Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

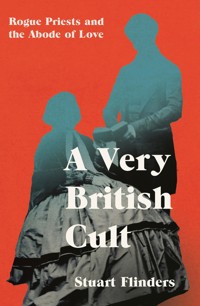

A secluded country house. A rogue Anglican Priest. Ceremonial sex and mislaid fortunes. This is the almost-forgotten story of Victorian Britain's strangest religious sect and its wealthy, mostly female, followers who believed they could ascend directly to heaven. Henry James Prince was a rogue Anglican Priest with a flare for the dramatic, and the founder of the Agapemone, or 'Abode of Love'. He also claimed to be the immortal conduit of The Holy Spirit and purportedly engaged in free love and ceremonial sex with his mostly female followers. But Prince's eventual death didn't mark the end of this strange set... he was promptly replaced by another. John Hugh Smyth-Pigott - otherwise known as the Clapton Messiah. The Abode transformed a sleepy, rural corner of Somerset into one of England's most notorious locations. While the followers shut themselves away and waited patiently for the end of the world, outrage grew - the word 'Agapemone' because a byword for licentiousness or idleness, used by Charles Dickens and Ford Maddox Ford. The reclusive Clapton Messiah became a fixture in the nation's papers, with frenzied efforts to discredit the organisation and undermine its leader. And still the cult grew. Expertly drawing on primary sources to tell the story of the Agapemonites in details for the first time, Stuart Flinders shines a light on the people drawn to the cult - the forced marriages; the swindled fortunes; the women condemned to asylums; and those who managed to escape from the Abode. It is also the story of two extraordinary men, whose claims of divinity were at the heart of this very British cult.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 396

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in the UK and USA in 2024 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

ISBN: 978-183773-147-3

ebook: 978-183773-148-0

Text copyright © 2024 Stuart Flinders

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typesetting by SJmagic DESIGN SERVICES, India

Printed and bound in the UK

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It would not have been possible to tell this story without the help of a great many people. I would particularly like to thank Kate Barlow and Ann Buckley, granddaughters of John Hugh Smyth-Pigott, the ‘Clapton Messiah’. They shared their family stories and photograph albums and allowed me to use their own research, interviews carried out in the 1980s with people who remembered their grandfather and the Agapemone, but who are no longer with us. I was also helped by members of the wider family: Wendy Carter and Penny Smyth-Pigott shared documents and diaries as well as photographs; Dermot Campbell and Fiona Hicks provided more photographs and useful information about the family. Professor John Morgan-Guy of the University of Wales Trinity Saint David kindly let me have a copy of a lecture he had given about the early life of Henry James Prince, Smyth-Pigott’s predecessor, as leader of the cult. I am also happy to acknowledge the assistance of archivists and librarians at the British Library, the Cadbury Research Library at the University of Birmingham, the South West Heritage Trust and the Hackney Archives. At Icon Books I am particularly grateful to Connor Stait and Steve Burdett.

CONTENTS

Introduction: ‘You whose eyes Shall behold God and never taste death’s woe’

1‘The glory of the institution’: The emergence of Brother Prince

2‘God will crush you’: The Nottidge sisters brought under Prince’s control

3‘I have seen God face to face’: The kidnapping of Louisa Nottidge

4‘Miserable dupes’: Agnes fights back

5‘A mark of God’s love for the flesh’: Prince takes a ‘spritual bride’

6‘A capital man of business’: Prince’s money-making exposed

7‘Come and hear!’: The Agapemonites on tour

8‘If men will not hear us, what are we to do?’: The Agapemone throws open its doors

9‘A dangerous amount of personal magnetism’: The emergence of the cult’s future leader

10‘That is Jesus!’: Smyth-Pigott declares himself to be the Messiah

11‘Down with the impostor!’: The Clapton Messiah faces an angry public

12‘Sexual intercourse is the highest form of spiritual worship’: Smyth-Pigott’s spiritual brides

13‘There is no such thing as sin’: Smyth-Pigott brought to book

14‘You know who I am? I am the Messiah’: Life at the Abode of Love

15‘My worthless enemies, whom I forgive’: The Clapton Messiah and the press

16‘Messiah Dead’: The death of John Hugh Smyth-Pigott

17‘The Day Thou Gavest Lord Is Ended’: The Agapemone closes

Afterword: ‘So many people … taken in so completely’

Bibliography

Endnotes

INTRODUCTION: ‘YOU WHOSE EYES SHALL BEHOLD GOD AND NEVER TASTE DEATH’S WOE.’ JOHN DONNE

The village of Spaxton is an ancient settlement, more than a thousand years old, but it remains largely unknown to outsiders. There is a church and a pub, but few tourists are drawn to that part of Somerset, preferring the heathland and woods of the Quantock Hills or the bustle of Bridgwater, a market town five miles away. Not much has changed there since the 1840s, when a small band of strangers appeared, building at first a chapel and then a large house that became their home. While they waited to move in they rented cottages nearby. Their more established neighbours in such a small community must have been curious about these recent arrivals, and in the autumn of 1846 the newcomers really gave them something to talk about.

