3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ALEMAR S.A.S.

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

- This edition is unique;

- The translation is completely original and was carried out for the Ale. Mar. SAS;

- All rights reserved.

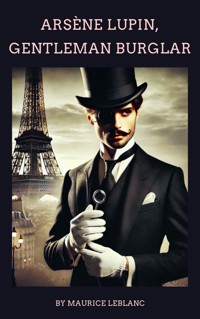

Arsène Lupin, Gentleman Burglar is the first collection of stories by Maurice Leblanc, featuring the gentleman thief and master of disguise, Arsène Lupin. The book contains nine short stories including: The Arrest of Arsène Lupin (in which Lupin boards a ship in order to steal from the passengers); Arsène Lupin in Prison (in which Lupin sends a letter to a Baron, telling him to send his valuables or he will steal them); The Escape of Arsène Lupin (in which Lupin outsmarts officials who believe he is planning an escape from prison); The Mysterious Traveller; The Queen’s Necklace; The Seven of Hearts; Madame Imbert’s Safe; The Black Pearl; and, Sherlock Holmes Arrives Too Late. The mention of Sherlock Holmes was changed to 'Herlock Sholmes' in subsequent publications after legal objections from Arthur Conan Doyle.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

1. The Arrest of Arsène Lupin

2. Arsène Lupin In Prison

3. The Escape of Arsène Lupin

4. The Mysterious Traveller

5. The Queen’s Necklace

6. The Seven of Hearts

7. Madame Imbert’s Safe

8. The Black Pearl

9. Sherlock Holmes Arrives Too Late

Arsène Lupin, Gentleman BurglarMaurice Leblanc

1. The Arrest of Arsène Lupin

It was a strange ending to a voyage that had commenced in a most auspicious manner. The transatlantic steamship ‘La Provence’ was a swift and comfortable vessel, under the command of a most affable man. The passengers constituted a select and delightful society. The charm of new acquaintances and improvised amusements served to make the time pass agreeably. We enjoyed the pleasant sensation of being separated from the world, living, as it were, upon an unknown island, and consequently obliged to be sociable with each other.

Have you ever stopped to consider how much originality and spontaneity emanate from these various individuals who, on the preceding evening, did not even know each other, and who are now, for several days, condemned to lead a life of extreme intimacy, jointly defying the anger of the ocean, the terrible onslaught of the waves, the violence of the tempest and the agonizing monotony of the calm and sleepy water? Such a life becomes a sort of tragic existence, with its storms and its grandeurs, its monotony and its diversity; and that is why, perhaps, we embark upon that short voyage with mingled feelings of pleasure and fear.

But, during the past few years, a new sensation had been added to the life of the transatlantic traveler. The little floating island is now attached to the world from which it was once quite free. A bond united them, even in the very heart of the watery wastes of the Atlantic. That bond is the wireless telegraph, by means of which we receive news in the most mysterious manner. We know full well that the message is not transported by the medium of a hollow wire. No, the mystery is even more inexplicable, more romantic, and we must have recourse to the wings of the air in order to explain this new miracle. During the first day of the voyage, we felt that we were being followed, escorted, preceded even, by that distant voice, which, from time to time, whispered to one of us a few words from the receding world. Two friends spoke to me. Ten, twenty others sent gay or somber words of parting to other passengers.

On the second day, at a distance of five hundred miles from the French coast, in the midst of a violent storm, we received the following message by means of the wireless telegraph:

“Arsène Lupin is on your vessel, first cabin, blonde hair, wound right fore-arm, traveling alone under name of R........”

At that moment, a terrible flash of lightning rent the stormy skies. The electric waves were interrupted. The remainder of the dispatch never reached us. Of the name under which Arsène Lupin was concealing himself, we knew only the initial.

If the news had been of some other character, I have no doubt that the secret would have been carefully guarded by the telegraphic operator as well as by the officers of the vessel. But it was one of those events calculated to escape from the most rigorous discretion. The same day, no one knew how, the incident became a matter of current gossip and every passenger was aware that the famous Arsène Lupin was hiding in our midst.

