11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

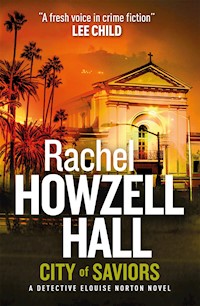

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: A Detective Elouise Norton novel

- Sprache: Englisch

Seventy-three-year-old Eugene Washington appears to have died in an unremarkable way - a heatwave combined with food poisoning from a holiday barbecue - but LAPD homicide detective Elouise "Lou" Norton is positive that something doesn't quite add up. Especially when she learns that the only family Washington had was his fellow church-goers. Lou is convinced that something wicked is lurking among the congregants. Could the murderer be sitting in one of those red velvet pews? And is someone protecting the wolf in the flock? Lou must force the truth into the light and confront her own demons in order to save another soul before it's too late.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 423

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also Available from Rachel Howzell Hall and Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Tuesday, September 1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Wednesday, September 2

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Thursday, September 3

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Friday, September 4

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

Saturday, September 5

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Sunday, September 6

46

47

Acknowledgments

Also Available from Titan Books

CITY of SAVIORS

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM RACHEL HOWZELL HALL AND TITAN BOOKS

Land of Shadows Skies of AshTrail of Echoes

TITAN BOOKS

CITY OF SAVIORS Print edition ISBN: 9781783296767 E-book edition ISBN: 9781783296637

Published by Titan Books A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd 144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First Titan edition: August 2017 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2017 by Rachel Howzell Hall. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

TITANBOOKS.COM

For Jill

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 1

1

THE THREE OFF-DUTY, RED-FACED COPS SEATED IN BROWN VINYL CHAIRS HAD BEEN broken—by guns, by fists, by life. And at eight o’clock in the morning, I sat across from them, in the sun-brightened waiting room of Matthew Popov, M.D. I harbored fractures, too—mine were as fine as cracks in a china cup that still held tea. But the trio didn’t see me or my cracks after their T&A check. Just their casts, their bandages, their bruised balls.

“Them kids just don’t get it,” crew-cut Darren complained. “It ain’t always about color. You look suspicious? I’m gonna stop you.”

The nerve beneath my left eye twitched, and the stress headache spilled across my forehead like warm milk. I snatched the month-old issue of People from the coffee table. One glance at the cover—BABY DRAMA FOR KIM—and I tossed the rag back into the swamp of “Divorce Looms for Jon!” and “Charlie’s Drunken Night!”

With my God-given tan, camel-colored pantsuit, and delicate ankles, I’m sure crew-cut Darren assumed that a computer keyboard had caused my job injury. Carpal tunnel syndrome from typing some true detective’s paperwork. What would he say if he knew that I was that Elouise Norton who had rammed a Toyota Rav4 into a Parks and Rec truck high above Los Angeles? That I’d fractured my left arm, cracked two ribs, and concussed my head in the process? That the monster who had killed Chanita Lords and other girls from my old neighborhood had flown through the windshield and chopped into pieces all because he hadn’t worn a seat belt on the way to the place he wanted to kill me? What would Darren say if he knew that I was that Elouise Norton?

Good job, Lou.

Why’d you do something stupid like that?

You got a death wish?

My phone vibrated from my bag—a text message. How was your appointment? Don’t forget we’re bringing breakfast on Saturday morning. See you then. Love u, Mom. She’d discovered emoticons, and now there were sixty pink hearts trailing “Mom.”

Haven’t gone in yet, I texted back. I’ll call later. Love u, too. Then, I tapped the Scrabble app.

Darren was now rubbing his tattooed left calf as he told Brad and Tony about chasing some banger-trash down Hoover Avenue. “Then, that summabitch hopped over the fuckin’ fence like Hussein Bolt.”

Tony laughed. “Usain Holt, dumb ass.”

Usain Bolt and you both are dumb asses.

“What the fuck ever,” Darren said. “I jumped over, too—that’s my point—and tore my ACL. Can you believe it?”

Out in the parking lot, a gardener wielded a leaf blower. Dead foliage and grit swirled around him like confetti. A garden party.

My phone vibrated again. Get felt up yet? Call me later. I have a proposition. My best friend, Lena Meadows, had also used emoticons—ones that my mother hadn’t discovered yet. A lipstick print, a martini glass, and a smiling purple devil.

I texted Lena back. A proposition? Doesn’t sound healthy nor wholesome. I rebuke you.

No message from Syeeda McKay, my other best friend. Or former best friend. Or . . . Relationship status: it’s complicated.

The door that led to the exam rooms opened. A doe-eyed blonde nurse called out. “Elouise Norton?”

In the vitals alcove, the nurse took my blood pressure (138/90), my weight (120 pounds), and my temperature (99.3). She cocked an eyebrow as she recorded the results in my chart. Then, she led me to the bathroom.

After peeing in a plastic cup, I followed her into exam room 8. I placed my bag in the chair, undressed, then pulled on a blue gown with thousands of ties. With nothing else to do but sit, I studied the posters on the walls.

DID YOU GET A FLU SHOT?

Nope.

LEARN THE TRUTH ABOUT HEART DISEASE.

Okay.

DO YOU HAVE POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER?

I gulped, then clamped my jaw before sending my gaze back to flu shots and clogged arteries. And I kept them there until Dr. Popov’s gray eyes bore into mine.

His wintergreen breath had almost covered the smell of coffee. “Your blood pressure’s up,” he said. “Has your pressure been high lately?”

I futzed with one of the ties on the gown. “No.”

His large soft hands tilted my head this way and that. “Have you been charting it with the machine I gave you?”

“Yes.”

“Are you in pain right now?”

My cheeks warmed. “No.”

Three lies told in less than twenty seconds. The Hussein Holt of Lying.

