann until his rise to fame in 1956.

1952 Behan recounts his Parisian experiences in a radio talk for Raidió Éireann on 29 March. In the summer Behan lives in an IRA safe house in Wicklow while writing parts of Borstal Boy. He serves one month in Lewes Prison, Sussex, for breaking an expulsion order (October). On release in November he goes to Paris to visit Samuel Beckett.

1953 The Scarperer is published serially in The Irish Times, beginning on 19 October. Behan writes the serial parts on the Aran islands.

1954 Behan writes a weekly column for The Irish Press, April 1954 to April 1956. The expulsion order against him in Britain is revoked. The Quare Fellow opens at the Pike Theatre, Dublin, on 19 November.

1955 Behan marries Beatrice Ffrench-Salkeld, 16 February.

1956 The Quare Fellow opens at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, London, 24 May. Borstal Boy published serially in the Irish edition of the Sunday Dispatch.

1958 Brendan and Beatrice go to Ibiza for three months. An Giall opens at the Damer Hall, Dublin, 16 June. Goes to Sweden in August to translate An Giall into The Hostage. The Hostage opens at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, London, 14 October. Borstal Boy is published by Hutchinson (London) on 20 October. The Quare Fellow produced off-Broadway.

1959 The Quare Fellow produced in Berlin, which Behan attends. Behan goes to Paris (April) for the performance of The Hostage at the Théâtre des Nations Festival. Behan suffers epileptiform seizures ( July).

1960 The Hostage is performed in the Cort Theatre, New York. Behan makes his first visit to America, where he spends much time over his last few years.

1961 ‘The Big House’ published in Evergreen Review (October).

1962 Brendan Behan’s Island published (October).

1963 Hold Your Hour and Have Another published (September). Behan’s daughter, Blanaid, is born, 24 November.

1964 Brendan Behan dies at the Meath Hospital, 20 March. The Scarperer published ( June). Brendan Behan’s New York published (September).

1965 Confessions of an Irish Rebel published (September).

1972 Richard’s Cork Leg opens at the Peacock Theatre, Dublin, 14 March.

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

Most of the articles published in this edition were first published in The Irish Press newspaper between 1954 and 1956, when Behan was commissioned to write a weekly column for the newspaper. The column appeared every Saturday, almost without fail, for two years. The articles are arranged in chronological order. This is to preserve the ways in which Behan followed the same theme, story or journey over successive weeks.

There have been three selected editions of Behan’s writings: Hold Your Hour and Have Another (Hutchinson, 1963), After the Wake, edited by Peter Fallon (O’Brien Press, 1981) and The Dubbalin Man (A. & A. Farmar, 1997). This volume provides the first complete edition of Behan’s weekly pieces for The Irish Press and a small number of articles published in other newspapers. Errors have been corrected but in all other respects the texts have been maintained as they first appeared. Behan’s spelling of Irish language words and phrases sometimes differ from modern usage, but original spellings have been preserved here.

Collected Articles

1

TO THE MOUNTAINS BOUND

Brendan Behan heads from Dublin to Wicklow on the first steps of the road round Ireland.

The boss on the painting job says to me one morning: ‘Behan, I believe you are a bit of a writer.’

Remembering: ‘Mr Behan handles a delicate subject with sensitivity and taste, permitting but a negligible excess towards the end; he has the rare gift of knowing when to restrain his narrative and when to let it go forward so that his tensions are always controlled and his irony never heavy-handed; but above all he has inherited the virtue of his race of writing as he talks and talking as he sings in word arrangements, sensuous, syntactical.’ (The Hudson Review,1 New York, Summer, 1951.) I modestly assent.

‘Well, write this.’ And he hands me a time-sheet.

I fill it in. Syntactically. ‘Assisting generally inside. Twelve hours.’ Sensuously. ‘Plus two hours travelling time.’

‘And take these.’ He hands me my three cards. Unemployment Insurance, Wet-Time2 and National Health. One to go away, the second to stay away, and the third not to come back.

I depart from the job and am no longer a force in contemporary painting. Like a stricken deer I wander to the shelter of Grafton Street.

Having passed a good many places on the way down town, my fourteen hours was sadly reduced to minutes by the time I reached the corner of South King Street.

Paddy, behind the bar, looked up from his polishing and said: ‘I thought you were down the country.’ He is the only Dubliner in the business.

‘Well, I’m back.’

‘Glad to see you safe home any way, Brendan.’

‘Thanks, Paddy, I know you mean that.’ I had been in Maynooth for one day.

‘Where are you going now?’

‘I am going for a walk in the sun.’

