Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

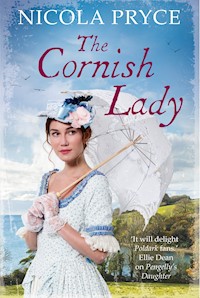

- Serie: Cornish Saga

- Sprache: Englisch

The fourth novel in a stunning romance series set in eighteenth-century Cornwall, perfect for fans of POLDARK. Educated, beautiful and the daughter of a prosperous merchant, Angelica Lilly has been invited to spend the summer in high society. Her father's wealth is opening doors, and attracting marriage proposals, but Angelica still feels like an imposter among the aristocrats of Cornwall. When her brother returns home, ill and under the influence of a dangerous man, Angelica's loyalties are tested to the limit. Her one hope lies with coachman Henry Trevelyan, a softly spoken, educated man with kind eyes. But when Henry seemingly betrays Angelica, she has no one to turn to. Who is Henry, and what does he want? And can Angelica save her brother from a terrible plot that threatens to ruin her entire family?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 580

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

NICOLA PRYCE trained as a nurse at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. She has always loved literature and completed an Open University degree in Humanities. She is a qualified adult literacy support volunteer and lives with her husband in the Blackdown Hills in Somerset. Together they sail the south coast of Cornwall in search of adventure.

Also by Nicola Pryce

Pengelly’s Daughter

The Captain’s Girl

The Cornish Dressmaker

First published in paperback in Great Britain in 2019 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Nicola Pryce, 2019

The moral right of Nicola Pryce to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 385 9

E-Book ISBN: 978 1 78649 386 6

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For my Irish mother,Moyna Snelson

Family Tree

TRURO

PERREN PLACE, PYDAR STREET

Lady Boswell

Friend of Silas Lilly

Sir Jacob Boswell

Friend of Edgar Lilly

Molly

Housekeeper

Grace

Maid

Henry Trevelyan

Visiting coachman

TRURO THEATRE

Theodore Gilmore

Actor/Proprietor of theatre troupe

Kitty Gilmore

Actress

Geryn

Actor

Hannah

Actress

Flora

Actress

TRENWYN HOUSE

Admiral Sir Alexander Pendarvis

Friend of the family

George Godwin

Prize agent

Daniel Maddox

Plantsman

Jethro

Groundsman

Bethany

Maid

Moses

Gardener

Capitaine Pierre de la Croix

French captain on parole

FALMOUTH

Lord Dexter Entworth

MP/JP/Local landowner

Robert Fox

Ship broker/Importer/US Consul

Elizabeth Fox

Philanthropist

Luke Bohenna

Physician

Mary Bohenna

Friend of Hermia

Eleanor Penrose

Concert pianist

Joseph Emidy

Ship’s fiddler

Sir Edward Pellew

Captain of HMS Indefatigable

PENDENNIS CASTLE

Captain Fenshaw

Acting Captain of Company of Invalids

Isaac Evans

Private

Patrick Mallory

Private

Martha Selwyn

Prison visitor

Stay, O sweet and do not rise!

The light that shines comes from thine eyes;

The day breaks not: it is my heart,

Because that you and I must part.

John Donne

Prologue

The Play House, Exeter

Wednesday 27th July 1796

Dearest Angelica,

We leave for Truro tomorrow. The performance next Saturday starts at 7:30 p.m. Come round the back so no one sees you – Theo will be waiting for you at 6:30. Mary Bohenna is also expected.

Yours in anticipation,Kitty Gilmore

Trenwyn House, TrenwynThursday 28th July 1796

My dearest Angelica,

Think no more of it – don’t blame yourself for a moment. We understand you must host your father’s dinner on Saturday. One day’s delay will make no difference, though we are impatient to have you here.

Until Sunday, Your dearest friend,Amelia

Perren Place, Pydar Street, TruroFriday 29th July 1796

Dearest Amelia,

And now I hear Father expects us to leave very early on Sunday morning, so I’m afraid you must expect me with the dawn! How can Father think that it is in any way polite? How I hate these last-minute changes.

Your dearest friend,Angelica

Trenwyn House, TrenwynFriday 29th July 1796

Dear Mr Lilly,

I will not hear otherwise – you must allow us to collect Angelica. Your journey to Bristol is quite far enough without adding the distance to Trenwyn. My coach will arrive at ten o’clock.

Yours in friendship, Clarissa Carew

My planning had gone smoothly – no need to forge signatures or change dates. Lady Clarissa had not written Sunday and Father would never think different; Molly would be angry, but she would soon come round.

She Stoops to Conquer lay open in my hands but already I had it by heart; every line on every page, just like my dearest mother.

Enter Stage

Chapter One

Perren Place, Pydar Street, TruroSaturday 30th July 1796, 10:30 a.m.

Above us, the storm clouds seemed to be lifting. ‘Father, perhaps you shouldn’t delay any longer. Maybe you should go while there’s this break in the rain?’

Father frowned, buttoning up his travelling coat. It was black like all his clothes, well cut and made of the finest quality, but plain and unadorned – almost too severe. He seemed more nervous than usual, all too aware of Lady Boswell’s growing displeasure.

‘No, no…we must wait and see you safely off.’ He reread the letter in his hand. ‘Lady Clarissa definitely says the carriage would be here for ten o’clock. They must be delayed on account of the rain.’

Lady Boswell shrugged her elegant shoulders. ‘Is Angelica’s comfort to be considered and not my own? Dear me, perhaps I was mistaken to accept your kind offer…perhaps I’d have been better hiring my own post-chaise?’ She smiled and I watched Father melt. She had it to perfection: the coy rise to her eyebrow, the sudden pout accentuating her high cheek bones. ‘Your horses are impatient to be off…and we’ve such a long way to go.’

As if in league, the horses lurched against their harness and Father reopened his fob watch. ‘Don’t wait, Father. Lady Clarissa’s coach can’t be much longer – you’ll probably pass it on the new bridge.’ I caught Lady Boswell’s sideways glance, her obvious triumph, and an icy hand clutched my heart.

Silas Lilly was certainly a good catch – in his sixties, he had the energy and enthusiasm of a man twenty years his junior. His greying hair was still abundant, his shoulders straight and strong. He might be a little rough around the edges for the politest society, but that was not going to stop her. Wealth was wealth, and she was clearly prepared to overlook the fact that he had been born the son of a foundry worker. Perhaps she was thinking of teaching him her manners: her ability to walk right past people in need, her inability to think of anyone’s comfort except her own.

The luggage was piled high on the roof, secured by a heavy tarpaulin. Almost everyone was going – Father’s groom, his valet, his clerk.

