6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

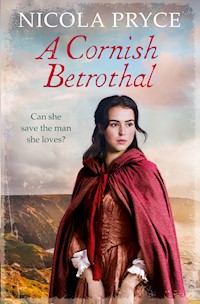

The fifth book in a sweeping historical romance series set in Cornwall, perfect for fans of Poldark Cornwall, 1798. Eighteen months have passed since Midshipman Edmund Melville was declared missing, presumed dead, and Amelia Carew has mended her heart and fallen in love with a young physician, Luke Bohenna. But, on her twenty-fifth birthday, Amelia suddenly receives a letter from Edmund announcing his imminent return. In a state of shock, devastated that she now loves Luke so passionately, she is torn between the two. When Edmund returns, it is clear that his time away has changed him - he wears scars both mental and physical. Amelia, however, is determined to nurse him back to health and honour his heroic actions in the Navy by renouncing Luke. But soon, Amelia begins to question what really happened to Edmund while he was missing. As the threads of truth slip through her fingers, she doesn't know who to turn to: Edmund, or Luke?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

NICOLA PRYCE trained as a nurse at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. She has always loved literature and completed an Open University degree in Humanities. She is a qualified adult literacy support volunteer and lives with her husband in the Blackdown Hills in Somerset. Together they sail the south coast of Cornwall, and the fact that she fell in love with a young Bart’s physician may well have influenced this story.

Also by Nicola Pryce

Pengelly’s Daughter

The Captain’s Girl

The Cornish Dressmaker

The Cornish Lady

Published in paperback in Great Britain in 2020 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Nicola Pryce 2020

The moral right of Nicola Pryce to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 090 3E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 091 0

Printed in Great Britain

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For my sister, Debbie Snelson,and our aunt, Dorothy Johnstone-Hogg

Family Tree

TRURO

TOWN HOUSE, HIGH CROSS

Dr Emerson Polgas

Physician, brother of Cordelia Carew

Seth Mortimer

Coachman

Bethany

Maid

PERREN PLACE, PYDAR STREET

Luke Bohenna

Physician

QUAYSIDE HOUSE

George Fox

Ship broker /Insurer /Importer

Elizabeth Fox

Philanthropist /Ship broker

QUAYSIDE

Margaret Oakley

Glovemaker

Sofia Oakley

Recently arrived from Portugal

Joe Oakley

Twelve-year-old boy

PENDOWRICK

Annie Alston

Housekeeper

PENDOWRICK RECTORY

Reverend Arthur Kemp

Mr Adam Kemp

FOSSE

POLCARROW

Sir James Polcarrow, MP

Landowner

Lady Rosehannon Polcarrow

Ardent campaigner for women’s education

Admiral Sir Alexander Pendarvis

Close friend and Amelia’s godfather

Lady Marie Pendarvis

Advocate for French prisoners

Come cheer up, my lads! ’tis to glory we steer,

To add something more to this wonderful year;

To honour we call you, not press you like slaves,

For who are so free as the sons of the waves?

CHORUS:

Heart of oak are our ships, heart of oak are our men;

We always are ready, steady, boys, steady!

We’ll fight and we’ll conquer again and again

‘Hearts of Oak’ by David Garrick

New Shoots

I no longer gaze at the top right-hand drawer of my mahogany dressing table. Six months have passed with Edmund’s letters left folded and unread, the blue ribbon tied in a neat bow. I will no longer read them: I do not need to. They are etched on my heart, some days burning so fiercely I can hardly breathe, other days filling me with a sadness that will never go away. Always they leave me with a glow of pride.

This letter, too, must join them: all of them wrapped in their silk pouch, no longer to be cried over.

From Admiral Sir Alexander Pendarvis

Office of the Admiralty and Marine Affairs

Whitehall, London

24th July 1796

My Dearest Goddaughter,

You have charged me with telling you the facts and so I will.

By all accounts, Midshipman Edmund Melville showed unparalleled bravery, distinguishing himself by his actions during the taking of Basse-Terre on Guadeloupe in April 1794. His unwavering courage helped erect the battery and proved the turning point in the capture of the island. His action was highly praised by Admiral Sir John Jervis and Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Grey; indeed, both men mention him in their dispatches.

Guadeloupe came under British sovereignty and Midshipman Edmund Melville resumed his duties aboard HMS Faith. However, yellow fever and dysentery took their toll on the garrison left holding the fort and by late April, only 13 officers and 174 men were left fit for service.

Guadeloupe is an island consisting of two very separate territories. Whereas the more mountainous western half was firmly under British control, the eastern side still contained pockets of French nationals determined to recapture the island. A contingent from the garrison was sent to quell these French nationals but their numbers were low, they were outnumbered, and before long found themselves besieged in Fort Fleur d’Epée.

As no reinforcements were at hand, General Grey gave the order to withdraw the men by sea and it was during the evacuation of the British soldiers that Edmund showed further outstanding courage in the face of peril. His complete disregard for personal safety, his unswerving loyalty to the men in his charge, indeed his absolute determination to go back for the wounded, saved the lives of at least forty men. There is no doubt that he gave his life so that others might live.

My dearest Amelia, in my capacity of Agent to The Transport Board, I have pursued every possible avenue open to me. The representative I sent to Guadeloupe has assured me he left no stone unturned, though I wish it were otherwise. Two British prisoners were captured on that day, and both subsequently died of their wounds. We have their names and Edmund’s was not one of them. I can tell you with absolute certainty that Midshipman Edmund Melville is not listed in the prison records of Fort Fleur d’Epée on that day, nor in the weeks and months that followed.

Less than a month after Midshipman Edmund Melville showed such bravery, French forces led by Victor Hughes counter-attacked and secured the eastern half of the island. They took Fort Fleur d’Epée and it is there that our prisoners were held. Lieutenant Melville was not one of them.

