8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: DI Owen Sheen

- Sprache: Englisch

WHEN ONLY THE DEAD HAVE THE ANSWERS, WHO CAN TELL YOU THE TRUTH? DI Owen Sheen and DC Aoife McCusker are working for the Serious Historic Offences Team in Belfast, although the hands-on approach of the chief constable and the political agendas at play are a struggle to manage. A cryptic message from a retired, and now missing, cop preys on Sheen's mind. Tucker Rodgers claims his friend has been killed and now someone is coming for him. Sheen and McCusker's search for Tucker and the truth places them in the path of the most notorious IRA double agent of the Troubles, as well as someone else with an old score to settle .with

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 501

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

3

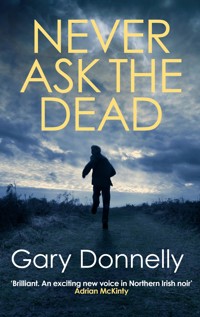

NEVER ASK THE DEAD

GARY DONNELLY

5

For my parents Christine and Paddy Donnelly All you had you gave us

6

‘… be a great feigner and dissembler … a skilful deceiver always finds plenty of people who will let themselves be deceived.’

Machiavelli, The Prince

Why is it we never ask the dead,

Who form a scabbard for a blade,

Their flesh a bullet’s bed?

‘Why you were lost

From breath and put to clay?

Why were you taken and not saved?’

Go on, and dig in the cold ground

Linger not on orders obeyed

Or fates misaligned.

Speak the name that’s chiselled

On the wind-weathered marker.

Ask the price of their blood,

Weigh their hearts on Anubis’ scale,

Know why them and not you, or I.

We never ask the dead, we fear

Not their silence, but their reply.

They say: ‘My name mattered only

Because it mattered less.

You were late, but I was on time.

Ready in the wrong place, lesser than,

And the next in line.’

Fragment of a poem by Roddy Grant, originally part of his scrapbook, TOPBRASS: A SECRET HISTORY

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Strabane, a border town. County Tyrone, North-west Northern Ireland. Late December 1979

The rusty glow of a street lamp rippled in puddles outside the fortified police station, and the cold and unforgiving rain fell. He splashed straight through them, his feet already soaked, and approached the armoured hatch where he would be seen and there waited. He didn’t need to rap or call for attention. They had already spotted him and would be watching him right now, assessing the solitary, dark figure who stood, soaked to the skin, as 1979 ticked slowly down to detonate a new decade. The Christmas cessation of violence observed by the IRA – annual alms to overworked volunteers, their assorted enemies and the long-suffering people who lived day and night under the cloud of the Long War – still held, but only just. They’d promised two days of peace, and the clock was ticking. At midnight, the war was back on, and the witching hour approached. The peelers and Brits who eyed him through peepholes and on the green, fuzzy output of a concealed 10camera probably did so with both trepidation of what he might be, and annoyance that he was bringing them any kind of work at all during this lull. After a time, he heard the unbolting of the hatch and it opened, wide enough to show a pair of eyes and the muzzle of a gun.

‘Yeah?’

‘I need to speak to the Branch,’ he said. Special Branch. The secretive army within the Royal Ulster Constabulary, RUC. The Branch had its origins in the Metropolitan Police’s Special Irish Branch, to give it its original and correct title. They had been tasked to deal with the Fenian dynamite campaign against English targets in the 1880s that was organised by Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa. Almost a hundred years later and another war was on, and there were more bombs exploding than Rossa would have ever dared hope. A pause from the cop who appraised him from behind the hatch. His eyes narrowed.

‘Who are you?’

He glanced away, not wanting his face to be seen. ‘A friend,’ he said.

Which could mean many things. The peeler kept the gun pointed on him, waited for more but got only the hiss of the unrelenting rain. The cop told him to hold on and quickly snapped the armoured hatch shut. As expected, he wanted to call it in. The man who stood in the rain could be anyone. A plain-clothed soldier, coming in from the cold, his cover compromised; a Branch man who needed help and would trust only one of his own in the secret police; or a mad dog Provo that had a gun in his waistband and wanted them to open the gates before he started shooting, happy to go down fighting so long as he took more of the 11enemy with him. But he was none of the above. Here, in the cold and rain, nearly eighty miles from his Belfast home, he was undergoing a metamorphosis. There was dark magic at work this devil’s hour, and in truth, he did not know what he was in this moment, nor what he would be transformed into. The sound of a bolt snapping, and another hatch opened, above him this time, and then a voice. English, barking as only a Brit soldier knew how.

‘Hands on your fucking head. Now!’ He didn’t bother to look up, he knew that the proboscis of a standard long rifle was trained on him. He did as asked, and the door that was set into the large armoured gates was unbolted and quickly opened. Two RUC officers, flanked by two soldiers, emerged and fanned around him, guns pointed. One of the peelers let go of the semi-automatic rifle he was holding and swung it on his back, then frisked him.

‘He’s clean!’ he shouted.

The two Brits seized him and marched him through the gate. He was half carried, half dragged across a rutted and waterlogged courtyard where armoured Land Rovers were parked. His bruised and battered body screamed out, but he gritted his teeth and did not give voice to his pain. He had screamed enough in the last two days. This night, he would speak his revenge. Through a door and along a corridor, the smell of frying eggs and the sour reek of sweat, talcum powder and the humidity of hot showers. A door opened by one of the peelers, and the Brits who had him by the arms stopped. He braced himself to be thrown into the room head first, but the hands released him and the young men marched away. A big hand pressed between his shoulder blades, firm but not aggressive, and he obeyed 12the assertive suggestion that he enter the room. Inside was a table with two chairs. One peeler followed him in, invited him to take a seat which he did, but reluctantly. The cop pulled out a chair and sat opposite. Average height and build, dark hair in a middle parting that fell in curtains on his forehead. Maybe in his late twenties, older than he was. The cop wore a small moustache that suited him and had blue, intelligent eyes. They rested on his face and then creased into a concerned question.

