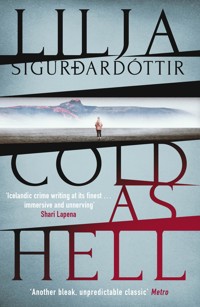

Cold as Hell: The breakout bestseller, first in the addictive An Áróra Investigation series E-Book

Lilja Sigurdardóttir

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: An Áróra Investigation

- Sprache: Englisch

Áróra returns to Iceland when her estranged sister goes missing, and her search leads to places she could never have imagined. A chilling, tense thriller – FIRST in an addictive, nerve-shattering new series – from one of Iceland's bestselling authors… 'Icelandic crime writing at its finest … immersive and unnerving' Shari Lapena 'Best-selling Icelandic crime-writer Sigurðardóttir has built a formidable reputation with just four novels, but here she introduces a new protagonist who is set to cement her legacy' Daily Mail 'Another bleak, unpredictable classic' Metro **Winner: Best Icelandic Crime Novel of the Year** –––––––––––––– Icelandic sisters Áróra and Ísafold live in different countries and aren't on speaking terms, but when their mother loses contact with Ísafold, Áróra reluctantly returns to Iceland to find her sister. But she soon realises that her sister isn't avoiding her … she has disappeared, without trace. As she confronts Ísafold's abusive, drug-dealing boyfriend Björn, and begins to probe her sister's reclusive neighbours – who have their own reasons for staying out of sight – Áróra is led into an ever-darker web of intrigue and manipulation. Baffled by the conflicting details of her sister's life, and blinded by the shiveringly bright midnight sun of the Icelandic summer, Áróra enlists the help of police officer Daníel, as she tries to track her sister's movements, and begins to tail Björn – but she isn't the only one watching… Slick, tense, atmospheric and superbly plotted, Cold as Hell marks the start of a riveting, addictive new series from one of Iceland's bestselling crime writers. ––––––––––––––––– 'Lilja Sigurðardóttir doesn't write cookie-cutter crime novels. She is aware that "the fundamentals of existence are totally incomprehensible and chaotic": anything can and does happen … Isn't that what all crime writers should aim for?' The Times 'Lilja is a standout voice in Icelandic Noir, and this book does not disappoint … Cold as Hell is her best yet' James Oswald 'Domestic abuse, high-finance hanky-panky, and illegal immigration all figure in this arresting series launch … sure to please Scandi noir fans' Publishers Weekly 'So atmospheric' Crime Monthly 'Intricate, enthralling and very moving – a wonderful crime novel' William Ryan 'Three things we love about Cold as Hell: Iceland's unrelenting midnight sun; the gritty Nordic murder mystery; the peculiar and bewitching characters' Apple Books 'Lilja Sigurðardóttir just gets better and better … Áróra is a wonderful character: unique, passionate, unpredictable and very real' Michael Ridpath Praise for Lilja Sigurðardóttir 'Smart writing with a strongly beating heart' Big Issue 'Tough, uncompromising and unsettling' Val McDermid 'Tense and pacey' Guardian 'Deftly plotted' Financial Times 'An emotional suspense rollercoaster' Alexandra Sokoloff 'Tense, edgy and delivering more than a few unexpected twists and turns' Sunday Times 'The intricate plot is breathtakingly original, with many twists and turns you never see coming. Thriller of the year' New York Journal of Books 'Taut, gritty and thoroughly absorbing' Booklist 'A stunning addition to the icy-cold crime genre' Foreword Reviews For fans of Katrine Engberg, Eva Bjorg Aegisdottir, Arne Dahl and Sarah Vaughan

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 378

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

i

Icelandic sisters Áróra and Ísafold live in different countries and aren’t on speaking terms, but when their mother loses contact with Ísafold, Áróra reluctantly returns to Iceland to find her sister. But she soon realises that her sister isn’t avoiding her … she has disappeared, without trace.

As she confronts Ísafold’s abusive, drug-dealing boyfriend Björn, and begins to probe her sister’s reclusive neighbours – who have their own reasons for staying out of sight – Áróra is led into an ever darker web of intrigue and manipulation.

Baffled by the conflicting details of her sister’s life, and blinded by the shiveringly bright midnight sun of the Icelandic summer, Áróra enlists the help of police officer Daníel, as she tries to track her sister’s movements, and begins to tail Björn – but she isn’t the only one watching…

Slick, tense, atmospheric and superbly plotted, Cold as Hell marks the start of a riveting, addictive new series from one of Iceland’s bestselling crime writers.

iii

COLD AS HELL

Lilja Sigurðardóttir

Translated by Quentin Bates

PRONUNCIATION GUIDE

Icelandic has a couple of letters that don’t exist in other European languages and which are not always easy to replicate. The letter ð is generally replaced with a d in English, but we have decided to use the Icelandic letter to remain closer to the original names. Its sound is closest to the hard th in English, as found in thus and bathe.