Seven men went missing from HMS Faith that day and seven British sailors were confirmed buried. The Fort records are very clear and the numbers tally; one officer, and six sailors. The log sent the following day by Captain Owen states Midshipman Edmund Melville as missing, presumed dead, and I must urge you to take heart from the words written alongside – a truly brave man, deserving of the highest honour.

My dearest Amelia, though it grieves me to speak so plainly, the fighting Edmund encountered was fierce. Two soldiers saw him fall; one was too injured, the other went back to help him but was captured and died later in the fort. Edmund was thrown forward by the force of the cannon and immediately lay lifeless. He did not stir and to this day they believe Edmund Melville died instantly. As a direct result of his brave action, the evacuation was successful. Twenty soldiers were picked up from the water, and another twenty rowed to safety.

What we must conclude from my investigations is that Edmund is at peace, my dearest, and from the depth of my heart I urge you to let him rest. As one who loves you like a father, I urge you to seek your own peace and find new happiness.

Your Devoted Godfather,Alexander Pendarvis

I was so sure I could never love again. So sure. But nature knows best, sending out her fragile new shoots from what seems like barren wasteland.

Be watchful for the emergence of new shoots and protect them against the first sign of frost.

THE LADY HERBALIST

Chapter One

Town House, TruroSaturday 30th December 1797, 2 p.m.

‘There . . . no, a bit higher. Let me fasten it again.’ Bethany’s hands trembled as she re-pinned my brooch. ‘I’m all fingers and thumbs. Honest, it’s like I’ve never done this before.’

Her eyes caught mine in the mirror. I was wearing my new apricot silk, high-waisted and edged with lace, my hair loosely coiled and threaded with pearls. I looked flushed, almost giddy, my eyes shining like an excited child. She stood back, clasping her hands, and I shook my head at the glittering diamonds. ‘No . . . perhaps not.’

She nodded, her smile turning conspiratorial. ‘Well, it is ye birthday and ye might very well be given a present of some jewellery . . .’ She put Uncle Alex’s brooch back into its silk-lined box, pursing her lips. ‘You may be given a necklace, or maybe a ring?’

‘Bethany!’

The clock on the mantelpiece chimed two and Bethany ran to the window, peering down with the same jumpy excitement. The pursed lips were back, the terrible attempt to hide her smile. ‘Oh, goodness, he’s come early. Perhaps it’s on account of seeing to Lady Clarissa’s ankle . . . or perhaps he wants a quiet word with Lord Carew? Perhaps he’s got something of great importance to ask?’

I joined her at the large sash window, my cheeks flushing. She was worse than Mother – they all were: the maids running up and down the sweeping staircase, singing as they dusted, the footmen smiling as they polished the silver. ‘It’s only a small birthday gathering,’ I whispered, trying not to look too eager.

The day was overcast, a thick blanket of clouds sitting heavily above the town. Men stood hunched against the biting wind, the corner of High Cross almost deserted. Luke was right on time, dressed in his heavy overcoat, his collar pulled up, his hat drawn low over his ears, and I thought my heart would burst. He was smiling up at me, that loving smile that made my whole body flood with warmth.

‘Yer mother’s foot’s done very well under Dr Bohenna’s attentive care. His daily visits have made all the difference.’ Bethany was as flushed as I was, and well she might be, all of them thinking I had fallen for their ruse. ‘I do believe Lady Clarissa will soon be up and able to walk on her broken ankle.’

Luke had not yet knocked on the door and stood smiling up at my window. I leaned against the pane and smiled back. ‘I take it Papa has had no more of those dizzy turns?’

‘None that I know of . . .’

‘And Cook’s headaches have stopped . . . and Seth’s indigestion is better?’

Bethany had the grace to giggle. ‘All better. All thanks to Dr Bohenna.’

The footman must have opened the door because Luke picked up his heavy leather case and disappeared under the pillared portico. Across the square, the stones of St Mary’s church were growing increasingly grey, the spire now swallowed by the darkening sky.

Our house was set away from the main commerce of the town, one of the few houses to have its own stabling and coach house. Built thirty years ago, Mother had named it ‘Town House’ mainly as a penance. Must we go to the Town House? was her frequent lament. Our country estate, Trenwyn House, was only five miles downriver, but we wintered in Truro like most of society. Neither my farmer father nor my mother – a freethinking believer in Nature – liked the protocol and gossip of town. Society can be very trying, was another frequent saying of theirs and usually I agreed. But not this year. This year had been different. This year I had danced at balls and laughed at plays; I had dressed in my best gowns and attended all the concerts.

‘That’s a north wind,’ I said. ‘Those clouds look as if they might bring snow.’

The trees by the church stood bare of leaves, the tips of the branches rustling in the wind. People were hurrying from the market, men pushing barrels or staggering under furze packs; women were carrying heavy baskets, clutching their woollen shawls tightly to their chests. It had snowed before on my birthday, a fine dusting of white powder covering the vast heaps of coal on the quayside and thin layers of ice on the decks of the ships. Perhaps it would snow today, too.

I turned back to the warmth of my bedroom. All the fires in the house were blazing, every room filled with warmth and laughter. I caught a glance in the mirror and hardly recognized myself – I looked like a giddy girl of seventeen, not a mature woman of twenty-five.

Bethany wiped a tear from her eye, her plump cheeks the colour of plums. ‘Miss Amelia, ye must know what’s meant is meant?’

I smiled at her, warmed by the love in her eyes. Her blush deepened to a fiery red. ‘I’ll bring your shawl down for ye. Ye might need it . . .’

I flew down the stairs as if I had wings. As a child, Frederick had taught me to slide down the banisters and I had taught each of my nephews in turn. A useful skill, I had assured them, like climbing trees and making bows and arrows from saplings; like rowing and fishing and cooking marshmallows round an open fire. Like rising with the dawn to gather dew-covered herbs, catching the first call of the songbirds, the air so fresh it cut you to breathe.