‘Do you need a doctor?’

He shook his head, though it still pained his neck to do so. His eyes were almost swollen closed, and black as the night he’d just emerged from. One of his lips was up like a tractor tyre, and that was what could be seen. His body was a cloudscape of bruises and broken skin. At some point, he would need a doctor and some antibiotics. But the medicine he needed first and foremost was not going to be dispensed at a pharmacy. The peeler asked him if he was sure and he said, quietly, that he was. In fact, it was sitting in the chair that he had a problem with, and part of him understood that perhaps he always would. They’d tied him to one in the isolated barn in South Armagh where they had set to work on him so systematically. It was a dark art to beat a man for three days, inflict the greatest possible hurt and yet manage to keep him breathing, not have him die from shock or blood loss, or rupture a vital organ, to have the temperance and clinical control to keep the blows to the head to a minimum.

‘I want to speak to the Branch,’ which he knew without being told this man was not. He expected him to ask his business. 13

Instead, he said: ‘You any ID?’

‘No.’ He had a return bus ticket to Belfast and the clothes on his back. He’d left his wallet and anything that could identify him in a locked drawer in his home, and he hoped the state of his face would mean those who’d seen him here, so many miles from his locality, would barely recognise him in the light of an average day. The peeler tensed. He braced himself for the Brits to re-enter and lift him up by his sideburns, and drag him to another cell where two men would push his wrists back, bending them against the joint until his tendons screamed while a third crushed and twisted his already broken bollocks. He had been lifted before. First during internment in 1971 before he had joined, and a couple of times after he had raised his right hand and swore allegiance to the IRA. Promises, promises. He knew the drill. But the peeler didn’t make a move.

‘There’s no Special Branch officer present in Strabane station,’ he explained.

He shrugged but said nothing in response. The peeler drummed his fingers on the table. He could feel the cop’s eyes on him. Silence ensued. The peeler pushed back his chair and left the room.

As soon as the door closed, he stood up and slowly started to pace, feeling the cold that seemed to have seeped into the bones of his feet, feeling the myriad of hurts, remembering them as they were administered, remembering all of them. When you torture a man, he will say anything, agree to anything, admit anything. First, he will beg for his life and then, he will plead for you to kill him. The men who had worked on his body in shifts with the thick wooden paddle, 14the iron ball on a chain, the electrodes rigged up to a car battery, had taught him this. Every man can be broken. It was a long time and he was no longer the person he had been, that the man who had ordered his torment had visited. His Officer Commanding in the Belfast Brigade of the IRA. He’d shook his head, a look of disgust on his face. As though being tied to a chair, looking like he did, and reeking of his own urine with his trousers and thighs smeared with his own faeces had been a choice.

‘Someone’s here to see you.’ His OC had pulled his wife into view and clasped her face in his hands, forced her to stare at him. He’d felt the touch of an iron bar under his chin and he too was forced to see. Her eyes full of glass and fear and abhorrence. She had looked at him in a different way the last time they had met. But then, he had been a different man. She was released and she ran out of the barn in tears.

‘There’s plenty of tail in Belfast. But that one’s out of bounds. Understood?’

‘Yes.’ It was only then that he realised he might actually survive this.

‘Good. Then we’re square.’ He could not believe his ears. Not a question and delivered like a man paying a restaurant bill. His OC was staring at him, wanted him to reply.

‘Thanks,’ he’d said.

In Strabane station, he had retreated to a spot on the floor in the corner of the room when the blue-eyed peeler returned an hour later and set a plastic beaker of water on the table. If he was surprised to see him on the ground he didn’t show it. 15

‘I’ve made a call. To Belfast. Someone is on their way,’ he said, and took a blister of aspirin from his shirt pocket. He popped four from the foil and put them on the table beside the water and then turned and made to leave.

‘Thanks,’ he said, not yet ready to move from where he lay.

The peeler nodded and left the room.

Time passed. He drank the water and took the pills. At first, he did not sleep. But he must have nodded off. It was gone six in the morning when the door opened again.

‘So let’s have a look at ye.’ The man who had entered and now closed the door behind him did so on a wave of sparky energy, despite the hour. He was well over six feet tall, and unlike the peeler he wore plain clothes: a brown corduroy sports coat over a shirt and V-neck jumper combo, and a pair of expensive-looking slacks. He had a groomed beard and blonde hair that was almost flaxen and swept off his face. Like a Viking modelling for a clothes catalogue. The newcomer strode over to where he was curled up in the corner and hunkered down, face-to-face. His eyes were a blue-grey and cold, like the inner wall of a shell washed up on a northern shore. He smiled. ‘Don’t tell me, I should have seen the other guy,’ he said and raised himself up. He clicked his fingers and pointed at a seat as he sat down at the table. Belfast accent but not plummy, despite his attire and swagger. He limped over to the table, sat down.

‘Are you a Branch man?’ A warrant card fell with a slap on the table. It said Special Branch.

Name: Samuel Royce Fenton.

‘Read it and weep. That’s legit. Now, to whom do I owe the pleasure of unpacking my cock from the arse of 16that wee WPC I left in bed, not to mention the death of a morning’s golfing I had planned?’

He doubted whether the weather would permit anything in the way of golf unless things had changed utterly since he arrived here. He hesitated, but only for an instant, and thought, This is what it is like to stand on the precipice of another world, and then he spoke, told Fenton his name, where he was from.

