8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: DI Owen Sheen

- Sprache: Englisch

MURDER. BLACKMAIL. WELCOME TO BELFAST.DI Owen Sheen vowed never to return to Belfast, but he needs answers about his brother's death. He is on loan from London's Met to the Police Service of Northern Ireland, although before he can dig into the past, he must babysit DC Aoife McCusker on her first murder investigation.As the case slides into chaos, can Sheen put his personal agenda aside? And will McCusker keep her job long enough to ensure that this first case is not her last?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 544

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

3

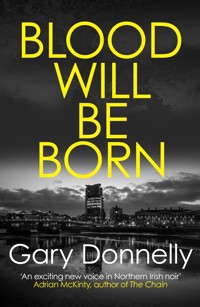

BLOOD WILL BE BORN

GARY DONNELLY

5

For Sacha who always believed

6

You who are bent, and bald, and blind, With a heavy heart and a wandering mind, Have known three centuries, poets sing, Of dalliance with a demon thing.

William Butler Yeats, The Wanderings of Oisin: Book I

It was as if the normal rules and definitions of sanity were pushed aside. Aggressive psychopaths operated without constraint … The psychiatric unit of Downpatrick Hospital, with a brief to treat aggressive psychopaths, had to close during the Troubles because of a lack of patients.

Martin Dillon, The Trigger Men

[In 1790s Belfast] There were many strange ‘disappearances’ of people … known to have been taken by Moiley, as though Moiley was some kind of phantom who took people away … Mothers for years afterwards would scare their children to behave with threats of ‘If you don’t behave Moiley will get you’ … but truth is Moiley did take away quite a few informers, some never heard of again …

Joe Graham, Belfast Born, Bred and Buttered8

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Bog land, Co. Monaghan, Republic of Ireland 1976

Nothing’s as heavy as a dead body.

Better to keep them alive, make them walk, easier over ground like this. Fryer kept his eyes down, careful on each step. The path they were on was barely that: a thin snake of semi-swamped moss and turf, broken up by the odd grey rock or half-dead tree. On either side the bog: black and boundary-less in the dead of night. The wind was in voice, it howled across the land, sending salt spray into his face.

Romantic bloody Ireland: people had killed for this, many more had died.

Mooney’s light faltered, and then faded, fast. He had been leading the way, the boy between them, Fryer’s gun pointed at his back. Fryer stopped, Mooney must have changed direction. Within a minute, a man could be lost. It was the whole point of this place: things came to disappear.

Fryer squinted into the rain. No sign of him. Hovering to his left, for a moment, was the ghost of a light, and 10then it was gone, obscured by the mist. The spray surged towards him, blanketing even the ground, leaving him without bearings. Fryer staggered drunkenly. He held out both arms like a tightrope walker and slid his finger off the trigger, hissing a prayer of expletives under his breath. He could smell the oily looking water pooled at his feet, mineral, decomposed. No way was he going in that.

Fryer’s eyes widened; no longer seeing the bog water. His shoulders hunched and he turned, finger back on the trigger.

‘Mooney!’ he yelled, dropping down on his right knee, gun pointed.

The hairs on the back of his neck raised in an angry heckle, he felt them shiver and crawl; something had been behind him. Close enough to touch him. And now, something was watching him. He stared, unblinking into the blackness, training the shooter between ten and two.

‘Mooney!’ he screamed, but the wind sucked his words away.

His mind raced, recounting the journey that had taken them to this point. They had not been tailed. Fryer was certain of it. Mooney said the Brits were sending in the SAS, men who would lie in wait for weeks on end, then bang bang. Fryer told Mooney he was scared of fuck all, and that was true. But now, Fryer was scared.

He waited, every sense on edge, but heard only the wind. He watched the path. That’s where it was. And he could feel it watching him. Fryer stole a glance in the direction of Mooney’s light. He could see it again, but it was very faint, a hazy yellow glow. If he stopped here any longer, he might not find them. He might end up waist deep in the dark water.11

With IT.

He slowly raised himself up, gun still trained on the path, and took a few tentative steps forward. He peered intently, but there was only blackness and the spray on his face. He slowly lowered the gun. Nothing. It was time to go. Fryer turned, and walked, one eye on the dissipating halo of Mooney’s lamp. He would not run, no need, and if he ran he could twist an ankle, break a leg.

And then it will catch you, because it is still there, you know it. You can feel it on you, watching.

And then Mooney would have to drag him back to the cottage, and Mooney couldn’t drive, there’d be no way to get back to Belfast.

Squelch, sink, suck – next foot, and repeat. Wetter here, less of a path. Fryer panted hard. He checked, but Mooney’s light was no closer, so he set off again, faster, until he was running, or what passed for it, arms swinging at his side, the gun gripped in the wet claw of his hand, eyes on the light, to catch Mooney, get this dirty job done.

A hand, bony and preternaturally strong, hooked round his left foot, and held it under the cold water. Fryer yelped and fell forward, the bog rushed up, his brain manically ordering his numb body to kick, roll and shoot.

Freezing, earthy ditchwater stung his eyes, filling his ears, his nose and mouth, drowning him in blackness. His left ankle exploded with agony, something holding and turning. It was going to twist off his foot, pull his leg from its socket. Fryer screamed into the mud, his finger pumping the pistol’s trigger. Instead, he felt the cold squelch of mossy water in his right fist. He had lost the gun. He pushed himself up and turned, choking out bog water and gasping, 12crying. Fryer started to tug his leg by the calf, his left ankle exploding with agony as he yanked. Fryer looked down, panting, but no longer sobbing.

His foot was caught on a twisted old root; he could see its shiny blackness where it broke the lip of the water like a mummified forehead. Not the bogeyman after all, he thought. Fryer shuffled on his arse, getting closer to it, then turned himself round and dislodged his foot, shoe coming off in the process. He submerged his hand into the black pool, retrieved it. Grimacing, he squeezed his foot in, leaving the laces undone. He turned, and groped about frantically on his hands and knees in the muddy water for the gun, finding nothing but sediment. Finally, he stood up, panting, spitting away the flat, iodine taste of the water. Time to catch himself on here. He’d lost his cool, and now he’d lost a piece. He was going to balls up this operation if he was not careful.

