3,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

For over four decades, Cameron McNeish has chronicled Scotland's majestic landscapes and the outdoor communities who inhabit them. While much has changed, especially in terms of conservation and access, the hills themselves remain little altered, as do the reasons people visit them. In this collection of essays and diary entries, Cameron shines the light of experience on memory, and renews his vision, keen to share his insights with the many people who love Scotland's outdoors.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Also by Cameron McNeish

Highland Ways (KSA)

The Spurbook of Youth Hostelling (Spurbooks)

The Spur Master Guide to Snow Camping (Spurbooks)

Backpacker’s Scotland (Robert Hale)

The Backpacker’s Manual (Nordbok)

Ski the Nordic Way (Cicerone Press)

Classic Walks in Scotland, with Roger Smith (Oxford Illustrated Press)

The Munro Almanac (NWP)

The Corbett Almanac (NWP)

The Best Hillwalking in Scotland (The In Pinn)

The Wilderness World of Cameron McNeish (The In Pinn)

The Munros, Scotland’s Highest Mountains (Lomond Books)

Scotland’s 100 Best Walks (Lomond Books)

The Edge – One Hundred Years of Scottish Mountaineering, with Richard Else (BBC)

Wilderness Walks, with Richard Else (BBC)

More Wilderness Walks, with Richard Else (BBC)

The Sutherland Trail, with Richard Else (Mountain Media)

The Skye Trail, with Richard Else (Mountain Media)

Scotland End to End, with Richard Else (Mountain Media)

There’s Always the Hills (Sandstone Press)

Come By the Hills (Sandstone Press)

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by

Sandstone Press LtdPO Box 41Muir of OrdIV6 7YXScotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Cameron McNeish 2022

Editor: Robert Davidson

The moral right of Cameron McNeish to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-913207-86-1

ISBNe: 978-1-913207-87-8

Jacket design by Raspberry Creative Type, Edinburgh

Ebook compilation by Iolaire, Newtonmore

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Foreword

1. Introduction

2. The Big Days

3. Hands Required

4. Birds and Beasts

5. Against the Elements

6. Slow Adventure

7. Before the Hikers

8. Water, Water, Everywhere

9. Mountain Folk

10. Around the Edges

11. More Than a Day

12. Protect and Preserve

13. Furth of Scotland

14. Changing Times

Acknowledgements

I mostly walked alone when compiling my various weekly newspaper offerings, but the articles would never have reached publication without the encouragement of others. Even confirmed loners have to rely on team efforts from time to time, so a huge thanks to the staff and the editors of the papers I worked for over the years, especially the late Ken Jones, Ken Smith and Gavin Musgrove of the Strathspey and Badenoch Herald and Andrew Jaspan, Richard Walker, Calum Baird and Darren Bruce at the Sunday Herald and Newsquest Ltd. Special thanks to Gavin and Darren for giving me permission to reproduce those essays that first appeared in their publications.

A sincere thanks to my good friend, editor and publisher, Robert Davidson. Without his constant encouragement and his own specialist hill-going knowledge, not to mention his excellent editing skills, this book would have been all the poorer. The whole team at Sandstone have been a joy and a delight to work with.

Thanks also to Anne MacLeod for permission to reproduce her poem, ‘Coming Back to Meall Fuar Mhonaidh’.

An inspiring presence in my working career as an outdoors writer over the past forty years or so is my good friend and erstwhile colleague Chris Townsend, and I’m thrilled he has written the foreword to this book. Chris and I began working together on my own magazine, Footloose, in the early eighties and, when I became editor of The Great Outdoors magazine in 1990, Chris was the writer I desperately wanted on board with me. Britain’s most prolific long-distance backpacker, three-times Munroist and the first man to climb all the Munros and Tops in one continuous expedition, Chris is not only the UK’s most experienced hiker but probably our wisest. I’m delighted his name will grace this book alongside my own.

As always, thanks to my wife Gina for putting up with all the foibles of an outdoor writer for half a century. She’s always been there for me when hill days haven’t gone the way I expected, and she’s always been there to lift me up when I was down. Fifty years of married life – wow, who’d have believed it?

Finally, this book is dedicated to the other two ‘G’s in my life, my two sons, Gordon and Gregor.

List of Illustrations

SECTION ONE

A snow covered ridge on Beinn Liath MhorBen Tee above an autumnal Loch OichBinnein Beag in the MamoresCoastal scenery at Hallaig, Isle of RaasayEvening light on the mountains of LettereweEvening light on Strathfarrar ridgeFollowing the wall over Black Shoulder on Cairnsmore of CarsphairnFuor ThollHallaig, the scene of Sorley MacLean’s great poem on RaasayLoch Hourn, Barrisdale BayLeaving Glen Bruar on the ancient Minigaig routeLiathach from Loch ClaireLooking towards An Teallach from A’MhaighdeanOn Ladhar Bheinn above Loch HournRejuvenated Glen Feshie. Trees grow from a luxuriant carpet of mixed vegetationThe author outside Davy’s bourach on Jock’s RoadThe Carn Mor Dearg Arete on the Tranter RoundThe dispossessed scratched their messages on the windows of Croick ChurchThe path rises into Coire Lair with Fuor Tholl dominatingThe ptarmigan, a bird of the high places that could be a casualty of climate changeThe Skye CuillinThe summit of Beinn Macdui, the UK’s second highestThe summit view from A’MhaighdeanSECTION TWO

Approaching Loch Errochty Arkle, on the Sutherland TrailBen TianavaigBy the Falls of GlomachCairn Toul and Sgurr an Lochain Uaine from BraeriachClimbing Can a’Chlamain from Glen TiltCould Scotland’s only reindeer herd be at risk because of climate change?Eaval, North UistEn route to Loch DubhGylen Castle, KerreraLooking back towards the CheviotLooking south from the slopes of Ben NevisLooking towards Beill Macdhui from BraeriachLuxuriant Scots Pines in Glen FeshieOn the South West Coast Path in CornwallThe bothy at Burnmouth, Rackwick BayThe highly controversial mountain railway on CairngormThe Old Man of Hoy; some of the most amazing scenery on OrkneyThe scrambling section below Carnedd LlewellynThe Stack of HandaThe Table, in the heart of the QuiraingTryfan, from the slopes above HelygUpper Glen Feshie, rewilded and flourishing

Foreword

by Chris Townsend

Many decades ago, a keen young backpacker and hillwalker was nervously planning his first trip to the Scottish Highlands. Everything he’d heard about this then almost mythical land said it was much vaster and more serious than the English and Welsh hills he knew. This was back when the Internet only existed in science-fiction, so he wrote a letter to someone whose writing about Scotland he’d seen in the journal of the Backpacker’s Club. I was the young walker and the person to whom I wrote the letter was Cameron McNeish. I’m pleased to say he wrote a helpful and encouraging reply and I went to the Scottish Highlands, had a great time, and fell in love with the mountains and the wildness.

