8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: DI Owen Sheen

- Sprache: Englisch

A boy's body is found in bogland along the Irish border: a case as cold as the earth that has hidden it for so long. DI Owen Sheen has sworn to get justice for the unnamed boy and digs up links to a covert British Army unit that was tasked with creating Satanic panic in the 1970s. But when a vicious murderer begins to stalk Belfast's streets, it's clear that someone refuses to let the past remain buried. Alongside DC Aoife McCusker, who must fight to restore her professional reputation, Sheen is racing to make the connections and stop a killer against the backdrop of Northern Ireland's darkest history and uncertain future.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 519

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

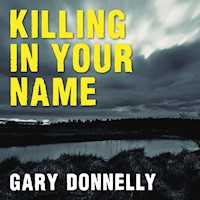

KILLING IN YOUR NAME

GARY DONNELLY

For my sisters Jennifer, Leann, Rosemary and Baby Agnes My sword and my shield

BLACK MAGIC FEAR IN TWO BORDER TOWNS

Sunday World (Northern Ireland) headline, 28th October 1973

‘In those days Israel had no king’

Judges 19:1

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Belfast, Northern Ireland February 1976

Some say we regret the things we don’t do in this life.

If only.

It was her fault. She let him slip past her unnoticed. If she’d been a little quicker, a little stronger, she could have caught him, dragged him back out the door. But she was slow and slight, and her arms were full of coats hastily shed and shoved her way.

She caught his eye though and dumped the coats. He glared back at her in a silent fury that spoke the words she’d heard from his lips many times:

‘Go away, you’re not my ma!’

Not his mother, that was true. But he had become her child in this last year, as surely as if she had borne him from her womb. Since the IRA visited death on their family and then the Catholic Church ripped apart what remained; she was the only mother he would ever have. And she was fifteen, Peter just two years younger.10

He walked into the party room to her left and joined a small group of other boys, already voluminous with drink. Peter took a can of Tennent’s, a colour image of a half-dressed woman printed on its side. It looked improbably large in his paw. He fumbled at the ring pull, finally opened the beer which foamed up. The yellow liquid ran down the side before he raised it to his mouth and drank.

Was that his first sip of beer? Yes, almost certainly. There were precious few opportunities for the boys in his home to socialise, even fewer chances of earning or stealing enough pocket money to buy a carry-out.

His eyes found her watching. He turned away with one hand jammed into his jeans pocket. From inside the party room came the swell of imbibed laughter, deep and grown-up.

There were men in there.

She’d been here to meet and greet them, had laid out the drinks table and snacks in advance of their arrival. Not for the first time: there’d been other parties like this. Some of the men were regulars, like the preacher. She’d seen him on the telly, but here he didn’t wear the white dog collar. And there was the guy with the pinstripe suit, tall and softly spoken. She’d heard the others call him ‘Counsellor’. He was usually here at the beginning. And there was the fat man. He was older, cheeks florid and always dressed in a three-piece suit. He carried a cane with a gold handle and he spoke with an accent that she couldn’t place. Something between southern Irish and an upper-crust English drawl. These men she knew, but there were many she did not; they came and went.11

What they had in common was their youth, and the power and wealth they exuded. That and the fact they were not much interested in her. She was developed enough to understand the intentions of men, and the baseness of their needs. These fellas were different. They hadn’t come to the posh house off the Lisburn Road to meet young women or for the free drinks.

They’d come for the little boys.

A cold, dead thing pressed against her bare lower arms. She flinched and yelped. A man towered over her.

‘When yer ready, love,’ he said, and shoved his black leather jacket into her receiving hands. She muttered an apology and took the coat she’d thought was a carcase. She could smell the rich cow hide, and over it, the sweet fruit gum the man was chewing. She glanced up. He was tall, so big she had to tilt her head back to see his face. Strong jaw, mean mouth, a head of flaxen blonde hair worn swept back. And grey eyes, cold as the north Atlantic coast. She’d seen photos of SS officers in books. He fit the type exactly. But not just his features, it was the cruelty in his face. Beneath the sleazy slyness of this man she could feel it, like a cold river running through him and into her. There was badness here. She recoiled, but with nowhere to go, her back met the wall and she stopped dead. He clasped her cheeks in his hand, raised her face.

‘You’re a shy one, arn ya?’ They were eye to eye. His voice was rich, but she felt the menace and knew the question needed no answer because it was really an accusation.

‘Why are you so spooked? Do you know me?’12

She didn’t, but she knew that he was different from the others, rougher. His coat was leather, not tweed or camel hair. His accent had the twang and truncation of the Belfast streets.

She tried for a smile, not easy. He examined her like a new-found species, the grey of his eyes now almost fully black. Just like Jaws from the film she’d sneaked in to see at the ABC on Great Victoria Street. His eyes were exactly the same: black and empty. She glanced away and he followed her eyes.

Her baby brother, animated now, was talking to another boy maybe a year or so older, their faces visibly flushed with the drink. The older boy and Peter walked out of frame. Counsellor emerged and strode their way. His smile was full of affable welcome, but his eyes showed calculated concern as he took in her predicament.

‘Sure, it’s grand to see you,’ he said, extended his arm. The move worked. The man with the black eyes released her face and they shook hands.

‘A’reet,’ he replied. Counsellor handed her two folded pound notes. Her wages, and her signal to go.

She took her payment, fingers trembling, mumbled a thanks. But Counsellor had already turned his back and was walking his guest towards the party room. Counsellor was big, but even at that, not quite as tall as the man with black, soulless eyes. She took a hanger from the rail in the cloakroom beneath the stairs and hung the black-eyed man’s coat up. A hard weight, inside pocket, knocked her hand. She reached her fingers into the jacket, felt cold steel. Slowly, she pulled out a butterfly knife, long as her hand. She put it back, but instead of leaving she walked slowly to 13the party room, the noise and the stink of tobacco smoke becoming thicker as she approached.