‘Two months is a long time to be away from home,’ I whispered.

He had chosen his strongest mares. The stables were now empty, the grooms taking the remaining horses to our farm on the moors. Molly and Grace were to clean the house from top to bottom and I would spend the rest of the summer with Lady Clarissa and Amelia at Trenwyn House. By the end of two months, Father would have negotiated a new smelting house in South Wales, the horses would be rested, the house sparkling, and Lady Clarissa would have secured my engagement to Lord Entworth.

Only Lady Boswell was beyond my control.

We always attracted onlookers when the carriage left, but today the crowd seemed distant and hostile. They stood watching in silence, hunching together with stooped shoulders. Our house was one of the larger properties on Pydar Street; it had thick cob walls and stone mullion windows, heavy crossbeams and a grand wooden staircase. The thatch had long since been replaced by slates, our five brick chimneys dominating the roofline. Seventy years ago, it was considered the best Truro could offer, but the road was now too busy, our lack of privacy causing Father concern.

A year ago, Father would have left among smiles and waves, small boys chasing after the carriage, but this group stood bedraggled and grey-faced, staring at us from beneath the shelter of an overhanging branch. Their clothes seemed to hang off them, filthy rags wound round their feet in place of shoes.

Molly sighed, shifting her stiff hip.

‘Can you find them something to eat?’ I asked.

She nodded. ‘I’ll make them some soup from the leftover mutton.’

Father was helping Lady Boswell into the carriage but at least they were leaving.

‘I don’t like this one little bit,’ I whispered.

‘Nor me neither – ye know what they say about two people goin’ on a journey…’ She shook a crease from her dress. In thirty years, she had never allowed anyone to see her wearing her apron at the front door, always leaving it on a large hook behind the kitchen door. ‘They say her first husband was too old to survive the wedding night…an’ her second husband gambled away all the money. They say she’s not a penny to her name.’

Lady Boswell’s eyes were accentuated by the royal blue of her velvet travelling jacket. Her hair was the colour of corn, her mouth reddened with pigmented beeswax. The coy smile was back, a slight flutter to her eyelashes. Her hand with its frill of Belgian lace lingered on Father’s and my uneasiness spiralled.

‘He’s only taking her to her sister – then he’s going up to Bristol,’ I said with more hope than conviction.

Molly’s mouth tightened. ‘If ye ask me, she looks like the cat that’s got the cream…’

‘Oh, don’t say that.’

Molly was hiding her dislike of Lady Boswell very well, smiling and nodding to Father as he approached, and I knew to do the same.

Father snapped his watch open and shut. ‘I really think we ought to leave, Angelica, though I’d rather see you off first… the roads are awash and I’d like to get through the turnpike before the next shower. But…well…give Lady Clarissa my best regards…and…and, well, I’m sure she’ll be successful.’ He lowered his voice. ‘The man’s enamoured of you. You’ve bewitched him – he’ll have no other.’ He nodded and bowed, my stiff and formal father, never bending to kiss me, nor chucking me under the chin, nor pinching my cheek, nor showing me any love; my prosperous father, already treating me like I was the next Lady Entworth. ‘You’ve packed my address in Swansea?’

I nodded. ‘I’ll write and tell you everything – Amelia says Lady Clarissa wants to teach me how to play cricket!’

The hard lines round his mouth softened for the first time in seven years, four months and three days. He even seemed to smile. ‘Ah, cricket! It’s a long time since I’ve played cricket.’ He seemed embarrassed by his sudden outburst, glancing quickly at the carriage. ‘We’ll be off then. Take care, Angelica. Goodbye, Molly – two months of no cookin’ will do you the world of good. Almost a holiday!’

She curtseyed stiffly. ‘Ye think cleaning’s a holiday, do ye, Mr Lilly? I’ll be thin as a rake when ye return!’

Our smiles were as false as the silk flowers on Lady Boswell’s over-large hat. Father and Lady Boswell were in the carriage, the others squeezing next to the driver or balancing among the boxes on the back seat, and with the door firmly shut their sudden intimacy was hard to witness.

‘What do they say about two people going on a journey?’

Molly’s lips tightened. ‘They say they come back married.’

‘They better not!’ I stared at the receding coach. Father had not looked me in the eyes, neither today nor last Sunday when Lady Boswell had taken my place in church, returning the congregation’s astonished stares with her particular look of triumph.

Molly slipped her arm through mine. ‘We mustn’t blame him, my love. Yer father’s a full-blooded man, an’ she’s very beautiful – though no one can ever come close to yer dearest mamma.’

‘Father has…’ I could barely say the words. ‘Father has stopped his payments to that woman.’

I knew she would sniff with disapproval. ‘Has he now! Well, that’s a sure sign – pigs will fly if Lady Boswell don’t get her way.’ Her voice softened. ‘But think on it, my love… if ye’re to marry Lord Entworth, ye father will be all alone an’ you’d only fret – whether ye like it or not, someone’s got to take yer dear mamma’s place.’

‘No one can take her place.’ My desire to cry was almost overwhelming. Father did not know half of what I did – giving alms on his behalf, generous donations to the hospital board. He had no notion I knew all his business and could forge his signature, no idea I knew where to find the keys to his desk. That was how I knew he kept a fancy woman.

In the sun, the houses of Truro would shine like gold, but today the street looked grey, a steady stream of rainwater overflowing the gutter on the other side. The profusion of carts never lessened; the constant tread of mules on their way to and from the mines. If it was not coal or tin weighing them down, it was furze or manure, the mules thinner now, in need of oats. I held my handkerchief to my nose.

Mamma had loved this house, and I loved it too, but Molly was right: the smell from the tannery was getting worse. The huge pits where they washed the fleeces and scraped the hides lay overflowing and stagnant, the smell so bad it made grown men vomit. Some said the water was tainted, that the putrid overflow was contaminating the leat running alongside our garden. Some said it was the cause of the sickness.

Maybe our house had seen better days, but it was right in the centre of town and I loved living so close to St Mary’s church. Everything was within walking distance. The assembly rooms were just round the corner, so too, the new library. Best of all, the wharf was so close. I loved the sound of the seagulls, the smell of the ships, the wind blowing salty air up the river. I loved hearing the merchants haggling on the quayside, watching the huge pulleys lift the cargo from out of a hold. I loved the bustle, the smell of pitch and tar and the songs the sailors sang as they scrubbed the decks.

Father’s carriage had been blocking the road. Carts were backed up on both sides, the drivers scowling and shouting as they tried to get past. The market would be in full swing; I had watched the boys drive their geese along the street, heard the bleating of the sheep as they passed beneath my window. Pigs were squealing, hens squawking, the market sellers’ cries echoing down the street.