Not so many years later I met Cameron at an outdoor event, probably a trade show which we both used to attend regularly to look at new gear and meet others in the outdoor business. By then he was writing regularly for walking and climbing magazines, something I was just starting out doing. We got on well and have been friends ever since. As well as helping inspire my writing Cameron also taught me cross-country skiing in those long-gone days when snow from the glens to the summits was taken for granted. I remember he was a patient teacher – I was not a natural skier and some of the others in the group weren’t much better. We learnt enough for him to take us up Creag an Leth-choin in the Cairngorms and I was enthralled. A mountain on skis! What could be better? I’m still not sure I’ll ever forgive him for leaving us at the top of the Cairngorm ski resort and saying ‘make your own way down’ though. That descent is still one of the most terrifying I’ve ever done!

Later I wrote for Cameron for many years when he was editing outdoor magazines. He took this work seriously and raised the standard of outdoor journalism as well as using his platform as editor to campaign on conservation and access issues. Sadly, as this book shows, many of the matters he raised, and continued to raise over the years, are still urgent concerns.

Over the years we’ve been on several trips together, from day walks to overnight camps – I remember a December plod through the Gaick Pass in sombre, sleety conditions where only Cameron’s companionship gave enjoyment – to two weeks on the challenging GR20 long-distance path down the rocky spine of Corsica, where Cameron’s confidence and joy on steep rock gave me the nerve to deal with places a little beyond my comfort zone. Well outside Cameron’s comfort zone, though for vastly different reasons, was a mountain marathon we did together in the Peak District. After two days running round peat bogs and groughs on Kinder Scout and Bleaklow, Cameron swore he’d rather have spent the weekend walking round the streets of Manchester, and he was never coming back. And he didn’t for twenty years, until a rather more pleasurable visit described in this book.

On these walks and adventures we discussed a wealth of thoughts and ideas about the outdoors and nature. We shared our love of writers who’d influenced us both such as John Muir and Colin Fletcher, both of whom I’m pleased to see appear in these essays. We talked of conservation and politics – the last can’t be ignored if you’re concerned about the first – and wondered about the world we were bequeathing to the future. But the main thing I remember is the companionship of someone who shared my passion and joy in the hills and wild places.

As well as editing magazines Cameron also contributed regular columns to the Sunday Herald and the Strathspey and Badenoch Herald for many years and it’s those that he’s collected together for this book. I read most of them at the time, especially those in the Strathy, as this became my local newspaper when I moved up to Strathspey a decade before the twentieth century ended. Reading them again I’m impressed with the breadth of knowledge and diversity of interest reflected in them. As well as hillwalking and mountaineering there are essays covering natural history, the weather, mythology, history, outdoor people, islands, conservation and more. There is so much packed in here. Anyone wanting to learn about Scotland, and the vast majority of the essays are about Scotland though there are a few dips south of the border, will learn a great deal here, all imparted in Cameron’s easy going fluent style that conjures up everything he describes so well.

Cameron is usually regarded as an ‘outdoor’ writer, that is someone who writes about hillwalking, mountaineering, and adventures in wild places. A current trend is for ‘nature’ writing, which is about wildlife, and interactions with nature, apparently separate from the ‘outdoors.’ I’ve never liked this division, this pigeonholing. So many writers cover both. Cameron certainly does. There are deep thoughts here about conservation and wildlife as well as exciting adventures in the hills. This book is both nature writing and outdoor writing. And all expressed with passion, energy, and enjoyment.

Having all these essays together in one place gives them a power and significance greater than they had as individual stand-alone pieces. Themes can be followed, Cameron’s developing thought processes revealed. Divided into sections, each with a new introduction from Cameron, it’s fascinating to read decades of words on wildlife or mountain people or islands all together. This is an important collection of work.

Introduction

Professional outdoor writing is an unusual occupation, an existence dominated by obsession and yearning, ambition and reality, occasional feasts and many famines. On one hand you earn a living from doing those things you love best, but on the other your livelihood depends on being outside at all times of the year and in all weathers. If illness or injury strike, your means of earning a living are considerably reduced. In addition, whilst days on the hill or mountain are creatively inspiring, the downside is having to spend almost as much time in front of a computer screen at home, putting words to the experience so others may enjoy it vicariously. The sheer delight of simply going out for a hillwalk for its own sake fades to almost nothing.

My lifelong passion has been climbing hills and mountains, both at home and abroad. At various times I’ve obsessed on rock climbing, winter climbing, ski touring, backpacking and that most manic and inexplicable game, Munro-bagging. I moved my family to the Scottish Highlands to be close to the hills and, after working for the Scottish Youth Hostels Association in Aviemore, became an outdoor instructor, writing articles and books first thing in the morning and last thing at night. I quickly understood that doing both jobs wasn’t sustainable in the long term, so I chose to write.

I chose wisely. It was a risky thing to do but I was fairly comfortable with risk. Fundamentally part of the climbing game, mountaineers learn how to manage it through experience and the gaining of skills, processes that apply as fully to the rest of life. Risk management in the writing game essentially boils down to two things: finding a regular source of freelance work to fit beside, if possible, full-time employment. When I began writing professionally, very few newspapers were interested in outdoor topics and full-time jobs as an outdoor writer were as rare as hen’s teeth. Purely by chance I met a man by the name of Stephen Young who owned the Northern Scot group of newspapers. One of his titles was the Strathspey and Badenoch Herald and I managed to convince him that, as more and more outdoor enthusiasts were moving to the Aviemore area, which was fast becoming one of the ‘adventure capitals’ of Scotland, the local paper should serve them with a weekly outdoors column. He agreed and I wrote my first column for the ‘Strathie’ in early 1979, a weekly essay I contributed for thirty-two years.