She peeped round the doorway. Groups of men with boys and youths, all drinking, most smoking, voices animated. The fat, old man with the funny accent was in an armchair in the corner, near the roaring open fire. A boy was seated on one of his boiled-egg thighs and the man’s plump hand was rested on one of the boy’s knees. She searched from face to face, looking for Peter. She spotted him, all alone again.

‘Peter! I’m taking you home,’ she shouted and started towards him—

An iron grip on her upper arm, hard enough to make her shriek, but nobody heard it. She turned to see Counsellor’s flushed face in her own, his eyes wide and angry. She tried to pull away, but it was impossible; he was so strong, and she was so weak.

‘Out!’ he snarled, small globs of his spittle hitting her mouth as he said the words. Then she was dragged off, helpless to resist. She stole a final look at the room. The big, black eyed shark was on the move, headed to where her little brother stood alone.

Counsellor opened the front door and shoved her out hard enough to send her sprawling down the front steps and to her knees. Her threadbare coat followed and snagged in a big shrub.

‘You’re sacked, you stupid little bitch. Don’t come back,’ he hissed, casting a furtive look both ways. The halogen-lit street was the model of silent suburbia and answered not. He closed the front door with a rattle of the knocker. She watched first the lantern light over the small 14porch extinguish and then the hallway light. She got up, warmth and pain from her knees, thought about chucking a rock through the front window. Instead, she pulled her wretched coat off the bush and shuffled to the front gate, tears coursing down her face.

Peter was in there, and there was nothing she could do about it. She was just a girl, a weak nobody. And worst of all, she’d let him in. That man, who in her heart she knew was ten times, a hundred times worse than all the rest; she’d opened the door and let that evil man in. She reached into her blouse pocket where she’d put the precious pound notes. She scrunched the currency into a ball, raised her hand to throw it away and then she stopped.

Because this wasn’t the movies, and this year she’d almost saved enough for the fare to England, enough for both of them. She returned the money to her pocket. She could feel the rage and the shame and the hopelessness scorch her throat and settle deep down in her fledgling breast where it had already started to burn.

She shuffled off, the wind slicing at her tear-wet face. When she closed her eyes all she could see was the great white predator on a course for her baby brother. She raised her face to the cold heavens and screamed, and her cry was swallowed up by the black Belfast night.

PART ONE

SKELETONS OF SOCIETY

CHAPTER ONE

Belfast, Northern Ireland, present day Monday 17th December

The dead are silent in their graves, but at night they speak to Owen Sheen.

His brother Kevin, telling him to run after the football as it skimmed and bounced down the gloaming Sailortown street in Belfast so many years before, seconds before a car bomb exploded and obliterated him. He asks when Sheen will come visit him; tend his grave in Milltown Cemetery. He tells him that it’s a disgrace; overgrown and forgotten.

John Fryer, the escaped IRA lunatic he’d hunted down last summer, speaks. His words, as always, an answer to Sheen’s question when he finally cornered him: Did you kill my brother?

Maybe I did. I did so much but don’t remember now.

Sheen had squeezed the trigger anyway. His own ineptitude with firearms was all that had stopped him from murdering Fryer. But the bullet he never shot had put a hole in his personal code; he’d killed a part of himself when he 18tried to shoot that unarmed man. He drags deep on the hot stub of his roll-up and winces at the burn, crushes it. The smoking is new, but it caught hold fast. This was John Fryer’s lifetime addiction, and unless he quit, it would become his. Another voice speaks up, this one faint and far-off, and this one is worst of all.

What’s my name, Owen Sheen? What’s my name?

That’s the voice of the boy.

His team had searched the bogland of County Monaghan and found the remains of the youth, Jimmy McKenna was his name, murdered and Disappeared there long ago by John Fryer. But no sooner had McKenna been found than another shout echoed across the drained bog. Another shout, and against all odds it was another body. It was decapitated, mutilated and buried in a wooden cask. And this boy was younger. But the child with no name was a chance discovery and was officially no business of Owen Sheen. As they were over the border in the Irish Republic, the Gardaí took control, and Sheen had walked away. But the boy had found him, time and again.

‘What you going to do about it, Sheen?’ he asked the empty room.

If the past three months were anything to go on, damn all was the answer. The Northern Ireland Assembly had stalled, and with it, the administrative arm of the Northern Ireland Office that oversaw his work with the Police Service of Northern Ireland was effectively out of action. Since locating and returning the remains of Jimmy McKenna, he and his team had been put out to pasture. Paid to wait in limbo for the politicians to learn how to play nice.

He checked the digital glow of his bedside clock. It 19was just shy of 6.30 a.m. and outside his Laganside loft apartment he could hear the stirrings of another working week beginning for some. Sheen got up; he’d sat around for long enough. He scraped his car keys and phone off the table by the door. He checked for recent messages or missed calls. But it was one name he hoped to see. He had not spoken to Aoife McCusker in person since the day he had visited her in hospital in August. Not spoken at all since their stilted phone call about three months ago. A new distance and a thus far failed promise from him to call again. And, of course, not a whisper from Aoife. He pocketed his phone, glided down the stairs. She blamed him, probably fairly, for what had befallen her since the summer. But this week would be different; by the end of it he’d have got in touch, for better or worse.

He navigated the side streets and the slip roads, and, once on the M1, he let the Vauxhall Insignia Turbo go, driving south-west. Sheen was headed for the western edge of County Monaghan, a part of the Irish Republic that extended north and was flanked by Northern Ireland on two sides. The bogland, where he’d spent most of August excavating, was just across Monaghan’s western border. He let his hands and feet do the driving. God knows they knew the way. At Dungannon the motorway disappeared, like it had given up as impossible its attempt to extend modernity into the wilds of County Armagh and south Tyrone. Sheen adjusted his speed, looked out for farmers in tractors, and chewed over the names of the approaching townships as he ate up the miles: Aughnacloy, ford of the stone; Clogher, meaning stony place; Fivemiletown, originally known as Baile na Lorgan, meaning townland of the long ridge.20

The gradient steepened and the relief changed from arable land to upland bog. If he kept going he would reach the village of Welshtown, the last settlement on the Northern Ireland side of the border in County Tyrone, and the place where he and his team had been based in August. Beyond it, the land changed seamlessly into County Monaghan, and the Irish Republic. The lonely desolation of Coleman’s bog was all that awaited the wanderer from here to where the land dropped once more, leading eventually into Monaghan town. Sheen drove on, hardly adjusting his speed, beams on full. There’d been a lot of talk about the threat of a hard border, but talk was all it would ever be in this wild land. The idea of a border was as meaningless here now as it had been when they first drew a line in the map. Sheen pulled in and stopped at a passing place.