Grace stood behind me, all round-eyed and rosy-cheeked. ‘Grace, there’s obviously been a misunderstanding. Take the luggage back inside. Leave the trunk in the hall but if you wouldn’t mind taking the valises and hatboxes back to my room?’

Molly’s face turned ashen. ‘But, Angelica…Lady Clarissa’s carriage will be here any moment…’ She knew me too well and her hands flew to her bosom. ‘Oh, dear Lord…what have you done?’

‘Lady Clarissa isn’t sending her coach until tomorrow,’ I whispered. ‘Kitty Gilmore’s in Truro tonight, but I suspect you already know that. I’m sure that’s why Father was so insistent I left today. We’re going to the theatre tonight, Molly – both of us. You’ve got a ticket for the front row, and I’m to meet Theo round the back. I’ve arranged everything. Nothing can stop us.’

Black clouds were circling the town, letting no light through the small leaded windows. Molly had her hands full, so I lit two candles, quickly returning to the pine table and the well-thumbed script. ‘So Tony Lumpkin tricks Mr Marlow into believing Mr Hardcastle’s an innkeeper and Miss Hardcastle’s the maid. And she goes along with—’

Molly sniffed. ‘I don’t like it.’ Her voice was clipped, her lips tightly pursed. ‘Not one little bit.’

‘No, wait…It’s good because Mr Marlow finds talking to high-born ladies very difficult.’

‘Ye know very well what I mean. I don’t like ye lyin’ to yer father – nor ye lyin’ to Lady Clarissa.’ She chopped an onion, thrusting it into the huge pot. Wiping her eyes on the corner of her apron, she shook her head again. ‘It’s deceitful an’ no good will come of it. Ye’ll be seen! Honest to God, ye’ll be seen, an’ ye father will think me part of the plan. Ye know full well Mr Lilly’s rules about the theatre. And as fer ye writin’ to Kitty Gilmore – that was the first thing yer father forbid!’ She reached for another onion, giving it less mercy.

I knew Molly would not hold out for long. ‘I really won’t be seen – I’m to go round the back and Theo will let me in. You don’t need to come; but I won’t abandon Mamma’s friends like Father has. They’re dead to him – just like Mamma is – dead and dispelled from his thoughts.’ I fought the lump in my throat. ‘Mrs Bohenna’s going to be there, so you must come – Mamma’s two best friends – Kitty Gilmore and Mary Bohenna. You haven’t seen either since Mamma died…’

‘Oh, my love…ye know I want to see them.’

‘Well, there you are. Anyway, even if Father was here, I’d still go. I’d just climb out of the window.’

Molly placed her palms on the scrubbed table. Her eyes caught mine and she took a deep breath. ‘I’m not sayin’ I’m not comin’…course I’m comin’…ye don’t think I’d give up a chance like this, do you? It’s just the shock…an’ the worry Lady Clarissa will find out.’

Dearest Molly, always my willing accomplice. ‘No one will recognize me and no one will ever know. I’ve planned everything – I’ve kept back a charity dress and I’ve stitched a huge veil on that old bonnet. No one will know it’s me – nothing can go wrong.’

Sudden footsteps caught our attention and we turned to see young Grace hurtling down the stairs, almost falling into the kitchen. ‘Miss Lilly…quick…it’s Mr Lilly. Not old Mr Lilly…but Young Mr Lilly…’

Molly’s hand flew to her chest and I slammed the script shut, pushing it beneath an empty basket. ‘Edgar? He can’t be…he’s in Oxford.’

‘Sir Jacob’s come as well. They’re just gettin’ out…’

‘Not Jacob Boswell. Not him as well!’ Molly’s face mirrored mine. Mother and son – two prongs in the same fork.

Chapter Two

Iran along the hall, pulling open the front door. Edgar had stepped from the carriage and was looking up at the house, his fine cut-away jacket and embroidered silk waistcoat the height of fashion, but he looked thin, his face deathly pale beneath his unruly black curls.

‘Edgar! What are you doing here?’

I ran down the steps, flinging myself into his arms, horrified to feel his shoulder blades through his jacket. His breath smelled of tobacco, I felt a fine tremor in his hands.

‘Father not here?’ He seemed strangely nervous, looking over my shoulder at the empty doorway.

‘You’ve just missed him – he left this morning. He’s gone— On business.’ I stopped myself just in time; Father’s plan to build a smelter in South Wales was to be kept secret at all cost.

‘Well, never mind, we did our best.’ He kept hold of my hands, turning me round. ‘Let me look at you – goodness, Angelica, you’re every inch the lady. Lady Entworth, if I’m to believe the rumours.’

Perhaps he was ill. Perhaps that was why he had come home from Oxford. Jacob Boswell certainly looked well. He had his mother’s extravagant taste in clothes, her thick blonde hair and her aristocratic hauteur. He was laughing, smiling down at me, the Boswell blue eyes meant to be working their magic, yet I would not look at him, acknowledging him only with the briefest of nods.

He shouted to the coachman: ‘Take the carriage round the back…’ He was so assured, looking up at the house as if his mother had already sold it. ‘There’s stabling round the back – plenty of room for the coach.’

His assurance startled me. I had not seen him for nearly a year but, at twenty, he had become a commanding figure, a lion where my brother was a mouse. I was two years their senior, this was still my house, and by the way he was behaving he had to understand that. The wheels of the carriage were muddy, the door newly splattered, yet the horses looked lively and there was no sign of luggage. Edgar saw my frown.

He glanced at Jacob. ‘We’ve left our luggage at the inn… it’s by the river. We arrived late last night and thought it best not to disturb you. We’ve been given very fine rooms and we thought we’d stay there…’ His laugh had changed. A year ago it would have been a proper laugh but now it was a high-pitched giggle and my heart froze. His cheeks looked gaunt, his heavy black brows too dark for his face. He saw Molly and ran up the steps. ‘Molly, lovely to see you. How are you?’

I caught her look of horror. ‘Goodness…Edgar Lilly, ye need fattening up. Has Reverend Johns not been feedin’ ye? Come here, my love, yer father’s not here so we can have a hug.’ She clasped him to her bosom. ‘What a shame ye missed him…he’ll be that sorry. Come, let’s see what I can find ye to eat…’

Jacob Boswell was about to follow but I held up my hand and his eyes caught mine. ‘Angelica…your anger’s misplaced. It’s not of my doing.’

