6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

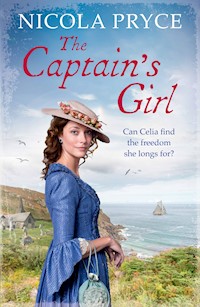

Perfect for fans of POLDARK! A stunning eighteenth-century Cornish romance, following the desperate struggles of heroine Celia Cavendish as she bravely attempts to craft her own future. Cornwall 1793 - As the French Revolution threatens the stability of England, so too is discontent brewing in the heart of Celia Cavendish. Promised to the brutal Viscount Vallenforth, she must find a way to break free from the bounds of a life stifled by convention and cruelty. Inspired by her cousin Arbella, who just a few months earlier followed her heart and eloped with the man she loved, she vows to escape her impending marriage and take her destiny back into her own hands. She enlists her neighbours, Sir James and Lady Polcarrow, who have themselves made a dangerous enemy of Celia's father, in the hope of making a new life for herself. But can the Polcarrows' mysterious friend Arnaud, captain of the cutter L'Aigrette, protect Celia from a man who will let nothing stand in the way of his greed? And will Arnaud himself prove to be friend... or foe?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

NICOLA PRYCE trained as a chemotherapy nurse before completing an Open University degree in Humanities. She is a qualified adult literacy support volunteer and lives with her husband in the Blackdown Hills in Somerset. Together they sail the south coast of Cornwall in search of adventure.

Also by Nicola Pryce

Pengelly’s Daughter

First published in paperback in Great Britain in 2017 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Nicola Pryce, 2017

The moral right of Nicola Pryce to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 885 1

E-Book ISBN: 978 1 78239 886 8

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For my children: Morwenna, Angharad and Hugh.

Contents

South-East by South

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

North-West by North

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

True North

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-one

Chapter Fifty-two

Chapter Fifty-three

Chapter Fifty-four

Chapter Fifty-five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Acknowledgements

Family Tree

PORTHRUAN

PENDENNING HALL (Acquired 1787)

Sir Richard Goldsworthy

Guest: Bow Street Stipendiary magistrate

Major Henry Trelawney

Guest: Major in the 32nd Foot Regiment

Mr Phillip Randal

Steward

Mrs Jennings

Governess

Walter Trellisk

Coachman

Ella

Housemaid

FOSSE

POLCARROW (Baronetcy created 1590)

Jenna Marlow

Companion

Joseph Dunn

Master of Horses

Bespoke Dressmaker (Est. 1792)

Madame Merrick

Dressmaker

Eva Pengelly

Seamstress

Elowyn

Seamstress

HMS CIRCE Captain Edward Penrose Lieutenant Frederick Carew

L’AIGRETTE Captain Arnaud Lefèvre Jacques Martin Nathaniel Ellis

TRENWYN HOUSE near FALMOUTH

BODMIN

Mr Matthew Reith

Attorney of law

Mrs Sarah Hambley

Guesthouse proprietor

Hannah Hambley

Daughter

Mary

Maid

Adam Tremayne

Friend of the family

Robert Roskelly

Convicted murderer in Bodmin Gaol

We only part to meet again.

Change as ye list, ye winds; my heart shall be The faithful compass that still points to thee.

John Gay

South-East by South

Chapter One

Pendenning Hall Thursday 7th November 1793, 3:00 p.m.

‘Come, Charity, I’ll race you to the folly.’

‘No, Cici, it’s too far. It’s getting late and it feels like it’s going to rain.’

Always the same sense of duty. Always reigning in when I wanted to gallop. ‘I don’t give a fig if it rains. Let it pour.’

‘I think Miss Charity’s right, Miss Cavendish. The weather’s turning…and—’

‘And?’ I turned to face him. He may be a groom but, for all of that, he was our gaoler. He looked nervous, pulling at the reins, edging in front of us so we would turn back. Do not let them out of sight of the house, was that what he had been told? They were both right, of course, the sky was darkening. We should return to our dressing rooms and prepare for the evening. I should dress in my blue organza, the better to show off the huge ring now glittering on my finger. We should sit stiffly with Mama, eat Madeira cake, drink sherry and bask in my wonderful fortune. I knew what I should do.

I looked up at the folly. ‘Itty, Viscount Vallenforth’s horse is tethered outside the folly – he hasn’t left the park. He must be waiting for us, hoping we’d ride that far.’ My heart began pounding. Father had negotiated a brilliant settlement, well exceeding Mama’s expectations, but perhaps Viscount Vallenforth felt the same as I did? The same empty longing? The dream there was more to marriage than legal negotiations and formal settlements? I felt suddenly so happy. He, too, must regret we had never been left alone together. He must be waiting, hoping I would see his horse and ride over.

‘I know you have your orders,’ I said, using as much of Mama’s tone as I could bear, ‘but think how displeased Viscount Vallenforth will be if you stop me. Take Miss Charity home – she’s getting cold and she’s tired. I’m only going to the folly and Viscount Vallenforth will accompany me back.’

