1,82 €

Mehr erfahren.

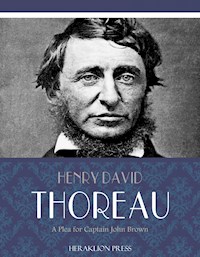

- Herausgeber: Charles River Editors

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) was an American philosopher and naturalist best known for writing Walden and Civil Disobedience. This version of Thoreaus A Plea for Captain John Brown includes a table of contents.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 46

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

A Plea for Captain John Brown

I TRUST that you will pardon me for being here. I do not wish to

force my thoughts upon you, but I feel forced myself. Little as I know

of Captain Brown, I would fain do my part to correct the tone and

the statements of the newspapers, and of my countrymen generally,

respecting his character and actions. It costs us nothing to be

just. We can at least express our sympathy with, and admiration of,

him and his companions, and that is what I now propose to do.

First, as to his history. I will endeavor to omit, as much as

possible, what you have already read. I need not describe his person

to you, for probably most of you have seen and will not soon forget

him. I am told that his grandfather, John Brown, was an officer in the

Revolution; that he himself was born in Connecticut about the

beginning of this century, but early went with his father to Ohio. I

heard him say that his father was a contractor who furnished beef to

the army there, in the War of 1812; that he accompanied him to the

camp, and assisted him in that employment, seeing a good deal of

military life- more, perhaps, than if he had been a soldier; for he

was often present at the councils of the officers. Especially, he

learned by experience how armies are supplied and maintained in the

field- a work which, he observed, requires at least as much experience

and skill as to lead them in battle. He said that few persons had

any conception of the cost, even the pecuniary cost, of firing a

single bullet in war. He saw enough, at any rate, to disgust him

with a military life; indeed, to excite in him a great abhorrence of

it; so much so, that though he was tempted by the offer of some

petty office in the army, when he was about eighteen, he not only

declined that, but he also refused to train when warned, and was fined

for it. He then resolved that he would never have anything to do

with any war, unless it were a war for liberty.

When the troubles in Kansas began, he sent several of his sons

thither to strengthen the party of the Free State men, fitting them

out with such weapons as he had; telling them that if the troubles

should increase, and there should be need of him, he would follow,

to assist them with his hand and counsel. This, as you all know, he

soon after did; and it was through his agency, far more than any

other’s, that Kansas was made free.

For a part of his life he was a surveyor, and at one time he was

engaged in wool-growing, and he went to Europe as an agent about

that business. There, as everywhere, he had his eyes about him, and

made many original observations. He said, for instance, that he saw

why the soil of England was so rich, and that of Germany (I think it

was) so poor, and he thought of writing to some of the crowned heads

about it. It was because in England the peasantry live on the soil

which they cultivate, but in Germany they are gathered into villages

at night. It is a pity that he did not make a book of his

observations.

I should say that he was an old-fashioned man in his respect for the

Constitution, and his faith in the permanence of this Union. Slavery

he deemed to be wholly opposed to these, and he was its determined

foe.

He was by descent and birth a New England farmer, a man of great

common sense, deliberate and practical as that class is, and tenfold

more so. He was like the best of those who stood at Concord Bridge

once, on Lexington Common, and on Bunker Hill, only he was firmer

and higher-principled than any that I have chanced to hear of as

there. It was no abolition lecturer that converted him. Ethan Allen

and Stark, with whom he may in some respects be compared, were rangers

in a lower and less important field. They could bravely face their

country’s foes, but he had the courage to face his country herself

when she was in the wrong. A Western writer says, to account for his

escape from so many perils, that he was concealed under a “rural

exterior”; as if, in that prairie land, a hero should, by good rights,

wear a citizen’s dress only.

He did not go to the college called Harvard, good old Alma Mater

as she is. He was not fed on the pap that is there furnished. As he

phrased it, “I know no more of grammar than one of your calves.” But

he went to the great university of the West, where he sedulously

pursued the study of Liberty, for which he had early betrayed a

fondness, and having taken many degrees, he finally commenced the

public practice of Humanity in Kansas, as you all know. Such were

his humanities, and not any study of grammar. He would have left a

Greek accent slanting the wrong way, and righted up a falling man.

He was one of that class of whom we hear a great deal, but, for

the most part, see nothing at all- the Puritans. It would be in vain

to kill him. He died lately in the time of Cromwell, but he reappeared

here. Why should he not? Some of the Puritan stock are said to have

come over and settled in New England. They were a class that did