Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

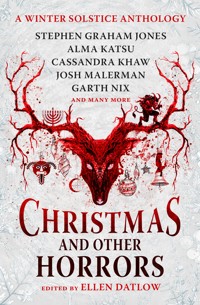

Hugo Award winning editor, and horror legend, Ellen Datlow presents this chilling horror anthology of original short stories exploring the endless terrors of winter solstice traditions across the globe, featuring chillers by Tananarive Due, Stephen Graham Jones, Alma Katsu and many more. The winter solstice is celebrated as a time of joy around the world—yet the long nights also conjure a darker tradition of ghouls, hauntings, and visitations. This anthology of all-new stories invites you to huddle around the fire and revel in the unholy, the dangerous, the horrific aspects of a time when families and friends come together—for better and for worse. From the eerie Austrian Schnabelperchten to the skeletal Welsh Mari Lwyd, by way of ravenous golems, uncanny neighbors, and unwelcome visitors, Christmas and Other Horrors captures the heart and horror of the festive season. Because the weather outside is frightful, but the fire inside is hungry... Featuring stories from: Nadia Bulkin Terry Dowling Tananarive Due Jeffrey Ford Christopher Golden Stephen Graham Jones Glen Hirshberg Richard Kadrey Alma Katsu Cassandra Khaw JohnLangan Josh Malerman Nick Mamatas Garth Nix Benjamin Percy M. Rickert Kaaron Warren

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 562

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Introduction

The Importance of a Tidy Home | Christopher Golden

The Ones He Takes | Benjamin Percy

His Castle | Alma Katsu

The Mawkin Field | Terry Dowling

The Blessing of the Waters | Nick Mamatas

Dry and Ready | Glen Hirshberg

Last Drinks at Bondi Beach | Garth Nix

Return to Bear Creek Lodge | Tananarive Due

The Ghost of Christmases Past | Richard Kadrey

Our Recent Unpleasantness | Stephen Graham Jones

All the Pretty People | Nadia Bulkin

Löyly Sow-na | Josh Malerman

Cold | Cassandra Khaw

Gravé of Small Birds | Kaaron Warren

The Visitation | Jeffrey Ford

The Lord of Misrule | M. Rickert

No Light, No Light | Gemma Files

After Words | John Langan

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

About the Editor

Also edited by Ellen Datlow and available from Titan Books

When Things Get Dark: Stories Inspired by Shirley Jackson

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Christmas and Other Horrors

Print edition ISBN: 9781803363264

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803363271

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: October 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Introduction © Ellen Datlow 2023

The Importance of a Tidy Home © Christopher Golden 2023

The Ones He Takes © Benjamin Percy 2023

His Castle © Alma Katsu 2023

The Mawkin Field © Terry Dowling 2023

The Blessing of the Waters © Nick Mamatas 2023

Dry and Ready © Glen Hirshberg 2023

Last Drinks at Bondi Beach © Garth Nix 2023

Return to Bear Creek Lodge © Tananarive Due

The Ghost of Christmases Past © Richard Kadrey 2023

Our Recent Unpleasantness © Stephen Graham Jones 2023

All the Pretty People © Nadia Bulkin 2023

Löyly Sow-na © Josh Malerman 2023

Cold © Cassandra Khaw 2023

Gravé of Small Birds © Kaaron Warren 2023

The Visitation © Jeffrey Ford 2023

The Lord of Misrule © M. Rickert 2023

No Light, No Light © Gemma Files 2023

After Words © John Langan 2023

The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of their work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

INTRODUCTION

WHAT do you think of when you think of the celebrations focused around the winter solstice? Gift-giving, eating and drinking with friends and family around a fire?

But what if someone in your family wanted to kill you? What if the jolly, gift-giving Santa Claus got pretty damned angry if he didn’t get what he considered his due? What if you discovered that your friends lied to you? What if the rituals you’ve honored over the decades are broached—just one time?

Even though many celebrate the winter solstice as a time of joy, there is a darker tradition of ghost tales and horror stories taking place around the time of the winter solstice. The stories in this anthology embrace that dark tradition by presenting the unholy, the dangerous, the horrific aspects of a time when families and friends come together—for better and worse.

Here you’ll find the Celtic Mari Lwyd; wood demons of Finnish mythology; the Schnabelperchten—creatures from Austrian mythology that will punish you if your house isn’t up to their standards of cleanliness during their annual visit; the Lord of Misrule, whose origin dates back to Roman times and who was appointed a master of revels; a Santa Claus who is not the nice guy we like to believe he is; a carnivorous witch; young gods overthrowing older gods; a time tripping nightmare on the shortest day of the year, and other strange horrors.

I hope these stories will amuse you while causing that cold finger of dread to creep up your neck.

THE IMPORTANCE OF A TIDY HOME

Christopher Golden

IF anyone had told Freddy he would one day be elbow deep in a garbage bin behind a third-rate restaurant in Salzburg, searching for a late dinner, he would have scoffed at them. Haughtily, of course, the way professors are meant to scoff. That had been his occupation—both vocation and avocation—until 1957, when addiction to morphine had led first to petty crimes and then to a psychiatric hospital. This was before Austria had begun to approach drug addiction as a problem requiring treatment instead of punishment, and so there had been a bit of time in prison as well.

Prison had helped.

Freddy knew that wasn’t the case for many who had been in his position, but for him, prison had been a time of clarity. Without drugs, without alcohol, without distraction. He had learned that the mania he had always experienced, the way his skull felt like a hive of agitated bees, could be survived. And if that meant he sometimes saw things that weren’t there, or said things that others interpreted as either a bit mad or wildly inappropriate, well, that was the eccentricity of a professor.

Of course, once he had been released, no one wanted him as a professor anymore. Or anything else, for that matter.

By that night, the fifth of January, 1973, he had been living without a home for nine years, during which time he had never diluted his brain with a single ounce of alcohol, nor the use of any illegal substance. But since the polite society of his city had finished with him, Freddy had finished with it. He lived in its parks and haunted its alleys, he accepted the offerings of strangers but never met their eyes, he forged a life from their castoffs, from food and clothing discarded and forgotten just as he had been.

