Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

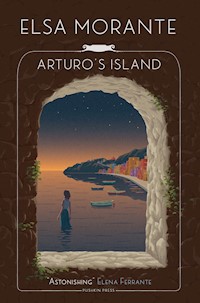

A moving Italian coming-of-age classic in a new translation by Ann Goldstein, celebrated translator of Elena Ferrante On a remote island in the Bay of Naples, a young boy roams the shore with only his dog for company. Arturo's mother died in childbirth and his wayward father Wilhelm rarely returns to the island. Left in isolation, he dreams up a world of romantic exploits in which his father sails the seas like the heroes in his favourite stories. When Wilhelm suddenly reappears with his new young wife Nunziata, Arturo's imagined world bursts apart, and he falls in passionate, tormented love. As Wilhelm's behaviour grows increasingly erratic, Arturo must begin to face the reality of his father's life, and of his own feelings. A deeply affecting tale of childhood disenchantment, Arturo's Island is a work of stunning emotional force by one of modern Italian literature's foremost writers. A new translation by Ann Goldstein. Elsa Morante (1912-1985) was an Italian novelist, short-story writer and poet. Born and raised in Rome, she started writing at a young age, initially publishing short stories in children's journals. Her first novel, House of Liars, was published in 1948 and won the Viareggio Prize. She went on to become one of Italy's most lauded writers, winning further prizes and commercial success with her next two novels, Arturo's Island (1957) and History (1974). She died of a heart attack in Rome in 1985.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 647

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

for Remo N.

What you thought was a tiny point on earth

was all.

And no one can ever steal that matchless treasure from your

jealous sleeping eyes.

Your first love will never be violated.

Virgin, she is wrapped in night

like a gypsy in her black shawl,

star suspended in the northern sky

for eternity: no danger can touch her.

Young friends, handsomer than Alexander and Euryalos,

forever handsome, protect the sleep of my boy.

The fearful emblem will never cross the threshold

of that blessed little island.

And you’ll never know the law

that I, like so many, have learned—

and that has broken my heart:

Outside Limbo there is no Elysium.

If I see myself in him, it seems clear to me …

— Umberto Saba, Il Canzoniere

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

King and Star of the Sky

… Paradise lofty and chaotic …

— SANDRO PENNA, POESIE

King and Star of the Sky

One of my first glories was my name. I had learned early (he, it seems to me, was the first to inform me) that Arturo—Arcturus—is a star: the swiftest and brightest light in the constellation of Boötes, the Herdsman, in the northern sky! And that this name was also borne by a king in ancient times, the commander of a band of faithful followers: all heroes, like the king himself, and treated by the king as equals, as brothers.

Unfortunately, I later discovered that that famous Arthur, King of Britain, was not a true story, only a legend; and so I abandoned him for other, more historical kings (in my opinion legends were childish). Still, another reason was enough in itself for me to give a noble value to the name Arturo: and that is, that it was my mother, I learned, who, although I think ignorant of the aristocratic symbolism, decided on that name. Who was herself simply an illiterate young woman but for me more than a sovereign.

In reality, I knew almost nothing about her, for she wasn’t even eighteen when she died, at the moment that I, her only child, was born. And the sole image of her I ever knew was a portrait on a postcard. A faded, ordinary, almost ghostlike figure, but the object of fantastic adoration for my entire childhood.

The poor itinerant photographer to whom we owe this unique image portrayed her in the first months of her pregnancy. You can tell from her body, even amid the folds of the loose-fitting dress, that she’s pregnant; and she holds her little hands clasped in front of her, as if to hide herself, in a timid, modest pose. She’s very serious, and in her black eyes you can read not only submissiveness, which is usual in most of our girls and young village brides, but a stunned and slightly fearful questioning. As if, among the common illusions of maternity, she already suspected that her destiny would be death and eternal ignorance.

The Island

All the islands of our archipelago, here in the Bay of Naples, are beautiful.

For the most part, the land is of volcanic origin, and, especially near the ancient craters, thousands of flowers grow wild: I’ve never seen anything like it on the mainland. In spring, the hills are covered with broom: traveling on the sea in the month of June you recognize its wild, caressing odor as soon as you approach our harbors.

Up in the hills in the countryside, my island has solitary narrow roads enclosed between ancient walls, behind which orchards and vineyards extend, like imperial gardens. It has several beaches with pale, fine sand, and other, smaller shores, covered with pebbles and shells, hidden amid high cliffs. In those towering rocks, which loom over the water, seagulls and turtledoves make their nests, and you can hear their voices, especially in the early morning, sometimes lamenting, sometimes gay. There, on quiet days, the sea is gentle and cool, and lies on the shore like dew. Ah, I wouldn’t ask to be a seagull or a dolphin; I’d be content to be a scorpion fish, the ugliest fish in the sea, just to be down there, playing in that water.

Around the port, the streets are all sunless alleys, lined with plain, centuries-old houses, which, although painted in beautiful pink or grayish shell colors, look severe and melancholy. On the sills of the small windows, which are almost as narrow as loopholes, you sometimes see a carnation growing in a tin can, or a little cage that seems fit for a cricket but holds a captured turtledove. The shops are as deep and dark as brigands’ dens. In the café at the port, there’s a coal stove on which the owner boils Turkish coffee, in a deep blue enameled coffeepot. She’s been a widow for many years, and always wears the black of mourning, the black shawl, the black earrings. A photograph of the deceased, on the wall beside the cash register, is festooned with dusty leaves.

The innkeeper, in his tavern, which is opposite the monument of Christ the Fisherman, is raising an owl, chained to a plank high up against the wall. The owl has delicate black and gray feathers, an elegant tuft on his head, blue eyelids, and big eyes of a red-gold color, circled with black; he always has a bleeding wing, because he constantly pecks at it with his beak. If you stretch out a hand to give him a little tickle on the chest, he bends his small head toward you, with an expression of wonder.

When evening descends, he starts to struggle, tries to take off, and falls back, and sometimes ends up hanging head down, flapping on his chain.

