Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

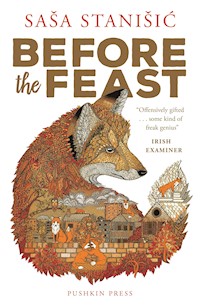

It's the night before the Feast in the village of Fürstenfelde (population: declining), but not everyone is asleep. The local artist, wearing an evening dress and gumboots, goes down to the lake under cover of darkness. The village archivist is kept awake by ancient tales that threaten to take on a life of their own. A retired lieutenant-colonel weighs his pistol, and his future, in his hand. And eighteen-year-old Anna, namesake of the Feast, prepares to take her place in tomorrow's drinking and dancing, eating and burning.On this night of misdeeds and mischief, they are joined by a dead ferryman, a hapless bellringer, a cigarette machine, two robbers in football shirts and a vixen on the hunt - as their fates collide in the most unexpected ways.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 373

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Winner of the Leipzig Book Fair Prize

Longlisted for the German Book Prize

Winner of the HR2 Audiobook Prize

Winner of the Alfred Döblin Prize

Winner of the Hohenemser Literature Prize

SAŠA STANIŠIĆ

BEFORETHE FEAST

Translated from the German by Anthea Bell

PUSHKIN PRESS LONDON

For Katja

For billions of years since the outset of time

Every single one of your ancestors has survived

Every single person on your mum and dad’s side

Successfully looked after and passed on to you life.

What are the chances of that like?

The Streets, “On the Edge of a Cliff”

Contents

I

WE ARE SAD. WE DON’T HAVE A FERRYMAN ANY MORE. THE ferryman is dead. Two lakes, no ferryman. You can’t get to the islands now unless you have a boat. Or unless you are a boat. You could swim. But just try swimming when the chunks of ice are clinking in the waves like a set of wind chimes with a thousand little cylinders.

In theory, you can walk round the lake on foot, keeping to the bank. However, we’ve neglected the path. The ground is marshy and the landing stages are crumbling and in poor shape; the bushes have spread, they stand in your way, chest-high.

Nature takes back its own. Or that’s what they’d say in other places. We don’t say so, because it’s nonsense. Nature is not logical. You can’t rely on Nature. And if you can’t rely on something you’d better not build fine phrases out of it.

Someone has dumped half his household goods on the bank below the ruins of what was once Schielke’s farmhouse, where the lake laps lovingly against the road. There’s a fridge stuck in the muddy ground, with a can of tuna still in it. The ferryman told us that, and said how angry he had been. Not because of the rubbish in general but because of the tuna in particular.

Now the ferryman is dead, and we don’t know who’s going to tell us what the banks of the lake are getting up to. Who but a ferryman says things like, “Where the lake laps lovingly against the road”, and “It was tuna from the distant seas of Norway” so beautifully? Only ferrymen say such things.

We haven’t thought up any more good turns of phrase since the fall of the Berlin Wall. The ferryman was good at telling stories.

But don’t think that at this moment of our weakness we ask the Deep Lake, which is even deeper now, without the ferryman, how it’s doing. Or ask the Great Lake, the one that drowned the ferryman, what its reasons were.

No one saw the ferryman drown. It’s better that way. Why would you want to see a person drowning? It’s not a pretty sight. He must have gone out in the evening when there was mist over the water. In the dim light of dawn a boat was drifting on the lake, empty and useless, like saying goodbye when there’s no one to say it to.

Divers came. Frau Schwermuth made coffee for them, they drank the coffee and looked at the lake, then they climbed down into the lake and fished out the ferryman. Tall men, fair-haired and taciturn, using verbs only in the imperative, brought the ferryman up. Standing on the bank in their close-fitting diving suits, black and upright as exclamation marks. Eating vegetarian bread rolls with water dripping off them.

The ferryman was buried, and the bell-ringer missed his big moment; the bell rang an hour and a half later, when everyone was already eating funeral cake in the Platform One café. The bell-ringer can hardly climb the stairs without help. At a quarter past twelve the other day he rang the bell eighteen times, dislocating his shoulder in the process. We do have an automated bell-ringing system and Johann the apprentice, but the bell-ringer doesn’t particularly like either of them.

More people die than are born. We hear the old folk as they grow lonely and the young as they fail to make any plans. Or make plans to go away. In spring we lost the Number 419 bus. People say, give it another generation or so, and things won’t last here any longer. We believe they will. Somehow or other they always have. We’ve survived pestilence and war, epidemics and famine, life and death. Somehow or other things will go on.