The letter r is generally rolled hard with the tongue against the roof of the mouth.

In pronouncing Icelandic personal and place names, the emphasis is placed on the first syllable.

Áróra – Ow-roe-ra

Ísafold – Eesa-fold

Björn – Bjoern

Kópavogur – Koe-pa-voegur

Keflavík – Kep-la-vik

Jonni – Yonni

Hákon Hauksson – How-kon Hoyk-son

Grímur – Grie-moor

Hringbraut – Hring-broyt

Lækjargata – Like-ya-gata

Gúgúlú – Gue-gue-lue

Hafnarfjörður – Hap-nar-fjeor-thur

Dagný – Dag-nie

Kristín – Christine

Bústaðavegur – Bue-stath-ar-vayguy

Reykjanesbraut – Rey-kja-nes-broyt

Hverfisgata – Kverfis-gata

Seyðisfjörður – Sey-this-fjeor-thur

CONTENTS

Down in the midst of the sharp-toothed lava, he regained his balance and reached for the hand that had slipped from the suitcase. It was as cold as ice. He should have expected it, but the chill and the lifeless feel of the hand came as a shock.

The tears forced their way from the corners of his eyes, and he whispered ‘I love you’ into the bright summer night, which seemed to have a tranquillity all of its own for the few hours around midnight, as if even the birds drew the line at staying awake all night long. His whispered, loving words were almost a sacrilege against the silence, so he didn’t repeat them, even though he would have preferred to shout them out over the lava field, to fill his lungs, and yell with all the power in his body and soul that he loved her. Instead, he crouched and laid his lips cautiously on the hand. He stayed that way for a while, and before he realised it, the warmth of his lips had passed into the back of the hand so that the skin appeared to have come to life. His lips moved over it as he kissed the cold hand again and again, kissing the knuckles, the wrist, the fleshy part of the palm that he had heard somewhere was called the Point of Remembrance, and the fingers, one at a time, until his lips touched something hard: the engagement ring.

He pulled at it, but the finger seemed bloated, and the ring refused to move, half sunk in the swelling that had enveloped the hand. He licked the finger and spat onto the ring, working it back and forth until it finally came off. He dropped it into his pocket and quickly kissed the hand once more, fighting back the desire to unzip the case to see the face one last time. He wanted to know if it had swollen, if it had taken on the same blue tinge as the hand. But at the same time, he had no desire to see what death had done to her beautiful face. Everyone knows that flesh loses its colour once the blood no longer flows, that a grey pallor takes over after a few hours. Death destroys everything.

He wiped away the tears and sniffed hard. Then he carefully 2pushed the hand back inside the case and zipped it shut. He climbed out of the fissure and looked down at the dark-red suitcase that lay in it, not right at the bottom, but caught on the jagged lava points. It was still out of sight, though, unless you stood right at the edge of the fissure and looked down.

This moment in the lava field marked a turning point in his life. Sorrow had left him devastated, but at the same time he felt a certainty in his chest that cut deep and pained him like razor-sharp steel. Now everything was different. He wasn’t the man he thought he had been. Now he knew he could kill.

WEDNESDAY

1

Disappeared. That was what her mother said on the phone, and Áróra could hear her voice crack in a way that never happened unless there was something serious going on.

‘Your sister’s disappeared,’ she said, and Áróra felt the old emotions return: fear and anger. It hadn’t been long ago that those emotions would have dragged her off the sofa, out to the airport and all the way to Iceland. But they wouldn’t do that now. Instead they were joined by the feeling that accompanied anything to do with her sister Ísafold, and that was fatigue.

‘Mum, she’s probably just too busy to answer the phone.’

Áróra knew that protest, or any attempt to wriggle away, was doomed to failure once her mother had her teeth into something, but she tried anyway. She had just switched on the TV to watch a repeat of Wire in the Blood, her favourite crime series, and had been looking forward to spending the evening on the sofa.

‘She hasn’t answered the phone for two weeks now. That’s too long to be normal. And Björn doesn’t answer either, and I can’t figure out from this online Icelandic phone book how to find any of his family.’

Áróra sighed, taking care not to let her mother hear.

‘Does her phone just not ring, or is it engaged … or what?’

‘Nobody answers their home phone, and when I call her mobile it goes straight to voicemail.’

‘And have you tried leaving a message?’ Áróra asked, and heard her mother bristle.

