Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Cornish

- Sprache: Englisch

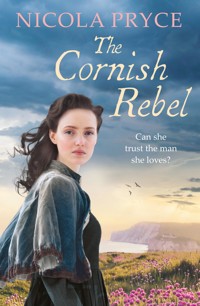

Cornwall, 1801. In the wake of her mother's death, Pandora Woodville is desperate to escape her domineering father and finally return to Cornwall. Posing as a widow, she safely makes it across the Atlantic, bright with the dream of working at her Aunt Harriet's school for young women. But as Pandora is soon to learn, the school is facing imminent closure after a series of sinister events threatened its reputation. Acclaimed chemist Benedict Aubyn has also recently returned to Cornwall, to take up a new role as Turnpike Trust Surveyor. Pandora's arrival has been a strange one, so she is grateful when he shows her kindness. As news of the school's ruin spreads around town, everyone seems to be after her aunt's estate. Now, Pandora and Aunt Harriet must do everything in their power to save the school, or risk losing everything. However, Pandora has another problem. She's falling for Benedict. But can she trust him, or is he simply looking after his own interests?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 612

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

NICOLA PRYCE trained as a nurse at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. She has always loved literature and completed an Open University degree in Humanities. She is a qualified adult literacy support volunteer and lives with her husband in the Blackdown Hills in Somerset. Together they sail the south coast of Cornwall in search of adventure.

Also by Nicola Pryce

Pengelly’s Daughter

The Captain’s Girl

The Cornish Dressmaker

The Cornish Lady

A Cornish Betrothal

The Cornish Captive

Published in paperback in Great Britain in 2023 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Nicola Pryce, 2023

The moral right of Nicola Pryce to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 919 7E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 920 3

Printed in Great Britain

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Ali and Chris Mitchell

Cast of Characters

FALMOUTH

ON BOARD THE BRIGATINE JANE O’LEARY

Mary James

Master’s wife

Pandora Woodville

Passenger from Philadelphia

Captain James

Ship’s Master

THE QUAYSIDE INN

Benedict Aubyn

Turnpike Trust employee

John Loudon McAdam

Road builder

Marcus Cartwright

Turnpike Trust clerk

RESTRONGUET CREEK

ST FEOCA MANOR: SCHOOL FOR YOUNG LADIES.

Founded 1774

Grace Elliot

Pupil, now teacher

Annie Rowe

Retired housekeeper

Richard Compton

Prospective inheritor of St Feoca Manor

FEOCA SCHOOL GATEHOUSE

George Penrose

Groundsman for St Feoca School

Susan Penrose

Housekeeper for St Feoca School

Kate Penrose

Daughter

DEVORAN FARM (OWNED BY THE SCHOOL)

Samuel Devoran

Farmer

Jane Devoran

Wife

Gwen

Daughter

Sophie

Daughter

FEOCA MILL (OWNED BY THE SCHOOL)

Jacob Carter

Miller

Martha Carter

Wife

Mollie

Daughter

ST FEOCA SCHOOL GOVERNORS

Lady Clarissa Carew

Philanthropist

Reverend Opus Penhaligan

Retired clergyman

Mrs Mary Lilly

Philanthropist

Mrs Angelica Trevelyan

Ship company owner and former pupil

TREGENNA HALL: NEIGHBOURING ESTATE

Sir Anthony Ferris

Wealthy landowner

Cador Ferris

Eldest son and heir

Olwyn Ferris

Daughter

TRURO

TURNPIKE TRUST MEETING

Lord Entworth

Turnpike Trust Chairman

Marcus Cartwright

Clerk to the Turnpike Trust

Henry Trevelyan

Ship company owner

Jonathan Banks

Land agent

Major Trelawney

Local militia

Francis Polcarrow

Trainee attorney

Meredith Trelawney

Friend of Benedict Aubyn

Esse Quam Videri

To be, rather than seem to be

The Hero’s Journey

Stage One: The Call to Adventure

Stage Two: The Supreme Ordeal

Stage Three: Unification

Stage Four: The Hero’s Return

PROPOSED TURNPIKE ROADFROM TRURO TO FALMOUTH

Required with immediate effect: a teacher, or a lady who has held a position as governess, is invited to apply for a position in St Feoca School for Young Ladies.

The applicant must be educated to a high degree, be in her thirties, and be steadfast in her support of female education.

Salary and conditions of service will be discussed at interview.

All applicants to write to Lady Clarissa Carew of Trenwyn House.

Stage One

THE CALL TO ADVENTURE

Chapter One

On board Jane O’Leary, Falmouth Sunday 22nd March 1801, 12 p.m.

The ship was rising and falling, the wind tugging at our cloaks. ‘There – on that promontory – that’s Pendennis Castle.’ Mary James handed me the telescope and an outline of turrets and battlements sharpened into focus.

‘The soldiers have got their telescopes trained on us.’

Around us, angry white crests peaked and broke; a fresh burst of spray carried on the wind and Mary clasped her cloak tighter. ‘They’ll be expecting us. Mr Trevelyan’s very particular about letting them know we’re coming. They’ll recognise our flags. One shows we’re from America and one shows we’re carrying grain.’

This was Falmouth, England, the home of my childhood. Tears welled in my eyes. I was a child again, gripping my mother’s hand, staring back at the same squat battlements: an inconsolable child of six, devastated to be leaving St Feoca and the family I loved.

In her early thirties, Mary James was far stronger than she looked. ‘I shall miss our talks, Clara. I’ve loved your company.’ Slim and agile, she could haul a rope as well as any man. Her voice drifting on the wind, she slipped her arm through mine. ‘I love your tales of gods and goddesses – and all your talk of grand receptions and fancy dinners – the concerts, and fetes in Government House. It’s as if I’ve been there – that I’ve been using fine bone china and dining with naval officers in their gold brocade.’

I smiled with what I hoped looked like conviction and she smiled back. ‘But you know the best part? The best part is you being friends with the Governor’s daughters. I’ve not been to Grenada or Dominica, but it’s like I’ve been wearing fine silk gowns and going to balls and soirees.’

‘And I’ve learned all about the wind and currents, and how to set sails. You and Captain James have been so good to me. I can’t thank you enough.’

Shouts echoed across the deck, the men hauling on the ropes. Above us, the sails tightened, the bow heading inland to the safe waters of Carrick Roads. Before long, Pendennis Castle would rise to our left, St Mawes Castle to our right.