Dr. Popov consulted my chart. “You taking anything for the pain you’re not having?”

“Ibuprofen every now and then.” My nose ached from growing so much and so quickly. “I’ve been taking allergy meds. A lot of fires burning right now.”

“Your elevated BP is a little worrisome. Hasn’t been this high since I cleared you three weeks ago for normal duty.” The doctor squinted at me. “You smoke?”

“No.”

“You drinking?”

I cracked a smile. “What do you have?”

“Seriously. Are you drinking?”

We held each other’s eyes. My underarms prickled with sweat, and my upper lip twitched.

Dr. Popov sighed, then examined the last scars high above my right eye, my right ear, and behind my hairline. He pressed on the scalp wound, then held up his fingers. Blood. “You have to stop scratching that. It starts to scab, but then . . .”

“I keep forgetting it’s there,” I said. “I’ll stop. Promise.”

“Does it still hurt?”

My eyes watered as though his fingers were still pressing the wound. “No.”

“You sure? I see tears.”

“Allergies because of all the fires.”

“You didn’t take anything this morning?” he asked.

I shook my head. “Didn’t want to compromise my urine test.”

“We can tell Claritin from Percocet. The miracle of science.” Then, he lifted my left arm.

A dull twang spun in my shoulder like a pinwheel.

“You winced,” he said.

“Sore from physical therapy.” I smiled. “And I’m back in Krav Maga for strength training.”

True, and true.

My phone caw-cawed from the inside of my bag—the eagle ringtone for my partner, Colin Taggert.

“When you’re sore like this,” Dr. Popov was saying, “what do you do?”

“Heating pad and Icy Hot,” I replied. “Long baths and hot showers.”

After promising to lower my numbers through clean living and exercise, and after receiving a flu shot, I trudged to the scheduling desk where the doe-eyed blonde nurse pulled up a calendar to schedule my next visit.

The eagle caw-cawed from my bag again. This time, I answered. “Happy Tuesday.”

“It’s not even nine o’clock yet,” Colin complained, “and it’s already eighty-six degrees.”

A heat wave now roasted Los Angeles—yesterday, we hit 103 degrees in the Valley, 94 degrees downtown, and enjoyed 80 percent humidity, courtesy of a hurricane currently destroying Baja California. Fires to the north of us, fires to the south of us, fires to the east of us. All we needed was an earthquake and a Sig Alert on the 405 freeway to complete the “Seasons of LA” bingo card.

I stepped away from the scheduling desk and wandered to a corner. “What’s up?”

“All these fires are making my eyes itch,” Colin whined.

“You use the drops I gave you?”

“No.”

“Then stop complaining.”

“We’re on deck,” he announced.

“Just when I was about to go out on the yacht.”

“So, you’re driving to 8711 Victoria Avenue, off Crenshaw and Vernon.”

“What’s today’s special?”

“A suspicious death. An old guy dead in his old house.”

“Dead, you say?”

“Seniors are droppin’ from the heat. It’s like we’re standing on hell’s patio.”

I gave the doe-eyed blonde nurse the “one minute, please” finger, then said to Colin, “Old guy, old house, no A/C probably. Nothing suspicious about that. This shouldn’t take long.”

“You’ll get to go out on the yacht after all,” he said.

I scheduled my next appointment for October 2nd, then left the medical office of Matthew Popov, M.D., with a bloody wound in my hair, sparks shooting in my shoulders, and sparks shooting at the base of my skull.

I was healed.

At the lobby gift shop, I purchased a bottled water and a morning bag of Doritos (baked Doritos: my first step toward clean living). By the time the elevator stopped at P2, I’d already popped four Advil and a Claritin. I stepped out of the air-conditioned car and into the muggy underground parking garage. My eyes flitted from dark corner to darker corner. Shadows. Weird echoes.

A man stood . . . by the . . . ? What is he . . . ? He looks like . . . him. But’s he dead. Right?

That’s what I’d been told. That’s what I’d read. But those seconds before the crash . . . couldn’t remember.

I darted to my Porsche Cayenne with my heart pounding, my nerves frayed, my lungs pinched so hard I could barely breathe.

The same state I’d been in when I first arrived.

That shadow moved . . . The man, his shadow . . .

No. Don’t go there. Just the wind. Dr. Bernie Shankman’s soothing baritone filled my head. Just the wind blowing, Elouise. Just the wind. Take a breath. Take a breath.

I reached my car, panting as though I’d run a mile in a minute. Knees weak, I leaned against the car door with my eyes squeezed shut.

Your pounding heart? That’s the wind. The scent of a man’s cologne—but it smelled like his cologne—that’s the wind, too. Just the wind, Elouise. Breathe. Breathe.

Second time in an hour that I’d employed visualization to coax me off the ledge.

And now, in my mind’s eye, I reclined in a chaise surrounded by palm trees. I was relaxing on my favorite Big Island beach. The breeze lifted my hair and ferried the aroma of Lava Lava Club’s sticky-sweet drinks and pineapple-fried rice. Waves. Fluffy white clouds. Blue sky. Quiet. So quiet.

“Open your eyes,” I whispered.

I was still hunkered in the dark parking garage. But there were no ghosts now. No shadowy man in the corner. No Zach Fletcher.

Yet.

2

DR. SHANKMAN’S RELAXATION TECHNIQUE WORKED. EVEN AFTER A THREE-MINUTE conversation with my mother, Georgia—how’d it go, what did he give you, do you need to take it easy, do you still like bagels?—my breathing had slowed, and my hands had lost some of their clamminess. But then that clamminess could’ve been caused by the weather.

It was ninety-six degrees at nine thirty, and Colin was still complaining to me over the radio about the heat. “The end times are upon us,” he said, “but no one cares except for the boy from Colorado Springs.” He was right—Angelenos had no fucks to give.