‘You’re IRA,’ he replied without hesitation. It wasn’t a question, and he didn’t confirm or deny, but he was correct. ‘I’ve heard of you. Connected,’ said Fenton, slowly pointing a finger at him, that cold smile on his face again. ‘And here ye are. Not that your ma would recognise you.’ Not an accusation, and no disdain in his voice. If anything, the big man seemed awed. He stopped pointing and thrust his hand over the table. They shook. And that was that. He knew it as soon as he took Sam Fenton’s hand that he had crossed a divide and he could never, ever return. And he felt nothing at all. When he’d been dumped on a country road after they released him from the barn, he had just one loyalty left in the entire world and that was to himself.

Fenton stood up abruptly. ‘Mon the fuck, this place is a shithole. Let’s go for breakfast.’

He navigated them out of Strabane RUC station as though he owned it, and they accelerated west out of the town. The dawn was leaching the night from the sky behind them, weak grey replacing the blues and blacks that they pursued west. They approached the Lifford Bridge that would take them across the River Foyle. The river was the border with the Irish Republic and up ahead was a security checkpoint, manned by police and British 17Army. All vehicles were being stopped. He turned in his seat and looked at Fenton, who returned a small wink. A big peeler with a hat on and wearing a thick bulletproof vest raised his hand, and Fenton slowed to a stop and rolled his window down. He passed his warrant card to the cop before a word was exchanged. The peeler took a few seconds to absorb it, his features moving from scrutiny to recognition to looking mildly perturbed. He handed it back quickly and barely glanced at the passenger seat, wishing Fenton a good day.

‘Free State?’ he asked as they left Northern Ireland behind them and entered the Republic, County Donegal.

‘We need a bit of peace. To talk,’ Fenton replied. Which was probably right, but here he had no jurisdiction, and the legally held personal protection weapon he no doubt had secreted was a criminal offence to possess. They drove along winding, high hedged country roads for almost half an hour, deeper into the green recesses of Donegal, the light of the new day awakening colour from the land. Fenton pulled in without indicating and stopped with a skid on a gravel clearing at the front of a whitewashed pub with no name. When they got out, he could smell turf smoke and saw a green An Post van and a white Ford Cortina with Garda emblems and a blue line down the side. Fenton rapped the closed door and gained entry. They sat in the snug, away from the smattering of uniformed Garda officers and postal workers who appeared interested only in minding their own business and drinking, illegally, without hassle.

‘Early morning house,’ he commented.

‘The same,’ confirmed Fenton, who sparked up a Dunhill filter and tossed the maroon box his way. He accepted the 18flaming match and took a draw while Fenton ordered them both pints of stout, and bacon and eggs. ‘Sláinte,’ Fenton said as they had their first sip, surprising him with his use of the Irish language. ‘Oh aye, I know my Gaelic.’

Food arrived quickly and he surprised himself by eating the lot, though noted that his companion chased his round the plate. Fenton waited until he had finished.

‘Talk to me,’ Fenton said.

He did. Told him the whole thing, left nothing out. And then talked some more, like a man with a dam in his head that had ruptured. This man, he had a way. He made it easy. Charismatic was not a word he would have used at that time in his life, but Samuel Royce Fenton had it to spare. In fact, Fenton appeared, from his fallen perspective, as the unadulterated incarnation of it. When the words dried up, he checked his watch. He’d been talking for more than an hour.

‘So, there it is. Everyone has their reasons. And now you want to come and work for us?’ asked Fenton.

He shrugged. ‘I’m done. My war is over.’ He took a second smoke.

Fenton grunted at this, gave him a wry smile through the fug.

‘Mate, it’s not just your fight that’s over. The IRA and the British have already fought this to a stalemate. Sooner or later the talking will start. Then there’ll be peace, and sharing power, you can take that to the bank. I mean look at France and Germany, tucked up in bed together like the Second World War never happened. Someday it will be the exact same here between the Brits and the ’RA.’

‘A man could get an OBE for that kind of loose talk,’ 19he observed. One behind the ear. Street slang for a single bullet in the back of the head.

‘Oh, for a lot less,’ said Fenton. ‘But it’s true. You’ve made the right choice today. For the first time in your career you’re on the right side. The winning side,’ Fenton said.

‘I’m not interested in serving the Crown,’ he replied.

Fenton threw his head back, laughed from his ribs.

‘I didn’t say you were,’ he replied, and his face became sombre. He pointed the serrated knife that came with their breakfast at his chest and then across the table at him. ‘This winning side. You and me.’ Fenton jabbed the knife towards the low ceiling. ‘The higher you go, the higher I go,’ he explained.

‘Sounds like I’ll be doing all the work.’

‘There’s fifty large in cash every year for you. Anything you make on the side is your business, I’ll not interfere. But you’re going to need a new name, a codename.’

He thought for a few seconds and then pointed to the steak knife in Fenton’s hand. Fenton shook his head, said that would not work. Then he stubbed out his smoke and clicked his fingers.

‘Topbrass,’ he said.

‘Seriously?’

‘It’s exactly what you will be. Untouchable, my friend, you’ll go all the way to the very top.’

The sun was fully up as they travelled in silence back towards the border. Fenton agreed to drop him off on the outskirts of Strabane and he would take the bus back to Belfast. They agreed on a story that would cover his absence. They crossed the Lifford Bridge as a mushroom of grey-black smoke rose in the distance ahead of them, followed a few 20seconds later by the sound of the explosion, like rocks rolling in a steel drum. Strabane had been bombed, yet again, and the IRA Christmas cessation was at an end. He watched the smoke drift in the wind, wondered absently if anyone had been killed and if the buses would be running. When he caught a glimpse of his reflection in the wing mirror, he almost didn’t recognise the bruised mask that looked back. And the name that came to mind was not his own, it was Topbrass. Even though he had walked in and freely offered himself, he could not shake the feeling that he had been snared by this dark Messiah, a fisher of men who had called on him to drop his nets and had renamed him in his own image.