Two of the new residents, sharing one of the rented cottages, were Julia Prince and Louisa Nottidge. They were at home together one November morning when a carriage drew up outside, and suddenly two men burst into their room. The intruders claimed that Louisa’s mother was ill and told her to go with them to see her, but she knew it was a lie and she refused to move. The men were not unknown to her. They were her brother, Edmund Nottidge, and her brother-in-law, Frederick Ripley. She was aware that her family disapproved of the new life she had chosen by moving to Spaxton and of her new friends, so the sudden appearance of Edmund and Frederick made her suspicious. No, she told them, she would not go into the garden with them to discuss it. If they had anything to say, they must say it there.

As the argument became heated Julia rose to her feet and asked the men to leave. ‘Gentlemen, your presence here is unpleasant to Miss Nottidge,’ she said. But the men would not budge. Alarmed at their behaviour, Louisa put her hand in Julia’s and they tried to leave the room together, but Edmund stopped them, forcing himself between the two women. He put his arm around Louisa’s waist, prised the women apart and dragged his sister out of the house. ‘Edmund, I will not go,’ said Louisa, pleading with her brother. ‘Julia,’ she cried, turning to her friend, ‘I am not going.’

Julia tried to hold on to Louisa, but Edmund grabbed his sister’s friend by the throat and pushed her away. Still struggling and screaming, Louisa caught hold of the iron gate outside the cottage. Ripley wrenched her hand off it and the two men dragged her in her slippers ‘without bonnet, shawl or anything of the kind’, as Julia said later, to the waiting carriage. There, a third man, Louisa’s cousin Edward Nottidge, was waiting. Helplessly, Julia watched as the men ‘drove furiously on’.

Louisa Nottidge had been kidnapped. Two days later, she was admitted to an asylum in London and remained there for well over a year.1 Louisa was single and wealthy, and she always claimed that her incarceration was simply her family’s attempt to take her inheritance from her. When she went to court to prove it years later, the judge ‘very much doubted whether, if in this case the plaintiff [Louisa] had been a man, or living under the protection of a husband, the defendants would have dared to have taken the step that they had.’2 ‘Is it not a foul outrage to law and humanity,’ asked The Times, ‘that such a person as Miss Nottidge should have been detained for 17 months within the walls of a madhouse?’3

However, there was more to it than that. Some members of her family were indeed concerned about her money when they planned the kidnapping, but not because they wanted to spend it on themselves. Louisa’s mother Emily had not seen her daughter for eleven months, since two strangers turned up at their home in Suffolk demanding she go with them. Louisa had told her mother: ‘I go; but it is like tearing the flesh from my bones.’ It was God’s will, she said. The men gave her two hours to pack, and Emily Nottidge found out where her daughter had gone only after six anxious weeks, fearing that she might be living ‘in the greatest sin and iniquity’.4

Louisa had joined a religious sect. It was led by Henry James Prince, a Church of England minister gone rogue, who claimed a direct line to the Holy Spirit. The world, he preached, was coming to an end. Sinners were about to get their comeuppance. The saved were about to be transported to heaven by God without the inconvenience and discomfort of death. But when? Prince led his followers to the luxurious mansion newly built in Spaxton, and there they waited. And waited. Their salvation assured, there was no longer any need for prayer. The sect, on the fringes of Christianity, became a cult as its members surrendered to the will of Prince, whom they called ‘Beloved’. The house took on a Greek name, the Agapemone, meaning ‘Abode of Love’, and, as the years went by, strange stories emerged of how that love was expressed, stories that suggested the Agapemone was little more than a harem for the enjoyment of Prince and the other leading men, outnumbered as they were by women. It was here that Prince had sex with a young woman as part of a ritual. Some said it took place in full view of his followers.

Still waiting to be called to heaven, many remained faithful for decades, but those who underwent a change of heart found it difficult to leave. There were dramatic escapes and even an armed stand-off in 1860 as one man tried to rescue his wife from the Agapemone. Some found a way out only by taking their own lives. Even in a more sceptical twentieth century, the sect survived, given new life when Prince’s successor declared himself to be the Messiah at a church in Clapton, London, in 1902.

This is a story of women forced into marriage with strangers, of families divided, of lives cut short. It is the story of a very British cult.