Only now the ferryman is dead. Who will the drinkers turn to when Ulli has sent them away at closing time? Who’s going to fix paperchase treasure hunts for visitors from the Greater Berlin area, in fact fix them so well that no treasure is ever found, and the kids cry quietly on the ferry afterwards and their mothers complain politely to the ferryman, while the fathers are left wondering, days later, where they went wrong? Those are mainly fathers from the new Federal German provinces, feeling that their virility has been questioned, and once on land again they eat an apple, ride towards the Baltic Sea on their disillusioned bicycles and never come back. Who’s going to do all that?

The ferryman is dead, and the other dead people are surprised: what’s a ferryman doing underground? He ought to have stayed in the lake as a ferryman should.

No one says: I’m the new ferryman. The few who understand that we really, really need a new ferryman don’t know how to ferry a boat. Or how to console the waters of the lakes. Or they’re too old. Others act as if we never had a ferryman at all. A third kind say: the ferryman is dead, long live the boat-hire business.

The ferryman is dead, and no one knows why.

We are sad. We don’t have a ferryman any more. And the lakes are wild and dark again, watching, and observing what goes on.

THE FUEL STATION HAS CLOSED, SO YOU HAVE TO GO TO Woldegk to fill up. Since then, on average people have been driving round the village in circles less and straight ahead to Woldegk more, reciting Theodor Fontane if they happen to know his works by heart. On average it’s the young, not the old, who miss the fuel station. And not just because of filling up. Because of KitKats, and beer to take away, and Unforgiving, Orange Inferno flavour, the energy drink that takes East German fuel stations by storm, with 32 mg of caffeine per 100 ml.

Lada, who is known as Lada because at the age of thirteen he drove his grandfather’s Lada to Denmark, has parked his Golf in the Deep Lake for the third time in three months. Is that to do with the absence of a fuel station? No, it’s to do with Lada. And it’s to do with the track along the bank, which in theory is highly suitable for a speed of 200 km/h here.

The lake gurgled. At first Johann and silent Suzi, up on the bank, thought it was funny, then they thought it wasn’t so funny after all. A minute passed. Johann took off his headband and plunged in, and he’s the worst swimmer of the three of them. The youngest, too. A boy among men. All for nothing; Lada came up of his own accord, with his cigarette still between his lips. Then he had to lend a hand with rescuing Johann.

Fürstenfelde. Population: somewhere in the odd numbers. Our seasons: spring, summer, autumn, winter. Summer is clearly in the lead. The weather of our summers will bear comparison with the Mediterranean. Instead of the Mediterranean we have the lakes. Spring is not a good time for allergy sufferers or for Frau Schwermuth of the Homeland House, who gets depressed in spring. Autumn is divided into early autumn and late autumn. Autumn here is a season for tourists who like agricultural machinery. Fathers from the city bring their sons to gawp at the machinery by night. The enthusiastic sons are shocked rigid by the sight of those gigantic wheels and reflectors, and the racket the agricultural machinery kicks up. The story of winter in a village with two lakes is always a story that begins when the lakes freeze and ends when the ice melts.

“What are you going to do about your old banger?” Johann asked Lada, and Lada, who is no novice at the art of fishing cars out of the lake and getting them back into running order, said, “I’ll fetch it one of these days.”

Silent Suzi cast out his fishing line again. He had barely paused for Lada’s mishap. Suzi loves angling. If you’re born mute, you’re kind of predestined to be an angler. Although what does it mean, mute? Saying his larynx doesn’t work would be politically correct.

Johann gently tapped out a rhythm on his thigh. He has his bell-ringing exam tomorrow, and he’s going to play a little melody of his own composed specially for the Feast. It’s to be performed by striking the bells instead of making them swing. Lada and Suzi don’t know anything about it. It’s better that way or they’ll make fun of him.

They stripped to their underpants, Johann and Lada, so that their clothes could dry, Suzi out of solidarity. Lada’s flawlessly muscular build, Suzi’s flawlessly muscular build, Johann’s skinny ribs. Suzi combs his hair back, he always has a comb with him, a custom now verging on extinction. A dragon’s tail on his forehead, the mighty dragon’s body round the back of Suzi’s neck, the dragon’s head on his shoulder-blade, breathing fire. Suzi is as handsome as the stars of Italian films in the 1950s. Suzi’s mother is always watching those films and shedding tears.

Grasshoppers. Swallows. Wasps. Tired, all of them, very tired.

Autumn is on the way.

Today was the last hot day of the year. The last day when you could comfortably lie on the grass in your underpants, with beetles climbing all over you as if you were a natural obstacle in the terminal moraine landscape, which in a way you are. If you come from here, you know that sort of thing: it’s the last hot day. Not because of the swallows or the weather app. You know it because you’ve stripped to your underwear and you’re lying down, and if you are a girl you’ve burrowed your toes into the sand, if you’re not a girl you haven’t done anything with your toes, you’re just lying down. And, lying like that, you looked up at the sky, and it was perfectly clear. Today—the last hot day. If by some miracle there should be another one after all, it wouldn’t mean anything. Today was the last.