The marble floor was gleaming, the mahogany front door polished to a shine. A large parcel rested on the hall table, a footman trying to hide it from my view. The door to my father’s study was ajar, the sounds from within too hard to resist, and I peeped into the room. Papa and Luke were standing with their backs to the roaring fire; both were laughing, Father with a glass of brandy in his hands.

‘Amelia, dear child, come in.’ He coughed, smiling at Luke. ‘No need to tell your mother about this.’ He held up his glass, finishing it swiftly. ‘Doctor’s orders, nothing more.’

Luke bowed formally, his eyes setting me alight. He always dressed smartly, always with the same professional decorum, and I loved him all the more for that. His dark jacket and breeches were good quality, his boots polished and shining; never any silver buckles, just a white cravat, neatly folded and pinned with an enamel pin.

‘Happy Birthday, Amelia,’ he said, and my heart leapt even higher.

There was a time when his smile had been tentative, when he had been too scared to look me in the eye, always glancing down, his natural good manners and shyness at once endearing. But not now. Now, the love in his eyes sent ripples racing through my body: the love of true friendship and complete trust.

‘Is that large parcel in the hall from you, Luke?’

He smiled, shaking his head. ‘I’m afraid not. My present’s in my pocket. Actually, I have two presents for you – and both are in my pocket.’

‘Indeed, and what a present it is.’ Papa put down his glass. He was wearing his adored red felt cap and woollen housecoat, his strong farmer’s frame tied like a parcel in gold braid. ‘If you’ll excuse me, my dears, I’ll be in trouble if I don’t get changed. I believe our guests are to arrive any moment.’

We followed Papa to the door, watching him cross the hall and mount the stairs. Luke reached for my hands, pulling me back out of view of the footman. I knew he would. I had been anticipating this stolen moment all morning. He held my hands to his lips. ‘You look beautiful, Amelia.’ He covered my palm with kisses. ‘I’m sorry, I missed that bit . . . I’ll just have to start again. Happy Birthday, dearest, dearest Amelia.’

Footsteps hurried across the hall, last-minute instructions echoing up the stairs, and I leaned against Luke’s strong chest, his arms closing round me. His lips brushed my hair.

‘Who did they send you for this time? We haven’t had illness in our house for years, and suddenly we’re falling like a pack of cards! Mother’s quite outrageous.’

‘And my mother. They’re in league and thank goodness they are. I think they’re scared that if they didn’t summon me I’d catch my death of cold standing outside, just hoping for a glimpse of you.’

‘Except Mother’s foot – that’s real. I saw her fall and how painful it was.’

His arms tightened. ‘It’s mending well. I’ve forbidden her from climbing any more ladders. Do you think she’ll take my advice?’

‘Mother, do what she’s told? The idea’s preposterous.’

He laughed the soft laugh I loved so well. ‘Amelia, now we’re alone . . . while I have you to myself . . .’ He released his hold, looking deep into my eyes. He seemed hesitant, as if gathering his courage. ‘Your father’s been extremely kind, he’s given me every encouragement . . . both Lord Carew and Lady Clarissa have.’ He knelt down, reaching into his jacket and my heart began thumping, jumping, racing so hard I could hardly breathe. In his hands he clasped a smooth walnut box.

His bluest eyes searched mine, full of tenderness and understanding. Deep furrows etched his forehead, eight long years of studying and his patients’ suffering leaving their mark. His brown hair was worn short, receding slightly at the temples, his chin was freshly shaven. His cheeks were flushed, a slight tremble in his hand. He was not smiling but looked suddenly nervous. How I loved him. How I adored him.

A sound of scuffling was followed by a breathless shout. ‘Aunt Amelia . . . Aunt Amelia . . . Oh, here you are – we’ve been looking all over for you.’ My two young nephews beamed with pleasure, their faces flushed from the cold. Their smiles widened. ‘Oh, gosh. Good afternoon, Dr Bohenna, I didn’t see you down there. Have you dropped something? Only we can help you look for it. We’re good at finding things.’

Luke smiled at me, getting up from his knees. ‘No, nothing’s lost.’ Our eyes locked and I wanted to throw myself in his arms.

William and Henry embraced me in turn. ‘Happy Birthday, Aunt Amelia . . . we can’t wait to give you our present. Are you coming? Everyone’s waiting for you in the drawing room.’ They slipped their arms around my waist, both growing so fast they almost reached my elbows. ‘There’s a simply enormous present from Captain de la Croix in the hall. What d’you think it could be?’

Mother sat on the chaise longue, her bandaged ankle resting on a cushion. Jewels glinted in her green turban, a host of dark eyes bobbing in the feathers above her. Her oriental green gown was threaded with gold, her embroidered shawl sparkling with exotic animals. Papa had somehow been persuaded to swap his favourite corduroy waistcoat for embroidered silk, his felt hat begrudgingly replaced by his grey wig. His smile grew mischievous as he handed Mary Lilly a glass of punch.

‘I hope this isn’t as strong as your Christmas punch, Lord Carew?’ Mary Lilly smiled up at him, her soft Irish lilt full of reproach. She had the same blue eyes as Luke, the same tender smile, and the soft lines on her face showed the same gentle compassion. Her white hair was tied back in a loose bun, her velvet hat matching her blue, silk gown. Dearest Mary, with her plain speaking and her inordinate good judgement, had become Mother’s closest friend: they sat on several charity commissions together and were a formidable force for women’s education. I loved everything about her.

‘Mr Lilly sends his apologies. He’d like to be here, but . . . well, you know how his work takes him away.’

I smiled back, unable to answer. I was being dragged across the room by William and Henry. My sister-in-law held out her arm, embracing me warmly. ‘Have we surprised you?’ She held the youngest of my nephews in her other arm and he squealed loudly as we embraced.