A few years later I become the Deputy Editor of Climber & Rambler Magazine for a company called Holmes McDougall Publishing Ltd who paid me a regular salary. I became editor the following year and, in 1990, became editor of The Great Outdoors magazine, a role I enjoyed for the next twenty years. In addition to my weekly Strathie column I became the outdoor columnist for a newspaper called Scotland on Sunday between 1996 and 1999.

The company that owned The Great Outdoors magazine also owned a couple of newspapers and were intent on launching a new Scottish Sunday title called the Sunday Herald to compete with Scotland on Sunday. A well-known and respected editor called Andrew Jaspan was brought in to launch and run the new paper. We happened to be standing side by side in the men’s loo, doing what comes naturally, when he asked me why I was writing for a competing newspaper. ‘Because they asked me,’ I answered simply. ‘If I asked you to write a weekly column for us would you do it?’ he retorted. I said I would and jumped ship to contribute a weekly ‘walks’ column to the Sunday Herald for the next fifteen years.

Writing a weekly local newspaper column is a huge privilege, but not always easy. It takes considerable commitment and it’s difficult not to repeat yourself, so the content of my Strathie column changed over time. From walk descriptions I became more campaigning in my output, commenting on a range of environmental subjects. To reflect this, Ken Smith, one of my editors, changed the title of the column from ‘Out of Doors’ to ‘McNeish at Large’, and I became the voice of dissent amongst local landowners, developers and politicians. I was extremely critical of ski developments on Cairn Gorm and my thoughts didn’t win me many friends among the ski community in Aviemore. On one occasion, while taking a group of schoolchildren into the Northern Corries I was confronted by Bob Clyde, the General Manager of the ski-lift company who told me to ‘get off ma mountain’. I had one even more vociferous critic during my time with the Strathie, the late Donnie Ross, a local shepherd whom I admired greatly. Sadly, my admiration was not reciprocated. In me he saw everything that threatened his traditional way of life. Critical of sheep-farming, I called them ‘hooved locusts’, just as John Muir had done in Yosemite. I advocated for more woodland instead of monoculture grouse moors, and thought there were too many red deer and they should be culled. Worst of all in Donnie’s eyes, I wasn’t a local highlander but came from Glasgow.

Life as a columnist on the Sunday Herald brought less criticism. Who could take offence at someone describing a walk in the wild places? My ‘Peak Practice’ column necessitated a lot of travelling as it was important to cover routes in all parts of Scotland and even a few in the north of England. Occasionally I would jump in my old campervan and spend a long weekend in some part of the country, walking two or three routes over the weekend and storing them for future use when the weather was particularly bad.

Compiling some of these old newspaper columns into a book has been a fascinating and revealing experience and has confirmed something to me that I long suspected. Progress in terms of environmental management and conservation in Scotland is an extremely slow process. I was writing about land reform, raptor persecution, ski development and deer fencing over thirty years ago, and there has been little positive development on any of these issues in the intervening years. In a Strathie column in 2002 I wrote critically of Highlands and Islands Enterprise’s ownership of the Cairn Gorm estate, suggesting that as a Government development agency they should withdraw and transfer ownership to either the local community or the incoming National Park board. As Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE) they are still on Cairn Gorm, controversially pumping millions in public funds into a succession of tenant ski companies that have all gone bust. Now they are bailing out a funicular train that has failed spectacularly, an uplift scheme that I described as a white elephant as far back as 2002.

In 1997 I wrote about the extravagant cost of deer fencing to the public purse and how much more effective deer culling and the removal of sheep would be in allowing young trees to grow. Today there are literally hundreds of miles of new fencing going up throughout Scotland as landowners cash in on the Scottish Government’s Forestry Grant Scheme to implement new woodland creation. On the one hand it’s encouraging to see the Scottish Government prioritising new woodland growth, but it subsequently demoralising to realise that much of this new growth will be for timber production with its associated issues of clear-fell and increased road freight. As I discovered to my cost only recently, many landowners are erecting miles of fencing but failing to put in regular access points, one of the fundamental requirements for landowners and managers in the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. The responsibilities contained in the Scottish Outdoor Access Code are supposed to work two ways: we walkers have responsibilities, but so do landowners and land managers. Many of them are failing in these responsibilities by excluding people from vast tracts of land. Claiming millions of pounds of taxpayers’ money to fence out not only the deer and sheep, but also those same taxpayers.

It’s not all bad news though. There is much more awareness of raptor persecution in Scotland today, although I’m not sure how many more sea eagles, golden eagles, buzzards, hen harriers, red kites and peregrines have to be poisoned or shot before our Governments decide to do something positive about it. Likewise, recent years have seen the reintroduction of beavers to some of our rivers, albeit a tightly controlled reintroduction with an insane licensing system that allows some farmers to shoot them if they feel they are adversely affecting their land. It’s taken decades of campaigning for beavers to be reintroduced in Scotland. I hate to think how long it might take before politicians approve of reintroducing the lynx. As for wolves – forget it!

Perhaps the biggest change I’ve seen in almost fifty years of writing about our hills is our nation’s general attitude to the outdoors and nature.

The dark cloud that was the Covid-19 pandemic and its associated lockdowns had an unexpected silver lining. It increased awareness of the basic need we have for nature and the natural world. During the crisis of 2020 and 2021 we heard much about ‘mental health’. The term covers a huge range of conditions but, on this occasion, I’m referring to those issues caused by the restrictions of lockdown: worry, stress, loneliness and isolation. To some folk these are merely an irritant, but for others they can become chronic mental health issues that require treatment.

I’ve been convinced for many years, and have written about it for just as long, that regular encounters with the natural world can reduce the stresses caused by living in a highly pressurised society in which many elements are beyond our immediate control, or as in the Covid crisis, a sense of entrapment, loss of freedom or even deep concerns about the long-term future.

Many who have lost their jobs and income, and particularly those who have lost loved ones to this deadly virus, may react negatively or even angrily to my suggestion of going for a walk in the woods. I am overwhelmingly aware that I may sound trite and condescending, but even in such awful circumstances an exposure to the natural world can alleviate stress, depression and even grief.