Lada and Johann watched Suzi and gave him tips, because he wasn’t catching anything. Try under the ash tree, it’s too hot for the fish here, that kind of thing. Suzi put the rod between his legs and gestured wildly. Lada understands Suzi’s language quite well, or rather, he doesn’t know it all that well but he has known silent Suzi for ever.

“We have all the time in the world,” he translated for Johann’s benefit. Johann looked at him enquiringly. Lada shrugged his shoulders and spat into the lake. Anna came along the lakeside path on her bike. Wearing a dress with what they call spaghetti straps or something like that. Johann spontaneously waved. He’s a boy, after all. Anna looked straight ahead.

“What are you waving for?” Lada punched Johann’s shoulder. “Let me show you how it’s done.” An excursion boat was chugging over the lake. Lada whistled shrilly. The tourists on board were moving under the shelter of their roof. Lada waved, the tourists waved back. The tourists took photos. Then Lada showed them his middle finger.

“That doesn’t count, they’re tourists waving. They’ll wave no matter what,” said Johann.

Lada punched him again. There’s a wolf baring its teeth on Lada’s shoulder. The wording on Lada’s back says The Legend. The lettering is almost the same as in the ad for the energy drink.

“What are you staring at?”

“I’m going to get a tattoo as well.”

“Hear that, Suzi? This wanker’s going to get a tattoo. Fabulous.”

One thing Johann has learnt from knowing Lada is not to lose his nerve. To stick to his point. Letting people provoke you shows weakness. “Does that mean anything?” he asked. Suzi has a wolf on his calf as well.

Lada looked him in the eye. Spat sideways. “The wolves are coming back.” He spoke very slowly. “Germany will be wolf country again. Wolves from Poland and Russia, they can cover thousands of kilometres. Wonderful animals. Hunters. Say: wolf-pack.”

“Wolf-pack.”

“Wicked, right? Such power in that one word! Suzi and I support the wolf.” Lada grabbed Johann by the back of the neck. “This is just between ourselves, okay? We’ve brought wolves. From Lusatia. Because once there were wolves here too. Ask your mother. In the Zerveliner Heide, near the rocket base? We set them free.”

Stay cool. Ask more questions. Sometimes Lada just goes rabbiting on like that to scare Johann. Suzi has turned round, listening intently. Johann cleared his throat.

“How many?”

“Very funny. I thought you’d ask how. Four. Two young wolves, two adults. Listen, you: it’s no joke. Keep your mouth shut, understand?”

“Sure.”

“Good.”

Suzi had a fish on his hook. It put up a bit of resistance. A small carp. Suzi threw it back in the water again.

Lada got up. “Off we go to Ulli’s, you guys. Suzi will stand us a drink.” And that’s what they did, because Lada is someone who keeps his word.

A CARP CAN FEEL ENVY FOR FOOD. WHEN THE OTHER FISH come to feed, it joins in. But from autumn onwards, as the water temperature drops, it needs less and less nourishment.

Male hornets copulate with the young queens and then promptly die. The young queens settle down to wait for spring under moss, in rotten wood, in the dragonfly’s nightmares.

In the Kiecker Forest, the old woods, the woodpecker chisels out the milliseconds of our mortality.

For autumn is here.

The wolf-pack is awake.

IT WAS EXACTLY A YEAR AGO, ON THE DAY BEFORE THE LAST Feast, that Ulli cleared out his garage, put in some seating and five tables and a stove, hung a red and yellow tulle curtain over the only window and nailed a calendar with pictures of Polish girls leaning on motorbikes to the wall, partly for the ironic effect, partly for the aesthetics of it. A Sterni beer costs you eighty cents, a Stieri ninety, a beer with cherry juice is one euro fifty, and you can watch football at the weekend. The guys think well of Ulli because of all this, even if they don’t say so.

We drink in Ulli’s garage because you don’t get a place to sit and tell tall tales and a fridge all together like that anywhere else, which makes it a good spot for guys to be at ease with each other over a drink, but at the same time not too much at ease. Nowhere else, unless you’re at home, do you get a roof over your head, and Pils, and Bundesliga on Sky, and smoking and company.

We do have a restaurant too, Platform One, and it’s not at all bad. Still, you don’t want to get drunk in Platform One. You want to have dinner, maybe celebrate an anniversary, but try to get well tanked up while plastic flowers and tourists who come on bicycles are watching you. Now and then Veronika brings real tulips in. Try to get well tanked up while real tulips are watching.