Captain James came to my side. ‘I said I’d get you here, and here we are. It’s been a good passage, Mrs Marshall. You must sail with us again. Not an enemy ship in sight. I’ve never known the winds so favourable.’ A thick-set man with a weather-beaten face, he put his telescope to his eye. ‘No doubt it’s all down to your gods and goddesses. Had a word with your friend, Poseidon, did you?’

‘Maybe the odd word!’

‘We’ll get extra for arriving early. Mr Trevelyan’s good like that.’ He scanned the entrance to the harbour. ‘They’ll make us anchor. We’re the first grain ship from America for several years and they’ll want to check we’re not carrying hessian fly. There’s urgent need for this corn. The harvests failed again last year – there’s severe shortages. I gather there’s been food riots. Let’s hope we don’t meet any trouble.’

‘Trouble, Captain James?’

‘As to who gets to distribute the wheat. The navy want it, the army want it, and the people want it.’

A mist hung above the town, the waves calmer now we were in sheltered water. Seagulls circled above us, a smell of manure drifting across the water. Just visible, a church tower rose above a cluster of granite roofs. Nothing but grey: grey houses, grey sky, grey sea. No reflections dancing on an azure bay, no bleached beaches, no fiery hibiscus flowers the size of saucers; no scorching sun, no oppressive heat. No one demanding money from me. Clutching my gold locket, I breathed in the air of my childhood. We’re home, Mama. We’re home.

Captain James scanned the quayside with his telescope. ‘We should make one hundred and eighty shillings a quarter.’ A green and red flag fluttered from the wharf and he examined it carefully. ‘Yes . . . there it is. We’ve got the signal to anchor.’ Swinging round, he shouted, ‘Starboard thirty degrees. We’ll anchor in Flushing, behind that naval frigate.’

Mary’s smile was apologetic. ‘I’m so sorry about your luggage, Clara. There are some very unscrupulous people on the quays in Philadelphia – we should never have let it happen.’

‘No . . . please don’t blame yourself. I should have guarded it better, but trunks and clothes can be replaced. Papa can bring some more clothes when he comes.’ I dived beneath my cloak and reached for my letter. ‘I’ve written all about how very kind you’ve been, and what a comfortable crossing we’ve had. Will you post this to him when you get back?’

‘Of course I will.’ She read the address. ‘Reverend J. S. Turner, Headmaster’s House, Germantown Academy, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.’

I hoped my smile looked convincing. ‘The Academy couldn’t do without him. He’s very well thought of. He has a doctorate in Divinity and the boys love him. They converse with him in Greek and Latin. He’s an inspiring teacher as well as a brilliant scholar.’

Falmouth looked smaller than I remembered, or did I remember it at all? It was hard to know what my memories were and what I had been told. Mama hardly ever mentioned Falmouth but her tone always lifted when she spoke of her parents. Her smile would broaden, her eyes fill with love, as she recounted stories of Grandfather’s treasure hunts, his love of riddles, his knowledge of flowers. Her memories had acted like light in the darkness, a beacon reassuring me of home. But there was always a stumble when she mentioned her beloved elder sister: always a catch to her voice. What would Aunt Hetty think of you slouching like that? Back straight – never forget you come from English gentry.

Mary must have read my mind. ‘Not quite Philadelphia, is it? But don’t judge it from today’s weather. Cornwall’s very beautiful. In the sun, the houses in Truro shine like gold.’ Her eyes softened. ‘I hope we’ve been of some comfort to you, Clara. We so feel for your loss.’

I felt for the gold band on my third finger. ‘You’ve brought me great comfort. Thank you.’ Far greater comfort than she would ever know.

‘So you’re to teach in your aunt’s school? How will you get there?’

Mama’s voice had been a whisper: The ferry for the Passage Inn leaves from Falmouth Quay. From there, take another ferry across Restronguet Creek. The gatehouse is on the water’s edge. You won’t get lost. Tell the ferryman Aunt Hetty will pay.

I tried to sound strong. ‘I need to take the coach to Penzance. My aunt’s school overlooks the sea. Father tells me it’s very straightforward and easy to find.’

Inching forward under two small sails, Captain James rechecked the chart. A row of smart houses lined the quay, a group of men watching us from behind a stack of lobster pots. ‘What’s our depth?’

One of the crew was bending over the bow with a knotted chain. ‘Five fathoms . . . four fathoms . . .’

‘Drop anchor.’ The anchor splashed and Captain James took the wheel. The stern swung round and started pulling against the rope. A crowd was gathering, children watching from the window of a grand house. ‘Seems to be holding. Good.’ Hardly a timber creaked, a stillness on the ship we had not felt for six weeks.

Across the water the houses of Falmouth were hardly distinguishable in the grey mist. The sound of oars carried across the water: a rowing boat was splashing towards us. ‘Here are the Excise men. They’ll need to see your papers. They’ll check everyone’s health records and if there’s any sign of fever they’ll stop us unloading.’

Mary reached for my gloved hands. ‘Fortunately, that’s not the case. I shall miss you, Clara.’ There was kindness in her eyes. ‘You’re very lovely, my dear. I’m sure you’ll find someone else to love as dearly as you loved Mr Marshall.’

‘Thank you, Mary.’ With her holding my hands, I could not cross my fingers.

She reached up to prevent a rope from swinging too near my face. ‘Why not collect your belongings and we’ll ask them to clear you first? Jack can take you ashore once your papers are cleared. It would be a shame if you just missed the coach.’

I clutched my bag, my fear subsiding. My papers were in order – Clara Marshall, born 1780, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. No one had noticed the 1730 had been changed to 1780. The fine drizzle was strengthening to steady rain and I pulled my hood further over my bonnet. Jack’s rowing was strong, the water calm, the inner harbour of Falmouth full of ships. Placing the oars in the bottom of the boat he leaned over to catch the chain. The boat tipped and I grabbed the sides. ‘Mind these steps, Mrs Marshall, they’ll be slippery. Best hold the rope. What a downpour!’

I was home. Home. A huge wooden crane towered above us, a group of men unloading the hold of a ship. Harnessed oxen waited in a line, a man shouting instructions. Gripping my skirt, I climbed up the steps to the quayside, the stench of fish guts turning my stomach. An empty cart rumbled past and I only just leapt out of its way. Standing on the cobbles, I felt light-headed, almost dizzy.

‘You all right, Mrs Marshall? Everything swaying? First you need to find your sea legs, then you need to find your land legs! It’ll pass.’ He looked around, my bag in his hand. ‘Mrs James says to find the coaching inn. Where’s that, d’you think?’