‘The Lambs? The Dead Man’s?’

‘No. Further than that. Out of reach of this city altogether.’

‘You’re not thinking of the turf, are you. Though I hear there’s clerical students and all at it these times.’

‘I’m going to travel Ireland, all Ireland.’

‘Belfast?’

‘Yes.’

‘And Cork?’

‘Yes.’

‘God bless us and save us.’

‘Here’s a lift for you now, anyway, Brendan and Jemmy. The other Brendan, the Wicklow one.’

‘Me sound man,’ says the Wicklow one. ‘We were just looking for you. I’m delighted I got you, Brendan, before I left town. Any man that died for Ireland, like yourself, it’s a bare-faced pleasure to treat you.’

‘I don’t see how he could have died for Ireland,’ said a scorpy-looking individual with a hungry old face with a lot of character in it. ‘He’s not old enough.’

‘Ah, God help him,’ says Jemmy, indicating the other Brendan, ‘Sure you needn’t be minding him. He backed Sugar Ray against Turpin.’

‘Well,’ says Head of Character, reasonably enough, ‘the best in the world can make a mistake.’

‘Brendan,’ says Paddy the bar, ‘is fed up in the city. He’s away. Miles and miles like Kitty the Hare. All over Ireland, Belfast and Cork and all.’

‘A good start is half the work,’ says Jemmy, ‘to the Garden of Ireland3 and the finest tulip in it.’

On the way down we entertained the people, whether they liked it or not, with songs, recitations and Brendan the Wicklow one did a hornpipe with as much function and capernosity as the exigencies of the situation and the passengers’ feet in the way allowed. A man over from New Zealand said he never saw the likes of it. Not even in his own country. I had to tell him, of course, that we were not always as good as this.

In a Roundwood pub we spent a few hours and in the morning I was not in such good shape for my walk.

‘What hurry is on you,’ said Brendan the Wicklow one, ‘can’t you stop on a bit.’

‘Sure couldn’t you give a hand with the hay?’ says Jemmy.

‘And give an ould stave of a song in the evenings,’ said Charlie the Guard, more reasonably.

But I knew the best of my play was to get out of that pub that morning or I’d be there for the rest of time. So I walked three miles and, feeling the heat and burden of the day, went up to the house of a man, of the same Anglo-Irish stamp as Frank Taaffe,4 that fed poets and washed poets in the best of malt until Raftery destroyed his best hunting-horse and ruined the transaction. No one, so far, has killed a horse on this man, so he’s there to the good go maith go fóill.5

I left there the next morning and took myself to Avoca. In the bar beside Tom Moore’s tree a famous Belfast boxer and myself and some bookies and so forth, looked out at the Meeting of the Waters.6 The boxer was travelling Ireland also. But in a motor-car. It was costing him and the others a lot of money for the car and the driver, who was getting compensation, besides his wages, for not being allowed at the counter until night time. Despite this, they reckoned they were saving money by coming down, the price of drink in the North being what it is.

On the way through Rathdrum the next day a guard stopped me.

‘Hello, and how are you?’

‘Have we met before?’

‘Well, I saw you in Cork one time. In Patrick Street. You were in good form that night.’

It was possible.

‘Just out for a stroll?’

‘Hiking.’

He laughed.

‘You are not in uniform.’

I wear a fawn overcoat, a blue jacket and bawneen trousers. The latter the gift of a young Irish composer. A white shirt from Simpsons of Piccadilly kindly presented by a BBC critic late of this town, but formerly and for long enough at this caper himself.

‘What’s this the name is again?’

To save wear and tear on his politeness, I produced my labour cards, mostly innocent of stamps, North of Ireland food cards and British Mercantile Marine card, and an invitation from the French Press attaché to attend a party in celebration of the two-thousandth anniversary of Paris.

‘Good luck, old son,’ said the guard. ‘But you are going in the wrong direction.’

On the way out of town I passed the open door of the National Health agent. In the hallway hung a picture of the Irish Brigade in the Boer War7 charging the British. It was called: ‘A New Fontenoy’.

The Irish Press, 2 August 1951

2

WICKLOW SAILORS AND BOYS OF WEXFORD

Brendan Behan follows the road from Roundwood to Enniscorthy, and a poem of his own in Irish on the radio.

I got a lift from Roundwood to Arklow. In Arklow there was plenty of money stirring, judging by the pubs. But there is something very wistful about seamen, even when they are ashore enjoying themselves.

Johnson8 said of them that no man would go aboard ship who had sufficient contrivance to get himself into a jail, for to be a sailor was to be prisoner with the added risk of drowning.