‘Find Mooney, do the job,’ he said into the rain.

He cupped his hands to his mouth, ready to bellow Mooney’s name, though it would have done little good. Then he looked right. Maybe a hundred feet away, he could see it: Mooney’s light, moving ever so slightly, the size of an old penny. Must have tracked too far to his left, overshot them, but he had made up the ground. If anything, he was a bit ahead of them now. Fryer started to move towards the light, trying to keep the weight off his left ankle, but not able to. He gritted his teeth, and welcomed the pain. It was keeping him alert; it was bigger than the wind, a distraction from the foundering cold that wanted him to stop. Fryer plodded on, his gaze fixed on the glow, not looking down. And not looking back.13

His feet found a firmer path, the light cleaner, closer. About ten yards further on, there was Mooney, the boy still in tow. Fryer called him. Mooney stopped, turned round and looked him up and down as he approached. He took a fist full of the boy’s soaking T-shirt and shoved him down, hard. Ahead was only bog; this was the end of the road.

‘State of you, you’re soaked,’ Mooney said.

‘Fell,’ said Fryer, looking over his shoulder into the dark. ‘Foot caught. On a root.’

‘Gun?’ asked Mooney.

Fryer shook his head, not meeting Mooney’s eyes. The boy was sitting on a flat stone, rocking back and forth, whimpering like a wounded cub.

‘Never mind, use mine,’ said Mooney.

The boy squinted up at Fryer, taking him in. He raised both his hands, tightly bound by a piece of nylon rope, and pointed a finger at him.

‘Ha ha you fell, you fell. You’re all wet,’ he said. His face had broken into a stupid smile and then he started to laugh, snot swinging off his nose in a white rope, he was in fits.

Fryer limped over, fast as he could, his gun hand balling into a fist. If not for him, he would not be here, his ankle up like a bap and a missing gun to explain back in Belfast. Fryer got to him, launched a punch and decked him in the mouth, feeling his lips squash and split, the bony barrier of his teeth crunch and give way, loosening under Fryer’s knuckles. His hand was ringing. The boy was screeching, his bound hands muffling the sound as he pressed them against his mouth. He started shaking, and crying loudly, strings of saliva and blood pouring from his mouth. Mooney had his gun out, pointed at the boy’s head.14

‘Shut you the fuck up!’ he said.

The boy stared at the gun, eyes wide, whining, but not crying. Mooney lowered the gun.

‘Mammy, I want my mammy,’ he said, the tears back on.

Mooney raised the piece and cracked him once on the top of the head with the base of the grip. Hit him hard. The boy slumped off the rock, his tongue lolling out of his mouth, lips swelling. Out cold, but probably still alive. Mooney turned to Fryer, a look of genuine apology.

‘I should have gagged him, Fryer. He was quiet, you know, since last night,’ he said.

Fryer sighed, nodded. Mooney understood. Worse than carrying their dead weight was listening to them plead and cry for their lives. Got on your nerves. An informer would say anything to save his skin. He will go to England, and never return. He will never say a word; never, ever talk. It was sort of funny when you thought about it. Talking was usually their problem. It explained why Fryer and Mooney usually dumped their bodies in a public place. The message was as important as the punishment: touts will be found and shot. This was different. This boy was never going to be found. He was to be disappeared. He would not be claimed. That was their orders. Mooney was holding the gun out to him by the barrel. Fryer took it.

‘I did the last one,’ he said. He checked Mooney’s Colt, found six in the chamber and then cocked it. Mooney stepped away from where the boy lay.

‘Where will we bury the—’

Three shots from Fryer in quick succession, the crack of the gun silencing Mooney’s question, the boy’s body jerking as though electrified with each shot, and then he 15was absolutely still. Three holes in the side of his head, darker even than his wet hair, each indented and each still smoking. More acrid smoke hung in the air momentarily, then was cleaned away by the breeze.

‘We’ll weigh him down in the water,’ said Fryer.

‘You take his feet,’ he said, setting the gun next to the lamp.

Mooney nodded and grabbed the boy’s ankles. Fryer grunted, hoisting the boy up by the nylon rope. As they raised him off the ground, a portion of skull flapped open, grey mash and blood within. Fryer raised his eyes to Mooney and nodded. Mooney’s face was pale going on green, but he did what Fryer wanted and turned so they were side on to the where the path ended and the bog water began.

‘One, two,’ counted Fryer, swinging the body with Mooney, and then they both let go, throwing it into the water on three. It hit with a small splash then started to sink, face down.

‘Help me,’ said Fryer, returning to where the boy had been sitting. He squatted over the flat rock. He dug his fingers under it, feeling his nails fill and compact with the soft, black earth, until he felt a turn in the stone. Mooney was doing the same on the other side.

‘Got it?’ said Fryer.

‘Yes,’ nodded Mooney.

‘On three again,’ said Fryer and again they counted, this time heaving and lifting the stone from its resting place and carefully bringing it up. Fryer’s ankle felt like it was made of rusty shards of metal and nerves, but he kept moving, he wanted this over. They walked the boulder into the black water, up to their knees, and then reached the place where the boy’s body had hit.16

‘Go,’ gasped Fryer.

They pushed the weight of the boulder away from them and it splashed into the water, sinking, on top of the body. Now it would never rise. It was over. They sloshed back to the path. Fryer stopped and took the weight off his ankle. Mooney picked up the gun, and kept walking, moving quickly.

‘Where are you going?’ asked Fryer.

‘Piss,’ said Mooney, not looking back.