‘THE GLORY OF THE INSTITUTION’: THE EMERGENCE OF BROTHER PRINCE

1

Why was Louisa Nottidge so drawn to Henry James Prince and his strange commune, so determined to follow him that she rejected her own family? When they first met, four years before the kidnapping, he was the young curate at her parish church, still a minister of the Church of England. He arrived at St John the Baptist’s at Stoke by Clare in 1842.1 Stoke is a village deep in the Suffolk countryside, and Louisa lived not far from the church at one of the area’s grander houses, Rose Hill, with her father and mother, Josias and Emily, and four of her sisters. Josias Nottidge had earned a good living as a merchant and was now retired.2 He and Emily had had fourteen children, and a bracelet given as a gift by Josias to his wife contains miniature portraits of the eleven survivors. It sold for £20,000 in 2019.3 Although unmarried, Louisa and her sisters were by no means young. Louisa was the eldest at 39 when Prince arrived at their local church; Agnes the youngest at 24.4

Theirs was a devout family. Edmund Nottidge was ordained as a Church of England priest in 1830,5 but his sisters were looking for more from their faith than the gentle traditions offered by an English country church. ‘The minds of myself and sisters were highly susceptible of religious enthusiasm’, recalled Agnes later.6 ‘Enthusiasm’, ‘revival’, ‘reformation’ were encouraged by a new breed of preacher, urging a radical evangelical message on their parishioners. The words of the Bible had to be felt profoundly as well as understood. Prince was one such preacher. So great was the impression he made on the Nottidge sisters that not only did they attend services at his church, but they also visited him at home every day. Agnes explained:

Henry James Prince, by a great affectation of piety, and by declaring in his sermon and conversations to the effect that eternal misery would befal [sic] those who did not obey his exhortations, obtained much influence and ascendancy over me and my said sisters …7

Agnes’ reflections are about the only evidence of what made Prince so persuasive during his time at Stoke. But his record in his previous posting gives us some idea of how he went about his work.

Two years earlier, he had taken up a curacy at a church in one of the most beautiful settings in the country. High on a hill in Somerset, St Mary’s, Charlinch, would become, to Prince’s mind, a beacon for miles around.8 The rector there – effectively Prince’s boss – was Rev. Samuel Starky, who was born into the landed gentry. He was connected through his mother to the ancient Bayntun family, which had established itself in the reign of Henry II in the twelfth century. It embedded itself further into the aristocracy by grabbing confiscated monastic lands in Wiltshire under Henry VIII. Samuel’s older brother became Lord of the Manor of Bromham, but, as a younger son, Samuel himself entered the church.9 He wasn’t at Charlinch to greet Prince when he arrived, because he was ill and convalescing on the Isle of Wight, leaving Prince to run the parish as he saw fit.10 Prince did not want simply to lead parishioners in ancient and reassuring rituals. As far as he was concerned, they did not know God; his mission was to convert them. So pleased was he with the fruits of his labours that he would later sing his own praises in a book, The Charlinch Revival, published in 1842.

Evidence of a revival was slow to emerge. The parishioners did not take to him and the congregation shrank; by the end of his first year he had, by his own reckoning, saved no more than five souls.11 His first major convert was none other than the Rector of Charlinch himself. Starky claimed he was seriously ill and preparing for death when a copy of one of Prince’s sermons was delivered to his sick bed. It made such an impression on him that he recovered immediately and returned to Somerset.12

The Charlinch Revival began in earnest in November 1841, five months after Prince had been ordained priest.13 By this time, he seems to have given up hope of success, ‘the power of the Spirit appeared quite gone’. But one Sunday he suddenly underwent a transformation while standing in the pulpit. Initially, he was lost for words, but soon he began to speak, or as he later claimed, the Holy Spirit began to speak through him. His description of what happened next is written in the third person, as if he had observed it rather than taken part. The sermon was, he claimed, ‘searching as fire, heavy as a hammer, and sharper than a two-edged sword’. He continued:

As the spirit proceeded to dictate, and the minister to deliver the most awful appeals to the consciences of sinners, an extraordinary stillness of spirit stole over the people: even the children in the gallery, usually a turbulent and noisy set, seemed awe-struck, and sat looking in each other’s faces in silent astonishment. During the frequent pauses made in the discourse a death-like stillness pervaded the whole church, so very solemn that one almost seemed afraid to breathe lest something should be disturbed by it. Several men and women sobbed aloud; the heads of most dropped on their breast; the hearts of all were awe-struck.

In a footnote, he admits that not everyone was awe-struck: ‘One boy excepted.’14

Indeed, it was the children, the ‘hardened little sinners’, as he called them, that refused to succumb to his message, until one evening when he had them to himself at Sunday school. Prince’s account of what happened there, again written as if he were observing the Holy Spirit possessing his body, is disturbing:

… on this evening, the Holy Ghost came on the minister with the most tremendous power, so that the word of the Lord was really like fire. About twenty of the children were pierced to the heart by it [his sermon], and appeared to be in great distress; but the bigger boys still continued unmoved, and some of them even seemed disposed to laugh. In a short time, however, the word reached them, too, and they were smitten to the heart with the most dreadful conviction of their sin and danger: it appeared as if the arrows of the Almighty had pierced their very veins; indeed, the Lord really seemed to have made the mouth of the minister like a sharp sword; so tremendous was the power of the word then spoken. In about ten minutes the spectacle presented by the school-room was truly awful: out of 50 children present there were not so many as ten that could stand upright: boys and girls, great and small together, were either leaning against the wall quite overcome by their feelings of distress, or else bowed down with their faces hidden in their hands, and sobbing in the severest agony: it appeared positively as if the Spirit of God was breaking their hearts into pieces like a potter’s vessel. The most heart-felt anguish was written on almost every countenance that could be seen; whilst some of them looked as though they were inwardly wrung with the extent of the agony they endured. During the prayer that followed, the impression made by the Spirit became still deeper, till the walls of the schoolroom quite resounded with the sobs and cries of the children kneeling on the floor; and for some time after the minister had ceased to pray, they continued where they were, not weeping, but literally deeply wailing. When he left the room they followed him to the rectory, expressing their desire henceforth to forsake their sins and pleasures, and to seek the Lord. There were more than forty thus smitten with conviction; and most of them were so affected that for some time afterwards, they could scarcely speak for sobbing … Who can possibly resist the conviction that the ‘hand of the Lord hath done this …?’

It was as if Prince had cast a spell. A week later, he took stock. ‘The convictions of some of the children are becoming deeper’, he wrote. ‘In others they are wearing off.’ After three months the damage done by the emotional abuse he had inflicted on the younger members of his parish was clear:

About twenty children came to converse with us after the lecture to-day, in great concern: of these about fifteen are now stripped of hope in themselves, and are in a state of self-despair: twelve of them are boys from twelve to twenty years old … they are inwardly broken, stripped and emptied, so that not one single ray of hope from self dawns on them.

Prince was not alarmed; he was encouraged by this. Now, he thought, they would be ready to accept that their salvation lay not in their own hands, but through faith in God: ‘they see plainly that neither their tears, prayers, repentance, or amendment can avail them without faith’.15

The effect of Prince’s work was to divide the small community, as he himself observed:

Husbands threatened to murder their wives, and wives threatened to forsake their husbands, if they would not give up going to Charlinch. Nor did the converted children escape: some were coaxed, others frightened by their parents; whilst their unconverted brothers and sisters seemed to take a savage delight in turning them into ridicule, and in trying to provoke them that they might lose their temper.16

Reports of Prince’s behaviour reached his superiors, and when he divided his parishioners into the ‘saved’ and the ‘unsaved’, telling the latter to stay away from church, the Bishop of Bath and Wells intervened. On 4 May 1842, after Prince had ignored earlier warnings, his licence to preach within the diocese was withdrawn. But the Charlinch Revival was not quite over yet. Prince simply hired a room in the village and continued to preach independently at what he called the Charlinch Free Church, until he moved to his new job in Suffolk and met the Nottidge family.17

The misgivings of his bishop or his parishioners were never going to trouble Prince. That he would be special in the eyes of God had been written in the stars, he believed. He was born on 13 January 1811, ‘the year of the Great Comet and therefore of great significance’, he would tell his followers.18 His family lived in Bath at Widcombe Terrace, a fashionable street, once home to the novelist Henry Fielding.19 His father, Thomas Prince, owned two houses in the city and a warehouse in Liverpool. He had interests in two plantations in Jamaica,20 and in his will left a gift of land and ‘negroes’ to another son, a captain in the Middlesex militia.21 Thomas Prince died when Henry was five years old,22 and the child was brought up by his mother, Mary Ann. With another son already building a career in the Church, Henry’s mother steered him towards medicine, and after completing his training he began working at the Bath Hospital and Infirmary.23

His childhood and early adulthood were interrupted by bouts of illness, which he described as a disorder of the stomach.24 It became so serious that he underwent a ‘very painful’ operation when he was 24 years old, during which he nearly bled to death.25 Much of his convalescence was spent in the care of his mother’s lodger, Martha Freeman. Ten years older than Prince, she was the daughter of a West Indian planter, and they became very close, studying the scriptures together, especially the Song of Solomon, regarded as a celebration of sexual love.26 In this heady atmosphere something happened that was to shape Prince’s life hereafter. He was able to pin the event down not just to a specific day, 7 May 1834, but to the precise hour:

In the afternoon, at half-past four, having suffered under conviction of sin fifteen months, and during the last month with the utmost agony, it pleased God, of His infinite mercy, to reveal His Son Jesus Christ to me, by faith, whilst I was in earnest prayer in my bedroom.27

Prince had a new calling. He abandoned medicine and, with the encouragement of Martha Freeman, entered the Church. ‘The world appears to me a moral hospital, and all mankind are patients in it.’28 A few days after going into the tap room of a pub to tell ‘a savage set’ off for ‘much swearing and rioting’, he left Bath in February 1836 and began studying at St David’s theological college at Lampeter in Wales.29 Even here, among future clergy, Prince earned himself the reputation of a prig, flouncing out of a small party because alcohol was being served.30 ‘It vexes my soul to see the thoughtless levity in those around me,’ he said. ‘One might think they were educating for the stage rather than the pulpit’.31 But he was not alone. He surrounded himself with a core of like-minded young men, such as the former Royal Navy midshipman Arthur Augustus Rees, with whom he founded a regular prayer group.32 Prince, according to Rees, was ‘the glory of the Institution, both in scholarship and piety’.33