Arsène Lupin in our midst! the irresponsible burglar whose exploits had been narrated in all the newspapers during the past few months! the mysterious individual with whom Ganimard, our shrewdest detective, had been engaged in an implacable conflict amidst interesting and picturesque surroundings. Arsène Lupin, the eccentric gentleman who operates only in the chateaux and salons, and who, one night, entered the residence of Baron Schormann, but emerged empty-handed, leaving, however, his card on which he had scribbled these words: “Arsène Lupin, gentleman-burglar, will return when the furniture is genuine.” Arsène Lupin, the man of a thousand disguises: in turn a chauffer, detective, bookmaker, Russian physician, Spanish bull-fighter, commercial traveler, robust youth, or decrepit old man.

Then consider this startling situation: Arsène Lupin was wandering about within the limited bounds of a transatlantic steamer; in that very small corner of the world, in that dining saloon, in that smoking room, in that music room! Arsène Lupin was, perhaps, this gentleman.... or that one.... my neighbor at the table.... the sharer of my stateroom....

“And this condition of affairs will last for five days!” exclaimed Miss Nelly Underdown, next morning. “It is unbearable! I hope he will be arrested.”

Then, addressing me, she added:

“And you, Monsieur d’Andrézy, you are on intimate terms with the captain; surely you know something?”

I should have been delighted had I possessed any information that would interest Miss Nelly. She was one of those magnificent creatures who inevitably attract attention in every assembly. Wealth and beauty form an irresistible combination, and Nelly possessed both.

Educated in Paris under the care of a French mother, she was now going to visit her father, the millionaire Underdown of Chicago. She was accompanied by one of her friends, Lady Jerland.

At first, I had decided to open a flirtation with her; but, in the rapidly growing intimacy of the voyage, I was soon impressed by her charming manner and my feelings became too deep and reverential for a mere flirtation. Moreover, she accepted my attentions with a certain degree of favor. She condescended to laugh at my witticisms and display an interest in my stories. Yet I felt that I had a rival in the person of a young man with quiet and refined tastes; and it struck me, at times, that she preferred his taciturn humor to my Parisian frivolity. He formed one in the circle of admirers that surrounded Miss Nelly at the time she addressed to me the foregoing question. We were all comfortably seated in our deck-chairs. The storm of the preceding evening had cleared the sky. The weather was now delightful.

“I have no definite knowledge, mademoiselle,” I replied, “but can not we, ourselves, investigate the mystery quite as well as the detective Ganimard, the personal enemy of Arsène Lupin?”

“Oh! oh! you are progressing very fast, monsieur.”

“Not at all, mademoiselle. In the first place, let me ask, do you find the problem a complicated one?”

“Very complicated.”

“Have you forgotten the key we hold for the solution to the problem?”

“What key?”

“In the first place, Lupin calls himself Monsieur R———-.”

“Rather vague information,” she replied.

“Secondly, he is traveling alone.”

“Does that help you?” she asked.

“Thirdly, he is blonde.”

“Well?”

“Then we have only to peruse the passenger-list, and proceed by process of elimination.”

I had that list in my pocket. I took it out and glanced through it. Then I remarked:

“I find that there are only thirteen men on the passenger-list whose names begin with the letter R.”

“Only thirteen?”

“Yes, in the first cabin. And of those thirteen, I find that nine of them are accompanied by women, children or servants. That leaves only four who are traveling alone. First, the Marquis de Raverdan——”

“Secretary to the American Ambassador,” interrupted Miss Nelly. “I know him.”

“Major Rawson,” I continued.

“He is my uncle,” some one said.

“Mon. Rivolta.”

“Here!” exclaimed an Italian, whose face was concealed beneath a heavy black beard.

Miss Nelly burst into laughter, and exclaimed: “That gentleman can scarcely be called a blonde.”

“Very well, then,” I said, “we are forced to the conclusion that the guilty party is the last one on the list.”

“What is his name?”

“Mon. Rozaine. Does anyone know him?”

No one answered. But Miss Nelly turned to the taciturn young man, whose attentions to her had annoyed me, and said:

“Well, Monsieur Rozaine, why do you not answer?”

All eyes were now turned upon him. He was a blonde. I must confess that I myself felt a shock of surprise, and the profound silence that followed her question indicated that the others present also viewed the situation with a feeling of sudden alarm. However, the idea was an absurd one, because the gentleman in question presented an air of the most perfect innocence.