Fryer felt inside his pocket and took out a busted pack of filter tips. They were drenched, like him. He squeezed the paper packet in his hand and watched as water dripped between his fingers. He pocketed the smokes. He had already left a gun out there somewhere, best to leave nothing else. From a fair bit off he heard the sound of retching and vomiting: Mooney. Fryer lifted up the lamp and started to move in that direction. His ankle blasted mercilessly each time he put weight on it. More sounds of retching. Fryer froze, every cell in his body alive and alert. It was back, watching him, but not from the path like before. It was in the bog, it was behind him.

‘Nothing there,’ said Fryer, to himself, and started to walk.

He heard something over the wind: a slow splash and slop of bog water being disturbed close behind him. Then he smelt it. It was wild, feral as fox piss but also of the bog, wet and cloying as a bag of spoilt potatoes. He ran, swinging the paraffin lamp, crazy shadows lunging at him from the path. The splinters of pain from his ankle were just distant echoes. It was coming for him. It was real but not human and if he turned round he would be able to see it, but that might just take his mind, aye, before it killed him it would do just that.17

His left ankle buckled beneath him and Fryer was falling, for the second time that night, this time letting go a small scream as the path surged up to meet him. He hit the ground hard, and heard the paraffin lamp crack. The fuel ignited with a whoosh and Fryer’s face was hit with light and heat. The spilt oil started to burn brightly on the path, just inches from Fryer’s face. Fryer rolled over and scrabbled away on his back, panting and pushing at the earth with his feet. His eyes were wide, searching for it, but the flash of light hung in his vision, blinding him. It was close, he knew it, its smell was coming at him in waves, fierce as shit, stagnant as a drain.

‘No!’ he screamed, and waved his right arm in front of him.

There was something spraying out of him, cascading through the air. He lowered his arm and saw a shard of glass from the lamp had embedded in his wrist, the blood still pumping out, hot and black. His vision was clearer. He looked up, waiting for the thing to be looming over him, but it was Mooney looming over him, Mooney who was calling his name, cursing, and stripping off to his white vest. He tore his shirt apart and tied it tight above Fryer’s elbow, Fryer groaned, tried to complain, but nothing came out. The blood stopped pumping, and as it did, the first wave of pain hit Fryer, dull and everlasting.

Mooney dragged him up, put Fryer’s good arm round his neck and tugged the back of Fryer’s strides, keeping him on his feet. Fryer’s legs gave up, and then steadied. Mooney was speaking to him. Could he walk, as far as the cottage? Fryer nodded, and they started moving. Fryer could smell the boke on his breath, but that was OK, it was better than 18the other smell. Fryer stopped. He looked back. The oil was sputtering out now, but still burning. He could not see the ‘thing’, but it was there. And it was watching, from the darkness. Its name came to him, as the last flames died.

‘It’s the Moley,’ said Fryer, gritting his teeth on the words, but too late, he had spoken. He had given it a name, and a life.

It knew what he had done and had followed him. If not for the blood, it would have taken him.

PART ONE

BLOOD ON THE BLADE

20

CHAPTER ONE

Belfast, Northern Ireland, present day Friday 9th July

John Fryer slouched in the pee pee chair. He was in the wet room, wearing the disposable paper bib they gave you when it was time for the Friday afternoon sponge down. The garment covered his bits but not much more. Along the hem, printed in blue capitals, Fryer read:

PROPERTY OF BELFAST HEIGHTS PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITAL

Not for too much longer, thought Fryer, staring at the pale, hairy outcrops of his knees. Beneath the stamp of ownership it read:

DESTROY AFTER USE

His hands hung heavily at his sides. He could feel a cool draught on his behind, sagging out of the cavity beneath the 22seat. He stared at his knees, saliva beginning to drool from the left corner of his half-open mouth. But he was alert, sharper than he had been in years. For near three months he had palmed the pink pills he was meant to swallow three times a day, hid them under his mattress.

The door slammed behind him, the sound clean and brittle in the small, tiled chamber followed by the squeak of rubber-soled shoes, getting closer. Ade, the big African fella who had wheeled him in, walked across the room to where a black hose was wound round taps on the wall. He unfurled a length. Fryer was as still as a reptile; only his eyes moved. He heard a sharp screech, and then the hose pulsed and stiffened, water spurted over the tiled floor. When he turned Fryer dropped his eyes, felt icy rain fall on the tops of his bare feet as Ade lumbered towards him. Ade hosed Fryer’s legs, cold water. The paper bib quickly saturated and stuck to his skin, chilling him, but Fryer did not move.

‘OK, Mr Fryer, now’s the time to pee pee or poo poo if you want to.’ Ade squatted down and sponged Fryer’s shanks and did a quick wipe over what protruded through the hole in the chair.

‘No? OK then, easier for me that way.’ He was breathing in short gasps as he went about his chore, his rubber shoes squeaking in complaint as he trudged around the chair. He tossed the running hose into the middle of the room where the floor sloped down. The water gurgled into the open mouth of a drainage hole. It sounded like it was falling a long way down. Ade shuffled round and started to carefully scrub Fryer’s feet. It tickled like fuck, but Fryer only stared at his knees, drool slipping from his slack jaw. ‘Why you never talk to me no more Mr Fryer, huh? You make me 23sad. Maybe I’d give you a pedicure if you talked to me, no? Lots of nice gentlemen they do it these days,’ Ade chuckled, his jest offering Fryer a welcome but momentary warmth, quickly replaced by the hollow echo of the water, falling into that deep, dark drain.

Fryer shivered, gritted his back teeth as Ade’s wet sponge did its work up and down his legs. A man was singing, across the courtyard. The sound leaked in with the dusky Belfast light through the single window above Fryer, steel bars visible through opaque glass.

Your man could hold a tune, but hard to make it out.

Bars on a cell and singing at twilight, just like when he was in the H-Blocks, when he had been surrounded by comrades, and friends, men he had fought alongside with rifle and grenade, men like himself who had taken an oath to one another, to Ireland, to the IRA.

But those boys could sing back then. They had filled up the dead zone of that prison, its galleys and cells and featureless courtyards. They had filled it with songs from the heart, rebel songs, made a home in a place designed to break a man, isolate an army, to destroy resistance.