In the church at the port, the oldest on the island, there are some wax saints, less than three palms high, locked in glass cases. They have skirts of real lace, yellowed, faded cloaks of brocatelle, real hair, and from their wrists hang tiny rosaries of real pearls. On their small fingers, which have a deathly pallor, the nails are sketched with a threadlike red line.

Those elegant pleasure boats and cruise ships that in greater and greater numbers crowd the other ports of the archipelago hardly ever dock at ours; here you’ll see some barges or merchant ships, besides the fishing boats of the islanders. For many hours of the day the square at the port seems almost deserted; on the left, near the statue of Christ the Fisherman, a single carriage for hire awaits the arrival of the regularly scheduled steamers, which stop here for a few minutes and disembark three or four passengers altogether, mostly people from the island. Never, not even in summer, do our solitary beaches experience the commotion of the bathers from Naples and other cities, and all parts of the world, who throng the beaches of the surrounding areas. And if a stranger happens to get off at Procida, he marvels at not finding here that open and happy life, of celebrations and conversations on the street, of song and the strains of guitars or mandolins, for which the region of Naples is known throughout the world. The Procidans are surly, taciturn. All the doors are closed, almost no one looks out the window, every family lives within its four walls and doesn’t mingle with the others. Friendship, among us, isn’t welcomed. And the arrival of a stranger arouses not curiosity but, rather, distrust. If he asks questions, they are answered reluctantly, because the people of my island don’t like their privacy spied on.

They are a small dark race, with elongated black eyes, like Orientals. And they so closely resemble one another you might say they’re all related. The women, following ancient custom, live cloistered like nuns. Many of them still wear their hair coiled, shawls over their heads, long dresses, and, in winter, clogs over thick black cotton stockings; in summer some go barefoot. When they pass barefoot, rapid and noiseless, avoiding encounters, they might be feral cats or weasels.

They never go to the beach; for women it’s a sin to swim in the sea, and a sin even to watch others swimming.

In books, the houses of ancient feudal cities, grouped together or scattered through the valley and across the hillsides, all in sight of the castle that dominates them from the highest peak, are often compared to a flock around the shepherd. Thus, too, on Procida, the houses—from those densely crowded at the port, to the ones spread out on the hills, and the isolated country farmhouses—appear, from a distance, exactly like a herd scattered at the foot of the castle. This castle rises on the highest hill (which among the other, smaller hills is like a mountain); and, enlarged by structures superimposed and added over the centuries, has acquired the mass of a gigantic citadel. To passing ships, especially at night, all that appears of Procida is this dark mass, which makes our island seem like a fortress in the middle of the sea.

For around two hundred years, the castle has been used as a penitentiary: one of the biggest, I believe, in the whole country. For many people who live far away the name of my island means the name of a prison.

On the western side, which faces the sea, my house is in sight of the castle, but at a distance of several hundred meters as the crow flies, and over numerous small inlets from which, at night, the fishermen set out in their boats with lanterns lighted. At that distance you can’t distinguish the bars on the windows, or the circuit of the guards around the walls; so that, especially in winter, when the air is misty and the moving clouds pass in front of it, the penitentiary might seem the kind of abandoned castle you find in many old cities. A fantastic ruin, inhabited only by snakes, owls, and swallows.

The Story of Romeo the Amalfitano

My house rises alone at the top of a steep hill, in the middle of an uncultivated terrain scattered with lava pebbles. The façade looks toward the town, and on that side the hill is buttressed by an old wall made of pieces of rock; here lives the deep blue lizard (which is found nowhere else, nowhere else in the world). On the right, a stairway of stones and earth descends toward the level ground where vehicles can go.

Behind the house there is a broad open space, beyond which the land becomes steep and impassable. And by means of a long rockslide you reach a small, triangular, black-sand beach. No path leads to this beach; but, if you’re barefoot, it’s easy to descend precipitously amid the rocks. At the bottom a single boat was moored: it was mine, and was called Torpedo Boat of the Antilles.

My house isn’t far from a small, almost urban square (boasting, among other things, a marble monument) or from the densely built dwellings of the town. But in my memory it has become an isolated place, and its solitude makes an enormous space around it. There it sits, malign and marvelous, like a golden spider that has woven its iridescent web over the whole island.

It’s a two-story palazzo, plus the cellar and the attic (in Procida houses that have around twenty rooms, which in Naples might seem small, are called palazzi), and, as with most of the inhabited area of Procida, which is very old, it was built at least three centuries ago.

It’s a pale pink color, square, rough, and constructed without elegance; it would look like a large farmhouse if not for the majestic central entrance and the Baroque-style grilles that protect all the windows on the outside. The façade’s only ornaments are two iron balconies, suspended on either side of the entrance, in front of two blind windows. These balconies, and also the grilles, were once painted white, but now they’re all stained and corroded by rust.

A smaller door is cut into one panel of the central entrance door, and this is the way we usually go in: the two panels are, instead, never opened, and the enormous locks that bolt them from the inside have been eaten by rust and are unusable. Through the small door you enter a long, windowless hall, paved with slate, at the end of which, in the style of Procida’s grand houses, a gate opens to an internal garden. This gate is guarded by two statues of very faded painted terra-cotta, portraying two hooded figures, which could be either monks or Saracens, you can’t tell. And, beyond the gate, the garden, enclosed by the walls of the house like a courtyard, appears a triumph of wild greenery.

There, under the beautiful carob tree, my dog Immacolatella is buried.

From the roof of the house, one can see the full shape of the island, which resembles a dolphin; its small inlets, the penitentiary, and not far away, on the sea, the bluish purple form of the island of Ischia. The silvery shadows of more distant islands. And, at night, the firmament, where Boötes the Herdsman walks, with his star Arturo.

From the day it was built, for more than two centuries, the house was a monastery: this fact is common among us, and there’s nothing romantic about it. Procida was always a place of poor fishermen and farmers, and its rare grand buildings were all, inevitably, either convents, or churches, or fortresses, or prisons.