Puddles were forming on the cobbles around us, yet I had good sturdy boots and a thick woollen cloak. I kept my hood pulled low. ‘Jack . . . please don’t wait on my account. They’ll need you back on the ship – I can ask these people where to go. Thank you dearly – but I’ll be fine.’ A notice caught my attention: the paint was peeling, the board hanging at an angle but it was exactly what I needed to find – Ferry to Passage House Inn. Every two hours.

‘No, Mrs Marshall, I’ll see you to the coaching inn.’ Jack readjusted his collar against the driving rain. ‘We’ll take shelter beneath that overhang – looks like some sort of office. They can tell us where to go.’ Hurrying along the wet cobbles, I glanced at the dilapidated sign. The writing was only just visible. Ten o’clock, then every two hours. Last ferry eight o’clock. The church bells had just sounded half past two: I had an hour and a half to wait.

Suddenly my shoulder was wrenched and I stumbled forward. A man reached out, trying to steady my fall. ‘I’m so sorry. Are you all right? I didn’t see you under my umbrella. It was very clumsy of me.’ He was quietly spoken, full of remorse.

‘No, it was my fault. I had my hood too low and my head down. I didn’t see you.’

Drawing me under the overhang, he kept his umbrella above me. ‘Are you hurt? Only that was quite a jolt.’

The rain from my hood dripped onto my cheeks. ‘No, I’m fine.’

Jack squeezed into the shelter next to us. ‘First time in England, and here’s the rain they tell you about! Are you all right, Mrs Marshall? That was quite a bump.’ Flattening himself against the wall, he raised his hat. ‘I wonder, sir, if you know where the Penzance coach leaves?’

The man looked to be in his late twenties. He stood tall, if a little slight of build. His cheeks were gaunt, a furrow between his brows. There was mud on the hem of his coat, his boots scuffed, yet his voice was educated. ‘Yes, from the Coach and Horses. I’m going there now.’ He wore a heavy overcoat, buttoned to the neck, his umbrella clasped between thick leather gloves. Holding the handle towards me, he smiled a half-smile. ‘Please, use my umbrella. The inn’s just round the corner – I’ll be happy to show you.’ Pulling up his collar, he bowed. ‘Benedict Aubyn, at your service.’

‘Thank you, Mr Aubyn, you’re very kind.’ Turning to Jack, I tried to hide my relief. ‘Mr Aubyn will show me the way and if I’ve missed the coach, I’ll come straight back to the ship.’

Mr Aubyn followed my gaze. ‘You’ve come off that grain ship? I must say she’s a welcome sight.’ He seemed strangely shy, a true English gentleman. Just like you told me, Mama.

‘We’ve come from Philadelphia – though Cornwall is my real home.’

The strange half-smile again, a sudden lightening in his eyes. ‘Welcome home, Mrs Marshall. I’m sorry about the weather.’ Benedict Aubyn stepped into the rain. ‘And you haven’t missed the coach. It leaves at four, but you’ll need to book your seat. I suggest we go now – before that black cloud drenches us further. May I take your bag?’

I knew to keep a tight hold of it. ‘Thank you, but it’s no weight at all.’

He looked around. ‘You have other luggage?’

Jack shook his head. ‘Mrs Marshall’s a widow. She got taken advantage of. All her luggage was stolen.’

A flash of anger crossed his eyes. ‘How despicable. Well, let me assure you, Mrs Marshall is safe with me. I shall escort her straight to the inn where she can get warm and dry.’ Jack seemed to hesitate, but as the rain was building he nodded. Mr Aubyn pointed up the street. ‘Shall we go now before this cart blocks our way?’ Stepping into the road, he bowed to Jack. ‘Good day, sir. A safe passage home.’

We turned the bend, and I swung round. Jack was watching and I waved goodbye, or so Benedict Aubyn must think. I had to memorise the way back.

Chapter Two

Everywhere, people were running to get out of the rain. Busier on the ground than it looked from the sea, Falmouth was crowded, the narrow streets twisting and turning, the rooftops almost meeting above us. I was used to straight, broad streets with wide pavements, not the ancient thatches on some houses, the beams on others. People’s accents sounded strange, even the church bells sounded different. We joined a long street and headed up the hill. Brick buildings with brass plates and polished front steps lined the pavement: a shop selling bonnets, another selling portmanteaus. A dressmaker, then a milliner’s shop, the smell of baking drifting across the street. Boys were wheeling barrows, a knife grinder busy beneath an arch.

Benedict Aubyn stayed by my side, stepping into the road when the pavement narrowed. Alleys led up the hill to our left but our way was forward, towards the main square with a horse trough at its centre. ‘There – across the square.’ Benedict Aubyn pointed towards a busy inn. Through the arch, stable lads were sweeping up horse dung, chickens squawking, the ostler shouting instructions. The rain dripping from his hat, Benedict pointed once again. ‘We need to go round the side to buy tickets.’

The ticket seller was behind a polished counter, the times of coaches chalked onto a blackboard above him. Handing him back his umbrella, I tried to hide my panic. ‘Thank you, Mr Aubyn – I’m afraid you’ve got rather wet on my account.’

The same slight half-smile, this time with a downward glance. ‘It’s of no consequence.’ Taking off his hat, he closed the umbrella, shaking it through the door on to the pavement outside. The woman in front of us was handing over her money and my fear spiralled. Benedict Aubyn was clearly not leaving.

‘Please don’t let me keep you. I’ll be fine, now. Thank you.’

His hat removed, his brown hair looked slightly dishevelled. Slightly too long, and slightly too curly, he drew it from across his forehead. ‘I’m early for a meeting – the least I can do is see you get your ticket.’ Through an arch, the taproom looked to be bursting, the voices deafening. ‘Then I’ll show you to a private area where you can wait in peace.’

Without his hat, his eyes looked slightly too narrow, his nose slightly too long. His forehead was furrowed, his cheeks even more gaunt. The woman in front of us was putting her tickets in her purse and Benedict Aubyn stepped forward. ‘One ticket for Penzance – inside, if you please.’ He turned, the same shy kindness in his eyes. ‘They’ll announce its departure in the inn, but best to be ready at least ten minutes before.’

‘That’ll be three shillings.’ The ticket seller did not look up. Adjusting his glasses, he started writing in the ledger. ‘Name please.’