‘Of course I’ve left messages. Time and again, but she doesn’t reply to them. It’s the same with Facebook, as you must have seen – she hasn’t put anything new on there for more than two weeks.’4

‘You know she blocked me on Facebook, Mum. I don’t see anything she posts.’

It didn’t matter how often she tried to explain it to her mother, she seemed unable to take on board that there was no contact between the sisters.

Her mother sighed heavily.

‘Oh, sweetheart, don’t be like that,’ she said with the familiar tone of voice that told Áróra she was being difficult, even though everything she had said had been the honest truth. Her mother would never dream of criticising Ísafold for being difficult, for not answering the phone, for not being in touch. After Ísafold had left home, when she was around twenty, it was as if she had become some sort of iconic being, while their mother had continued to treat Áróra like a teenager.

‘Do it for me. Go to Iceland. Check up on her.’

‘All right,’ Áróra agreed, and felt the lump in her throat that appeared every time she had to knuckle down and do something against her will. It was only family that provoked this feeling. In fact, these days it was only her mother who could do this, once Áróra had told Ísafold that enough was enough, and they had ended all communication. Now it was only her mother who made her feel that she was being forced to do things that she didn’t want to do. ‘I’ll try and get hold of Björn or someone tomorrow, Mum.’

‘Couldn’t you try this evening?’ her mother said in a wheedling voice. ‘Just to see if everything’s all right?’

‘Tomorrow, Mum. I’ll check it out tomorrow.’

Áróra put the phone down without giving her mother an opportunity to protest. This was a little piece of her sister’s martyrdom she could do without right now. She was too tired to deal with her sister’s lies, announcing in that imposing voice of hers that everything was just fine. Absolutely, perfectly, completely fine. She would have fallen against a radiator and broken her jaw, which stopped her from speaking on the phone, or taken a tumble on the steps in the block of flats where she lived and broken a 5finger, so writing anything on Facebook was out of the question. Áróra was also too tired to have Björn sniping at her, telling her that Ísafold was his girlfriend, and Áróra shouldn’t concern herself with things that were none of her business.

She plucked a bottle of sparkling water from the fridge and took it with her to the living room, where she let herself drop onto the sofa, wrapped herself in a blanket and drank a quarter of the bottle. The programme had already begun, although that didn’t matter, as she had seen it several times before, but she found her mind was no longer at ease. Now she had to swat aside uncomfortable thoughts as they came at her, as if her mother’s phone call had opened the flood gates that for a while now she had struggled hard to keep shut. Now she couldn’t avoid feeling irritation at her mother, anger with Björn and a nagging fear for Ísafold.

THURSDAY

2

‘You don’t try and strike a bargain after a deal’s been done,’ Áróra told the car salesman who sat behind his broad desk, leaned back in his chair and made himself comfortable. He was nothing like the man Áróra had met a week before, when he had hunched over the desk, trembling hands fiddling with a row of model cars, practically choking with sobs as he begged her to help him. He said that it wouldn’t be long before he would be having to sleep at the showroom; that was if he didn’t find out where his wife – with whom he was in the middle of a turbulent divorce process – had stashed the money they had saved over the last twenty years of marriage. It was a very tidy amount. There was a chance that a small portion of it had come from the showroom’s overseas commissions, which hadn’t all been declared to the taxman. This was why he wasn’t keen to get the British authorities involved, but instead had come to Áróra.

She had tracked the cash down, and now, after his initial relief, it seemed that the car salesman had become puffed up with arrogance and wanted to go back on the agreement he had struck with Áróra that would have seen her get a ten percent cut of whatever she found for him.

He snapped a piece of nicotine gum from the blister pack on the table in front of him and popped it into his mouth. His hair had been freshly cut and the jeans he wore with a blazer were a little too tight to be comfortable. She guessed that this was an attempt to turn the clock back. No doubt he had dumped his wife, replacing the person with whom he had built up the company with a newer model. That would explain her bitter enmity.

‘That’s a ridiculously high percentage for something that took 7less than a week,’ he said, chewing his gum fast and hard, as people do when they’ve recently stopped smoking.

‘That week meant a trip to Switzerland, ten hours of online research and purchasing data, so that week entails significant costs and time on my part. I work fast and I get results,’ Áróra said, speaking slowly and clearly to be certain he would understand. ‘That’s the percentage we agreed on when I said I’d search for your money.’

‘That’s extortionate,’ the car salesman said, folding his arms across his middle. ‘I’m not paying that.’

Áróra sighed. This happened more frequently that anyone could imagine. First there would be despair over lost cash, so people agreed to a high percentage, but once the money had been found it seemed that they only then began to realise just how expensive her services were.

‘It’s ten percent of the overall value, or nothing.’

‘Five percent is the absolute limit for this kind of thing.’