Ulli’s garage has a good smell of engine oil. Motorbike badges and beer ads adorn the door, and there’s a shield with the imperial eagle on it and the words German Empire. It’s a fact that almost no one but men come from the new prefabricated buildings. Sometimes there’s trouble, nothing too bad. Nothing really nasty. Sometimes you can’t make out what you’re saying. In retrospect you’re glad of that. Sometimes someone tells a story and everyone listens. This evening, it will be old Imboden telling the story over the last round. Imboden is usually a quiet but fierce drinker. His wife died three years ago, and it was only then that he began coming here. Ulli says he has to catch up after all those years of sobriety.

In the garage, and because of the Feast tomorrow, the talk was about earlier feasts, and how feasts in the old days were better than now. For instance, no one could remember a good, really satisfying brawl among grown men in the last couple of years. They used to be the norm. These days only the young lads fight. “Badly, at that,” said Lada, laughing, but no one else laughed.

So now Imboden stands up to go and take a piss, but before he leaves the room—the garage doesn’t have a toilet, but there’s something like a tree in front of the prefab—he says, “Just a moment. This won’t do.”

For several weeks there’s been a colour photo stuck to the fridge. Ulli’s granddaughter Rike is going through a phase. The picture shows Rike and her grandpa in a little rectangle, which is the garage. When Ulli put up that picture he took the naked Polish girls down. As a result the men called Ulli Gramps for a few days, but then they forgot about it and called him Ulli again.

Everyone can drink at Ulli’s, even drink more than he can take on board. But when a guest can’t lie down without holding on to something, Ulli gives Lada a nod, and Lada escorts or carries that guy out.

Everyone can talk at Ulli’s and say more than anywhere else. But if he goes on talking and saying more, and Ulli has had enough of it, Ulli gives Lada the nod.

You pay less at Ulli’s than anywhere else. But if anyone hasn’t paid in full after a month, then Ulli gives Lada the nod.

Everyone can weep at Ulli’s, out loud at that. But no one does weep at Ulli’s.

Everyone can tell a joke at Ulli’s that we don’t all think is funny. But when a guy means something seriously that we don’t all think is funny, Ulli gives Lada the nod.

Everyone can tell a story about the old days at Ulli’s, and usually the others listen.

Old Imboden came back from having a piss, and Imboden told his story.

THE VIXEN LIES QUIETLY ON DAMP LEAVES, UNDER A BEECH tree on the outskirts of the old forest. From where the forest meets the fields—fields of wheat, barley, rapeseed—she looks at the little group of human houses, standing on such a narrow strip of land between two lakes that you might think human beings, in their unbridled wish to grab the most comfortable possible place as their own, had cut one lake into two, making room right between them for themselves and their young, in a fertile, practical place on two banks at once. Room for the paved roads that they seldom leave, room for the places where they hide their food, their stones and metals, and all the huge quantities of other things that they hoard.

The vixen senses the time when the lakes did not yet exist, and no humans had their game preserves here. She senses ice that the earth had to carry all the way along the horizon. Ice that pushed land on ahead of it, brought stones with it, hollowed out the earth, raised it to form hills that still undulate today, tens of thousands of fox years later. The two lakes rock in the lap of the land, in the breast of the land grow the roots of the ancient forest where the vixen has her earth, a tunnel, not very deep but safe from the badger, with the vixen’s two cubs in it now—or so she hopes—not waiting accusingly outside like last time, when all she brought home was beetles again. The hawk was already circling.

She would smell the earthy honey on the pelts of her cubs among a thousand other aromas, even now, in spite of the false wind, she is sure of its sweetness in the depths of the forest. She is sure of their hunger, too, their stern and constant hunger. One of the cubs came into the world ailing and has already died. The other two are playing skilfully with the beetles and vermin. But rising almost vertically in the air from a stationary position and coming down on a mouse is still too much like play. Their games often make them forget about the prey.

The vixen raises her head. She is scenting the air for humankind. There are none of them close. A warmth that reminds her of wood rises from their buildings. The vixen tastes dead plants there, too; well-nourished dogs and cats; birds gone wrong, and a lot of other things that she can’t easily classify. She is afraid of much of what she senses. She is indifferent to most of it. Then there’s dung, clods of earth, then there’s fermentation and chicken and death.

Chicken!

Behind twisted metal wires in wooden sheds: chicken! The vixen is going to get into those chickens tonight.

Her cubs are staying away from the earth longer and longer. The vixen guesses that tonight’s hunt will be her last for her hungry young. Soon they will be striking out and finding preserves of their own. She would like to bring them something good, something really special when she and they part. Not beetles or worms, not the remains of fruit half-eaten by humans—she will bring them eggs! Nothing has a better aroma than the thin, delicate eggshells, because nothing tastes as good as the gooey, sweet yolks inside those shells.