‘You have, Cordelia – a complete surprise. It’s so lovely to see you. How’s my little Emmy?’ I covered the beaming child with kisses. ‘Are you staying in Truro? I can’t believe you’re here.’

Cordelia pulled Emmy back to save my gown from soggy gingerbread. ‘The boys wanted to give you their present, and we’ve such wonderful news. My brother Emerson’s coming home . . . it’s unexpected and really very wonderful.’ She wiped away a tear. ‘He’s expected any day now. I’ve brought the children to stay with Mama so we can be here when he arrives.’

My three nephews were smiling, Henry twisting his hands against his chest. ‘We haven’t met Uncle Emerson yet. He’s been away for so long.’

‘Indeed he has, Henry.’

So much love, so much happiness. I glanced at Luke and my heart burned. Behind me, I heard the footman cough politely. ‘Mrs Elizabeth Fox.’

‘Elizabeth!’ I rushed to greet my dearest friend. ‘I can’t believe you’re here as well. What a wonderful birthday this is turning out to be.’

Elizabeth stood smiling from under her soft white bonnet. A member of the Society of Friends, she often visited her house in Truro, though their family home and shipping business were in Falmouth. Her cheeks dimpled, her rosebud lips pursing in mock horror. ‘As if I wouldn’t come on your birthday! Wild horses couldn’t drag me away.’ Her soft grey gown rustled as I led her to the fire, her simple white collar accentuating her flushed cheeks. She rubbed her hands together, gleefully accepting a large glass of lemonade. ‘That wind’s from the north – I think it’s cold enough to bring snow.’

Chapter Two

I untied the ribbon on the boys’ present. ‘It’s so we know whether we can come in or not.’ William pointed to the piece of wood. ‘We found it on the shore and scrubbed it really hard. Then we polished it.’ He held it up. ‘Henry painted this side . . . Aunt Amelia is busy . . .’ He turned the sign over. ‘And I did this side because there’s an extra word . . . Aunt Amelia is not busy. It’s for your painting studio.’

I kissed them both. ‘Thank you. It’s beautiful and very useful. Your lettering’s very neat. Thank you so much, I shall use it from now on.’

The boys ran to the table. ‘Now shall you open this big present from Captain de la Croix?’

‘I wonder what it can be.’

Two years ago Captain Pierre de la Croix had given Frederick his parole after HMS Circe captured his ship. He had stayed with us in Trenwyn House while Frederick sorted out his parole papers and we had attempted to teach him cricket – to no avail. He was now in Bodmin with several hundred other French officers and we kept in touch. He was charming, his perfect manners endearing him to everyone. Papa reached for his scissors and I read the attached note aloud.

Dear Miss Carew,

A small gift that cannot in any way repay your kindness or your family’s generosity to me. It is not yet complete, but I wanted you to have it for your birthday. Do not set sail quite yet – I have eight more pairs of animals to finish.

My regards to all your family.

I remain, your humble servant, Pierre de la Croix

I unfolded the brown paper. ‘An ark!’ I was lost for words. ‘He’s made me an ark.’

Every plank on the deck was individually crafted, each a slightly different shade, and we gathered round the intricate model, marvelling at the inlaid wood. The hull was round-bellied, sweeping in a delicate curve, with swirls of mother-of-pearl glistening on the bow. ‘Look – it’s like waves frothing against the side.’

Each exquisite detail drew cries of disbelief. Portholes gave glimpses of animals in individual stables, windows in the cabins showed figurines on chairs. I opened the side door and pulled down the gangplank. ‘Look, an elephant . . . a tiger.’ Horses followed, then gazelles and sheep and cows, everything carved in the finest detail. ‘He must have whittled these . . . and engraved these from bone.’

Papa held up a gleaming white horse. ‘And polished them. It must have taken him a very long time. Still, I suppose he has the time. There’s a growing market for these French fancies – they command a good price. Prisoners’ work is being commissioned by many in London. But this is quite the most splendid of everything I’ve seen.’

Elizabeth shook her head in wonder. ‘How is he? Does his note say if he’s well?’

‘No, but we’ve only just seen him. Mother and I took him a hamper for Christmas. He has very comfortable lodgings in Bodmin – the proprietor, Mrs Hambley, spoils him quite terribly.’

Elizabeth must be in Truro for shipping business, not just for my birthday. She held up a giraffe. ‘I understand the prisoners sell their trinkets in the market – I gather some of them teach fencing and dancing. The people of Bodmin must be getting quite used to having French officers on their streets.’

Papa shrugged his broad shoulders. ‘I can’t see it as a problem – so long as there’s enough food for everyone. Bodmin’s in a rich vale – it’s not a poor town, and I think that makes all the difference. Here, let me.’ He placed the ark on the floor for the boys to examine.

‘Well, my present’s going to seem very dull in comparison to Captain de la Croix’s.’ Elizabeth smiled, handing me a parcel. I slipped off the ribbons and held up a pair of soft leather gloves. ‘For your herb garden,’ she whispered as I reached to kiss her. ‘They’re to replace your old ones. Try not to get holes in these ones quite so soon.’

Our glasses duly refreshed, and the fire newly stoked, Mary Lilly smiled. ‘My present’s from London. I do hope they’re what you’re looking for, only I know you need finer tipped brushes for your herb paintings and such.’

I unrolled five finely pointed paintbrushes. ‘Oh, Mary, they’re perfect. They’ll make all the difference. Thank you so much . . . where did you find them?’

Her eyes crinkled along their loving lines. ‘I had them made for you, my dear. I said to make them as fine as an eyelash – the proof will be in the painting, but I’m thrilled you like them.’

Liked them? I loved them. They were absolutely perfect. Painting was my passion, especially my herbs. Sometimes the shading in my flowers was too heavy, the veins in the leaves too thick. Often I needed just the illusion of colour, a nuance, the faintest blush.