The groom bowed, reluctantly turning away. I knew it was unkind to speak so sharply. He looked kind and was certainly good with the horses. ‘Very well, my lady,’ he replied, giving me every indication he recognised a prearranged tryst when he saw one. Charity looked anxious, turning to me in distress.

‘I won’t gallop, Itty, I promise. I know about the rabbit holes and I’ll take the greatest care.’ I could not go back, not now, not with him waiting for me like that. This was a tryst – a real tryst, like proper lovers, and he had chosen the folly – how wonderfully romantic. Perhaps he would kiss me. I felt breathless, gripping the reins tightly, tapping my mare forward. She was a lovely chestnut, my favourite in the stable, and I knew she was itching to canter. Sensing my excitement, she needed little encouragement and I spurred her on, ignoring Charity’s frown of concern.

I loved the folly; I could watch it all day. In fact, I frequently did. I loved the light, the changing colour. Early sun turned the marble a brilliant white, evening sun bathed it in glowing red. Moonlight turned the columns ghostly silver. Should I kiss him back? We had met twice, both formally, and on both occasions he had seemed so reserved, so very distant, but perhaps that had been for appearances. Perhaps, beneath that impeccably embroidered waistcoat was a heart beating with passion. I was blushing now, the banned books from the library distressingly vivid.

The ground was growing steeper, the final rise before the top. This was my favourite place. In a moment, I would turn round and gaze across the river mouth to the harbours below; Fosse and Porthruan – two opposing towns, fighting for dominion of the river mouth. I would see the jumble of stone houses rising steeply from the quaysides; some days, so clear, I could see the shuttered windows, the grey slate roofs, other days, smothered by a fog so thick, they would disappear completely. Today was perfect. In the evening light I could see the masts of the ships, the church tower, the solid outline of Sir James Polcarrow’s house with its sturdy walls and pointed windows. Best of all, I could see the sea – miles and miles of open sea; the clouds now gathering, the waves turning an ominous grey.

Go to Cornwall? Mama had been aghast. She never intended Father to come. Buy the house and estate and become the Member of Parliament, certainly, but to expect her to gothere? The thought had left her reeling – that was until she realised how very opportune it would be. My marriage was her prime concern, and to be within visiting distance of Viscount Vallenforth and his powerful father was enough to rouse her. It had taken seven years for her to venture down here, but only three months to secure the engagement. Once the wedding was over, Mama could leave this godforsaken wind-blown wilderness and return to her beloved Richmond.

Full-bellied clouds blew across the land, the folly nearly indistinguishable against the overcast sky. I could see Charity dismounting at the house below and knew she would be anxious. Only ten months separated us, we could not be more different and I loved her all the more for that. Neither of us called Pendenning Hall home. It was certainly a beautiful house with perfect symmetry – all four aspects equal, three rows of seven windows, the top windows slightly smaller than the ones below. It had the obligatory large front door, framed by a particularly ornate portico and a circular drive, large enough to please Mama. Even the huge fountain, brimming with nymphs and watery goddesses, had met with her approval. Terraces stretched down either side, statues eyeing each other from across the formal gardens but I felt no love for it. Father had owned it for seven years. For five months it had been our home, for the last eleven weeks, it had become our prison.

How had Arbella left the house in broad daylight – our beautiful cousin, exactly five months younger than me and five months older than Charity? I missed her so much. For a few weeks she had filled our hearts with talk of sun-drenched, turquoise seas, of blistering heat, of butterflies and humming birds; of vibrant flowers and exotic fruits growing in the gardens of Government House. She hated Dominica but I thought it sounded so exciting. How could she just walk out of our house in broad daylight, plead a headache, go to her room and escape unseen? Even more puzzling, how could she know she loved a man quite so much to be prepared to give up everything?

The mare hesitated and stopped. Rabbit holes were everywhere but the ground was still firm so I urged her on, choosing our route with care. She seemed strangely jumpy, throwing back her ears, her nostrils beginning to flare. The folly was less than fifty yards away, Viscount Vallenforth’s horse tethered on the other side, but still she hesitated, ignoring my repeated commands.

Slipping from the saddle, I grabbed her halter, examining her carefully for signs of injury. There was nothing – no limp, no reason to stop, and I began edging her forward with more force than necessary. It was strange; I always chose to ride this mare because she was so fearless. Suddenly I stopped. I could hear whinnying from the other side of the folly – the unmistakable sound of a stallion in distress. The sound unnerved us both and my hands began shaking. The mare’s fear was rising and I knew she would bolt if we got any closer. I began calming her, turning her round, desperate to get her safely tethered.

A small wood ran down the side of the hill and I ran to it, tying the mare safely to a trunk, returning quickly across the uneven grassland, grateful for my sturdy boots. The stallion was straining against the post, rearing on his hind legs, the whites of his eyes stark with fear. He was clearly petrified, his mouth frothing, his nostrils flaring in panic. My alarm increased but I knew to show no fear. To reach Viscount Vallenforth I would have to walk calmly in front of the terrified stallion, edge round the columns and enter the arch at the other side.