‘Up to you,’ Áróra said and got to her feet. ‘Then you can find someone else to track down your money, and good luck with that because I’m as good at hiding cash as I am at finding it.’

The car salesman shot to his feet, cleared his throat and coughed. He appeared to have swallowed his gum.

‘What the hell do you mean? You’ve already put it into my account.’

There was a shadow of the sob she had heard in his voice a week previously.

‘I have a twenty-four-hour recall option on all my bank transfers,’ Áróra said, taking out her phone, tapping in the banking app code and cancelling the transaction. ‘Done,’ she said, and walked out of his office.

She dodged between the cars in the showroom, every one polished to a shine, and headed for the door. Through the glass partition of his office, she could see the man tapping at his phone in desperation, undoubtedly checking his bank account, with which he had been so delighted the previous evening.8

Áróra was halfway across the parking lot outside when she heard his voice behind her.

‘OK, OK, no problem,’ he called after her, panting after jogging through the showroom. ‘You’re right. Of course we’d agreed. My bad.’

Áróra stopped and turned.

‘I was doing you a favour by agreeing to pay the whole amount into your account so you could pay my commission through your car business. But now that I’m not able to trust you, I’ll make the transfer, but I’m taking my commission out first.’

She held her phone and there was a questioning look on her face. The car salesman nodded and raised his hands in agreement.

Áróra opened the banking app again while the salesman stood there fiddling with his own phone, no doubt wanting to be sure that the cash came through.

‘That’s it,’ Áróra said. ‘Now we’re all square.’ She turned off her phone, dropped it in her pocket and waited a moment, just to see the car salesman’s face when he saw the result. She didn’t have to wait long.

‘No!’ he yelped, his voice full of despair and pain. ‘We’re not all square. That’s only half. Less than half…’

‘That’s right,’ Áróra said. ‘And it was an educational experience to see just what you’re really like. I started to have my doubts about your tales of woe – how your wife had hauled you over the coals during the divorce, had taken the house, and all that stuff you were whining about last week. So I’ll return the half that’s rightfully your wife’s to her Swiss account.’

‘You can’t do this!’ he called, and Áróra turned on her heel and walked away.

‘If anything, she deserves more for having to put up with you for twenty years,’ she muttered as she got into her car.

She started the engine and drove slowly out of the parking lot, giving a cheerful wave to the car salesman, who stood as if he had been turned to stone. This was one of the real perks of her job: being able to dispense her own justice.

3

The sisters’ relationship had been sour right from the start. One of Áróra’s earliest memories was the pure loathing in her sister’s eyes as she picked up a shoe and flung it at her, hissing from between clenched teeth, ‘Lousy kid.’

‘Lousy kid’ was an expression Áróra had got used to hearing. Her mother called her ‘love’ or ‘darling’ and her father used quirky Icelandic terms of affection: ‘sweet morsel’ or ‘cuddle dumpling’. But Ísafold never referred to her as anything other than ‘the kid’, generally attached to a less than complimentary adjective. That six-year age difference hadn’t been good for them.

It all changed when they moved to England, to their mother’s home town of Newcastle, when Áróra was eight. Ísafold was fourteen and her raging teenage hormones manifested themselves in a faceful of livid red spots. She was struggling at school, where she was teased, and that was when she began to seek out her little sister’s company. After a day of schoolyard humiliation, it seemed to be a relief for her to play Barbie dolls with Áróra, who worshipped her in the illogical manner of younger siblings. Áróra still remembered how thankful she had been for the attention. She even turned down a couple of playdates with friends at school, preferring to spend the time with her big sister and the Barbies.

Thinking back, she couldn’t be sure if they had spoken Icelandic or English those first few years in the UK. More than likely they had used some mixture of both languages, as is normal when each parent has their own mother tongue, but it wasn’t long after their father died that they switched completely to English. There was something a little silly about speaking Icelandic when there was no clear need to.

In Newcastle they lived in a typical middle-class house, with bedrooms at the top of a steep flight of stairs, a living room and 10kitchen downstairs, and even a securely fenced garden at the back, where Áróra happily made mud pies all year round. She dug holes for ponds and replanted plants, and whenever her mother complained that she was destroying the garden, her father had always been there to take her side.

‘Leave her to it. After all, she’s half an Icelander.’

With hindsight, Áróra wasn’t sure if he meant that she should be allowed to do it because it was such a change for an Icelandic child to get to play in unfrozen ground all year round, or if it was because there was no point trying to tame her wild Icelandic nature, which had a different rhythm to its English counterpart. There was so much that she now wanted to have asked her father, but when she realised, it was too late.