The first time he saw the Schnabelperchten walking the streets in their black robes, with their gleaming shears and their enormous, bone-like beaks protruding from beneath their hoods, it did not surprise him that they passed him by. Their duties could not bring them to his doorstep, because of course he had none. No threshold, no door, no visitors, nowhere to mark the start of a new year, only the continued existence of life invisible, a creature unseen. Quiet, even when loud.

The Schnabelperchten were even quieter.

Tonight, he and his friend Bern were out together in search of food. Freddy had forgotten the date until he spotted the creatures. It was the fourth January fifth he had seen them, and each time they had ignored him. He presumed they appeared every year and that he had slept through their arrival in the years he had missed them.

He watched as they crept along the streets, leaving no trace of their passage through the lightly falling snow. They were delicate creatures, some with their brooms and others with shears, and no door was ever locked to them. Every home opened, no matter how tightly it had been shut up for the evening.

“Chi chi chi,” they whispered in the hush of falling snow, and they went about their business.

Freddy climbed down from the side of the garbage bin, holding the bag of leftovers he had known he would find there. The kitchen staff always wrapped the food being discarded and placed it in a single bag along with the uneaten bread. The restaurant manager frowned upon this practice and had shouted at his employees for encouraging nightly visits from the homeless, but they were kind and waited until he was out of the kitchen before putting out the bag. This place was no Gablerbräu, but the staff there had never been so kind, and even if they had been, Freddy did not like roving around that part of the city late at night. It felt more empty, more open, as if anything could happen. Here, there were more homes, lived in by people who desired quiet evenings, away from the downtown.

A clang of metal echoed along the alley.

Bern had let the garbage bin’s cover come crashing down. Freddy glanced anxiously around, afraid they would draw unwanted attention. If they created any nuisance, their lives would become more difficult. Sometimes he grew frustrated with Bern for his clumsiness, though never for his addiction. Alcoholism made Bern a fool, but it was the engine that drove him, as much a part of him as his left leg.

“Hush,” Freddy said in German, more a plea than an admonition. “Don’t be a fool.”

Bern did not so much as look at him. Thin and gray, unshaven and unkempt, in an ill-fitting suit that did nothing to disguise the state of his dissolution, he staggered from beside the bin to stand next to Freddy.

“Don’t you see them?” he whispered.

Freddy glanced from the alley into the street again. The Schnabelperchten were still passing by, spread out like a hunting party, perhaps twenty feet separating each from the next, some on one side of the street and some on the other. The most fascinating thing about them was the size of those beaks, at least eighteen inches in length, but wide enough that if one could draw back their hoods, the creatures would not have any face at all—or so it seemed. Only beak, the gray-white of bone. The first time he had seen them, nine years ago, Freddy had been reminded of old photos of plague doctors, but these were not masks, nor did they have anything like goggles to resemble eyes.

They glided along the road. Even as he looked, he saw one approach a door that led to a stairwell, rising to the apartment above the flower shop across the street. Silently, Freddy hoped the owners of that shop kept a tidy home.

“Freddy,” Bern rasped, shaking him by the shoulder. “Don’t you see them?”

“Hush. Of course I see them.”

“Are they ghosts?” Bern whispered. “They don’t look like ghosts—they seem solid enough. Are they demons?”

Freddy pondered that. “Honestly, I’m not really sure what they are, though they are certainly not people. They are Schnabelperchten.”

The word caused Bern to screw up his face in a way that made him look like a toddler given an unfamiliar vegetable for the first time.

“I don’t understand. You’ve just said they’re not people, not human. Aren’t you frightened?”

Acid burned in Freddy’s gut. His laugh was bitter. “Of the Schnabelperchten? Certainly not. You and I have nothing to fear.”

“But what are they?” Bern prodded.

Freddy gazed at him, trying not to let his friend see the flicker of distaste that passed through him. “I forget, sometimes, that you are not from Salzburg—”

“What has that got to do with anything?”

“If you were a child here, you would know the story,” Freddy replied. He patted Bern’s back. “Come with me.”

His friend hesitated, but when Freddy began to walk along the alley, Bern followed. Most of the Schnabelperchten had already passed by, but there were a few stragglers who had gone into the homes along the street and only now emerged. Without eyes, it was difficult to know for certain whether the Schnabelperchten noticed them, but they showed no interest. They might as well have been dust motes in the air or dry leaves that skittered along the road.

“Do they not see us?” Bern asked.

“They are like most of the people in this city. We are invisible to them,” he replied.

One of the Schnabelperchten passed by, and in the light of a streetlamp they could see blood on the blades of its shears, dripping onto the street. When Bern saw that blood, he looked as if he might be sick.

“Come,” Freddy said. “Those two.”

He pointed at a pair of the creatures further up the block. They approached the door of a two-story home. Bern followed anxiously as Freddy crept up behind the two beaked Inspectors.

One of them extended a skinny hand with long fingers like the legs of spiders and turned the doorknob. It ought to have been locked, and Freddy believed that if he or Bern had tried the knob it would not have turned. But for the Inspectors, no door was ever locked. They opened the door and stepped across the threshold. Freddy caught the door before the Schnabelperchten could close it. He heard Bern suck in a terrified breath behind him, but the Inspector who had tried to shut the door just left it and began to move through the house.

“I’ve followed them before,” Freddy whispered, worried more about disturbing the family living in the home than drawing the attention of the creatures.

Inside, the Inspectors began to move about the place, spidery fingers gliding along tabletops in search of dust, beaks lowering to discover if the floors had been swept or vacuumed.

“Chi chi chi,” they said quietly, without mouths.

One in the kitchen brought its head down close to the stove and seemed to study its surface for much too long, perhaps deliberating on its relative cleanliness.

Freddy leaned over to whisper into Bern’s ear. His friend was trembling.