He got out, breathed in the damp morning air and listened to the rustling sounds of the darkness which greeted him, as he changed his shoes for the stout hiking boots he kept on a plastic sheet in his boot, and pulled on the thermal-lined waterproof rolled up beside them. The blue beanie hat he kept in the pocket was still there and he pulled it down over his ears. He felt in the other pocket of the jacket and found the snug shaft of the powerful little Maglite. He turned it on and off, and in the light he saw the short-handle shovel he had carried with him every day while searching for the body of the young man, Jimmy McKenna. He had rarely used it on the dig, the main forensic work had been carried out by excavation experts or heavy-duty earth movers, but like the leather Brief of St Anthony he had round his neck, a gift from Aoife McCusker, it was a talisman. And it had worked. 21He unlatched the silver stainless steel gate by the road and closed it again behind him before starting up the dirt track.

Twenty minutes later he stopped. The thin path he’d been on had faded away and the land dissolved into an expanse of waterlogged swamp. Somewhere close by was where they had finally unearthed the body of McKenna. He veered due south, searching for the place where the second cry of ‘Body found!’ had been raised, searching for the marker he needed. Sheen squinted in the half-light at the excavation trenches his teams had made in the peat bog adjacent. The metal spikes they had used to tape off the area were still impaled waist height in the earth, though they should have been removed. He stopped at the dead-looking tree, its blackened arms stretched from west to east, and jumped down the ridge to reach its exposed roots. The cavity was still visible under its trunk where the cask containing the body had been discovered.

He could see rust deposits where the metal bands of the cask had been, and the vague impression of the wood in the sheltered core of the cave. He reached into the cavity, dug his hand into the cold, wet peat, felt it embed under his nails and cool his blood and bones instantly. He took out a handful and raised it to his face, breathed its rich, nearly disinfectant odour. He tossed the loose earth into the hole. Someone had dumped a child here, to cover unspeakable things. Sheen stood up and clapped his hands clean of earth. This was not his manor. Technically, not even his country. But he’d discovered the body and that made it his responsibility; he would never be able to let it go.

‘I found you and now I am going to find out who did this to you,’ said Sheen. A muffled pop then another in quick 22succession some distance away, coming from the east. The shotgun fired again, both barrels. Sheen scanned the horizon but couldn’t see a soul. He moved off and then saw a rabbit, followed by another bouncing from one grassy knoll to another before both disappeared into the earth. The guns barked again as Sheen trudged back across the border. He wasn’t the only person out hunting at dawn after all.

CHAPTER TWO

Sheen bit into the soft, flour-dusted soda farl, still warm from the oven. Melted butter escaped, a rich contrast to the naturally acerbic taste of the bread. Three or four big bites and it was gone. He dabbed his mouth with the paper bag. Maureen set his tea on the counter, plus two fat pancakes that he’d not ordered.

‘Those are on the house. You’ve ailed,’ she said. Maureen had not changed a bit since he was last here at the end of the summer; she still looked somewhere between eighty and National Trust protected status. Stick-thin with blue rinse hair under a netted hat; she had a puckered smoker’s mouth and teeth too perfect and too white to be anything but part-time occupants in her head.

Sheen thanked her without comment. The haggard-looking man who’d stared back from the mirror over his bathroom sink this morning was dark-eyed and a bit too thin. The overall look wasn’t helped by the thick rash of stubble approaching 24beard status. A bad time in life to first grow one, apparently; there was lots of grey and, alarmingly, more than a little ginger too. Sheen wasn’t sure which was worse. He attacked the pancakes and moved out of the way for the next in line. Mostly they were thick-booted farmhands and municipal labourers wearing high-visibility coats, loading up on calories for the day ahead. Maureen’s hands set to work making the next order, but she spoke to Sheen.

‘Not seen your face for a while,’ she said, and twirled a paper bag until it sealed closed with two pointed Doberman ears.

‘Been busy. Back in Belfast,’ he said.

Maureen fixed him with a stare. ‘But you’re back in Welshtown today all the same. Think you’ll be busy in these parts again?’ she asked. Maureen had made him welcome and never pried about his business while they were on the dig, which he’d appreciated. His team had given her good trade in return. But Sheen had read the hostility and resentment on the faces of the locals. The discovery of McKenna’s body, albeit just across the border in County Monaghan, had brought Welshtown an unwanted notoriety. Like the little town of Lockerbie in Scotland, one bad event from the past had changed it permanently. He set the money he owed her on the counter.

‘No, just woke up and knew that nothing but Maureen’s would do,’ he said.

‘Smooth-talking bastard,’ commented Maureen.

Sheen had polished off the pancakes, took a slurp of the tea, strong and hot, so good.

‘Same again?’ said Maureen.25

‘They call people like you feeders, Maureen. I’m done, thanks,’ he said.

She cocked her chin to the wall behind Sheen. ‘Our boys are having some season,’ she said.

Sheen glanced up at a framed clipping from a sports page. It was the Irish News, the Belfast daily paper. maguire plays it sweetly for the harps. Beneath the headline was a muscle-roped young man wearing a gold and green jersey captured mid sprint, hurley extended with a ball apparently glued to the end.

‘Welshtown Harps?’ asked Sheen. Local Gaelic athletic club.

‘That was from the quarter final a couple of months back. This week’s the semi against Monaghan.’ Sheen could hear the disdain in her voice at the mention of the rivals.