4

Edinburgh Airport was always a nightmare to get to, so Áróra decided to leave the car at home and take a taxi. It wasn’t that far that she could be bothered with trains and buses to save the taxi fare, as her mother would not have hesitated to do, reminding Áróra how badly she managed her finances. Her response was usually that there wasn’t much point in having money if you didn’t use it to make life easier for yourself.

It was a long time since she had been to Iceland in summer, but she remembered how cool it could be and had packed a few warm clothes in a weekend bag. She’d booked a hotel in the centre of Reykjavík. Its name wasn’t familiar, so it had to be a new place. Her mother had suggested staying with some relatives she barely remembered, but she had managed to dissuade her from making arrangements on her behalf. It was an evening flight, but it didn’t matter what time of day or night it was – she would arrive in daylight. It was June, with its cold sun that never left the sky.

The sisters had each inherited a mixed bag of genes. By nature Áróra was the more English of the two, but with typical Icelandic looks – a fair complexion and a robust physique. Ísafold’s darker looks were more English, with her ivory skin and petite frame, but she had always been instinctively more Icelandic than her sister, as she had spent more of her formative years in Iceland and had been closer to their father.

‘One’s an elf and one’s a troll,’ their father had said when they were small, managing somehow to make both appear desirable options. Ísafold was delighted to be an elf child, taking ballet and later gymnastics classes, for which her natural agility was perfect. Áróra was quite happy to be the family troll, taking after her father, whose build brought him work as a doorman and as a competitor 12at Highland games, so physical strength was often a subject of discussion in their house.

Whether they were in Iceland or England, the sisters found themselves between two cultures, often unsure which way to jump. Generally Ísafold would incline to her father’s point of view, while Áróra would side with her mother, whenever comparisons were made between the different cuisines, customs or languages, as if it was a competition.

‘Iceland one, England nil,’ Ísafold had hissed when their mother had made her feelings plain about Icelandic food, that it was only fit for savages, to which their father retorted that the best thing about food in Britain was breakfast. It always irritated him when his wife hinted that Iceland somehow lagged behind.

It also bugged him that whenever he had a spur-of-the-moment idea for a project or a trip, it never failed to trigger his wife’s inner brakes, as she counted the costs and drawbacks. The girls’ mother liked to plan things, to be organised in advance, to enjoy the anticipation instead of acting on impulse, as their father and the rest of the Icelandic side of the family were inclined to do.

Right now, as Áróra thought back, sitting in the back of a taxi on its way through Edinburgh, she decided that her father would have liked her to have been more Icelandic, and felt the pangs of loss and helpless regret that always gripped her when she thought of him. In some way, she felt that she had betrayed Iceland, and therefore him as well.

She had allowed Iceland to fade out of her consciousness, in spite of all the summer holidays and Christmases spent there. After her father’s death she had spun all sorts of excuses to avoid going there, which had stretched the family ties so much, the invitations to christenings, weddings and family reunions that Icelanders were so fond of became steadily rarer. Ísafold, on the other hand, had revelled in all of that. She had taken every opportunity to go to Iceland, and even made excuses for needing to be there. She had taken her friends there for weekends to show them 13Reykjavík’s night life, and as soon as she had been old enough, she found herself a summer job there. It hadn’t been any kind of a surprise when she hooked herself an Icelandic guy. Somehow, that had been what was always going to happen.

Travelling light, with hand baggage only, Áróra was soon through check-in and the security checks, leaving her almost an hour to kill before boarding. She marched through the departure lounge to the gate, found a seat on a bench and took out her phone. She had already called both Ísafold’s mother-in-law and her brother-in-law, Björn’s brother Ebbi, leaving voice messages for both of them, plus she had sent text messages to Björn. None of them had picked up, there had been no messages and nobody had called her back.

5

It was three years since Björn had appeared on the scene. It was soon clear that he was different from all of Ísafold’s previous boyfriends, none of whom had lasted long – the most enduring of them lasting less than a year. It was as if there had been some quality she had been searching for, and had found in Björn.

Áróra had allowed Ísafold to drag her along to the late-winter gathering of expat Icelanders in London. She had agreed to go against her better judgement, as she avoided the traditional food and found Icelanders less than pleasant once they started to sing. But Ísafold had piled the pressure on her sister, desperate to go and without anyone to go with, until Áróra let herself be persuaded. All she had out of it was an evening’s regret, sitting alone at their table, watching Ísafold dancing with Björn.

Björn was a good-looking guy. He was tall and thick-set, and from beneath his rolled-up sleeves complex snake-patterned tattoos peered, twisting along his muscular arms and under his shirt. He was at the party with a couple who lived in London, and he bought them all round after round. Áróra was very drunk by the time she found a taxi to take her back to their hotel, while Ísafold disappeared with Björn.