There have been many studies that have shown the positive relationship between exposure to the natural world and well-being. Whilst nice views and pleasant countryside appeal to our sense of beauty there are also chemical reactions taking place in our body that create a natural drug-like effect in our brain. A natural high, as potent and addictive in its own way as cannabis or crack cocaine! But, and it’s an enormous but, as more and more people discover this phenomenon, as more people tune into nature as never before, the natural world itself has been on the receiving end of what has been described as ‘lockdown surge’, and we have to be reminded of our responsibilities. Most important of all, we must recognise that we are not divorced from the natural world but part of it and, because we are part of it, have to treat it with love and respect. If we do that, we will be rewarded with those mental health benefits I mentioned, benefits and blessings that are lost if we have to wade along footpaths covered in litter and cold campfire remains, or become part of an uncaring public that gathers in popular tourist hot spots to the detriment of everything that made the place special in the first place.

It’s good to remember the wonderful quotation from the American forester, writer and ecologist Aldo Leopold: ‘We abuse the land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see the land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.’ I hope the essays that follow will reflect some of that love and respect, and in reading them some of that appreciation of our wild places may rub off on you. We have entered a crucial period in our custodianship of a planet that we haven’t loved and respected very successfully to date. I published my first article about global warming in 1978 and our battle against it hasn’t advanced much in the intervening years. Global climate change is the biggest test any of us has ever faced and it can’t be left to politicians to sort out. The fightback begins with us, you and me, and we can begin by gaining an understanding of the workings of a natural world that includes us, affects us, and depends on us, not for the survival of the planet itself, but for the survival of mankind on the planet. Earth could cope very well without us.

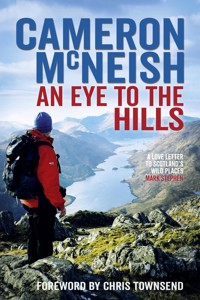

The following essays (with dates of original publication) also reflect some of the delights, joys and challenges the outdoor life can offer, written over a period of forty years or so. While nothing in life is as constant as change, the hills themselves thankfully remain largely inviolate and immutable, their spirit of ancient mightiness still offering life-affirming experiences. The title of this book, An Eye to the Hills reflects that longevity but it also reflects something else. Psalm 121 includes the popular lines: ‘I to the hills will lift mine eyes, from whence doth come my aid?’ Unfortunately, many people ignore the question mark. The psalmist is asking a question, not making a statement. His aid doesn’t come from the hills but he gives the answer to his question in the next line of the psalm: ‘My help cometh from the Lord, who heaven and earth has made.’ What I like about this psalm is the recognition that the hills may not provide the immediate aid, but can provide something else. The psalmist lifts his eyes to the hills for inspiration, for revelation, for illumination, something that I and many others have been doing for a long, long time. I hope they will bless you in the same way.

Here endeth the lesson.

CHAPTER ONE

The Big Days

There are big days on the hill and even bigger days. Some may be long in terms of distance, although shorter days in terms of mileage can still be big because of the amount of climbing involved. Then there are the days that are big because of an element known as the ‘long walk-in’.

Because of our extensive road network, even in the more remote parts of the Scottish Highlands and Islands, long walk-ins are now relatively rare. Indeed, one of the attractions of hillwalking in Scotland is that you can usually climb your hill, or group of hills, and be in the pub by opening time, but that’s not always the case. The Fisherfield Munros include a spot near A’ Mhaighdean that is thought to be the most remote in the land, so that and its neighbours require a long walk-in from Kinlochewe, Poolewe or Corrie Hallie near Dundonnell. These particular long routes are generally on good tracks where a mountain bike may be useful.

The Cairngorms, their northern remoteness diminished nowadays by easy access to the Cairn Gorm Mountain car park in Coire Cas, once necessitated a very long walk-in from Coylumbridge. Even today the big hills of the southern Cairngorms still require a hefty trek from the Linn of Dee or Allanaquoich to reach them. The Knoydart Munros, on their wild peninsula between Loch Nevis and Loch Hourn, the lochs of heaven and hell, require a long walk-in from either Kinloch Hourn in the east or Inverie in the south. Hardier types, or masochists, may prefer the wilder route from Glen Dessarry via the rain-soaked and boggy Mam na Cloich Airde to Sourlies at the head of Loch Nevis.

There are strong arguments in favour of the long walk-in, both from the points of view of physical readiness and deeper appreciation.

The Cairngorms require long and steady ascents through forests, climbing steadily below a canopy of Scots pines, through alpine zones into alpine-arctic zones with associated wildlife and vegetation, to the higher realms through skirts of ancient pines that become more storm-tossed and stunted the higher you climb, eventually beyond the tree line. Here you can comprehend the different types of landscapes in a holistic sense, experiencing their connectedness as you ease yourself upwards. Exiting the trees also begins another stage, climbing the lower slopes into glacier-scooped corries by way of narrow ridges onto the vast arctic spaciousness of plateaux that are as remote and isolated as they were a century ago. No such experience is possible when you step out of a heated vehicle onto a tarmac car park with dozens of other cars, coaches and buses, and shivering tourists.

The seven-mile walk from Kinloch Hourn to Barrisdale is a coastal adventure I’m particularly fond of, following the shoreline of Loch Hourn past the abandoned homes and former townships at Skiary and Runival, beyond the old and now roofless church at Barrisdale to the wonderful view of Ladhar Bheinn across the waters of Barrisdale Bay. Loch Hourn, often described as the grandest of the fissures that tear into Scotland’s west coast, reaches far and deep inland from the Sound of Sleat, winding into the heart of the country like a Norwegian fjord. The great highland writer Seton Gordon compared it to a ‘lake of the infernal regions’, and the comparison is not at all fanciful. Loch Hourn has acquired an aura of mystique through Gaelic mythology as the ancestral home of Domhnull Dubh, the Devil. One school of thought suggests that Hourn is a corruption of Iutharn, which means Hell. Another interpretation is that the name is possibly Norse, meaning Horn, which could perhaps be corroborated by the curving sweep of the loch. Whatever the meaning the walk along its rocky shores is always wonderfully evocative. It is to be entertained by oystercatchers, herons and gulls and there is always the chance of spotting an otter or a stravaiging sea eagle.

The long walk-in to climb a hill, or group of hills, occasionally requires the use of a tent or a night in a bothy, which can add to the experience, and I must confess to a hint of envy for those super-fit trail runners I see so much of on the hills these days, hill-athletes who are capable of jogging over huge swathes of hill country with comparative ease. The exploits of these folk leave me breathless with admiration.

