Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

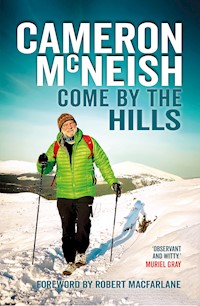

'Observant and witty.' -Muriel GrayIn Come By The Hills Cameron McNeish shares his journeys through Scotland on foot, by bike and in his wee red campervan. He is still an adventurer, but these days things are a bit different. Reaching summits is still enjoyed, but no longer a priority. Instead, he takes us on a wide exploration of Scotland's hills, forests, and coastlines, and the ancient tales that bring a turbulent history to life. He takes us into the loveliest of glens, Etive and Lyon, to our most distant islands in the Hebrides and Shetland, and reminisces on wonderful characters such as Dick Balharry, Finlay MacRae, and the early working-class climbers when they first took to the hills.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 491

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Cameron McNeish

Highland Ways (KSA)

The Spurbook of Youth Hostelling (Spurbooks)

The Spur Master Guide to Snow Camping (Spurbooks)

Backpacker’s Scotland (Robert Hale)

The Backpacker’s Manual (Nordbok)

Ski the Nordic Way (Cicerone Press)

Classic Walks in Scotland, with Roger Smith (Oxford Illustrated Press)

The Munro Almanac (NWP)

The Corbett Almanac (NWP)

The Best Hillwalking in Scotland (The In Pinn)

The Wilderness World of Cameron McNeish (The In Pinn)

The Munros, Scotland’s Highest Mountains (Lomond Books)

Scotland’s 100 Best Walks (Lomond Books)

The Edge – One Hundred Years of Scottish Mountaineering, with Richard Else (BBC)

Wilderness Walks, with Richard Else (BBC)

More Wilderness Walks, with Richard Else (BBC)

The Sutherland Trail, with Richard Else (Mountain Media)

The Skye Trail, with Richard Else (Mountain Media)

Scotland End to End, with Richard Else (Mountain Media)

There’s Always the Hills (Sandstone Press)

First published in Great Britain

Sandstone Press Ltd

Suite 1, Willow House

Stoneyfield Business Park

Inverness

IV2 7PA

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored or transmitted in any form without the express

written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Cameron McNeish 2020

Editor: Robert Davidson

The moral right of Cameron McNeish to be recognised as the

author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-913207-28-1

ISBNe: 978-1-913207-29-8

Jacket design by Raspberry Creative Type, Edinburgh

Ebook compilation by Iolaire Typography, Newtonmore

Contents

Acknowledgements and Dedication

List of Illustrations

Foreword by Robert Macfarlane

Introduction

1. The Pull of the Hills

2. Ecology of the Imagination

3. The Longest, the Loveliest and the Loneliest

4. To Know Being, the Final Grace

5. Spirit of the Spey

6. The Bridge and the Blackmount

7. The Heartland

8. Loveless Loveliness

9. Through the Gates of Affric

10. Strumming the Heart Strings

11. Northness

12. Beyond the Shining Seas

13. Islands on the Edge

14. A Place Apart

Acknowledgements and Dedication

Given that climbing hills and exploring Scotland’s wild places are such solitary pastimes, there is a surprisingly large cast to thank for their contributions, intended or otherwise, to the writing of this book.

The title, Come by the Hills, was first the title of a song that I and many others, including the celebrated duo that were The Corries, and Finbar and Eddie Furey from Ireland, have been singing for decades. It isn’t, as many imagine, a traditional song but the work of the late W. Gordon Smith. It’s a song of hope and vision, as I hope this book will be.

A list of all the people who have walked and climbed the Scottish hills with me over the years would fill these pages, so I will just mention a few who have been particularly influential in my thinking about the wild places of this great country of ours. Special thanks go to Roger Smith, Jim Perrin, Chris Townsend, Hamish Brown, Jim Crumley, John Manning, Tom Prentice, John Lyall, Paul Tattersall, Bob Telfer and John Hood. For sharing some great cycling adventures in recent years, many thanks to my lifelong pal Hamish Telfer.

Hearing the stories of fellow adventurers has always been inspirational to me and I wish to thank those who have contributed with their own words of wisdom: Laurence Main, Dennis Gray, Robert Macfarlane, Julie Fowlis, David Craig, Alan Riach, Llinos Proctor, Jimmy Marshall, Ian Mure, the late Dick Balharry, Donald Fisher, John and Marie Christine Ridgway, Duncan Chisholm, John Ure, Iain and Willie Grieve, Dr Margaret Bennet, Lee Craigie and Paul Tattersall.

Television has played a big role in my life in the past quarter century and I want to thank Richard Else, Margaret Wicks, James Else and Kate Hook of the Adventure Show Production Company for their enduring patience and friendship. There can’t be many television presenters who have worked with the same production company for their entire career. Many thanks go also to David Harron, our Executive Director at BBC Scotland, for his continued support and personal friendship.

Presenting a television show is only a small part of what is always a team effort and I’d like to give special thanks to the guys who do their best to make me and the Scottish landscape look good, our camera operators: Paul Diffley, Simon Willis, Ben Pritchard, Andy McCandlish, Dominic Scott, Keith Partridge and Chris McHendry. These are the guys who stand around in the wet and cold, or in the snow, while I blether with guests, the guys who follow me up hill and down dale carrying heavy cameras and tripods, never complaining. Well, not very much.

I’ve also been greatly encouraged by the editors and publishers of the magazines I write for so thanks go to Darren Bruce at Newsquest, Paul and Helen Webster at Walk Highlands, Robert Wight and Garry Fraser at the Scots Magazine, Emily Rodway, formerly at the Great Outdoors magazine, Joe Pontin at Countryfile magazine and Geneve Brand at Campervan magazine. A special thank you to those editors who gave me permission to re-use or re-write various pieces that have previously appeared in their titles.

Also, a very special thanks to the team at Sandstone Press. I’m really thrilled to be working with such a top-notch international publishing house that is based here in the Scottish Highlands, and I very much appreciate the help and wise counsel offered by fellow Munroist Robert Davidson. To have a publisher and editor who is also a hillgoer is a huge bonus for anyone writing about Scotland’s wild places.