I was at a hooley in Dieppe not many months ago, with Clogher Head men and Faythe men and Donal from Cork City and little Johnny from Schull, not to mention Big Mick the bo’sun and Gurrier the cook. ‘North, South, East or West, Gurrier’s coddle it is the best.’ And indeed I was head man at hooleys nearer the Point of the Wall than the Café Normandie where the drink, in quantity and variety, would have done a few hunt balls if the people that attend such things knew as much as seamen about Mumm at ten shillings and Pernod out of bond at five shillings a bottle.

Although there was one fearful Irish maritime mixture, an amalgam of every conceivable sort of spirit from Marc to Mirabelle that I wouldn’t give my worst enemy.

I walked out of Arklow and had a good bit of Wexford road over me when a man pulled up and told me to hop in. On the road to Inch we talked about one thing and another but it was only in the pub there that I discovered that I was being entertained by a former county footballer.

I knew by the tone of reverence with which the bar greeted him that he was someone a step above buttermilk. We had a discussion about the weather with the postman and a lorry driver. The postman said the heat suited him but the lorryman didn’t like it. Not when he was working anyway.

Going on to Gorey the footballer told me that the postman was well-known in his own right as a champion dancer and the finest and lightest man that ever beat timber for Irish or jazz, in the county of Wexford, where I was now and for the first time, and not a bad class of people, either, if they were all as civil as the footballer.

Gorey is a fine English-looking sort of country town. I mean that as a compliment, for most of our country towns are not very beautiful. They look like cow-towns, shoved up as trading posts for the country round. And what else were they all during our history but places where one was liable to meet landlords’ agents, rent collectors and bailiffs, and peelers standing outside a courthouse with a big crown over it just to let you know who the boss was, in case you’d forgotten since your last visit.

English villages have had more natural origins and have a more settled look about them.

There were Dublin people on holiday in it. One of them, a lad from Drumcondra, asked me if I had been buying cattle at the fair.

‘Is it codding me, you are?’

‘Oh, I didn’t hear you speak. I am sorry.’

‘I am sorry, too, that I am not buying cattle.’

‘He writes,’ says the footballer, ‘books and all.’

This was a lie. But what you do well, do it often.

‘With hard covers and all,’ says the footballer; ‘and, better still, he is going to have me in the paper.’

A tall English chap was called into the company to get very excited about this. He himself, it appeared, did a bit in that line.

‘You don’t happen to have anything of your own with you just now, do you?’ ‘Only this.’ I all unassuming produce from my overcoat pocket a copy of Down and Out in Paris and London.9

‘“George Orwell.” That’s not a terribly Irish name, is it?’

‘It’s not my real one. But it suited the English market. “George.” The King and that, you know, and “Orwell”, the River Orwell.10 I was educated in England and that river had associations for me. The “bosky glades” and so forth.’

As a matter of fact, the River Orwell flows quite near a school I was in in England.

In Enniscorthy I asked the man behind the counter if he would turn on the wireless at nine twenty. He looked at the programme in the paper.

‘It’s Irish.’

‘I know. It’s verses I wrote myself.’

While I was listening to the broadcast a man came in and stood behind me. He looked at me and said:

‘An dtuigeann tu sin?’

‘Tuige na dtiuginn, mar is mise do cheap?’

‘Maithiu, begor, is fiu deoch e is fada o bhios ag chaint le file.’11

I said I didn’t mind if I did and if all was equal to him I’d chance a half.

The Irish Press, 24 August 1951

3

TWO MEN FROM THE NORTH

Brendan Behan, on the Road Round Ireland, comes to New Ross.

Down from Enniscorthy the road is through rich, comfortable-looking land. It has the appearance of having been lived in. There are stone barns and the houses lie snug behind big trees and old hedges. Except for the smaller fields I could have imagined myself in north-west France. But I would prefer the poorer, less efficient-looking places over Wexford way.

The houses there are honestly facing the road, and you can see them at the table and be called in off the road maybe, if they thought you needed a bit. But yet these people of the Norman farmhouses were not behind the door, as the saying has it, in Ninety-Eight.12

At a lovely little Protestant church I sat down under a big tree and had a read. Some Dublin kids with whom I exchanged Jackeenisms13 any time we passed on the road cycled by.

‘Will yous look at him,’ shouts one Kimmage Commando to another, ‘with his hair in his eyes and his book in his hand, like a bloomin’ poet.’