“It is the Epiphany,” he said. “Christmas ends tonight. January first begins the calendar year, but tonight is truly the beginning of the New Year. The Schnabelperchten bring happiness and blessings for the coming year, but only to those who are properly prepared for this new beginning, who have set their houses in order.”

“What happens if they enter a home that has not been tidied in anticipation of the new year?” Bern whispered.

Bern watched intently as one of the Inspectors went up the stairs, shears hung at its side. Freddy understood his fear, even found it somewhat delicious, but Bern was his friend and he knew there was cruelty in allowing him to continue in ignorance.

“Something horrible,” Freddy said. He took his friend by the wrist and shook it, forcing Bern to look at him. “But we have no home. They are not here for us. Do you see?”

At last, Bern seemed to exhale.

Moments later, the Inspector who had gone to the second floor returned, its shears still clean. It joined its fellow Schnabelperchten and the creatures walked right past Freddy and Bern and out the door. This time it was Bern who led the pursuit of them.

Out on the street again, the breeze was chilly enough to remind them they were alive. Snow fell gently, a hush that felt like it made some sound just beyond the limit of their hearing, though it was only silence.

In morbid fascination, they followed the two creatures while other Schnabelperchten drifted along the street around them, wordless and intent. Moving amongst them, ignored as if invisible, long after midnight and in the quiet hush of gently falling snow, they might as well have been wandering the street inside some Christmas snow globe.

“What are they?” Bern wondered aloud.

“Spirits,” Freddy replied. It was the only word that felt acceptable. He had so many questions but no real answers. The Schnabelperchten came out one night a year, which meant every other night they were somewhere else. If he could ask them anything, it would be about that.

Schnabelperchten glided silently from building to building. Up along the road, Freddy saw others crawling on the outside of several taller buildings, cloaks billowing in the breeze as they slid open windows that should have been locked. One perched at the edge of a rooftop, scuttled to a domed skylight, opened it and vanished within, its beak leading the way.

Somewhere, Freddy heard a baby crying. The infant’s wail pierced the oh-so-silent night, and then abruptly ceased. He pressed his eyes tightly shut, forcing himself not to imagine the things his darker fears wanted him to imagine.

They reached the house where the two Schnabelperchten they were following had gone inside. Bern turned the knob and the door opened. It had unlocked for the Inspectors and remained unlocked, at least until the creatures departed. Bern did not hesitate now—he stepped over the threshold as if he had forgotten Freddy entirely, too curious. Too eager.

Suddenly this felt too intimate. They were intruding on this quiet moment, this breath taken and held until sunrise, when the new year would really begin in earnest. He had a spot behind an old, crumbling school building where heat vented from inside created a small bubble of warmth near the dumpster. The roof’s overhang kept the elements off his head except on the worst nights, and he wanted to go back there now, to his spot.

“Bern,” he rasped, trying to grab his friend by the back of his coat.

But Bern had passed through the home’s little entryway, where coats hung haphazardly on metal hooks—too many coats, too few hooks—and three pair of winter boots were arranged along the wall. Not impeccably neat, but he thought they would pass inspection.

Then he followed Bern into the living room, and he froze.

Antlers hung from the wall above the fireplace. The room held an eclectic array of furniture, most of it threadbare and in mismatched floral patterns. A small black-and-white television stood on a tray table beside a fat armchair. Magazines were strewn across the coffee table and piled beside the armchair. An open box of biscuits sat amongst the magazines. A coffee cup and a plate of crumbs and grape stems had been abandoned there. The entire room needed to be straightened, vacuumed, dusted, but the worst of it was the stink of cat urine and the litter box in the far corner, in front of an overstuffed bookshelf that looked as if the books had been stacked and piled by an angry drunk.

Across the room, through an arched entryway that led into the hall, Freddy saw the two Schnabelperchten return from the kitchen and start up the stairs. Bern padded across the stained carpet to follow.

Freddy lunged to grab his arm. “Don’t be a fool.”

Bern turned to glare at him. “They can’t see us.”

“We should not intrude,” Freddy said. When Bern ignored him, Freddy grabbed him again. “You don’t want to see this.”

Bern scowled, shook himself loose, and darted for the steps before Freddy could try to drag him from the house. Freddy cursed under his breath and followed. He reached for Bern’s coat a third time, but the other man was younger, quicker, and reached the second floor before Freddy could catch up to him.

The top step might as well have been a brick wall. This was as far as Freddy was willing to go. On that last step, he watched as Bern slunk along the corridor and peered into one room, then moved on to the next. Before he reached that room, the noises began.

From the room at the end of the hall came a sound Freddy had heard once before in life, and far too often in nightmares. The sound of shears plunging into flesh—a wet, violent puncture—and then the hushed metal clack of the shears being used.

Bern reached the door from which the noises emanated.

Freddy had warned him, had as much as told him without telling him, but the fool had needed to see for himself. Grim fascination, perhaps, or pure sadism—Freddy didn’t think it mattered which. In that bedroom doorway, Bern stood with his eyes widening and let out a scream of horror. Freddy knew he should run, but his feet moved him in the wrong direction, toward his friend instead of away.

He rushed up behind Bern and clamped a hand over his mouth. It muffled the scream, and a second later Bern went silent, perhaps realizing how foolish he’d been.

“Quickly,” Freddy whispered in his ear. “Let’s go.”

Bern whimpered but did not move. Freddy nearly dragged him, but in glancing up at his friend, he had a view over Bern’s shoulder and into the bedroom. One of the Schnabelperchten straddled the woman on the bed, using its shears to open her from groin to breastbone. The whole room was in disarray, clothes piled everywhere, plates and cups on the nightstands.

On the floor, the second Inspector knelt beside the corpse of the husband. His guts had been laid open by the shears of the Schnabelperchten and the creature had reached both hands into the dead man’s torso and now slid intestines out from his steaming insides, hand over hand, arranging them around the body with a kind of artistry.

The Schnabelperchten disemboweling the man on the floor kept working, but the one on the bed had frozen in the midst of cutting, disrupted by Bern’s scream. Shears in hand, it turned its eyeless, mouthless beak toward them and Freddy could feel the weight of its regard, knew that despite the lack of eyes, the creature studied them.