The city was up and at ’em. Cars and buses swooped up and down Crenshaw Boulevard. Old ladies pushed rickety carts to the Laundromats. Pods of day workers loitered at the U-Haul store. Just a few years ago, the space shuttle Endeavor had traveled on this wide, tree-lined street. Smiling people of all shades of brown had waved at astronauts, the mayor, and other VIPs. Crenshaw High School’s marching band had jammed for us as we tucked into Styrofoam containers of Dulan’s smothered chicken and black-eyed peas.

“Happy black people and rocket ships,” I said, remembering that afternoon.

Colin chuckled. “God bless America.”

“That’s all about to change,” I said.

He shouted, “The white folks are coming! The white folks are coming!”

And they were. Paler faces now cruised the aisles of Ladera Heights supermarkets, the mall in Culver City, and the hiking trails off Stocker Avenue. The new subway line would rumble beneath Crenshaw Boulevard to the airport. The Santa Barbara Plaza, where my sister Victoria was last seen alive, was now home to heavy equipment bulldozing dilapidated hair salons, night clubs, and art galleries. Replacing it: a new 8.6-acre medical facility.

“And why wouldn’t we come?” Colin asked. “Rent’s too damned high where I’m supposed to live. Just think: hundreds of coffee shops and benches everywhere. A Trader Joe’s. Yoga studios. All kinds of white-people shit.”

“Hooray. Bringing with them more ways to stay broke.” I turned right at the 7-Eleven, then made another left onto Victoria Avenue.

The street had been blocked by cop cars with swirling lights, fire trucks with swirling lights, an empty ambulance that had turned off its swirling lights—never a good thing for folks who had called EMTs.

“You go in yet?” I asked Colin.

“Nope,” he said. “Wanna share those first moments with you.”

A firefighter in dingy yellow pants and galoshes vomited on the sidewalk. Seeing that made me sit a little longer in the car.

Colin, tanned and big-eared, weaved past the parked emergency vehicles to approach my SUV. He wore the too-small blue shirt with the stubborn taco-sauce stain on the cuff—a shirt he refused to toss because a cute assistant district attorney said the color brought out his eyes. And now he saluted me, then clicked his heels. “What’s up, Sarge?”

My promotion to detective sergeant wouldn’t make the dead man inside 8711 Victoria less dead or more alive. I rolled down the driver’s-side window and stared at the sick hero. “Umm . . .”

“What’cha waiting for?” Colin’s gaze followed mine. “Oh yeah. That.”

“Why is he doing that? Vomiting?”

Colin shrugged, but the vein in his neck jumped. Liar. He knew something.

With ice in my belly, I climbed out of the car.

“The heat,” I said. “That’s probably why he’s throwing up.”

“A fireman not used to dead people in the summer?” Colin asked. “Sure: I’ll take that answer.”

Fifties-era California bungalows with square angles and wide lawns lined the block. A McMansion had been shoved into every fifth lot—an elephant crammed into a zone designed for zebras. Sunlight glinted off glass, chrome, and the badges of patrol cops gathered on the sidewalk and made Victoria Avenue disco-ball bright.

“I used the eye drops,” Colin said.

“Better?”

“Yep, but looking at this place, it’s not gonna matter much.”

This place. A dingy yellow Craftsman with wide eaves, a raised porch, big windows . . . and a junk pile beneath the colossal magnolia tree. Another pile of junk blocked that raised porch. Another heap almost hid the rusted gray Chrysler Le Baron. Old toilets. Broken who-knows-what. Flashes of fluffy pink this and plastic black that. A breeze thick with the stink of dead things and animal urine. Weeds and large yellow dandelions sprouted between the occasional gaps of trash. Some of the junk within the piles . . . moved.

“Cats,” Colin explained. “Cats and their enemies.”

I slipped off my blazer. “Enemies—you mean mice?”

“Rats. And then, the raccoons come. They mostly come at night . . . mostly.”

I swallowed. “Tetanus and rabies and . . . Aliens would be cleaner and . . . My lord, what are we about to see?”

The four uniforms gold-bricking beneath the magnolia tree glanced in our direction. Then, they whispered to each other.

My ears burned—the side eyes and gossip involved me.

“Fitzgerald, one of the jerk-wads over there,” Colin said, nodding toward the klatch, “he’s the R/O.”

I grabbed my leather binder from the passenger seat. “He’s doing the best he can with that tiny brain of his.”

Tavaris Fitzgerald turtled toward us, passing a rusted toolbox, a tangled nest of wires, and an abandoned air-conditioning unit. He wiped his sweaty brown face with his wrist, then gave Colin the “what-up” nod. He regarded me as though I’d eaten the apple fritter he’d been saving all day.

“Who’s our special guest this morning?” I asked him.

Fitzgerald flipped open his steno pad. “Eugene Washington. Lives here alone. A Bernice Parrish”—he pointed to the closest radio squad car, where a pair of thin brown calves ended in feet clad in dusty gladiator sandals—“found him in the den around seven fifty this morning. She claims to be his girlfriend. Has a key to the place. Anyway, EMT got here about ten minutes later, pronounced him dead, and they’ve been throwing up ever since.”

The now-recovered fireman was patting the back of another vomiting hero.

“And we’re here because . . . ?” I asked.

“The EMTs found a gun near the body. No obvious bullet wounds, but . . .” He shrugged. “It was there and we can’t ignore it.” Suspicious death? Sure.

“You talk to anybody other than Bernice Parrish?” I asked Fitzgerald.

“Nope.”

“Anybody other than you and the EMTs enter the house?”

The patrol cop smirked. “You don’t have to worry about lookie-loos going off in there.” He eyed my silk blouse, my slacks, and loafers. “Must be nice.”