A knot twisted my stomach. ‘Maybe, I won’t go today. Maybe, I’ll go back to the ship and leave tomorrow when it isn’t raining.’ I must have been blushing. I know I was stammering. I was usually so good at lying.

Benedict Aubyn was clearly perplexed. ‘But it’s very likely to rain again tomorrow – once this rain sets in it can rain all week!’ He stopped, as if with sudden understanding. Reaching inside his pocket, he drew out his wallet. ‘The name’s Mrs Marshall.’ He kept his eyes on the ticket seller.

My blush deepened. ‘No . . . please . . . I can’t accept this.’

‘All your luggage stolen, and straight from Philadelphia? You’ve no English money, have you, Mrs Marshall? In which case, it’s my pleasure to help.’ Handing me the ticket, he smiled his shy half-smile, again with the same downward glance. ‘Follow me – I’m afraid it’s going to be a bit of a crush.’ He led the way through the crowded taproom, his voice rising. ‘May we come through? Excuse me, if we can just pass?’ Inching ahead, we began making progress through the dripping coats. ‘Looks like everyone’s come in to get out of this rain.’

Gripping my bag, the crush was considerable. Elbows jolted me, the haze of tobacco smoke stinging my eyes. Heavy beams crossed the low ceiling, a huge fireplace at one side, groups of men sitting on benches beneath the small leaded windows on the other. The innkeeper was serving ale from a barrel, aproned girls weaving their pewter jugs through the crowd. Benedict reached for my arm. ‘It’s just through here.’

He pushed open a door to a murmur of men’s voices, too soft to distinguish what was being said. Elaborate oak screens partitioned the room into separate stalls and with each enclave affording much needed privacy important conversations were clearly taking place. Like the private pews in churches: like Grandfather’s church. A memory flashed of me hiding beneath the wooden screen as Grandfather preached from the lectern above.

‘This one’s free.’ Benedict stood back to let me pass. ‘The cubicles can be booked for private meetings. Some like to do business in the taproom but you can’t hear yourself think in there.’ He looked round. ‘There’s the clock – so you’ll know when to leave. You’ll be safe here.’

Diffuse light filtered through the rain-splashed windows, a fire burning in the grate. A group of women sat in high-backed chairs by the fireplace, the surrounding murmur of voices sometimes animated, but always muffled. I braced myself. Now he would make his move. Now, in the privacy of the cubicle, just like all the other gentlemen in Government House. Yet he turned to go.

‘I’ll see you get some ale.’ No sudden push against the oak panelling, no groping for my breast. No hand sliding beneath my cloak and up my thigh. No leer as if I should expect no less. Just a flash of his sad half-smile and a downward glance. ‘Goodbye, Mrs Marshall. I hope you have a comfortable journey. Penzance is a very interesting town. You have family there?’

Thrown by his sincerity, my cheeks burned like fire. ‘Yes – my family. I’m going home.’

‘I’m sure they will be overjoyed to see you. Good day, Mrs Marshall.’

‘Thank you for your kindness.’ Guilt ripped through me. He needed nourishment. He should have used the money for a meal.

‘Not at all.’ There was sadness in his shrug, a look of loss as he turned away.

The serving girl bringing the ale assured me I had nothing to pay and my guilt deepened. The men in a cubicle nearer the door were leaving and, as it would be easier to see the clock, I decided to take their place. Settling myself, the door opened and through a small crack in the screen, I saw Benedict Aubyn re-enter the room with two men. He took down the piece of paper pinned to the cubicle next to mine. ‘We’re in here – I’ve booked for an hour. Shall I order you something to drink?’

The taller of his companions shook his head. ‘I’ve had sufficient, thank you.’ He had a Scottish accent. Sombrely but smartly dressed, he was in his late forties. Beneath his wide hat he had heavy brows, a clean-shaven chin and a long nose. His coat dripping in one hand, he grasped a leather bag in the other. ‘Unless you’d like some, Mr Cartwright?’

The second man shook his head. ‘I’ve plans to dine later.’ Short and stout, his face florid, he seemed to be having difficulty squeezing along the bench. His high-pitched voice grew terse. ‘We’re not here on a fool’s errand, I hope, Mr McAdam?’

The Scottish man hung up his coat and slipped along the bench opposite. His case snapped open, and I heard the rustle of papers. ‘I believe not, Mr Cartwright.’ Silence followed, just the swift movements of Benedict Aubyn as he settled himself on the other side of the screen.

Curiosity is not a crime, Mama – curiosity is how I found out. Following my father was one thing, but eavesdropping on a kind and generous stranger? I sat rigid, knowing it was wrong, yet I could not help myself. Resting my head against the warped panel, I pressed my ear against the black wood. It was not my fault it was riddled with cracks and holes. Not my fault I could overhear their lowered voices.

Chapter Three

Benedict Aubyn cleared his throat. ‘I’ve decided I’ll take the position. With added considerations.’

I heard a slow exhale of breath, then the high-pitched voice. ‘Excellent. You’re far the best candidate. We want you, Mr Aubyn . . . here are our terms. You’ve proved yourself a shrewd negotiator – and the Trust admire you for that. They’re offering forty guineas per annum plus expenses. Read this at your leisure . . . it’s a two-year contract – though you’ll see the first six weeks are considered probation. Prove you can do the job, and there’ll be rich rewards.’

I hardly recognised Benedict Aubyn’s voice, yet he was sitting right behind me. No longer charming, he sounded hard-nosed, callous. ‘Rich rewards is what I’m after, Mr Cartwright.’

‘Indeed, Mr Aubyn. Rich rewards are what we’re all after. The Turnpike Trust are men of rank who expect results . . . if you understand what I mean?’

‘I do understand you, Mr Cartwright. Which is why the considerations I have set out here must be met. I want fifty guineas per annum, and ten per cent of every land deal I negotiate. Plus ten per cent of every mile I save . . . a free pass through all the tollgates . . . and ten per cent of every advantageous contract I pass your way.’

Papers slid across the table, a deep intake of breath, a pause, then the high-pitched voice edged with anger. ‘These terms cannot be met. They said you’d be amenable, Mr Aubyn. Not arrogant and self-seeking. I can assure you these terms will be found unacceptable. Mr McAdam, you’ve wasted my time. Your protégé has overreached himself.’