I stopped. I could hear a slow, rhythmical sound coming from the folly – the sound of a whip whistling through the air, meeting its target each time, the same speed, the same relentless ferocity. Worse still, I could hear grunting, the terrible grunting of a man using all his effort. I put my hands over my mouth to stifle my scream. I was right. Dear God, I was right. I had seen the cruelty in his mouth. I had sensed his coldness. In my heart, I had known.

The boy he was thrashing had long since stopped crying, his white face seemingly lifeless; his tiny, thin frame lying half-naked across Viscount Vallenforth’s knee. Angry red wheals covered his back and buttocks – all of them oozing, all glistening with bright red blood. There was blood on Viscount Vallenforth’s arms where his sleeves had been rolled and a smear of blood across his forehead where he must have wiped the sweat from his eyes. I drew back, my stomach retching.

It was the most vicious thing I had ever seen, but it was the look on Viscount Vallenforth’s face that sickened me most – that glazed, lustful look, that smile, the gluttonous, satisfied curl to his lip. The pleasurable grunting. I could see his enjoyment in such a cruel act and I bent over, trying to stop myself from vomiting. Hateful, vile man – just one more lash and he could kill the boy. Pulling myself together, I rushed in and grabbed his arm as it rose towards me. ‘Stop this at once!’

His arm went rigid, his eyes unable to focus on my face. He was looking through me, not at me, his chest rising and falling, his thin lips creased in their tight smile. I gripped his arm, wrenching it towards me, his white knuckles clenching the riding crop so tightly. As if coming to his senses, he stood up, letting the boy fall to the ground. ‘That’ll teach him. He won’t poach again.’

‘It’s not your land. Father should punish the poachers.’

‘I’ll punish who I like.’ His voice was hard, unrecognisable from the voice that had only an hour ago been sweet-talking Mama. ‘I’ll whip anyone who sets a snare and threatens my mount – whoever’s land he’s on.’ His eyes were focussing again; cold, cruel, staring straight at me as he began rolling down his shirt sleeves, carefully fastening the pearl buttons above the lace, flicking some dirt off his satin waistcoat. He turned to retrieve his carefully folded jacket. ‘You shouldn’t be here.’

I knelt on the ground, gathering the whipped boy in my arms, ‘He might die.’

‘I doubt it. They’re stronger than they look. Goodbye, my dear, I’ll see you in church.’

The boy was deathly white for all the dirt covering his face. He lay limp in my arms, his wounds bleeding, his chest barely rising. I took off my cloak, wrapping it round him, cradling him softly. How old was he, nine, ten? His thin body seemed just skin and bones as I held him to me, trying to get some warmth into his fragile frame. Poor, poor boy, I could imagine him watching Viscount Vallenforth fold his jacket, the fear in his eyes as he saw him roll up his sleeves. Had Viscount Vallenforth petrified him even further by testing the crop in the air? Somehow I knew he had.

I had hoped. I had really hoped. I had tried so hard to supress my instincts, believe in my good fortune. I thought he must be cruel. I could tell by his thin lips, his humourless face, by his arrogance, his hauteur, his distain. I had seen the cruelty, but never believed him such a brute. At thirty-nine, there must be a good reason why he remained unmarried. Others must be privy to his true character. Others must know.

The boy stirred, opening his eyes, staring at me with little comprehension. I rocked him gently, his two dead rabbits on the floor beside us. He was clearly starving, desperately in need of food and shelter but, first, his wounds must be dressed. He was almost weightless when I picked him up, almost lifeless when I carried him to the mare. She was nervous; the smell of blood clearly causing her distress. Calming her as best I could, I led her to a broken tree stump and eased myself carefully into the studded saddle. The boy barely moved.

I looked round, scanning the contour of the trees. The wood sloped gently to the river below. I had not ridden there before, the folly marking our furthest boundary, but halfway down the hill, a narrow track led straight into the woods. I urged the mare forward, slowly picking our way towards the tiny opening. Just as I thought – fresh hoof prints, digging deeply into the soft mud at the entrance. I stared at the hoof prints. Viscount Vallenforth must have been cantering. To canter, he must know the path to be sound. It must be a shortcut out of the park.

West of the river, all the land belonged to Sir James Polcarrow, east of the river, everything belonged to Father. I stared at the path as if mesmerised – the fallen leaves, the twigs snapped in half. For the first time in my life, I was unaccompanied. I could follow that path. I could walk away. In the wood, the birds were singing. The boy stirred in my arms and I flicked the reins, digging in my heel to urge the mare forward. She hesitated, as if questioning my command.

‘Walk on,’ I said, turning her westwards.

Chapter Two

The boy’s head rested against my shoulder, his tiny frame shivering. My tears were drying, my resolution hardening. I would never marry Viscount Vallenforth. Never. I would go to Polcarrow and beg Lady Polcarrow to take me in. I would write to my parents, telling them I would not come home until I was released from my engagement. It was the only thing I could think to do. The boy needed help, I needed sanctuary and, without the threat of scandal, my parents would take no notice.