While at St David’s, Prince read the works of Gerhard Tersteegen, an eighteenth-century German mystic, who believed communion with God could be achieved only by the total absorption of an individual’s personality into the personality of God.34 It is clear from this time that Prince believed he too had become possessed by the Holy Spirit:

May 10. —I continued very dull in spirit all the evening, and was so in prayer until I began to pray for this poor girl [who was dying after a long illness], when, suddenly, almost as if the heavens were opened, – the Spirit descended upon me with such tremendous power. I could not have stopped from praying for her soul: … the consciousness that it was the Spirit, and not myself praying, and the encouragement thereby to continue in prayer; the conviction of God’s power and willingness to save her, and of the glory that would accrue to Christ in her salvation, – combined to call forth a fervour that amounted to ‘groanings that cannot be uttered’.35

Soon, he was seeking divine advice before making the most mundane decisions. If he went for a walk, would it rain? Should he take an umbrella?36 He even believed he had developed power over the elements:

April 12, 1839. —By the help of my God I have overcome an east wind. For three or four weeks a strong east wind has been blowing, and as this wind exerts quite a pestilential influence on my body, and has so often been the means of bringing me very low, when it began this time my flesh trembled. God, however, gave me faith to believe it should not injure me; nor did it, though I have been exposed to it daily. Yesterday, however, my faith failed, and, the wind being strong and the sun very hot, I expected to be laid up; when, lo, the wind shifted to the north! I have no doubt that God gave me special faith for the occasion, and when the faith was no longer needed, He took it from me. Neither do I doubt that I, through faith, subdued the east wind to the glory of God.37

When it came to exams, it was divine intervention rather than his own studies that allowed him to pass. He told himself it was God’s will that he should do the bare minimum for his classics exam, and he even forced himself to resist the temptation to revise for it. He felt vindicated when the exam was cancelled in honour of Queen Victoria’s coronation.38 Unfortunately for posterity, the Lord commanded him to stop keeping a diary: ‘October 28. —I have had no permission from God to write in my Journal since I have made the last entry.’39

Now that Prince had developed this direct line to God, he became less dependent on other sources of authority such as the Church and the Bible itself. These were traditional safeguards against an overreliance on personal perceptions of God’s will. It was as if Prince had reduced religion to gut feeling. Would he still feel himself bound by the laws of the land or even the Ten Commandments?

The college, through the vice-principal’s contacts, helped Prince to his first job at Charlinch,40 and he took with him Martha Freeman, his mother’s lodger. They had married in July 1838 after she, a Roman Catholic, had converted to Anglicanism,41 but if their relationship had developed through their shared love of the Song of Solomon, there was little evidence of passion in his diary. He celebrated it there not as an affair of the heart, but as a demonstration of God’s love.42

Prince kept in touch with the Lampeter Brethren through a series of letters, seeing himself as a latter-day St Paul as he exhorted them to remain aloof from the world and to follow God even at the risk of offending others.43 His relationship with the co-founder of the Brethren deepened when Arthur Rees married Prince’s sister, Eleanor, in February 1842, at the church in Bath where he himself had married Martha.44 But his own marriage came to an abrupt end when Martha died two months later.45

Within five months of the funeral, Prince had married again. It was, he said in a letter to George Robinson Thomas, a member of the Lampeter Brethren, God’s will:

I have married not to please myself or others – no, nor because I was permitted by the Lord to do so, but, and I say it calmly, deliberately, unequivocally – aware that the assertion will be ridiculed by most, doubted by many, wondered at by all, yet understood by angels and approved by God – I say that I have married, and married at the time simply, solely and entirely in obedience to God’s will, and by the direction of the Holy Ghost.46

Prince’s second wife survived much longer than his first, and she would stand by as he publicly took on at least one new lover. That was ‘God’s will’ too.