My face flushed and I cocked an eyebrow. “It is nice, thank you. Anything else?” Would he dare speak those words he had whispered behind my back today, and many days before? Crazy bitch. Suicide queen. Ass kisser. Dick sucker. Would he? Fitzgerald had never liked me—to him, I thought I was “all that” with my B.A. and J.D., my Porsche and silk blouses. To him, I wanted attention so much that I’d hurled myself and a small SUV into a parked truck. I had used my boobs and color to be promoted from patrol to detective and, now, detective sergeant. Overrated. Underserving. Two full scoops of cray-sins. And he was not only a member of the Screw Lou fan club—he was also the president.

Please do it. Please say something. A bead of sweat slipped across the scar above my eyebrow. The sting made me grimace and pissed me off just a little bit more.

But Fitzgerald knew better than to insult a woman packing two guns on a hot day. He said, “Vic’s in the den,” then turtled back past the toolbox, past the wires and past the air-conditioning unit to reach his posse beneath the tree.

“All that sexual tension,” Colin said as he doused two handkerchiefs with Aqua Velva. “Thought you were gonna take him behind the house and make him a star for three minutes.”

I took a hankie from him. “Well, I’m glad you stayed. If we’d been alone, I would’ve straddled him on top of the rotten mattress over by that hill of cat poop.”

Colin and I zigzagged through metal tubes and broken Igloos, very dead felines and moldy cardboard boxes. We bounded up the porch’s rickety stairs, passing four very alive cats now chillin’ on banisters as though visits from homicide detectives occurred every Tuesday at nine thirty. After signing in with a round female officer who obviously had no sense of smell, I pressed the cologne-soaked hankie against my nose and stepped across the threshold and right into the living room.

Two grubby, mustard-colored armchairs faced a cold fireplace and an entertainment center holding a thirty-inch television and a VCR. Dusty paintings of lighthouses, countryscapes, and sad clowns hung lopsided on the walls. Dark crown molding, natural light, and hardwood floors in a moderately clean house would’ve made the cottage-cheese ceilings tolerable. But the worrisome . . . everything else—from the rotten carpet and the moldy walls to the vermin—was nowhere in the realm of tolerable.

“Wow,” Colin said.

With the handkerchief to my face, I used my other hand to work my mini-Maglite around the room. “I spy, with my little eye . . .”

“Tetanus,” Colin said.

“You said tetanus outside.”

“Fine. Hantavirus. My turn. I spy, with my little eye . . .”

Atop the stack of boxes near the fireplace, a gray momma cat licked two skinny kittens nestled in her paws. “I spy feline HIV.”

We moved down a dim hallway crowded with sagging boxes of vinyl record albums, mildewed stacks of Reader’s Digest, clothes on and off hangers, beer bottles, and plates and bowls in various states of dirty, filthy, and broken. Something crunched beneath my loafer—and it wasn’t dirt.

My calm was starting to flake off like old paint. With a shaky hand, I pushed the hankie harder against my nose. “Glad I had Doritos for breakfast.”

The funk of bad meat, abandoned fruit, and forgotten eggs intensified with each step. In the kitchen, dishes piled high beside thousands of empty tins of cat food, plastic milk containers, and food wrappers. Cats and clutter filled every drawer and cabinet. Two cats perched atop the fridge—the orange one had no right eye, and the gray one was just a bag of bones.

In the den, the heavy green curtains had remained closed since John Lennon’s murder, and the folds in the fabric had petrified. None of this bothered Eugene Washington. Dressed in green and gray flannel pajama bottoms and a gray wifebeater, he sat in a stained plaid armchair surrounded by old newspapers, fast-food bags, soiled boxers—and a Smith and Wesson revolver. He no longer watched the Judge Mathis episode now playing on the ancient floor-console television—his eyelids had swollen shut.

The TV’s shoebox-size remote control sat on the old man’s right thigh. His right hand, covered in red welts, had clenched into a tight fist. Froth had dried on his swollen tongue now stuck between swollen blue lips, and blue splotches now colored his freckled butterscotch complexion. No blood anywhere from a gunshot wound. And a gun that big would’ve left its mark all over the place. Blowflies darted around his gray hair and beard. A silver cat sat atop the television, waiting.

Gee. And Dr. Matthew Popov had thought that red wine played a major role in my high-blood-pressure woes.

“At least we got here before the cats started nibbling,” Colin said. “Cats don’t care about jack when it’s time to eat.”

I aimed the flashlight’s beam at the man’s swollen blue face. His tongue, also enlarged, stuck out from between his crusted lips. “No maggots yet. No decay. Did he eat something?”

On a rusty tray beside the armchair, I spotted a half-empty forty-ounce bottle of Schlitz and a white casserole dish with blue flowers around the rim. Inside the dish was something goopy—and delicious to the roaches now stuck there. Other roaches sprinted in and out of the malt-liquor bottle and swarmed over their dying compatriots trapped in the casserole dish.

And the flies. Oh, the flies. Their buzz competed against the TV plaintiff named Cinnamon now yelling at Judge Mathis about the money being a loan and not a gift.

“I can’t . . .” Colin stumbled backward, bumping against plastic milk jugs filled with worrisome yellow liquid.

The fumes of cat urine, dust and dander, and dead things made my eyes tear. Made it damn-near impossible to study the dead man before me.

There was no inhaler, no EpiPen, and no medic alert bracelet on Washington’s wrist—objects often found near those with asthma or known food allergies.

I aimed the light at the man’s left bicep.

The blue-black ink of a tattoo. TO HELL AND BACK 66–69 VIETNAM.

The cologne’s atoms gave up and the protective power of the handkerchief disappeared. My gag reflex awakened, making me back away from Eugene Washington. With my stomach roiling, and knees threatening to dump me into a mound of fur and bones, I stumbled through the maze of trash and back out into the hot, still air.