“Why do I not answer?” he said. “Because, considering my name, my position as a solitary traveler and the color of my hair, I have already reached the same conclusion, and now think that I should be arrested.”

He presented a strange appearance as he uttered these words. His thin lips were drawn closer than usual and his face was ghastly pale, whilst his eyes were streaked with blood. Of course, he was joking, yet his appearance and attitude impressed us strangely.

“But you have not the wound?” said Miss Nelly, naively.

“That is true,” he replied, “I lack the wound.”

Then he pulled up his sleeve, removing his cuff, and showed us his arm. But that action did not deceive me. He had shown us his left arm, and I was on the point of calling his attention to the fact, when another incident diverted our attention. Lady Jerland, Miss Nelly’s friend, came running towards us in a state of great excitement, exclaiming:

“My jewels, my pearls! Some one has stolen them all!”

No, they were not all gone, as we soon found out. The thief had taken only part of them; a very curious thing. Of the diamond sunbursts, jeweled pendants, bracelets and necklaces, the thief had taken, not the largest but the finest and most valuable stones. The mountings were lying upon the table. I saw them there, despoiled of their jewels, like flowers from which the beautiful colored petals had been ruthlessly plucked. And this theft must have been committed at the time Lady Jerland was taking her tea; in broad daylight, in a stateroom opening on a much frequented corridor; moreover, the thief had been obliged to force open the door of the stateroom, search for the jewel-case, which was hidden at the bottom of a hat-box, open it, select his booty and remove it from the mountings.

Of course, all the passengers instantly reached the same conclusion; it was the work of Arsène Lupin.

That day, at the dinner table, the seats to the right and left of Rozaine remained vacant; and, during the evening, it was rumored that the captain had placed him under arrest, which information produced a feeling of safety and relief. We breathed once more. That evening, we resumed our games and dances. Miss Nelly, especially, displayed a spirit of thoughtless gayety which convinced me that if Rozaine’s attentions had been agreeable to her in the beginning, she had already forgotten them. Her charm and good-humor completed my conquest. At midnight, under a bright moon, I declared my devotion with an ardor that did not seem to displease her.

But, next day, to our general amazement, Rozaine was at liberty. We learned that the evidence against him was not sufficient. He had produced documents that were perfectly regular, which showed that he was the son of a wealthy merchant of Bordeaux. Besides, his arms did not bear the slightest trace of a wound.

“Documents! Certificates of birth!” exclaimed the enemies of Rozaine, “of course, Arsène Lupin will furnish you as many as you desire. And as to the wound, he never had it, or he has removed it.”

Then it was proven that, at the time of the theft, Rozaine was promenading on the deck. To which fact, his enemies replied that a man like Arsène Lupin could commit a crime without being actually present. And then, apart from all other circumstances, there remained one point which even the most skeptical could not answer: Who except Rozaine, was traveling alone, was a blonde, and bore a name beginning with R? To whom did the telegram point, if it were not Rozaine?

And when Rozaine, a few minutes before breakfast, came boldly toward our group, Miss Nelly and Lady Jerland arose and walked away.

An hour later, a manuscript circular was passed from hand to hand amongst the sailors, the stewards, and the passengers of all classes. It announced that Mon. Louis Rozaine offered a reward of ten thousand francs for the discovery of Arsène Lupin or other person in possession of the stolen jewels.

“And if no one assists me, I will unmask the scoundrel myself,” declared Rozaine.

Rozaine against Arsène Lupin, or rather, according to current opinion, Arsène Lupin himself against Arsène Lupin; the contest promised to be interesting.

Nothing developed during the next two days. We saw Rozaine wandering about, day and night, searching, questioning, investigating. The captain, also, displayed commendable activity. He caused the vessel to be searched from stern to stern; ransacked every stateroom under the plausible theory that the jewels might be concealed anywhere, except in the thief’s own room.

“I suppose they will find out something soon,” remarked Miss Nelly to me. “He may be a wizard, but he cannot make diamonds and pearls become invisible.”

“Certainly not,” I replied, “but he should examine the lining of our hats and vests and everything we carry with us.”

Then, exhibiting my Kodak, a 9x12 with which I had been photographing her in various poses, I added: “In an apparatus no larger than that, a person could hide all of Lady Jerland’s jewels. He could pretend to take pictures and no one would suspect the game.”