North and south men had stood side by side, comrades and friends. They’d been on the one road, singing ‘The Soldier’s Song’ together.

Fryer blinked. Your man had started to scream, like a trapped animal.

The H-Blocks were closed up now, empty. He’d heard it was going to be a museum. All his comrades were gone. Some dead though many were free men, but all on different roads now, not on the one road. No one wanted to sing ‘The Soldier’s Song’ any more. No one wanted 24to know him, not even so-called blood brothers like Jim Dempsey, a man he would have died for, the man he had killed for many times. Dempsey had dumped him here ten years ago and left him to rot.

Fryer’s chest tightened under the wet paper. He clenched his teeth once more, but this time not because of the cold.

‘I leave the pedicure for next time, Mr Fryer,’ said Ade, wheezing as he stood up. He trudged to the spewing hose pipe on the floor, still feeding water into that hole. Fryer relaxed his fists, which were balled at his sides, tried to calm his breathing, think of something else, not Dempsey. But no matter what, he would not look at that drain. It was very deep, which meant it was also very dark. And the dark spelt danger for John Fryer. The milky light from the small window was weaker now, and twilight shadows had pooled in the wet room where, minutes before, none had been.

Fryer’s heart gave an unpleasant wallop, and he reluctantly lifted his gaze to the darkening room. Ade bent down and picked up the hose, and as he did so, Fryer caught a glimpse of the black drain. It held his attention as only an awful thing can and he stared into it, unblinking. Sweat pimpled Fryer’s forehead, in spite of the numbing cold. Every nerve cell screamed in unison for him to jump up, run and get the fuck away. Because IT was coming for him, out of the darkness, always from the darkness. And it was close. He caught a whiff, very faint, but unmistakable: something decayed, and yet lively, like a monkey enclosure on a hot day. His pulse beat in his ears, bump, bump, bump, and he breathed in laboured rasps. The cords in his neck stood out as though straining to carry a dead weight. Yes, still time to run, to hide, but to what end? It would 25find him again sooner or later, as it always did. And aside from letting it devour his body, his soul, there was only one thing which John Fryer could feed it, to keep it at bay. Blood, only freshly spilt blood.

The smell hit him. It was thick and damp: wet pelt and black fungus. It had found him.

It was the Moley.

He looked up to the high bars of the solitary window, not caring now if Ade noticed him move or not. The meagre light was fading fast, but any light at all was good. The waves of stink kept coming.

The Moley was closer.

Ade yanked on the hose and pushed Fryer’s wheelchair out of his way. The wheels screeched, and his medical chart clacked against the back of the seat. Fryer glanced there, two words caught his eye, before he turned his attention back to the drain, a man in a living nightmare, not wanting to see but powerless to resist. The Moley’s smell filled the air, coated his sinuses, his throat. Any second now he would see it coming up and out of the darkness. Running was not the answer. It needed to be fed.

It needed blood.

Ade stopped dead and dropped the hose, icy water sprayed Fryer’s feet. He spun round and started very cautiously back in the direction of the drain, head cocked to one side like a man listening for a rare bird call. He froze. Fryer could see that his left hand was trembling. Fryer listened too: the beat of blood in his ears, the hiss of the hose, Ade’s wheezing breaths. Ade’s voice faltering:

‘You hear dat sound, Mr Fryer? You hear that sound just now, yes?’ Fryer was motionless, staring past his 26knees to a cracked tile on the floor. The smell was hammering him in thick waves. If he looked at the drain he would see it now. On cue, Fryer heard Ade gasp, and then watched as he back-stepped. He said something in a foreign tongue and made a gesture with his right hand. He turned back to Fryer.

‘OK, Mr Fryer, let’s get you finished. And then let’s get out of here. It too cold here,’ he said. Fryer was shaking, not from the chill. Ade picked up the sponge and hose. He sprayed Fryer’s upper body, and hastily scrubbed Fryer’s armpits, top of his shoulders, and the back of Fryer’s neck, faster and rougher than before. He ran the sponge down Fryer’s left arm, stopped, then stepped away. Fryer heard him gasp again.

‘Oh, Mr Fryer, I am so sorry, I should be more careful, Mr Fryer.’

Now Fryer felt the sting from his arm, the warmth of his blood, coursing from him. He’d cut him, maybe just pressure from the big sponge. It did not take a lot. His skin was paper thin in parts, a lattice work of scars, like the damaged surface of one of Jupiter’s frozen moons. Countless episodes of cut and heal, blood offering to keep the Moley away. He could see the black ribbon of his blood on the tiled floor, mixing now with the stream of water from the hose. As his blood approached the hole, the stench of the Moley started to recede, and then it disappeared as the blood flowed into the blackness below.

Ade snorted, dropped the sponge to the floor and cast the hose down. Fryer heard Ade slam the wet-room door open, and his huge brown paws encased Fryer’s cold hands and gently guided him into the wheelchair. Ade ripped the 27paper bib from Fryer and carefully wrapped a soft, white towel twice round his lower arm. It throbbed comfortingly under its new duvet. Ade pushed the chair, the wheels squeaked high and low, and Fryer was freed from the shadows of the wet room at last. His chart clacked against his back, reminding Fryer of the two words he had read.

Two words: no sharps.

CHAPTER TWO

Christopher Aaron Moore killed the engine of the London black taxi after pulling to a stop outside his granny’s terraced house in Tiger’s Bay, North Belfast. His hands and lower arms buzzed with the ghost of the old engine’s rattle. He flexed his gloved fingers, the tingling stopped, and the sudden silence was replaced by the faint flutter of the Union Jack bunting, draped between lamp posts the length of the terraced street.

It looked smaller now, and there were more cars, at least one per house, plus satellite dishes pointed skyward, so different from what he recalled. Until now, in his mind’s eye, Granny’s street was an endless corridor flanked by kerbstones; children swinging on ropes from the lamp posts, ball games and dogs chasing. The first, and until now the only, time he had been here, Christopher had been a child too. It had not ended well. Everyone on the street had stopped and stared, to see what the commotion was. The 29commotion was Granny Moore’s shrill voice, coming from this very doorway, breaking like dinner plates down the street, directed at him, and at his daddy.