Many years ago, inspired by an article I had read in the Scots Magazine, I attempted to walk from Ben Nevis over the Munros of the Aonachs, the Grey Corries and the Mamores and back to the summit of the Ben within twenty-four hours, and almost made it but ran out of time and energy just below Stob Ban. The route is known as the Tranter Round, and was first completed in 1964 by the late Philip Tranter who sadly died in a car crash while returning overland from a mountaineering trip to the Hindu Kush. His time for this forty-mile route, with over 20,000 feet of climbing, was later superseded by the fell-runner Charlie Ramsay who extended it by adding the five Munros that surround Loch Treig: Beinn na Lap, Chno Dearg, Stob Coire Sgriodan, Stob a’ Choire Mheadhoin and Stob Coire Easain. With profound serendipity this created a challenge of twenty-four Munros in twenty-four hours, an astonishing distance of fifty-six miles with 28,000 feet of ascent, almost the height of Everest.

The Glen Shiel area of Wester Ross is another rich in multi-Munro big days. A Tranter-like round starts at the Cluanie Inn and traverses the South Glen Shiel ridge followed by a tough re-ascent to take in the Five Sisters of Kintail and the ridge of Ciste Dubh. Many hillwalkers are happy to confine their big days to the completion of the South Glen Shiel Ridge, with seven Munros for the tick list, or a traverse of the Five Sisters of Kintail with three Munros. A boggy walk-in to the SYHA hostel at Alltbeithe from Melvich or Cluanie gives access to the big hills of Affric and the potential for even more.

Not all big days require a long walk-in though. Some, although relatively short in distance, require a lot of climbing, those roller-coaster routes that take in several summits in a day. I’ve described a couple in this chapter, the Ros-Bheinn group and the Tyndrum Corbetts are good examples, the latter being a hill round I often used to gauge my hill fitness when preparing for big backpacking trips abroad.

Another big day that will test your mountaineering skills to the limit is a traverse of the Cuillin Ridge on Skye. Only six or seven miles in length, its eleven Munros will task you with over 13,000 feet of climbing, not to mention the other sixteen non-Munro tops en route. Much is on exposed, rocky ridges and you’ll have to negotiate some sustained rock scrambles along the way including the highlight of the route. The Inaccessible Pinnacle is the most technical Munro on the list, requiring rock-climbing and abseiling skills for which you will have to carry a rope, slings and the paraphernalia of the climber.

In the following essays I’ve described a range of longer days I’ve enjoyed over the years, routes that will not deter any hillwalker of reasonable fitness, but outings that blessed me richly at the time, even though I was on my knees at the end of several of them.

Rois-Bheinn June 1981

Superb examples of all that is good about the Corbetts, the Scottish hills between 2500 and 2999ft, are to be found amongst the rocky bluffs and rugged landscape of the Moidart peninsula. These lower hills begin more or less at sea level, and provide good, hard days that would be worthy of the higher Munros. This route is only ten miles in length but the amount of up and down makes it a pretty tough challenge.

There are no footpaths to speak of in Moidart, and no three-thousand footers, which means no erosion paths, no lines of cairns, no roadside car parks and few people. There are however, ten fine Corbetts. Five peaks rise from a horseshoe-shaped ridge that dominates the north-west corner of the peninsula, and three of those are Corbetts. Sgurr na Ba Glaise (874m/2884ft), Rois-Bheinn (878m/2897ft) and An Stac (814m/2686ft) are the highest points on the ridge that curves around Coire a’ Bhuiridh, the yellow corrie, just south of Lochailort.

These hills were my birthday treat a number of years ago. I camped on the shores of Loch Ailort where I was entertained by one of the most stunning sunsets I’ve ever seen. The dying sun set over the Cuillin of Rum in a burst of yellows and reds and, within moments, the waters of the sea loch were running blood red. I lay on the shore in a shimmer of primroses and violets with a glass (okay, a mug . . .) of equally blood-red wine, the toast of heroes, and drank to Fionn MacChumhaill, Ossian, Diarmid and all those warriors of legend who passed the enchanted loch on their final journey to Tir nan Og. It was a good omen.

I’ve never returned to these hills, partly because the day that followed was well nigh perfect and I’ve never wanted to break its spell, one of the finest days the Corbetts have to offer.

A farm track runs in an east-north-east direction from Inverailort to cross a burn that foams and splutters from the low bealach between the hillock of Tom Odhar and the north-east ridge of Seann Chruach. Follow the footpath through the col and onto open moorland beyond where the Allt a’ Bhuiridh chuckles down from the corrie above. Cross to the east bank of the river and climb the western slopes of Beinn Coire nan Gall, heading towards the bealach between it and Druim Fiaclach. From the bealach climb to the summit of Fiaclach by its steep north ridge. Druim Fiaclach is made up of two long and narrow ridges. The best route lies along the south western one where you can enjoy the airy spaciousness, with far-flung views in every direction and where you can gaze down into the depths of its great, wide-open southern corrie. From here the route rollercoasters up and down, along broad, then narrow, sections of ridge. Ahead lie the big climbs up onto Sgurr na Ba Glaise, the peak of the grey cow, and the highest hill of the day, Rois-Bheinn itself. From Sgurr na Ba Glaise, descend the steep slopes that lead down to a wide col, the Bealach an Fhiona. From here an ancient dry-stone wall follows the steep and very rocky slopes of Rois-Bheinn to its eastern summit and trig point.

The views are fantastic, out west along the length of Loch Ailort to the open sea where the isles of Eigg and Rum dance on glistening waters.

By the time you return to the Bealach an Fhiona you will be even more aware of the great lump called An Stac (814m/2671ft), which effectively blocks your homewards route. Its ascent involves more steep and rocky slopes, the steepest yet and the longest too, a good pull of a thousand feet at the end of what has already been a strenuous day.

From the summit descend north, then north-north-east down rocky slopes to Seann Cruach, then down its north-east ridge to the woods above the Tom Odhar col. Descend through the woods to the col and make your way back to Inverailort.