The Scottish voice again, soft, calm. ‘My protégé is the best there is. If the Truro to Falmouth Turnpike Trust can’t agree to his terms there are other trusts lining up to employ him. No surveyor knows the land like Mr Aubyn, and not to employ him would be a false economy. I’ve seen his plans. Even allowing for his ten per cent, your sponsors will reap vast rewards.’

‘What plans? Let me see them?’

A soft laugh, but the same hard edge to Benedict’s reply. ‘Only when I’m fully employed by your trust.’

The anger returned, and with it a note of sarcasm. ‘You’re not the man I was led to believe you to be. I was expecting a gentleman, sir.’

On the other side of the screen, Benedict Aubyn’s voice remained steady. ‘That’s as it may be, Mr Cartwright. I may not be as malleable as you expect but I have the skills you need. And I come at a price.’

The Scottish voice again, smoothing the waters. ‘I’ll not be in Falmouth for much longer. Within six months I take up my position as surveyor to the Bristol Turnpike Trust. I’ve taught Mr Aubyn everything I know about road building. He’s the man you want. In fact, I’d go as far as to say he’s the man you need. Pay him what he asks and you’ll not regret it.’

Outside the rain was lessening, though drips still clung to the window. I hardly dared to move but edged forward to see the clock. Another fifteen minutes and I would leave. No sound came from the other cubicle, and I supposed Benedict Aubyn to be reading the contract. A commotion made me look up: the women from the fireplace were leaving.

‘That looks in order. I may not seem a gentleman to you, Mr Cartwright, but I give you my word I shall deliver exactly what the Turnpike Trust ask of me – an efficient route from Truro to Falmouth to link with the Penzance and Newlyn turnpike. Once my considerations are approved, I’ll bring my plans to the next meeting.’

‘Just sign the contract, Mr Aubyn. Your considerations will be approved.’

The women were picking up their luggage and preparing to leave. Perhaps I should slip out with them? Yet I pulled back, unable to resist looking through the small crack behind me. Benedict Aubyn was signing several papers, the stout man heaving himself along the bench, a deep scowl on his face. ‘Don’t let us regret this, Mr Aubyn.’

It was too late to leave. Benedict Aubyn rose to see the stout man to the door and I held my breath, desperate for him not to see me sitting so close. The Scottish man reached for his coat, smiling as Benedict shook his hand. ‘Thank you, John. I won’t let you down. You know what this means to me.’

‘I know all about growing expenses. Bairns have a habit of growing! Especially wee lasses with their frocks and ribbons!’ He paused, his voice softening. ‘You’ve done the right thing, Benedict. It’s not an easy decision, but it’s the right decision.’

‘The truth is, it’s the only decision.’

They were getting ready to leave and John McAdam’s voice turned serious. ‘You’re absolutely certain there are no obstacles? She sounds . . . well – let’s put it this way – I’ve heard she’s a prickly, middle-aged spinster rather set in her ways. She may not view your new route as progress.’

I held my ear against the crack. Benedict Aubyn’s voice was a whisper. ‘The word is she’s bankrupt. The school’s all but closed. There are no pupils left and her staff have been dismissed. My offer will be a godsend to her. I can’t see her putting up any objection at all.’

‘Get that land, and you’ll get access to the river.’

‘Indeed. Get access to the river and a new bridge will take twenty miles off the old road.’

There was a soft laugh. ‘Which means an improved access to Harcourt Quay. Your first lucrative land deal, Ben. I congratulate you. Rich rewards indeed.’

Distaste soured my mouth. He was not a gentleman at all. He was just like every man in Government House; just another greedy, manipulating, unscrupulous man who thought nothing of cheating some poor middle-aged woman out of her due.

‘How’s work progressing on the shore road? You should be finished soon.’ John McAdam was just on the other side of the screen, if he took two steps backwards he would know I had overheard everything.

Benedict Aubyn replaced his hat over his curls. ‘Going rather slowly but going well. I’m a stickler for your rules and they don’t like it. I’m insisting on a depth of six inches and all small stones. Followed by another six inches once that’s consolidated.’

‘Good man. And not one single stone over the size of a walnut?’

‘Not one single stone!’

John McAdam put his hand on Benedict Aubyn’s shoulder. ‘Remember, the stones must be broken sitting down – that’s the important consideration. A woman sitting on a straw mat by the side of the road can break more stones in a day than two men with pickaxes. Remember that.’

‘I will.’

Benedict Aubyn closed the door behind them, and I glanced to see if the rain had stopped. A woman was running across the courtyard, her cloak drawn round her. She was calling, obviously anxious to catch someone’s attention. Coming immediately to her side, Benedict Aubyn held his umbrella over her. She was clearly agitated, pleading with him, yet he kept shaking his head. I could almost read her lips, Please, Ben . . . please. His answer must have upset her as she held a handkerchief to her eyes.

Still he shook his head, his lips tight, both of them frowning, and I pulled back as he glanced round the courtyard. Reaching into his heavy coat he drew out his wallet, immediately pressing what could only be money into her hand. I saw her draw back, trying to refuse. Please don’t, Ben. Again and again. Please don’t. Yet he kept insisting she take his money. Reaching for her hands, he held the money firmly between her palms.

Silently, she bent her head and he put his arm around her shoulder, hurrying her out of the courtyard towards the road. The clock struck quarter to and I knew I must hurry.

The rain had lessened to a fine drizzle and I crossed the road, weaving my way between the on-comers, retracing my steps as fast as I could. The crane was still lifting barrels from the ship, the Jane O’Leary still swinging at anchor. A crowd had gathered outside the tavern, a fiddler playing. Across the dock, a row of people were waiting for the ferry and I heard the splash of oars. People at the top of the steps were picking up their baskets and I ran the last hundred yards, catching my breath as I stood staring down at the ferry I had imagined more times than I could remember.

‘Take care, mind yer step.’ The ferryman helped me on to the boat. It was wider than I expected, with rows of seats and a makeshift tarpaulin covering one end. A woman squeezed along as I approached.

‘Room fer one more under here.’ The tarpaulin barely covered us, but at least I would not be seen by Mary as we passed the Jane O’Leary. ‘That’s a big bag ye have there, my love. Been away?’

A lump caught my throat. ‘Yes.’

She smiled. ‘Well, yer home now, aren’t ye?’ Tears pooled in my eyes, a sudden desire to cry. I had been so brave, yet now I was on Mama’s ferry the enormity of my journey seemed almost too great. ‘Lord, bless ye, love! There’s no accountin’ fer life, is there?’