PART ONE

THE REPENTANT LUDDITE

22

CHAPTER ONE

Belfast, Northern Ireland Present Day

As the Liverpool ferry drew away from Belfast harbour on Thursday evening, DI Owen Sheen felt the buoyancy under his feet, and watched as the dockside slowly slipped past. He breathed in the sea air and raised his face to the dark sky, the stars bright and seemingly close enough to touch, if only he reached out his hand. Instead he raised the pint of Guinness he’d brought on deck and took a long, thoughtful pull. Sheen was off to London for the weekend. His old DCI’s retirement party. And though he would miss the charms of Aoife McCusker, he was ready for a break. Hopefully he’d grab some kip on the overnight crossing and then it should be a straight drive down to London early doors. It was a long haul, but it was still better than flying.

As the boat picked up speed at the mouth of Belfast Lough his eyes found the twin yellow cranes in the Harland and Wolff shipyard and from there, tracked along the line of the coast to where he estimated the small district of 24Sailortown had once been. The dockside community had been constructed on reclaimed land in Belfast harbour and had first housed rural families from across Ulster, fleeing the ravages of the Irish Famine in the 1840s. It also had been home for Sheen and his family, the place where he had spent most of his first decade. Until a car bomb had exploded on the street where he and his brother had been playing football. Sheen had survived. His brother, Kevin, had not.

Sheen closed his eyes, summoning memories from his childhood that he knew would not come. Like Sailortown and like his dead brother, Sheen’s Belfast years had been erased from existence. All that greeted him from the darkness of his mind was the usual snippets: vignettes of violence from his brother’s last moments and snapshots of the subsequent disintegration of his family. After his brother was killed and his mother drank herself into an early grave, Sheen and his father took a one-way flight to London. The start of a new life and the point at which a door closed in Sheen’s mind, shutting off all access to the old. That awful journey had been his first experience of flying. Little wonder he associated air travel with anxiety and fear. He took another draw from his pint and felt his phone buzz in his jacket pocket.

Chief Constable Stevens. Sheen’s boss.

The chief had taken a hands-on approach to his new role as senior officer linked to Sheen’s unit, the Serious Historical Offences Team or SHOT. Sheen was still in charge, ostensibly anyway, but since things had restructured at the start of the new year the chief had been a constant presence. Regular visits, regular briefings and updates. To 25be expected, Chief Stevens had positioned himself at the helm precisely to keep an eye on how things were being managed by Sheen. To help him ‘steer clear of choppy waters’ was how he’d phrased it.

To be fair, two of the cases Sheen had so far been involved in had respectively contributed to the devolved political parliament in Northern Ireland being suspended. As well as an embarrassing cross-border incident with the Irish Republic, followed by press revelations about historic child abuse and murder involving establishment figures in Belfast and Westminster. Put in context Sheen could actually accept the tighter leash, for a period of time anyway. But if the last couple of months were anything to go on, it seemed clear that the chief expected complete strategic control.

The first case the newly reformed SHOT had worked on this year was the death of a young woman in West Belfast some forty years before, who had been shot from a passing car while standing at a bus stop. Originally assumed to have been a case of indiscriminate sectarian murder, Sheen and the team had discovered an undercover unit of the British army was responsible. Soldier G, who had pulled the trigger, was now seventy nine years old and facing a murder charge. Sheen had wanted those in charge but came up against a brick wall. Convicting one retired squaddie was not his idea of success or justice for the family of the murdered woman. Sheen was not the only one who was pissed off. His team was buckling under the pressure, internal divisions starting to show. Sheen read the message on his phone and sighed.

Get up to speed on the Cyprus Three before our meeting next week. 26

The Cyprus Three. Sheen already knew enough without doing the homework task. And he also knew that the chief’s text was as good as a written command to investigate the historic case. Which, no doubt, would be forthcoming.

The Cyprus Three was the name given to three IRA operatives, two men and a woman, who had been shot dead by the SAS in Cyprus in 1987. The IRA members had been in the process of planning a bomb attack on British troops stationed on the island. Though technically outside British territory, the SAS had been called in after local law enforcement had somehow got wind of a planned attack. The presence of the SAS was unusual. But given the fact that the IRA were targeting a British controlled Sovereign Base Area, the use of elite British troops had been given the green light by both Westminster and the Cyprus Government.

The real controversy as far as Sheen understood it was that the three IRA members who had been killed had proved to be unarmed. Plus, despite the claims about an imminent bomb threat, there were no explosives found at the scene. Although an original enquiry had judged the deaths to be lawful, there had been an international outcry, and at least one very publicised television documentary challenged the received version of events. Sheen had little doubt that the evidence which the chief would lay in front of him would confirm that the IRA members should not have been shot dead and that the conclusions of the original enquiry were flawed.

And Sheen knew why this had landed in his lap.

It had nothing to do with historic injustices. This was high politics. There were serious moves afoot behind the 27scenes to get the stalled Northern Irish parliament back in business. An investigation into the Cyprus Three would be a sweetener to encourage the main Irish republican party to play their part in getting the political system working again. No doubt something similar was in the pipeline to persuade their unionist and loyalist counterparts. And Sheen could see the logic, even the necessity, of getting the stalled parliament back on track. There was renewed violence from galvanised Dissident republicans, not to mention issues in Great Britain and Europe. The political vacuum created by the absence of the Northern Irish parliament, when added to these problems, meant there was a very real threat of a wholesale return to the violence of the Troubles. Sheen drained his pint and watched the dark clouds swirl in the dregs of his stout. He knew a man in the chief’s position had to play the game, and Sheen understood as well as any how to play along. But he’d prefer the chief tell him it straight.