To hell and back.

3

YOU WILL NOT VOMIT.

I tripped to the front porch. Found stability by crouching against the rotted wood banister. Willed myself to swallow spit and bile.

You will not vomit. Not now. Not in front of them.

I hid my face in the crack of my arm, and whispered, “Just the wind. Just the wind.”

“I damn-near endoed off the porch.” Colin’s gravelly voice scraped against my tender nerves. “But almost breaking my neck kept me from hurlin’ all over the—you okay, partner?”

Still flustered but less gaggy, I forced myself to stand. “I’m good.”

It was hot and mean out here, but there were no crummy ceilings or dead men. At least.

Fitzgerald had slicked yellow POLICE LINE—DO NOT CROSS tape through the property’s white picket fence. His partner, Monty Montez, doubled up with bloodred CAUTION BIOHAZARD tape to drive the point home. Here there be monsters and dragons and roaches and all kinds of bloody bogeymen that you can’t get off your shoe soles or out of your mind.

Neighbors stood behind the tape with their arms crossed and their faces wet with sweat. Most held phones to take pictures and video. No one cried—a strange thing. Typical crime scenes came with their own soundtracks: wails to the heavens, curses at cops, why oh why lord and that’s my momma in there.

This scene’s soundtrack featured the gags of men, the splatters of vomit, and the purrs of cats. Tetanus and mesothelioma were silent killers.

“Being inside that house . . . that was simply remarkable.” I blew my nose into the handkerchief, clearing it of insect eggs and vaporized cat poop.

“So?” Colin asked.

I rested against the banister. The urge to puke warmed my ears again. “So, what?”

“No dead people speaking to you, telling you who done it? No shining? No ghost-whispering?”

“The gun’s odd, but I see no blood. Plus, he’s old, it’s a hundred and thirty-eight degrees today, and there’s cat shit and asbestos and jugs of pee everywhere. He’s supposed to be dead. We’re supposed to be dead, goin’ off in there unprotected.”

Colin gaped at me. “But . . .”

“I get it: You want me to point to the mold on the wall-paper and say, ‘Aha! Those spores originate in the mountains of Bolivia, so, someone must’ve planted them there two years ago to slowly kill him.’ That’s what you want?”

Colin’s mouth moved, but no words came. Finally, he said, “Yeah. That’s what I want.”

“Give me a minute, then, all right? It’s a hundred and thirty-eight degrees today.”

A moment later, Fitzgerald and the other uniforms huddled with Colin and me on the porch. “No one goes back in there yet,” I instructed. “We still need to figure out what happened. Let’s put up a tarp, though, to shield the door. And from now on until forever, we’ll wear full protective gear, top to bottom.”

Break!

“Call the M.E.,” I told Colin, “and call Zucca, too, if you could. I’ll go chat with the girlfriend.”

“So, you think this is murder?”

“Good question,” I said, walking away from him. “Call Zucca, okay?”

Did someone kill this man? Had he been shot and we just couldn’t see the fatal wound from our vantage point? Did he die from the heat like most of the other old people around the city and the gun just happened to be there—like the other countless pieces of crap near that armchair? Or had his lungs simply filled to capacity with dust and decided not to work anymore?

Even though my head said, “natural death,” my gut said “murder.” Because I knew Death—we were homies. Closer than close. Heart attacks, strokes, hypothermia—not my domain. Strangulation, gunshots, decapitations, stabbings? That was me, all day.

Once a medical examiner arrived and took possession of the body, I’d get to find out which part of me—brain or gut—would reign supreme until the next case.

Bernice Parrish sat in the front seat of Fitzgerald’s squad car. Her bloodshot eyes flicked between the badge on my hip, her dead boyfriend’s house, and the screen on a cell phone that matched her Pepto-pink shorts set.

I introduced myself, remembering to say “sergeant” now instead of “detective.”

“I ain’t done nothing,” Bernice Parrish snapped.

“I ain’t said that you did,” I snapped back.

This woman knew her way around a rat-tail comb, edge-control gel, and curly Remi hair extensions. Her hard brown eyes suggested that she was just twenty-seven years old, but her calloused and scarred hands told the truth: mid-to-late fifties. She rocked in the car seat and fanned at her face with those middle-aged hands. Beads of sweat pebbled on her hair like morning dew on vines. “Lord Jesus Father God,” she whispered. “Be with me, be with me, Lord. It’s too damn hot today.”

“I totally agree. It is too damn hot today.” I opened my binder. “Your full name, ma’am?”

“Bernice Parrish. That’s with two Rs.” She lived in Inglewood, across the street from the Forum, and owned a hair salon over on Market Street. “Who Do Yo Hair,” she said.

I blinked. “Umm . . . Her name’s Herschelle, and she’s over on—”

Bernice Parrish sucked her teeth and rolled her eyes. “No, sweetie. That’s the name of my salon. Who Do Yo Hair.”

I smiled. “Oh. Got it.”

She squinted at my ponytail and fringed bangs. “Sweetie, I ain’t mean to be rude, but you needs a trim.”

I flushed, and millions of pins pricked my warm cheeks. “I know. It’s been a while.”

“You on some drugs?”

“Excuse me?”

“I can tell.” She pointed at my head with one copper-polished fingernail, then used that finger to flick at my bangs.

I tensed and came thisclose to breaking her hand. “Ma’am, you need to remove your—”

“Drugs always come out in the hair. Makes it dull and brittle. Tell her to give you a protein pack after your next relaxer. Then, she need to follow it with a clear cellophane. And then, she gotta give you a good trim. You gotta get that stuff off before you go bald.”

“I’ll tell her next week when I see her. Thank you.”

She frowned, shook her head. “A man put his hand up in there, he likely to cut his finger off.”