A huge thanks to award-winning author, mountain man and longtime friend Robert Macfarlane for kindly taking time from his busy academic life to write the foreword to this book. I clearly recall Ted Peck, his grandfather, proudly telling me about the young Robert and his love for the Scottish hills. What Ted didn’t know was that his grandson was to become one of our most influential and wise environment commentators. I’m proud his name graces the cover of this book along with my own.

Finally, my life as an outdoors writer and television presenter wouldn’t have been possible had it not been for the support and encouragement of my two sons, Gordon and Gregor, and their own support teams, Hannah and Sarah. My two granddaughters, Charlotte and Grace, are a constant source of joy. The work I have done and still do, the writing, television appearances and everything else, wouldn’t have been possible without the consideration, understanding and endless support of my wife of almost 50 years. This book is dedicated to Gina.

Cameron McNeish

Newtonmore, 2020

List of Illustrations

SECTION ONE

Winter, a good time to take the longer viewBen Starav, fabled land of Deirdre of the SorrowsOn Quinag, one of the finest hills in the glorious North-WestApproaching the summit of The Wiss, above St Mary’s LochOn The Schill, Scottish BordersThe summit of the Eildons, formed by the De’il himsel’The Three BrethrenLaurence Main, guidebook author and DruidThe Praying Hands of Mary in Glen LyonThe Tigh nan Bodach, Glen CaillicheThe east ridge of Schiehallion, Loch Tummel in the backgroundLoch Avon, the jewel of the CairngormsWalking into the Northern Corries of the CairngormsGina at the summit of Ben RinnesDavid Craig, river guide on the SpeyCraig Dubh at Jacksonville, left to right: John McLean, Ian Nicholson, Jimmy Marshall, me, and Tam the BamBuachaille Etive Mor, the epitome of fine mountainsBelow Na Gruagaichean, in the MamoresThe North Face of Ben Nevis, Bill Murray’s winter hauntPath repairs on the Ben above Glen NevisWith Bill Murray at his home in LochgoilheadA frosty Glen AffricDick Balharry in his elementThe winter cliffs of Coire ArdairTaking time to ponder at Rowchoish bothySECTION TWO

Enjoying the peace of the pine woods in RothiemurchusNear the summit of Beinn Fhada, KintailOn Sgurr nan Spainteach, Five Sisters, above Glen ShielThe Falls of GlomachThe regeneration of the Caledonian pine forest, Glen AffricThe SYHA hostel at Alltbeithe, Glen AffricComing third in the Battle of the Beards to Dick Balharry and Adam WatsonOn Beinn Eighe, TorridonKay and John Ure of the Ozone Café, Cape WrathDuncan Chisholm, one of Scotland’s finest traditional fiddlersMarie Christine and John Ridgway with their Lifetime Achievement awardsThe gloriously atmospheric Sandwood BayA beehive shelter on HarrisA glorious beachside camp on HarrisThe quiet glory of HushinishThe atmospheric standing stones at Callanish, Isle of LewisA Shetland sunset from EshanessMuckle Flugga and Out Stack, Britain’s most northerly islandsLifting my beloved campervan onto the pier at North RonaldsayThe tombola connecting St Ninian’s Isle to Shetland mainlandApproaching the summit of Ben GulabinContemplating the Craigallion Memorial and all it means to meThe graveyard at Blackwater DamPaul Tattersall, first person to take a mountain bike over all the MunrosFun is to be had in the hills, even when the years wear onForeword

by Robert Macfarlane

One of the first times I heard the name ‘Cameron McNeish’ was from my grandparents, who lived on and off for thirty years in an old forestry cottage near Tomintoul, perched above the River Avon where it rushed towards its flood-plains from the Cairngorm plateau. My grandparents were mountain-people; they’d spent their lives climbing and exploring from the Alps to Mount Kenya, from the Rwenzori to the Himalayas. The Cairngorms was their heartland, though — and along with Cameron they were part of the early resistance to the ill-conceived construction of the funicular in the Northern Corries.

My grandparents were then, as Cameron is now, into their eighth decade, but age hadn’t dimmed the light of their love for the hills. As Cameron shows here, slowing down can also mean sharpening up. So it was with them. Grandad still got out on his old wooden touring skis, as tall as him and about half as heavy (they’re now in the National Museum of Scotland), and we still made our multi-generational ascents of Lochnagar and Cairn Gorm, foraged blaeberries and swam in the deep brown river-pools of Glen Feshie. My grandmother was a superb botanist, especially good on Alpine flora, and I remember my childish frustration at her gradual pace mingling with my surprise at her knowledge of the plant-life that surrounded us. ‘What do you mean, you can’t recognise a gentian!?’ she once reprimanded me, in genuine (and rightful) horror.

I grew up with Cameron’s writing and programme-making. I watched him cover the miles and the peaks on television, amazed at the landscapes he was unfolding for me and millions of others. Grandad would post me clippings of Cameron’s journalism, and on my twentieth birthday I was given a copy of his The Munros. It became, along with the SMC Hillwalkers’ Guide, my companion to the Highlands. It still is. For the past quarter-century, really, Cameron’s been an ageless and indestructible figure in my imagination: an unstoppable force, shaking sense into public debates over land use and mountain culture, climbing top after top, writing and fighting for the good and the wild.

In one way it’s been unsettling to read Come by the Hills, and to learn that this Scottish superhero is somehow human after all, subject to aches and limps, strapped to the ‘dying animal’ (Yeats’s phrase) of the mortal body like the rest of us. There’s a painful honesty to the experience of ageing here, and to the geographical limits that are imposed by becoming a bodach nam beinn, an ‘old man of the hills’. But what rings far louder than regret is his joy – sheer bloody joy – in the mountains and what they give to us. There’s a passage early on where he describes nearly abandoning hill-climbing because the discomfort of movement is too great. But then he feels a far greater pain: ‘a feeling of loss . . . like bereavement’, caused by the idea of losing his ‘love of mountains and wild places’. That struck straight to my heart — it is impossible, really, to imagine living without the hills. So, what is needed with older age is a moderation of ambition, a changing of scale. Which is of course, in its own way, a turn back towards the wonder-years of childhood, when the height of a mountain is irrelevant, and when as much amazement can be found on the bank of a burn or a forest floor as up on the ridges and peaks.

