Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

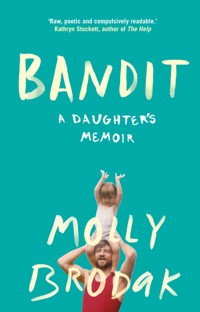

'Raw, poetic and compulsively readable ... I can't wait to buy a copy for everyone I know.' Kathryn Stockett, author of The Help The summer she turned thirteen, Molly Brodak's father was arrested for robbing eleven banks. In time, the image she held of him would unravel further, as more and more unexpected facets of his personality came to light. Bandit is her attempt to discover what, exactly, is left, when the most fundamental relationship of your life turns out to have been built on falsehoods. It is also a scrupulously honest account of learning how to trust again, and to rebuild the very idea of family from scratch. Refusing to fence off the trickier sides of her father's character, Brodak tries to find, through crystalline, spellbinding prose, a version of him that does not rely on the easy answers but allows him to be: an unknowable and incomprehensible whole – who is also her father. Unforgettable, moving, and utterly relatable, Bandit is a story of the unpredictable complexity of family.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 329

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BANDIT

A DAUGHTER’S MEMOIR

MOLLY BRODAK

Published in the UK in 2016 by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre, 39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP email: [email protected]

First published in the USA in 2016 by Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, N.Y. 10011

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House, 74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia by Grantham Book Services, Trent Road, Grantham NG31 7XQ

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District, 41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India, 7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City, Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

Portions of this book originally appeared inLIT, the Fanzine, and Granta.

The epigraph to this book is an excerpt from “XVII. Sometimes above the gross and palpable things of this diurnal sphere wrote Keats (Not a doctor but he danced as an apothecary) who also recommended strengthening the intellect by making up one’s mind about nothing” from The Beauty of the Husband by Anne Carson. Published by Jonathan Cape and reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Ltd and Anne Carson. All rights reserved.

The Friedrich Nietzsche quote that appears on page 168 is an excerpt from Ecce Home: How One Becomes What Is by Friedrich Nietzsche, translated with notes by R. J. Hollingdale, introduction by Michael Tanner (Penguin Classics 1979, Revised 1992). Translation copyright © R. J. Hollingdale, 1979. New introduction and text revisions copyright © Michael Tanner, 1992. Reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd

The Walter Benjamin quote that appears on page 260 is an excerpt from “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire” from Illuminations by Walter Benjamin, translated by Harry Zohn, English translation copyright © 1968 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

ISBN: 978-178578-103-2

Text copyright © 2016 Molly Brodak

The author has asserted her moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

For Boo

Fiction forms what streams in us. Naturally it is suspect.

—Anne Carson, The Beauty of the Husband

1

I was with my dad the first time I stole something.

It was a little booklet of baby names. I was seven and I devoured word lists: dictionaries, vocabulary sheets, menus. The appeal of this string of names, their pleasing shapes and neat order, felt like a puzzle impossible to solve. I couldn’t ask for it but I couldn’t leave it. I pressed it to my chest as we walked out of Kroger. It was pale blue with the word BABY spelled out in pastel blocks above a stock photo of a smiling white baby in a white diaper. I stood next to Dad, absorbed in page one, as he put the bags in the trunk of his crappy gold Chevette, and he stopped when he saw it. At first he said nothing. He avoided my eyes. He just pressed hard into my back and marched me back into the store, to the lane we’d left, plucked the stupid booklet out of my hand, and presented it to the cashier.

“My daughter stole this. I apologize for her.” He beamed a righteous look over a sweep of people nearby. The droopy cashier winced and muttered that it was OK, chuckling mildly. Then stooping over me he shouted, “Now you apologize. You will never do this again.” The cold anger in his face was edged with some kind of glint I didn’t recognize. As he gripped my shoulders he was almost smiling. I remember his shining eyes above me and the high ceiling of the gigantic store and the brightness of it. I am sure I cried but I don’t remember. I do remember an acidic boiling in my chest and a rinse of sweaty cold on my skin, disgusted with my own desire and what it did, how awful all of us felt now because of me. I didn’t steal again until I was a teenager, when he was in prison.

2

Dad robbed banks one summer.

He robbed the Community Choice Credit Union on 13 Mile Road in Warren.

He robbed the Warren Bank on 19 Mile Road.

He robbed the NBD Bank in Madison Heights.

He robbed the NBD Bank in Utica.