The dead woman’s head lolled to one side. Perhaps she had not quite been dead, but now her sightless eyes seemed to gaze at the two men in her bedroom doorway as if accusing them. As if asking why they had not stopped this, why they did not step in, even now, to prevent the further evisceration and desecration that would unfold here.

Freddy held his breath, telling himself that none of this was his fault. These people had comforts that had been beyond his grasp for years. They had heat and running water and a roof over their heads. They had quiet nights in which they could pretend the rest of the world did not exist. They had food to eat, and they’d had each other. He told himself they must not be from Salzburg, or they were jaded young people who did not believe in the old stories. He told himself perhaps they had been unpleasant people whose neighbors and friends did not care for them enough to warn them, to teach them the importance of a tidy home.

“Freddy,” Bern whispered, his voice cracking.

The hooded Schnabelperchten tilted its head, its focus more intent.

“Chi chi chi,” it whispered, with no mouth.

Freddy backed away from the bedroom doorway, tugging Bern with him. The moment they began to retreat, the Schnabelperchten on the bed returned to gutting the woman, no longer interested in the witnesses.

Hauling Bern behind him by the wrist, Freddy bustled down the stairs and out the front door. It clacked shut behind them, the noise like a whipcrack in the night. The snow fell thicker and heavier now and the creatures on the street moved like ghosts, their soft chi chi chi carried on the wind.

Instinct sent Freddy down a side street. A Schnabelperchten emerged alone from a doorway, gore dripping thick and red from its shears. Its beak did not turn toward them, but it paused and stood in statuesque silence as they passed.

“Where are we going?” Bern whispered, voice cracking.

“My spot,” Freddy said, as if it were the stupidest question in the world.

Bern twisted his wrist free and stopped, there in the quiet of Epiphany Night. “Too exposed. We need to hide.”

For the first time, Freddy saw the tears in his eyes, the wetness of his cheeks, red from the cold. He wanted to tell Bern they had nothing to worry about, that they had no homes and therefore were in no danger, but he had not liked the way the creature inside that second house had noticed them. Looked at them, if it could be said to look at anything.

“Where, then?”

Bern wiped at his tears. He hesitated a moment as if making a decision, then waved for Freddy to follow. With Bern leading the way, they jogged along the street, then through a side alley, alongside an old stone wall, then behind an ugly, no-frills hotel. Through a gap in the fence behind the hotel, they emerged in the lot of a used car dealership and auto body shop. The pavement had cracks everywhere, weeds growing up between them.

Freddy looked back through the gap in the fence and felt a ripple of relief. There was no sign of the Schnabelperchten.

“I think we’re okay,” he said.

“This way,” Bern replied.

He led Freddy to the other end of the car lot. There were junkers back here, probably only used for parts. Bern brought him to an ugly gray Auto Union station wagon from the late 1950s, tucked between the shells of cars in even worse condition. Rusted and dented, the windshield covered in snow, the wagon was otherwise intact. The tires sagged like an old man’s belly.

Bern opened the driver’s door, head low, and gestured for Freddy to get in on the passenger side. Aside from the wagon’s rear hatch, those were the only two doors. Freddy glanced around, but he realized this wasn’t the sort of place that would have a security guard. There were no brand new vehicles here.

Inside the car, he tried to close the door as quietly as possible, gritting his teeth at the rusty squeal of its hinges. Bern shut his door, and then they were out of the wind and the snow. From inside, Freddy could see the windshield was spider-webbed with cracks and covered in grime under the coating of falling snow. It was certainly cold in the car, but better than being outdoors tonight.

“The owner of the shop knows I sleep here,” Bern said, his voice dull and hollow, as if all the life had been drained out of him. “We can hide until morning. They… those things will be gone by morning, right?”

Freddy nodded. It surprised him that Bern had brought him to this shelter. They had known each other for long enough that Freddy thought of Bern as his friend, but if the owner of the car lot really didn’t mind Bern sleeping in this dead, rusty car, it was a secret he had taken a risk in sharing. If Freddy told others, soon there might be a dozen people trying to sleep in these cars, and surely that would lead to the owner having a change of heart.

“Thank you,” Freddy said.

Bern understood. “I’m trusting you.”

“I know.”

That was it.

Freddy thought Bern would want to talk about what they had seen, but Bern only shivered and then climbed over the seat into the back of the wagon. There were blankets back there, dirty and musty, but warm. Freddy watched as his friend began to dig himself into a kind of nest of blankets and clothing. There were empty bottles and crushed cardboard boxes, and a squat wooden crate that seemed to be Bern’s pantry, with a box of crackers, a jar of some sort of spread, and other things impossible to make out in the dark. In the front seat with Freddy were half a dozen dog-eared books and the debris of food cartons.

It wasn’t much, but it was so much better than Freddy’s spot. Safer, drier, warmer. He found his envy simmering and forced it away. If he played his cards right, and Bern really trusted him, maybe he could find a junker back here with intact windows and set up a similar berth without pissing off the car lot’s owner. Wordlessly, he promised himself he would do nothing to jeopardize Bern’s good luck.

“You have a spare blanket?” he asked.

Bern looked at him. With obvious reluctance, he peeled off one of his own blankets and pushed it over the seatback. Freddy knew words were not sufficient, so he tried to put the depth of his gratitude in his eyes and the nod of his head, and then he swaddled himself as best he could and lay down across the front seat.

He was sure adrenaline would keep him awake, that he would see the Schnabelperchten when he closed his eyes and be unable to sleep. But in the midst of such worries, he drifted off…

* * *

…And woke to someone screaming his name. A hand gripped his shoulder, shook him hard. Freddy twisted around in the seat and looked up to see wide eyes and a face etched with terror. Bern loomed over him from the back of the wagon, pointing, shouting.

Freddy finally got it, the words making sense.

“Start the car!” Bern screamed at him. “Start the fucking car!”