“But I have heard it said that every thief leaves some clue behind him.”

“That may be generally true,” I replied, “but there is one exception: Arsène Lupin.”

“Why?”

“Because he concentrates his thoughts not only on the theft, but on all the circumstances connected with it that could serve as a clue to his identity.”

“A few days ago, you were more confident.”

“Yes, but since I have seen him at work.”

“And what do you think about it now?” she asked.

“Well, in my opinion, we are wasting our time.”

And, as a matter of fact, the investigation had produced no result. But, in the meantime, the captain’s watch had been stolen. He was furious. He quickened his efforts and watched Rozaine more closely than before. But, on the following day, the watch was found in the second officer’s collar box.

This incident caused considerable astonishment, and displayed the humorous side of Arsène Lupin, burglar though he was, but dilettante as well. He combined business with pleasure. He reminded us of the author who almost died in a fit of laughter provoked by his own play. Certainly, he was an artist in his particular line of work, and whenever I saw Rozaine, gloomy and reserved, and thought of the double role that he was playing, I accorded him a certain measure of admiration.

On the following evening, the officer on deck duty heard groans emanating from the darkest corner of the ship. He approached and found a man lying there, his head enveloped in a thick gray scarf and his hands tied together with a heavy cord. It was Rozaine. He had been assaulted, thrown down and robbed. A card, pinned to his coat, bore these words: “Arsène Lupin accepts with pleasure the ten thousand francs offered by Mon. Rozaine.” As a matter of fact, the stolen pocket-book contained twenty thousand francs.

Of course, some accused the unfortunate man of having simulated this attack on himself. But, apart from the fact that he could not have bound himself in that manner, it was established that the writing on the card was entirely different from that of Rozaine, but, on the contrary, resembled the handwriting of Arsène Lupin as it was reproduced in an old newspaper found on board.

Thus it appeared that Rozaine was not Arsène Lupin; but was Rozaine, the son of a Bordeaux merchant. And the presence of Arsène Lupin was once more affirmed, and that in a most alarming manner.

Such was the state of terror amongst the passengers that none would remain alone in a stateroom or wander singly in unfrequented parts of the vessel. We clung together as a matter of safety. And yet the most intimate acquaintances were estranged by a mutual feeling of distrust. Arsène Lupin was, now, anybody and everybody. Our excited imaginations attributed to him miraculous and unlimited power. We supposed him capable of assuming the most unexpected disguises; of being, by turns, the highly respectable Major Rawson or the noble Marquis de Raverdan, or even—for we no longer stopped with the accusing letter of R—or even such or such a person well known to all of us, and having wife, children and servants.

The first wireless dispatches from America brought no news; at least, the captain did not communicate any to us. The silence was not reassuring.

Our last day on the steamer seemed interminable. We lived in constant fear of some disaster. This time, it would not be a simple theft or a comparatively harmless assault; it would be a crime, a murder. No one imagined that Arsène Lupin would confine himself to those two trifling offenses. Absolute master of the ship, the authorities powerless, he could do whatever he pleased; our property and lives were at his mercy.

Yet those were delightful hours for me, since they secured to me the confidence of Miss Nelly. Deeply moved by those startling events and being of a highly nervous nature, she spontaneously sought at my side a protection and security that I was pleased to give her. Inwardly, I blessed Arsène Lupin. Had he not been the means of bringing me and Miss Nelly closer to each other? Thanks to him, I could now indulge in delicious dreams of love and happiness—dreams that, I felt, were not unwelcome to Miss Nelly. Her smiling eyes authorized me to make them; the softness of her voice bade me hope.

As we approached the American shore, the active search for the thief was apparently abandoned, and we were anxiously awaiting the supreme moment in which the mysterious enigma would be explained. Who was Arsène Lupin? Under what name, under what disguise was the famous Arsène Lupin concealing himself? And, at last, that supreme moment arrived. If I live one hundred years, I shall not forget the slightest details of it.

“How pale you are, Miss Nelly,” I said to my companion, as she leaned upon my arm, almost fainting.

“And you!” she replied, “ah! you are so changed.”