Walking down the road came a man carrying a good raincoat, I could see the lining of it. He was from Belfast and told me that he had walked from Enniscorthy. I commented on the difficulty of getting lifts in these parts. He asked where I was going and said he would give me a lift to New Ross in his car. This was parked with a trailer attached a hundred yards up the road. Something had gone wrong and he walked into Enniscorthy for a coil. When he reached the car he discovered that it wasn’t the coil was at fault and he had had his walk for nothing. Furthermore, or better still, as they say in the North, he had paid two pounds for something he did not need. He was in the motor trade himself and had any amount of coils at home.

We were debating whether or not he should go back to Enniscorthy, return the coil and look for his money back, when a car pulled up and a plump little man that obviously knew the value of himself got out and came over to us.

He asked in a Belfast accent if he could do anything to help. In the tones of Stanley to Livingstone he said: ‘I saw the Northern number plate and thought I might help.’

My friend thanked him and introduced me as a Dublin chap he was giving a lift to. His fatness looked me up and down very coolly and said nothing. He took out cigarettes and offered one to his fellow-Lagonian, ignoring me completely. My friend declined and the fat one went off. The man of the good raincoat was very upset.

‘Did you see where he never offered you a cigarette? I would never have done that.’

I never encountered that sort of thing in the North itself. Except with a shipping clerk from Scotland. But then I was mostly amongst decent people in the Bluebell on Sandy Row14 and was seldom exposed to the extraordinary manners of solid men, North or South. In Anderson’s of Donaghadee the Nelsons or Fosters or any of the fishermen, Orangemen all, would die if they thought they had insulted you, even unintentionally.

‘No,’ said my friend thoughtfully, ‘he never offered you a cigarette.’ Then he shook his head and laughed. ‘Ah, well, I suppose it’s better to be mean than at a loss. And, by the same token, I think it wouldn’t be a bad idea if we went into Enniscorthy and got that two quid.’

In we went and he wasn’t long before he got his money back. The Enniscorthy man even seemed pleased to have a further opportunity for a discussion of trans-Border motor business.

For some reason we drove off to Wexford and the very first place we stopped the girl behind the counter was from Cushendun in the Glens of Antrim. They had no draught stout, but fat, squat bottles of a sort that my granny, God be good to her, used to call ‘dumpers’. After a few of them I sang ‘My Lagan Love’ and by the time we were leaving was working round to the ‘Sash’.

I parted from my Northern friend in New Ross on the steepest hill I’ve ever seen in a town. New Ross is a beautiful town like Chalon-sur-Saône or one of the towns around Lyon. Down at the Boat Club there is a diving board. I asked if I might use it and was given the use of a dressing room and all. I amused a little crowd on the bridge doing gammy dives off the top board. The club secretary told me the long boats cost five hundred nicker apiece. I could well believe the New Ross people have more where that came from. It seems prosperous and tidy.

In the pub I remarked on this to the man of the house, and also said it was a pity the river wasn’t used more. That they didn’t ship in their own coal, for instance.

‘Before you came up, I came in here with coal for Robinson of Glasgow,’ said a voice beside me in an accent as unlike south Wexford as my own. A little Dublin man on leave from a tanker and not long returned from Abadan, where he said the drink was dear and bad. His only comment on Persia. When he discovered I was a neighbour’s child, we talked about the hard chaws that we both knew on the North Wall and opposite. A doctor chap that came over from the Boat Club said it sounded ten times as bad as the Vieux Port in Marseilles.

‘Ah, not nowadays,’ said the little sailorman, ‘sure the young crowd coming up is no use for a decent heave. God be with the days you’d see the DMP15 being bet from one end of the quay to the other. With their own batons of a Saturday night. But now it’s like a graveyard. The young crowd is no good for anything except dancing and the pictures.’

‘Deed and it’s true for you,’ said a big man in a fine Cork accent, ‘they are not the great rackers their fathers were.’

The Irish Press, 28 September 1951

4

JOURNEY IN THE RAIN TO WATERFORD

A bakery van stopped in the wet night between New Ross and Waterford. I sat beside the man, and we began a conversation about the cost of living. Always a safe subject anywhere, any time.

He had eight children. Although my own economic problems are not nearly so numerous, I don’t like being bested. Like Lanna Machree’s dog, I’ll go a step of the road with anyone, and soon I was away ahead of him, describing the even greater difficulties of rearing a family in the capital. So great were my own troubles that she and I had parted. I just read my income tax assessment one morning, got up from the breakfast table, and walked out of the house. My only lodging since then, I said, with feeling, had been fields and haystacks.

‘And isn’t it a wonder a big able-bodied fellow like you would leave a poor woman high and dry with a houseful of little children?’