Don’t either of you come back here! You or that mongrel Fenian taig bastard.

‘Fenian’ and ‘taig’ − the insults were directed at him. What ‘nigger’ was for black America, ‘Fenian’ and ‘taig’ were for the Catholics of Northern Ireland. In his case, not strictly true, but Christopher’s daddy, though a decorated member of the RUC, had also married a Catholic, Christopher’s mother.

Her house looked the same. The window frames had been freshly painted in the same shade of royal blue. The sill was smooth and gleaming white as a surgeon’s smock. Her front door was a glossy fresh red, proud as a postbox in the afternoon light. Red white and blue, the colours of a loyal Ulster Protestant and one who had no room at her hearth for a half-blood like Christopher. Christopher was here to have a word with her about that day. But it was not petty revenge, or at least not completely that, which had brought Christopher back to her door after so many years. Daddy had explained exactly what must be done, told him he had a special mission. The fact that Daddy was dead did not bother Christopher unduly. He had spent too long wandering in the wilderness. Daddy had called him in the night, and he had answered, and he had listened. Daddy told him that Belfast was a fallen place, a Gomorrah of hypocrisy and perverted justice, where evil men now ruled and the just, like him, had been cast asunder. Daddy told him he must bring the refiner’s fire to Belfast, and where better to set the flame alight but here?30

Granny’s front door opened first a crack, then wide. A man with a thick brush of grey hair filled the frame, facing in. He said something Christopher could not make out. Christopher stayed still, but he did not hide. The man tugged the door shut, turned and walked past the taxi, his face briefly visible as he pulled out a mobile phone and gave it his full attention.

Uncle Cecil.

Older, a few more saddle bags and much more grey. No paintbrush moustache these days but definitely him. Cecil had been there that day too, arm round his mother as she ranted, burning contempt in his eyes. Christopher watched in his left wing mirror until Uncle Cecil turned the corner and passed out of sight. Let him go, for now. Cecil had his own part to play. When he discovered what Christopher would leave of his mother he could be relied on to wreak more havoc than Christopher could ever start. When his usefulness had expired, Christopher would deal with him too and then a fire would rage in Belfast, the hypocrites and traitors would be consumed.

But first, the spark. He reached into the passenger footwell for his black mahogany truncheon, tucked it into the inside lining of his jacket and touched the front pocket of his jeans, felt the folded hunting knife. He grabbed the holdall with his change of clothes and towel and got out.

He was wearing what he thought of as the unofficial uniform of a Belfast street Provo from the 1980s (something he was not, had not even been born). Black Doc Martens, a pair of stone-washed blue jeans, a padded bomber jacket and a pair of leather gloves. He unrolled the black beanie down his face to reveal a balaclava, two 31eye holes and one for his mouth. Christopher looked up and down the empty street, closed his eyes and listened to the flapping applause from the bunting, started to smile. The stage was set. Christopher raised one gloved fist to Granny’s gleaming door.

BANG, BANG, BANG!

A policeman’s knock, as Daddy used to say. He heard a muffled voice from within. Christopher moved his mouth to the letter slot and gently pushed it open.

‘It’s Cecil. Forgot something.’

Faintly from within: ‘I only just sat down. Use yer key.’ A litany of muffled curses followed, then the clack and creak of a walking stick or a frame. He released the letter slot and turned his back to the door. The red, white and blue bunting, a sudden riot of colour in his eyes, like so many of his earlier oil-covered canvases. They were now gathering dust in the attic of his childhood home, not hanging in galleries as he had once dreamt. That work was naive, like his wanting to become an artist, of that kind, in the first place.

And yet, Christopher’s face flushed beneath the balaclava; art college rejection letters from Belfast and London, softly worded glasses in the face. He breathed it out, felt his rippling pulse flatten, as the front door unlatched behind him. His calling was higher than all that, and he was about to create a different kind of art, his masterpiece. He could hear her creak and shuffle off, a fair pace on her. She must have warmed up a bit. ‘You are some sort of spastic, son. The age of me, my knees may be shot but least I have my marbles. Hurry you up, my show’s about to start.’ Christopher turned to the open 32door, slipped in. He clicked it closed with the heel of his boot, and slowly walked down the hall.

The smell of an Ulster Fry hung in the hall: fried bacon, sausage, egg and greasy bread. The sound of a television turned way up coming from the parlour further back. A wooden shield with dozens of miniature spoons hung on the wall. On each spoon was a flag of the world. The tricolour of Eire was not amongst them.

To his left, a white door with rectangular glass panels was slightly ajar. The sound of the television blared. The air here was stale with smoked cigarettes. Christopher nudged the door open. Granny was in a high-backed chair diagonally opposite. A grey plastic crutch leant against one of the arms, and a small table was on the other side, with a full ashtray. She was wearing a pair of horn-rimmed glasses and a nylon kitchen coat.

Christopher stepped into the room, reached behind the television and pulled the plug. All was suddenly quiet, only the tick of the clock on the mantelpiece. She stared at him, her mouth open.

‘You’re … you’re not Cecil,’ she said.

‘No, unlucky for you, Esther, I am not.’

CHAPTER THREE

DC Aoife McCusker tapped the big fish tank at the back of the booth where she and Sergeant Charlie Donaldson sat, finishing their Chinese. The lunchtime throng of Belfast Friday office workers and early bank holiday bargain hunters had come and gone, and the place was quiet. Charlie was already drunk. He had polished off five large Bushmills in the time it had taken her to work through one small rosé wine. She could smell the sourness of the whiskey wafting over from across the table and feel his bleary gaze on her.

This was a mistake. She should never have agreed to meet him, the poor guy obviously could not handle it. In the three months since their affair had ended she had shared only a few professional meetings with him, always with others present, despite the fact that he was her boss. Since the last one a month ago, he had lost half a stone of handsome muscle and had black 34bags under his eyes. In contrast, she was flourishing. First week working Serious Crimes, the promotion she had waited for, had worked for. Charlie was no longer her boss. He was just an old flame, and sputtering out before her eyes.