Later, those religious men moved elsewhere, and the house ceased to belong to the Church. For a certain period, during and after the wars of the past century, it housed regiments of soldiers; then it was abandoned and uninhabited for a long time; and finally, about half a century ago, it was bought by a private citizen, a wealthy shipping agent from Amalfi, who, passing through Procida, made it his home, and lived there in idleness for thirty years.

He transformed part of the interior, especially the upper floor, where he knocked down the dividing walls between numerous cells of the former monastery and covered the walls with wallpaper. Even in my time, although the house was run-down and in constant disrepair, it preserved the arrangement and the furnishings as he had left them. The furniture, which had been collected by a picturesque but ignorant imagination from the small antique and secondhand dealers of Naples, gave the rooms a certain romantic-country aspect. Entering, you had the illusion of a past of grandmothers and great-grandmothers, of ancient female secrets.

And yet from the time those walls were erected until the year our family arrived, they had never seen a woman.

When, a little more than twenty years ago, my paternal grandfather, Antonio Gerace, who had emigrated from Procida, returned with a modest fortune from America, the Amalfitano, who by then was an old man, still lived in the ancient palazzo. In old age, he had become blind; and it was said that this was a punishment from Santa Lucia, because he hated women. He had hated them since youth, to the point that he wouldn’t receive even his own sisters, and when the Sisters of the Consolation came to beg he left them outside the door. For that reason, he had never married; and he was never seen in church, or in the shops, where women are more readily encountered.

He wasn’t hostile to society; in fact, he had quite a splendid character, and often gave banquets, and even masked parties, and on such occasions he proved to be generous to the point of madness, so that he had become a legend on the island. However, no woman was admitted to his entertainments; and the girls of Procida, envious of their boyfriends and brothers who took part in those mysterious evenings, spitefully nicknamed the Amalfitano’s abode the Casa dei Guaglioni, or Boys’ House (guaglione, in Neapolitan dialect, means boy or youth).

My grandfather Antonio, disembarking in his homeland after some decades of absence, did not think that destiny had reserved the Casa dei Guaglioni for his family. He scarcely recalled the Amalfitano, with whom he had never had a friendly relationship; and that old monastery-barracks among the thorns and prickly pears did not in the least resemble the dwelling he had dreamed of for himself during his exile. He bought a house in the country, with a farm, in the southern part of the island, and went to live there, alone with his tenant farmers, being a bachelor with no close relatives.

Actually, there existed on the earth one close relative of Antonio Gerace, whom he had never seen. This was a son, born during his early life as an emigrant, from a relationship with a young German schoolteacher, whom he soon abandoned. For several years after the abandonment (the emigrant had moved to America following a short stint in Germany), the girl-mother had continued to write to him, begging him for material help, because she found herself without work, and seeking to move him with marvelous descriptions of the child. But the emigrant was himself so wretched at the time that he stopped answering the letters, until the young woman, discouraged, stopped writing. And when, returning to Procida aged and without heirs, Antonio tried to find her, he learned that she had died, leaving the child, now around sixteen, in Germany.

Antonio Gerace then summoned that son to Procida, to finally give him his own name and his own inheritance. And so he who was to become my father disembarked on the island of Procida, dressed in rags like a gypsy (I learned later).

He must have had a hard life. And his childish heart must have been nourished on rancor not only toward his unknown father but also toward all the other innocent Procidans. Maybe, too, by some act or behavior, they affronted his irascible pride from the start, and forever. Certainly, on the island, his indifferent and offensive manner made him universally hated. With his father, who tried to win his affection, the boy was aloof to the point of cruelty.

The only person on the island he saw was the Amalfitano. It was some time since the latter had given entertainments or parties, and he lived isolated in his blindness, surly and proud, refusing to receive those who sought him out and pushing away with his stick those who approached him on the street. His tall, melancholy figure had become detested by everyone.

His house opened again to only one person: the son of Antonio Gerace, who formed such a close friendship with him that he spent every day in his company, as if the Amalfitano, and not Antonio Gerace, were his real father. And the Amalfitano devoted to him an exclusive and tyrannical affection: it seemed that he couldn’t live a day without him. If the son was late in his daily visit, the Amalfitano went out to meet him, sitting at the end of the street to wait. And, unable to see if he was finally coming, in his blind man’s anxiety he would every so often call out his name, in a hoarse voice that seemed already to come from the grave. If passersby answered that Gerace’s son wasn’t there, he would throw some coins and banknotes on the ground, haphazardly and with contempt, so that, thus paid, they would go and summon him. And if they returned later to say that they hadn’t found him at home, he had them search the entire island, even unleashing his dogs in the hunt. In his life now there was nothing else: either being with his only friend or waiting for him. Two years later, when he died, he left him the house on Procida.

Not long afterward, Antonio Gerace died: and the son, who some months earlier had married an orphan from Massa, moved to the Amalfitano’s house with his young, pregnant bride. He was then about nineteen, and the wife not yet eighteen. It was the first time, in almost three centuries since the palazzo was built, that a woman had lived within its walls.

The farmers remained in my grandfather’s house and on his land, and are still tenants there today.

The Boys’ House

The premature death of my mother, at eighteen, giving birth to her first child, was certainly a confirmation, if not the origin, of a popular rumor according to which the deceased owner’s hatred meant that it was forever fatal for a woman to live in the Casa dei Guaglioni, the Boys’ House, or even simply to enter it.

My father had barely a faint smile of scorn for that country tale, so that I, too, from the start learned to consider it with the proper contempt, as the superstitious nonsense it was. But it had acquired such authority on the island that no woman would ever agree to be our servant. During my childhood a boy from Naples worked for us; his name was Silvestro, and at the time he entered our house (shortly before my birth) he was fourteen or fifteen. He returned to Naples at the time of his military service, and was replaced by one of our tenant farmers, who came only a couple of hours a day, to do the cooking. No one gave any thought to the dirt and disorder of the rooms, which to us seemed natural, like the vegetation of the uncultivated garden within the walls of the house.