‘Good luck to them,’ said Sheen.

Maureen folded her arms and nodded, looked grim but clearly happy with Sheen’s reply. An old gent tapped his cane on the floor a few times and nodded his agreement. He had a net of broken veins over the tops of his cheeks and Sheen could hear the wheeze of his breathing as well as a faint smell of menthol coming off him. But there was also a packet of battered-looking filterless cigarettes protruding from his fleece pocket. For him a tap was easier than spoken agreement. Real men saved their last breath for a smoke. This would be him some day unless he, as his Belfast colleagues liked to put it, caught himself on and quit the stupidity of smoking while he still had time. Nonetheless, having drained his tea, the glimpse of tobacco had sent his hand in search of his own. He jammed it into his jacket pocket. Then something else caught his eye.26

… satanic panic

It was half a headline from a story that was featured on the opposite page of the cutting, much of it missing. Sheen searched for the date, noted that it was from two months previous. He recalled that about that time there had been a scheduled release of Ministry of Defence records pertaining to Northern Ireland, a glut of material that had previously been withheld and dating back up to forty-five years. A number of newspapers had run stories on the declassified files, and he’d read a few with interest. This was almost certainly one of them, but Sheen had missed it.

He scanned the text, felt his heart quicken as he pieced together the broken sentences and extracted the meaning. An undercover British Army unit engaged in psych ops to falsely link paramilitary groups with black magic and devil worship. Black candles and inverted crucifixes in country lanes; fake news ’70s style. But Sheen had found a child’s body, probably from the same time, a child who had been ritualistically murdered, but for real. He noted the name of the journalist who’d penned it: Dermot Fahey.

‘You read this?’ he asked Maureen.

The old boy answered him. ‘I remember it,’ he said hoarsely.

‘Seriously? Black magic and bogeymen?’ asked Sheen.

‘It went on, boy,’ he replied, and beckoned Sheen outside where he sparked up a tab with yellow-tipped fingers. The blue smoke wafted Sheen’s way. ‘Thon bastards killed my brother’s donkey in the fields. Cut the poor creature’s head clean aff,’ he said.

‘Animals were sacrificed?’ asked Sheen.27

‘Certainly. Animals destroyed, and worse, cut to ribbons, tortured,’ he said, and then broke into a coughing fit. But what if decapitating and mutilating animals was not where this story ended? What if someone involved got a taste for the real thing, or found a way to practise even darker acts, under the cloak of such secrecy? Like torturing and killing a child, for instance?

‘Do you know if that article mentioned any names, people who might have been involved?’ asked Sheen.

The old man shrugged mid cough.

Maureen spoke up from the counter. The breakfast rush was over; the small shop was quiet and empty. ‘The soldiers were based at Aughnacloy army base. It’s gone now,’ she said. Aughnacloy made sense. Close to the border, easy access to farms and towns, not too far from Belfast. But also close to Welshtown and Coleman’s bog too, a place where bad men buried dark deeds. Sheen wanted to speak to the journalist, Fahey. But first he needed to have a proper look at the boy’s body. It wouldn’t be easy, but he had a plan. He thanked Maureen and said goodbye.

‘Hope the farl was worth the drive,’ she said.

He told her it was as good as ever. ‘Hope the home team win,’ added Sheen.

‘Bit of luck and a lot of prayer,’ she replied, and as Sheen drove out of Welshtown he reflected that that was probably what he needed.

CHAPTER THREE

After leaving Welshtown, Sheen pulled in, careful not to veer too far to the left and get bogged down. He scrolled through the contact list on his phone, found Pixie McQuillan’s name and called her. Pixie was a sergeant with An Garda Síochána, the Republic of Ireland’s National Police Service. She’d joined Sheen and his team as they excavated over the border, searching for the body of Jimmy McKenna. Pixie’s presence had been a token of co-operation from the Gardaí, but also a set of ears and eyes for her superiors. Sheen and his team were under no obligation to report to Dublin.

‘Owen Sheen,’ said Pixie, sounding sleepy. Sheen checked the clock, just gone 8.30 a.m. If she’d been on a night shift, he had probably woken her. ‘I’ve woke up with you in my bed after all,’ she teased. Sheen winced. Three weeks into the dig and a few pints of stout later, Sheen had made a pass. Clumsy and badly timed; Pixie was just about to start showing him photos of her girlfriend and their two 29kids. Awkward, and, though she’d laughed it off, she’d made sure Sheen hadn’t forgotten it. In retrospect her fine features and blonde hair gave Pixie a likeness to someone else, maybe the person Sheen had really wanted to be with after a few drinks on an August evening. He ignored her jibe, opted for the direct approach.

‘Pixie, do you know where they took the body? The one in the cask, from the bog?’ said Sheen. No immediate reply but the sound of splashing water. Pixie had overseen the body after one of Sheen’s guys had made the discovery.

‘Monaghan General,’ she said. Sheen nodded, it made sense. Monaghan was the closest hospital of any size and probably had a mortuary and cold storage. The hospital was south of the border, where Sheen was a civilian.

‘It’s not even active, you know. Straight to a cold case file until some retiree with spare time gets pulled in to look into it,’ she said, voice free from her slumber and, Sheen noted with some encouragement, a bit of an edge. Pixie had not forgotten the body.

‘Autopsy?’

‘Aye, but routine,’ she said.

Sheen gritted his teeth, and slowly shook his head. In cases like this one, where a crime was clearly involved, a forensic autopsy rather than a routine one was standard. Primarily because the increased level of scrutiny often yielded evidence for the criminal investigation. But the investigation into this child’s awful death had obviously ended before it had begun.

‘You’re kidding me,’ said Sheen flatly.

‘Budget,’ she replied, which at least partly made sense. A forensic cost a lot more than a routine one. But Pixie’s 30meaning was more far-reaching than the cost of the medical examination. ‘Powers that be see it as a Northern case, Troubles’ legacy. No one’s pushing for results; the media’s been kept at bay. We’ve got enough on our plate to keep the Gardaí stretched to the limit down here,’ she explained.