His jacket was blue silk, his waistcoat heavily embroidered. His cravat was pinned with a silver brooch, matching silver buttons on the cuffs of his jacket. He looked well fed, staring down at me with a look of insolence, and I tried to keep calm. ‘A year ago you joined my brother in his lodgings and his expenses doubled. Father’s fondness for your mother persuaded him to increase Edgar’s allowance and yet again, his expenses doubled. Six months ago, Edgar writes to tell me of his gambling debts. His debts, Sir Jacob, when I know full well he does not gamble, or rather, he never gambled when he was here. I paid them, at once, without Father knowing, and then I received another letter. Another twenty pounds needed – on top of the already increased monthly allowance.’

A smile curled his lips. ‘Oxford’s an expensive place…’

‘So it seems. And yet, there are no bills for books, just bills for dining out? How much claret does my brother need? No, don’t answer.’ I looked up. The coachman had turned round and was staring at me. I lowered my voice. ‘Now you take rooms in an inn instead of staying here? And who’s paying the hire of this carriage? I suppose I must expect both accounts?’

A year ago, I might have smiled back into his handsome face, framed by its golden halo, but not now. Now, his influence over my brother seemed almost sinister; a huge, golden Apollo, overshadowing him with his brilliance. If Edgar had come on his own I might have had a chance to get my brother back, but not now.

The coachman was sitting on his seat, straight-backed, staring ahead, and I called up to him. ‘I’m afraid the grooms have all gone to the country so there’s no one here to help you. There’s plenty of stabling – you’ve all the choice you need. There’s straw to be had but no oats – they’ve taken the oats with them.’

‘Thank you. I’ll see what I can find.’ His heavily layered coat looked damp, his two hands in their thick leather gloves gripping the harness as the horses shook against their bridles. His face was slender, sunburned, his chin covered in rough stubble. Beneath his wide-brimmed hat his brown hair was cut short, his round-rimmed glasses taking me by surprise. ‘Oats are in heavy demand – I’m not surprised they’ve taken them.’

He was softly spoken, his tone respectful. He was clearly educated, his high cheek bones and round-rimmed glasses giving him the look of a scholar, and I glanced back. ‘Let me know if there’s anything you need.’

‘Thank you, Miss Lilly.’ Through his glasses, his eyes held mine – fiercely intelligent eyes, fringed with dark lashes – and my heart jolted. ‘Do I know you?’

‘No, Miss Lilly. My name’s Henry Trevelyan.’

I remembered names and I remembered faces and now I looked more carefully, I could see I was mistaken. ‘Don’t draw water from the leat, Mr Trevelyan – we think it’s tainted. Only use water from the pump at the front.’

He touched his hat and I turned to see Jacob Boswell towering over Grace. He was smirking, raising his eyebrows, clearly enjoying her discomfort, and my dislike of him spiralled. Grace’s cheeks were crimson and I put my hand on her shoulder, ushering her inside. Behind us, Jacob Boswell’s laughter echoed round the hall.

‘Oh, Angelica, we could be such friends…if only you didn’t think so ill of me.’

We ate at five. Mamma’s silver serving dishes glittered in the candlelight; the birds on her Sèvres china placed exactly how she liked them. Her finest crystal glasses glowed red with Father’s best claret, the centrepiece of fruit at just the right height. Edgar slumped even lower in his chair. ‘I see Father hasn’t changed anything…’

‘Why should he?’

I bit back my annoyance. This was Mamma’s room; Mamma’s beautiful green wallpaper with her matching silk stripes on her mahogany chairs. The gold mirror above the mantelpiece had been her pride and joy; her favourite chair still by the window. On good days, sunshine flooded the leaded windows, lighting the faces in the portraits opposite, but today the heavily laden sky filled the room with gloom. If she had lived, Mamma could have had everything ten times over. She could have had her grand house in the country, any number of carriages. She could have boasted a town house bigger than Mansion House.

Jacob Boswell refilled his plate but Edgar had no appetite, nibbling half-heartedly on a chicken leg and reaching for his wine. Dark curls lay limp against his face, his gaze listless. He seemed reluctant to talk and when he did, he kept deferring to Jacob. I could not eat, but listened in mounting dread. They had not come straight from Oxford; they had been away some time, staying with a friend.

‘Did you not think to tell me you were coming?’

Jacob Boswell did not even look up. ‘We thought we deserved a spot of fishing and shooting…’ He winked at Edgar. ‘But we’re bored with country pursuits…we’ve come to town for sport of a different kind.’

I could feel my cheeks redden. That man had to be stopped. They both had to be stopped. ‘You’re meant to be in Oxford, Edgar – having private tuition. Father went to a lot of trouble to find Reverend John. He’s very well considered…many people wanted his expertise. Father’s gone to a lot of expense…’

Jacob Boswell must have caught the steel in my voice. He put down his napkin, flicking the lace at his sleeve. ‘We’ve been granted a small holiday, Angelica – it’s our summer break. We are allowed out every now and then. Anyway, we’re on our way to Oxford – another week and Reverend John will have Edgar straight back in harness.’

Edgar’s cheeks looked sallow in the candlelight; he seemed distracted, restless, a strange nervousness making him fidgety. ‘Straight back in harness,’ he said sullenly, nothing like the brother I knew and loved.

Jacob Boswell pushed his plate away and reached for a folded newspaper, leafing idly through the pages. ‘Lord Carew’s won first prize for his Devonshire bull – that should put him in good humour for your visit.’ The next page held an advertisement for Kitty’s troupe and my heart began thumping. It immediately caught his attention as I knew it would.

‘Here’s something of interest…’ he said, sitting forward, clasping the newspaper in both hands. ‘Truro’s very own theatre is playing host to Mrs Kitty Gilmore’s highly acclaimed production of She Stoops to Conquer by Oliver Goldsmith. Mrs Gilmore, a much-loved star of the London stage, has taken this production all over Britain, and we are honoured to welcome her. Well, that can’t be missed, can it?’

Edgar’s eyes caught mine. ‘Kitty Gilmore?’ His mouth hardened; a slight quiver in his voice. ‘Mother’s friend, Kitty Gilmore? No wonder Father left in such a hurry.’

Lady Boswell’s eyes were in the room and I knew to be careful. ‘You know we’re forbidden the theatre.’

Edgar stared at Mamma’s empty chair. ‘And we mustn’t go against Father’s wishes, must we?’ The lines round his mouth tightened. ‘We’re to work…work…work. We’re to be as miserable as sin and take no pleasure…’

The bitterness in his voice sliced my heart. Jacob Boswell was leaning back in his chair, raising his smug eyebrows.

‘It’s against Father’s wishes,’ I repeated. ‘Anyway, I’m travelling tomorrow so I’m going to have an early night.’