After that Ísafold had been besotted: Björn this and Björn that – he was all she could talk about. Áróra was delighted for her. Ísafold was overjoyed and in love; it was good to see her so happy. It seemed that the Iceland Ísafold had always pined to be closer to had finally welcomed her. She moved into Björn’s flat on Engihjalli in Kópavogur after they had known each other for just a few weeks.

‘Now you’ll have to find yourself an Icelandic guy as well,’ Ísafold had laughed soon after moving to Iceland, and Áróra had jokingly asked if Björn had a hunky friend. It was genuinely a joke. She valued her freedom too much to be tied down. 15

On the approach to Keflavík Airport, as she looked down at the grey-green moss that even after hundreds of years hadn’t managed to cover the jagged lava completely, she couldn’t recall exactly when things had turned sour with Björn. It had been quite early on, but not right away – she had visited them in Iceland, slept on the sofa and watched as Ísafold had made valiant attempts to get to grips with the Icelandic Christmas baking tradition. Everything had been fine then. They had laughed together, and she had found Björn fun to be around.

Then things had turned bad. It had begun with a tearful Ísafold calling her in the middle of the night, saying that Björn had hit her. Áróra had gone straight to Iceland, collected her sister and taken her for an interview at the domestic-abuse shelter; for the first time.

6

Áróra usually found Icelandic men brash, and often downright rude compared to British guys, but this one was different. There was nothing flustered about him, unlike those Icelandic men who would approach women hesitatingly but were prepared to shower them with abuse if their interest wasn’t reciprocated. This one came across with self-assurance. She sized him up in a moment: he looked fit, slim and good-looking, although there was a youthful look to his face, as the bristles of his beard were pale and sparse. A pressed shirt was tucked neatly into his trousers, and his tie was knotted tightly even though it was evening. She liked a man who took care of his appearance.

‘The same again for me,’ he said to the barman, handing him his glass. ‘And for the lady.’

She smiled and extended a hand. ‘Áróra,’ she said, triggering a look of surprise on his face.

‘You’re from Iceland?’

‘Half Icelandic,’ she smiled. ‘Or more likely, half English. I haven’t spent much time here these last few years. But I can still manage the language all right.’

‘And a sexy accent,’ he said, moving a step closer. ‘I was sure you were a visitor, either one of the luxury tourists or else a foreigner on a business trip.’

This was her opportunity to disappear, to gently reject his interest in her. But she sat still.

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘And do you have a name?’

‘Hákon,’ he said, and they shook hands a second time. He didn’t let go right away, and she felt a clear spark of energy between them. She tried to identify the smell of his after-shave, and had to admit to herself that this was one she hadn’t encountered before. But it was a good one, fresh with a hint of spice. For a second the 17thought crossed her mind to invite him up to her room, to try him for size and see how he measured up, to find out if he could get the blood pumping in her veins, but she immediately dismissed the idea. He had to be married.

‘Are you married?’ she asked, dropping the question without thinking, and he shook his head.

‘Separated. Two and a half kids.’

Fuck. She couldn’t use that as an excuse. She hadn’t gone to the hotel bar to look for prey. It was just that the wretched daylight was keeping her awake. There were blackout curtains in the room, but beams of sunlight still squeezed through the cracks, and after tossing and turning for a while, she had decided that a glass of wine or three might help her cope with this infuriating endless brightness.

7

Different physiques mean different diets and exercise regimes. So elf girls and troll girls don’t get the same treatment.

He puts two slices of toast on Ísafold’s plate for breakfast and piles mine high with bacon. After breakfast Ísafold goes for a run, and I go with Dad to the gym to lift weights.

Mum has nothing to do with exercise, says she doesn’t get involved in that kind of rubbish.

One day Ísafold demands to do weights with us, and I laugh at her and tell her that she won’t even manage the beginners’ weights. But Dad scowls and takes the weights off her bar, fibbing to her that when I started, it was with a bar with no weights. I start to say something to put the record straight, but he says ‘shhh’, and takes me to one side.

‘Ísafold is your older sister, but you’re stronger so you’ll have to look after her, so don’t put her down,’ he says. ‘Physical strength is an indicator of inner strength, and you have much more of that than she does.’

Looking in the gym’s mirror, I compare the two of us, standing side by side. There are thirty kilos at each end of my bar and nothing on hers, and it’s as if I can see myself growing. All of a sudden I’m a head taller than Ísafold, my legs are solid and my arms muscular. At the same time, she seems to shrink, withering away, as if she might shrivel up, as if there’s nothing under her pale skin but bone and sinew that she hardly has the energy to keep together.

That evening Ísafold is in tears because she’s put on a kilo, while I’m delighted at the extra weight. Muscles are heavy. More muscle means greater strength.