It’s impossible to give an accurate picture of this garden (today the cemetery of my dog Immacolatella). Around the adult carob could be found, among other things, the rotting frames of old furniture covered with mosses, broken dishes, demijohns, oars, wheels, and so on. And amid the rocks and the debris grew plants with distended, thorny leaves, sometimes beautiful and mysterious, like exotic specimens. After the rains, hundreds of flowers of more noble stock bloomed, from seeds and bulbs planted there long ago. And in the summer drought everything blackened, as if burned.

In spite of our affluence, we lived like savages. A couple of months after my birth, my father had departed from the island for an absence of almost half a year: leaving me in the arms of our first boy, who was very serious for his age and raised me on goat’s milk. It was the same boy who taught me to speak, to read and write; and then, reading the books I found in the house, I educated myself. My father never cared to make me go to school: I was always on vacation, and my days of wandering, especially during his long absences, ignored any rule or schedule. Only hunger and sleep signaled the time to return home.

No one thought to give me money, and I didn’t ask for it; besides, I didn’t feel a need for it. I don’t remember ever possessing a cent, in all my infancy and childhood.

The farm inherited from my grandfather Gerace provided the foods necessary for our cook: who didn’t depart too far from the primitive and the barbarian in the arts of the kitchen. His name was Costante; and he was as taciturn and rough as his predecessor, Silvestro (the one I could, in a certain sense, call my nurse), had been gentle.

Winter evenings and rainy days I occupied with reading. After the sea and roaming around the island, I liked reading best. Usually I read in my room, lying on the bed, or on the sofa, with Immacolatella at my feet.

Our rooms gave onto a narrow hall, along which, at one time, the brothers’ cells (perhaps twenty in all) had opened. The former owner had knocked down most of the walls between the cells in order to make the rooms more spacious; but (perhaps charmed by their decorations and carvings) had left some of the old doors intact. So, for example, my father’s room had three doors, all in a row along the hall, and five windows, similarly in a line. Between my room and my father’s, one cell had been preserved in its original dimensions, and there, during my childhood, the boy Silvestro slept. His sofa bed (or, to be clearer, a sort of cot) was still there, together with the empty chest for storing pasta where he put his clothes.

As for my father and me, we didn’t put our clothes anywhere. Our rooms had dressers and wardrobes available, which, if you opened them, threatened to collapse, and emitted the odors of some extinct Bourbon bourgeoisie. But these pieces of furniture were of no use to us, except, sometimes, for tossing no longer serviceable objects that cluttered the rooms—for example, old shoes, broken fishing rods, shirts reduced to rags, and so on. Or storing booty: fossil shells, from the time when the island was still a submarine volcano; cartridge cases; bottoms of bottles mottled by the sand; pieces of rusted engines. And subaqeous plants, and starfish, which later dried out or rotted in the musty drawers. Maybe that’s partly why I’ve never recognized the smell of our rooms anywhere else, in any human space or even in the dens of earthly animals; maybe, rather, I’ve found something similar in the bottom of a boat, or in a cave.

Those enormous dressers and wardrobes, occupying a large part of the free wall space, barely left a place for the beds, which were the usual iron bedsteads, with decorations of mother-of-pearl or painted landscapes, such as are found in all the bedrooms of Procida and Naples. Our winter blankets, in which I slept wrapped up, as if in a sack, were full of moth holes; and the mattresses, which were never plumped or carded, were flattened with use, like sheets of dough.

I recall that every so often, using a pillow or an old leather jacket that had belonged to Silvestro as a broom, my father, with my help, swept up from around his bed the old cigarette butts, which we piled in a corner of the room and later threw out the window. It was impossible to say in our house what material or color the floor was, because it was hidden under a layer of hardened dust. Similarly, the windowpanes were all blackened and opaque; suspended high up in the corners and between the window grilles the iridescence of spider webs was visible, shining in the light.

I think that the spiders, the lizards, the birds, and in general all non-human beings must have considered our house an uninhabited tower from the time of Barbarossa, or even a rocky protrusion rising from the sea. Along the outside walls, lizards emerged from cracks and secret furrows as from the earth; countless swallows and wasps made nests there. Birds of foreign species, passing over the island on their migrations, stopped to rest on the windowsills. And even the seagulls came to dry their feathers on the roof after their dives, as if on the mast of a ship or the top of a cliff.

At least one pair of owls lived in our house, although it was impossible for me to discover where; but it’s a fact that, as soon as evening descended, you could see them flying out of the walls, with their entire family. Other owls, of different species, came from far away to hunt in our land, as in a forest. One night, an immense owl, an eagle owl, came to rest on my window. From its size I thought for a moment that it was an eagle; but it had much paler feathers, and later I recognized it from its small upright ears.

In some of the uninhabited rooms of the house, the windows, forgotten, stayed open in all seasons. And, entering those rooms unexpectedly, at an interval of months, you might encounter a bat, or hear the cries of mysterious broods hidden in a chest or among the rafters.

Certain curious creatures turned up, species never seen on the island. One morning, I was sitting on the ground behind the house, pounding almonds with a stone, when I saw emerge, up from the rockslide, a small, very pretty animal, of a species between a cat and a squirrel. It had a large tail and a triangular snout with white whiskers, and it observed me attentively. I threw it a shelled almond, hoping to ingratiate myself. But my gesture frightened it, and it fled.

Another time, at night, looking out over the edge of the slope, I saw a bright white quadruped, the size of a medium tuna, advancing up from the sea toward our house; it had curved horns, which looked like crescent moons. As soon as it became aware of me it turned back and disappeared amid the cliffs. I suspected that it was a dugong, a rare species of amphibious ruminant, which some say never existed, others that it is extinct. Many sailors, however, are sure they’ve often seen one of these dugongs, which lives in the neighborhood of the Grotta Azzurra of Capri. It lives in the sea like a fish, but is greedy for vegetables, and during the night comes out of the water to steal from the farms.