The new Mrs Prince was Julia Starky, sister of Samuel Starky, the Rector of Charlinch. She was five years younger than her husband, who was now 31. By the time of the wedding in July 1842, Prince had set about repeating his ‘success’ at Stoke, encouraged by the Nottidge sisters, after the Bishop of Bath and Wells had sent him on his way.47

In the new parish there were public duties, but Prince would also pray privately for four hours at a stretch; six would not be too much, he said. He knew someone who would pray for ten hours a day. There were all-night prayer meetings at Charlinch, and it is safe to assume that they would now have been introduced here.48 Then there were the books. Prince was prolific, publishing not only his account of his time at Charlinch, but also the letters written to the Lampeter Brethren. How You May Know Whether You Do or Do Not Believe in Jesus Christ, published in 1842, sold more than 19,000 copies.49

The tracts and hymns would stretch to nearly 6,000 pages in his lifetime.50 Reading them now gives no pleasure. The style is heavy and crudely imitative of the Bible, and meaning is often obscure, as one of his harsher contemporary critics noted:

Mr. Prince, in making use of Scripture language, appears to have several objects in view, but all grievously selfish. He will often throw passages together to confuse them, or will quote them for fear they may be used against himself, or use them to intimidate the undecided or weak …51

By now his claims and his methods, appealing as they might have been to Louisa Nottidge and her sisters, were beginning to divide his old friends, the Lampeter Brethren. His brother-in-law, Arthur Rees, now preaching in Sunderland, spoke out publicly about his claim to be the ‘Holy Ghost personified’, and Prince turned his back on him, denouncing him as ‘a traitor – one who had a devil and into whose flesh Satan had entered’.52

For a second time he came into conflict with the Church hierarchy, once again losing his licence to preach when the Bishop of Ely acted against him.53 A diary entry four years earlier had been prophetic: ‘My path, I feel assured, will be a very peculiar one … I foresee much severe trial, not so much from the world, whose persecutions and contempt affect me little, but from the church itself.’54

Smarting from his dismissal, Prince decided to free himself altogether from the constraints of the Established Church and go it alone. He had made tentative steps in this direction when he had continued to preach after his licence at Charlinch had been revoked, and already had a core of committed followers there. Starky technically remained Rector of Charlinch, but he had joined his mission along with two members of the Lampeter Brethren who were also confirmed Princeites: George Robinson Thomas, who had succeeded him as Curate of Charlinch, and Lewis Price, who had taken over from him when he left Stoke.55

With the Charlinch mission established, Prince opened a second front in Brighton. Premises near the Pavilion were hired and turned into the Adullam Chapel, the name being a reference to the cave where, according to the Bible, David sought refuge from King Saul. Prince and his followers, seeing themselves as persecuted and oppressed, became known as the Adullamites.56 The seaside town had become fashionable as a resort in the Regency period and was now more popular than ever. Most were drawn by the benefits of bathing in the sea, but in an age when many believed the end of the world really was nigh, a preacher offering a cure for the soul could draw great crowds too.

Having relinquished his position at Stoke, Prince could have faced money problems, but he had, throughout his career, a knack of surrounding himself with the wealthy and the generous, as well as the female. In the short term, he could rely on the money of his wife Julia and her brother Samuel Starky, but he was already softening up the Nottidge sisters in Suffolk. Starky had repeatedly told them that to be good Christians they had to disregard the advice of their parents and other members of the family and listen only to Prince. Now that Prince was in Brighton, he remained in constant contact with them through letters addressed to their servants, but which were intended to be read to the sisters. One, sent in September 1843, told them, in a deliberate echo of Biblical descriptions of the activities of Jesus, that Prince was now preaching to ‘large multitudes on the seashore’. He believed that God was gathering in his chosen ones and ‘our Lord would descend from Heaven, taking vengeance on those without’.

This was the signal for the women to follow the charismatic preacher. It was a decision that divided their family – their parents urged them not to go – but in October, remembering Starky’s words about listening only to Prince, they packed their bags and headed to Brighton.57

Louisa, Agnes and another sister, Harriet, rented a house in the town. Their mother had little choice but to go with them as chaperone. Two other sisters, Clara and Cornelia, joined them soon afterwards. So absorbed in Prince’s world did they become that when they received news that their father was gravely ill, the sisters were reluctant to travel to him until they were persuaded that it was the ‘will of God’. After Josias Nottidge died in May 1844, Emily and her daughters returned to Brighton.58

Meanwhile, Arthur Rees stepped up his campaign against his old friend and brother-in-law. Having failed to persuade him in their personal correspondence of his theological errors, Rees began circulating copies of Prince’s letters in which he claimed to be the Holy Spirit made flesh.59 Prince sent his wife Julia to Sunderland to try to stop him and urged the Nottidge sisters to spread a rumour among his congregation that the letters were forgeries.60

But, in spite of attempts to undermine him, the popularity of Prince’s brand of Christianity was spreading. At least seven small chapels were now functioning in Charlinch and in neighbouring communities.61 Samuel Starky, again officially on sick leave from his post as Rector of Charlinch,62 was enjoying considerable success preaching at Weymouth on the south coast, 60 miles from Charlinch. He was successful in love, too, marrying Ellen Perry there in 1845.63 But, increasingly, the attention of the Princeites turned to a tiny hamlet called Four Forks, part of the village of Spaxton, half a mile from Charlinch. Here, William Cobbe, an Irish64 railway engineer who had worked for the great Isambard Kingdom Brunel, started to build what would become a permanent home for the Princeites on land he had donated. It would later be known as the Agapemone, or Abode of Love.65 Cobbe was one of many Princeites whose devotion led them to fall out with their families. His family, like that of Louisa Nottidge, would later consider putting him in an asylum to prevent Prince getting hold of his money.66

The first part of the Agapemone to be built was the chapel, and, with work under way, fundraising for the project began in earnest. Samuel Starky contributed £1,000, his sister Julia, Prince’s wife, threw in her annuity of £80.67 The Nottidge sisters frequently made gifts of £20 or £30 to Prince to help with building costs. They collected money from his followers in Brighton and topped it up with another £300 of their own.68 But Prince realised there was more to be had from the wealthy Nottidge family.