Sgurr Eilde Mor, Binnein Beag & Binnein Mor, Mamores, August 1989

After the horrors of monsoon rain with its associated landslips and blocked roads it was great to see the weekend arrive with wall-to-wall sunshine. As I made my way up the stalkers’ path above Loch Eilde Mor, I couldn’t help recall some of the landslips I had seen over the years. Most vivid was an experience in the Hindu Kush of Pakistan where, following forty-eight hours of heavy rain, a great brown river of mud, soil and rocks swept past our campsite with only yards to spare. Closer to home, in the Cairngorms, another swept down a steep corrie wall bringing with it boulders the size of a car. I fervently hoped not to see another today in the Mamores.

I was certainly aware of how waterlogged the ground was. It was more like spring after a big snowmelt than high summer, and the loch below Sgurr Eilde Mor was full to overflowing when normally, at this time of the year, it shrinks in size. Possibly I was being slightly paranoid because, as I wandered past the still waters and saw the dumpy peak of Binnein Beag ahead, my fears evaporated and I began to enjoy the wonderful situation of the hills at the eastern end of the Mamores ridge.

Sgurr Eilde Mor (1010m/3314ft), Binnein Beag (943m/3094ft), and Binnein Mor (1130m/3707ft) form a trio of peaks that surrounds the great corrie that drains north to Tom an Eite at the head of Glen Nevis. Views from all three summits are far-reaching with the open expanse of Rannoch Moor to the east and a whole cluster of high peaks to the south, west and north with the massive bulk of Ben Nevis dominant, crouching as it does over the curving outline of the Carn Mor Dearg Arete.

The stalkers’ path descends slightly from Loch Eilde Mor before climbing onto the broad bealach that separates the two Binneins. I hadn’t bothered with Sgurr Eilde Mor today, wanting to get high on Binnein Mor to grab some photographs of the ridge and, in turn, to climb Binnein Beag to get photos of Binnein Mor, the shapeliest of all the Mamores peaks.

I wasn’t disappointed. From the summit Ben Nevis looked close enough to touch although, despite its dominant bulk and presence, it didn’t compare to the beautifully sweeping ridges of Binnein Mor whose tiny square-cut summit is formed by curved ridges and corries into a classic, archetypal mountain shape with sparkling lochans filling its corries. I climbed past them, traversing the hill’s north-west slopes to reach the north ridge, a long, narrow highway to an impressively narrow summit with barely enough room for the cairn.

From here another long ridge swept away to a subsidiary summit, then flowed on in a graceful curve to the double-topped Na Gruachaichean, the maiden. The other tops of the Mamores piled up against one another and layer after layer of mountain skyline rolled on into the sun-kissed west.

A broader ridge carried me down to Sgurr Eilde Beag where a wonderfully engineered stalkers’ path dropped to the outward path from Kinlochleven. Away in the south dark clouds were building up and the paranoia returned. Could this be the next storm moving in from the Atlantic? Only time would tell.

Ladhar Bheinn, Knoydart May 1995

Exactly 150 years ago, factor James Grant and his henchmen, under orders from Josephine Macdonnell of Glengarry, began tearing down the thatched cottages and killing the livestock of the cotters who lived on the shores of Loch Hourn and Loch Nevis in Knoydart. The Macdonells of Glengarry had run up huge debts and the Knoydart folk were forced to take up an offer of paid transport to the New World so the family could sell the land.

The flockmasters soon took over with their black-faced sheep and, when that became uneconomical, the entire peninsula was given over to deer stalking. Knoydart became a man-made wilderness.

As we tramped along the shore of Loch Hourn last week the ghosts of the past were still present in the low-walled remains of Skiary, by the little sanctuary of Runival and in the roofless church at Barrisdale Bay. On the tidal burial-isle of Eilean Choinnich tiny shards of granite were all that remained of the gravestones. Only the high tops offer redemption from the past and Ladhar Bheinn, Knoydart’s highest, is symbolic of a new era in Knoydart’s history.

In 1987 the mountain was bought by the John Muir Trust, a conservation organisation that took a leading role in the eventual community buyout of Knoydart, reversing history by putting the future of the area firmly back into the hands of the folk who live and work there. Ladhar Bheinn (1020m/3346ft) is also symbolic of those ingredients that make west highland hills so special.

The most westerly Munro on the mainland, it offers exceptional sea views to the islands of the west and the blend of sea and mountain air is intoxicating. A big hill with a complexity of corrie and ridge, Ladhar Bheinn can be climbed from several directions: from Folach in Gleann na Guiserein, by Coire a’ Phuill from the Mam Barrisdale or by the magnificent Coire Dhorcaill. Having climbed it by all directions I’d recommend the latter route, after the seven-mile lochside preamble from Kinloch Hourn.

There’s a good bothy at Barrisdale, where the estate charges a couple of quid a night for a dry shelter with light and a flushing toilet. Alternatively, you can camp outside.

Just beyond the bothy a wooden bridge crosses the river and a well-used track runs off across salt flats to a stalkers’ path that climbs to the shoulder of Creag Bheithe, before turning south-west into the lower reaches of Coire Dhorcaill, a magnificent bowl that’s partly enclosed by the subsidiary peaks of Stob a’ Chearcaill and Stob a’ Choire Odhar. Between these tops lies a horseshoe of ridges and peaks that makes a fabulous, high mountain walk, but unless you’re experienced on steep, dangerous terrain avoid Stob a’ Chearcaill. The rocky slopes of this top can be lethal when wet.

The Druim a’ Choire Odhair forms the north-west boundary of Coire Dhorrcail and can be reached by a steep and relentless climb from the corrie floor. The ridge then rises comparatively gently in a series of rocky peaks, each eyrie outlook confirming upward progress above the fjord-like Loch Hourn far below.

As the ridge gains height it narrows appreciably, ultimately to its own top, Stob a’ Choire Odhair. From here a scythe-shaped ridge links to the summit ridge, with a fairly steep but easy scramble up the final few feet. The summit is on the west-north-west ridge just a short distance from this junction.

Experienced scramblers will follow the corrie rims right round to Stob a’ Chearcaill where the top’s north-facing slopes offer a tricky descent, but others are advised to follow the corrie rims down to the Bealach Coire Dhorrcail, round the head of another steep corrie before the junction with the long Aonach Sgoilte ridge, and down to another bealach before Stob a’ Chearcaill. From here grassy slopes drop to the summit of the Mam Barrisdale from where a good track takes you back to Barrisdale. Bear in mind when planning that Barrisdale is seven miles from the car parking area at Kinloch Hourn and the walk from Barrisdale up and over Ladhar Bheein is another nine miles. A big day indeed if you don’t stop over at Barrisdale.