I had to look away. I remembered another birthday, another gathering of families around the fire. Yet we had not been smiling; we had stared into the flames in stunned silence. The pain was passing now, allowing me to breathe.

Edmund would have wanted this: he would have wanted me to be happy.

Mother ducked expertly as Young Emerson reached up to catch her feathers, handing him some gingerbread instead to feed the animals. He staggered across the carpet to join the others and she swung her foot off the cushion, patting the chaise longue beside her. ‘Our present cannot be wrapped, my dear. We’ve decided to build you a new walled garden – next to the gatehouse at Trenwyn.’

Papa’s smile broadened. ‘So you can distribute your herbs without everyone marching across our lawns.’

‘Not that we don’t like your visiting apothecaries and physicians, my dear.’ Mother glanced at Luke, smiling her most endearing smile. ‘Of course we do . . . it’s just . . . Well, your father thinks they mess up the gravel.’

‘Very tedious. No sooner the stones are raked back, another horse and cart comes tearing up the drive. Endless stones scattering everywhere.’

‘And sometimes, we’re not dressed for company. Your visitors seem rather shocked to see me rowing on the river – or fishing.’ She winked at her adoring grandsons. ‘And sometimes they get shot with bows and arrows, don’t they, boys?’

‘Shot and held prisoner, Grandma.’

‘Indeed. Though we do let them down eventually.’

Despite the heat from the fire, Cordelia’s cheeks went ashen. What Mother knew would strengthen, Cordelia believed would weaken. Far better to keep Cordelia in the dark. ‘Down?’ she whispered.

Mother shrugged. ‘From the treehouse. Oh, don’t look like that, my dear – it’s not that high. Most of them survive.’

I hugged Papa. Another walled garden and my output could double. My herbs were already distributed all over Cornwall, but demand was outgrowing supply. Now I could fulfil all my orders and my promise to supply the new infirmary.

Papa’s bear grip tightened. ‘You can draw up your exact requirements, my dear – any shape and size you require and as many new gardeners as you need. We’ll start building it in the spring.’

Luke had his back to the fire, the love in his eyes making my heart soar like a bird. Dearest Luke, with his shy smile and his sense of honour, his integrity, his complete understanding. His determination to stand back while I grieved, never demanding anything from me. Always professional, always asking my opinion; discussing tinctures and balms, giving me lists of the herbs he needed, asking whether I could suggest others. He had unlocked my heart so completely, and now it was his forever.

His eyes on my eyes, his hand reached into his pocket. ‘That only leaves my present.’ His voice was almost a whisper, the room growing quiet around us. I would say yes, yes, yes. A thousand times, yes. Outside, the sky was darkening and the shutters would soon be closed; we would draw round the fire and play blind man’s buff. My twenty-fifth birthday; the start of my wonderful new life.

It was a letter he drew out, not the small walnut box. He held it in his hand, his eyes burning mine. ‘My birthday present is on its way, or rather, I should say on his way. This letter is from Mr Burrows of Burrows and Son, the renowned London publishers of botanical prints. Amelia . . . I rescued one of the prints you’d discarded – it wasn’t up to your standard but to me it looked perfect.’ He shrugged his shoulders. ‘And it must have looked perfect to Mr Burrows, too.’

He unfolded the letter. ‘I shall be venturing down to Somerset and Devon late January and will call on you in early February. I believe Miss Carew has great talent and if this is a discarded painting, then I certainly look forward to seeing her entire collection with a view to publication.’

Tears filled my eyes. ‘But, Luke . . .’

‘You’re not cross with me, are you? Only I knew if I asked, you’d refuse.’

Such a renowned publisher coming to see my drawings? I was almost too shocked to speak. ‘But, Luke . . . he might not want them . . . they might not be good enough. I’m not ready for them to be seen.’

‘You told me you’d nearly finished. That you’d written everything you needed—’

‘Yes, I have. I just need to add a few more tinctures – maybe some general health advice from your father’s herbal . . . but to have it published? That’s too much to hope.’

‘Why not let Mr Burrows be the judge?’

‘The man will be a dammed fool if he doesn’t take them all. Dammed fool. Dammed fine present.’ Papa picked Emerson up, throwing him in the air, tickling him as he caught him. ‘So, you’re to have a famous aunt, are you? What shall we call this book of yours, Amelia?’

Luke handed me the letter. ‘That’s for Amelia to decide, but my suggestion would be The Lady Herbalist.’ His voice dropped. ‘And I think it should be dedicated to Midshipman Sir Edmund Melville.’

The pain flooded back. Every plant planted, every painting painted; every early morning and every wakeful night spent thinking of Edmund. Luke’s generosity of spirit was more than I could bear – to enable me to honour Edmund was the kindness present of all.

Loud knocks echoed from the front door, footsteps hurrying across the hall.

‘Is someone else coming to surprise me?’ I asked, blinking back my tears.

Mother glanced at Mary. ‘Mr Lilly, perhaps?’

Mary shook her head. ‘I don’t believe so. He’s away for another week.’

I could hear muffled voices, then the doorman entered, bowing, crossing the room with a letter on his silver tray. ‘A letter, m’lady. Straight off the Falmouth Packet.’

Mother’s back straightened, her smile vanished. She took a deep breath. Every express brought terror, every letter hurried across the hall bringing the same the same stab of dread. Three sons in the navy, three sons held lovingly in her thoughts every moment of every day. I watched her mouth tighten. ‘The poor man must be frozen. Have you offered him some refreshments?’

‘Indeed, m’lady. He’s been shown down to the kitchen.’

All colour had drained from Mother’s face. She looked older, her cheeks ashen. She could hardly hold the letter. ‘But it’s not for me . . . it’s for—’

She glanced in my direction and the room began to spin.