As for visits from humans, Procidans or foreigners, the Casa dei Guaglioni had not received any for years.

On the first floor was the brothers’ former refectory, transformed by the Amalfitano into a reception room. It was an enormous space, with a high ceiling, almost twice the height of the other rooms, and windows that were high off the ground and looked toward the sea. The walls, unlike those of the other rooms, were not covered with wallpaper but decorated all around by a fresco, which imitated a columned loggia, with vine shoots and bunches of grapes. Against the back wall there was a table more than six meters long, and scattered everywhere were broken-down sofas and chairs, seats of every style, and faded cushions. One corner was occupied by a large fireplace, which we never used. And from the ceiling hung an immense chandelier of colored glass, caked with dust: only a few blackened bulbs were left, so that it gave off the same light as a candle.

It was here that in the days of the Amalfitano, amid music and singing, the groups of youths had their gatherings. The room still bore traces of their celebrations, and faintly recalled the great halls of villas occupied by the conquerors in war or, in some respects, the assembly halls in prisons—and in general all the places where youths and boys gather together without women. The worn, dirty fabrics covering the sofas showed cigarette burns. And on the walls, as well as on the tables, there were inscriptions and drawings: names, signatures, jokes, and expressions of melancholy or of love, and lines from songs. Then a pierced heart, a ship, the figure of a soccer player balancing the ball on his toes. And some humorous drawings: a skull smoking a pipe, a mermaid sheltering under an umbrella, and so on.

Numerous other drawings and inscriptions had been scratched off, I don’t know by whom; the scars of the erasures remained visible on the plaster and on the wooden tables.

In other rooms, too, similar traces of past guests could be found. For example, in a small unused room, you could still read on the wallpaper above an alabaster stoup (left from the time of the monastery) a faded ink signature surrounded by flourishes: “Taniello.” But, apart from these unknown signatures and worthless drawings, nothing else could be found, in the house, to bear witness to the time of parties and banquets. I learned that after the death of the shipping agent many Procidans who had taken part in those celebrations in their youth showed up at the Casa dei Guaglioni to demand objects and souvenirs. They claimed, vouching for one another, that the Amalfitano had promised them as gifts for the day of his death. So there was a kind of sack; and perhaps it was then that the costumes and masks were carried off, which are even now much talked about on the island; and the guitars, and mandolins, and glasses with toasts written in gold on the crystal. Maybe some of these spoils have been saved, in the cottages of peasants or fishermen. And the women of the family, now old, look with a sigh at such mementos, feeling again the jealousy they felt as girls of the mysterious revels from which they were excluded. They’re almost afraid to touch those dead objects, which might contain in themselves the hostile influence of the Casa dei Guaglioni!

Another mystery was what became of the Amalfitano’s dogs. It’s known that he had several, and loved them; but at his death they disappeared from the house without a trace. Some assert that, after their master was carried to the cemetery, they grew sad, refusing food, and were all left to die. Others say that they began to roam the island like wild beasts, growling at anyone who approached, until they all became rabid, and the wardens captured them one by one, and killed them, throwing them off a cliff.

Thus the things that had happened in the Casa dei Guaglioni before my birth came down to me indistinctly, like adventures from long-ago centuries. Even of my mother’s brief stay (aside from the photograph that Silvestro had saved for me) I could find no sign in the house. From Silvestro himself I learned that one day when I was around two months old, and my father had recently departed on his travels, some relatives from Massa arrived, apparently peasants, who carried off everything that had belonged to my mother, as if it were their lawful inheritance: her trousseau, brought as a dowry, her clothes, and even her clogs and her mother-of-pearl rosary. They certainly took advantage of the fact that there was no adult in the house to resist: and Silvestro at a certain point was afraid that they wanted to carry me off, too. So, on some pretext, he hurried to his cell, where he had put me to sleep on the bed, and quickly hid me in the old pasta crate where he kept his clothes (and whose battered cover let in air). Next to me he put the bottle of goat’s milk, so that if I woke up I would be quiet and give no sign of my presence. But I didn’t wake up, staying silent during the entire visit of the relatives, who, besides, weren’t much concerned to have news of me. Only on the point of leaving with their bundle of things, one of them, more out of politeness than anything else, asked if I was growing well and where I was: and Silvestro answered that I had been put out to nurse. They were satisfied with that and, returning forever to Massa, were not heard from again.

And so passed my solitary childhood, in the house denied to women.

In my father’s room there is a large photograph of the Amal fitano. It portrays a slender old man, enveloped in a long jacket, with unfashionable pants that allow a glimpse of white stockings. His white hair falls behind his ears like a horse’s mane, and his high, smooth forehead, struck by the light, has an unnatural whiteness. His lifeless, open eyes have the clear, enraptured expression of certain animal eyes.

The Amalfitano chose a calculated, bold pose for the photographer. He is taking a step, and hints at a gallant smile, as if in greeting. With his right hand, he raises an iron-tipped black stick, which he is in the act of twirling; and with the left he holds two large dogs on a leash. Under the portrait, in the shaky hand of a semiliterate blind old man, he has written a dedication to my father:

TO WILHELM ROMEO

This photograph of the Amalfitano reminded me of the figure of Boötes, Arturo’s constellation, as it was drawn on a big map of the northern hemisphere in an astronomy atlas that we had in the house.

Beauty

What I know about my father’s origins I learned when I was already grown. Since I was a boy, I’d occasionally heard the people of the island call him “bastard,” but that word sounded to me like a title of authority and mysterious prestige: such as “margrave,” or some similar title. For many years, no one ever told me anything about the past of my father and grandfather: the Procidans are not loquacious, and, at the same time, following my father’s example, I kept my distance from the island’s inhabitants, and had no friends among them. Costante, our cook, was a presence more animal than human. In the many years that he worked for us, I don’t remember ever exchanging with him two words of conversation; and, besides, I very rarely saw him. When his work in the kitchen was done, he returned to the farm; and I, coming home when I felt like it, found his simple dishes waiting for me, now cold, in the empty kitchen.