The words didn’t make sense at all. The veil of sleep had finally been stripped away and Freddy knew where they were, in that stretch of junked cars at the back of the parking lot. How was he supposed to start this car?

“Get the keys, Freddy! Under the floormat!”

Bern started to drag himself over the seat.

Freddy grabbed his wrists and sat up, pushing him back. “Christ, Bern. Calm down. You’ve had a nightmare, that’s all.”

Bern tore his right hand free and punched him in the face. Screamed, spittle flying. “Get the fucking keys!”

Angry, Freddy nearly hit him back, but he still had Bern’s blanket wrapped halfway round him and that reminded him that his friend had been hospitable enough to trust him with his secret spot, to get him warm and out of the snow.

Bern ripped his other hand free, but now he stared at Freddy from behind the front seat with pleading eyes. “Freddy, they’re here.”

He saw movement to his left. A dusting of snow clung to the passenger side window, but Freddy could see a figure just beyond the glass, and when he went still, trying to tell himself it was just some security guard, he heard a sound.

“Chi chi chi.”

The bone-white beak, gray against the snow, leaned forward to peer eyelessly into the car. The creature tapped its bloody shears against the window, as if asking him to unlock the door.

This time, Bern whispered. “The keys are under the mat, Freddy. Start the car.”

Freddy stared at the Schnabelperchten. It tilted its head, just as it had back in that house while it cut open the woman on the bed. He wondered if this might be the same one, but it didn’t matter.

Another rapped at the glass of the hatch at the back of the station wagon. Freddy whipped his head around and could see the shadows of others beyond the snowy windows. They should not have been here. He had followed them in previous years and they had always treated him as invisible. Why would they follow him and Bern tonight? Why pay any attention to them at all?

“Freddy, please,” Bern said, weeping in terror.

Then it struck him. The keys under the mat. He turned to stare at his terrified friend. “This is your car. You live in your car.”

Bern smashed his hands against the back of the seat and screamed at him to get the keys. This time, Freddy acted. Shoved his hand under the mat, dug around, found the keys, chose the correct one for the ignition the first time out, jammed it home, twisted it… and the engine growled, trying to turn over. He wondered how often Bern started the car to keep the engine from becoming a block of useless metal and guessed the answer was not-often-enough, but still he tried. He let it rest, counted to three, turned the key again. The engine choked and snarled and tried its best, and Freddy let it rest again.

“You live in it,” he said, mostly to himself. He glanced around at the debris of meals, of life—a dirty blanket, some dog-eared books, takeaway boxes stealthily donated by restaurant staff at the end of a night.

Bern lived in his car. It was his home. And it was an utter mess.

The rear hatch of the station wagon clicked and opened, letting in a gust of frigid air and a swirl of snow. It opened as if it had never been locked at all, just like the doors of each of the homes the Schnabelperchten had visited.

Freddy glanced in the rearview mirror as Bern screamed a different sort of scream. This one held as much sorrow as it did fear. One of the Schnabelperchten bent and thrust his arms and beak into the back of the wagon, grabbed Bern by the legs.

“Chi chi chi,” it said.

Bern screamed and reached out, shrieked Freddy’s name, cried for help, in the moment before the thing dragged him out into the snow. Perhaps Freddy could have caught his arms in time and given the Schnabelperchten a fight, but instead he turned the key in the ignition again.

Coughing. Growling. Not starting.

Freddy began to cry.

Out the window on his side of the car, another of the things leaned in close to peer at him through the snowy glass. On the passenger side, the first one he’d seen grew impatient and simply opened the door, the lock notwithstanding.

Freddy turned the key.

The engine roared to life.

The Schnabelperchten at the passenger door bent its head and reached across the seat toward him. “Chi chi chi.”

Freddy ratcheted the gearshift into drive and hit the gas. The car hitched once and then surged from its place amongst the junkers. The creature inside the car snagged his jacket, but then the open passenger door struck the rusted shell of an old Volkswagen. The door slammed on the Schnabelperchten. Its cloak caught on the rusted, twisted bumper of that Volkswagen and the Schnabelperchten clawed at the front seat of Bern’s car before it was dragged from the vehicle.

With the passenger door still hanging open, Freddy could hear Bern back amongst the junkers, screaming in the snow. He did not glance in the rearview mirror or try to look over his shoulder. The hatch at the back of the station wagon remained open and he might have seen what they were doing to his friend, might have seen those shears employed at their gory work.

Hands locked on the steering wheel, he drove through the snowy parking lot. The tires were so low they were nearly flat and he didn’t know what that might mean, how far he could get in this weather on those tires. So he drove.

He clicked on the windshield wipers to scrape snow off the cracked windshield. They worked, but poorly, and not well enough to keep him from smashing into the front end of a used Mercedes proudly on display near the front of the used car lot. The Mercedes banged aside and Freddy kept going, shaken, headed for the front gate.

The impact shattered the windshield. Splinters showered around him as he raised one arm to shield his eyes. When he lowered that arm, face dotted with little specks of blood and glass, he was stunned to find the car still moving. His foot had come off the gas and now he floored it again, twisting the steering wheel, heading for the river. He needed to get away from Salzburg, away from the Schnabelperchten, but as he drove he saw them in the falling snow. They emerged from rowhouses and apartment buildings, some of them watching him go in silence, their heads swiveling to follow as he passed.

The car had been Bern’s home. Did they consider it his, now? Bern was dead and the car was in his possession. What were the rules? Did they need to kill him because of what he had seen, or simply out of spite? Would they let him go?

The engine coughed. He wondered how far the car would get him, how much gas might be in the tank. If he could put the river between himself and this group, he thought he could escape the city before they caught him. How far would he have to go before he was beyond their reach?

One of the headlights had shattered when he hit the Mercedes. The other was weak. Snow and wind buffeted him through the broken windshield. But he saw three Schnabelperchten in the street as he approached one of the bridges across the river Salzach. Which bridge was this? The Lehener, maybe? In the snow it was hard to tell. And were there figures drifting across the bridge in the snow, dark robed creatures with bone-white beaks?