I could hardly speak. Aunt Hetty will adore you, and you will adore her. The ferryman’s coat dripped on to my cloak. ‘Tuppence please.’ He rattled the coins in the bag around his waist.

‘Miss Harriet Mitchell will pay. I believe you run a tally for those going to St Feoca School for Young Ladies?’

His scowl darkened, an immediate sneer of contempt. ‘Ye think I run a tally fer a woman with not a penny to her name? Tuppence, please, miss, or ye get off my boat.’

The other passengers were staring at me. A couple nudged each other, one making the sign of the cross. ‘Well . . . perhaps I can return with it tomorrow . . . when I have the tuppence from Miss Mitchell?’

‘When I have the tuppence?’ he mocked. ‘Like as well ye’ll be lost to the devil and never come back.’

Reeling from his tone, tears sprang to my eyes. ‘Please, sir . . .’

The woman next to me reached for her purse. ‘Here. Let the poor girl alone. Here . . . poor love. Take no note of him. Here . . . one good turn, an’ all that.’ She thrust two pennies into the ferryman’s hand. She was middle-aged, her hands raw. In her basket was an onion, two potatoes and something I did not recognise as a vegetable.

‘Thank you . . . I’ll repay you. Where do you live?’ A sudden thought made me reach for the leather bag hanging from my shoulder. ‘Or maybe you’d like one of these? Please choose one. I believe you could sell them for more than tuppence.’ Reaching into the purse, I pulled out some shells I had painted on the ship. Cupping them in my hand, I held them towards her. ‘Please take whichever one you like best.’

She gasped, her raw hand flying to her mouth. ‘But these are so good! Look . . . how can this be? A ship . . . and this one . . . ?’ She reached tentatively towards them as if the shells were too exquisite to touch. ‘A shoreline . . . an’ . . . flowers . . . an’ bless me, that’s a cat. Oh, I’d love that one, but ye must sell these, my love, not give them away.’

We had cast off from the harbour wall and were entering the wide waters of Carrick Roads. The wind was freshening, the waves building, and I pulled back beneath the rough canvas. ‘No . . . I insist.’ I handed her the oyster shell with the portrait of a black cat. ‘She’s Miss Mabel – a ship’s cat. I insist you keep her.’

‘Ye painted these, my love?’ She reached for the painting of the Jane O’Leary in full sail. ‘Look . . . see, everyone?’ Touching the arm of the man huddled beside her, she whispered, ‘Give the girl some money an’ ye can have this beautiful ship.’

Another man leaned forward, another and another. ‘Let’s take a look.’

Before I knew it she was cajoling the other passengers, smiling, winking, telling them they would regret not giving something so precious to their loved ones, and I smiled back, shrugging my shoulders, amazed by how well my shells were liked. The leather purse lay empty and she reached for my hand. ‘There ye are, my love, that’s three shillings and ninepence. Who’d have thought it? There’s no accountin’ for life.’

The drizzle was penetrating my cloak, the air cold, the water grey; black clouds formed a heavy band above us. I could hardly see Restronguet Creek, let alone recognise it; just the splashing of the oars, the swell of the waves, the water swilling round my feet. Just the smiles of my fellow passengers and the first money I had ever kept gripped tightly in my fist. ‘Does another ferry go across the creek?’ I asked.

She nodded. ‘Ye needs ring the bell – loudly mind, an’ vigorously! That usually brings him from his ale. See that thatch just coming into sight? That’s the Passage Inn. The Harcourt Ferry leaves from there. Ye can’t see much today, but it’s just across the water.’

The quay Mr McAdam had mentioned. I swung to face her. ‘Harcourt Quay?’

She shrugged, wrapping Miss Mabel in her grey handkerchief, tucking her safely down her bodice. ‘Aye, my love. Harcourt Quay. There’s a gatehouse through to St Feoca.’ Another woman crossed herself, another and another, and her eyes sharpened. ‘Come straight back if needs be. Ye’ve money enough fer a room in the inn now. Come back if needs be.’

Chapter Four

The fresh air did little to sober the ferryman. Scowling that he needed more than one passenger, he tripped and fell at my feet. ‘Need three at leashht.’

Only by paying him triple did he agree to take me, and I sat on the wet seat, gripping my bag. The light was fading, dusk falling, the fine drizzle soaking the seat beside me. As we drew closer, a grey tower loomed through the mist and my stomach tightened. ‘St Feoca Gatehouse?’

‘Was the larsht time I came.’ His cape dripped from his shoulders, his hat pulled low. ‘Shall I wait? Only, ye’re likely to come shtraight back.’ He seemed to think that was funny, his laugh turning to a hacking cough. Oil lamps were burning on the quayside, flickering against a warehouse, lighting up the sign Haye Copperhouse Merchants. Pulling the boat against the wall of vertical slates, he pointed to an iron ladder. ‘Up there.’

I ascended, the depth marked beside me . . . eight foot . . . nine foot . . . ten foot. I had no recollection of buildings, yet several lined the quay. Lamps were burning against their doors, the sign Carnon Streamworks and Chasewater Company just visible through the drizzle. The place looked deserted, no sign of life in any of the dwellings just the rain and mud, and huge piles of stones heaped on the cobbles. Picking my way around them, I started walking towards the gatehouse of the school.

It seemed immediately familiar. Built of grey stone, the arch towered above me. Solid and austere, it had four pointed windows beneath a row of crenellations and two windows on either side of heavy iron gates. It’s like a castle, Mama had whispered; they say it dates back to fourteen eighty.

The windows were shuttered and I knew I must bang on the door, yet a sudden memory made me catch my breath. I was a child again, clinging to the gates, the pain so vivid it cut me like a knife. Aunt Hetty was turning from me, crying, refusing to say goodbye. I was shouting after her, Father gripping my arm, dragging me away. I was trying to break free, desperate to run back to her and tell her not to cry. That I would return very soon. That I wanted to draw beetles and butterflies with her. That I wanted to study worms with her through her large magnifying glass.

I gripped the gate like I had done as a child of six. It rattled in my hands and I pushed it gently. It opened, and I started walking up the long drive. The ruts in the road looked newly repaired, the surface firm beneath my boots, though it was hard to see with no moon to guide me. It seemed strangely quiet, the trees lining the drive indistinguishable against the night sky. My memory was of oil lamps burning against the front door yet there was no sign of light. A brazier should be casting shadows against the ancient tower; I should be hearing laughter, the sound of singing from the chapel. The courtyard should be filled with running footsteps, the clatter of plates echoing across the cobbles from the kitchen.