Most of the time, my father lived far away. He would come to Procida for a few days, and then leave again, sometimes remaining absent for entire seasons. If at the end of the year you made a summary of his rare, brief sojourns on the island, you would find that, out of twelve months, he had been on Procida, with me, for perhaps two. Thus I spent almost all my days in absolute solitude; and this solitude, which began in early childhood (with the departure of my nurse Silvestro), seemed to me my natural condition. I considered my father’s every sojourn on the island an extraordinary favor on his part, a special concession that I was proud of.

I believe I had barely learned to walk when he bought me a boat. And one day when I was about six, he brought me to the farm, where the farmer’s shepherd bitch was nursing her month-old puppies, so that I could choose one. I chose the one that seemed to me the most high-spirited, with the friendliest eyes. It turned out to be a female; and since she was white, like the moon, she was called Immacolatella.

As for providing me with shoes, or clothes, my father seldom remembered. In the summer, I wore no other garment than a pair of trousers, in which I also dove into the water, letting the air dry them on me. Only occasionally did I add to the trousers a cotton shirt that was too short, and all torn and loose. Unlike me, my father possessed a pair of khaki bathing trunks; but, apart from that, he, too, in summer, wore nothing but some old faded trousers and a shirt that no longer had a single button, and fell open over his chest. Sometimes he knotted around his neck a flower-patterned kerchief, of the type that peasant women buy at the market for Sunday Mass. And that cotton rag, on him, seemed to me the mark of a leader, a wreath of flowers that declared the glorious conqueror!

Neither he nor I owned a coat. In winter, I wore two sweaters, one over the other, and he a sweater underneath and, on top, a threadbare, shapeless checked wool jacket, with excessively padded shoulders that increased the authority of his height. The use of underwear was almost completely unknown to us.

He had a wristwatch (with a steel case and a heavy steel-link wristband), which also marked the seconds and could even be worn in the water. He had a mask for looking underwater when you were swimming, a speargun, and naval binoculars with which you could distinguish the ships traveling on the high sea, along with the figures of sailors on the bridge.

My childhood is like a happy land, and he is the absolute ruler! He was always passing through, always leaving; but in the brief intervals that he spent on Procida I followed him like a dog. We must have been a comical pair, for anyone who met us! He advancing with determination, like a sail in the wind, with his fair-haired foreigner’s head, his lips in a pout and his eyes hard, looking no one in the face. And I behind, turning proudly to right and left with my dark eyes, as if to say: “Procidans, my father is passing by!” My height, at that time, was not much beyond a meter, and my black hair, curly as a gypsy’s, had never known a barber. (When it got too long, I shortened it energetically with the scissors, in order not to be taken for a girl; only on rare occasions did I remember to comb it, and in the summer it was always encrusted with sea salt.)

Our pair was almost always preceded by Immacolatella, who ran ahead, turned back, sniffed all the walls, stuck her muzzle in all the doors, greeted everyone. Her friendliness toward our fellow citizens often made me impatient, and with imperious whistles I recalled her to the rank of the Geraces. I thus had occasion to practice whistling. Since I’d lost my baby teeth, I’d become a master of the art. Putting index and middle fingers in my mouth, I could draw out martial sounds.

I could also sing reasonably well; and from my nurse I had learned various songs. Sometimes, while I walked behind my father or was out in the boat with him, I sang over and over again “Women of Havana,” “Tabarin,” “The Mysterious Sierra,” or Neapolitan songs, for example the one that goes: Tu si’ ’a canaria! Tu si’ ll’amore! (You’re the canary! You’re love!), hoping that in his heart my father would admire my voice. He gave no sign even of hearing it. He was always silent, brusque, touchy, and reluctantly conceded me a glance or two. But it was already a great privilege for me that the only company tolerated by him on the island was mine.

In the boat, he rowed, and I monitored the route, sitting in the stern or astride the prow. Sometimes, intoxicated by that divine happiness, I let go, and with enormous presumption began to give orders: Go, right oar! Go, with the left! Back-oar! But if he raised his eyes to look at me his silent splendor reminded me how small I was. And it seemed to me that I was a minnow in the presence of a great dolphin.

The primary reason for his supremacy over all others lay in his difference, which was his greatest mystery. He was different from all the men of Procida, that is to say from all the people I knew in the world, and also (O bitterness) from me. Mainly he stood out from the islanders because of his height. (But that height revealed itself only in comparison, if you saw him near others. When he was alone, isolated, he seemed almost small, his proportions were so graceful.)

Besides his height, his coloring distinguished him. His body in summer acquired a gentle brown radiance, drinking in the sun, it seemed, like an oil; but in winter he became as pale as a pearl. And I, who was dark in every season, saw in that something like the sign of a race not of the earth: as if he were the brother of the sun and the moon.

His hair was soft and smooth, of an opaque blond, which in certain lights glinted with gem-like highlights; and on the nape, where it was shorter, almost shaved, it was truly gold. Finally, his eyes were a blue-violet that resembled the color of certain expanses of the sea darkened by clouds.

That beautiful hair of his, always dusty and disheveled, fell in locks over his wrinkled brow, as if to hide his thoughts with their shadow. And his face, which preserved, through the years, the energetic forms of adolescence, had a closed and arrogant expression.

Sometimes a flash of the jealous secrets that his thoughts seemed always intent on passed over his face: for example, a rapid, wild, and almost gratified smile; or a slightly devious and insulting grimace; or an unexpected ill humor, without apparent cause. For me, who could not attribute to him any human whim, his brooding was grand, like the darkening of the day, a sure sign of mysterious events, as important as universal history.

His motives belonged to him alone. For his silences, his celebrations, his contempt, his sufferings I did not seek an explanation. They were, for me, like sacraments: great and grave, beyond any earthly measure and any frivolity.