He robbed the TCF Bank on 10 Mile Road in Warren.

He robbed the TCF Bank on 14 Mile Road in Clawson, where I would open my first checking account when I turned seventeen. That’s the one with the little baskets of Dum-Dums at each window and the sour herb smell from the health food store next door.

He robbed the Credit Union One on 15 Mile Road in Sterling Heights.

He robbed the Michigan First Credit Union on Gratiot in Eastpointe.

He robbed the Comerica Bank on 8 Mile and Mound. That was as close as he got to the Detroit neighborhood he grew up in, Poletown East, about ten miles south.

He robbed the Comerica Bank inside a Kroger on 12 Mile and Dequindre. All of the shoppers gliding by as Dad passed a note to the teller in silence: “This is a robbery, I have a gun.”

He robbed the Citizens State Bank on Hayes Road in Shelby Township. Afterward the cops caught up with him finally, at Tee-J’s Golf Course on 23 Mile Road. They peeked into his parked car: a bag of money and his disguise in the backseat, plain as day. He was sitting at the bar, drinking a beer and eating a hot ham sandwich.

I was thirteen that summer. He went to prison for seven years after a lengthy trial, delayed by constant objections and rounds of him firing his public defenders. After his release he lived a normal life for seven years, and then robbed banks again.

3

There: see? Done with the facts already. The facts are easy to say; I say them all the time. They leave me out. They cover over the trouble like a lid. This isn’t about them.

This is about whatever is cut from the frame of narrative. The fat remnants, broke bones, gristle, untender bits. Me, and Mom, and my sister, and him, the actual him beyond the Bandit version on the evening news.

I see my little self there, under the stories. It’s 1987 and I am set between my parents like a tape recorder: Dad on the couch, fixed to the TV, Mom leaning in from the kitchen, me in between on the clumpy beige carpet with spelling worksheets. I am writing out the word people, watching the word slip off of my pencil lead, but then I start listening so carefully that I cease to see what I’m doing. Mom is grumbling what do I know and what is wrong with you again and again and Dad is talking over her steadily and laughing in a friendly way without taking his eyes off the game. More words are forming under my hand in an uneasy cursive. My sister, age nine, stomps through the scene and out the back door, slamming it for all of us. Mom and Dad’s voices rise but are cut off at a strange cracking sound. We all turn to the picture window to see my sister smashing walnut-sized white decorative rocks from the neighbor’s garden with a hammer on the concrete patio. She pulls the hammer as far above her shoulder as she can and brings it down on a rock, splitting it into dust and flying shards. Dad looks back to the TV. Mom rushes out the door and now my sister hugs the weapon to her chest; Mom appears and rips it away from her. I am recording this so carefully that I don’t see it while it is happening.

Where am I when I am listening and watching so carefully?

At the dinner table I am watching my parents’ simmering volley crescendo from pissy fork drops to plate slams to stomps off and squeals away, my sister biting into the cruel talk just to feel included, me just watching as if on the living room side of a television screen: I could see them but they could definitely not see me. I squashed my wet veggies around on my plate, eyes fixed to their drama, exactly as I’d do in front of Scooby Doo or G.I. Joe. I could sleep, I could squirm off, I could hum, dance, or even talk, safe in their blind spot. I could write, I discovered, and no one could hear me.

One survival technique is to get small. When resources are thin and you must stay where you are, as you must as a child, it helps to stay invisible. This family, collected together occasionally in one house, or more often, in various split combinations of children and adults, netted around me like a loose constellation of problems. On my small ground, as if in another country, I was not a problem. I kept quiet, was good and smart and secret and neat, reading and playing alone, catching bugs, collecting rocks, reading and drawing. And I wanted to become even less, a nothing, because I thought they could all at least have that, this one non-problem in the house, to not yell and not cry, to sweep the kitchen and pick up the thrown things and secretly restore order to whole fought-apart rooms and even to sometimes sing softly, happily, maybe for them to hear. I have kept quiet about all this my whole life.

4

Suddenly one day, like a membrane breached: before, Dad was like all other dads and then not. We sat together in a booth at the Big Boy, the winter-black windows reflecting back a weak pair of us, and I idly asked him what recording studios are like and how they work. I was something like eleven, and I had a cloudy notion that it would be exciting and romantic to work in a recording studio, to help create music but not have to play it. He fluttered his eyes upward, as he often did, and answered without hesitation.