All of which meant the case was as cold as the earth that had kept the body hidden for so long. Without the benefit of a forensic report to use, Sheen was at a disadvantage, but it didn’t mean there was no value in seeing the body. And just because her superiors didn’t care, it did not mean Pixie had given up.

‘Can you help me get access to the body?’

‘This official, Sheen?’ she asked. Pixie might be sympathetic to an investigation, but he wanted to insulate her from any blowback. The direct approach had its limits.

‘Far as anyone who comes asking later, I’m telling you it is. I’ll take the rap. My word,’ he offered.

She laughed. ‘Jesus, Sheen, could you be any more melodramatic? I have stuff to do this morning, but I’ll be done by one. Meet me at Monaghan General at one-thirty,’ she said.

Sheen thanked her and ended the call.

Sheen’s Internet connection was weak and his search was slow work, but eventually he found the service he needed, plus one or two other details he was interested in. Microfilm archives were located at the library in Clones, a town south-west of Monaghan, right on the border with County Fermanagh and Northern Ireland. He tapped the address into the car’s GPS. Thirty minutes away, but this was Monday morning. He put the Sig in gear and hit shuffle on his music player. The Beach Boys ‘Good Vibrations’ twirled 31out from the speakers, and he welcomed it gratefully.

It was shortly after 9.30 a.m. when he pulled into a parking space outside Clones Library. Not what he’d expected. It was an impressive modernist structure; interlinked concrete blocks, tinted glass window walls, clean lines. It reminded Sheen of the millionaire mansions whose lines and corners peeked from behind security gates and high fences on the hills leading from Highgate down into Hampstead Heath in London. Sheen entered and the automatic doors sealed behind him, the hush of the library settled. Mostly vacant seats and tables, but a few teenagers had already bagged window stalls that ran along one wall. They were plugged into white headphones with fat textbooks, coloured study cards and segregated folders of notes spread before them. The reception desk was empty.

He picked up an information leaflet and saw that the microfilm readers and printers were available on Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday only. Not looking good.

‘Can I assist you?’ Sheen looked up. A woman, mid twenties, was now behind the counter. She had dark hair politely pinned off a full face which was pale apart from the rose of her cheeks. Her conservative cardigan and blouse combo jarred with the chrome eyebrow bar and the coloured petal of a tattooed flower that was part of a much larger piece concealed under her sleeve.

‘Hope so,’ replied Sheen. He reached into his jacket and flipped open his PSNI warrant card. She glanced at his card, and then met his eyes again.

‘Are you from London?’ she said.

‘Spot on. DI Sheen. I’m with the PSNI, though I came 32from the Met Police,’ he said, his ungainly backstory feeling like a right mouthful. But better to keep talking and make it personal. He had a favour to ask and if he offered a bit of background, she might be more inclined to help him out.

‘I’m Lucy. Are you, like, on official business?’ she replied.

‘Thing is, Lucy,’ said Sheen confidentially, ‘I am, and I’m on the clock. I’m looking for something that might be stored on microfilm here,’ he said.

‘Access hours for the readers and printers is Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday only,’ she said.

‘Which I have just found out, after travelling all the way from Belfast this morning,’ said Sheen, holding up the information leaflet between them.

‘We need another member of staff present, someone to run and fetch. Plus, people need to be overseen when using the equipment,’ she said.

‘Can you make an exception?’ asked Sheen.

‘You asking me to break the rules, Mr Policeman Sheen?’ she asked. A silver tongue stud flashed into view, the metal bead clasped fleetingly between her front teeth. Sheen actually felt himself redden. Ridiculous. He was tired. Too late to stop, as Van Morrison once sang. He leant his elbows on the counter.

‘I think I am,’ he said. She glanced over at the students whose backs were still arched over their work, and then beckoned Sheen with a twitch of her eyebrow. She walked straight into a room which was pitch-black. He stayed at the open door as the overhead LED spots came to life. Lucy was already standing halfway across a room where three plastic-covered stations waited against the far wall, a large printer adjacent.33

‘Movement activated lights. Come on in, I won’t bite you,’ she said.

Sheen entered the room, not entirely convinced.

‘Now what exactly are you after?’ she asked.

‘Old newspaper editions, but I’m not sure which,’ he said.

She nodded in response, her tongue bolt on display again but business mode now.

‘Is there a local paper that serves both sides of the border, maybe covering Monaghan, south Armagh, Fermanagh?’ He told her he was interested in the mid seventies onwards, but not what he was interested in finding. Not that he really held much hope of finding anything of great value. But the fact was that a newspaper article had given him an unexpected lead, so why not do a bit more digging while he was in the neighbourhood? Made more sense than driving all the way back to Belfast, and he had a few hours to kill before his planned meeting with Pixie at Monaghan General. Lucy took a few seconds to consider his needs.

‘I’d start with the Northern Standard. It’s well established so we have back copies from those dates, and well before that. Circulation covers the area you just listed, bit more besides,’ she said.

‘Is the Northern Standard daily or weekly?’ he enquired.

‘Weekly.’ Good news. This meant fewer copies and more chance of picking out patterns across a period of time. Sheen gave her the range of years he wanted.

‘Was there anything else?’ she asked, a smile playing on her lips. Sheen wasn’t sure if they were back on tease mode, but if so, he had little time to play the game just now.

Sheen shook his head, but then thought of the article on Maureen’s wall in Welshtown. He wanted to read the 34piece in full to pick up any details he might have missed.

‘Do you stock recent copies of the Irish News?’ he asked. She nodded, told him there was a daily copy in the reading room on the rack.

‘I need to see an article from about two months ago,’ he said.

‘We keep a six-month paper archive, then they get moved into microfilm,’ she replied. Sheen gave her the date of the edition he needed. She’d made it to the door when he called after her.

‘Don’t suppose there’s any danger of a coffee?’ he asked.

The tongue bolt flashed and so did her smile. ‘No hot drinks permitted in the microfilm room, bottles of water only,’ she said.