The ferry was far beyond the mouth of Belfast Lough now, and the lights along the shore were hazy and indistinct. Sheen set the empty glass down and closed the chief’s message. He moved his fingers over the screen of his phone, tasting beer and diesel fumes. He opened his email and found the message from Graham Saunders that he’d received two days before. It had taken Sheen a few moments to place him. Graham Saunders, a spotty kid with a penchant for giving cheek to teachers and taking the lunch money from poor kids at their secondary school in London. Graham had never been Sheen’s mate, and in fact, as he admitted in his email, had been a bit of a wanker. He’d given Sheen a pretty hard time about 28coming from Ireland and the accent he’d still had. Sheen had not said his name or thought about the guy in all those intervening years.

Sheen scanned the message, although he’d read it more than once already. Graham said he had been in and out of prison, which Sheen was ashamed to admit didn’t surprise him. He didn’t say what for but reading between the lines Sheen guessed petty theft and burglary. He was now working as a delivery driver for a local kebab place in Holloway and driving a minicab. Graham hadn’t moved far, in every way, from his humble North London roots. But Graham Saunders had also shared a link to Belfast, just as Sheen did. And one that was a dark echo of Sheen’s own childhood trauma.

His eldest brother had been killed in a booby trap explosion in West Belfast. It had happened in 1987, a few years before Sheen’s own family had been torn apart by another bomb. Looking back, it explained a lot, the ill-concealed hatred he had shown Sheen, the anti-Irish abuse, his anger. Sheen had no idea at the time. Kids don’t. Graham ended the email with both an apology and a request.

I know I gave you a hard time, Owen, and that was wrong of me. I understand if you don’t accept it, but I want to tell you sorry. And I am not just saying it because I want your help. But I do want your help is what I am saying. I saw you in the news when I was inside, and they said you are some kind of investigator in Belfast and find the truth on things. Nobody was ever sent down for my brother’s29murder. Can you help find who done it? Like you must want to know who killed your brother? I thought Benny was so grown up, but he was just seventeen when he was taken. He was a kid.

He understood what Graham must be feeling: the anger and helplessness. They had both lost big brothers to Belfast’s vortex of violence. The loss of a blood brother, it was like a dark seam that cut through Sheen and his life in Belfast, past and present. He pressed reply and started to write, got as far as Dear Graham and then deleted the words. He watched for a few seconds while the cursor blinked at him expectantly before closing the message, his reply unwritten. He’d promised himself that there would be no more blurred lines.

In the past year Sheen had bent and broken too many rules. He’d gone after John Fryer, the lunatic former IRA man whom he believed, at that time anyway, to have murdered his brother, Kevin, in the no warning car bomb in Sailortown. In the process he had led DC Aoife McCusker into harm’s way and almost devastated her chances of building a career. More recently he’d played a dangerous game in an effort to regain Aoife’s trust and to satisfy his own desire for answers about a little boy’s death. Once again, he’d been lucky to escape with his life and the lives of his team intact. The bridges he’d burnt with colleagues in the Police Service of Northern Ireland’s Serious Crimes unit, Special Branch and MI5 would not be readily rebuilt. And now he also had the chief watching his every move.

He pocketed his phone and picked up his empty pint, his tongue ready for a refill. He would reply to Graham 30Saunders, but not now. This weekend he wanted to forget. The job, the politics, the competing requests. But even as he savoured the tingle of the stout, Sheen couldn’t shake the feeling that sometimes the past, just like our childhood, comes back and finds us, whether we’re ready or not.

CHAPTER TWO

Tom ‘Tucker’ Rodgers had a cracked ballpoint pen, an envelope, one second class stamp and no time left.

Well, that, plus a fair few regrets. The foremost of which right now being his stubborn refusal to own a computer or a mobile phone. Closely followed by the fact that the post had arrived late yesterday afternoon.

In the not so distant past Tucker had scoffed very self-righteously at pretty much every other person on the planet who felt so compelled to own an expensive mobile, especially one of the so-called ‘smart’ ones that could send an email or take a scan of a sheet of paper and whoosh it electronically to anywhere in the world. But he wasn’t scoffing from a self-righteous perch any more. He was sweating, with his back to his living room wall this Friday morning. And his old police personal protection revolver was in the pocket of his dressing gown, when he should be snoring off the effects of last night’s session. 32

Tucker pushed his glasses back up his nose and tasted the sweat that had formed on his upper lip. The bastard postie. If only he’d been on time, then Tucker would have opened the package before he had gone out yesterday and not when he stumbled through the front door at one o’clock this morning. Returned as drunk as a lord, in fact, from Roddy’s funeral. Which was ironic. Given that it was clearly Roddy who had sent him the package. And also regrettable, given the information which it contained. But to suggest that the postman had been tardy was not entirely accurate. Roddy’s funeral started at 2 p.m., but Tucker had actually gone for a few nips before, Dutch courage. Which was why he’d missed the post that had probably been delivered about the same time as usual. Either way, his head was pounding now, so much so that even the tepid light of a barely started Belfast March morning was almost too much to bear. The thought of his old drinking buddy now reduced to an urn of thin grey ash raised an unexpected lump in his throat. That and a fair dollop of booze-induced self-pity. But there was no time for laments, not when they come for you in the morning. They being whoever was in the car that Tucker had spotted slowing driving past his home more than once and who, Tucker knew in his gut, were shortly to pay him an unwelcome visit.