He told me about the equipment, and how bands work with producers, how much money sound engineers make, and what their schedules are like. Details, I started to realize, he could not possibly know. Some giant drum began turning behind my eyes.

I could see he was lying. Something changed around his eyes when he spoke, a kind of haze or color shift, and I could always see it from then on.

As he talked, I felt my belief, something I didn’t know was there until I felt it moving, turn away from him until it was gone, and I was just alone, nodding and smiling. But what a marvel to watch him construct bullshit and to finally see it right. He stopped in the middle of a sentence about groupies.

“Finish your chicken,” he said. I stared at him in silence. His face went blank as a wall.

“I’m full thank you,” I said cheerily, trying to hide my thoughts. I watched the new man in his seat. He withdrew money from his wallet for the bill and watched me back. A barrier of pressure between us he would not cross. He’d lost his mark.

5

From under the bed I pull a plastic bin stuffed with notebooks: thousands of pages of writings, days I set down, starting at age eight. I would give anything to see the artifacts again—the actual days I spent with my family—to turn them over in my hands and catalogue their facts with my grown-up faculties. Who doesn’t wish for this? Now those days exist only in this bin of paper versions, each entry skewed in the grasp of a child, absent of context.

The earliest diary is a black-and-white, static-print composition book. The beginning pages are covered in unicorn and rainbow drawings and sketches of bulbous fancy dresses done in crayon and neon-colored pencils. Then some pages stuck in from school writing activities:

Shoes

By Molly

I just got new sandals.

I have grils black high tops to.

My Shoes are always filled with sand.

Other pages about puddles or balloons or Halloween are happy and fine, with plenty of exclamation points and normal childhood engagement with the world. I read “Shoes” over and over. I leave it next to me while I pile the rest of the diaries onto my bed, searching farther. My eyes get caught on the By Molly a few times until I let myself look at the page again. I have been ignoring myself for so long. All of this personhood here, catalogued in plodding blindness and thrown into a bin and hidden. My Shoes are always filled with sand.

I open the composition book again. The first real entry is dated June 25, 1988.

Today nothing is pland. Well I don’t kno. Yesderday I played where the tree got cut down and mom said its a hot summer. I put food out for farries but it is still here today. My sister got dropped off at dinner. She was mad and didnt talk. She cried and turned red and then stromed outside and said she running away. I ate her plate tuna casaroll. We looked for her she was under the pine tree. She didn’t talk. She only just scramed I hate you. Today Im don’t care what she does.

Tiny squares of Swiss cheese and mini marshmallows for dessert, I remember that, putting food out for fairies. I don’t remember the rest of this. At that point I was old enough to see that our survival was threadbare compared to the other kids I knew, which explains the remarks about stealing my sister’s portion of tuna casserole as soon as she stromed away, and the feeling of almost sickening marvel at new shoes in the other entry, which seemed too nice for me. And I remember my sister grating against Mom and me, the feeling of grating in my chest when we were together, that exact verb, grating. I kept turning away and away, today Im don’t care, today Im don’t care, but the grating stayed.

Michigan did see a hot summer in 1988. And it was the last year we’d all live together as a family: Mom, Dad, sister, me. I look at the bin of diaries again, feeling overwhelmed. There’s so much to learn there, so much I don’t know about my family.

I didn’t know Dad gambled. Sports betting mostly, on football, baseball, or college basketball, point spreads, totals, any angle. Bookies, calls to Vegas, two or three TVs at once.

I want to say plainly everything I didn’t know. I have a little of it now, and I want to hold it up and out. I can’t help but hold it up and out.

I knew there were little paper slips and crazy phone calls and intense screaming about sports games—more intense than seemed appropriate—but it only added up to a private tension orbiting around him, buffeting us away. In the dark, I grew up.

The last entry in the black-and-white composition book from 1988 says:

No one home. Today I went

It ends there.

6

Sports betting is so different from card games or other gambling because the player doesn’t actually play the game he’s betting on. His “game” is in the analysis of its information—knowing which players might secretly be hurt or sick, which refs favor which teams, the particular mood of one stadium over another, the specific combination of one pitcher with a certain kind of weather—and the synthesis of hunches, superstitions, wishes, and loyalties. Beyond that, there are the odds the bookies are offering, which reflect what everyone else is predicting, also a factor to weigh for or against. A perfect game for someone who thinks he’s smarter than everyone else.