She heard the ice clink as Charlie finished off the dregs of his drink and then a rattle as he shook it in the direction of the young waitress, waiting in the shadows. She lifted a finger and tapped the thick wall of the fish tank again with the tips of her fingernails three times: one for her little girl Ava, one for her job, and one for luck. Another drink arrived.

‘You’re not supposed to tap the tank,’ said Charlie, gesturing to the peeling sign beneath the fish tank. ‘It upsets them,’ Charlie said, his bloodshot eyes meeting Aoife’s over his wire-rimmed glasses. He drained half his glass, smacked his lips. ‘Even fish have feelings you know,’ he said. She glanced at Charlie’s hand, wedding ring still on. Charlie spotted her looking.

‘I know. I should take it off. But I’m not divorced yet.’

‘I am so sorry, Charlie, about everything. I shouldn’t have come today, this is bad for both of us,’ she said. Her apology had escaped unchecked, left a sour residue in her mouth. She picked up her water glass and took a sip.

‘We have been over this. The end of my and Lisa’s marriage was not your fault,’ he said, beginning to slur.

‘Look, you said you needed to talk to me about something, something important. So just talk, and then I should go,’ she said. He raised a hand, shaking his head at her mention of leaving, then picked up a white cloth napkin and padded his greasy lips.35

‘Jesus, Charlie, talk to me. You said on the phone that it was serious, you sounded serious.’ Charlie studied the table mat and palmed the air between them in a slowdown gesture.

‘We can get to that,’ he said, gravely. ‘Yes, we need to have a serious chat, about something serious,’ he said, his stoned eyes fixed on the blue world of the fish tank. This was pointless, if Charlie had important news he was patently too smashed to deliver it.

‘Firstly, however,’ he said, a big grin spreading over his face, ‘firstly we should celebrate. Young lady! Champagne, your best,’ he called, and the waitress promptly scurried away.

‘Charlie, listen to me, I don’t want champagne. I don’t want anything. In fact, I think it best I leave,’ she said. Charlie wagged a finger at her. He drained the rest of his whiskey and set the glass down with a rap.

‘Nonsense, champagne it must be. This is a celebration, Aoife, for a well-deserved promotion. Serious Crimes is lucky to have you,’ he said.

‘Charlie, you are very sweet, and you are a good man, and thank you for all the coaching and help you gave me, I know I would never have got the job without your help, but—’

‘They are lucky to have you. I have never in my days worked with someone who was able to do the job in Community Relations as well as you. You’re smart, you’re fair and you,’ he said, pointing at her, ‘are going to be a great detective.’

But in Community Relations her name was dirt, and reputations had a habit of following you, especially as a 36woman. The waitress arrived with a bottle of cheap-looking fizz in a silver bucket. She set two flutes down and uncorked it with a muted pop, filled their glasses. Aoife picked up one of the fortune cookies from a small bowl in the middle of the table and cradled its delicate shell between her palms.

‘To you, Aoife, you knock them dead, kiddo,’ said Charlie. He was smiling, holding up the flute, his eyes glazed. What a waste of time. Whatever his supposed news for her was, it could not be that important, probably just a ruse to get her back in the sack. She crushed the shell of the cookie between her hands and then dusted the broken bits on the stained white tablecloth, reached for her purse and pulled out twenty quid, looked at the bottle on ice and then took out another twenty plus a ten. She dropped it on the table on top of the cookie dust. Charlie was watching her, mouth open, eyes not understanding.

‘Aoife, darling, what are you doing? We’re having a toast here. To you,’ he said, weakly lifting his glass. She stood up, grabbed her bag and coat and took the bit of paper from the fortune cookie, then shuffled out of the booth.

‘I have to go, Charlie, and I think it’s best if you and I are not in touch, for a while,’ she said, turning before he could say anything else. She marched away, past the waitress in the shadows who stared at her with big, brown eyes, past the bar with no one serving. She paused to read her fortune, frowned then dropped it on the floor and kept walking. From behind her, Charlie’s voice, loud and full of afternoon drink:

‘Aoife, stop. We need to talk. I’ve messed up, badly, I need to explain. Aoife! Aoife! Wait, I’m sorry. Whatever happens, I want you to know that I’m sorry,’ he called. She pushed 37the restaurant door open and stepped out into the bustle of a Belfast Friday afternoon, creating her destiny with confident strides, and leaving Charlie Donaldson’s apologies and the warning she’d found in the fortune cookie behind her.

CHAPTER FOUR

Granny stared at him, open-mouthed, then snapped it closed like a turtle. Christopher eased himself into the two-seater settee opposite her chair.

‘Who are you? What do you think you’re doing in my home?’ Then, before Christopher had a chance to respond: ‘I was just about to watch my show.’

‘Well, let’s go back to who I am not. As you said, I am not Cecil,’ said Christopher.

‘If it’s money you’re after you may sling your hook, for I have none,’ she said, face set. Christopher told her that theft was not his intention, though he noted she was sporting a fair-sized sapphire on her right hand, too big to be the real thing. Something like that could go for a grand in the Cash Exchange in the city centre. She squinted at him through her thick spectacles.

‘You know my name. So do I know you? Let me get a better look at them eyes.’39

She adjusted her position, craning forward, moving her arm from the chair as she did so. She seized something from the table, faster than Christopher had given her credit for. Like a rat. Christopher could only stare at the plastic alarm on a drawstring now clasped in her hand. It was concealed behind the ashtray. She jabbed the red button, glared at him triumphantly.