This morning, a man did have his hands up in my hair. But the blood on Dr. Popov’s fingers had been mine.

“Cuz you look nice with that suit,” she was saying, giving me the up and down. “I saw something just like it at the Walmart over in Torrance. Is that where you got it? At the Walmart?”

I forced a smile. “How did you know Mr. Washington?”

“He was my boyfriend.”

“How long were you dating?”

“Six months or so.”

“He lives here alone?”

She snorted. “He did, if you don’t count all them cats.”

“How old was he?”

“He just turned seventy-three yesterday.” She craned her neck to look at the house. The sweat pooling in the scoop of her clavicle trickled down her breastbone. “When y’all gon’ let me go in? Gene left me something.”

I lifted an eyebrow. Too soon, Bernice. Too soon.

“It’ll be a moment, ma’am,” I said. “Tell me how you came to find him today.”

“Every Tuesday,” she said, “I help him straighten up a bit. And today is Tuesday.”

I paused before saying, “Straighten up . . . what?”

She cocked her head. “The house. What you think?”

I pointed at the yellow house behind me. “That house?”

“Yes, that house.” She narrowed her eyes as Fitzgerald and Montez unfurled a blue tarp at the foot of Washington’s porch. “Folks from church gon’ be coming by soon, takin’ stuff when Gene told me—”

“No one’s going in, okay? Now: you got here at what time?”

“Around seven fifty. I used my key to get in.” She fished around her stained suede bag. Pulled out a key ring that held a crucifix the size of a freeway sign, an I HEART JESUS fob, and a mini bottle opener. “I stepped in and shouted, ‘Gene—,’ ” she yelled.

I startled and almost dropped my pen and binder.

“ ‘Gene,’ ” she shouted again, “‘where you at?’ And then I smelt it.” She sprang up out of the passenger seat and pinched her nose. Standing, she wasn’t that much taller. “It usually stank off in there, especially with all them cats. But this stink was different. Extra cheesy smelling. And sweet. Like . . . old sticky cherries mixed with Parmesan cheese. You know what I’m sayin’?”

Impressed, I nodded. “Did you touch him?”

“Oh, hell no. Not with all them bugs crawling everywhere. Gene said I could officially have his—he called ’em his ‘soup pennies.’ ”

“What’s a soup penny?”

“You know, bullion coins? Bouillon is soup, ain’t it? And pennies are bullion coins. Soup. Penny.” She laughed. “He had a way of naming things interesting. But he said that they’re mine. He wrote all that down somewhere. Officially.”

“In a will?” I asked.

“That’s right,” she said with a cocked chin. “Back in July, our church, Blessed Mission over on La Brea, had a will-making seminar and we was all required to go.”

“We?”

“Anybody over fifty-five. See: white folks do their wills and be-hests and all that, but we black people, we wanna bury our money in the ground with funerals and don’t take care of our family. But with a will, everybody know they been taken care of.”

With numb fingers, I was writing all of this into my notepad.

Bernice Parrish had just uttered one of the most magical words in a possible homicide investigation: WILLS.

“This required seminar,” I said, “is that where you saw Mr. Washington making his will?”

The proprietor of Who Do Yo Hair grinned like a dwarf who’d just discovered a mine. “Uh huh. He got all kinds of stuff off in there, just sittin’. And most of it officially belongs to me now. He told me so. I just need to find where he put his will at.”

“When was the last time you saw him alive?” I asked.

She sat back down in the squad car. “Our church picnic on Sunday evening, over at Bonner Park.”

Bonner Park. Tiny razors cut up and down my spine. Even though I had no memory of it happening, I knew that I’d been rolled away on a gurney after my last visit there.

“Sister Elliott drove the church van,” Bernice Parrish was saying, “so she picked him up and brought him since Gene don’t drive no more. The picnic was really nice this year. We had a lovely time. Played dominoes, spades—you know how we do. People made potato salad and chicken, ham and lemonade. We ate a little bit of everything. Best thing was, way up in the park, you didn’t feel all scratchy-eyed from the fires over in the mountains.”

Mention the gun? Nope—I’d keep it in my pocket just in case Bernice had used it and hadn’t realized that she’d left it behind.

“You cook for him recently?” I asked.

“You askin’ if I made that cobbler he was eating?”

“Is that what that was?”

She pushed moist strands of hair from her face. “Uh huh. Peach cobbler. But no, I ain’t made that.”

“You said . . . peach?”

“That’s what it look like to me.”

“You know if anyone else who went to the picnic got sick?”

“I ain’t heard nothing about people getting sick.”

“Does he have a food allergy?”

She closed one eye as she thought. “He eat nuts all the time.”

“What about shellfish or mangoes or milk? Wheat, maybe?”

She shrugged. “To be honest, I don’t pay much attention to what Gene eat and don’t eat.” She jiggled her knee, then glanced past me to look at the house again. “How did he die?”

“We’re not sure,” I said. “Could’ve been the heat. Where did he get the peach cobbler?”

She shrugged. “Gene freezes a lot of stuff. That cobbler coulda been made back at Easter. I coulda made it. Sister Green coulda made it. Don’t look like my dish, though, with them blue flowers.”

“You touch that dish?”

“No.”

“I’ll still need your fingerprints.” For the dish and the gun.

“My fingerprints are gonna be all over that house.”

“Right. That’s why I need them.” I shrugged and smiled. “So did you hear from him at all yesterday?”

“No,” she said, fanning her face again. “He usually shut himself in on Mondays, especially after being in church and then going to the picnic on Sunday. He get cranky, and so I leave him alone until Tuesdays. He ready to see me on Tuesdays. I give him a trim and a shave, fix him some lunch and dinner for the week, straighten up a bit, do our thang, you know?”