Before Detroit built big casinos downtown there was Windsor Casino right across the border, so there was always blackjack, too. But nobody knows much else about this—my mom, my sister, his coworkers, his brothers and sisters—no one saw his gambling, no one was invited to come along, to share strategies, or even to wish him luck. It was totally private. Mom’s experience of his gambling came to her only in cold losses: an empty savings account, the car suddenly gone, bills and debts, threatening phone calls. Sometimes he’d come home with broken ribs, or a broken nose not to be discussed. The rare big win must have been wasted immediately in private, usually on more gambling, or something showy and useless like a new watch for himself. Or, of course, his debts, eternal debts.

Outcomes shake out fast in gambling. In real life, big risks take years to reveal themselves, and the pressure of choosing a career, a partner, a home, a family, a whole identity, might overwhelm an impatient man, one who values his own control, not fate’s. He will either want all the options out of a confused greed—hoarding overlapping partners, shallow hobbies, new alternate selves—or he will refuse them all, risking nothing. And really, the first option is the second option. Keeping a few girlfriends or wives around effectively dismisses a true relationship with any one of them. Being a good, hardworking dad and a criminal at the same time is a way of choosing neither.

Besides, an addict is already faithfully committed to something he prioritizes above all else. Gambling addiction, particularly, is easy to start; it usually requires no elaborate or illegal activities, no troublesome ingestion of substances, and programs the body using its own chemicals: adrenaline, endorphins, spikes of joy. Only once did I see Dad’s face after a night of gambling. I was eight. It was early Sunday morning, before Mom or my sister were awake. I was belly down on the carpet with a small arrangement of Legos, singing to myself, light still gray in the living room. The front door unlocked and opened and I looked, petrified with fear. Dad, obscure in silhouette, but shining somehow, his hair wet, face wet. Stony expression: eyes set steady, mouth drawn in. His shirt hung heavy on him. I stared from the floor, silent. He didn’t see me. He turned, still blank, and disappeared down the hall. A dark V of sweat running down the back of his shirt. Quietly I turned back to my Lego arrangement, looking at it, but not seeing, quiet.

What did I know about gambling? Even as I grew older, I avoided sports, avoided casinos and card games, avoided even the lottery. As an adult I wasn’t equipped to understand him, having no understanding of gambling.

At first I thought gambling was about chance, just the possibility to make something out of nothing, to multiply money just through pure cleverness. He’d like that: something from nothing.

And that is the first charm. But I know now that gambling is about certainty, not chance. Outcomes, whether win or lose, are certain, immediate, and clear. In other words, there will be a result to any one bet, a point in time when this risk will be unequivocally resolved and the skill and foresight of the gambler can be perfectly measured. A shot of adrenaline will issue into the bloodstream, win or lose. It’s not messy, not indefinite or uncontrollable, like love or people, things Dad labored to control. The space of gambling absorbs its players away from uncertainty, the unknown: how the world works.

7

My dad was born August 19, 1945, in a refugee camp set up for the survivors just liberated from Nazi concentration camps. This is how he first lived: being carried by his mother, in secret, while she worked silently as a slave for the Nazis in Kempten.

The previous year his mother and father and five siblings were moved out of their home in Szwajcaria, Poland, by the Nazis and forced to board a train. My Aunt Helena, a few years older than my dad, told me she remembers the train. She recalls their mom, Stanislawa, hopping off the train when it stopped to hunt for wood to start a cooking fire. Stanislawa’s parents and three of her siblings had died a few years before in Siberia, having been shipped there to cut trees for the Russian supply. “The trees would shatter if they hit the ground because it was so cold. No one had enough clothes or food, so most people died there,” Aunt Helena told me in a recent letter replying to my inquiries about our family history. She has memories of their life during the war, “but they don’t seem real,” she told me. She remembers the mood of the train: the animal-like panic any time the train stopped, the worry of the adults, and her worry when her mother would disappear. They were taken to the Dachau concentration camp, where my grandfather was beaten and interrogated daily because they suspected him of being a partisan, like his brothers.

My dad’s dad was separated from the family. The rest of them lived and worked together, hoping he’d be returned.

After a few months all of them were transferred to a subcamp in Kempten, Germany, where they worked the farm that fed the captives. This is where my grandmother became pregnant with my father. She hid her pregnancy because she was afraid she’d be forced to abort it, so she worked like everyone else and hid her body. Everyone had to work to be fed, even the children and the sick. My aunt remembers little about this time, and won’t say much. “There were horrors every day,” she says. I don’t press her. The war was over in April and my dad was born in August.