He’d been fond of a pint and a yarn with Roddy, not to mention the odd fishing trip over the years. He was a mate, a drinking mate. For the most part, he’d see him at the club from time to time and went over to his house for a takeaway to watch football on the odd Sunday. Tucker had always suspected that Roddy might be gay although it didn’t concern him in the slightest. Matter of fact, it was 33helpful. It meant Roddy had no wife to complain about Tucker drinking with him until they both passed out, and the craic was always pretty good. Revolving anecdotes told as new, one round merging into another, but also weeks without a meet and then friends reunited, that kind of thing. Tucker had a fair few acquaintances like him. But could the same have been said for Roddy? Given what had arrived yesterday, it would appear not. Tucker rested the back of his bald head against the welcome cool of his wallpaper and tried to think. Instead, he cursed himself again for not having a mobile, and then he cursed himself for not paying more heed to Roddy’s recent blathering at the club. His hushed, conspiratorial talk about a pension booster, nudge nudge, wink wink, a project he’d been working on for years that would pay him big bucks. The idiot must have been planning to use what was in the package to blackmail someone, someone who clearly didn’t appreciate Roddy’s entrepreneurial efforts. Finally, Tucker cursed himself for good measure for going out before the post had arrived, to soften the edges of Roddy’s poorly attended sending off. Words echoed in his head, as though by another person, one more honest and clear-sighted than he had been in the years since his early retirement from the PSNI, and certainly braver than Tucker had ever been on the matter.

I think you have a drinking problem.

Tucker made a sound that could have started life as a laugh but died as a deep sigh. Right now, that problem would need to get in line, because the booze and the hangovers were far from his only issue. He wiped a palm down the front of his dressing gown and flinched as he spotted the dark 34hatchback, creeping past the front of his house for the third time. Tucker pressed his shoulders closer to the wall and tried not to shake. He glanced at the string-bound booklet of handwritten pages bearing the neat signature of Roddy’s tidy script. That was what had been inside the package. No note, no explanation, but in a way, none needed. Thousands of words that spelt only trouble.

‘Roddy, you stupid, dead fucking wanker. What have you got me drawn into?’

But Tucker knew that his problem wasn’t ignorance. His problem was that he already knew too much.

After he’d got home last night from Roddy’s funeral Tucker had sat on the sofa with a can, changing channels on the TV, but as usual had ended up watching the news. A local story had made the headlines, that cop Owen Sheen and his historical investigations team. Something about bringing charges against a retired British squaddie for an old murder, Soldier G they’d called him. Sheen was getting pretty well known; he’d cracked a cold case a few months past, had pointed the finger of blame at establishment figures. The previous summer he’d tracked down that IRA nutcase John Fryer. Tucker had to hand it to the guy, Sheen was one of those peelers who got the job done. And he didn’t seem bothered if he made enemies or not. Tucker could drink to that, and he did. By the time he fell into bed he was plastered.

When he got up to use the toilet in the small hours, he initially thought he’d dreamt about opening a package the night before. He certainly had decided that he’d dreamt what was inside it. But the simmer of unease in his gut and sudden wakefulness at the thought had led 35him downstairs where he found the booklet on the small sofa, surrounded by empty packets of Tayto crisps. Tea in hand, he’d returned to it with that most cynical of all gazes, the dead-eyed stare of the hungover man. And though he was still half-pissed when he’d started to flick through the pages, Tucker was sober as a born-again at a Sunday service when he set it down and took a slurp of cold tea, swallowing three paracetamol with it. And hungover or not, Tucker Rodgers was a cynic no more. What Roddy had sent him looked legit. And that only made it worse. When he got up to make another brew, he also took his old revolver from the strongbox, checked that it was loaded and slipped it into his dressing gown. The weight of his old piece felt reassuring as he sat back down. Even so, Tucker’s chest felt like a panel beater was hammering dents out of his ribs from the inside. And it wasn’t just the hangover.

Roddy, a man who’d left no suicide note, had taken the time to send him this. Secret information on an IRA informer identified only by his codename, but with lots and lots of information about what he got up to fighting Special Branch’s very dirty war. Tucker lifted the booklet and fanned through the pages, seeing the same name recurring time and again.

TOPBRASS

And shortly after he had sent it, Roddy had turned up dead, hanging from his bathroom door by a belt. Cue the small talk at the service about it coming out of the blue, about how you can never really know what’s going on in someone’s head. By the time he finished his second mug the birds had started to sing, though it was still dark out. 36But Tucker’s head was beginning to lighten at least and by then he knew what he couldn’t do, which was a start. No point going to the press with this. He trusted journalists less than most of the scumbags he’d taken down over the years. Sooner or later his name would come out. No way was he going to the cop shop either. The peelers had more leaks than Northern Ireland Water. His name would end up in the papers anyway. Or something even worse would happen to him. Before the things in Roddy’s wee book could see the light of day. Tucker’s hand absently returned to his revolver, as he thought about Roddy’s manikin-like face, framed with silk and flowers, dead and unreal. Even with the make-up, the undertakers couldn’t completely mask the black bruises round his eye sockets. And then that voice spoke again, the one that was not his own, the one that said it true, like it or not.

They murdered him.