Christopher’s paralysis broke. He whipped the truncheon from the smooth nylon lining of his jacket, pouncing up from the settee as he did so. He swung it through the air in a tight arc, all of him lasered in on the blinking alarm and the scrawny claw that continued to jab at it. The hard wood truncheon connected and Granny’s hand gave a brittle crunch, the alarm dropped to the floor, and she threw her head back, the cords in her neck like metal rods sheathed in thin paper. Her first scream, hoarse and brief, was followed by a big, gasping inhalation, then a long, sharp howl which tailed off first into a whimper.

‘Bastard! Cecil will take your life for this.’ Her left hand was swelling and turning purple.

‘That was worth a rap on the knuckles, Esther,’ said Christopher, voice steady, but his heart was yammering. He needed to switch on. The old woman had managed to check him, his next move needed to be smarter still, and fast. He rested the truncheon on the settee, then scooped the alarm off the floor and examined it. He found the number he was looking for.

‘Here’s the deal, Esther. I’m going to make a phone call and tell them that everything is A-OK. You are going to keep your wee mouth closed and in exchange I will keep this’ – pointing at the truncheon – ‘away from that.’ He 40pointed to her damaged hand. ‘Then, you and I will be able to have a civilised chat. Deal?’ She blinked away tears from her eyes and nodded once.

Christopher got up and lifted a cordless phone from its cradle by the door. He punched in the number printed on the back of the alarm and a woman’s voice answered. He gave Granny’s user ID that was written on a sticker under the emergency number, confirmed the address and identified himself as Cecil Moore, Esther’s son.

‘Ma accidently pushed the button. Aye, she surely was wearing it. Just glad I was here, she got herself into a right fluster, you know how they get? OK, thanks very much for your help. You have a good weekend. Oh, aye, thanks love, you enjoy the 12th weekend too, we will,’ he said and ended the call, his eyes on Granny throughout. Christopher held the alarm, still flashing, by the string and let it pendulum back and forth, like an old-fashioned hypnotist. Granny watched it move and blink. Seconds passed. The alarm stopped blinking.

‘Now, that’s magic,’ said Christopher.

The laughter erupted, surprising him almost as much as his granny, who flinched and then shrunk away, as though it were a contaminant. He wanted to stop, but Christopher simply could not. He laughed until his face ached and his eyes streamed, leaving the balaclava damp against his cheeks. He screeched until he was gasping for air. Christopher tossed the alarm on the carpet and gripped the settee. His outbursts had been a problem since puberty, but recently things had started to get much worse, and in moments like this Christopher was certain he was—

Mad?

He was losing control, in a way that he may not be 41able to regain it at all. Hearing Daddy’s voice was one thing, a welcome gift of great value. But this was bad, and if he didn’t catch a grip soon, the old witch would make another move, she had it in her. If she somehow got the better of him (an absurd idea, and a truly horrible one which, until this moment, he had not even conceived of), he would never complete Daddy’s mission, he’d be dead if she managed to call Cecil. But there were worse things than death. If he lived he’d end up locked away. People would not understand, they’d say he was nuts, like his mother. At that, the boiling spring inside him went cold and quiet again, the laughter stopped as abruptly as it had begun.

‘Who are you?’ said Granny.

‘Don’t you know, Esther? You can’t remember me?’

‘I know what you look like, sitting there.’

‘What’s that?’ Granny did not reply but eyed his attire up and down, disgust evident, but no more afraid now than she had been when he first surprised her. ‘An IRA man you mean? Yes, I suppose I do at that. But this here is not exactly an Armalite rifle, is it?’ He lifted the truncheon from the settee and slowly waved it at her. She did not respond. ‘This is police-issue and proper: RUC. This is a skull cracker.’ He thwacked the stick into his gloved palm. ‘A Provo, or maybe I should say a mongrel Fenian taig bastard with an RUC truncheon, that’s something you don’t see every day.’ Granny’s face shifted from confusion to recognition, and then, most pleasingly, to fear. Her voice small and quaking:

‘Christopher? Christopher, is that you?’ she asked. Christopher slowly unrolled the balaclava from his face and made it a beanie hat again. He observed her coldly, the residue of his false tears cold on his skin.42

‘I’m sorry,’ she said.

‘What for?’ asked Christopher. She paused before answering, choosing her words like chocolates from a mostly empty box.

‘For what was said. What I said. That time, to you and your da.’ Straight to the nub; she remembered. But did she recall it as Christopher could? The memories planted in fear by a child have the deepest roots of all and they live on, nourished by the bitter waters of injustice.

Twenty-five years ago, her skin more taut, more meat on her bones, her hair fuller and still a lot of depth and thickness to her grey. She had her Bible under one arm and Uncle Cecil by her side, while his daddy marched him away from her door.

Don’t bring him back here! Don’t either of you come back here! You or that mongrel Fenian taig bastard.

‘Where’s your Bible, Esther?’ asked Christopher.

Her eyes moved to the shelves on the wall to his left. He saw it: top shelf, big book, bound by brown crenelated leather. He got up and slid the book from the shelf, just about able to hold its weight with one hand. He rested it on his knees.

‘That was a long time ago, Christopher,’ she said. Christopher noted her tone, reasonable, gentle and the fact that she had started to use his first name. But she was not going to oil her way out of this. She had outfoxed Christopher once, and once was enough. Her puffed-up hand was twitching to a beat of its own. He would never be able to get that ring off easily now, even if he had wanted to.

‘A long time ago, Granny dear, but that diatribe of yours caused a lot of damage, a lot of pain. Not that you are interested.’

‘I am,’ she said.43

‘No matter, that’s not the real reason I am here. The real reason, you could say, is that.’ He nodded to the wall above the mantelpiece where a rectangle of orange, bobbled wallpaper was a deeper shade than the rest of the chimney breast. Christopher recalled the big print of Ian Paisley, the firebrand preacher, in full voice outside Belfast City Hall, the epitome of all that was fixed and immutable in the world. The sign behind him in massive red letters:

ULSTER SAYS NO!

‘I don’t understand,’ she said.

‘Last time I was here, it was Ulster Says NO! No?’

‘It didn’t work there no more,’ she said, sniffing and raising her eyes to the ceiling, haughty on matters of hearth and home. Then, back to sweetness and reason, ‘I told you I’m sorry. About all of it.’