After the war they were moved to a refugee camp while trying to find a way out of Germany. My grandfather felt strongly that they should move to Australia, since he liked the idea of working a homestead and living freely, as a farmer. But a few months before they were to leave, he died, and Australia no longer welcomed a widow with five children. They were offered a passage to America through a Catholic sponsorship program, and they took it. My dad’s first memories were of this ship: troop transport, cold and gray all around, the sea and metal smell.

They arrived at Ellis Island on December 4, 1951, and Dad’s name was changed from Jozef to Joseph. They traveled by train to Detroit. Their sponsor took them to St. Albertus Church, on the corner of St. Aubin and Canfield Streets, on the other side of I-75 from Wayne State University, an area that used to be called Poletown. They lived on the top floor of the adjacent school, built in 1916, until my grandma found work in the cafeteria of the Detroit News and rented an apartment for them. Now St. Albertus, no longer a parish as of 1990, stands among abandoned buildings and urban prairie.

Inspired by the family history illuminated by my aunt, I emailed Dad asking him to tell me about his life growing up in Detroit. I had no idea where he was born, and I had no inkling of the incredible ordeal his family shuffled through. He’d never told me any of this. Was it shame? Would he even reply? Quickly he wrote back to say he’d write me a letter, two letters in fact, since he was sure he wouldn’t be able to fit it all in one envelope. I waited a month, two months: it wasn’t like him. I thought maybe he was sick or worse. Eventually it came—he’d gotten in trouble at his job, he said, for disobeying an order, and had been in solitary confinement for the past few weeks.

The first letter, written on yellow lined paper, was long and cheery. I was suspicious. I’ve always been both suspicious and suspicious of my suspicion when listening to Dad. What if it wasn’t all lies this time? What if he let me in—would I be strong enough to follow? But mostly I knew it would be what it was: an innocuous and slightly heroic vision of himself, his official story, nothing deeper.

He described the neighborhood, a tight-knit, mini Eastern Europe: small blocks of varied ethnicities grouped around their churches, family-owned shops, and split homes. They were terribly poor, living off charity and the small salary that his mom made washing dishes in the cafeteria of the Detroit News office downtown. He described her as “superstitiously religious.” Every day before school he attended service at St. Albertus, and also on Sundays, leaving only Saturdays without church. His whole world was built on the church—his family, his neighborhood, his education, his citizenship in this country. When they did move out of the school, they lived only a few blocks away. He said he was almost never too far away to hear the church bells chime every fifteen minutes. He said he loved the church. The overwhelming detail of the stained glass, the painted ceiling, the enormous organ, the grand, formal rituals—all of it must have been a steady comfort to him, to all of them, in a new country.

It was nice to hear, I must admit, and it made sense. I didn’t much see the impression of the Catholic Church on him, but for his love of luxury. It contrasted with the moral tone of my upbringing by Mom: the blue-collar, midwestern work ethic that identifies laziness, indulgence, and shortcuts as serious sins, having nothing in common with Catholicism besides guilt as a motivational technique. Luxury disgusted me. It all seemed false, however real the materials, however deep the ostentation, or honest the funding—it was all predicated on the notion that money itself meant something big, was glorious. I know if I had grown up as poor as my dad I would most likely see this differently.

Dad’s mom eventually remarried, to an older Lithuanian man whose money helped the family enormously. They moved into a real house, out of the fleabag apartments they’d been moving through, and he suddenly had a stepdad. He would only describe his stepdad as “crabby.” His brothers fought with him regularly, and so he kept his distance. In one letter he tells me his stepdad carved for him a toy wooden rifle—the one and only present he ever gave him—and how much he loved it. My dad devoted one whole letter to describing him, the houses they lived in, and which of his siblings moved out when. The second letter is colder and hesitant. Dad was the last to leave home. I can see him there, with his mother to whom he could hardly relate, and his distant stepfather, a non-dad, for whom there was no real role in his life. He turned inward. I know how that works. Perhaps he felt abandoned or lonely.