‘It’s not much further. You’ll be safe soon,’ I whispered. I could visualise the way: I had stared down at the house often enough and my memory never failed me. Polcarrow was three miles from Pendenning Hall, only two miles from the folly. The path was already getting flatter, the ground growing softer by the minute. We must be halfway there.

Through the trees I glimpsed the river. The tide was out, only the thinnest stretch of water showing black against the muddy banks. It seemed strangely eerie – the trees’ roots gnarled and twisted, seaweed hanging from the white branches like long black fingers. Broken trunks lay stranded along the shore, an abandoned rowing boat with planks missing, but it was so beautiful, so peaceful. Fast grey birds darted across the glistening mud, tall white birds looked down from the trees. I forced my eyes away, turning with the path, following the fresh hoof prints pointing my way.

The path widened and stopped, the growing dusk making it hard to know where I was. Gradually I recognised a rough stone wall, a crooked post. Turning left would take us back to the gate-house, turning right would take us along the river to the bridge. Ahead lay the ford, used only when the tide was out. Our coach had driven through it, but only once. The water had been deeper then, almost to the steps of the carriage.

‘Walk on…’ I urged, kicking the mare forward, forcing her down the muddy slipway, keeping her head steady as the inky black water rose above her fetlocks. I knew not to stay on the road – if they came searching, they would come this way. For the past few weeks I had seen wood-smoke rising from these woods. Trees were being cleared; I knew to look for a small path that would take us straight to Polcarrow.

The path was smaller than I expected, hardly wider than the horse. The light was fading, the trees merging together in the gathering darkness. I could see lamps burning through the trees and knew exactly where I was. We had never been invited to Polcarrow, the animosity between Sir James and Father saw to that, but Arbella and I had gazed down from the hill, studying the stables and the coach-house, thinking she would soon be mistress of the old house. How very secretive she was then; I wished she had told me the truth, but how could she? Everyone had to believe she was to marry Sir James – how else could she run away with the man she truly loved? Her plans must have been so intricate, borne out of desperation, yet now I understood her. Dearest Arbella, to keep so silent, not telling a soul.

How very different Polcarrow was to Pendenning Hall – here was ancient woodland, a long-established house, a family name stretching back for generations. Our house was so new, Father’s baronetcy straight from the boardroom of the East India Company. Trade, as Mama would say, had she not depended so entirely upon it.

The mare saw the lights and increased her pace, picking her way more readily through the dense overgrowth. We were heading straight for the stables – unseen, uninvited, a terrible affront, but it was my only chance.

‘We’re here – you’ll be safe, now. Sir James’s a good man.’ The boy’s small arms clasped my neck and I felt him shake. ‘You’re safe, I promise. You’ll be well looked after.’ I sounded reassuring, but I was surprised the place seemed deserted, no-one there at all. ‘We just need to find someone.’

Not far away was a hitching rail and I decided to dismount. Wrapping the boy carefully in my cloak, I slipped from the saddle and carried him in my arms. Lamps were burning either side of the stable entrance; other lanterns lit the path to the house and more lamps burnt against the coach-house, but there was no-one to be seen.

I crossed the courtyard and entered the stable, at once met by the familiar smell of fresh straw. A well-run stable, that was obvious – no corners cut, no laziness tolerated. Deep straw lined every stall, the horses contentedly nudging their hay-bags. Buckets of water stood inside each gate and newly oiled saddles hung against the dark wooden stalls. My eyes were immediately drawn to two saddles lying on the flagstones. They looked to be flung to the ground and abandoned in haste, clearly at odds with the immaculate surroundings. Stranger still, two black stallions stood bridled and steaming with sweat.

A tiny glow of light lit the end stall – the flicker of a single lantern. I could hear a woman sobbing and whispered voices. The last two stalls were empty, the voices coming from within the furthest one. I knew I ought to walk away, or make my presence known, but curiosity drew me forward. It was always like this. It would be easy to slip into the second stall, hide in the shadows where no-one would see me. Knowledge was power – I had learnt that as a child. How else could I know the truth from the lies they peddled me? Cocooned in silk, the newspapers hidden? Told only what they wanted me to hear. Without listening at doors I would never know what was really going on.

I crept silently forward, stepping over the freshly laid straw without a sound. A chink of light showed through the wooden stall and I knelt down to peer through the tiny crack. There were two men, three women and a boy of about twelve. James Polcarrow had his back to me, with Lady Rose Polcarrow by his side. I did not know the blonde woman or the huge red-haired man, but I recognised Alice Polcarrow, Sir James’ stepmother. She was kneeling in the straw, sobbing, clutching her son to her.

‘When was this, Alice?’ James Polcarrow sounded furious.

She looked up, tears streaming down her cheeks, ‘This morning…at ten o’clock.’

‘Ben came to you in the garden and gave you this?’ He held up a small brown paper package.

‘Yes.’