It is never easy to get inside a henhouse. Even if no dog is guarding it, and the humans are asleep. She isn’t afraid of the fowls’ claws. But carrying eggs is all but impossible. Her previous attempts were failures, if delicious failures. This time she will close her mouth as carefully as she closes it on the cubs in play. This time she won’t take two eggs at once but come back for the second.

A female badger slips out of the wood. The vixen picks up the scents of bracken and fear on her. What is she afraid of? Bats fly past overhead. Taciturn creatures, moving too fast for any joking, fluttering nervously away. On the outskirts of the forest a herd of wild pigs is holding a council of war. They are unpredictable neighbours, easily provoked but considerate. Their scent is good, they smell of swampiness, sulphur, grass and obstinacy. Just now they are deep in discussion, uttering shrill grunts in their edgy language, butting one another, scraping the ground with their hooves.

Their restlessness gets the vixen going. She trots off so as to leave those tricky creatures behind quickly.

The Up Above, roaring, brings thunder. It doesn’t like to see the vixen out and about. It is threatening her. Warning her.

AND HERR SCHRAMM, FORMER LIEUTENANT-COLONEL IN THE National People’s Army, then a forester, now a pensioner and also, because the pension doesn’t go far enough, moonlighting for Von Blankenburg Agricultural Machinery, is watching the sports clips on the Sport 1 channel. Martina (aged nineteen, Czech Republic) is playing billiards. Herr Schramm is a critical man. He has objections to the programme, he doesn’t think Martina plays billiards properly. She sends her shots all over the place. They never go into the pockets, and that bothers Herr Schramm. Martina dances round her cue, and that’s not right: it’s not right for her to dance, it’s not right for her to sit on the table and wiggle the billiard balls with her bottom, it’s not right for her to be playing by herself. Because if you are playing by yourself it should be with the clear intention of sinking the balls in the pockets. The opponent you best like to beat, so Herr Schramm firmly believes, is yourself.

Of course, after every shot Martina has to remove an item of clothing, nothing wrong with that. But she could have done it somewhere else. Sport 1 shouldn’t have made a billiard table available to her, it should have been somewhere Martina knows her way around. Herr Schramm believes that everyone is good at something, and he tries to guess what that something might be in Martina’s case. Clues are thin on the ground: she has full breasts, short fingers, shiny fingernails. Herr Schramm believes in talent, and Herr Schramm likes talent. He likes to watch people exercising their talents: he’s an upright military man with poor posture and an empty pack of nicotine chewing gum.

He doesn’t like to watch Martina. Martina still has her knickers on; they are black with a number 8 in a white circle at the front. Herr Schramm thinks that is witty. But it’s not about her knickers now, it’s about the fact that Martina plays so badly, as if she didn’t even know the rules. And rules are the first thing you teach someone who doesn’t really belong in a place.

Herr Schramm is a man who avoids conversations with strangers, and even with acquaintances prefers to talk about anti-aircraft missiles, bats and the former ski jumper Jens Weissflog, the most talented ski jumper of all time.

He thinks Martina has good calves when she bends low over the table. But when she takes off her knickers, drapes them over her cue, misses the white at her next shot and has to laugh at that into the bargain, Herr Schramm has had enough.

“I ask you!” says Herr Schramm. He switches the TV set off.

In German households, on average, there are more germs on the remote control than on the lavatory seat. Herr Schramm thinks about that “on average”. It’s all relative. Lavatory seats are larger than remote controls.

In his own household, thinks Herr Schramm, there are more disappointments about himself, on average, than about the world. With a sigh, he gets off the sofa and in the same movement pulls up his underpants from round his ankles. The rest of his clothes are in the bathroom. He searches their pockets to see if he has enough change for a packet of cigarettes. He does.

Herr Schramm sits in his Golf for a little while first. A tall, upright man with poor posture, thinking: on average. Martina (aged nineteen, Czech Republic). Bats hang upside down because their legs are too weak. They can’t take a run and then fly away, like a goose, for instance.

His pistol is in the glove compartment.

Much that Herr Schramm regrets today was done of his own accord. Pressure is what Herr Schramm was good at. Standing up to pressure and exerting it.

He drives away. Maybe to the cigarette vending machine, maybe to the abandoned anti-aircraft missile department at number 123 Wegnitz, where he was stationed for seventeen years. A few cigarette ends or a shot in the head, he hasn’t made up his mind yet which.

Maybe Martina has a talent for fingernails. What would that be called?