‘Fuck’s sake,’ scoffed Tucker, but the panel beater was back on the job in his ribcage. He got up, started to gather the empty crisp packets off the sofa and straighten the cushions. He lifted Roddy’s booklet and added it to the rest of the debris. He would bin it – better still, burn it – and just forget about it; pour a drink and go back to bed. Tucker paused. There was Roddy’s face again, a livid waxwork in a horror museum, ruby-cheeked and smiling-eyed no more. Roddy was a bit of a gobshite, but Tucker had liked him. And now he was dead. But the last thing he’d done was send this to Tucker. Maybe because he had been a straight enough peeler. Or maybe because the poor bastard had no one else. Tucker felt a spike of anger at this, that ebbed quickly away, leaving only the 37cold facts of his predicament. The weight of his gun in his pocket said he well knew that destroying the book would not make this go away. He glanced at the blank television screen and remembered that he’d watched the news. Remembered the report about Soldier G and the detective who had uncovered the truth, consequences be damned.

Owen Sheen.

Not a man who toed the party line or cared about shaking things up a bit. As peelers come, this Sheen was a rare breed. Tucker had walked the beat for damn near thirty years, so he knew it better than most. And he knew that a rare breed of a peeler like Sheen was just the man for the job, and maybe, was the only man he could trust.

First Tucker tried calling directory enquiries, to get Sheen’s office number. At such an early hour it was unlikely there’d be anyone working. But even so he could leave a message and find the address too. But when Tucker lifted the handset off the wall, his landline was dead. While he stood fruitlessly pressing buttons on the phone and lifting it in and out of its cradle, he spotted the car. For the first time. It was a hatchback, matt paintwork, undercoat grey and with the windows blacked out. It made a slow pass of his home before drawing away. Tucker waited by the window, keeping to the shadows, trying to keep calm. But all the while, the voice was having its say.

Someone cut the line.

He thought about Roddy, hanging from his bathroom door, his eyes blackening and tongue lolling.

They murdered him. And they’re coming for you too.

Tucker kept his head low and one eye on the window 38to the street, as he searched the downstairs, looking for anything that he could use. He was panicking but still thinking at least. He had to get Roddy’s booklet to Owen Sheen. He found one envelope, one stamp and a ballpoint pen. Seconds later the same car passed again, from the opposite direction, moving slowly, before speeding off.

Tucker ran over to the coffee table, pen in hand, poising over the envelope. He didn’t have Sheen’s address. In fact, apart from Roddy’s, there was only one other address that he knew by heart. He was about to search out his old address book, get the details of his old chief super, but then he heard the approach of a car from the dawn-quiet street, and scribbled the name and address he didn’t want to use on the side of the envelope.

His son, David, who lived in Manchester.

Good thing he didn’t need to lick the stamp, Tucker’s mouth was as dry as kindling. He crept back to his vantage beside the window, envelope and pen in hand. Seconds later the same car passed, for the third time. The sun was all but up, and the street would soon be busy.

Tick tock, Tucker.

You need to get out of here.

Tucker dived into the hallway, searching frantically until he found his house keys which he stuffed into his pocket. He stopped, looked at the envelope. It was thin and long, the kind that could contain a cheque or folded letter, much too small for the whole booklet. He hadn’t really thought this through. In fact, he wasn’t really thinking at all any more, but he was getting the hell out of the house before that car returned.

He was half out the front door when he realised he’d 39left the booklet on the coffee table. He ran in and grabbed the bound pages, stuffed them into his elasticated pyjama bottoms, securing them with a sharp tug of his dressing-gown cord. He was already out the front gate, sleety rain spitting down and stinging his bare head when he thought of his coat and hat, but he kept going. The dawn chorus echoed up and down the corridor of suburban homes. A car approached, and Tucker froze, eyes down, but it drove past without slowing. He picked up his pace, was breathing in hard rasps by the time he reached the post box another fifty yards down the street. Tucker leant one hand against its chipped, cold sombrero. That same voice now enquired why, though the object was, in fact, a cylinder, did we insist on referring to them as post boxes.

‘Ah shut the fuck up,’ he said.

He wiped the icy dew off the top of it with his sleeve and, after a quick glance up and down the street to confirm he wasn’t being observed, he loosened his dressing gown and pulled the bound pages free, setting them on top. He removed the envelope from his pocket and stared at both, one rather thick, one very thin. Stark, white headlights glared, a car approaching from the opposite direction. Tucker lowered his head and searched to see if it was the same dark hatchback, but it was too far away, the headlights too bright in the gloaming. He made himself as small as he could behind the iron pillar, put his pen between his teeth and flicked open the bound pages, found one that was blank on one side and tore it free. He waited for his brain to kick back in with something useful, anything at all. The pen started moving. 40

Dear David,

Well, good to get the formalities right. The white headlights seemed to slow, getting closer, and now Tucker could hear the approach of a second car, this one coming from behind him. Not something he’d anticipated.

He closed his eyes, gritted his teeth and strained to recall some headlines about TOPBRASS from Roddy’s book. Something that he could fit on a single page, that would give Owen Sheen a fighting chance to uncover the truth. The bastards who were right now scoping out his place had killed Roddy over this. And he would see them pay for that, but first he needed Sheen’s help. Because right now he was in deep shit, and if he didn’t get away, he would end up dead too. He opened his eyes, started to write as the wind flapped his pyjama bottoms against his legs, his face creased like a man attempting a particularly challenging bodily function.

Dear David,

They killed Roddy and now they’re coming for me.

Find DI Owen Sheen in Belfast. Only Sheen.

Tell him to look for TOPBRASS.

4th November 1981.

1st July 1984.

21st June 1986.

18th March 1987.

Trust nobody but Sheen. Watch your back.

I’m sorry.