“Just think! this is a most exciting moment, and I am delighted to spend it with you, Miss Nelly. I hope that your memory will sometimes revert—-”

But she was not listening. She was nervous and excited. The gangway was placed in position, but, before we could use it, the uniformed customs officers came on board. Miss Nelly murmured:

“I shouldn’t be surprised to hear that Arsène Lupin escaped from the vessel during the voyage.”

“Perhaps he preferred death to dishonor, and plunged into the Atlantic rather than be arrested.”

“Oh, do not laugh,” she said.

Suddenly I started, and, in answer to her question, I said:

“Do you see that little old man standing at the bottom of the gangway?”

“With an umbrella and an olive-green coat?”

“It is Ganimard.”

“Ganimard?”

“Yes, the celebrated detective who has sworn to capture Arsène Lupin. Ah! I can understand now why we did not receive any news from this side of the Atlantic. Ganimard was here! and he always keeps his business secret.”

“Then you think he will arrest Arsène Lupin?”

“Who can tell? The unexpected always happens when Arsène Lupin is concerned in the affair.”

“Oh!” she exclaimed, with that morbid curiosity peculiar to women, “I should like to see him arrested.”

“You will have to be patient. No doubt, Arsène Lupin has already seen his enemy and will not be in a hurry to leave the steamer.”

The passengers were now leaving the steamer. Leaning on his umbrella, with an air of careless indifference, Ganimard appeared to be paying no attention to the crowd that was hurrying down the gangway. The Marquis de Raverdan, Major Rawson, the Italian Rivolta, and many others had already left the vessel before Rozaine appeared. Poor Rozaine!

“Perhaps it is he, after all,” said Miss Nelly to me. “What do you think?”

“I think it would be very interesting to have Ganimard and Rozaine in the same picture. You take the camera. I am loaded down.”

I gave her the camera, but too late for her to use it. Rozaine was already passing the detective. An American officer, standing behind Ganimard, leaned forward and whispered in his ear. The French detective shrugged his shoulders and Rozaine passed on. Then, my God, who was Arsène Lupin?

“Yes,” said Miss Nelly, aloud, “who can it be?”

Not more than twenty people now remained on board. She scrutinized them one by one, fearful that Arsène Lupin was not amongst them.

“We cannot wait much longer,” I said to her.

She started toward the gangway. I followed. But we had not taken ten steps when Ganimard barred our passage.

“Well, what is it?” I exclaimed.

“One moment, monsieur. What’s your hurry?”

“I am escorting mademoiselle.”

“One moment,” he repeated, in a tone of authority. Then, gazing into my eyes, he said:

“Arsène Lupin, is it not?”

I laughed, and replied: “No, simply Bernard d’Andrézy.”

“Bernard d’Andrézy died in Macedonia three years ago.”

“If Bernard d’Andrézy were dead, I should not be here. But you are mistaken. Here are my papers.”

“They are his; and I can tell you exactly how they came into your possession.”

“You are a fool!” I exclaimed. “Arsène Lupin sailed under the name of R—-”

“Yes, another of your tricks; a false scent that deceived them at Havre. You play a good game, my boy, but this time luck is against you.”

I hesitated a moment. Then he hit me a sharp blow on the right arm, which caused me to utter a cry of pain. He had struck the wound, yet unhealed, referred to in the telegram.

I was obliged to surrender. There was no alternative. I turned to Miss Nelly, who had heard everything. Our eyes met; then she glanced at the Kodak I had placed in her hands, and made a gesture that conveyed to me the impression that she understood everything. Yes, there, between the narrow folds of black leather, in the hollow centre of the small object that I had taken the precaution to place in her hands before Ganimard arrested me, it was there I had deposited Rozaine’s twenty thousand francs and Lady Jerland’s pearls and diamonds.

Oh! I pledge my oath that, at that solemn moment, when I was in the grasp of Ganimard and his two assistants, I was perfectly indifferent to everything, to my arrest, the hostility of the people, everything except this one question: what will Miss Nelly do with the things I had confided to her?

In the absence of that material and conclusive proof, I had nothing to fear; but would Miss Nelly decide to furnish that proof? Would she betray me? Would she act the part of an enemy who cannot forgive, or that of a woman whose scorn is softened by feelings of indulgence and involuntary sympathy?