Chapter Three

Their faces were a distant blur. I could not breathe. ‘Some brandy, my dear?’

I shook my head at Papa’s proffered glass. It’s not his writing. Not his writing.

Mother’s grip was strong and comforting. ‘It’s from Portugal,’ she said, ‘but it seems to have been everywhere – there are so many scribbled directions, I’m surprised it’s reached you at all.’

Elizabeth must have helped me to the chaise longue, Cordelia must have gathered up the boys and ushered them quickly through the door. The sudden silence was unnerving, just the thumping of my heart and my head swimming. I looked for Luke. He was facing the fireplace, standing with straight shoulders and a stiff back. Mary Lilly reached for a chair and sat down, staring at her clasped hands.

The writing was faded and almost impossible to read. It was well formed, but it was not his writing. The paper was worn, torn at the edges, a crease across the middle, half-obscuring my name. The wax was sealed with a cross inside a heart. ‘Shall I open it?’ whispered Mother.

‘No. I’ll open it.’

I slipped the seal and fought to breathe. It was his writing, his dearest, dearest writing. I felt giddy, faint, the blood rushing from my head. It was four years since the news of his loss, eighteen months since the confirmation of his death. I had given up all hope. The letter shook in my hands.

‘He’s alive . . . his writing’s very shaky . . . but then it stops. It just stops and another hand takes over. I can’t read it – it’s in a language I don’t understand.’

Elizabeth’s arm closed round me. ‘Would you prefer to keep your letter private?’

Tears streamed down my cheeks. ‘I can’t make sense of it.’

She took the letter. ‘He’s in The Convert of the Sacred Heart, São Luís, Brazil. To Miss Amelia Carew, Town House Truro. August 4th 1796.’ She stopped. ‘But that’s . . . almost eighteen months ago.’

My heart seized. ‘Oh no . . . I didn’t see that.’

She cleared her throat. ‘The writing’s very shaky – it’s very hard to read. It says . . . My beloved Amelia, I’m well, thank the Lord, though this is the first day I’ve been allowed out of bed to write. I’ve been given half an hour, and then I shall be placed back in bed by the good nuns who have saved my life. Only half an hour to tell you everything. Yellow fever has me in its grip, such that I can hardly hold the pen, but I will be strong again soon and I will search out the swiftest ship—’

Elizabeth looked up. ‘That’s where he stops. The rest of the letter is written in a different hand.’ She turned the page. ‘There’s nothing else in Edmund’s writing – it looks like Spanish . . . no, I suppose if it’s Brazil, it’s probably Portuguese?’

Papa took the letter. ‘Who reads Portuguese round here? Elizabeth, have you any ships in from Portugal? In Falmouth we’d find any number of Portuguese speakers, but here, in Truro . . . in January?’ He turned to Mother. ‘I might have to go to Falmouth to get it read.’

I fought to breathe. I was in a lime-washed room, a huge wooden cross hanging above me. The floor was polished red tiles, a fierce sun slanting through the grilles of the window. They were helping him from an iron bed, gently positioning him at a simple wooden table. Edmund was grasping the pen, trying to stop his hands from shaking. My beloved Edmund, half delirious with fever, reaching for a pen to tell me he was alive.

Every emotion I had tried to bury was flooding back – his smile, the shake of his black curls. His hand slipping into mine – the boy from my childhood who had stolen my heart, the not-so-shy youth who stole kisses as we gathered in the hay. The day he asked me to marry him, standing on the shore of the river below Trenwyn House, kissing the entwined grass ring so tenderly before placing it on my finger. The man I adored, telling me he was still alive. The man I had vowed to love until death did us part.

I could hear Mother calling for the globe. My brothers’ latest whereabouts were chartered with silver pins, Edmund’s last battle marked by a black pin on the distant shores of Guadeloupe. Papa placed it in front of us and Mother spun it round, putting her finger straight on the tiny island.

‘Brazil’s not directly south . . . it’s here . . . a long way southwest of Guadeloupe. Heaven knows how many miles away.’

Elizabeth traced the outline of Brazil. ‘It’s a vast coastline. São Luís isn’t marked on here, but I believe it is in the north . . . somewhere in this region. Trade with São Luís is a growing business – we’ve insured several ships from there. Cotton growers, mainly the Maranha Shipping Company. They ship their cotton to London and Liverpool – some of their ships come to Bristol. We cover the trade to Falmouth.’

Luke walked stiffly from the fireplace and knelt by my side. He looked pale, his fingers loosening his white cravat. ‘I’ve heard Portuguese spoken in the seaman’s hostel behind the quay. Someone there might read Portuguese – I’ll leave you now and search the quays.’

‘His writing just stopped. Luke . . . he was so frail . . .’ The words caught in my throat. ‘What if he . . . ?’

He handed me his starched white handkerchief. ‘We don’t know that, Amelia.’

‘He was in the middle of a sentence.’

‘We must get the letter translated. I’ll search the quays. If I’m not successful, your father and I will go to Falmouth.’

He did not take my hand but bowed formally. Any other time, he would have taken my hand and put it to his lips. He would have turned at the door and smiled and I would have gazed back at him. ‘Lord Carew, Lady Clarissa, I’ll take my leave.’

A thousand knives thrust deep into my heart. I was losing Edmund all over again, the old wounds opening up, the pain so raw I wanted to cry. I should never have stopped believing he was alive. I had abandoned him. I had given up hope when I should have stayed strong.

‘Amelia?’ Elizabeth’s voice drifted through the pain. ‘The lady I bought your gloves from had her daughter-in-law with her – she was helping in the shop. You know the leather shop on the quay?’

‘Yes,’ I managed to murmur.

‘I’m sure Mrs Oakley said she had come from Lisbon. She certainly looked Portuguese.’ Her heart-shaped smile was not lost on Mother. ‘Lady Clarissa, might Amelia and I take a walk to the quayside?’