On the death of Josias Nottidge, his daughters had each inherited £6,000 – equal to more than half-a-million pounds today.69 There was a limit to how much of this Prince could get his hands on immediately, because as long as they remained unmarried, ultimate control of the money rested with Frederick Ripley, the husband of another sister, Maria, with power of attorney. But if they were to marry, the full amount would go to the new husbands, the law at the time considering women largely incapable of handling their own affairs.70

‘Brother’ Prince, as he was now known, had already demonstrated a flair for obtaining cash from his followers. Louisa Nottidge had once received a note from him that read: ‘The Lord hath need of £50 to be used for a special purpose unto His glory. The Spirit would have this made known to you. Amen.’71

A handwritten note may have been enough to extract such relatively small amounts from his followers, but how would he get his hands on the thousands inherited by Louisa and her sisters? For that he would have to come up with a far more audacious plan.

‘GOD WILL CRUSH YOU’: THE NOTTIDGE SISTERS BROUGHT UNDER PRINCE’S CONTROL

2

The new chapel’s foundation stone was laid on 1 January 1845 with a small copy of the New Testament inside.1 Deputising for Prince for the occasion was George Robinson Thomas, one of his closest disciples. Thomas had been a member of the Lampeter Brethren, the group of earnest evangelicals of which Prince had been a founding member when he was studying theology. While some of the Brethren had fallen out with Prince as his claims to divine authority developed, Thomas remained loyal. Five months later the chapel was completed, and this time Prince would perform the opening ceremony himself. He invited the Nottidge sisters to join him to help celebrate the event, and Agnes, Clara, Harriet, Louisa and Cornelia left Brighton on Monday, 9 June, telling their mother they would be back by the weekend.2 Emily was no follower of Prince – she had once locked herself in a bedroom to avoid him when he visited her Brighton lodgings3 – and her fear that no good could come out of her daughters’ association with him was to be borne out by what happened over the next few days.

On their way to Spaxton, the sisters met up with Prince, as arranged, at Taunton. He was staying at the Castle Inn, they at Giles’ Hotel, but Prince had arranged for the Nottidges to pay for his stay as well as their own. On the Tuesday morning the women were sitting together at their hotel when Harriet received a message from Prince requiring her presence. She went across to the Castle and found Prince in a sitting room with Samuel Starky and his wife Ellen. Prince informed her that ‘she would give great glory to God by marrying Lewis Price’, one of his disciples. There is no evidence that Harriet had any feelings for Price and, given her age – she was 40 – she might have been expected to behave with greater caution, but such was Prince’s power over her that she immediately consented. Prince told her to return to the Giles’ but to say nothing of what had taken place between them, presumably to deny her sisters time to prepare for the ambush awaiting them.

Moments after she had rejoined them, a second message appeared, summoning Agnes into Prince’s presence. This time, Starky did the talking with Prince occasionally backing him up. Even though, at 28, she was much younger than Harriet, Agnes was expected to be a tougher nut to crack and a different approach was adopted. ‘God was about to confer an especial blessing’, they told her, but before they could reveal what it was, she had to make a solemn promise to do whatever was asked of her. At first she was reluctant to give her word, but was finally persuaded to commit herself without knowing what ‘God’s especial blessing’ would be. ‘It was in the mind of God,’ she later recalled, ‘that I should be married to Brother Thomas in a few days.’ This was George Robinson Thomas, Prince’s successor at Charlinch.

Agnes did indeed prove ‘difficult’ when it came to money, the very thing that made her so attractive to them. The marriage could not take place quickly, she told them, because she wanted to make a property settlement, the one legal way of avoiding having to hand over her personal wealth to her spouse on the wedding day. It was necessary, she told them, to provide for any family she might have. ‘There will be no need of anything of that kind,’ came the reply. ‘You will have no family – it would not be in accordance with your present calling. Your marriage will be purely spiritual, to carry out the purposes of God.’ Agnes returned to her hotel to find Thomas himself with her sisters, but, having been instructed not to speak about the arrangement, neither broached the subject.