Early on, Cameron quotes the great Alastair McIntosh on the ‘ecology of the imagination’; a way of thinking of the world that leads both inwards to specific detail and outwards to a webwork of connections. These chapters partake of that imaginative ecology. They blend natural history, folklore, geology, topography, community and literature, understanding that what we call ‘landscape’ is always a weave of many strands, an irreducibly complex texture of human and more-than-human histories. So it is that these ecumenical essays are open to plurality of several kinds, and celebrate a version of Aldo Leopold’s ‘land ethic’ – which extends the notion of a region’s ‘community’ to include creatures, soil, water, rock and air – without shying away from the hard work involved in improving landscapes for people and for nature. Romanticism and pragmatism for once make good partners here.

Come by the Hills is also a testimony to the many folk who have shaped Cameron’s path in life, including the mountaineer-writer W. H. Murray, the climber Syd Scroggie, the folk-singer and story-collector Hamish Henderson, and Cameron’s wife Gina. One of the most moving chapters is Cameron’s tribute to the inspirational conservation pioneer Dick Balharry, who I remember telling me in my early twenties to hold fast to a definition of ‘wild land’ in Scotland as that which gives safe home to golden eagles (still a good rule of thumb, I’d say). Cameron writes of how Dick changed minds, won hearts, put backs up, and transformed landscapes: ‘Dick articulated his love of the outdoors in such a way that it touched others, enthused them and changed their lives’. Well, Cameron too has unmistakably done this — though he’d never claim as much himself.

Above all, though, this book is a late-life love letter to the hills, sent from the glens. Again and again come moments that will be recognisable to anyone who loves the Scottish mountains: the ‘shudder of wonder and awe’ that passes through Cameron whenever he enters Glen Coe, the ‘gnawing realisation of what is important’ when he is in wooded Glen Affric. ‘Mountain and wildness settle peace on the soul’, he writes late on, ‘It’s a wonderful phenomenon and doesn’t need any help’. Reading this fine book — with its sense of the infinite capacity of mountains to give to those who love them, I was frequently reminded of lines from the end of Nan Shepherd’s slender masterpiece about the Cairngorms, The Living Mountain.

However often I walk on them, these hills hold astonishment for me . . . There is no getting accustomed to them.

Robert Macfarlane

February 2020

Introduction

After a lifetime of climbing mountains and exploring wild places, the arrival of my greybeard years meant a change of direction and focus for me. The biblical ‘threescore years and ten’ meant not only slowing down and a growing creakiness in the joints, but also a new awareness of my own mortality. That awareness fostered an element of resolve, and a determination to focus more sharply on the things that are important to me, the many things I can still do. I’m very reluctant, just yet, to exchange my boots for a pair of slippers.

Although the ageing process has robbed me of the physical fitness I enjoyed in earlier years, I can still creak my way over the hills, and a slower pace brings its own benefits. It allows me to look around and observe the things I missed when hitherto I would impatiently strive for the summit. It’s worth remembering the words of the poet William Henry Davies, no matter what age we are.

What is this life if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

No time to stand beneath the boughs

And stare as long as sheep or cows.

No time to see, when woods we pass,

Where squirrels hide their nuts in grass.

No time to see, in broad daylight,

Streams full of stars, like skies at night.

No time to turn at Beauty’s glance,

And watch her feet, how they can dance.

No time to wait till her mouth can

Enrich that smile her eyes began.

A poor life this if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

A few minutes here and there, sitting on a rock, allows me to ponder the moment and to wonder with renewed astonishment at the beauty around me: the moss campion that clings to life on the bare screes of our highest hills, the joyful sound of a skylark and the often breathtaking drama of a far-flung view.

The ‘pull of the hills’ has never diminished, and I regard it as a sort of gravity for the soul: my anchor, and the foundation from which I have created a kinship that has stood me in good stead when the world has occasionally appeared a little darker. The exercise, the beauty, the simplicity and drama, all combine for the good of our mental and physical health, and the sounds, the smells, the air like wine, the textures of the trees and rocks serve to increase not only my awareness but also the sheer joy at being in and amongst Scotland’s beautiful places.

The song from which this book takes its name includes the line, ‘Come by the hills to a land where fancy is free.’ That little phrase suggests to me places and landscapes that allow my imagination full expression, to remember times past and hope for a better future. It encourages me to cast aside the prejudices and preconceptions of a working-class Presbyterian upbringing and consider the far-reaching influences of our Celtic past, and how our ancestors’ reverence for wild landscapes can influence us in the future.

Unlike my autobiography, There’s Always the Hills, this new book is not especially about me. Come by the Hills is littered with conversations with people who have inspired and encouraged many of us, who bring a new slant of appreciation to those places we all hold dear.

On foot, by bike and in my wee red campervan, Come by the Hills is an exploration of Scotland in which reaching mountain summits is still enjoyed, but is no longer a priority. It’s an exploration of the wider Scottish landscapes: hills, forests, coastlines and glens, and those ancient tales and legends that extend our knowledge of Scotland’s turbulent history. Most of all, I hope Come by the Hills will be an inspiration and spur to those outdoor folk who suspect their best years are behind them.

1

The Pull of the Hills

Ben Starav isn’t the tallest mountain in Scotland, but you have to earn every inch of its height. Climbing from the shores of Loch Etive to the mountain’s square-cut summit ridge is long and relentless, a brutal ascent by any standard, but that severity is the mountain’s saving grace. The steep slog makes you stop at frequent intervals and, when you do, the views simply take your breath away, should you have any to spare. There’s little respite as it rises in grassy steps from the headwaters of the sea-loch to the upper reaches of the rocky Coire da Choimhid. Recently, I climbed it on a still autumnal day, with stags roaring from the inner recesses of the corries and other beasts answering across the glen. Water from overnight storms poured from the higher slopes like a thousand wriggling snakes, and curtains of clouds sporadically hid the higher reaches of the mountain.