‘Oh, come on, Angelica. Where’s your spirit?’ Jacob Boswell sneered. ‘I’ll find us a way to get tickets.’

Edgar slammed his hands on the table. ‘Christ, I need air…’ He stood up, his chair clattering to the ground, his plate crashing into pieces on the flagstones. ‘I can’t breathe in this place…it’s like a bloody tomb. Get the carriage – let’s go where there’s some life.’ He kicked the fallen chair. ‘It’s nothing but a morgue…a bloody morgue.’

I got up, backing slowly away. Another plate was swept to the floor. Another and another. He seemed consumed by frenzy, his faced screwed tight. He reached the door and I called after him. ‘Edgar – you should be in Oxford.’

He swung back, his sunken eyes burning mine. ‘Christ, Angelica…what are you – my gaoler or something? Get the carriage, Jake – let’s go where we’re wanted.’

Through the silence, Grace cleared the table. She was just thirteen and her hands were trembling. My heart was still thumping from the violence of the quarrel but she looked petrified and I tried to reassure her. ‘He’s just not himself…I’m sorry, Grace, he should never have shouted like that.’

She took a deep breath. ‘Wasn’t that. I’d forgive Master Lilly anythin’.’ She turned and my stomach tightened. ‘Miss Lilly…ye know ye always tell us we should speak up? Well, Sir Jacob caught me unawares…he thrust himself against me…really thrust. Said ’twas an accident but he held me… here.’ Her young face went scarlet as she pointed to her chest. ‘’Twas no accident…’twas really horrible…’

I gripped the table, trying to breathe. He was a bully, and bullies must be faced. Your mother was a whore. I was back in the school dormitory sitting on the iron bed, forcing back my tears. Mamma was a renowned actress, she was not a whore. She was beautiful and intelligent. Never shout back, that made them laugh louder–all of them sneering like Jacob Boswell, disdain dripping from their pedigree noses. Well, they would soon eat their words. When I was Lady Entworth, they would all eat their words.

Jacob Boswell’s command rang across the cobbles – ‘Coachman – bring the carriage to The Red Lion’ – and I glanced out of the window. The coachman was reading beneath the overhang of the stable, quickly tucking a marker between the pages of his book. A frown creased his forehead; he placed the book in his waistcoat and reached for his coat. ‘You’re due at your sister’s tonight, aren’t you, Grace?’ I said, watching the coachman from behind the green velvet curtain. ‘Go at six, just as we arranged. If there are dishes left over you can wash them in the morning.’

‘Thank ye, Miss Lilly…I’ll try an’ get them finished before I go.’

Molly came to my side, a huge tray held sideways against her hip. ‘Three plates broke and two glasses.’

The coachman glanced in my direction and I drew quickly back. He was pulling on his gloves in no particular hurry and I bit my lip.

‘Edgar didn’t even say goodbye. He’s changed so much.’

Molly, too, looked distraught. ‘I remember the night he was born – the nights both of ye were born. I used to rock ye in yer cradles – sometimes long into the night. Yer dear mamma was so proud…wantin’ to give ye everythin’.’

‘She did give us everything – and she’d be furious at his rudeness.’

‘He’s young, Angelica, and young men don’t like bein’ cooped up. I’d say he’s over wrought, poor boy – next week he’ll be back in Oxford, reclinin’ all that Latin.’

Despite my sadness, I burst out laughing. ‘Declining, Molly. It was the Romans who reclined.’

‘Declinin’, reclinin’ – it’s all the same. What that boy needs is fresh air an’ good food…an’ to get away from that leech, Jacob Boswell. He’s bad, that man. Like a rotten apple.’

Molly wrapped her cloak around her, pulling the lace on my bonnet to well below my chin. She locked the back door, giggling nervously. ‘There, ’tis done…now don’t ye go gettin’ seen, young lady…’ She was wearing her Sunday best, a tinge of rouge on her cheeks.

It was not the first time I had slipped from a house at night and it would not be the last. At school, I would leave the dormitory and run silently down the vast staircase, squeezing out of the small, top window in the laundry room. Through the branches of my favourite tree, I would watch the watery badgers playing in the moonlight, hoping, praying, that Mamma was somehow looking down on me. I would feel her with me, hear her soft Irish accent, and, through my tears, I would promise to fulfil her dearest wish.

My charity gown was drab and ill-fitting. ‘No one will recognize me,’ I said with absolute certainty. I glanced up. ‘There’s a patch of blue in the west – this drizzle might clear.’ I opened my umbrella. ‘We’ll go through the back gate and cut along the leat.’

‘The road’s already blocked.’ Molly slipped her arm through mine, smiling up at me. ‘There’s not been a crowd like this since Sarah Siddons came fer the theatre’s grand openin’.’ She glanced into her embroidered bag. ‘Honest, Angelica – am I really to sit in the front row?’

Chapter Three

Our land at the back stretched down to the leat. We had an orchard, a large kitchen garden. Geese grazed the grass, hens pecking and clucking amongst the mares in the stable, but with the chickens locked away and the horses at the farm, the yard seemed eerily quiet. ‘Come, I’ve got the key.’

Mamma had once thought to have a fountain built, a rose garden, even a terrace, but I think she loved the simplicity of the garden. A dovecote stood among a jumble of shrubs, an upturned wheelbarrow, a lone blackbird singing from an overgrown hedge. My hem brushed against some lavender and scent filled the air. A huge brick wall skirted the boundary, the back gate stiff on its hinges. The lock was rusty, the key difficult to turn. ‘We’ll follow the leat and double back so it looks like we’ve come from the quayside.’

I felt breathless, excitement making me walk too fast. Molly’s hip must have been paining her but her smile matched mine. The water in the leat looked murky; the grey drizzle making the path slippery and I held her elbow, ushering her along a back passage where the slops were thrown. I held my breath. ‘Mind – lift your skirt. Thank goodness we’re wearing stout shoes.’ The path widened and we stepped on to the smart new cobbles of King Street.

A long line of carriages stood at a standstill, the coachman shouting and protesting as people pushed against the horses. The line led almost out of town, expensive hats leaning from the windows, feathers fluttering as angry shouts rang down the street. People were disembarking, deciding to walk rather than wait, and the coachmen were despairing. The crowd was growing by the moment, the excitement palpable.

Everyone was laughing, smiling, dressed in their finest, linking arms as they walked up King Street and into High Cross. This was the new Truro: elegant houses with their large sash windows sweeping majestically up to the assembly rooms, curving round to St Mary’s church with its new iron railings. The queue to enter the theatre was thickening, everyone looking up at the symmetrical façade and imposing pediment, pointing to the circular reliefs of David Garrick and William Shakespeare. I pulled Molly aside. ‘Here, take your ticket. There’s a lot of people at the door – take care you don’t get crushed.’