Sheen gave her a small salute. ‘The rules,’ he said.

CHAPTER FOUR

Ten minutes later Sheen was scrolling through his first batch of weekly microfilm editions of the Northern Standard, a steaming mug of black coffee next to him and two remaining chocolate digestives left on his plate. The investigative report he had read on Maureen’s wall in Welshtown had said the covert army unit were most active between 1974 and 1976. This made sense. While Sheen had checked online for library services and opening times, he had also found a macabre ready reckoner for the number of people killed in Northern Ireland’s Troubles across all years, each total helpfully broken down according to types of victims: ‘Police/Army’, ‘Paramilitary’, and ‘Civilian’.

Apart from 1972, by far the single darkest year of the conflict, the years between 1974–6 had the worst run of violence that was seen over the near thirty-year period of the Troubles. Like 1972, these years were infamous because proportionally more innocent civilians died in comparison 36with active combatants. Sheen could read the story behind the numbers. The country had been sliding headlong into all-out anarchy. If there was a time for disinformation and black propaganda to alienate the population from paramilitaries, this was it. Question was, did it begin and end with scare tactics and make-believe?

Sheen had started with 1973, just to be sure. He was just about getting the hang of the speed control by the time he completed the year, but saw nothing that made him pause and print. Still, even though he’d readied himself, the constant reports of violence from all sides were truly frightening. He mentally worked out what age his parents had been. Both were Belfast-based, not yet married at this time, and living on opposite sides of the divide. Too late to ask either of them what their lives had been like in those years. Sheen was aware that a short time after marrying they had looked into going to live in Australia. Sheen changed the reel and started on 1974 and pretty soon could see why newly-weds would think of emigrating.

There was death and destruction in every edition, a war played out in slow motion. Any single event transplanted to modern times would dominate headline news for weeks on end, but in this deep valley, one atrocity merged into the next: the IRA attacking off-duty police and soldiers, loyalists murdering innocent Catholics, tit following tat. But even in times of violence and chaos, some atrocities can still stand out. On 17th May of that year, no warning car bombs were detonated during rush hour in Dublin and Monaghan, killing thirty-four (including an unborn child) and injuring hundreds more. It was the single deadliest attack of the Troubles and it had gone unclaimed at the time.37

Sheen pushed his chair back, took a mouth full of cold coffee, and swallowed it with a grimace. He checked his phone, just gone 11.30 a.m. If he skipped lunch then he’d make his appointment at the mortuary with Pixie in Monaghan, but he needed to pick up his pace. He set to work, and soon paused to study a story. Local farmers had complained about the British Army illegally crossing the border through their land, damaging outbuildings and fences during clandestine searches in the middle of the night. He scrolled on, his eyes started to glaze, his mind wandered to thoughts of a lunch break after all.

He stopped and removed his hand from the forward button like he’d just taken a mains voltage kick.

Sheen slowly reversed the direction, eyes alert and focused again, searching for what he thought he had seen. He stopped, took his finger off the cursor and read the headline.

livestock destroyed in dead of night

‘OK then,’ he said softly. Pat Ney, Monaghan livestock farmer, had found two of his weaning calves missing from the barn and dead in the field, their throats cut. The carcases of the animals had been laid out with their heads touching. This was the second instance of what the article described as ‘livestock destruction’ in as many months. Sheen drummed the tabletop with his fingers, then pressed print, heard the chunky Laserjet whirl to life and efficiently deposit a copy of the story in the tray. His alertness sparked now, he moved meticulously and speedily through the weeks and months, drawing 1974 to a close. He quickly replaced it with 1975. Almost immediately, he got a direct hit.

evidence of black mass found38

Beneath the headline was a black and white photograph of what looked like upended tin pots with dried grass protruding from one. In the background was the burnt out remains of what had been a thick, black candle. He printed and continued but not for long. He stopped again in March 1975.

black magic fear in two border towns

This report had made the front page, contained more photographs and verbal testimonies from a number of frightened witnesses whose farm animals and pets had gone missing, some found horrifically mutilated. The report claimed that a British Army patrol had stumbled across a black magic ceremony being held in the foundations of an abandoned castle close to the border. The suspects managed to get away, Sheen was not surprised to learn.

Sheen studied a photograph taken in the bowels of the castle ruins. An inverted pentagram was enclosed inside a circle, both traced in what looked like salt. The gutted remains of thick black candles marked the apex points, and symbols had been shaped, again in salt, adjacent to each one. But right at the heart of the pentagram, and much larger and more prominent than the rest, was another symbol. Sheen at first thought it was an inverted cross, but after drawing nearer the image saw it was more like a sword, with a half-moon arching from its blade. Whatever it was, it meant something to those responsible for creating this superstitious panic, which meant it could well be important for Sheen’s investigation. He had worked countless cases in which small details like this ended up turning cases, and more often than not they’d been staring detectives in the face from the murder file 39all along. Sheen pressed print and took out his phone. He searched the details of the symbol and felt a flutter of exhilaration and satisfaction when he read the first result.

‘Saturn,’ he said.

He scrolled quickly through the information. The second largest planet in the solar system was also a central symbol of the occult and astrology, associated with the harvest and the night. What he’d mistaken for a half-moon was in fact a scythe, the origins of the popular image of the grim reaper. Whoever had traced the symbol in salt had really done their homework. Or had really believed in what they were up to. Sheen clicked open the next image.

‘Bloody hell,’ he whispered. It was the 1636 painting Saturn Devouring His Son by the Flemish artist, Peter Paul Rubens. Sheen stared at it; Saturn in human form, old and grey, devouring one of his children. Sheen emailed himself the link, certain that this was significant, and returned his attention to the microfilm. He was dying for another brew and a smoke.