Mama’s drawings had kept the school alive, kept my hopes alive. The buildings formed three sides of a square: the ancient stone monastery ahead of me, the tower and chapel to my right, the new wing with its large windows to my left. I remember the carriages sweeping round the yew tree to the front door before going through an arch to the courtyard behind. Yet the front door was closed, there was nothing, not even a light. No lamps were burning, just a faint smell of woodsmoke drifting through the drizzle.

Walking through the arch, the courtyard looked just as deserted. I stepped closer, peering across the cobbles. Light was filtering through the window of a downstairs room and I drew back, my black clothes concealing me from sight. The light was coming from the kitchen and I fought my sudden tears. A lamp was burning on the dresser, a fire roaring in the hearth. Two people were in the room, a grey-haired lady sitting in a rocking chair, and a young lady laying out a fine lace tablecloth. The young woman’s hair was the colour of ripe corn, her movements graceful, her back straight. She was laughing, smiling at the old lady. She seemed to be singing, picking up plates and placing them on the table. Standing back, she adjusted the crystal glasses and reached for a silver candelabra to place at the centre.

She turned round, and a stab of jealousy twisted my stomach. She was beautiful, like my mother – a delicate, English rose. Poised, elegant, she had all the attributes Mama wanted me to have and a terrible feeling of inadequacy flooded through me: Aunt Hetty would find me ungainly. She would think me too tall, too thin, my feet too big, my hands too large. Worse still, I had a snub nose, uncontrollable black curls and more freckles than were seemly. I had no accomplishments: I could not play a single note and had never learned any songs to please an after-dinner audience. Father made it quite clear – I was a woman men might employ as a governess but they would never seek to marry me.

The beautiful young woman looked down at her laid table. Smiling, she lit the candelabra and left the room. The grey-haired lady rose and walked stiffly to the range. Reaching for a cloth, she lifted a heavy iron skillet on to the table and my heart swelled. She was Annie, the housekeeper, though I hardly recognised her. She looked frail and anxious, her eyes darting to the window as if she thought someone might be watching her.

I took a step nearer, my heart jolting. The beautiful young woman was holding open the door, a lady entering – Aunt Hetty, my beloved Aunt Hetty, and I gripped my cloak. Two years older than Mama she looked poised, elegant, far younger than Mama and far taller too. I had forgotten her striking, rather formidable features, and memories came flooding back – the mischief in her smile when I brought her worms for us to study, her conspiratorial wink as we hid behind the gate so no one could see us. Not pretty like Mama, her looks had grown severe, her eyes sharper, more intelligent. Her hair was brown rather than fair, a band of a grey sweeping from her forehead down the right side of her face. She was wearing mourning, like I was, a band of black lace on her cap. A gold locket hung from a chain round her neck and I reached beneath my cloak, clutching my own. Mama, we’re home. We’re home.

Just in time, I remembered to slip the ring from my finger.

My knock was tentative and I watched them swing round in fear. A lump in my throat was choking me, I felt unable to speak, yet I had to shout as they began closing the shutters. ‘Please, please let me in . . . I’m sorry I didn’t let you know I was coming. I’m Pandora. Your niece . . . I’m Pandora Woodville. I’ve come back.’

The beautiful young woman unlocked the door and I knew to curtsy with my back straight and my chin in the air. Desperate to sound eloquent, I tried not to gabble my words. ‘I’m sorry I couldn’t let you know I was coming . . . forgive me for intruding like this.’

Across the room, Aunt Hetty gripped the back of her chair, her face ashen, her mouth tight. ‘Take off your cloak, my dear. And those wet shoes. You may not have told me you were coming, but that has not stopped me from expecting you. As soon as I heard about . . .’ Her voice caught and she reached for a candle. ‘Get warm . . . have something to eat. I’m going to retire to my room. I will see you at nine tomorrow morning. Miss Elliot will see to your comfort and show you where you can sleep.’

I held her stare, a thousand knives piercing my heart. No warm embrace. No sign of love. No holding me, no asking me about my mother and how she died. No questions about my journey. Just her stiff upper lip and haughty tone, her chin in the air, her penetrating eyes. I could hardly stop myself from crying. ‘Thank you. I’m so sorry . . .’

At the door, her silk skirt rustled as she swung round. ‘Sorry?’ Her voice dropped to a whisper. ‘Sorry that my prayers have been answered? That I have finally got you home?’

The door shut and Miss Elliot reached for my cloak. ‘My goodness, you’re very wet . . . Rain pooled on the flagstones around me, my footprints leading from the door. ‘Your hem’s completely soaked. Maybe you should change into something dry before we eat?’ Her voice was as sweet as her smile was gentle. ‘Come, sit by the fire while I go and light the one in your room. Get warm, Miss Woodville. You must have had a very long journey.’

Annie Rowe was staring at me. Holding up her eyeglass, she shook her head. ‘You haven’t your mama’s looks, have you, my dear? You always were an ungainly child.’

I forced back my tears. ‘No . . . Mama was very beautiful.’

‘Come to the candlelight.’ Her face was a mass of wrinkles, her skin almost translucent. I remembered her with dark brown hair yet now it was grey and thinning, parted in the middle, and coiled on both sides. She stretched out her arm, a heavy shawl wrapped around her shoulders. Her black brocade gown seemed rather too big for her, her velvet cap edged with black lace. ‘Your hair’s a terrible mess but that can be addressed.’ Her bony finger slipped beneath my chin as she turned my head. ‘Dear me. You’re the spitting image of your grandmother.’

A bolt of hope shot through me. ‘My grandmother was a lady.’

‘She was. Indeed she was. A real lady.’ A faraway look filled her watery eyes. ‘I was Mrs Mitchell’s personal maid before I became her housekeeper. We were of an age. Your mother was a wonderful lady. We all adored her.’

Now my cloak was off, I could feel the chill in the room. Despite the fire, the stone walls seemed to retain the damp. More memories came flooding back: the table groaning under the weight of garden produce, a huge basket of lavender waiting to be made into bags. Mama’s laughter rang across the kitchen, Annie Rowe smiling down at me, scolding me for climbing trees when I should have been sewing. And always my adored aunt, popping her head round the door, telling me she had found a new butterfly or a fat beetle and I must come quickly. The memories were so real, tears welled in my eyes.