“Did he have health problems?” I asked.

“Gene just had his physical last week for his new insurance policy—he hadn’t been to the doctor in ages.” A far-off look filled the woman’s eyes. “The doctor said he had high blood pressure. That’s about it. He was supposed to get some blood work done but never got around to it. But he ain’t ever complained about feeling bad. He was in high spirits on Sunday, sayin’ that he was about to come into some money, and he wanted to take me to Fiji to celebrate his birthday.” Her wet eyes glimmered with joy, and a smile softened her hard face. “And I kissed him, and I told him, ‘Gene, just tell me when to pack,’ see, cuz I always dreamed of—”

A sob burst from her mouth. She flung her head back and threw her hands in the air. “I can’t believe he’s gone. He’s gone, Lord. That ol’ buzzard . . . He left me. Why he leave me, Lord?”

She flapped her face as she dropped back into the passenger seat of the patrol car. Finally, she took a deep breath and slowly released it.

“You okay?” I asked. “You need a paramedic?”

She shook her head. “I’m fine.” She dried her cheeks with the heel of her hands, then said, “So, Officer, when y’all gon’ let me in?”

4

ALIVE ON SUNDAY EVENING. DEAD BY TUESDAY MORNING. NO DECAY. NO MAGGOTS. Peach cobbler and Schlitz malt liquor for a last supper. A fortune-hunter girlfriend.

“So, what?” Bernice Parrish asked me. “Two, three hours before y’all let me in to get what’s mine?” Her voice sounded flat. Her tear ducts were drier than all of California.

Not a good look, especially to murder police.

“Not sure yet when I’ll be able to let you in,” I said. “Stick around a bit, though, just in case. And give me your address and phone number. Someone’s gonna take your fingerprints so that we have them on file. You’ve been inside Mr. Washington’s home—you know what we’re dealing with, what we’re up against.”

She snickered. “Sweetie, you ain’t gotta tell me.” Then she recited her address again, and corrected me twice on the proper pronunciation of ‘Arbor Vitae,’ her street’s name.

“I know you have a key,” I said, “but you cannot go in until I say you can. Understand?”

She sucked her teeth, then nodded. “I got it, Officer.”

I thanked my first person of interest, then trudged back to the front yard.

Cats darted, crept, and skirted around the towers of trash. High in the sky, that white ball of death, now in its ten o’clock position, pounded the city, and the ibuprofen I’d taken in Dr. Popov’s elevator had quit me—every vulnerable nerve burned, from the wound hidden in my hair to the small callus on my left pinky toe. I needed to pop another Advil, but there was no popping-pill privacy. And Tavaris Fitzgerald hunkered beneath the giant magnolia with his eyes pecking at me like a backyard chicken. He’d sound the alarm if I popped a Luden’s.

“Keep an eye on Miss Parrish over there,” I told him. “Make sure that she stays.”

“She’ll be pissed off,” he said.

“Yeah, well, we’re all frustrated.”

“She under arrest, though?”

I squinted at him. “No, she’s not under arrest, but the day’s still young.”

Colin and I reunited to walk the perimeter. As we climbed over stereo speakers and televisions and hopped over bricks and wooden beams, I recounted my conversation with Bernice Parrish.

“Soup pennies?” Colin said.

“What the hell does that mean?”

“Soup is to bouillon and bullion is to gold. Penny is to coin and—the struggle is real with the heat, all right, so just go with it, damn.”

“Fine. So gold coins—that’s why we’re looking for clues in a junk pile?”

“For that, for his will, and to be sure that no one hid a bottle with a skull and crossbones label on it.”

“Coulda been regular old food poisoning,” he said. “Back in the Springs, when I was twelve, thirteen years old, there was a church picnic and the entire congregation got sick from Sister Perry’s ambrosia salad. For real: puke and shit everywhere. I got sick. My mom got sick. The pastor and his wife got sick. After that, Dad put the kibosh on us eating other people’s food. Fly, fight, win—you can’t do that if you’re crappin’ and hurlin’ everywhere.”

“We didn’t do church much after Tori disappeared,” I said. “We went a few times asking for their help, but we stopped. Mom said that she’d rather be a miserable failure in private. And all those special prayers and laying on hands just got to be embarrassing. Not that any of it worked in the end.” Sadness had lodged in my throat next to the buildup of asbestos and cat hair.

But forensics would make it all better. Maybe.

Lead criminalist Arturo Zucca looked far too relaxed. His black hair touched the tops of his ears; his shoulders sloped and rested in their natural position. The side effects from three weeks of vacationing in Turin. Zucca had witnessed countless strange things around this city, and I had stood beside him on many of these occasions. No shocks. No surprises. But now this veteran of horrors gawked at the mess before him as though Ed Gein, Leona Helmsley, and the Blob were all bathing together in a rusted tub of raw eggs and ground pork.

“Today, you become a man,” Colin announced.

“And if you need help during the journey,” I said, “you’ll probably find a pair of dusty balls somewhere in that pile of rusty nails near the tower of beer cans.”

Eyes wide, Zucca turned to me. “You’re . . . kidding about this. I’m . . . ?”

“Excited?” Colin asked.

“Challenged?” I suggested.

Zucca sighed. “I wanna go back to Italy.”

“Brooks is on his way,” I said. “In the meantime, let me give you a personal tour of the premises.”

Assistant criminalist Krishna Houzanian hadn’t torpedoed a crime scene in six days. But ability now took a day of rest as the blue-eyed bottle blonde half-assed stapled plastic sheets to the beams of Washington’s front porch. “What?” she snapped at me. “I’m setting up a staging area.”

I whipped my head around to glare at Zucca. “Dude. Really?”

“Sorry,” Zucca said to me, red-faced. “Krishna, get a real tent and set it up on the side of the house, along with a covered plastic path leading to the front door. Thank you.”