At the top of the corrie, on my first glimpse of the loch, I recalled the tale of Deirdre of the Sorrows, one of the great legends of grief and loss in Celtic literature. Deirdre was a first century Pictish princess who was betrothed to Conor, the High King of Ulster, before fleeing to Etive-side with her lover, Naoise, one of the three Sons of Uisneach. Celtic tales tell of her delight in these hills, where she lived a content and happy life in the company of her lover and his warrior companions.

After some time, a messenger arrived from Ulster. Conor desired the return of the Sons of Uisneach to help him repel the invading forces of Connaught, promising them a warm welcome and forgiveness. Deirdre was fearful and suspected treachery, but Naoise and his brothers, born to the thrill and excitement of battle, were excited by the prospect of returning to Ulster. In contrast Deirdre was heartbroken at having to leave her beloved Alba, a passion that’s easy to understand.

By now the wind had rent great holes in the cloud cover and sunshine illuminated the views. At the top of Glen Etive stood the twin herdsmen of Etive, Buachaille Etive Beag and Buachaille Etive Mor, the Pollux and Castor of Rannoch. To their left the Bidean nam Bian massif appeared as a steep, jagged swell of hills. Across the fjord-like sliver of Loch Etive lay Beinn Trilleachan, with a sweep of granite crags falling from its whaleback ridge, crags that are known to rock climbers as the Etive Stabs. When seen, head on, from Starav these boilerplate slabs seem to hang from the mountain like a grey curtain, and they contain some of the most surreal friction climbs in Scotland.

Even after at least half a dozen ascents of this mountain, I’m always taken aback by how far there is still to go from the top of the corrie. The angle of the slope relents for a short distance, but then the ridge narrows to become a mild scramble along an edge of broken crags until the slope rises in a confusion of boulders. The small summit cairn is reached suddenly and without fanfare, and with some relief it has to be said. Cloud swirled around me, but I could discern the gleaming silver slit of the loch far below. It was easy to imagine the war galleys of the Sons of Uisneach gliding down the loch, sails unfurled, banners flying as they faded into a fret of sea-mists below Beinn Cruachan. Their journey was into an unknown and perilous future, the young woman curled up in the stern of one of the galleys, her emotions conflicted and confused, her love for Naoise tempered by a profound sense of loss for the place she was leaving: Etive and her glens, peaks that pierced the sky and her sunny bower above the rocky crags of Lotha.

Inmain tir in tir ud thoir Alba cona lingantaibh Nocha ticfuinn eisdi ille Mana tisain le Naise.

Beloved is that eastern land,Alba (Scotland), with its lakes.Oh that I might not depart from it,Unless I were to go with Naos!

The Poems Of Ossian

For many of us the emotional magnetism exerted by the beauty and challenge of mountains is hard to resist. It eats away at us, fills our hopes and dreams, and harbours our ambitions. In meeting the challenge of the hills, we open ourselves to everything associated with such places: flora and fauna, geology, history and legend, song and spirit of place. Too many of us are unaware of how powerful and enduring that pull can be until we are in danger of losing it, an insight that hit me hard as I approached the cliff-edge of my eighth decade. A series of age-related issues had made me seriously consider giving up. Long descents were particularly painful and on more than one occasion I had serious doubts about whether I would make it home. Several times I told myself that the time had come to bid my farewell to the high tops, but after a few days I would again feel that familiar urge, the need to be among them, as powerful and controlling as any addiction. Unable to resist its power, off I would go, shuffling and limping into the blue upland yonder, another bodach nam beinn, another old man of the hills, reluctant to submit to the inevitability of age and decline.

This addiction first embraced me as a child. On family holidays on the Firth of Clyde I would often gaze across the sea to the Isle of Arran, and soon became infatuated by the shape of the hills, the distant vision of high corries, silver streams and the changing textures of the slopes. To my young eyes Arran was a world away and not a mere dozen miles. On other family excursions I was only really happy when we were close to hills and mountains. Flat landscapes didn’t inspire me, but if there was a rise in the ground, even a dim outline of hills in the distance, I experienced a trembling excitement that made me curiously joyful and upbeat. On one occasion I watched two men descend from a mountain in Glen Coe. Sun-browned and lithe, they wore tartan plaid shirts and breeches and were bronzed by the sun. One of them carried a coiled rope over his shoulders. To my youthful eyes they were like gods come down from Parnassus and, at that precise moment, I knew I wanted to be one of them. Away beyond the path they walked, from the slopes they had descended, the screes and gullies and buttresses that made another world, the domain of ridges, plateaux and summits that belong to the mountain gods. Here was a world as unknown and mysterious as Atlantis and I wanted to discover it.

My first hills were modest: the Campsie Fells, the Luss hills above Loch Lomond and the tumbled braes of the Trossachs, but even on their humble heights I felt the first creeping tentacles of obsession. I was in my early twenties when I gave in, more or less abandoned all other interests and decided I would commit my life to climbing hills and mountains and exploring the wild places of our wonderful little country. It was a decision never to be regretted because it gave me a wonderful career as a writer, magazine editor and television presenter, and the opportunity to travel the world. That career has spanned almost half a century but I’m still acutely aware of the pull of the hills, even though they have almost been the end of me on several occasions. I’ve fallen down crags and been avalanched. I’ve been lost (or at least temporarily misplaced) and suffered hypothermia, so it most certainly is an obsession, but one that is both delectable and fulfilling. I’m still thrilled in the proximity of mountains and still worry myself silly about the day that will inevitably arrive when I can no longer immerse myself in them.

That spectre has hovered over me several times in recent years. Various medical problems, predominantly degenerative issues (medical term for old age) in my feet and legs have threatened to end my hill-climbing days for good. On a number of gloomy occasions, I’ve taken the decision that enough was enough, I couldn’t stand the pain and discomfort any longer, but each time I was hit by such a feeling of loss it was like bereavement. I was terrified at losing the very thing that had driven me for most of my life: my love of mountains and wild places. I can still hobble about the hills, but I am painfully aware that age can rob us of so much and the sense of loss has been profound. Fortunately, medicine and technology have helped to overcome much of the discomfort caused by chronic plantar fasciitis, plantar plate tears, Morton’s neuromas and osteoarthritis in the toes. I can, with some adjustments to pace and effort, still get on the hills. More seriously, I was recently sidelined for almost two years by a torn medial knee ligament. Uphill was hard, but descending was tortuous. My doctor kept telling me to be patient, but patience has never been my strong point.