FRIDAY

8

Grímur was startled by the chime of the doorbell of the flat upstairs. Their flat. He got out of bed and tiptoed cautiously to the window, as if he was concerned that whoever was at the door with their finger on the bell might hear him. Not that there was any chance of that. His window, which overlooked the entrance to the block, was high enough up that there was little likelihood his footsteps on the carpeted floor would carry through the insulated walls and double-glazed windows; unlike the noise from the flat upstairs, the noise that came from them.

He was taken by surprise when he looked outside: the woman standing there looked like Ísafold, just a larger, fairer version of her. It took him a moment to realise that this had to be Ísafold’s sister, who lived in Britain. He remembered her. From the time she collected her sister from his place. Out in the car park was a car she had left running, with a little red badge from the car-hire company on the windscreen. It was only to be expected. Sooner or later, this had to happen.

Grímur stood still and watched the woman. She rang the bell a second time and shuffled her feet on the steps. Then she peered upward at the building’s walls, and he stepped back in alarm from the window, not certain whether their eyes had met for a fraction of a second.

He badly needed the toilet, and although he was determined to wait by the window until she had given up and gone, he couldn’t hold it any longer, rushed to the bathroom and noisily emptied his bladder. He washed his hands and splashed his face with cold water to wake himself up properly, and as he looked out of the window again with the towel in his hands, he saw that 20stupid Arab talking to the woman. Him sticking his nose in was only to be expected. It was as if there was absolutely nothing that was out of bounds to the boy. He wished there was a pane he could open so that he could hear their conversation, but judging by the Arab’s body language, he was telling her that he hadn’t seen Ísafold. He shook his head and gestured with his hands in every direction, as he always did when he tried to make himself understood in that hopeless mixture of Icelandic and English, while the woman listened and nodded.

When the woman got into her hire car and drove away, Grímur was able to breathe more easily. He choked back the irritation that welled up inside him when he saw the Arab still out there with a broom in his hands, sweeping clean the pavement in front of the entrance. It was true that he couldn’t sit still. Olga said she had told him at least a hundred times to stay inside, not to draw attention to himself, but the lad wouldn’t be told. That was his problem. Olga had asked Grímur to keep an eye out for him in case he sneaked out, but Grímur had given up on that. He wasn’t going to babysit a grown man. The boy would just have to take what was coming to him, just like everyone else.

Grímur could sense the bristles sprouting after their night’s growth. He couldn’t bear to run a hand over his face to find out just how bad it was. The hair would be growing on his head and his feet, not to mention his chest. And his balls. And then there were those lousy eyebrows.

He hurried to the bathroom and let the water run in the shower. He took a new pack of disposable razors from the cupboard under the sink and extracted four. Normally four was enough. He stripped and stepped into the shower. The water and the heat gradually softened the stubble, making shaving smoother and closer, keeping the growth back until the evening. He squirted a palmful of thick, white foam and rubbed it into his head. He always started with his scalp, then his face – eyebrows first, then beard. Then he would take a new razor and work his way down 21his body, finishing at his feet. After that he would soap himself all over and go over his body a second time with a fresh razor, to be completely certain that not one single disgusting, bacteria-carrying hair remained.

Sitting at the kitchen table, Grímur tried to calm his nerves, which had left his body as tight as a bowstring. The shower and the shave hadn’t been enough to calm him down. In his thoughts, the woman, Ísafold’s sister, continued to knock with her knuckles so loudly it was as if she were really at the door. It was only to be expected. It went without saying that sooner or later someone would come looking for Ísafold.

9

There were two people ahead of her in the queue for the information desk on the ground floor of the National Hospital in Fossvogur. Áróra took her place behind the second woman and waited her turn. She had been here twice before, on both occasions with Ísafold. The building’s lobby was a busy place, with people coming and going: doctors and nurses, patients in white, sidling out for a smoke, pushing ahead of them stands on wheels with plastic drip bags, as well as people in normal clothes, visiting or collecting elderly relatives, who sat primly in wheelchairs, or stood and shivered behind their walking frames.

The woman in front of her finished asking her questions, and Áróra prepared to step forward, when a young man in a green raincoat stepped in front of her, leaned against the reception desk and said something to the man behind the glass. Anywhere else in the world she would have had a few harsh words for him, but it wasn’t worth wasting her energy when faced with this typical Icelandic approach. Men pushed their way to the front of queues and women never gave way in traffic. It was as if joining a queue or giving someone else a chance was an alien concept.

Áróra glared at the man in the green coat as he finished his business and leaned in to the glass, giving the receptionist a smile as she did so.

‘I’m here to visit my sister, but I don’t know which ward she said she’s on,’ Áróra said. ‘Could you check for me?’