Freddy thought there were.

The engine coughed again.

The car isn’t mine, he wanted to scream through the broken windshield. I don’t own it. Never sheltered in it. His only home was the city itself. Not only the city, but all of Austria. His home was the sky and the ground below. His home was the whole of the world. The world might be anything but tidy, it might be insane and brutal and unforgiving, with all the mess and ruin the human race produced, but he could not be to blame for that. He refused. The people responsible for the mess of the world had never done anything but take from him.

Freddy turned toward the river. The old car jumped the curb. The impact would have blown those half-flattened tires, but the snow provided a cushion.

He popped open the driver’s door. Its rusty hinges shrieked. He took his foot off the gas and let the car roll down the embankment.

Freddy hurled himself from the car, hit the snow and tumbled twenty feet. Heart thrumming, he struggled to rise to his feet, but once up he managed to remain standing. The old, rusted, dented Auto Union wagon plunged into the river, bobbed for a few seconds, and then the river poured through the broken windshield and the car began to drown. Bern’s belongings, his blankets and clothes and the castoff debris of his life and home, floated up around the car and were quickly swept away by the river.

“Chi chi chi.”

Freddy whipped around and saw them through the snow. Three of them, coming along the embankment toward him from where they had been standing in the road, near the foot of the bridge.

He faced them, cold and tired and bruised, not sure where he could run.

“Chi chi chi.”

Too tired, in fact, to run. Angry, he walked toward them. Off to his left, the car vanished beneath the icy current of the river.

“It’s not my mess,” he said, staring at the one in the middle.

They kept walking, passing around him as if he weren’t there at all.

He turned to watch them go. Back on the street, they split up, angling toward homes along the road, where they would leave coins for those whose homes were tidy in preparation for the new year, and where they would make a deadly ruin of those who could not be bothered to care about the state of their homes and lives.

From a distance, he heard the sound again, carried on the wind.

“Chi chi chi.”

Freddy raised a trembling hand to cover his mouth, to muffle the sound of his sobbing.

Then he began the long, cold trudge back to his spot. He had to get the hell out of this city, as far away as possible. But not tonight.

Tonight he was tired and sad and broken, like the world.

Tomorrow he would start over, and one day he would be glad and warm and joyful again. He wished he could have said the same for Bern, and for the world. It was too late for Bern. For the world, he could not be sure. After all, he was just one man without a home or a family. What did he know?

END

* * *

Salzburg, Austria is one of my favorite places on Earth. My wife, Connie, and I went there on our honeymoon many years ago and I managed to return shortly before the pandemic hit. It’s as beautiful as ever, an intriguing, very self-contained city that nearly vibrates with the echoes of its history. It’s also a place with all kinds of folklore, and it’s the spot where I bought the Krampus ornament that hangs on our family Christmas tree every year. When I was poking around for something suitably unsettling for this story, it did not surprise me at all to find a bit of lore specific to the area around Salzburg. I loved the dichotomy of gentle household spirit or grotesque murder-monster, and that you get one or the other depending on how neat you keep your home. It’s a much more visceral version of telling children to behave or the bogeyman will get them. It creeped me out to think about it, and I hope I’ve passed that feeling on.

THE ONES HE TAKES

Benjamin Percy

IT was nearly noon on December 25th, and Joel Leer still hadn’t risen from bed. His wife Greta was awake beside him—he could tell from her breathing—but he did not roll over to nuzzle her cheek and wish her a Merry Christmas. He didn’t say a word to her or even look her way when he peeled off the blanket and swung his legs to the floor. He was only forty-two but moved with the pained slowness of the arthritic when he pulled on his robe and stepped into his slippers and trudged down the stairs.

There was no tree choked with colored lights. There were no stockings hanging from the hearth or carols sounding from the stereo or gingerbread cookies baking in the oven. Not in this house.

In the kitchen he opened and closed a drawer, then a cupboard, finding nothing he wanted. It used to be their tradition on Christmas morning to eat stollen smeared with butter and drink coffee spiced with rum, but his appetite was gray.

The dog whined from her kennel in the mud room. She was a yellow, long-haired dachshund named Daisy. They had purchased her from a breeder six months ago. She was supposed to make them happy, and she did. But today happiness wouldn’t be possible.

He opened the kennel’s gate and she burst out of it. He leaned over and gave her some scratches and she licked his hands and wormed in and out of his legs, panting happily. “I’m sorry it’s so late,” he said, and she cocked her head, studying him intensely. “You probably want to go outside?”

With that word—“outside”—she jerked into motion, scrambling her short legs across the floor, claws clicking on the hard wood. At the front door she let out a high-pitched bark and turned in circles, waiting for him.

He pulled on a hat and tucked himself into a coat, but otherwise remained in his slippers. He didn’t plan on stepping off the front porch. A cold blast of air greeted him. Vapor puffed from his mouth and he squinted in the light of the day.

Daisy raced to the porch steps and paused at the snow gathered there. Maybe five inches had fallen last night, with more to come later today. It always snowed on Christmas; that was practically a rule here in Minnesota. No one was out shoveling or scraping or salting their driveways. The plough hadn’t even come through yet. The world was shrouded white, and he was alone. Or so he thought.

“Go on,” he said, motioning toward the yard.

Daisy moved with hesitation, testing the snow with her paw and looking back at him.

“Go! Go potty!” He tried to muster some enthusiasm in his voice, but he felt like an actor forcing his lines. “That’s a good girl!”

The dog started down the steps and moved across the yard. Her legs vanished. Snow clung to her fur, forming a white skirt. She squatted to relieve herself.

Some clouds were piled up on the horizon, but the sky was otherwise a pale blue. Contrails were etched cleanly across it like the scrape of skates on a frozen pond. That’s where he was looking—up—when Daisy began to bark.

He couldn’t see her anymore—she had raced around the side of the house—but he could follow the messy trench she left behind. He called for her, “Daisy! Daisy, stop it! Daisy, come!” He tried clapping and whistling. But she would not come.