The problem began as a minor irritant at the end of a great day on Bidean nam Bian. It was the beginning of summer, and skylark song filled the air. Glen Coe was looking at its most glorious as I wandered through Coire nan Lochan and became aware of a slight pain on the inside of my knee. Within a couple of days it reduced to a dull ache, and a couple of weeks later I was back filming for the BBC on the Isle of Arran. We had climbed Goat Fell and took our time, stopping every so often to position the camera and video me delivering a piece to camera. Such is the nature of television work. All went well; we all enjoyed the views of A’ Chir and Cir Mhor across the glen. Unfortunately, things changed dramatically during the descent. Every downhill step was slow and painful, though the situation wasn’t entirely without humour. My producer, Richard Else, who is also qualified to carry a bus pass, was moving equally slowly because of an historic knee injury of his own. Richard’s wife Meg carried the heavy tripod and a load of heavy gear, so she too was moving slowly. As the three of us hobbled down the southern ridge like extras from Last of the Summer Wine a couple of hillwalkers spotted the gear and asked if we were making a film. We said we were and of course the lads asked what it was for? When we answered The Adventure Show it felt hilariously ironic. But age is no respecter of health, and the next morning I found it painful to walk. When sitting down I had to straighten my leg very slowly before it could bear weight; getting in and out of a vehicle was even worse, and my knee was hot and swollen. I’ve been relatively fortunate during my mountain career in terms of injury. I’ve survived an avalanche and several falls but, overall, avoided the normal knee and hip problems.

As a young man I was mad keen on track and field athletics and was a reasonably successful long jumper and sprinter. The training for long jump and triple jump put a lot of pressure on the knees and hips and I shudder to recall doing squats with 200 lbs on my shoulders when I was sixteen. My track career came to a premature end after a series of injuries. More pertinently, the mountains were exerting their pull. That was in youth. More recently, after reaching the grand old age of sixty-five, various problems began to manifest. Nothing that I couldn’t manage, though, and throughout that summer the knee problem seemed to improve.

With my lifelong pal Hamish Telfer, I cycled the length of Ireland, from Mizen Head to Malin Head, and later in the year we cycled the length of the Outer Isles, from Vatersay to the Butt of Lewis, but climbing hills was a very different matter. Each time I attempted something strenuous the knee would give way and I found myself back at square one. I was too stupid to consider resting for any length of time (when you earn a living from climbing hills you can’t afford to be away too long) and the last thing the viewing public want to see is a greybeard presenter as he limps and hirples across the landscape. Eventually the pain became too great and I had to cancel a shoot.

My doctor diagnosed a damaged medial ligament in the right knee, and was backed up by Julie Porteous, my sports physio in Aviemore. The prognosis? It would get better if I rested it for four to six weeks. My doctor suggested that since I had been abusing my body, in the nicest possible way, for over forty years by carrying heavy packs up hills and along trails I should expect a reasonable amount of wear and tear. I responded by reminding him that our forefathers wandered the hills every day of their lives and managed to cope. His answer had a certain inevitability about it: most would have been dead and buried before they reached my age. Touché!

Fortunately, there was some good news amid all this gloom and doom. An X-ray showed no serious problem with the knee joint. No evidence of osteoarthritis and only the usual wear and tear below the kneecap and down the front of the knee. The downside was that a damaged ligament takes a long time to heal, but with proper rest and gentle exercise will get better . . . eventually. I was a little shaken when he told me that if a fit young footballer of only twenty-one came to his surgery with a similar injury he would tell him he was out of the game for six months. I decided to rest.

The doc was right. While holidaying in the Alps my knee suddenly felt better and by the end of the holiday it was only slightly sore at the end of a hill day. Nine months later it had completely recovered. I wished I’d taken my doctor’s advice earlier when, instead of resting the injury, I simply kept the problem recurring. The moral of the story is very simple. Don’t try and live with pain or injury. Don’t try and work through it, pretending it isn’t there, particularly if you are approaching, or actually living in, the autumn of your years. Do something to prevent it getting worse, or you could end up like me with a whole summer wasted.

It took me some time to come to terms with the fact that age has robbed me of the physical fitness I have enjoyed throughout life. It has taken me a long time to get it into my thick brain that I’m no longer capable of multi-day expeditions over the hills and mountains, or complete long days in the hills, and I certainly can’t travel very far with a heavy pack on my back. However, I can still creak my way over smaller hills, and still enjoy shorter days. I’ve become more familiar and appreciative of forest, woodland and coastal walks and now enjoy other aspects of the hill game, like photography and birdwatching. I also cycle a lot. Indeed, I did have thoughts of calling this book ‘There’s Always the Bike’.

Gina and I travel around the Highlands and Islands of Scotland in our campervan, discovering places that we ignored during our mountain days. We visit castles and keeps, explore glens and coastlines, learn of ancient tales and legends and extend our knowledge of Scotland’s turbulent history. We still climb hills when aching limbs and joints allow. This gradual metamorphosis from fit mountaineer to bodach nam beinn, old man of the hills, has paralleled my professional life. I stopped editing The Great Outdoors magazine when I was sixty. Around the same time, my long, televised backpacking trips were replaced by even longer journeys along Roads Less Travelled in a campervan: television shows that saw me walk, cycle and packraft in various out-of-the-way places. I began writing a monthly column for the Scots Magazine, the oldest consumer magazine in the world, which is a milestone in my career. My old friend and mentor Tom Weir wrote his first article for the Scots Magazine in the year before I was born and I now follow in his footsteps.

The magazine’s editor, Robert Wight, asked me recently to read through Tommy’s very first article, published exactly seventy years earlier, and produce a column reflecting on both his skills and how our landscapes have changed. Reading through that very first feature, I found myself taken back decades to when I was possibly the only teenager in the land to possess a Scots Magazine subscription, an unexpected birthday gift. While my peers were buying the New Musical Express and Melody Maker, I was more interested in the monthly stravaigings of a tweed-clad character who magically opened the curtains of my urban upbringing on landscapes undreamt of: hills and mountains, exotic-sounding birds and animals and a hardy population of fascinating people.