He forged on, got partway through 1976 when he checked the time on his phone and saw a missed call from Pixie. It had just gone 1 p.m. Sheen cursed silently, sent her a text to say he was on his way and went back to flying through weekly news stories, already aware he was growing numb, his alertness all but blunted. He stopped.

horrific donkey sacrifice terrifies border community

The image which accompanied the piece was the most graphic he’d seen yet. The carcase of a donkey, on its side in a field, its head hacked off and resting some feet away, its eyes gouged out. An inverted cross had been carved 40into the animal’s back. He scanned the story, found much of the same outrage and dismay as in previous articles, but with one exception. He read a quote from an unnamed local woman:

‘It’s just a matter of time before these evil people go for a human sacrifice. It’s what they really want.’

Sheen pressed print, continued to scan, but found nothing more as the hot summer of 1976 faded to early winter. By the last week of November, he was ready to call time when he saw it.

local lad missing: fears mount

‘Jesus wept,’ whispered Sheen. He’d expected some reports of animal destruction, but not this. He read the article, digested it quickly and sat back.

Declan O’Rawe, aged twelve, had been on his bike travelling home from a friend’s farmhouse near Terrytole, but never made it home. Sheen closed his eyes and racked his mind to remember where he’d heard that name before. He saw it, as it flashed past him on a small sign at the side of the B road he had driven from Welshtown to get here. Close enough to where the body in the bog had been discovered. His heart picked up, excitement ballooning in his chest. If Declan O’Rawe was a missing child who had never turned up, a DNA check with any remaining family could quickly identify the boy’s body. Sheen hit scroll, approached the end of 1976. No more mention of the boy until the first week of December when his bicycle was uncovered by a farmer from a hedgerow in Armagh, over the county line and over the Irish border. Sheen slowed as he approached the end of the year, more certain now he was onto a winner, and then stopped when he found Declan.41

O’Rawe’s body had been found burned, dismembered and bearing signs of torture near the River Lagan in Belfast. He had been wrapped in a blanket and dumped on waste ground.

O’Rawe was not his body after all, and the facts did not fit. This boy had been dumped and probably murdered in Belfast. His death had been just one more that made up the horrific civilian death toll in the mid 1970s, many of them picked off streets, taken away and tortured before being dumped. Then again, he’d come from Monaghan, fairly close to where they’d discovered the boy’s body in the bog. But right now, Sheen couldn’t see the woods, let alone the trees. One last time he pressed print.

‘Sheen, you all right?’ It was Lucy, standing by his side, a newspaper in hand. Sheen turned and stared at her mutely, suddenly aware that no, he probably wasn’t. His detour into the 1970s had left him shaken and sickened. It was as though the ordinary rules of civilised society had been tossed out the window and murderers and sociopaths had enjoyed a free hand. He’d read somewhere that at the height of the Troubles, the psychiatric ward that treated aggressive psychopaths in Belfast had to close down because of a lack of patients. If the news reports that Sheen had just scanned through were anything to go on, it was because they were running wild on the streets.

‘Fine,’ he said, with a weak smile.

‘And forgetful. You wanted this Irish News back issue. Plus you owe me for those printouts,’ she said, handing Sheen the newspaper. Sheen took the paper, found the article and asked if he could get a photocopy. Lucy brought it back a few moments later.42

‘How much do I owe you?’ he asked.

‘Three euros per microfilm, plus fifty cents for the photocopy. Unless you’re able to sign it off as official state business, in which case it’s free,’ she said. Sheen handed her his credit card which she charged at the reception desk. At least the coffee and biscuits were on the house.

As Sheen exited the sealed world of the library, the gusting wind knocked him from one side, and he just about managed to clasp his printed pages to his chest as he texted Pixie to say he’d been a bit delayed but was en route.

As he headed off the N54 for Monaghan he thought again about the small sign he’d passed for Terrytole, dead children and the words of warning from a farmer’s wife too terrified to give her name in 1976.

So far Sheen had two bodies, ritual and sacrilege. In a world where murder and destruction had become a background noise, it seemed that evil men had been free to indulge their darkest fantasies and get away with it.

But now Sheen was on their case.

CHAPTER FIVE

Pixie was waiting for Sheen at the entrance to Monaghan General Hospital. They clapped hands, made a fist and then she took him by surprise and drew him in for a hug and a slap on the back of the shoulders. Sheen reciprocated, but for him the gesture felt alien, his embrace ill practised and stiff.

Pixie led the way to the wide lifts which, after an almost imperceptible descent opened to a low-lit basement corridor painted an institutional light green. The hospital smell was thicker here; Sheen could taste that heavy combination of antiseptic, like warm pitch tar, and stale, recycled air.

‘This is it,’ said Pixie.

Sheen noted that some of the healthy colour had seeped from her cheeks. He pushed open one of the hinged rubber doors and they entered a brightly lit tiled room, its whiteness glaring and brilliant in comparison 44to the murk of the corridor. A man wearing a white coat stopped what he was doing at an open metal tray where an array of steel instruments was spread. His hair was dark and rich, but on the retreat, his tailored moustache flecked with white. He greeted the strangers in his domain with a smile.

‘Can I help you?’ he asked.

Pixie introduced them both and showed her identification. She quickly explained what they had come to see, asked if the body was still in the mortuary. The attendant introduced himself as Michael Mulligan and they shook hands.

‘Yes, we are still in possession of the remains. Pending identification, and investigation, I presume,’ he said.

‘Did the autopsy take place here, Michael?’ asked Sheen. He could see the raised steel table across the room, the drainage channels feeding into the plughole in the floor.

‘That’s correct, sir, yes. The acting deputy state pathologist was sent up from Dublin,’ he replied.

Sheen quickly tried to assimilate the jargon. In Sheen’s experience, the bigger the case, the better established the pathologist. He didn’t need inset training to know that an acting deputy being sent up from Dublin meant a case wasn’t a top priority.

He turned to Pixie. ‘Were you present?’ he asked. She shook her head. Fair enough, thought Sheen, a senior investigating officer (SIO) sometimes was, in the way Sheen himself had been invited and attended the autopsy of Jimmy McKenna in Belfast. But more often, the officer present would be a senior officer. Sheen enquired whether one of Pixie’s superiors attended as a representative of 45the Gardaí, and she told him she didn’t believe so.