In Wilfried Schramm’s household there are more reasons against life, on average, than against smoking.

WE ARE GLAD. ANNA IS GOING TO BE BURNT. THE SENTENCE will be carried out at the Feast tomorrow evening. The children are put to bed in the hay with the calves, but they don’t sleep, they peep through the boards at what they’d like to be scared of in their sleep, and when there’s no more boiling and hissing and crying in the flames the baker connects up his fiddle to his portable amplifier and then there’s fiddling, then there’s dancing, predatory fish are grilled until they’re cooked and soft. Anna is going to be burnt, and on such a night many couples find their way to each other, they dance among sparks and stars and security precautions, making sure nothing that doesn’t gain by the flames catches fire.

Autumn is here now. Ravens peck the winter seed corn out of the body of the fields. They come down to settle on scarecrows, they preen their plumage.

There’s still time to pass before the Feast. We have to get through the night, and the final preparations will be made in the morning. The village cooks, the village sprays window cleaner on glass, the village decorates its lamp posts. Our carpenter, who is dead now, spent a long time making sure that the bonfire would stand steady. An interior designer brought in from Berlin has offered his services instead, but if we let him get at it, so the village thought, there’ll be nothing but problems; it’s not just a case of where to put your sofa for a good view, we have to make sure we don’t have another disaster like the one in 1599, when four houses caught fire, and in all the commotion two notorious robbers escaped being burnt to death, so now a scaffolding company from Templin does the job.

The village provides itself with seats. The seating plan is a ticklish subject. Who gets to sit at the beer table in front, near the bonfire? Who has earned the merit of being near the flames? Who defines what merit is this year?

The village cleans its display windows. The village polishes up the rims of wheels. The village takes a shower. The fishermen are after pike today, the bakery is generous with its jam fillings. Many households will prudently lay in a double dose of insulin.

Daughters make up their mothers’ faces, mothers trickle eye-drops in the lower lids of tired fathers’ eyes, fathers can’t find their braces. The hairdresser would make a real killing if we had a hairdresser. Apparently one is supposed to be coming from Woldegk, but how is that to be managed? Will he go round the houses like the doctor on his Thursday visits, or put up his chair and mirror somewhere central? We don’t know.

Frau Reiff has invited guests to her pottery on this Open Day: she serves coffee, honey sandwiches and a talk about making pottery. Her visitors get beer tankards made by the Japanese raku method fired in her kiln, or maybe have a go at firing a vase themselves. Later there will be a band from Stuttgart playing African music. The musicians have already arrived. They keep saying how wonderful the landscape is, as if that were the village’s own doing.

Zieschke the baker will be auctioneer for the sale of Works of Art and Curios again. Last year he did it with his shirt worn loose over his trousers and using a beer bottle as the auctioneer’s gavel. The proceeds go to our Homeland House. We can already guess some of the items to be sold:

Antique globe (including Prussia): reserve price 1 euroSelf-adhesive silicon Secret + bra: reserve price 2 eurosLaundry basket with surprise contents: reserve price 3 eurosLocal Prenzlau calendar for 1938: reserve price 6 eurosPeople’s Police uniform (with cap, worn): reserve price 15 eurosBrand new oil painting by Frau Kranz (painted the night before the Feast): reserve price not knownNon-villagers can also bid in the auction, and they laugh at some of the items on offer, most loudly of all when they are no laughing matter. Or that’s how it sounds, when some of them think they are cleverer than the story; they don’t credit us with irony.

Our Anna Feast. No one really knows what we’re celebrating. It’s not the anniversary of anything, nothing ends or began on exactly that day. St Anne has her own saint’s day sometime in the summer, and the saints aren’t saintly to us any more. Perhaps we’re simply celebrating the existence of the village. Fürstenfelde. And the stories that we tell about it.

Time still has to pass. The village switches off its TV sets, the village plumps up its pillows, tonight hardly anyone in the village makes love. The village goes to bed early. Let us leave the dreaming villagers in peace, and spend time with those who lie awake:

With our lakes that never sleep anyway.

With animals on the prowl. Under cover of darkness, the vixen sets out on a memorable hunt.

With our bells, which will soon be ringing in the festive day. These days, who can boast of still having a bell-ringer, and an apprentice bell-ringer too?

Herr Schramm weighs up his pistol in his hand.

Frau Kranz is awake too. What a pity, when many old ladies are snoring! She is out and about, well equipped for the night: torch, rain cape, she has shouldered her easel and is pulling the trolley with her old leather case behind her. Going through the Woldegk Gate, she takes a good slug from her thermos flask, which has more than just tea in it. Frau Kranz is very well equipped.