‘The big Ian we used to know has gone away − from his pulpit, from your wall and from your mouth, Esther. I heard you interviewed in the news a while back saying what a great thing it was that all parties had voted to work together to support our “wonderful new PSNI”,’ he said. No response from Granny.

‘What they did, when they destroyed the RUC, it killed my daddy,’ he said, pointing the finger at her. She looked away, but answered this time, wire in her words.

‘Your beloved daddy killed himself,’ she said.

‘Shut your mouth!’ he yelled, and she did, but the words stayed as Christopher opened the Bible and thumbed through the pages, then stabbed his finger on the passage he wanted.44

‘What I said on the TV was no different from anyone else, Christopher,’ she said.

‘It was different from you. The old you,’ said Christopher.

‘God’s sake, boy, grow up!’ she shouted. ‘Times change, sometimes everything changes!’

‘But not for the better,’ whispered Christopher. He started to read:

‘Whatsoever causes you to sin, cut it out. If your arm causes you to sin, cut it off—’

‘Stop it! Listen to me,’ she said. She was crying again.

‘If your eye causes you to sin, pluck it out.’

‘I said sorry. They will know it’s you, that you’ve been here,’ she said.

Christopher clapped the Bible closed, stood up. He rolled the balaclava over his face, pulled out the hunting knife, and unlocked the blade with a click. The upper portion was serrated, like a saw. He put the knife on the mantel beside the clock, still crunching off the seconds. Granny whimpered.

‘It’s that tongue of yours, Esther,’ said Christopher, lifting the truncheon from the sofa. ‘Always was your problem.’

‘Your Fenian cunt of a mother stole my son! Nothin’ good could come from it, and look at ye! Look at ye!’ She spat loudly, and a string of saliva landed and clung precariously to the head of the truncheon. Christopher flicked it to the floor.

‘Ah, Granny,’ he said and raised the truncheon over his head like a tennis player ready to serve. She started to scream. ‘Flattery will get you nowhere,’ he said.

One good hit, a policeman’s whack, was all it took.

PART TWO

BLOOD ON THE STREETS

46

CHAPTER FIVE

Belfast, Northern Ireland, present day Saturday 10th July

Fryer was awake.

The only sound in his hospital cell was the faint drone from the overhead fluorescent tube. It cast a sickly, yellow light but shadows remained. Outside the clock tower struck two bells. Fryer was sat on the thin mattress, watching a shadow in the space beneath his desk. He did not blink, and his eyes slowly filled with tears that trickled down his face. His vision started to blur and as it did he saw something slither in that pocket of darkness. Fryer scrubbed his eyes with the back of his hand, scrabbling for the Buzz Lightyear torch. It was child friendly; tough, moulded plastic, no glass or removable sharp-edged lens.

Weak, white light filled the cavity. There was nothing there. The painted green floor merged seamlessly into the wall of the same colour. He lifted his nose and inhaled slowly, got the lingering farty smell of overcooked cabbage, the ever-present liquorish undercurrent of disinfectant. But 48he could not detect its smell: the caged animal smell, mixed with rotten potato mould.

The Moley had been close in the wet room, Ade sensed it, spooked him. Made sense. When you owned a dog, some were going to hear it bark, and hear it howl. Bark and howl, like Shane, his boxer cross. A memory, glinting like a poison shell on the shore of Fryer’s mind: Fryer rushing to decant the blood from Shane’s still-warm body, crying as he did it and saying sorry over and over again. He had needed to work fast, before the blood thickened and spoilt, painting himself into a safe space.

Fryer shook the thoughts away. Without the pink pills he could remember things that he would gladly bury for ever, some good, most bad. Cradling his baby son in the night so many years before, and the news that the young man he had become had died. Killing Shane and using his blood, Jim Dempsey leaving him here, comrades no more. And the night him and Mooney had killed that young fella, McKenna. That was his name. Killed him and Disappeared him in the bog. Killing was never a problem for Fryer, but he had a code, and that night, he broke it. And he had to pay: the very same night the Moley had found him. Fryer had even recalled where he had locked up his old black taxi. So much else was gone, but these things he knew. And he recalled what the kid, Christopher, had said: By 1st July be ready, be clean; no pills.

‘If you play catatonic, play a dummy, John. They will soon start to treat you like one, and that’s going to help us get you out. But those pills cloud your brain, John,’ the kid had said, tapping his forehead, looking at Fryer. To Fryer, anyone whose chin and temples were not yet grey was a 49kid, even though most of the black Irish still remained in him. But Fryer was no kid. That he knew all too well.

When Christopher first started to visit, Fryer was suspicious. After a few weeks of silence from Fryer and lots of talk from the kid, Fryer looked forward to seeing him as Christopher brought rolling tobacco. He was always on time, Friday morning, 10 a.m. That mattered, another living soul you could depend on. You lived and died by routines in the Heights.

The kid appreciated that the world had fallen down the rabbit hole. IRA men who had been in prison with Fryer, men like Jim Dempsey, were wearing suits and ties and in government with true blue loyalists, and all of them sucking on the tit of Westminster, pumped full of money, making them fat and sleepy and corrupt. You had to hand it to the kid, he had a way with words. He told Fryer the story of his peeler father and how he had strung himself up after the RUC was disbanded, his medals worthless, his commendations defunct.

‘How would you feel about shaking things up a little, John? How would you feel about shaking things up a lot, starting with Jim Dempsey?’ said Christopher, smiling at him.

‘Are you a Dissident?’ Fryer had asked.

‘Do I look like I am some kind of drug dealing half-wit, being run by Special Branch?’ he asked. Fryer had shook his head. ‘No, you are correct. I am not. I am the orphan child of the Good Friday Agreement, John. I am the new you, but in a world where there are no more rebels and no real loyalists. Follow me, John. I will set you free.’ Fryer said he could be persuaded, anything to pay Dempsey a visit.

After that, Fryer had started to talk; he told him 50