She nodded, her eyes wide with excitement. ‘I’d no idea there’d be such a crowd.’

St Mary’s church was just in front of me, the steeple pointing sharply into the grey sky. The clock struck the half-hour and I knew I must hurry.

I did not need to. Theodore Gilmore was waiting for me, smoking his pipe by the back door. ‘Oh, just wait till Kitty sees you.’

He was just as I remembered him – tall and well built, a slight stoop to his shoulders. He shut the door, ushering me along the crowded corridor, his Irish accent conjuring up a host of memories. ‘Mind these steps…careful of this sharp corner – this shouldn’t be here but there’s no room backstage. A couple more trunks…squeeze your way past these costumes.’

I dodged the painted sets, brushing against exotic velvets and furs. Rows of hats hung from hooks, swords sticking haphazardly out of boxes. The confined corridor smelled of grease and stale sweat, the heat making me catch my breath. People were calling, rushing from room to room. A young man shot past and nearly sent me flying.

‘Hey, steady on.’ Theodore shook his head. ‘That’s Geryn – he plays Tony Lumpkin. Kitty’s in here…’ He opened the door and stood smiling proudly. ‘Here she is…’

Kitty Gilmore was at her dressing table and turned at my entrance. She was dressed as Mrs Hardcastle in a huge grey wig and an elaborately embroidered silk dress. Her face was painted white, her cheeks a livid red. She rose quickly, holding out her hands, and I lifted my veil.

‘Angelica, my dearest, let me look at you.’ She spun me round, tears in her eyes. ‘How you’ve grown these last years…’ Her voice softened. ‘Goodness, my dear, you’ve become the image of your mother.’

I was lost for words, staring back at her. Mamma had loved her so completely. They were from the same small village in Ireland; they had run away together, been homeless together. They would have starved together, had it not been for Theodore Gilmore and his friends in the theatre. Both Mamma and Kitty had auditioned and both of them had been given parts. Kitty had soon married Theo but it was Mamma who had shone the brightest, Mamma who had taken London by storm. Seeing Kitty tore my heart.

‘Thank you for sending me the script. I have the play by heart.’

Kitty Gilmore smiled with pleasure. ‘Just listen to that diction! You’re born for the stage, Angelica – born to recite Shakespeare.’

‘I wish I could…’ I stammered.

Her dark eyes seemed suddenly wistful. ‘We’ve a full house. Theo’s even had to turn people away…’ She kept hold of my hands, drawing me back to her dressing table, staring at me from the mirror as she dabbed the perspiration from her top lip. The room was a jumbled mess: bottles and jars littered the table top, a pile of clothes spilled from her chair. It was cramped and crowded, two large vases of flowers in danger of toppling off the small table. The room smelled of lilies and greasepaint, the smoke from the tallow candles making it hard to breathe. ‘We’ve taken this play all round the country…Is Molly round the front?’

I nodded as Theo drew out his watch. ‘Forty-five minutes till curtain-up. Just the last stragglers coming in – most have taken their seats. They’re enjoying the jugglers.’ He was in his late fifties but showed no sign of slowing down. Like Kitty, he wore heavy make-up and a large grey wig. The lines on his forehead cut deep into his greasepaint. ‘Flora’s late yet again. This has to be the last time. I’ll not be fooled with – there’s plenty can take her role.’ He snapped shut his watch, swinging round at the sound of running footsteps. ‘Is that you, Flora?’

The footsteps stopped and Theo held the door open to a smiling young woman of about my age. Her dress looked shabby, a slight stain down the front; her hair was lank beneath her bonnet. She hiccoughed and laughed. ‘Only ten minutes late…ten tiny…tiny little minutes. I’ll be ready in no time.’

Her flushed face and shining eyes were not lost on Kitty. ‘You’ve been drinking, Flora.’ She slammed down her brush. ‘What are the rules about drinking before a performance?’

The girl rolled her eyes. ‘One drink…one tiny, tiny little drink an’ one plate of oysters. I just stepped out for some fresh air and, purely by chance, got talking to some gentry who were comin’ to the play. They said they’d bring me in their carriage and it was them that kept me.’ She stood staring at Theo, her full red lips set in a sullen pout. ‘I’ll get changed right away…’

A bell clanged in the corridor and Theo frowned. ‘You’ve got thirty minutes.’ He held the door open, raising his eyes at Kitty. ‘Purely by chance,’ he muttered.

Kitty’s mouth hardened. ‘The girl’s a fool. She’ll be out at the end of the season.’ She added more red to her lips, tweaking a curl in her huge wig and tapped her fingernails on the dressing table. ‘There, all set. That will just have to do.’

Theo was fumbling with the buttons on his waistcoat. ‘I’ll go front of stage and see to the lamps. The wheels are mended on the garden set, so no harm done. Everything’s ready.’

Kitty stood to help him, doing up the long line of buttons with nimble fingers. ‘Geryn back in good voice?’

‘Never better.’

‘There you are, then – nothing to worry about. We’ve worked hard for this.’ She patted him affectionately on his chest, reaching up to kiss him on the lips. ‘Off you go…we’ll be right behind you.’ She reached for her fan, stooping to smell the lilies, looking up at me through her heavy lashes. ‘For a moment then, I thought you were Hermia. Honest, Angelica, you’re her absolute image.’ She linked her arm through mine. ‘I still miss her, so much.’

‘So do I,’ I said, my tears welling. ‘She would have loved this – Father left this morning.’

‘Excellent. Mary Bohenna’s coming too…’

‘I haven’t seen Mary Bohenna since Luke won his bursary and they left for London. I used to see her every day.’

‘We were three Irish girls together, all of us as close as sisters. We were as poor as church mice, yet we never gave up hope. Mary was from the village twenty miles away – she had shoes, but your mother and I didn’t.’ She clasped her chest.

‘Kitty, are you all right?’

She took a deep breath. ‘Pre-theatre nerves…that’s all. I never tell Theo I get nervous…but the truth is it never goes away.’ She took another deep breath, exhaling through pursed lips. ‘It’s passing. Come, it’s time to check everyone’s in costume.’

Kitty held back the curtain. I was standing where Mamma would have stood, seeing what she would have seen; peeping excitedly round the side of the curtain, gazing at the sea of expectant faces. I never imagined the noise, the heat, the roar of voices. ‘They’re a rowdy crowd, all right…but they’ll quieten once the music starts.’