Sheen sighed. The picture that was emerging confirmed his gut feeling; the child’s body had been given the bare minimum of institutional attention and was not even yet being actively investigated.

‘Do you have a copy of the report here?’ Sheen asked Michael.

‘No, sir,’ said Mulligan. Sheen had expected as much.

‘What about a copy of the pink form?’ he asked. Michael Mulligan looked confused. The pink post-mortem form was the original record made during the autopsy examination, sometimes in duplicate, and used to inform the final write-up. Sheen explained, and Michael Mulligan disappeared into a side room and emerged less than a minute later holding what Sheen had requested. This form was blue; clearly a duplicate of an original, but it was legible and would give Sheen a window into the post-mortem. Sheen asked to see the remains.

Michael led them into the cold storage facility, opened a wall tray and deftly slid the sheet-draped contents onto a waiting gurney. The cargo was small, less than half the length of an average-sized body. Michael wheeled it back into the well-lit autopsy suite and removed the cover. Sheen stepped forward; his eyes fixed on what had been revealed to the cutting glare of the overhead lights.

The headless torso was tanned a deep peat brown, fixed in a foetal position, and rested on its side. The arms were clasped close to the chest, and the legs hitched right up, knees over elbows. It had clearly shrunk. This, added to the discolouration and perfect preservation from the acid waters of the peat bog, made the remains other-worldly, 46alien. Sheen completed a tour round the remains, opening his senses for an important first impression.

‘Remains’ seemed fitting. What lay before him seemed to hardly qualify as human, but of course, that was what this had once been. Sheen swallowed, forcing himself to get anchored.

This was a child’s body. And this was an unlawful death. Given the strong similarities between this body and that of Jimmy McKenna, Sheen judged it to date from around the same era.

The body was naked. And though his genitals were obscured from view, Sheen could tell it was male. He took another slow circuit round the boy’s body, this time with his phone in hand taking snaps as he went. He spoke, detailing what he observed as much for himself as for Pixie and Michael, who had given him space.

‘Head has been removed,’ commented Sheen, now hunkering down, examining the ragged stump of the boy’s neck. On closer inspection, Sheen observed the yellowed bone of the neck and spinal column. It looked like the killer had taken more than one cut to dismember the boy.

‘Appears that decapitation,’ he paused, searching for the best term, ‘was the result of hacking,’ he finished. Not exactly what he wanted, but he wasn’t a medical professional.

Then Michael spoke up. ‘I’ve seen similar wounds, though never on a body like this.’

Sheen glanced through the form; saw no mention of a possible weapon.

‘Axe?’ he opined.47

‘I’d say a shovel,’ Michael replied. Which made sense. The boy’s body had been found in a buried cask. Someone had been digging.

‘So, perhaps, the head of this boy may be buried close to where the original body was discovered in the bog?’ pondered Sheen. No response to this from Michael this time, or Pixie.

He doubted that the dig had missed something as obvious as the head of a little boy. Instinct told him that it was gone and would never be recovered, certainly not from the Monaghan bog that had yielded his torso. Perhaps the decapitation, like that of the donkey, was part of the masquerade to suggest a sick ritual, or maybe this was genuine, or perhaps just a means to conceal the identity of the child victim?

Sheen cleared his throat; the better to shake away this analysis, that could come later, and right now it was beginning to interfere with his absorption of the evidence. He brought his face close to the boy’s auburn, leathery torso where the arms were still pressed against his thin chest. A faint whiff exuded from it: iodine and suede.

‘Both hands have been removed, just above the wrist,’ he said. The yellowed tusk of the boy’s lower arm bones protruded where the flesh and skin had either receded over time or through tanning and dehydration.

‘Cleaner cut,’ interjected Michael. ‘But probably with the same instrument.’

Sheen nodded a quick reply. The same instrument meant the flat blade of a shovel. Easier to nick and slice off a little boy’s hands than his head. Sheen changed position to examine the boy’s back. It had been carved, 48like a side of wood, the deep cuts now indented over time. Sheen felt sparks ignite in his ribcage: recognition and excitement, but anger too at what he was seeing.

Michael joined him. ‘Is that an inverted cross?’

‘Yes and no,’ replied Sheen, coming closer to the body, again taking photographs. The ‘T’ of what indeed appeared to be a cross had been sliced deeply into the skin of the boy, ending, as though inverted, a little shy of the base of his spine. The shaft scored the length of his back. Sheen traced his gloved finger along the line of the cut.

‘This part is, but it’s not what I think we’re looking at,’ Sheen explained. He moved a fingertip along the curved arc of another cut. This one emerged from the shaft of the inverted cross just south of the ‘T’ and swept in a wide arc across the breadth of the child’s back, ending in a tight kink like a cat’s tail, or the blade of a sickle at the boy’s shoulders. Sheen recognised it instantly. The same symbol had been traced in salt at the centre of an inverted pentagram in the old newspaper report he’d found at Clones Library earlier. The excitement of the find was in his voice when he spoke.

‘Taken together this is the symbol of Saturn. The crescent below the cross, it means the victory of the earth over the soul, or something like that,’ said Sheen. Michael made a faint sound, something between agreement and accolade.

Sheen moved to the boy’s shrunken feet. His blackened heels were like basalt eggs. Sheen recorded more images. With the hands and head missing, identification would be very difficult. DNA testing could be done on a skin sample but would be helpful only if there was a record of 49the child’s genetic code on file. Given that this crime likely dated from the 1970s, he had more chance of finding the kid’s head if he went digging with his lucky shovel in Monaghan. Sheen’s eyes lingered on the red horn of his large toenail. He clicked his fingers, reached into his pocket with his free hand.

‘I’m gonna need to take a small nail sample,’ Sheen said.

Michael’s expression was blank, but not yet dismissive. He looked where Pixie stood waiting against the desk. She was Gardaí; their body, her call. She turned a questioning stare back at Sheen.

‘I want to have it sent off for testing, a bone spectrum analysis,’ he explained.