Papa stood to attention. ‘I’ll accompany you, my dears. I’ve been cooped up all day and need to stretch my legs.’ His frown deepened as he glanced at the letter. ‘It’s taken eighteen months to reach here – eighteen months.’

The cold stung my cheeks and I drew my fur-lined hood over my bonnet, linking arms with Elizabeth, our hands thrust deep into our muffs. The streets looked gloomy in the fading light; lamps were being lit, everyone bending their heads against the wind that funnelled down the cobbles. The market square was deserted, the street sellers packing away their trolleys. Papa strode purposefully in front of us, giving a coin to each ragged child he saw picking through the discarded vegetables strewn on the pavement.

Women were gathering hay blowing from the stables, their heads wrapped in thick woollen shawls. Voices rose from the inns, men stretching out their hands in front of burning fires. Papa’s boots thudded in front of us and we walked in silence, the masts of the ships now looming above us. We turned the bend, entering Quay Street, and I caught the familiar smell of rotting mud at low tide.

Quay Street was the beating heart of Truro; it was where my friend Angelica Trevelyan lived, where Robert and Elizabeth Fox had a branch of their shipping business. It was where the Welsh Fleet brought coal in for the mines and shipped tin out to the smelters; tin, copper, smelted iron – the black blood that flowed through the city. He had survived that day; he had crawled from under the gunfire. He had escaped from the island.

A lamp burned in Mrs Oakley’s shop, lighting up the polished wooden counter and the glass-fronted cupboard behind it. Two women were sitting stitching in the lamp’s glow, their heads bent; one had grey streaks and wore a white mobcap, the other had thick black hair coiled neatly under a ruby-red bonnet.

‘There,’ whispered Elizabeth, peering through the tiny leaded panes. ‘I’m not wrong, am I? She does look Portuguese.’ Like all the Society of Friends, Elizabeth’s grey woollen cloak was lined in black satin. She wore no jewellery, no coloured silks, no lace or ribbons, nor did she need to; her beauty shone from within, her kindness and compassion matched only by her extraordinary intellect.

The door opened to the sound of the jangling bell and both women looked up. A flash of anxiety crossed Mrs Oakley’s eyes and I withdrew my hands from my muff, showing her how well my new gloves fitted. They curtseyed deeply, Mrs Oakley with a twinge of pain, the younger lady with an air of sadness. ‘They fit perfectly,’ I assured them. ‘Quite the loveliest gloves I have.’

They seemed to curtsey deeper and longer than usual, not daring to glance at Papa, who filled their shop with his great coat and fur hat. Most wives ushered their husbands next door to where Mr Oakley sewed saddle bags and travel cases.

‘What an honour, Miss Carew, Lord Carew . . . Mrs Fox.’

The younger woman seemed rather fragile, her skin sallow beneath a crown of jet-black hair, a look of suffering in her dark eyes. Her gown was good quality silk but fraying at the hem, the lace at her sleeves greying. By her glance, I instantly thought her to be a woman who knew sorrow; someone who would understand if I cried in front of her.

Elizabeth smiled. ‘Mrs Oakley, I remember you saying your daughter-in-law has recently arrived from Lisbon. May I ask if she can read? Only Miss Carew has a letter of great delicacy that we believe to be in Portuguese.’

She had addressed the elder Mrs Oakley, but the younger woman nodded, her chin rising slightly. ‘I am Portuguese. I am educated, and I will gladly read your letter.’ Her voice was throaty, thickly accented, but her English was perfect. She did not smile, but held out her hand, taking the letter to the glow of the lamplight. From the corner of the room, the dark eyes of a child stared back at me. He looked poorly nourished with shadows under his eyes, his thin wrists protruding from beneath the sleeves of a fraying jacket.

I gripped Elizabeth’s hand. I would not cry. Somehow, at some time, I would visit Edmund’s grave in the Convent of the Sacred Heart, and bring back the cross that had hung above him. I would take it to his family seat and lay it next to his father, Sir Richard Melville, fifth baron of Pendowrick Hall. I would collect some earth from his grave and carry it home in a casket.

Elizabeth’s hand tightened round mine. The young woman was taking her time, reading the letter carefully. She had extraordinarily high cheekbones, blood-red lips and heavy black brows. She was beautiful; mournful, but beautiful.

‘The letter is finished by one of the nuns. Miss Carew, may I suggest you sit down?’ She waited while Mrs Oakley drew up a chair for me. ‘The man writing the letter did not die . . . he was forcibly taken by Portuguese sailors. Irmã Marie says the Convento do Sagrado Coração de Jesus is frequently raided by ships searching for crew. Their convent is situated close to a beach and ships often anchor there in the sheltered water. The sailors row ashore and capture any man they can find. She says she watched them drag Senhor Melville across the sand and throw him into their boat together with the provisions they had plundered. She says they are powerless to stop them – they can only barricade themselves into a locked room and pray the lock holds.’

The room was spinning. I heard the faint jangle of a bell, felt a blast of icy air. Luke stood in his heavy overcoat. ‘Oh, I see you’ve got here first . . . I’ve just been told a lady in this shop speaks Portuguese. Amelia, are you all right? Lord Carew, please, allow me . . .’

I felt myself lifted in strong arms, heard the distant babble of concerned voices. I could say nothing, do nothing. I was falling – spiralling downwards, a deep, black void opening beneath me.

Chapter Four

Mother limped across the bedroom, leaning heavily on Bethany’s arm. She settled next to me with a wince of pain. ‘Good, you have a little more colour. Are you feeling any better?’ She lifted my chin and frowned. ‘No, I can see you’re not. I think we’ll use the draught Dr Bohenna prescribed. Bethany, be a dear and run and get it.’