The assembly room was transformed into a proper theatre. The front floorboards had been lifted and five musicians were settling themselves in the pit. I could see the top of a harp, a cello, two violins and a bugle. The chandeliers had every candle burning and lamps burned in a circle round the stage. People were crowded together in the top corridor, seats crammed into every available space. I could see red uniforms, blue uniforms, rows of ornate silk dresses. There were a host of familiar faces – Father’s friends, the ladies from church, several from the hospital board.

Kitty pointed to a row of seats. ‘There, those two in the middle. Look how far we’ve all come.’

I searched the crowd and my heart swelled. Mary Bohenna looked happy and prosperous, elegantly dressed in a blue dress with a fine set of feathers dancing in her hair. Her smile was every bit as lovely as I remembered. ‘She looks so well… but…surely…that’s Luke? Oh my goodness, you didn’t tell me Luke would be here!’

‘He’s Dr Bohenna now, my love. They’ve left London and he’s set up practice in Falmouth.’

I searched the face of my childhood friend. Seven years had changed him from a youth to a man – a serious man, with a furrowed brow and slightly receding hair. He had always looked studious but he had gained gravitas, a slight stoop to his shoulders. He was smartly dressed in dark but not sombre clothes, his white cravat tied in a simple bow. ‘Falmouth? Then I might be able to see them. Perhaps I can ask Lady Clarissa to invite them to Trenwyn House?’

Kitty pinched my cheek. ‘I’ll speak plainly, my dear. Mary and I have had you in mind for Luke from the moment you were born.’ She sounded so like Mamma with her lovely Irish lilt. ‘It’s time you were married – if your dear mother was still alive, she’d have seen to it long ago. But we’re here and she’s not, so it’s time to take matters into our own hands. What is it, my dear?’

I shook my head, smiling, shrugging, feeling strangely like crying. ‘I love Luke…I’ll always love him, but I can’t marry him.’ Her face slackened beneath her make-up and I knew I must tell her my good fortune. ‘Kitty, promise you won’t say anything – promise you’ll keep a secret?’ She leaned forward and I whispered in her ear, ‘It might be that I’m to marry Lord Entworth. He asked Father if he could present his suit.’ I know I was blushing. On top of a very hot room, my face was on fire. ‘Lady Clarissa is to act as my chaperone. He’s to visit me at her house and—’

‘Lord Entworth…Lord Entworth? Sweet Jesus!’ She was clearly overwhelmed but I could see she was thrilled. ‘Your mother’s dearest wish was for you to marry gentry, but Lady Entworth? Sweet Jesus, Angelica – it’s…it’s…’ She reached for her handkerchief, dabbing her eyes. ‘No. No tears…or my make-up will smudge. Just wait till Theo hears of it. I can tell him, can’t I?’

Panic filled me. ‘No, not yet…not until Lord Entworth has asked me. And…Kitty, can you call me Alice, or something like that?’

She nodded, dabbing her eyes again, ‘Of course…Well, Alice my dear, we must make tonight count – there’ll be no coming backstage when you’re married to Lord Entworth!’ She pinched my cheek. ‘We’ve ten minutes till curtain-up. You’ll not be in the way if you stay here…just keep back to stay out of sight.’

The stage had been transformed into the chamber of an old house. The players were lining up, Theo giving them last-minute instructions. Some had their eyes shut, others were taking long, deep breaths. Miss Hardcastle was to be played by an actress called Hannah Hambley; Miss Neville by the hapless Flora. I could hardly breathe for excitement. This was how Mamma must have felt; how Mamma must have stood. It was in my blood, my bones, my very soul.

Two men had lowered the chandeliers, the candles being slowly extinguished. The expectant hush made my heart thump harder. The musicians had stopped playing; it was growing darker, only grey faces where there had been such colour. Thin plumes of smoke curled from the lanterns, shadows dancing across the closed curtain. Theo nodded to an actor who flung back his head and parted the curtain. He stepped into the lamplight.

‘Excuse me sirs, I pray –’ he boomed.

Chapter Four

I watched in awe, unable to stop my laughter, enjoying the howls of mirth and stomping of feet. Geryn finished singing and the audience started yelling for more.

‘I don’t get paid to sing it twice,’ he shouted back. The stomping grew fiercer, a shower of coins raining down on him. He stooped to pick them up, placing them in a small leather pouch. ‘Well…all right then, seeing as it’s you…but don’t tell Mr Hardcastle – you know what an old skinflint he is…’

The crowd roared their approval and more coins landed by his feet; it was so loud, so boisterous, so completely thrilling. Kitty was smiling broadly; she put her hand on my shoulder. ‘He’s got a way with them – knows just how to get them going. Once he’s got them laughing, they’ll laugh the whole way through.’

It was everything I imagined – the heat, the glare of the lamps, the sea of faces. Sweat trickled down my back, my cheeks flushed, my heart racing. The audience was entranced and I laughed with them, squeezing out of the way as painted sets were wheeled back and forth. It was so cramped, yet somehow everyone avoided a collision. The third act was over, the set-change taking place. Behind the curtain, Theo’s frown deepened. He shook his head.

‘Where is she, for God’s sake? She missed several lines… What’s wrong with the woman? She looks half-dazed.’

Kitty was also frowning, glancing over her shoulder. ‘She needed the privy. Hannah’s gone with her.’

Hannah ran from round the back of the stage. ‘Flora’s got the gripes. She feels sick.’ She began pulling off her maid’s costume, stepping quickly into the elaborate silk dress Kitty held ready.

‘Sweet Jesus.’ Kitty tied the ribbons on the bodice, fluffing out the silk petticoats. She beckoned to Theo. ‘You’ll have to tell the orchestra to play – Flora’s sick.’

‘Christ, that’s all we need. I’ll get Geryn to sing again – five minutes…tell her she’s got five minutes.’

I felt their panic. Where there had been quiet efficiency, there was now definite nervousness. Geryn understood at once and nodded, stepping out through the curtain with an exaggerated smile. He held up his hands, raising his voice. ‘’Tis my opinion you’re rather a quiet lot here tonight!’ Laughter filled the theatre; there were cheers, rowdy shouts. ‘See what I mean…quiet as a mouse…now, how about I get you singing?’

Flora appeared behind me, unsteady on her feet. Her cheeks were scarlet. Kitty rushed to help her, but just one look at her flushed face and Theo shook his head. ‘Four lines missed and your words muddled.’