Luinne Bheinn and Meall Buidhe, Knoydart July 1995

A few weeks ago I wrote glowingly of the seven-mile trek alongside Loch Hourn to Barrisdale in Knoydart from where most folk climb Ladhar Bheinn, the most western Munro on the mainland. The bothy at Barrisdale is used increasingly to access two other Knoydart Munros, Luinne Bheinn and Meall Buidhe.

I know from speaking to many Munro-baggers that they are often faced with something of a dilemma when considering the best approaches to these two hills. If you want to make a good weekend of it, with a long and glorious walk-in, the Barrisdale approach is best, both scenically and aesthetically. The alternative is to catch the 10.00am ferry from Mallaig, which gets you to Inverie in Knoydart at 11.00am, climb the hills, and return to Inverie for an overnight stay, returning to Mallaig next morning.

Luinne Bheinn and Meall Buidhe, along with Ladhar Bheinn, are the big hills of Knoydart. The first two rise from extremely rough and rocky corries and are separated from Ladhar Bheinn by the high pass of the Mam Barrisdale. A good track, which runs all the way from Inverie to Barrisdale, crosses the pass, the summit of which gives excellent access to the north-west ridge of Luinne Bheinn (939m/3081ft).

Although I personally prefer the Barrisdale route the southern one from Inverie is probably slightly easier, if a little longer. Meall Buidhe is best accessed from the Mam Meadail, the pass that runs from the Inverie River to Glen Carnoch. It’s a relatively short climb to Meall Buidhe’s south-east ridge, which leads easily to the summit. From the hill’s eastern top, a knobbly, undulating ridge leads roughly north-east to Luinne Bheinn and from there it’s only a short descent to the summit of the Mam Barrisdale and the track that runs all the way back to Inverie. It’s a distance of seventeen to eighteen miles.

The route from Barrisdale is considerably shorter, but Barrisdale is, of course, seven miles from the roadhead at Kinloch Hourn. A track runs to the summit of the Mam Barrisdale, and easy slopes climb east onto the Bachd Mhic an Tosaich, from where the ridge to Luinne Bheinn both narrows and steepens in a rough and rocky climb to the summit ridge. A lower, muddier path has evolved in recent years, which follows a line of old fence posts onto Luinne Bheinn’s south-west ridge, a path that’s better used in descent, but I’ll come to that in a moment.

It’s interesting that the name Luinne Bheinn has been translated as meaning the hill of anger, or the hill of melody, or even the hill of mirth – an emotional mountain apparently. I think it was Hamish Brown who suggested it should just be the hill of moods. The summit sits proudly at 939m/3080ft, with a long ranging view down the length of Gleann an Dubh-Lochain and out beyond Loch Nevis where, shimmering on a flat sea, lie the contrasting outlines of mountainous Rum and flat-topped Eigg.

At the east end of the summit ridge a steep southern flank drops down to a broad, undulating ridge that forms a back wall to the rugged, rocky corries that lie between the two Munros. This ridge eventually borders the remote and desolate north corrie of Meall Buidhe, and leads to the obviously defined north-east summit ridge. The highest of the two tops is the western one, at 946m/3104ft.

With both summits now bagged, the main problem is how to get back to Barrisdale. If you descend by a southern route, or by any route to the west, you’re faced with another long climb over the Mam Barrisdale. The best return route, I’ve found, involves more climbing but takes you through the remarkably rugged landscape that lies between the two Munros.

Descend Meall Buidhe’s north ridge and make your way gradually north-east, down long rocky ribs into the heart of this wonderfully rough and rugged mountain bowl. A short climb up grassy slopes leads to a pair of high-level lochans and from the second one a long easy angled gully leads back to Luinne Bheinn’s south-west ridge. It’s only a short traverse now to the muddy path I mentioned earlier, and those old fence posts that lead down to the summit of the pass. From there it’s downhill all the way back to Barrisdale.

A’Mhaighdean, Wester Ross August 1997

The poet Milton once referred to ‘wilderness’ as a place of abundance. Gary Snyder, the poet laureate of the American ecology movement, agrees, but with the corollary that wilderness has also ‘implied chaos, eros, the unknown, realms of taboo, the habitat of both the ecstatic and the demonic. In both senses, it’s a place of archetypal power, teaching and challenge’.

The Letterewe Deer Forest between Loch Maree and Little Loch Broom is probably as close to that description as anything we have in Scotland. The north shores of Loch Maree are rich in oak wood and associated undergrowth and the glens are full of wild flowers: orchids, bog asphodel, lousewort and milkwort. Higher up, the quartzite and Torridonian sandstone ridges, crags and tops offer all the challenge Snyder could ask for and at the very heart of this so-called Letterewe Wilderness lies the remotest Munro of all, A’Mhaighdean, the Maiden (918m/3012ft).

The ascent of A’Mhaighdean demands something more than a day trip. You can ride a mountain bike from Poolewe as far as the bothy at Carnmore from where a good path climbs the mountain but there is an argument to suggest it’s better to ease yourself in gently, either from Poolewe by way of Kernsary and the Fionn Loch, or by Dundonell, Shenavall and Gleann na Muice Beag in the north, or from Kinlochewe and Loch Maree.

In a couple of previous visits I’ve climbed A’Mhaighdean as part of a long rosary of Munros from Shenavall: Beinn a’ Chlaideimh, Sgurr Ban, Mullach Coire Mhic Fhearchair, Beinn Tarsuinn and then A’Mhaighdean and its close neighbour, Ruadh Stac Mor. That’s certainly a big, big mountain round.

This time though, I wanted to combine A’Mhaighdean with other aspects of this Letterewe deer forest: the marvellous oak woods of Loch Maree where there was once a thriving iron smelting industry, the cathedral-like grandeur of the Fionn Loch below the steep crags of Beinn Airigh Charr, Meall Mheinnidh and Beinn Lair and the empty quarter around lonely Lochan Fada before returning to Kinlochewe above the narrow gorge of Gleann Bianasdail.