Tom’s ‘My Month’ began in 1956 when the editor, Arthur Daw, asked if he’d like to try it for a year. In fact, the monthly column lasted almost fifty years. Arthur’s advice to Tom was simple: get as much variety as you can into the articles. This new commitment came about at an interesting time in Tom’s life, when he was spending much of his time abroad. In 1945 he had become a member of the Scottish Mountaineering Club, of which he later became President. Although he had climbed previously it appears that his performances improved dramatically in the latter years of the forties and throughout the fifties, particularly with partners like Archie MacPherson and Douglas Scott. Inspired by the writings of mountaineer Frank Smythe, he travelled to the Alps where he climbed the Dent Blanche and enjoyed a ski-mountaineering ascent of the Finsteraarhorn in the Bernese Oberland. His Alpine exploits led to inclusion in a Scottish expedition to the Indian Garhwal region along with Scott and two notable mountaineers of the time, Tom MacKinnon and Bill Murray. All three became firm friends for the rest of their lives.

That initial expedition saw success on the 20,000-foot/6,200-metre peak of Uja Tirche. Writing later, Tom remarked, ‘Looking back on it I remember no other mountain day so full of surprises and sustained interest. Weariness fades before the enduring values, the joy of a hard-won summit, and the contentment of spirit in a new appreciation of being alive.’

Attempts were made on several other peaks, but their most notable success was the discovery by westerners of a huge area of the Indian Himalaya, a genuine journey of exploration. Other expeditions followed throughout the fifties: to Arctic Norway with Scott and Adam Watson from Aberdeen; to the Rolwaling area of Nepal (the account of that expedition became a book in 1955, East of Kathmandu); to the High Atlas mountains of Morocco and an area that he later described as his favourite, the Sat Dagh and Cilo Dagh regions of Kurdistan. His final major expedition was with Sir John Hunt (who had led the successful Everest expedition in May 1953) to Scoresbysund in Greenland in 1960. Tom assisted fellow SMC member Iain Smart in collecting and collating data on Arctic Tern populations.

Following that concentrated bout of exploratory expeditions in the fifties, marriage to Rhona and a move to the Dunbartonshire village of Gartocharn saw Tom Weir settle to the life of a freelance writer, informing and entertaining his growing band of Scots Magazine readers while occasionally dabbling in other forms of media like radio and television. He made a series of television ‘shorts’ with producer Russell Galbraith at Scottish Television which were later compiled into longer television features before Weir’s Way was eventually launched, the television series that was to raise Tom to national stardom. No scriptwriters were employed on Weir’s Way or the follow-up series, Weir’s Aweigh, or the series that followed that, tracing the post-Culloden journey of Prince Charles Edward Stuart.

Tom wrote the storylines himself: tales of Rannoch Moor and Glen Coe, historical events and the opening of the West Highland Way amongst others. For me one of the highlights was when he interviewed two of his long-time pals in the glow of a crackling little campfire on the banks of Loch Lomond. Jock Nimlin was a Clydeside crane operator and one of Scotland’s finest climbers, and Professor Sir Robert (Bob) Grieve was, at the time, inaugural chair of the Highlands and Islands Development Board. The three men sat in the glow of the fire and simply chatted about their love of wild places, outdoor politics and their own very different careers. It was a mirror of the Craigallian Fire of the thirties, at which both Nimlin and Grieve had toasted themselves, as had Tom’s other great friend, Matt Forrester. Tom’s first feature, ‘Remotest North,’ was a seven-page description of a convoluted and diverse expedition to the far north-western quarter between Cape Wrath and Ben Klibreck, an on-foot exploration of the mountains beyond Loch Shin. Remarkably, considering the ease with which we can now reach these once-remote places, he makes it sound like an epic trip to Arctic Norway. In those days, seven decades ago, it probably took as much planning.

‘A walking-cum-climbing holiday in north-west Sutherland is not planned overnight – at least not by those who wish to eat at fairly regular intervals,’ he wrote, before embarking on a description of what he called ‘the staff work’: the logistics, necessary permissions and the booking of the train journey from Glasgow to Crask, just north of Lairg.

Tom and his companions (he never mentioned their names or how many there were) travelled to Inverness and onwards by train, eventually to Lairg, ‘with long halts at each stop,’ before a local bus to Tongue dropped them off at the old inn at Crask. The weather was foul, but it didn’t deter them. They tackled Ben Klibreck ‘at a furious pace.’

Despite careful planning there is a gloriously haphazard feel to this early expedition, and much speculation about the possibilities of future trips, but no reference to guidebooks or ticking off Munros (Scottish mountains over 3,000 feet) or Corbetts (Scottish hills between 2,500 feet and 2,999 feet). This was unadulterated exploration: peeping around corners, gazing at far horizons, discovering raw adventure in an area of Scotland that, at the time, attracted few visitors. Tom once told me that he believed his generation ‘had the best of it’. It was an era when people still lived in remote glens, when exploration and discovery were genuine and not something you just googled on a computer.

‘I treasure memories of spending time with families like the Macraes of Carnmore in Letterewe or the Scotts at Luibeg in the Cairngorms. The glens are emptier now that they have gone. The hills weren’t so busy then and people weren’t rushing to climb Munros and Corbetts.’

It’s difficult to assess Tom Weir’s contribution to Scottish life and culture, simply because he was such a ‘lad o’many pairts’: writer, photographer, climber, explorer, ornithologist and television presenter. His influence on others was immense and he was always keen to share his vast knowledge of Scotland and of ornithology through his writings, his television programmes and innumerable slide shows. I’m certain his association with the Scots Magazine partly assured the title’s great longevity and popularity, and he outlasted several editors. Indeed, I’m told the online collection of his ‘My Month’ columns is still extremely popular, just as his television programmes, which for many years were broadcast during the wee, sma’ hours, eventually found new audiences among Scotland’s insomniac community. That would have made him smile.