He thought about going back inside to fetch his boots, but there was something about the urgency of her barking that compelled him forward. The first few steps were a bracing chill. After that an ugly ache set in around his ankles that felt almost hot. He slipped and nearly fell at the corner, where the yard steepened slightly, and there he found Daisy.

Her long body was rigid, and her ears and tail were flattened. There was a metallic quality to her barking that made it feel like knives were being sharpened in his ears. A mound of snow, maybe blown by the wind or fallen from the roof, rested next to the house. This was the source of Daisy’s fixation. Maybe a possum had burrowed into it. He kept saying, “Stop! Stop, Daisy!” but she wouldn’t so much as look at him.

He wrenched her back by the collar, but even then she tried to keep barking, choking and hacking against the pressure.

He could see now what bothered her. From this angle the mound appeared like a sugary egg that was dissolving, and within it lay a body. A child’s body. Curled on its side. Dusted with snow in some places, buried entirely in others.

Joel no longer noticed the slush soaking into his slippers. He kneeled and brushed away the snow on the child’s face, revealing skin blued by the cold and eyelashes feathered with frost. A boy.

It couldn’t be him. It couldn’t be. But Joel said his name anyway, “Isaac?”

The boy’s eyes snapped open.

* * *

They had last seen him on Christmas Eve, one year ago. Isaac had changed into flannel pajamas and the three of them had read The Night Before Christmas. They had laid out cookies and milk by the fireplace, and Isaac had asked if he could have one.

“Sure.”

The plate was stacked high with krumkake, sugared rosettes, frosted cookies, and pinwheel dates. He selected a krumkake and the golden flakes crumbled down his chin when he bit into it with a crunch. “He’s not going to be mad, is he?”

“I’m certain he’ll get plenty of cookies tonight.”

“I don’t want to make him mad. I don’t want to be on the naughty list.” Isaac finished the cookie and took a sip of the milk as well and dragged his sleeve across his mouth to clean it.

“Time to brush teeth and get to bed, buddy.”

Isaac asked if he could stay up for one more minute. Just one more. And they said yes.

He kneeled before the tree to rearrange some of the wrapped and ribboned packages, and stare at the ornaments in wonder. The colored lights made a candied reflection on his eyes.

One minute became five became ten. Joel wished they had stayed there a thousand more. “Ready?” he said and held out his hand.

Isaac didn’t take it. Instead he turned his head toward the hearth. It was cold and dark and bottomed with ashes. “Don’t light a fire,” he said. “If you light a fire, he won’t be able to come. Okay, Dad?”

“Okay, sure.”

“Is it open?”

“Is what open?”

“The thing you open? Inside the fireplace? To make sure the smoke gets out? If the smoke can get out, he can get in.”

“The flue? Let’s check.” Joel knelt beside the fireplace, opened the glass doors, and swept aside the chainmail curtains. He craned his neck. “Good thing you asked.”

“Can I do it?” Isaac asked and grabbed the metal bar and creaked it forward and back. A cold draft breathed down and made a sound like whispering.

Isaac stepped back from the fireplace with a fearful expression.

“Everything okay, buddy?”

“Yeah,” the boy said, but he looked back at the hearth before mounting the stairs. “It was just darker and colder up there than I imagined.”

He and Greta tucked Isaac into bed, kissed his forehead, and whispered, “Dream about sugar plums and fairies, and we’ll see you in the morning.”

But in the morning he was gone, the sheets thrown back, the dent of his head still shaping the pillow.

They called for him when they checked in closets and under beds. They looked in the attic. They looked in the basement. They looked outside, walking the yard, where fresh snow had fallen that revealed no tracks. They returned inside, and again, and then again, they searched the house, shouting his name until their throats felt raw.

All the windows and the doors had been locked; they were certain of it. The only way in was the fireplace. When Joel felt the chill blowing down it—a whispery vacancy—he clanked shut the flue.

* * *

Joel hadn’t lit a fire since. Not until today.

In the living room, on the couch, Greta clutched the boy in her lap and tucked the blanket around him. “He’s so cold,” she said. “Hurry.”

“I’m hurrying,” Joel said. The firewood bin was in the garage. He brought an armful of logs and kindling into the house. He found some matches in the kitchen drawer and snatched yesterday’s newspaper out of the recycling. He twisted the sports pages into five wrinkly candlewicks. He flared a match and the paper caught flame. Onto it he fed sticks and then the split hardwood. Soon the room was full of dancing light and a popcorn crackle.

Joel joined Greta. He touched her but not the boy. Her cheeks were wet from crying. “It’s him,” she said. “It’s our little boy. He came back to us.”

Joel wanted—desperately—to believe. He was almost there. He gave her a stiff smile and did not mention the boy’s eyes. Isaac’s had been green. The boy staring back at them had eyes that gave off the strange blue light of glaciers.

His hair wasn’t shaved so much as hacked away. The rough job of a barber working with shears or a knife.

They debated whether to take him to the hospital or call the police. But they had only just found him, and it felt wrong to let go so soon. He existed as long as he was in their arms. And the police had not been kind, questioning them repeatedly, pitting them against each other. “When a child goes missing, a family member is usually to blame,” they had said.

The fire roared when the pressure shifted, and wind pulled at the chimney top. The orange light of the fire brought black shadows to the room. Color gradually returned to the boy’s skin. The blanket and couch cushions soaked through. A dripping puddle formed on the floor.

After an hour he still would not speak, but he sat up on his own when Joel brought him a mug of hot cocoa. “I even put marshmallows in it.”

The boy took the steaming mug with two hands and drank with tiny loud sips.

With the blanket off him, they had to acknowledge his clothes. He wore what appeared to be a leather onesie with shoulder straps. It was roughly stitched with what looked like yellowed ligaments. The gray mottled quality reminded Joel of a seal’s hide. A rank, oily smell came off it. His arms and shoulders were bare, and the pale skin of his back was scarred purple and scabbed red as if he had been lashed. One of the wounds wept blood.