By the time he was leaving elementary school his neighborhood started to change too. As the Polish immigrants moved to Hamtramck and other white neighbors moved to the suburbs, black folks replaced them—people whom my father had, until this point, never met. “With them,” he wrote, “came crime and drugs. It was demoralizing, to see these strange black people that I previously saw at a distance now living next door to us.” His childhood world, as small and culturally monolithic as most childhood worlds, was cracking open. The Polish family on the corner moved out and the property became a post for drug dealers in just a few months. The family-owned businesses he grew up with closed or moved. Tensions boiled. Newly established black-owned businesses were torched. Vigilante “patrols” were established to keep one group away from another group’s street. White immigrant families abandoned entire blocks together, chasing hopes for reestablishing homogenous neighborhoods elsewhere. This is the story all over Detroit throughout the fifties and sixties, White Flight, how abandonment began to build a “white noose” around the city. In his letter he says most people do not have a “good reason” to dislike black people, but he does. I am ashamed by this and I wonder what potential warmth was cut from his personality in his turn toward hatred of his neighbors.

He stayed in Detroit until he left for Vietnam in the midseventies. When he returned, he moved to a flat just a few blocks away from St. Albertus with his first wife and their daughter, my half-sister. And every letter he has ever written to me about his life story ends there. Perhaps this is just practical—he thinks I know the rest of the story. But, this is important. This part of his life—everything before he met my mom—this is the part he can present as wholesome. He was innocent then, not a criminal yet—or at least, could say he was innocent then. All the letters end there.

8

I know my dad feels a hole where his father should be. Everyone in his family knew his father except him. His first letter to me starts with “You probably know that if my father had lived, my life would have turned out much differently.” On the surface I know he means they would have moved to Australia. But there is more to it. I don’t think he really knows how well I understand this.

I’ve seen a few photos of him when he was a child. One I remember hanging in a frame with other photos—he was a child and someone was holding him; a man, possibly his stepfather, was standing with his mother and siblings in front of a house and landscape. He had a serious face but a tree trunk had aligned just perfectly behind him so it looked like it was growing straight out of his head. My sister and I used to look at this and laugh about it. I’d look closely at this small black-and-white photo, sad and stiff, but laugh at it.

One photo I own—it is a new and glossy reprint of a photo and I’m not sure how I came to have it. Probably I stole it from a photo album at some point. Dad’s family is all clustered around his father’s fresh grave. They must be in Germany, at the camp where Dad was born. His oldest sister is standing, looking down at the grave, next to a wooden cross at the head of the grave, a small photo of his father’s face nailed to the center. His two brothers kneel at the foot of the grave, looking with sad, small faces at whoever was taking the photo. Worn faces, especially for children. His other sister, next to them, is looking into the camera, brows knitted, hands pressed in prayer. She looks serious and intelligent. And then, in the middle, his mother, kneeling in black, holding Dad. His mother looks directly into the camera, chin down, mouth open a little as if she was just saying something. She is pretty and tough, with high, wide cheekbones like mine. Dad is just a baby, wrapped all in black. He is looking somewhere else entirely. His face is neutral. Pudgy cheeks bulging downward. He is the only one there who doesn’t understand.

The background is just gray, vague hills. Ghostly gray blankness. I keep the photo facedown in a folder with the letters he has written to me. It confronts me. Who would have taken this photo of a family in their most private and serious moment of grief, not posing but mourning next to their father’s grave? And is this what I am doing now in writing about my family?

My dad’s father’s name was Kazimierz and he was a farmer, famous for breaking horses in the river Strypa. His parents were killed in Poland in 1941. Before he died he received news that his four brothers had been executed for treason. He died from a heart attack on his thirty-sixth birthday in March, 1948, when my dad was two years old.

Aren’t we together on this, Dad, together on missing our dads, and what it has done to you and me? You left an unknowable self behind, with us, your cover story, your dupes, and I kept following. And I’m still following, somehow more than ever, in love with this trouble, this difficult family, in love with my troubled mom and sister and you too, maybe most of all you, the unknowable one.

9

From the window of the cab our beachfront hotel approached like a dream, as wrong as a dream, and I felt sickly overwhelmed with the luxury of the fantastic palm trees and clean arched doorways. This could not be right. I hung my mouth open a while in joy and suspicion as we left the cab, for him to see. He made a goofy roundabout pointing sweep to the door and said “Lezz go,” goofily, like he did. Thinking about it now, the hotel was probably nothing special, maybe even cheap, but I couldn’t have known.