Krishna rolled her eyes, yanked off the plastic, then smartly got the hell out of my way.

Colin pat my shoulder. “You didn’t Ike Turner her. Guess therapy’s working.”

I grinned. “Today, I choose to embody our core values, partner. Krishna’s trying to force me to disrespect her. Nope. Not this time.”

It took Krishna only ten minutes to set up the staging tent. In the realm of homicide investigations, ten minutes equated ten hours—and a year from now, a defense attorney would make hay of the time span during cross-examinations. And I planned to blame it on her being born a Leo and a general-purpose basic bitch. The judge and jury would certainly understand.

At most crime scenes, homicide detectives didn’t slip into bunny suits. On this occasion, though, because of the miserable conditions inside the Washington house and the rapidly deteriorating state of its owner, I decided that I’d given enough of myself to the job. Bunny suits for everyone!

The staging tent offered enough space for three people but no space for any air or privacy. Quiet and dark, it was still a nicer retreat from the sun.

Colin stepped into a white Tyvek suit. “Bet when you rolled out of your empty twin bed this morning, you didn’t think you’d be doing this today.” He tugged at the zipper. “I need a suit with a bigger crotch.”

“A bigger crotch and a bungee cord to yank you from the pit of your delusions.” I stuck one of my loafers into the suit’s built-in booties, then eased my hands through the armholes.

“So, Sherlock,” Colin said, “how did Miss Bernice kill Eugene Washington?”

“She slipped something into his beer and/or his peach cobbler. Notice how she can’t wait to get off in this piece of crap house?”

Colin handed me a full-face respirator. “Why would a woman date an old man who lives in a filthy house?”

“Hidden treasure has led many women to do the unthinkable. Consider Anna Nicole Smith, Rupert Murdoch’s wives, et cetera. Shall I continue?”

Colin breathed heavily through his respirator, then said, “Luke, I am your father.”

“Low hanging fruit, Taggert. How about this?” I took a deep breath from the respirator, then said, “Shut up! It’s Daddy, you shithead! Where’s my bourbon?”

Colin blinked at me.

“Dennis Hopper, Blue Velvet?”

Colin shrugged, shook his head.

“One of David Lynch’s best films?” When he shrugged again, I shouted, “Get off my lawn.”

Zucca stepped into the tent and grabbed a suit from the box. “What did young Mr. Taggert do this time?”

“Claims he’s never heard of David Lynch,” I said.

“Is he, like, some famous actor?” Colin asked.

We stepped out from the tent and walked the plastic corridor to the blue-tarped front porch. A few bug-eyed neighbors backed away from the barrier tape. Tyvek suits meant Ebola, contamination, and danger.

Over near my car, Luke and Pepe were climbing out of a dusty silver Impala. Pepe had recently interviewed for an open position with Internal Affairs, the cops that policed the police. I didn’t know how I felt about that. Okay, I did—I didn’t want him to leave my team and Southwest Division for a bunch of rules-spouting cubicle dwellers down at Parker Center.

“I’m still not sure why I’m here,” Zucca said. “It’s hot, and an old man died in his filthy house. It’s been happening all summer.”

“There’s a gun near him,” Colin said, “and money may be involved.”

“Hence, suspicious death,” I added.

Zucca pointed at Colin. “You said ‘may.’ ”

“And if his death were natural,” I said, “there should never be a ‘may.’ ” I nodded in Bernice Parrish’s direction. “She’s why you’re here.”

The woman now paced behind the yellow tape with the pink cell phone to her ear.

Colin smiled. “Thank her when you get a chance.”

“And if it’s natural,” I said, “and this ends up being a wasted trip for you, I’ll buy everybody an ice-cream sandwich. How’s that?”

“Exciting. This isn’t the best scene,” Zucca warned. “It’s gonna be hard to get good prints with all the dust and cats and dead things everywhere. I spray Luminol, everything’s gonna glow. And I can’t really set up a proper field lab cuz everything’s contaminated.”

I nodded. “There will be little yellow tents everywhere. Understood. Let’s just do our best, all right?”

Minutes later, we congregated at the front door. Everyone on Zucca’s team held fancy equipment: cameras, brushes, light meters, whizzy-wigs, and dumbledores. My crew wielded pens and pads, as though we were working at a simpler crime scene.

“So you thought the Chatman fire was bad,” I told the small team. “But this? We haven’t worked a hoarder scene quite like this.”

“Mr. Maghami,” Pepe said. “Over on Denker.”

“He hoarded dogs,” I pointed out. “Today, we have cats, trash, kitchen sinks, the yeti, and a Bermuda Triangle forming off the back porch. If you think it, it’s there, so please be careful and focus on solving this case. And wear protective everything at all times.”

“What are we looking for?” Luke asked.

“All official-looking legal papers,” I said, “especially a will and insurance papers. Also, look for medications, household poisons . . . I want everything around him—the Smith and Wesson, the goopy stuff, the dish that it’s in, the beer bottle, remote control, all of it. The coroner should be here soon to claim our victim. Once Mr. Washington’s gone, I want anything that had been beneath him, so use your fancy Dustbusters. There may also be valuables scattered throughout the property. Gold coins, jewelry, cash. Take pictures, log it, tag it, and bag it. Be thorough cuz who wants to come back into this house again?”

Luke raised his hand. Some people laughed.

Before disappearing behind the tarp and trekking back into the house, I glanced at Victoria Avenue.

People were taking selfies with the hoarded house behind them. And Bernice, phone still to her face, waved her free arm at someone down the block.

Zucca’s photographers wasted no time capturing on film the inside of the filthy Craftsman. Their cameras clicked and whirred as they murmured, “See that?” “Oh my gosh!” and “What the hell?”