Dad41

It was all he could manage. He stopped writing and dropped the pen. It would have to do. He folded the page, sealed it in the envelope and posted it. And then Tucker stood very still. The car with the white headlights was indeed a dark-coloured hatchback and it had stopped outside his house. Three blokes got out simultaneously from the back and passenger side. They were all dressed in dark clothing, one smaller than the others with a shaved head, one tall guy with a beard and one somewhere in between with his dark hair tied up in a small bun on top of his head. All three big-set, hard-featured. They were younger than Tucker, but not kids by any stretch. They looked like they were professional, and Tucker was glad he was not at his front door to find out what they specialised in.

Tucker watched as they approached his door. The men were partly concealed under the cover of his open front porch, but still visible from where Tucker now stood. One of them started to work on the lock. Fast, efficient. Open in under thirty seconds. Two of them slipped in, the tall one with the beard stood, his back to Tucker’s open front door, his eyes on the road and opposite windows before he too back stepped into Tucker’s home and closed the door. The dark car surged forward, coming his way. Tucker turned and started to walk. From his left, a woman’s voice.

‘Excuse me, are you OK? Are you lost?’

Tucker flinched, and then slowly turned around. The woman was half leaning out of the driver’s window of an SUV, concern etched on her features, pity too. She was driving the car he’d heard coming from behind him. The woman repeated herself, slower this time, like Tucker was soft in the head or foreign. The wind drove a cold finger 42under his bedtime clothing, found his chest, and he gave an involuntary shudder. Not a bit of wonder she was treating him like a senile old fool, that was exactly what he looked like. The hatchback was closer now, but someone, sent by a god who at least deals shit luck out in more or less equal measures, had blocked its path. A neighbour had pulled out from their parking space as the car approached along the narrow road, like only a contrary shite will. And Tucker’s neighbour didn’t look like he was ready to blink first, good lad.

The woman was talking, asking him if he knew where he lived. Perhaps the divine intervened for the second time in as many minutes, or perhaps the shock of being out in the cold wearing slippers and watching his house get invaded by three dangerous-looking bastards with dead eyes is what did it, but Tucker’s memory started working like a finely tuned machine. Something he’d heard at the club and now retrieved through the drunken curtains of countless same ending evenings.

It was an address that Roddy had told him, his beer breath on Tucker’s ear as they stood at the pisser together, telling him that it was as true as God and not to breathe a word to another soul. Tucker took a deep breath and said an address but had the presence of mind once more to name one that was a few streets off where he needed to be. Whoever had come for him would keep looking. He told the woman he’d popped out to buy a pint of milk. And then he held his breath, listening to the car horns that had started to blare from a bit further down, where the dark hatchback’s progress towards him was still gracefully blocked. The woman was out of her car. She slid open the back door 43of the people carrier, revealing a toddler strapped into a safety seat, who glanced at them, big crystal-blue eyes, full of surprise. The wee child offered Tucker a breadstick as he was helped into the seat beside her.

‘You’re all right dear. I know where you’re going, I’ll get you home,’ said the woman, who had got back into the driver’s seat and was now reversing back along the street. Tucker remained quiet, eyes fixed on the receding road ahead where he noted the stand-off had ended with the hatchback reversing at speed, stopping outside Tucker’s home. He saw the three characters emerge and get into the car. The driver had probably been tasked with driving around the block a few times, to remain inconspicuous. Which he’d abjectly failed to do. By the look on the faces of the other three, their excursion into Tucker’s residence had not exactly been a success either. The woman reversed around the corner and turned the car before setting off in the direction Tucker had named. Tucker dropped his eyes.

‘Do you have anyone at home, someone I can call?’ she asked. He could hear the concern in her voice. Absurdly, the lump had returned in his throat; the question had actually brought a prickle of tears to his eyes. ‘Maybe I should call the police,’ she said. Not a question this time. Tucker swallowed hard.

‘It’s OK,’ he said, hoping that he sounded sure, and that he would convince her. ‘I live with my son. He’s at home. He’ll give off to me for wandering off. Again,’ he lied, with a small chuckle. It seemed to do the trick, the woman returned a thin smile from the rear-view and then gave the road her full attention. The wee one thrust another soggy breadstick at Tucker, who smiled, tears in his eyes. 44

‘This is Alison,’ said the woman. Tucker said hello. ‘What’s your son’s name?’ she enquired.

The smile fell from Tucker’s face and this time he actually felt tears well up in his eyes.

‘David,’ he croaked.

‘Well, we will see David soon,’ she replied in a there-there voice.

Tucker looked out the side window at the passing details of Belfast streets beginning to wake to a new day. I hope so, thought Tucker. He’d just posted David information from a booklet that had clearly cost Roddy his life. The same booklet that had just sent Tucker running in fear of his own, dressed like Wee Willie Winkie. The hard faces of the hard men who had come to his door flashed before him and he shivered, despite the hot air that was blowing inside the car. David’s was the only address that he could have sent his message in a bottle. But now it didn’t seem like such an inspired idea at all. Tucker closed his eyes, but the tears started to fall anyway. He felt the firm edge of Roddy’s booklet dig into his skin, and he willed for his only son to keep smart and stay safe.

Because he was pretty sure he’d just put him in the line of fire.

CHAPTER THREE

Detective Constable Aoife McCusker picked up her pace as she felt the incline steepen, and let her legs do the running. She recalibrated her breathing and kept her eye on the bastard she was chasing. She was gaining on him, and she would catch him.

He was the man who had loomed over her several months before; a shotgun in his hands and murder in his eyes.

He was the psychopath who had kidnapped her adopted daughter, Ava, last summer and driven her away with a primed bomb strapped to his back.

He was the addict ex-boyfriend who had betrayed her and set her up. The man who had caused Ava to be taken away from her and almost destroyed her career.

He was every waster who had crossed their threshold when she was a little girl. The jackals who had come to prey on her vulnerable mother until she had got really sick and then, of course, they were nowhere to be seen. 46