Greta reached for the tissue box on the end table. She dabbed at the blood. “What happened to you?” she said. She was referring to the cut, yes, but she was talking about something much bigger as well. What had been done to him? Where had he been? How did he get home?

The boy pointed up.

“The roof?” Joel said, and Greta said, “You were on the roof?”

“You fell?”

“What do you mean, Isaac? What are you pointing at?”

The boy raised his hand even higher, as if to indicate he came from someplace even higher than they could imagine. He made a noise. It might have been a whimper or it might have been a word, “Sleigh.”

Joel heard a low growl behind him. He had forgotten about Daisy. The dog was peering around the corner, showing her teeth.

* * *

In Minnesota, in the winter, the days were white, but the nights were blue. Joel had lost track of time. A gloom settled over the neighborhood as the sun set.

He went to the window. The clouds were thickening again. A few flakes fell. His wife snapped on a lamp and suddenly all three of their reflections hung on the glass, transparent as ghosts.

The boy was staring out the window as well. His eyes were wide. His breathing came in quick pants.

“What’s wrong?” Greta asked him. “You can tell us anything, you know. We love you so, so very much.”

Joel said, “You’re safe here, buddy. I’ll protect you.”

The boy scrunched shut his eyes and shook his head. “No,” he finally said with a voice like a rusty hinge. “You didn’t before. You can’t now.”

“Isaac. Please talk to us,” Greta said and knelt in front of him and put her hands on his shoulders. “Please tell us what’s wrong. Please tell us how we can help?”

The boy stepped away from the window. The clouds appeared black now and the snow was falling more thickly, lashing at the glass.

His voice came as a shriek. “He’s coming back for me.”

“Who?” Greta said.

“Who’s coming?”

There was a short stack of wood in the living room. The boy grabbed several more logs and dumped them roughly into the fireplace. Sparks sprayed onto the floor.

“Isaac, what are you doing?”

“I got away. I hid in a bag, and then, when he wasn’t looking, I got away. He’s going to be so mad that I got away.”

“Who?” Joel said. “Who, goddamnit?”

“Him.”

“Him who?”

“He needs us. He uses us.” He holds out hands thick and glossy with calluses. “We build for him. Somebody has to do all that building.”

Joel remembered what the police had said—about how a family member is usually to blame for a child’s disappearance—and maybe they were right. He remembered the cookie he allowed Isaac to steal off the plate. He remembered the black gaze and the cold hiss of the chimney flue.

A sudden snow blinded the windows, as if a cloud had descended onto the house. The flakes swirled and eddied and fleeting shapes could be seen in them. There was a thump that shook the whole house. Several pictures fell from their hooks and glasses fell from cupboards and shattered on the floor. The dog began to bark, racing from a window to the door and finally to the fireplace. Then, above them, a creaking sounded as a great weight negotiated its way across the roof. With a whimper, the dog retreated to her kennel.

The three of them held each other and stared at the crackling hearth and waited for what was next. Christmas had finally returned to their home.

END

* * *

In the Andy Williams song, “The Most Wonderful Time of the Year,” he sings not just about the joys of Christmas, but about the ghost stories, and that’s how I always think of the holiday. It’s Tiny Tim saying, “God bless us each and every one,” but it’s also the Ghost of Christmas Future pointing a bony finger toward a gravestone that reads Ebenezer. It’s sugar plum fairies, but it’s also the rat king creeping through a darkened living room. It’s George Bailey shouting, “Merry Christmas, Bedford Falls,” but it’s also George Bailey perched on a bridge over a winter river. I can’t believe in the good without the bad, light without shadow. And there’s nobody who deals in joy and horror more than the big man—Santa—who’s always watching, always judging, and punishes or rewards us like a terrible god. When I think of the dark throat of the chimney and something stirring inside it, I get the chills. Who’s making all those toys? How do these so-called elves (the little people who… might just be children) come to find themselves indentured? That’s the unsettling spirit of “The Ones He Takes.”

HIS CASTLE

Alma Katsu

IT starts with banging at the door.

We expected as much. We’d been warned on our first night in this small Welsh village down at the Bloody Highwayman, the village pub. It’s decorated for Christmas, garlands strung over the bar and festive red bows on each of the taps. The barkeep wore a red Santa Claus hat at a rakish angle. “There’ll be revelers coming to your door one night,” the barkeep had said as he drew a lager for my husband Trevor. “Nothing to fret about.”

“Like carolers?” Trevor had asked.

The man behind the bar had laughed. “Not exactly. It’s more of a local tradition. Mari Lwyd: the grey mare. You’ll see… If they show up at your door, just give ’em a pint or a nip and they’ll be on their way.”

We hear as they approach, all drunken laughter and careless footfall echoing down the cobbled lane. We’re outside of Llanbradach, not far from Caerphilly, which is just north of Cardiff. If asked, we tell people we’re here for the holidays, Christmas and Boxing Day and the New Year, that we needed to get out of London for a while and that we find Wales restorative. Uniquely restorative, you might say. We’re both from here originally, though it was a long time ago.

We’ve no relatives left to visit.

Something besides familial obligation draws us back to the ancestral sod. Something not so easily explained.

We’ve rented a proper old cottage for our stay, just down the road from the local baronial estate, Phillips Hall. We could’ve stayed there, rented a room in the drafty wing they let out to guests, but found this place on Airbnb, a barely renovated farmer’s shack. It’s got low beams and tiny rooms, and the only heat source is the cast iron wood burner tucked in an inglenook. There’s one bathroom and a single bedroom only slightly larger than the bed that sits in the center. According to the listing, it dates to the 1700s but to me it feels like home.

I’m interrupted in the middle of my thoughts by the knocking. Bang, bang, bang.

The revelers the barman warned us about. Why have they picked this house, I wonder. It’s not festive looking, not compared to some of its neighbors, which glitter with strings of fairy lights and ornaments that wink from behind a window. The people who live there are likely to be celebrants and would welcome wassailers. Our rented cottage is cheerless. A blank slate.