‘And the message was, “You know what to do”.’

‘Yes.’

‘Alice, Ben’s not the best of messengers, he can barely get his words straight. How do you know what it means?’

A fresh burst of sobbing met this question. ‘I know exactly what it means,’ she stammered. ‘I’ve been dreading it for months. It’s from Robert – it’s poison. When he was arrested, Robert told me he’d get poison to me, to put in your drink.’

‘Dear God, Alice, your brother’s an evil man – you should’ve told me this long ago.’ James Polcarrow’s jaw clamped tight, his face thunderous.

‘I thought it would never happen. I just prayed and prayed, hoping we’d hear of his hanging, but when it was postponed I began to feel such dread. I was going to tell you when I heard he’d escaped from Bodmin, but you left in such a hurry.’

She wiped her tears with the back of her hand and leant forward, scooping something up from the straw. My heart froze. A spaniel dog lay with his head hanging limply to one side, his big brown eyes glazed and lifeless. She buried her face in its immaculate coat.

‘He’s poisoned Hercules as a warning I must do exactly as he says…he told me to use the poison on you, and if I didn’t, he’d take my son. He takes everything – everything. First he killed your father, now my dear, sweet Hercules and he’ll take Francis, I know he will. He just takes and takes and takes. I hate him.’ Pain caught her throat, her words barely audible. ‘He said I’d never see my son again…he’d kidnap Francis, sell him to some ship’s captain.’

‘The man’s insane.’

‘He’s always controlled me…always. You weren’t here. You were miles away. Your dear father was dead and as Francis’ guardian he took everything into his own hands. He ran the estate with such cruelty and I was powerless to stop him. I thought only to get by until Francis came of age. His greed knows no end – he wants to control Francis just like he controlled me. You’re in his way.’

I leant back against the wooden stall, clutching the boy closer. They were speaking so quietly, their voices hardly above a whisper. Robert Roskelly – I knew the name. Father had done business with him when he lived at Polcarrow and I had watched him from the window when he had come to dine. Father had liked him but Mama thought him frightful. Neither had spoken of him since he was arrested for the murder of Sir James’ father.

‘How did he escape?’ It was Lady Polcarrow’s Cornish accent, the beautiful Rose Pengelly, not three weeks married. ‘Will he come to Fosse, James?’

‘No. He’ll not come anywhere near here – he won’t risk being recognised.’

I peered through the chink again. James Polcarrow was pacing backwards and forwards, one fist tapping his mouth, the other held tightly against his side. Lady Polcarrow was kneeling on the ground, her arms round Alice and Francis. The boy looked petrified. He was tall and dark like his stepbrother. Sir James’ scowl deepened. ‘Alice, have you any idea where your brother would hide? Who would your brother trust with his life?’

She looked up, pain deep in her eyes, ‘I’ve been trying to think – perhaps Rowen Denville. I think he’d trust her. They were…well…you know, rumour had it…’

‘Where does she live?’ James Polcarrow knelt in the straw, encouraging Alice in her distress.

‘Falmouth.’

‘Then that’s where he’ll be. My guess is he won’t sail until he knows I’m dead and Francis will inherit Polcarrow. Whoever gave Ben that poison will have instructions to wait and see if you use it. If I don’t sicken, he’ll have instructions to take Francis—’

‘Dear God, James. No.’

‘Our only option is to make them believe you’ve used it. Rose and I will pretend to be ill and while Robert Roskelly waits to hear of our deaths, I’ll go to Falmouth and find Rowen Denville. I’ll base my search round her. I will find him, Alice. Your brother will hang for the murder of my father and Francis will come to no harm. That, I promise.’

I held the boy carefully against me, afraid he might whimper. Sir James turned to the other man. ‘Joseph, send to Truro for Dr Trefusis – we can’t trust any of the local doctors…and stay with Francis at all times. Sleep in his room and never let him out of your sight. Never.’

‘Yes, Sir James.’

He turned to the blonde lady. ‘Jenna, tell everyone Rose and I are fighting for our lives. Insist on being our only nurse and stop anyone coming into our rooms. Cry a lot and say we’re getting worse.’

‘Yes, Sir James.’

‘Rose,’ his voice once again softened as he looked at his wife. ‘You must stay in our bedroom and make sure you aren’t seen by anyone.’

Rose Polcarrow looked back at him through the darkness. Her chin lifted, her beautiful eyes flashed. ‘I’m coming with you, James.’

‘No, Rose, it’s too dangerous. I insist you stay here.’

She smiled, seeming to take no notice. ‘I won’t let you go alone.’

I could not believe it. Rose Pengelly, the seamstress’s daughter, contradicting her husband, yet he was smiling back at her; a deep, loving smile, the two of them exchanging a look of such love. The rumours he had hastened their marriage were true – he did love her, he adored her. I closed my eyes, trying to shut out the sight of Viscount Vallenforth’s terrible thin lips, curling in their cruel smile.