And Anna, our Anna. Tomorrow is her last day. She lies in the dark, humming a song, the window is open, a simple tune, the cool night air passes over her brow. In this last year Anna has spent a lot of time alone at Geher’s Farm, surrounded by her family’s dilapidated past: her grandfather’s tools, her mother’s garden, neglected by Anna but popular with the wild pigs, in the garage there is the Škoda, in which the cat has had her umpteenth litter of tabby kittens. There is a fallow field run wild under Anna’s window. And tonight, on such a night as this, there are memories of a house that was once full, and the question of what has ever been good for her in the eighteen years she has spent there. On Monday Lada will come to clear the house out, in spring the people from Berlin will take it over, and Anna, on her own, remarkably indifferent to others of her age, Anna with her school-leaving certificate and her love of ships, Anna who shoots her grandfather’s airgun out of the bathroom window at the wild pigs in the garden, Anna up and about at night, even tonight—come here to us, Anna. Come along the headland of the field to the Kiecker Forest, to the lakes, going all the old ways one last time, that’s the plan, we young people of this village, from the new buildings and the ruins, we are glad. Anna is not alone, Anna is humming a tune, a sweet, childlike melody, we are with her.

The night before the Feast is a strange time. Once it used to be called The Time of Heroes. It’s a fact that we’ve had more victims to mourn than heroes to celebrate, but never mind, it does no harm to dwell on the positive side now and then.

Over there by the ovens? The little girl with the log in her arms? She is the youngest of the girls called heroines. A child of just five years old, in a much-mended smock and a shirt too big for her, with pieces of leather wrapped round her feet. Her brother beside her is fair and slender as a birch tree. Timidly but proudly he throws the log that the little girl hands him into the flames. Their mother is placing flax to dry in one of the ovens, she will bake bread for the Feast in the other. The village is celebrating because war has stopped stealing and devouring, driving everything out and killing it, because harvest has kept the promise of seed time. Things could get exuberant, the bigwig from town isn’t here: Poppo von Blankenburg, coarse, loud-mouthed, observing the law as he sees fit.

The village says prayers daily for a to some extent, for an at least. For the continued existence of the fish. For our own continued existence. The little girl and her brother and the sieve-maker’s two boys, there aren’t any other children here now.

This is the year such-and-such. Frau Schwermuth would know the date for sure. She is our chronicler, our archivist, and wise in herbal lore as well, she can’t sleep either. With a bowl of mini-carrots on her lap, she is watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer, series six, right the way through. The Feast and all the upheaval make considerable demands on her: Frau Schwermuth holds many threads in her hand.

The little girl chases her brother round the ovens. Anna, let’s call her Anna. A little while ago the ovens were moved from the village to outside the walls. The fire had sent sparks flying too often, the sparks in their turn had rekindled fire, and like all newborn things the fire was hungry and wanted to feed, it swallowed up barns and stables, two whole farms—although the Riedershof fire, people say, had nothing to do with the ovens. It was to do with the Devil. The Rieder family were in league with him, and the Devil had simply been taking an instalment of the bargain.

The children’s mother sweeps the glowing embers out of the oven with a damp bundle of twigs and puts a loaf into it, carefully, as if putting a child to bed. She reminds the children to keep watch on both the bread and the flax, it wouldn’t be the first time that someone helped himself to what didn’t belong to him. “Come and get us if you see strangers arriving.”

Let’s leave the picture like that: the girl’s brother is combing Anna’s fair hair with his fingers. The little girl stands closer to the oven, holding out the palms of her hands to the stove flap. Their mother sets off along the path back to the village, humming a tune.

Anna, our Anna, has a similar tune on her lips. She shivers; the night is cool.

Come along, we’ll take you with us. To your namesake, to other people, to animals. To the vixen, to Schramm. Into a hunger for life, into the weariness of life. To Frau Kranz, to Frau Schwermuth. To the smell of baking bread and the stink of war. To revenge and love. To the giants, the witches, the bravoes and the fools. We’re sure you will make a reasonably good heroine.

We are sad, we are glad, let us pass our verdict, let us prepare.

HERR GÖLOW IS DONATING SIX PIGS FOR THE FEAST. ONE OF the six will survive. First thing in the morning the Children’s Day organizers inspect the place, and then the children get to pardon one of the pigs.

What for, and what does pardoning mean?

The spits for the remaining five are set up behind the bonfire. The children will be allowed to turn the spits. That kind of thing is fun too.

The Gölow property. Stock-breeding. Products for sale: honey and pork.

When pigs are being slaughtered in summer, in the heat that makes all sounds louder, you can hear their screams kilometres away. Many of the tourists who come to bathe in the lakes don’t like it. A few of them don’t know what the noise is. They ask, and then they don’t like the noise either, and they also don’t like having asked about it. So far as we’re concerned the dying pigs are no problem, dying pigs are part of what little industry we have.