If, let’s say, he had shown up one day drunk, or delirious, I would surely have been unable to imagine, even with that, that he was subject to the common weaknesses of mortals! Like me, he never got sick, as far as I remember; however, if I had seen him sick, his illness would not have seemed to me one of the usual accidents of nature. It would have assumed, in my eyes, almost the sense of a ritual mystery, in which Wilhelm Gerace was the hero, and the priests summoned to be present received the privilege of a consecration! And certainly I would not have doubted, I believe, that some upheaval of the cosmos, from the earthly lands to the stars, was bound to accompany that paternal mystery.

There is, on the island, a stretch of level ground surrounded by tall rocks where there’s an echo. Sometimes, if we happened to go there, my father amused himself by shouting phrases in German. Although I didn’t know their meaning, I understood, from his arrogant expression, that they must be terrible, rash words: he flung them out in a tone of defiance and almost profanation, as if he were violating a law, or breaking a magic spell. When the echo came back to him, he laughed, and let out more brutal words. Out of respect for his authority, I didn’t dare to second him, and although I trembled with warlike anxiety, I listened to those enigmas in silence. It seemed to me that I was present not at the usual game of echoes, common among boys, but at an epic duel. We’re at Roncesvalles, and suddenly Orlando will erupt onto the plain with his horn. We’re at Thermopylae and behind the rocks the Persian knights are hiding, in their pointed caps.

When, on our rounds through the countryside, we came to an upward slope, he would be seized by impatience and take off at a run, with the determination of a wonderful task, as if he were climbing the mast of a sailboat. And he didn’t care to know if I was behind him or not; but I followed at breakneck speed, with the disadvantage of my shorter legs, and joy kindled my blood. That was not one of the usual runs I did, countless times a day, competing with Immacolatella. It was a famous tournament. Up there a cheering finish line awaited us, and all thirty million gods!

His vulnerabilities were as mysterious as his indifference. I remember that once, while we were swimming, he collided with a jellyfish. Everyone knows the result of such an accident: a brief, inconsequential reddening of the skin. He, too, surely knew that; but, seeing his chest marked by those bloody stripes, he was stricken by a horror that made him go pale to his lips. He fled immediately to the shore and threw himself faceup on the ground, arms spread, like one already overwhelmed by the nausea of the death agony! I sat beside him: I myself had more than once been the victim of sea urchins, jellyfish, and other marine creatures, giving no importance to their injuries. But that day, when he was the victim, a solemn sense of tragedy invaded me. A vast silence fell over the beach and the whole sea, and in it the cry of a passing seagull seemed to me a female lament, a Fury.

The Absolute Certainties

He scorned to win my heart. He left me in ignorance of German, his native tongue; with me, he always used Italian, but it was an Italian different from mine, which Silvestro had taught me. All the words he spoke seemed to be just invented, and still undomesticated; and even my Neapolitan words, which he often used, became, uttered by him, bolder and new, as in poems. That strange language gave him, for me, the charm of the Sibyls.

How old was he? Around nineteen years older than me! His age seemed serious and respectable, like the holiness of the Prophets or of King Solomon. Every act of his, every speech, had a dramatic fatality for me. In fact, he was the image of certainty, and everything he said or did was the verdict of a universal law from which I deduced the first commandments of my life. Here was the greatest seduction of his company.

By birth he was a Protestant; but he professed no faith, displaying a sullen indifference toward Eternity and its problems. I’ve been a Catholic, on the other hand, since I was a month old, on the initiative of my nurse Silvestro, who took care, at the time, to have me baptized in the parish church at the port.

That was, I think, the first and last time I visited a church as a Christian subject. I liked at times to linger in a church, as in a beautiful aristocratic room, in a garden, on a ship. But I would have been ashamed to kneel, or perform other ceremonies, or pray, even only in thought: as if I could truly believe that that was the house of God, and that God is in communication with us, or even exists!

My father had received some education, thanks to the teacher, his girl-mother; and he possessed (in large part inherited from her) some books, including some in Italian. To this small family library were added, in the Casa dei Guaglioni, numerous volumes left there by a young literature student who for many summers had been a guest of Romeo the Amalfitano. Not to mention various novels suitable for youthful taste, mysteries and adventure stories of differing provenance. And so I had available a respectable library, even if it was made up of battered old volumes.

They were, for the most part, classics, or scholastic or educational texts: atlases and dictionaries, history books, narrative poems, novels, tragedies, and poetry collections, and translations of famous works. Apart from the texts incomprehensible to me (written in German or Latin or Greek), I read and studied all these books; and some, my favorites, I reread many times, so that even today I remember them almost by heart.

Among the many teachings, then, that I got from my readings, I chose on my own the most fascinating, and those were the teachings that best corresponded to my natural feeling about life. With those and, in addition, the early certainties that the person of my father had already inspired in me, a kind of Code of Absolute Truth took shape in my consciousness, or imagination, whose most important laws could be listed like this:

I. THE AUTHORITY OF THE FATHER IS SACRED!

II. TRUE MANLY GREATNESS CONSISTS IN THE COURAGE TO ACT, IN DISDAIN FOR DANGER, AND IN VALOR DISPLAYED IN COMBAT.

III. THE BASEST ACT IS BETRAYAL. THUS ONE WHO BETRAYS HIS OWN FATHER OR LEADER, OR A FRIEND, ETC., HAS REACHED THE LOWEST POINT OF DEPRAVITY!

IV. NO LIVING CITIZEN ON THE ISLAND OF PROCIDA IS WORTHY OF WILHELM GERACE AND HIS SON ARTURO. FOR A GERACE TO BE FRIENDLY TOWARD A FELLOW CITIZEN WOULD BE TO DEBASE HIMSELF.

V. NO AFFECTION IN LIFE EQUALS A MOTHER’S.

VI. THE CLEAREST PROOFS AND ALL HUMAN EXPERIENCES DEMONSTRATE THAT GOD DOES NOT EXIST.

The Second Law

These boyhood certainties of mine were for a long time not only what I honored and loved but the substance of the only possible reality for me! In those years, to live outside my great certainties would have appeared to me not only dishonorable but impossible.