Flora lifted up her chin; her lips were glistening, strands of the heavy blonde wig clinging to her flushed cheeks. ‘I’ve been sick…but I’m better now. I can go on…’ Her voice sounded thin, a slight quiver as she spoke. In front of the curtain, the audience were singing. ‘Let schoolmasters puzzle their brain, with grammar, and nonsense, and learning…’

‘You look unwell.’ Kitty put her hand on Flora’s forehead. ‘You’re feverish…you can’t possibly go back on.’

Flora’s eyes filled with fear. She wiped a handkerchief across her face. ‘I’m better now…I can go back on…honest – I’m better.’ She twisted the handkerchief in her hands.

Kitty’s urgent look made my heart pound. ‘Flora hardly appears in the next scene – not for very long anyway. Perhaps she should carry on?’

‘And have her vomit on stage?’ Theo shook his head, more in exasperation than disagreement. ‘This is all we need,’ he said again. Beads of perspiration covered his forehead. He must have been burning up under his heavy costume and large grey wig. ‘I’ll not have you ruin this production. I’ll not—’

Flora cut him short. ‘Please, Mr Gilmore – I’m fine. Honest, it’s already passing…’ She looked resolute, knowing her job was at stake.

Theo picked up his cane. ‘Just this act, then we’ll see. Come, we’ve wasted enough time – and no more missed lines.’ He stamped his cane loudly on the stage, his voice booming from behind the curtain. ‘Lumpkin?’ The orchestra stopped and he shouted again. ‘Where’s that good-for-nothing, idiot boy? Up to no good, I warrant.’

From the wings, I watched Geryn stop singing and glance over his shoulder. He lifted his hat, leaning forward to draw the audience into his confidence. ‘He calls me idiot, but I’ll get the better of him…’ He paused. ‘’Tis Act Four, by the way, in case you’ve just woken.’

The audience roared their approval, but behind the curtain, I could feel the anxiety growing. The furrow on Theo’s brow deepened. He was clearly reluctant but nodded for the curtain to rise. The actor playing Hastings stepped forward, taking Flora’s arm.

She took a deep breath. ‘I think ’twas the oysters. I’ve been sick with oysters before.’

She seemed to be doing well, the scene progressing with no mishap; her three lines were soon over, spoken clearly, and I felt myself begin to relax, but once off the stage, she gripped her abdomen, bending over in pain. ‘Get a bowl… a bucket…quick.’ Her cheeks were even redder, her eyes feverish. ‘No…’tis passing. I’ll be all right.’

Theo’s face was like thunder. Hands on his hips, he shook his head. ‘Kitty, someone must take her place.’

‘But everyone’s twice her size and half her height. Sweet Jesus – what about Elspeth?’

‘No, Elspeth’s too old and they’ll recognize her as the maid. This performance mustn’t end in farce – our reputation’s at stake. One mishap, just one critic ridiculing our performance…’

Flora grasped her hands as if in prayer. ‘I can do it… honest…I can get through this next scene – and I say next to nothin’ in the last scene. I can hold out.’

Kitty must have read my mind. ‘You said you had this play by heart?’

I nodded, my heart thumping.

‘Ye know what I’m thinking, don’t ye, my love? Flora has hardly anything left to say. She only comes on at the end – she has, what, three, maybe four lines? It’s next to nothing.’ I heard the plea in her whisper.

‘But, Kitty, what if I’m recognized?’

‘In her costume? Under that wig? Angelica, you’re her exact shape and size – you’d look just like her. No-one will notice because no-one will know. Could you remember four short lines?’

I needed to say no. I needed to be sensible and answer firmly. My head knew it to be wrong but my heart…Dear God, my heart wanted it so badly. Kitty put her arm around me, staring up at Theo. ‘The audience won’t even notice.’ Theo shook his head, but he looked undecided and Kitty’s voice grew firmer. ‘All she needs do is stand in the right place. I’ll be right beside her – or just behind the curtain – and I can whisper the lines.’

Flora grimaced, clutching her belly, the pain obviously getting worse. Onstage, the play was in full swing, the audience laughing. Theo cursed, turning at his cue, striding on to the stage at just the right moment. ‘I no longer know my own house…’

Close up, Kitty looked older, the deep lines round her mouth forming cracks in her greasepaint. Her gown was dirty, smelling of sweat, the lace old and torn. She sounded desperate. ‘Flora must just get through this scene – then you can switch in the interval. Four short lines – I’ll be right next to you.’

She must have sensed my sudden resolve as a smile swept across her face. She grabbed my elbow. ‘Here, start getting changed. There’s no time for modesty…get your gown off and put this wrap on.’ She beckoned a stagehand over. ‘This is Alice – she’s an actress. She’s going to take Flora’s part.’

They began undoing the buttons of my charity gown, lifting the bodice over my head, slipping a silk dressing gown over my naked shoulders. It was not me standing there, but a professional actress, stepping out of her skirts into a change of costume. My bonnet had remained secure and I held the lace to my face, my heart pounding. ‘You’ve seen the way Flora does her make-up – put the beauty patch on your chin and make sure to redden your cheeks. The script’s on the table.’

‘We did this play at school. I played your role…’

She looked up and smiled. ‘I know – that’s why I asked you. Tie your hair back ready for the wig. When the play’s over we’ll ask Dr Luke to check on Flora.’

The actor playing Hastings was called Marcus. He looked far from convinced, holding out his arm, and scowling at Flora. ‘Not going to be sick, are you?’ She shook her head, and his mouth clamped tight. ‘On your head be it.’ Their time was up and they stepped laughing on to the stage. ‘Ay, you may steal for yourselves next time…’

‘Quick – go and paint your face.’ Kitty had hardly time to draw breath. She threw back her head and stepped on to the stage.

‘Follow me…’ The stagehand grabbed my arm, ushering me down the sweltering corridor. ‘Careful ye don’t trip – mind them fire buckets.’

Chapter Five

Flora reached for the bucket and I pulled the wig in place, the mass of blonde curls cascading round my shoulders. Footsteps stopped outside the door, Marcus peering through the gap. ‘Time’s up. You’re needed.’

The hot wig gripped my head like a vice; the silk gown, itching me, smelling of sweat but it fitted me perfectly. I was laced to within an inch of my life; I was Miss Neville and I was doing this for Kitty. We stopped in the wings and Marcus grabbed Flora’s bonnet from my hands, jamming the pins into my wig. ‘There’ll be no scene change – we’re straight on after There’s morality in his reply…’

My heart was pounding. I was Hermia’s child and I could do this. I had four short lines and I had them by heart. I would copy Flora’s walk, the coquettish toss of her hair. But my lines required a change of tone: Miss Neville was resolved not to run away and I needed to sound firm, speak with resolution.