Bethany curtseyed, her eyes wide with fright. I was never ill, I never fainted; I was in a daze, that was all. Four years of imagining how I would fly round the house with wings, how I would laugh and sing, dance with Bethany until we were giddy. Eighteen months ago, Edmund had been alive. But he was weak. He had barely been able to leave his bed.

For the first time in my life, I did not want Mother to sit on my bed. I did not want to hear the slight censure in her tone, or watch the fleeting disapproval in her glance, the tightening of her mouth at the thought of Edmund and his haste to join the navy. She reached for my hand and felt for the pulse racing at my wrist. ‘Your father says the convoys leave the West Indies before the hurricane months of August and September, and Elizabeth says the insurance rates double after July; therefore, we believe the ship must have sailed south. Journeys on merchant ships can take a year . . . eighteen months . . . even two years.’

Sobs caught my throat. ‘He was so weak.’ Mother folded her arms round me, the scent of rose water and lemon lanolin taking me back to my childhood. ‘I should have waited longer. I should never have deserted him. I’ve been dancing at balls . . . laughing . . . singing, and all this time Edmund has been suffering.’ I felt as cold as ice.

She tucked away a tear-soaked curl. ‘Luke’s prescribed you a draught, my dearest.’

Bethany’s red-rimmed eyes avoided mine. She must have seen me shiver because she added another log to the already blazing fire. Pulling the eiderdown round me, Mother handed me a glass of amber liquid. ‘Drink this, my dear. Would you like Bethany to sleep in your room?’

I shook my head, sipping the fiery liquid.

‘In that case, we’ll leave the bell by your bed. Ring it the moment you want company.’

She spoke softly, kissing my forehead, but I knew what she was thinking. He should have discussed joining the navy before he left. Mother would never forgive Edmund for that, and Frederick would never forgive him for not sending me a keepsake – a token, or a miniature portrait for me to remember him by.

Mother was about to snuff out the candle. ‘Let it burn,’ I whispered.

She knew my intention full well. ‘No, my love, I insist you sleep.’ Her abundant grey hair fell about her shoulders, her richly embroidered shawl the work of my hands. Always a red flannel nightdress in winter, a white cotton and lace one in summer. Her bejewelled Chinese slipper sparkled in the candlelight, the bandage on her ankle white against the red nightdress. The colour of blood. Edmund must have crawled away under the cannon fire. He would have been badly injured. He would have been so weak.

‘Lady Melville and Constance must be told,’ I whispered. ‘I must go to them.’

‘Hush now . . . try to sleep. Sofia Oakley has kindly offered to write out a translation. She’s coming first thing tomorrow and we can send them a copy.’

Bethany helped Mother back to her room and I waited for them to think I was asleep. A red glow flickered in the fireplace and I slipped silently from my bed, opening the top right-hand drawer of my dressing table. The silk pouch felt painfully familiar and I knelt by the fire, taking out his first letter. I knew it by heart but I needed to see his writing.

24, Hanover Square

London

April 20th 1790

My Dearest Amelia,

Four long months in London and already I’m sick for home. I ache for the wind to howl through my casement – for the smell of the moor, the tang of salt in the air. I long for the sound of the cattle, the sheep bleating, the incessant clucking of hens. I miss the chatter of the milkmaids, the first streaks of dawn lighting the purple heather. I miss everything about Pendowrick, but that’s nothing to how much I miss you.

Father has introduced us to his business associates and I truly believe his motive for bringing us here is not to put us to work but to show us his true nature – a nature I’m beginning to find not to my liking. Francis and I are paraded round town, following in his wake like wide-eyed puppies. I believe Father finds our country manners amusing and though Francis does his best to please, I find London society shallow and insincere.

Perhaps once we’ve been truly put to work I might feel better but in the meantime, I will endeavour to learn everything there is to know about spice. Father has given us both a silver nutmeg; it’s finely engraved and has space for a whole nutmeg and a small grater. Apparently, we’re to take them with us to his gambling parties – to grate fresh nutmeg into our punch.

Are you well, my dearest love? Your seventeenth birthday seems such a long time ago. Even with the spring sunshine, I wish I was back with you, watching the firelight flicker across your face as you open your presents.

You alone are all I live for. I’ll do my duty here to Father. I’ll obey him as he has so ordered, but on the stroke of my twenty-first birthday, I’ll leave London and return like he has promised. We’ll be married by your brother and I shall never leave your side. I’ll become eccentric like your father and you can wear garlands in your hair and roam barefoot across our pastures like your mother. Pendowrick will be a haven of love and our children’s laughter will ring from every room.

Believe me, I’m counting down the days. Until then,

I remain,

Your loving fiancé that adores you, Edmund

I added another log to the fire, watching the red embers sparkle. I had waited five months for his next letter, racing down the stairs at the sound of each post; twenty whole weeks of wondering what could be stopping him from writing.

24, Hanover Square

London

September 21st 1790

My dearest, true love,

How your letters burn my hands and how I crush them to my lips. Every night when Father finishes ranting, when we nod to the servants to take him to his bed, I take your letters and hold them to my heart. Only then do I feel at peace.

Francis doesn’t find it quite so objectionable that Father is a drunken sop, but I find it embarrassing and I long to leave London. I long to breathe our fresh Cornish air and hold you in my arms. Christmas will soon be here. The first day I’m back we shall run to the clifftop where last we kissed. I do nothing but picture it – your hair will be blowing in the wind, your cheeks glowing, and I will fold you in my arms and hold you so tightly that you’ll fear I’ll never let go.

I love you every moment of every long day, and every chime of every wakeful night. Yesterday, I was reading Hamlet and found the exact words to describe how I feel.

‘For where thou art, there is the world itself, And where thou art not, desolation.’

I remain your loving fiancé, Edmund

I reached for his third letter and the familiar knife stabbed my stomach. Edmund had not come home for Christmas, nor for my eighteenth birthday.

24, Hanover Square

London