Olaf Gölow walks across the farmyard. Barbara and the boys are asleep. Gölow lay down to sleep as well, but his thoughts kept going round and round in circles: about Barbara’s forthcoming operation, about the Feast, about the ferryman’s death, about the Dutch who have been in touch again asking how things are going.

Gölow got up, carefully, so as not to wake Barbara. Now he is in the farm buildings, in the air-conditioned sweetness of his pigs and their sleepy grunts. He lights a cigarette, breathes the smoke in away from the pigs, turns the ventilation regulator.

Gölow is that kind of man, honest to the bone, you’d say. There are certain moments: for instance once, on a rainy day, he saw something lying in the mud outside the shed. There are certain ways of bending down, maybe they set off a reflex action, that could be it, a reflex action making you think: here’s someone helping himself, look at the way he bends down. There are moments like that, something lying in the mud, an object, and Gölow bends down—broad-shouldered, wearing dungarees, a gold earring in his left ear—and picks it up. He takes his time, in spite of the rain, takes his time looking at it and squinting slightly, looking absent-minded. What’s lying here with my pigs, what is it? Is it a nugget of gold, is it a pen, yes, it’s a pen, why is it here? We’re glad to see a man like that, we think of him as kind to his children and fair-minded when he presses the dirty pen down on his hand, draws a loop on his hand with it as well, to see if it works, yes, it does, and Gölow puts it in his pocket. Later he asks everyone: Jürgen, Matze, silent Suzi, have any of you lost a pen?

Then again: the ferryman owed Gölow money. Not a lot of money. Not a lot for Gölow. Presumably a good deal for the ferryman. And Gölow goes and buys him a coffin. He specially asks for a comfortable coffin. He spends two evenings doing research into coffins on the Internet. Barbara gets impatient: why comfortable, what difference does it make? Gölow says the ferryman had a bad back. Some of the movements you make when you’re rowing, when you’re pulling on ropes, never mind whether you’ve been doing it right or wrong for years, in the end you need a comfortable coffin.

Gölow had known the ferryman for ever. He was already an old man as far back as Gölow can remember. Recently he went out with him several times, taking the boys with him. At last they’re at the age when you can tell them scurrilous stories and they don’t start blubbing, and the ferryman could tell stories that would really unsettle them. Kids love to be unsettled.

Gölow grinds out his cigarette. He smokes a lot without enjoying it. He always has that little tin in the front pocket of his dungarees, the one with the Alaska logo on the lid. He walks past the pigsties. Making notes; Gölow is making notes. With the pen that he found in the mud. We trust him to pick the six best pigs. Obama always pardons a turkey before Thanksgiving.

Obama; Gölow isn’t very keen on him. Talks a lot of hot air. Out of all those American presidents, somehow, Clinton was the only one he liked. They sent him a letter once: the Yugos, Barbara and Gölow himself. That was in ’95. Gölow had a Bosnian and a Serb working for him, and he had no idea exactly what the difference was. Then he found out that they didn’t really know either. They both hated the war. They argued only once about the question of guilt, because there’s always a one-off argument about questions of guilt, but they settled the question peacefully and then decided to watch only the German news from then on, because on that channel everyone was to blame except the Germans—they couldn’t afford to be guilty of anything for the next thousand years, and the two Yugos could both live with that.

The two of them had been pig farmers at home, and knew a lot about keeping pigs. At least, they’d said so when they first came along. Pretty soon Gölow realized that they hadn’t the faintest idea of pig-farming, but they were happy with the pay, and at the time Gölow couldn’t pay all that much. On the black market. Of course the black market or it would never have worked, on account of the visas. Tolerance was the name of the game, they were tolerated here.

It’s years since Gölow thought of the two Yugos, but on such a night as this… Anyway, the letter to Clinton. All the horrors had just come to light, the mass graves, the camps. And then the Serb said: they’ll have to bomb us Serbs. If they only ever make threats it’ll never come to an end. Only not the civilians. No one likes to think of bombed civilians. The Bosnian had no objection to that idea. Well, and then Gölow said: let’s write the President a letter. They both agreed at once, although it was meant as a joke. The Serb dictated it, the Bosnian’s German was better, so he translated it into German, then Gölow tried to guess what it meant and Barbara wrote it out in English. This went on until late at night, and in the end they hugged and wept and posted the letter, addressed to the White House. As sender’s address the Serb had given his own before he got out of the country, to lend emphasis to their request. Next day he thought that was probably a mistake, because if they see that it’s a Serb writing, he said, that’s the place that they’ll bomb first.