Lady Polcarrow’s voice grew urgent. ‘L’Aigrette’s still in harbour, James. I’ve been watching her from the terrace. The wind’s northerly, the tide’s about to turn – it’s perfect for Falmouth. If we hurry we’ll catch Captain Lefèvre.’

I leant against the stall, holding the boy in the darkness, the sound of their footsteps receding along the cobbles. My mind was racing. Could I? Would I dare? I remembered Arbella’s hastily scribbled note. I had burnt it, as requested, but I remembered every word – we’ll be married straightaway, but so we can’t be traced we’re going to call ourselves Mr and Mrs Smith. We’ve got respectable lodgings in Falmouth, in Upper Street, with Mrs Trewhella, but don’t tell anyone, will you, Cici? Not a soul.

I took a deep breath. Arbella’s elopement was all the courage I needed. If she could escape, so could I.

Chapter Three

Polcarrow Thursday 7th November 1793, 5:30 p.m.

The footman looked incredulous but he took the boy in his arms, gaping in disbelief.

‘See to him straightaway, if you don’t mind. He needs urgent attention.’ Behind him, the blonde woman was running down the stairs clutching a pile of clothes. Bobbing a petrified curtsy, she hurried away.

‘Could you take me to Sir James?’ I called after her.

She stopped abruptly. ‘Sir James’s not at home, m’lady,’ she replied with wide-open eyes.

I crossed the polished black and white marble floor, and lowered my voice. ‘We both know he’s at home and we need to be quick if we’re going to catch the tide.’ She went as white as a sheet but made no protest, turning instead down the panelled corridor. I followed close behind, stopping outside an ornately carved door. ‘Tell him Miss Cavendish would like a word.’

The remaining colour drained from her face. ‘Miss Celia Cavendish?’

‘Yes,’ I replied.

The house was certainly ancient, Sir James’ study particularly dark. Dense wooden panels lined the walls, an assortment of ruffed ancestors peering down from their frames. A large fireplace dominated the furthest wall and heavy beams crossed the low ceiling. The furniture was solid, intricately carved, the flagstones highly polished. Only the drapes looked new. Sir James looked up.

‘Miss Cavendish! What brings you bursting in like this?’ For such a young man, James Polcarrow could look stern at the best of times; when he was angry, he looked petrifying.

‘Forgive me, Sir James. I’ve just witnessed Viscount Vallenforth whip a boy half to death and I’ve brought him here – for his safety.’

‘For his safety?’ His eyes sharpened beneath his frown.

‘Well, mine as well, I suppose.’

Lady Polcarrow was by his side, watching me. She was breathtakingly beautiful – perfect oval face, high cheekbones, her piercingly intelligent eyes somehow magnetic in their power. Her chestnut hair was coiled beneath her lace cap, her gown definitely Marseilles silk. She had risen so far, but with looks like that, it was hardly surprising. We knew one another only slightly from when she worked at the dressmaker’s, but I liked her very much and felt sure I could trust her.

‘I imagine Viscount Vallenforth does that rather a lot,’ she said with evident distaste.

‘I can’t go back, Lady Polcarrow.’

‘How can we help?’ Her voice was cautious, wariness darkening those beautiful eyes.

‘Take me with you to Falmouth,’ I said, watching their astonished faces. ‘Forgive me…I know it was wrong to listen – I was searching for a groom and heard you talking. I didn’t mean to eavesdrop but I heard everything. As it happens, it quite suits my plans. When we get to Falmouth, I’ll leave you in peace and your secret will remain safe.’

Sir James looked furious. ‘Miss Cavendish, if you think for one moment—’

‘No, wait, James…’ Rose Polcarrow put her hand on her husband’s arm. ‘Miss Cavendish must need our help very badly, or she’d never suggest such an idea. How’s the boy?’

‘Thrashed to within an inch of his life. I can’t go back, Lady Polcarrow – if I do, my parents will take no notice of my pleas. They won’t let me break my engagement – I need leverage, some kind of bargaining power.’

Lady Polcarrow nodded but James Polcarrow remained thunderous, his handsome face scowling at me with dislike. ‘Miss Cavendish, I’ll take no part in your running away.’

‘But she’s welcome to stay here, isn’t she, James?’ Rose Polcarrow clearly understood. She understood and she cared. ‘We can’t do anything now, but when we come back, we’ll try to help…only stay here, don’t go to Falmouth.’

She meant well, but if they were in Falmouth they could not keep me from my parents. It would only be a matter of time before Father barged his way in and dragged me back. Arbella had known her only hope had been to run. ‘It’s very kind of you, Lady Polcarrow, but my parents will only listen to me if they fear scandal. I have to go to Falmouth and if you don’t take me, I’ll make my own way.’

‘Where in Falmouth?’ barked Sir James.

‘I’m afraid I’m sworn to secrecy.’

‘You’re going to Arbella! How could you be so foolish?’

‘Please Sir James, I don’t do this lightly. I know the consequences but I believe I’ll be safe with Arbella and her husband – I have their address.’