However, lacking a suitable interlocutor with whom to discuss them intimately, I had never said a word about them to anyone in the world. My Code had remained my jealous secret: and this, certainly, out of superiority and pride, was a good quality; but it was also a difficult quality. Another difficult quality of my Code was a reticence. None of my laws, I mean, named the thing I hated most: that is, death. That reticence was, on my part, a sign of elegance and of contempt for that hated thing, which could only insinuate itself into the words of my laws in a devious manner, like a pariah or a spy.

In my natural happiness, I avoided all thoughts of death, as of an impossible figure with horrendous vices: hybrid, abstruse, full of evil and shame. But, at the same time, the more I hated death, the more fun I had and the more pleasure I got from attempting proofs of daring: in fact, I disliked any game that didn’t include the fascination of risk. And so I had grown up in that contradiction: loving valor, hating death. It may be, though, that it wasn’t a contradiction.

All reality appeared to me clear and distinct: only the abstruse stain of death muddied it; and so my thoughts, as I said, retreated with horror at that point. On the other hand, with a similar horror I thought I recognized a perhaps fatal sign of my immaturity, like fear of the dark in ignorant girls (immaturity was my shame). And I waited, as for a sign of marvelous maturity, for that unique muddiness—death—to dissolve into the clarity of reality, like smoke into transparent air.

Until that day, I could consider myself only, in essence, an inferior, a boy; and meanwhile, as if drawn in by the insidious pull of a mirage, I ran wild, a little hooligan (as my father said), in every kind of childish exploit … But such bold acts, naturally, could not suffice, in my judgment, to promote me to the envied rank (maturity) or free me from an inner and supreme doubt of myself.

In fact, it was in essence always a matter of games; death, there, was still a stranger to me, almost an unreal fantasy. How would I behave at the true test, in war, for example, when I really saw that murky, monstrous stain advancing, growing larger, before me?

Thus, a skeptic in my games of childish daring, from the start I always waited at the ultimate challenge, like a provocateur and rival of myself. Maybe, was it because I was only a vain kid and no more (as W.G. once accused me of being)? Maybe, was my precocious bitterness toward death, which shadowed me and tempted me to redemption, nothing but the anxiety to be pleasing to myself to the point of perdition—the same anxiety that destroyed Narcissus?

Or maybe, instead, was it only a pretext? There is no answer. And, besides, it’s my business. In conclusion: in my Code, the Second Law (where the famous reticence huddled more naturally, as in its den) counted most of all for me.

The Fourth Law

The Fourth Law, suggested to me by my father’s attitude, was, perhaps along with my natural inclination, evidently the original cause of my Procidan solitude. I seem to see again my small figure of the time wandering around at the port, amid the traffic and the movement of people, with an expression of mistrustful and surly superiority, like a stranger who finds himself in the middle of a hostile population. The most demeaning feature I noted, in that population, was a permanent dependence on practical necessity; and that feature made the glorious and different species of my father stand out even more! There not only the poor but the rich as well seemed constantly preoccupied by their present interests or earnings: all of them, from the ragged kids who scuffled for a coin, or a crust of bread, or a colored pebble, to the owners of fishing boats, who discussed the price of fish as if that were the most important value of their existence. No one among them, evidently, was interested in books, or in great actions! Sometimes the schoolboys were lined up in an open space by the teacher for pre-military exercises. But the teacher was fat and sluggish, the boys displayed neither ability nor enthusiasm, and the whole spectacle, from the uniforms to the actions and the methods, appeared so unmartial, in my judgment, that I immediately looked away with a sense of pain. I would have blushed with shame if my father, turning up at that moment, had surprised me looking at certain scenes and certain characters!

The Prison Fortress

The only inhabitants of the island who did not seem to arouse my father’s contempt and antipathy were the invisible, unnamed inmates of the prison. In fact, certain of his romantic and terrible habits might let me suppose that a kind of brotherhood, or code of silence, bound him not only to them but to all the life convicts and imprisoned of the earth. And I, too, of course, was on their side, not only in imitation of my father but from a natural inclination, which made prison seem an unjust, absurd monstrosity, like death.

The prison fortress was a kind of grim and sacred domain, and thus forbidden; and I don’t remember that, during all my childhood and adolescence, I ever entered alone. Sometimes, as if enthralled, I started up the ascent that led to it, and then, as soon as I saw those gates, I fled.

I recall that, during walks with my father in those days, I had perhaps once or twice passed through the gates of the fortress and traversed its solitary spaces. And in my childhood memory those rare excursions were like journeys through a region far from my island. Following my father, I looked furtively from the deserted roadway toward those barred slits of windows like air vents, or glimpsed, behind an infirmary grille, the mournful white color of a prisoner’s uniform … and immediately turned away my gaze. Curiosity, or even mere interest, on the part of free and happy people seemed to me insulting to the prisoners. The sun, on those streets, was an insult, and up there the roosters crowing on the balconies of the cottages, the doves cooing along the cornices irritated me, with their tactless insolence. Only my father’s freedom did not seem offensive, but, on the contrary, comforting, like an assurance of happiness, the only one on that sad height. With his rapid, graceful gait, slightly swaying like a sailor’s, and his blue shirt swelling in the wind, he seemed to me the messenger of a victorious adventure, of an enchanting power. In the depths of my feelings, I was almost convinced that only a mysterious contempt, or carelessness, kept him from exercising his heroic will, beating down the gates of the prison and freeing the prisoners. Truly, I could imagine no limits to his dominion. If I had believed in miracles, I would surely have considered him capable of performing them. But, as I’ve already revealed, I didn’t believe in miracles or in occult powers, to which some people entrust their fate, the way shepherd girls entrust it to the witches or the fairies!

Pointless Acts of Bravado

The books I liked most, needless to say, were those which celebrated, with real or imagined examples, my ideal of human greatness, whose living incarnation I recognized in my father.