It turned out to be a memorable outing, even if the three mile walk along the trackless shore of Lochan Fada was tougher than expected, but the undoubted highlight was the ascent of A’Mhaighdean from Carnmore. Although a superb stalkers’ path traverses across the steep slopes of Sgurr na Lacainn and makes its tortuous way up the mountain’s north-east corrie we chose to scramble up the steep, stepped north-west ridge. The stalkers’ path took us as far as Fuar Loch Mor from where we skirted the loch’s western bank and took to the rock. There was plenty of good, steep scrambling but all the real difficulties can be avoided.

In essence, this was a stairway to heaven, a heaven with some of the best views imaginable, arguably the finest in the country, out along the length of the crag-fringed Fionn Loch to Loch Ewe and the open sea. To witness such a view, with the western sun sinking beyond the Hebrides in a riot of colour, is heaven indeed.

Maoile Lunndaidh, Wester Ross October 1998

It’s as though one of the lumpen Cairngorms has been transported to the Achnashellach Forest and dumped alongside the west’s more ‘pointy’ peaks. Maoile Lunndaidh (1007m/3304ft) is one of Scotland’s most remote Munros and would be well at home above the Braes o’ Mar or Badenoch. Typical Cairngormian, her flat summit plateau is surrounded by several impressive corries, particularly the steep-sided Fuar-tholl Mor, and as you march across her dome-like plateau you might, for all the world, be striding across the Braeriach plateau.

This impression is probably made more vivid if you include Lunndaidh’s close neighbours, Sgurr Choinnich (999m/3277ft) and Sgurr a ‘Chaorachain (1053m/3455ft) in your day’s outing. Sgurr a’ Chaorachain, in particular, is as well defined as Lunndaidh is rounded, although you could be forgiven for putting this one in the Cairngorm category too. Whatever characteristics they may share, the three can be combined to offer a big challenge of some twenty miles.

A forestry road runs from the hostel at Craig on the A890 (two and a half miles east of Achnashellach) all the way up beside the Allt a’ Chonais and means you can start and finish your day by bike. Ride as far as the bridge over the Allt a’Chonais, and pick it up on your way back down. A long freewheel through the forest makes a fine end to the day when the feet are beginning to nip a bit.

If you have the ability to cycle and gaze at the scenery at the same time (I always end in the ditch) then enjoy the massive, rocky face of Sgurr nan Ceannaichean as it frowns down on you. The mountains in front are Sgurr Choinnich and Sgurr a’ Chaorachain, divided by a steep col. While you could cross the river at Pollan Buidhe and climb up through the rough corrie to the col, a more satisfying route follows a footpath south-west to the Bealach Bhearnais to where Sgurr Choinnich’s west ridge can be picked up. Climb this ridge, which becomes increasingly rocky as you ascend, to the narrow, level summit ridge.

Now head south-east along and drop down for a short distance in the same direction before turning west-north-west where the corrie edge is followed down to the col below Sgurr a’ Chaorachain. Follow the ridge directly to the summit where you have a choice of route – you can either continue east to Bidean an Eoin Deirg, which can be descended steeply north-north-east to a col at about 600m, or descend off Sgurr a’Chaorachain’s north ridge for half a kilometre before turning north-east onto the Sron na Frianich above the waters of the dark Lochan Gaineamhach. Drop down the eastern slopes of the Sron to the bealach and its many peat hags.

To continue to Maoile Lunndaidh, climb the long western ridge of Carn nam Fiaclan and follow the narrowing neck of ridge between the head of the impressive Fuar-tholl Mor in the north and Toll a’ Choin in the south, to the huge, gravelly plateau of Maoile Lunndaidh.

Once you’ve found the summit cairn, a dodgy operation in misty conditions, drop down the broad heather-covered slopes of the north ridge into Gleann Fhiodhaig just east of the ruined Glenuaig Lodge. Follow the track back to the Allt a’Chonais and that long promised downhill bike ride back to the start.

The Talla Bheith Corbetts, Perthshire November 2002

The track that runs the length of Coire Dhomhain through the hills of the Dalnaspidal Deer Forest normally provides a pleasant approach to the Munros of Sgairneach Mhor and Beinn Udlamain. Today it was leading me into low cloud and snow showers.

I was heading for the Corbetts of Stob an Aonaich Mhoir (855m/2821ft) and Beinn Mholach (841m/2775ft), two of the least visited hills in Scotland. While both summits can be tackled independently via tracks from Loch Rannoch-side in the south I thought I’d take two days to climb both, camping out overnight in one of the emptiest quarters in Scotland.

The Scottish Mountaineering Club Guide to the Central Highlands is not very flattering to either hill. In the eleven lines that describe the route to Beinn Mholach the guide manages to say virtually nothing about the hill itself, although it does say it lies in the heart of a wasteland’. It doesn’t say much more about Stob an Aonaich Mhoir, but does tentatively suggest that this area of the Talla Bheithe deer forest between Loch Garry and Loch Ericht ‘will attract only the confirmed seeker of solitude’.

This area of rounded hills and shallow glens is certainly pretty desolate, particularly on a dour mid-November weekend when low clouds and frequent snow squalls cut visibility to less than a hundred metres.

It’s often when expectation is at its lowest that the mountain magician creates beauty out of nothing. Descending a narrow, steep-sided glen into Coire Bhachdaidh I looked up to see the cloud suddenly lift and expose a marvellous scene. A sinuous stream, sparkling in the sudden light, twisted its way down the length of the corrie all the way to a white house, Coire Bhachdaidh Lodge, on the shores of Loch Ericht. Beyond the dark waters the hills of Ben Alder Forest were bathed in mellow sunshine.

The real bonus was that I could now see my first top and was soon climbing snow-covered slopes to its summit, perched precariously above the steep crags that drop into Loch Ericht. Old Rannoch tales claim that a village was once drowned in the waters of the sixteen-mile-long loch. Apparently, a great earthquake caused a cataclysmic rush of water to submerge the parish of Feadaill at the south end and all its inhabitants perished. Local folk say that on a still day you can see the steeple of the church below the surface of the water.

Beinn Mholach lies south-east of Stob an Aonaich Mhoir, five miles of bog-trotting over a shallow, waterlogged pass to the upper reaches of the Allt Shallainn. From the headwaters of the burn it was a fairly straightforward climb over heather slopes to Mholach’s rocky summit, but it was dark by the time I reached the big summit cairn. Too high to camp I had to descend to the river and find a campsite with the aid of my head torch.