Annie Rowe slipped her arm round my shoulder, a smile lighting her pale face. ‘Don’t cry, Abigail. You mustn’t mind Harriet. She’s a very private person . . . she’ll be ready to see you in the morning. She’ll forgive you in time, but she’s right. Your mother doesn’t approve of you marrying that man. You mustn’t go against your mother’s wishes.’

I stared back through my tears. She seemed lost in her own world. ‘But I’m Pandora, Miss Rowe – I’m Abigail’s daughter.’

Miss Elliot was watching us from the door. She seemed to glide across the room. Taking Annie’s hand, she led her back to her seat by the fire. ‘Miss Woodville must be tired after her journey. I’ll take her to her room now. The fire’s lit, and the bed sheets are airing. Miss Woodville is Abigail’s daughter, Annie. You remember now? It’s been a bit of a shock for you, hasn’t it?’

She lifted my bag, smiling as she walked to the door, and I reached for it, not wanting her to carry it. Who was she? Clearly not a servant as she was dressed so beautifully, but she was too young to be a teacher. She must be all of seventeen. I had no idea how to behave – should I let her take my bag or carry it myself? She was obviously prepared to light a fire and collect my bed linen, but she was not a maid.

She seemed to sense my thoughts. ‘I’m lately a pupil here, Miss Woodville. My only wish is to be a teacher. At the moment we’ve no maids . . . we’re just the three of us, and Susan, that is, who lives in the gatehouse. Annie is . . . Well, I think you saw how she slips into the past more often than not. But your room is ready – I’ll bring you some hot water.’

She held up the candelabra and I followed her down a stone corridor with an arched doorway on one side. Candlelight flickered against the bare walls, an oak door opening to a vast hall with a vaulted ceiling. A set of worn steps wound from the right and I gripped the banister with its carved figurines. It was as if Mama walked beside me. You used to peek through the banister like one of the angels.

The stairs led to a long corridor lined with heavy oak doors, the smell of beeswax mixing with lavender. Miss Elliot walked swiftly, her candlelight flickering on the ornate panelling. Glimpses of unlit brass lanterns flickered in the light, slates with names written in white chalk. Pausing by a second flight of steps, she looked up at them. ‘These lead to Miss Mitchell’s private rooms. The three bottom steps creak so she knows if anyone’s coming up.’

A memory stirred, a sense of childish excitement. ‘I remember these steps. I think . . . I might be wrong . . . but did my grandfather have his study up there?’

She smiled, pointing me further down the dark corridor. ‘His study’s at the top of the tower – through the arch at the end. I came just after Reverend Mitchell died, but I knew your grandmother. Mrs Mitchell was a wonderful lady, we all adored her. She was kind and gentle, and I was so sad when she died.’ Grace Elliot looked just like an angel, just how Mama must have looked. ‘Miss Woodville, I can’t tell you how happy I am you’ve come. Miss Mitchell needs you. She’s only just heard about your dear mother’s death and I think you saw how hard she’s taken it.’

She opened a door to a room lit with candles, a fire burning in the grate. ‘The room will soon warm up.’ A bed with a canopy stood in the centre, a dressing table with a large mirror on one side, a desk laid with writing utensils on the other. Two pairs of thick brocade curtains were tightly drawn, a pile of bedlinen folded neatly on a chair. ‘Have you other luggage, Miss Woodville?’

I shook my head. ‘My trunk and other bags were stolen in Philadelphia. I’ve only got a nightdress and one change of clothing. Miss Elliot, whose room is this?’

‘It’s never used – it’s always kept in readiness. Miss Mitchell insists on it being aired every day.’ A flicker crossed her beautiful face, her eyes welling with tears. ‘It’s the room your mother used to share with Miss Mitchell when they were children. Miss Mitchell has always kept it ready for your mother’s return.’ Her voiced faltered and she looked away.

I could hardly speak. ‘Would you mind if I stay up here? I’m rather tired. Perhaps, I can come down and bring my supper up on a tray?’

‘I’ll bring you a tray. I’ll make your bed and I’ll bring some hot water.’

It was all I could do to hold back my tears. ‘I’ll make my bed, Miss Elliot. You’ve been very kind. I don’t expect you to run after me like this.’

She held her delicate handkerchief to her eyes. ‘Will you call me Grace?’

Sudden emptiness filled me. I could not help it. She knew my grandmother, she had loved my grandmother, and my grandmother would certainly have loved her. ‘How long have you been at St Feoca, Grace?’

She paused at the door. ‘Ten years. I was seven when I arrived. I was an orphan. My aunt scrimped and saved to send me here. When she died, Mrs Mitchell kept me as a charity girl. I owe everything to your family, Miss Woodville. That’s why I stayed when everyone else left.’

Her voice sent a chill through me. ‘Why has everyone left?’

She clutched the cross hanging round her neck. ‘Miss Mitchell will tell you. She doesn’t like us to speak of it.’

Taking off my gold locket, Mama’s portraits smiled back at me. I had painted them on shell and cut them to the exact shape. Hardly seeing for tears, I put it on the dressing table and shook out my stiff clothes. All were salt-drenched, and not just from the sea. Ten years ago, I had been eleven. Ten years ago, Father had promised us we could return to St Feoca.

Chapter Five

St Feoca Manor: School for Young LadiesMonday 23rd March 1801, 8:30 a.m.

I woke to the swishing of curtains and grey light filtering into the room. ‘’Tis another damp day. Looks to be settling in good and proper.’ I did not recognise the voice, nor the woman bustling round my room. Hooking back the heavy curtains she stood, hands on hips, staring at the hem of my dress. ‘Seawater? Should have been rinsed through last night. It always leaves a mark.’

The fire was lit, a tray of steaming oatmeal and a bread roll on the table beside me. She seemed amused. ‘I’ve been in and out, and you sleeping like a log! I’m Mrs Penrose – but you can call me Susan. I’m from the gatehouse. I have to say . . .’ She swallowed, as if unable to find the right words. ‘That, filthy wet hem and muddy footprints apart, it’s good to have you here.’

She plumped up my pillow and I sat back, smiling at her. ‘It’s very good to be here.’

She raised her eyebrows. ‘Miss Mitchell won’t like your hair. Nor does she like anyone being late. Your boots are still wet; you should have stuffed them with paper.’ She was dressed in a grey serge gown with a white apron and mobcap. In her late thirties, her hands were red, her fingernails cut short. She had an air of everything being a problem, but when she smiled, she turned pretty and good-natured. ‘Eat this porridge – you’ve half an hour to get ready.’