This was the longest period of time we spent alone together as father and daughter. I was nine or ten and he’d brought me to Cancun, an unlikely place to take a child on a summer vacation for no particular reason. He had a habit of taking vacations with just me or just my sister, never both of us together, and never with Mom, even when they were married. I imagine we never went anywhere all together as a family because Mom and Dad usually hated each other, but I didn’t get why my sister and I couldn’t go somewhere together. Now, reasoning it out, I run through a spectrum of guesses: on the practical end, there is cost and scheduling logistics, and on the other end, the darker end, there is purposeful isolation.

During the day he would leave me. I’d wake up and find a key and a note atop some money: Have fun! Wear sunscreen! I’d put on my nubby yellow bathing suit and take myself to the beach or the small intensely chlorinated pool and try hard to have a fun vacation as instructed.

What was he doing? Was there somewhere nearby to gamble? There must have been. Or was there a woman he met? He’d return in the evening and take me to eat somewhere nearby. He always ordered a hamburger and a Coke for me without looking at the menu, even though I hated hamburgers and Coke. Mom wouldn’t let me drink soda, and it seemed important to him to break her rules.

“Hahmm-borrr-gaysa,” he’d say to the waiter, childishly drawing out the words and gesturing coarsely as if the waiter were near-blind and deaf, “and Coca-Colé!” he’d finish, pronouncing the “cola” part with a silly “Olé!” paired with an insulting bottle-drinking mime. He was condescending to waiters everywhere like big shots often are, but especially here. “This is the only word you need to know,” he told me from across the dark booth. “Hamburguesa.” I tamped down my disgust with obliging laughs, since clearly this show was for me. I did not recognize his gold chain and ring. I watched him carefully, waiting for a time when we’d say real things to each other.

I didn’t tell him that I liked my days there, on the beach, alone like a grown-up. But anxious. I knew the untethered feeling I liked was not right for me yet. If he asked, I would have told him about my days lying on a blue towel, just lying there for hours, burning pink in the sun, listening while two Mexican teenage girls talked next to me, oblivious to my eavesdropping, alternating between Spanish and English. They talked about how wonderful it would be to be born a gringa, the kind of house they’d live in, what their boyfriends would look like, and how their daddies would spoil them with cars and clothes and fantastic birthday parties.

One of the days he didn’t leave, he waited for me to wake up and took me to a Mayan ruin site. Before the tour we foreigners drew in automatically to giant steep steps of a pyramid and began to climb. It was so soaking hot, and I felt so young and small. The other tourists seemed to have such trouble climbing. I bounded up the old blocks, turning to the wide mush of treetops below and smiling. Dad down below. I waved to him but he wasn’t looking.

We were herded up for the tour and kids my age and even older were already whining. I couldn’t imagine complaining even half as much as my peers did. It frightened me, the way they said what they wanted. Hungry and tired and thirsty and bored and ugh, Dad, can we go? At the edge of the cenote nearby a tour guide described how the Mayans would sacrifice young women here by tossing them in; “girls about your age,” he said and pointed at me. The group of tourists around us chuckled uncomfortably but I straightened up.

I rested on a boulder carved into a snake’s head, wearing the only hat I owned as a child, a black-and-neon tropical-print baseball hat I am certain came from a Wendy’s Kids’ Meal. I feel there was a photograph taken of this that I remember seeing, and I wonder if it still exists somewhere. I remember resting on the snake’s head and I remember the photograph of myself resting on it equally. I liked this day, seeing these things that seemed so important, Dad mostly hanging back in the wet shade of the jungle edge, not climbing things. He had brought me here and I loved it. I felt the secret urge children have to become lost and stay overnight somewhere good, like a museum or mall, as a way of being there privately, directly. I circled the pyramid hoping to find a cave where I could curl up, so I could sleep and stay inside this old magic, like a good sacrifice, just right for something serious. But it was hot and we had to go. Dad seemed tired, suspicious of it all, not especially interested in learning too much from the guide or in looking too hard at the ruins. I was happy, though, and he was pleased with that. He seemed to want to let me have my happiness without necessarily sharing in it or talking about it. Perhaps it’s easy to dismiss children’s happinesses because they seem so uninformed.

On the way back, our tour van had to stop for gas. Children my age but much skinnier came to the windows with their hands out, pleading and keeping steady eye contact. Some tourists in the van gave them coins. The kids who received coins immediately pocketed them and outstretched their hands again, empty. I looked at my dad. He laughed dismissively. “They’re just bums. They can work like the rest of us.”