Perhaps it’s best to leave the last word about Tommy to his great friend and colleague, W. H. Murray. Before submitting the manuscript of his autobiography Weir’s World to the publisher, Tom asked Bill Murray to read it and offer a criticism. This is what he said:

The general impression I have is one of amazement at all you have managed to pack into your life. In a book of life one can turn the pages, back as well as forward; the ingredients are so many, not set down in chronological order, that it’s like a well-stirred brew. I wish you all good fortune and sales.

The autobiography was published in 1994.

Tom passed away in a care home in Balloch on 6th July 2006. We’ll never see his likes again.

The pull of the mountains, and its rewards, is not something you can buy online or in a shop. You can’t ask someone to manufacture it for you. Mountains and wildness settle peace on the soul. It’s a wonderful phenomenon, and it doesn’t need any help. The sheer beauty of it, and our appreciation of that beauty, is partly because, as the Harvard author and naturalist Edward O. Wilson once said, ‘it’s beyond human contrivance.’

I consider myself very fortunate to live in Scotland. Here, lying on the edge of Europe, I’m proud to live in what is recognised as one of the most beautiful countries in the world. Small but perfectly formed, we can boast some of the finest, and most diverse, wild landscapes. Add to that the best access legislation in Europe and what you get is a paradise for hillwalkers and mountaineers. The weather isn’t perfect, I’ll give you that, and we often curse the Highland climate that sometimes feels like five months of winter and seven months’ bad weather, but that’s rarely the truth of it. The weather can be fickle but it’s those very meteorological complexities that create the moods and impressions – the atmospheres – that make hillwalking in Scotland so unique. Our mountains may not be high, but they are diverse, and there is fascination and wonder in that diversity. Try comparing the Cairngorms with the Cuillin, or the ancient rocks of Torridon with the rounded hills of the Borders, or the hills of the Trossachs with the individualistic monoliths of the far North-West Highlands.

There is a diversity in our culture too, and in our language and music, a richness that creates continued interest. Folklore and heritage are amongst my own passions and the hills and wild areas of Scotland have enriched that. These are not ‘empty lands’ as some proclaim or, as I saw it described recently on social media, a ‘blank canvas’, but areas that still exhibit the hand of man almost everywhere: traces of the ancient runrig systems of agriculture, the faint lines of the lazybeds on a hillside, historic stalkers’ paths and military roads, gables and drystone walls of old homes, and uninhabited villages still alive with whispers and memories.

I cycle most days, and climb hills as often as the body allows. I spend a lot of time exploring out-of-the-way corners of the Highlands and Islands, researching articles for the Scots Magazine and other titles. I still edit the quarterly magazines Scottish Walks and Scottish Cycling and take a lot of pleasure in producing a little series of videos that are broadcast on YouTube. Gina and I still chill out at folk festivals and the annual Celtic Connections festival in Glasgow. All these things and the elements that link them provide a fascinating and satisfying lifestyle, an existence that provides an outlet for that continual pull of the hills.

2

Ecology of the Imagination

Few countries in the world can boast the amazing diversity of landscape found in Scotland. Compare the windswept, rolling landscapes of Aberdeenshire, or Banff and Buchan, with the jagged upthrusts of Wester Ross. Or contrast the physical attributes of the mastiff-like Cairngorms with the serrated skyline of the Skye Cuillin, to appreciate that diversity. Running parallel is a multiplicity of culture. The good folk of Harris enjoy a culture, and a language, very different from the Doric of Banff and Buchan and I suspect such contrasts are why I love to visit the polar opposite of my own home area of the Cairngorms.

The Scottish Borders is as different as rugby is from shinty, but I feel comfortable there, a contentment largely due to a long-standing passion for traditional ballads, the reivers and the folklore and legends to be found amongst the cleughs and rolling hills. I’ve always felt very much at ease there, particularly in springtime.

When Gina and I ran the youth hostel in Aviemore in the late seventies, we always greeted the arrival of winter with a genuine welcome. Days of skiing and winter climbing lay ahead, and we embraced the cold and icy forecasts with the enthusiasm of innocent bairns, but by March that childlike enthusiasm had waned. We were tired of trudging through slushy snow and digging out the driveway every couple of days. By then winter had lost its appeal. Those were the days when the Scottish Highlands were almost guaranteed white winters, when the village of Aviemore thrived as a ski resort and it wasn’t unusual to have snow on the ground from November to March.

At that time I taught cross-country skiing and winter hillcraft courses in the Cairngorms and was climbing, hiking or skiing on snow most days, so by the end of February I was snow-stir-crazy and desperate to walk on green grass again, eager to smell the earth. To escape the monochrome landscapes we used to drive over to Skye where my pal Willie Wallace ran the Broadford Youth Hostel. Being close to the sea it was rare for Broadford to get any snow at all, so not only did we enjoy the social aspect of visiting Willie and his wife Judith but we also relished the milder temperatures, and seeing the land shake off the winter doldrums with signs of new life.

When Willie died and Judith moved away, we changed our late-winter holiday destination and drove to the Borders instead. With the Highland hills still streaked with snow it was a real joy to head south to where springtime was more advanced, daffodils swayed in yellow dance and newborn lambs gambolled on a green sheen of new growth. It was another world, and only a few hours from home, but there was another aspect of Border life that always attracted me. This is a land where an aura of mysticism pervades local culture, a land rich in legend and folklore. The author H. V. Morton described it well:

How can I describe the strange knowingness of the Border? Its uncanny watchfulness. Its queer trick of seeming still to listen and wait. I feel that invisible things are watching me. Out of the fern silently might ride the Queen of Elfland, just as she came to Thomas of Ercildoune in this very country with ‘fifty silver bells and nine’ hanging from her horse’s mane.

I believe these ancient and long-loved tales are more than faery stories, more than magical fables. They are what author and environmentalist Alastair McIntosh would call part of the ‘ecology of the imagination’: ‘Ecology emanates from the cosmic imagination. Imagination leads back to ecology.’