She passed in front of me. I said nothing, but bowed very low. Mingled with the other passengers, she advanced to the gangway with my Kodak in her hand. It occurred to me that she would not dare to expose me publicly, but she might do so when she reached a more private place. However, when she had passed only a few feet down the gangway, with a movement of simulated awkwardness, she let the camera fall into the water between the vessel and the pier. Then she walked down the gangway, and was quickly lost to sight in the crowd. She had passed out of my life forever.

For a moment, I stood motionless. Then, to Ganimard’s great astonishment, I muttered:

“What a pity that I am not an honest man!”

Such was the story of his arrest as narrated to me by Arsène Lupin himself. The various incidents, which I shall record in writing at a later day, have established between us certain ties.... shall I say of friendship? Yes, I venture to believe that Arsène Lupin honors me with his friendship, and that it is through friendship that he occasionally calls on me, and brings, into the silence of my library, his youthful exuberance of spirits, the contagion of his enthusiasm, and the mirth of a man for whom destiny has naught but favors and smiles.

His portrait? How can I describe him? I have seen him twenty times and each time he was a different person; even he himself said to me on one occasion: “I no longer know who I am. I cannot recognize myself in the mirror.” Certainly, he was a great actor, and possessed a marvelous faculty for disguising himself. Without the slightest effort, he could adopt the voice, gestures and mannerisms of another person.

“Why,” said he, “why should I retain a definite form and feature? Why not avoid the danger of a personality that is ever the same? My actions will serve to identify me.”

Then he added, with a touch of pride:

“So much the better if no one can ever say with absolute certainty: There is Arsène Lupin! The essential point is that the public may be able to refer to my work and say, without fear of mistake: Arsène Lupin did that!”

2. Arsène Lupin In Prison

There is no tourist worthy of the name who does not know the banks of the Seine, and has not noticed, in passing, the little feudal castle of the Malaquis, built upon a rock in the centre of the river. An arched bridge connects it with the shore. All around it, the calm waters of the great river play peacefully amongst the reeds, and the wagtails flutter over the moist crests of the stones.

The history of the Malaquis castle is stormy like its name, harsh like its outlines. It has passed through a long series of combats, sieges, assaults, rapines and massacres. A recital of the crimes that have been committed there would cause the stoutest heart to tremble. There are many mysterious legends connected with the castle, and they tell us of a famous subterranean tunnel that formerly led to the abbey of Jumieges and to the manor of Agnes Sorel, mistress of Charles VII.

In that ancient habitation of heroes and brigands, the Baron Nathan Cahorn now lived; or Baron Satan as he was formerly called on the Bourse, where he had acquired a fortune with incredible rapidity. The lords of Malaquis, absolutely ruined, had been obliged to sell the ancient castle at a great sacrifice. It contained an admirable collection of furniture, pictures, wood carvings, and faience. The Baron lived there alone, attended by three old servants. No one ever enters the place. No one had ever beheld the three Rubens that he possessed, his two Watteau, his Jean Goujon pulpit, and the many other treasures that he had acquired by a vast expenditure of money at public sales.

Baron Satan lived in constant fear, not for himself, but for the treasures that he had accumulated with such an earnest devotion and with so much perspicacity that the shrewdest merchant could not say that the Baron had ever erred in his taste or judgment. He loved them—his bibelots. He loved them intensely, like a miser; jealously, like a lover. Every day, at sunset, the iron gates at either end of the bridge and at the entrance to the court of honor are closed and barred. At the least touch on these gates, electric bells will ring throughout the castle.

One Thursday in September, a letter-carrier presented himself at the gate at the head of the bridge, and, as usual, it was the Baron himself who partially opened the heavy portal. He scrutinized the man as minutely as if he were a stranger, although the honest face and twinkling eyes of the postman had been familiar to the Baron for many years. The man laughed, as he said:

“It is only I, Monsieur le Baron. It is not another man wearing my cap and blouse.”

“One can never tell,” muttered the Baron.

The man handed him a number of newspapers, and then said:

“And now, Monsieur le Baron, here is something new.”

“Something new?”

“Yes, a letter. A registered letter.”

Living as a recluse, without friends or business relations, the baron never received any letters, and the one now presented to him immediately aroused within him a feeling of suspicion and distrust. It was like an evil omen. Who was this mysterious correspondent that dared to disturb the tranquility of his retreat?

“You must sign for it, Monsieur le Baron.”