At dinner that day, Prince informed Price and Thomas that Harriet and Agnes had agreed to marry them. The weddings, he told the two couples, were to take place at Brighton, but suddenly he changed his mind. Prince must have realised that it would present Emily Nottidge with an opportunity to interfere in his plans for her daughters, so he announced Swansea as the venue instead. Furthermore, they should head to Wales straight away rather than return to Brighton. The women pleaded with him to allow them to see their mother. They had promised to return by the end of the week and it would cause her ‘great sorrow’ not to see them before the weddings took place. Prince rebuffed them with a warning from the Bible of the dire consequences of straying from ‘the path marked out for us by God’. In the end he agreed to allow them to return to their home in Suffolk to collect some clothes on condition that they went straight to Swansea from there.

Two days later, presumably after attending the formal opening of the new chapel at Spaxton on 11 June,4 Harriet and Agnes, the two brides-to-be, set out for the family home, Rose Hill. On the same day, their sister Clara, a week before her 36th birthday, discovered that it was God’s will that she should marry the man behind the construction of the new chapel, William Cobbe. Clara was kept away from Brighton too and not even allowed to go to Rose Hill; she was told to go directly to Swansea, where she was reunited with her sisters at the home of another Princeite, Thomas Williams. The daughters were forbidden to write to Emily, their mother, either about their planned marriages or to tell her they would not be returning on the Saturday, as promised. Emily waited for them in vain and without explanation as Saturday came and went. But Prince must have thought better about leaving Emily completely in the dark and sent the news through one of his trusted acolytes.

Brother Thomas appeared on her doorstep, announcing that he was going to marry Agnes and that she would not see her daughter again until after the wedding. Hard on his heels came Louisa and Cornelia, showing no signs of relief that they had escaped a forced marriage. To keep tabs on them, Henry and Julia Prince and Starky came along with them. Having delivered them to their mother’s lodgings, the Princes returned to theirs. There was no room for Thomas to stay with them, but Prince informed Louisa and Cornelia that it was the will of God that he should stay at their lodgings. As Prince headed to his Brighton home, a row broke out in the Nottidge household when Louisa told her mother that there was to be not just one wedding in the family, but three. Not only was Agnes to be married, but Harriet and Clara too. Louisa calmly ordered servants to prepare a room for Thomas, but her mother ‘strongly remonstrated’ with her. Louisa had, she told her, been wrong to travel on a Sunday, breaking one moral and social code, and wrong to invite a strange man to stay in a house full of women, contravening another. Louisa, who was now 42 years old, stood up to her. Thomas went to the bedroom prepared for him; Emily, in despair, left the house to spend the night with friends.

What was Emily to do to save her daughters, their weddings now just days away? She turned for help to her son-in-law, Frederick Ripley, and the pair hastened to Swansea to make a last-ditch attempt to prevent the marriages. There were repeated efforts to persuade the women to change their minds, but they were adamant, and Emily and Ripley returned to London without them.5 However, Agnes had not given up on the idea of legal protection for her money. Before her father’s death, her parents had urged her, because of the size of her inheritance, to obtain a formal settlement when she came to be married, and she had agreed. Days before their planned wedding, she wrote to her fiancé Thomas about it. Inevitably, his reply invoked the ‘will of God’ argument:

My beloved Agnes, I must write to you just what the Spirit leads me to do. This I do with the more confidence because I believe you have an ear to hear what the Lord may say unto you, through him that loveth you. You mentioned your desire to have a settlement of your property upon yourself; this I assure you would be very agreeable to my own feelings, and is so still; but last evening, waiting on God, this matter quite unexpectedly was brought before me. I had entirely put it away from my thoughts, leaving it to take its course as you might be led to act; but God will not have it so; He shows me that the principle is entirely contrary to God’s word, and altogether at variance with that confidence which is to exist between us, who are ‘one spirit’.6

As for the promise made to her parents, ‘any promise made when you were unconverted, and which was not in accordance with the word of God, you are not bound, neither would it be right in you, to adhere to’.7 Agnes made no further protest.

On 9 July 1845 a joint wedding took place at St Mary’s Church, Swansea. It must have been a strange affair: no intimate relatives apart from the brides themselves; no close friends. In the absence of family members, the brides were given away by Starky in the presence of Brother Prince.8 News of the event even made it into the colonial press, with the Bengal Catholic Herald reproducing a report from a Welsh newspaper noting that the brides all wore white hats and black veils.9

Of the three marriages, Clara’s to William Cobbe would attract the least public scrutiny in the future, but her sisters faced years of difficulties: Price would hold onto Harriet only after abducting her and seeking the help of the courts; Thomas was to dismiss Agnes within a matter of months, leaving her destitute and expecting his child.

The chief beneficiary of the weddings in Swansea was, of course, Beloved, Henry James Prince. Each of the new husbands took control of his wife’s £6,000 inheritance and put the money at Prince’s disposal. He now had funding for an elaborate building project at Spaxton, expanding on the newly opened chapel. In the next few years a luxurious mansion with extensive gardens would appear there for the comfort of Prince and his followers.