Could imagination be part of a greater realm that contains the wilder reaches of ecology and of poetry, or is it a quality that we only possess privately? I believe it may be both, and folklore may help us reconcile those things that live in our mind’s eye as well as events that may, or may not, have shaped history. There is nowhere else in Scotland that I sense this ‘uncanny watchfulness’ as intensely as I do here. It lurks on every hilltop, in every cleuch, and in every castle ruin.

For a few precious days each year we would head south to climb the snowless hills, ride our bikes and spend the nights in our campervan in some out-of-the-way places. On one occasion Gina adopted a donkey at the Scottish Borders Donkey Sanctuary so we took the opportunity to visit him with a gift of carrots. He returned the favour by biting her on the arm, giving some credence to Robert Louis Stevenson’s assertion that donkeys were pretty untrustworthy creatures. We often stay near Peebles, ‘the comfortable, sonsy and still good-looking matron of the Borderland,’ to quote novelist and historian Nigel Tranter, and cycle some of the easier routes at Glentress Mountain Bike Centre, a place buzzing with technicolour lycra and expensive-looking bikes. If Peebles is the sonsy matron of the Borders then Melrose surely has to be the posh, well-to-do aunt.

Melrose has been described as ‘the only upper-middle-class town in the Scottish Borders.’ It certainly has a Cotswold middle-class feel to it but at the same time is undeniably Scottish. Despite its county-town feel, the appeal is enduring. The Romans settled here, establishing the supply camp of Trimontium, and one of sports longest-lasting events was devised here in 1877. The Melrose Sevens, one of rugby’s most popular events, attracts the television cameras and about 16,000 visitors every year, filling the pubs and hotels to bursting; but Melrose’s most popular attraction is undoubtedly the Abbey.

Founded in 1136 by Cistercian monks from Rievaulx in Yorkshire, Melrose Abbey is today the starting point of the popular sixty-four-mile St Cuthbert’s Way, which crosses the Borderlands on its way to Holy Island. St Cuthbert was part of the abbey community before he moved to the island of Lindisfarne, just off the Northumberland coast, and to eternal glory at Durham, as one of the north’s best-loved saints. The abbey is also the resting place of Robert the Bruce’s heart after it had been taken as a talisman by Scots crusaders, and author Dan Brown may have found some interesting material here for his novels on religious cults and Freemasonry. The masons who worked on the abbey have been linked to the Freemasons’ Lodge of Melrose – St John No 1. Here you’ll find a plaque bearing the masons’ coat of arms. The date on it is 1156.

It’s said that Michael Scott the Wizard (what kind of name is that for a wizard? Merlin or Gandalf or even Lord Voldemort, but Michael Scott?) is also buried in the grounds of the Abbey, along with his magic books. He is said to have predicted his own death by a small stone falling on his head. Despite his un-wizardlike name, Michael Scott became a legend and there is little doubt that he did exist. According to many written accounts he was a thirteenth-century philosopher who studied at Oxford, Paris and Toledo universities, and became known as Michael Mathematicus.

It’s believed he was court astrologer and physician to Frederick the Second, the Holy Roman Emperor known as Frederick the Great. Sir Walter Scott mentioned him in his Lay of the Last Minstrel and James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd, wrote about him in his book, The Three Perils of Man. The Scottish novelist John Buchan also referred to him in his 1924 book The Three Hostages, but Michael Scott the Wizard may have another claim to fame, one more important than philosophy, mathematics or magic. It has been suggested that he is the father of Scotch whisky.

Surviving copies of manuscripts attributed to Scott refer to distillation of aqua vitae (water of life), sometimes known as aqua ardens (burning water), the earliest name for distilled alcohol. In the Middle Ages people distilled spirits and used them to cure their ills, much as we do today, but I really like the reference to whisky by another Borderer, James Hogg. The Ettrick Shepherd wrote, ‘If a body can just find oot the exac’ proper proportion and quantity that ought to be drunk every day and keep to that, I verily throw that he might leeve forever without dying at all, and that doctors and kirkyards would go oot o’ fashion’. I can certainly drink to that.

Towns are certainly nice for a quick dram or two, a meal or a good cup of coffee, but before arriving in Melrose we often enjoyed the view from lowly Bemersyde Hill. Like Sir Walter Scott, we would gaze across the winding River Tweed to admire one of the great landmarks of the Borders: the Eildons. A round of those landmark hills would once again be one of our weekend walks. I’m not sure how many times I’ve climbed the Eildons but I never tire of them. I’ve written about them, made television programmes on them, I included them in my long walk between Kirk Yetholm and Cape Wrath, the Scottish National Trail, and I’m always keen to climb them again.

When Sir Walter Scott saw the Eildons across the Tweed from Bemersyde Hill he claimed it as one of the best views in the Borders. Little did he know that he was gazing at the remnants of a volcanic lava flow that time, wind, rain and ice had weathered into a distinct triumvirate of dumpy hills. They were known to the Romans as Trimontium.

I suspect there is one thing that Sir Walter Scott and I have in common. We are both romantics and, like the famed novelist, I prefer the less prosaic and infinitely more romantic reasoning for the creation of the lovely Eildons. The local tradition casts aside geological hypotheses and meteorological theories to make a simple claim. Michael Scott the Wizard was ordered by the devil to split a single Eildon into three separate humps.

If you find that difficult to swallow then consider the fate of another local hero, the songster called Thomas the Rhymer. Thomas was a thirteenth-century bard and seer who claimed to have been spirited away by the Queen of the Faeries to spend seven years in Elfland, below the Eildon Hills. As if that’s not enough, Borders lore has it that Merlin, the great wizard at the court of King Arthur, was stoned to death and buried at nearby Drumelzier on the banks of the Tweed. This area of the Borders wears its history like an ornate ball gown. It dazzles and intrigues you.

I admit I’m a sucker for tales like these, especially when wrapped in the verses of a Border ballad. Arriving in Melrose we noticed an advert for an evening of traditional songs in one of the hotels, so once we had eaten we spent the rest of the evening with pints of beer, guitars, fiddles and small pipes and some great singing. It was magic, but not as magical as climbing the Eildons’ North Hill next morning: the site of an ancient city, the home of the ancient Selgovae tribe. Archaeologists suggest there could have been over 300 hut circles here around 2,000 years ago. Later, the Romans used the site as a fort and signal station.