Sir James shrugged his shoulders. ‘It’s your choice, Miss Cavendish. Ruin your reputation along with your cousin’s – it’s no concern of mine.’ He turned to Joseph. ‘Move the bookcase, if you don’t mind and when we’re through, put it back exactly as it was. Jenna, if you could order our supper on trays and tell everyone we’ve gone to our room…tell them we woke unwell and you’ve sent for the doctor. We may be gone several days – four, maybe five.’

Jenna nodded. She was sifting through the pile of clothes, holding up one garment, then another. They were working men’s clothes, coarse jackets and breeches. A pair of boots stood on the floor, two large hats ready on the table and I stared in disbelief, hardly believing my eyes. Jenna was unfastening Lady Polcarrow’s laces, Sir James already pulling off his coat and I turned quickly away, staring at the huge wooden globe in front of me.

‘Are you ready, Miss Cavendish?’ The beautifully elegant Rose Polcarrow had disappeared and in her place stood a tall, gangling youth wearing brown corduroy breeches and a worsted-wool jacket. Her hair was scraped back beneath the large hat, her boots scuffed and covered in mud. Gone, too, were Sir James’ finely tailored clothes. A sailor stood in his place, wearing a dark blue jacket and baggy breeches, a red scarf tied around his neck. I stared at them, my heart racing.

‘Take those diamonds off your ears, Miss Cavendish, and if you value your life, get that ring off your finger. Put them in your purse. Where’s your cloak?’ James Polcarrow opened the top drawer of his desk and began filling a leather pouch with coins.

‘I don’t have a purse and the boy’s wrapped in my cloak.’

‘Then take this,’ he said, sliding the purse across the desk towards me.

‘Thank you. That’s very generous. I’ll pay you straight back.’

‘It’s not generous, it’s worth nothing – just pennies and half-pennies but it’s what you’ll need. Hide your jewellery down your bodice and wear this.’ He reached for a cloak folded across the back of a chair. ‘Keep hooded at all times. No-one must know you’re on my boat.’

I wrapped the cloak around me. It was black and coarse but covered me completely. I lifted the hood to hide my face and turned at the sound of scraping. Joseph had his back against a bookcase and was heaving it slowly away from the dark wooden panelling.

‘Thank you Joseph.’ Sir James strode across the hall, buckling up the strap of his leather belt. A large bag lay slung over his shoulder, a pouch hung from his waist. ‘The catch is here – this bit that looks like a knot. Press that and the spring releases.’

Joseph pressed the knot and a panel sprung open, a dark entrance gaping in front of us. It was about three feet across and as black as a grave. Rose was watching me. ‘It leads down to the sea – to the rocks beneath the rope-walk, but James won’t let you see where it comes out. He’ll blindfold you at the entrance.’

‘I don’t mind,’ I said, my heart hammering.

‘It’s cramped and dirty. Water drips from the rocks and there are deep pools of water – your boots’ll get ruined.’

‘I don’t mind,’ I repeated.

‘The lantern’s likely to go out and bats might fly down at you.’

If she thought she was putting me off, she was not succeeding. ‘I’ll manage.’

‘Of course you will,’ she replied, smiling. She handed me a lantern. ‘Just stay very close.’

I crouched at the tunnel’s entrance, catching Joseph’s eye. ‘My horse’s tethered by the coach-house. Could you stable her tonight and return her to Pendenning? Perhaps you could say you found her wandering?’

A voice echoed through the tunnel, ‘Keep close, Miss Cavendish.’

The tunnel smelt damp, airless. It was icily cold, the walls solid stone, the floor roughly hewn flagstones. We were going down, the tunnel widening to the width of two men. I leant forward, bending almost double to avoid the rocks jutting down from above. A drop splashed my cheek and I stopped just in time. A vast pool of water glistened ahead of me; black, stagnant, smelling of damp earth and putrid mud.

I put down my lantern and pulled up my skirts, hitching them high above my knees. It felt strangely wonderful. No-one was watching me.

For the first time in my life, I was free.

Chapter Four

Rose undid the red scarf from around my eyes and smiled, handing it quickly back to her husband. The wind was blowing against our cheeks, the waves surging against the rocks we were standing on. Everywhere was wet and slimy, covered in cockles, and it was hard not to slip. Rose seemed so sure-footed, Sir James dragging a rowing boat behind him. At the water’s edge, he pushed the boat into the foaming waves. ‘Get in, Miss Cavendish – sit in the bow.’ I held my breath, summoning my courage. As the boat tipped, I gripped the sides, edging forward as Rose and Sir James got in behind me.

‘We’re away,’ shouted Rose as Sir James pulled on the oars, skimming through the white foam, the tip of rocks just visible beneath us. Seaweed swirled round the boat, swaying in a black mass. I could see barnacles, limpets, an encrusted chain. The salty air smelt so good. It was so fresh, so raw, a million worlds away from the stuffy rooms I hated so much.