‘Sure,’ the man replied, and Áróra gave him Ísafold’s name, which he tapped into his computer. He peered at the screen. ‘I can’t see her anywhere,’ he said, and shrugged.

‘Really?’ Áróra said, feigning surprise. ‘Could you check again?’

He shook his head.

‘There’s nobody called Ísafold here.’ 23

‘Could she be down at Hringbraut?’

‘No,’ the man said. ‘There’s just one registry for the whole hospital, it doesn’t matter which building someone’s in.’

‘That’s weird,’ Áróra said. ‘Could she have been discharged sometime today or later yesterday? Could you check back a few days?’

The man tapped something in, squinted at the screen in front of him and shook his head again.

‘No,’ he said. ‘I don’t have anyone called Ísafold on record. You’ll have to get in touch with her yourself to make sure.’

If only it were that simple, Áróra thought, but thanked the man and went back into the cool summer’s day outside. At least she could be sure of one thing: Ísafold wasn’t in hospital.

10

‘What are you doing here?’

It was more or less the response she had expected from Björn when she turned up at the phone shop, where he worked some kind of part-time job that wasn’t important enough for him to be reachable on the phone. There wasn’t a great deal of warmth between her and Björn. The plan was to get this over with as quickly as possible, find out where she could get hold of Ísafold and take this information to their mother, whether it was a new phone number, a new workplace or a new fractured jaw that was the reason they hadn’t heard from her. Áróra was looking forward to getting this done, so she could go back to the hotel, dress herself up and go for a meal with the guy she had met in the bar the night before, and maybe spend a night with him before catching the midday flight home.

‘It’s a long story,’ she said. ‘Mum asked me to come. She’s going crazy because she can’t reach Ísafold. So I’m after her new phone number or anything that’ll put Mum’s mind at rest. Nobody answers the doorbell at your place so I suppose she’s at work. Is she still at that boutique in the Kringlan shopping centre?’

‘No, she left there a while ago.’

Björn took her elbow and steered her out through the doors and into the street. The sun was high in the sky and it was close to midday, but the contrast between bright sunshine and cool air still took Áróra by surprise every time she stepped outside. She preferred the milder climate in Britain. She could live with Scotland’s hard winters, as long as there were some warm days in summer. But the chill of the Icelandic summer was somehow a symbol of hopelessness.

‘Where’s she working now?’

‘How should I know?’ Björn asked, taking out an e-cigarette, 25puffing on it and exhaling a cloud of smoke with a strong strawberry aroma.

‘You live together, so you must know where she works,’ Áróra replied, trying to hide her impatience – with little success, judging by Björn’s expression.

‘We don’t live together any more,’ he said, dropping the vape into his pocket. ‘Ísafold walked out. I reckon she must have gone back to England.’

‘What?’ Áróra’s jaw dropped and she stared.

This wasn’t what she had expected. Ísafold was besotted with Björn. In her eyes he was the best, the greatest, the most wonderful, and as far as she was concerned, he couldn’t say or do anything that fell short of fantastic. That was apart from the hour or so after he had hit her. That was when she wept and wanted to leave. But the feeling rarely lasted longer than the time it took to patch her up. That was the way it had been each of the three times Áróra had hurried to Iceland when Ísafold had called her in tears.

‘Yeah,’ Björn said, and the familiar look of contempt that she loathed so much appeared on his face. ‘And if you were a decent sister to her, you’d have known that.’

He spun on his heel and went back into the phone shop. Áróra stood and stared at a bright-yellow dandelion that had pushed its way up through a crack in the pavement, shivering in the fresh breeze. Something serious must have happened for Ísafold to have decided to go back to England. She had never felt comfortable there, and Iceland had been her home for the last few years. Through most of her adult life she had made repeated attempts to settle in Iceland, taking a job in a fish plant that came with housing, and even spending a year running a farm. Most of these ventures had ended with her returning to Newcastle and immediately starting to organise the next trip to Iceland. Her repeated attempts to put down roots on this cold island had been unsuccessful, as if the country just spat her out again – until she met Björn.26

Regardless of whether Ísafold was in Britain or Iceland, it wasn’t like her to ignore their mother. There had to be something she didn’t dare tell her. Maybe she wasn’t sure how to break the news that she and Björn had parted. Perhaps she simply didn’t want to hear her mother say ‘told you so’. Or it could be that Ísafold had something else to hide. Björn might have left her so bruised and battered, she didn’t want anyone to see her, knowing that their mother would ask Áróra to go to Iceland and help her out. On top of that, Ísafold knew that Áróra’s patience was at an end.

But, as Björn said, Áróra would have known that if they had been closer; if she had been a decent sister.