We were at the widest stretch of the river, pointing east towards Porthruan. Both harbours were busy. Ships lay three abreast along the harbour walls, their masts rocking in the swell of the waves. Vast pulleys stretched high into the air, hoisting sacks onto the decks and into the holds. Men were rolling barrels along the quayside; mules were waiting, their carts piled high with produce. The spray was wetting my cloak, soaking my hood. My boots were wet and muddy, my hem just saved from ruin, yet I felt like pinching myself. I was living, not watching. For once, doing, not dreaming. Across the water, the church bells chimed half past six.

Sir James pulled hard on the oars, his face streaked with spray. ‘The tide’s on the turn. Where’s L’Aigrette anchored, Rose?’

‘This side…behind that brig. I hope she hasn’t left.’ Her words were lost to the wind.

Sir James heaved on the oars, his pace quickening. The waves were mounting, our boat low in the water. Huge black hulls towered above us, lanterns hanging from their sterns, lights dancing across their decks. It was clearly time to leave. Men were climbing the rigging, heaving on ropes. Shouts were ringing across the darkness, sails unfurling, anchors rising from the water.

Sir James’ words were clipped with exertion. ‘When we’re aboard…don’t use our names. Captain Lefèvre will recognise us but the crew mustn’t know who we are. Can you see her, Rose?

‘She’s there – she hasn’t left.’

I looked up, my heart sinking. The boat we were rowing to seemed so small – only a tiny one-masted cutter, not a ship at all. I could hardly believe it. ‘Not that one, surely?’

Rose smiled. ‘Wait till you sail on her.’ We were alongside her now, her black hull glistening in the water beside us. Sir James lifted the oars and grabbed the hull.

‘What the hell?’ came a voice from the deck.

‘I’ve urgent business with Captain Lefèvre,’ shouted Sir James.

A second man leant over the rail. ‘And that business is?’ He, too, sounded French and distinctly annoyed.

‘Captain Lefèvre, I need to speak to you.’The figure disappeared and a ladder slammed against the hull. It was made of rope, the wooden rungs secured by huge knots. Sir James caught the ladder and pulled it tight, the two boats knocking together in the considerable swell.

‘Go first,’ urged Rose. ‘Hold very tight as the rope can get slippery. Sir James will keep it steady.’ I pulled my hood over my head, grabbing the ladder tightly.

The sea looked ominously dark, the boats rising and falling at different times. The swell was lifting first one, then the other and it was hard to judge the timing. I put my foot on the bottom rung and held my breath. On the second rung, I felt my boot tug against my skirt and realised I had caught my hem. I tried kicking my foot free, but the corduroy was wet and clinging to my leg. I tried again. I had never done anything like this before. I had rowed the Thames at Richmond, but never dangled from a boat in open sea.

My only option was to tug my skirt free but the waves were swirling beneath me, and letting go with one hand much harder than I thought. The captain was watching from above, James Polcarrow standing in the boat below; both men must think me so foolish. Only Rose would understand how difficult it was, hauling yourself up a swaying ladder in a heavy riding dress. I pulled at my skirt but a large wave rolled beneath me, swinging me violently round, knocking me against the hull.

The captain swung himself over the side; one hand holding the ladder, the other reaching towards me. ‘Give me your hand,’ he said, leaning as far down as he could.

I would have reached up, but another, stronger, wave crashed the two boats together and I clung even tighter to the rope, scared to be thrown off balance. I was normally so fearless, but the waves were unpredictable, and the foaming black sea suddenly so terrifying. I looked up, preparing to reach out my hand, but Captain Lefèvre was already halfway down the ladder, his arm encircling my waist. His strong arm held me, his body safe behind me and I began kicking my foot free. At once, I heard his command. ‘Put your arms round my neck.’

His arm loosened from my waist and reached round my thighs, gripping me tightly and I could do nothing but comply. I slid my hands round his neck and felt myself lifted effortlessly up the ladder, pinned closely against his chest. At the top he swung me over the rail, holding me carefully until my feet touched the deck. I looked up. His eyes were searching the shadows beneath my hood and I turned swiftly away, pulling my cloak closely round me.

Though he could not see me, I saw him clearly. He was tall, fine-boned, his clean-shaven face browned by the sun. Wisps of brown hair blew across his face, the rest tied neatly in a bow behind his neck. His jacket was blue silk, well cut, made only for him. His breeches were leather, his boots highly polished. His movements were quick, decisive, his body at one with the swaying boat. Already he was helping Rose over the side. I saw him nod to Sir James but when he looked back at me, his eyes looked watchful.

‘This way, mademoiselle,’ he said. ‘Down this hatchway – but I’ll leave you to yourself, this time.’

The steps opened to a small kitchen, an iron stove standing at its centre, a black pipe leading to the deck above. Cooking utensils hung from large brass hooks and plates and pans lay neatly stowed behind carved wooden grilles. Bottles of wine lay cradled in a curved rack and lemons swung freely in a knotted rope. Rose and Sir James gave it barely a glance but I was struck by the beauty of the glass-fronted cabinets.

‘Go through, mademoiselle,’ he said, pointing the way.