Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: An Áróra Investigation

- Sprache: Englisch

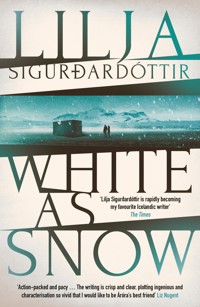

Daníel and Áróra hunt a brutal killer when a shipping container with the bodies of five women is found outside Reykjavik, as Áróra continues the search for her missing sister. Book three in the addictive, chilling An Áróra Investigation series. `Lilja Sigurðardóttir is good at describing the dark and cold of her native Iceland — and making you laugh … telling a terrific tale with twist after twist´ The Times BOOK OF THE MONTH `Another action-packed and pacy thriller … The writing is crisp and clear, plotting ingenious and characterisation so vivid´ Liz Nugent `Icelandic crime queen Lilja Sigurðardóttir goes from strength to strength, as is proved by White as Snow … protagonists tackling sub-zero temperatures and baffling crimes´ Financial Times –––– On a snowy winter morning, an abandoned shipping container is discovered near Reykjavík. Inside are the bodies of five young women – one of them barely alive. As Icelandic Police detective Daníel struggles to investigate the most brutal crime of his career, Áróra looks into the background of a suspicious man, who turns out to be engaged to Daníel's former wife, and the connections don't stop there… Daníel and Áróra's cases pit them both against ruthless criminals with horrifying agendas, while Áróra persists with her search for her missing sister, Ísafold, whose devastating disappearance continues to haunt her. As the temperature drops and the 24-hour darkness and freezing snow hamper their efforts, their investigations become increasingly dangerous … for everyone. Atmospheric, twisty and breathtakingly tense, White as Snow is the third instalment in the riveting, award-winning An Áróra Investigation series, as crimes committed far beyond Iceland's shores come home… Shortlisted for The Blood Drop – Icelandic Crime Novel of the Year, 2022 –––- Praise for the An Áróra Investigation series: `Icelandic crime-writing at its finest´ Shari Lapena `Lilja Sigurdardottir is rapidly becoming my favourite Icelandic writer´ The Times `Chilly and chilling … another tense and thrilling read!´ Tariq Ashkanani `The Icelandic scenery and weather are beautifully evoked…´ Daily Mail `A stand-out voice in Iceland Noir´ James Oswald `Sure to please Scandi-noir fans´ Publishers Weekly `So atmospheric´ Crime Monthly `Another bleak, unpredictable classic´ Metro `Tough, uncompromising and unsettling´ Val McDermid `Tense and pacey´ Guardian `Deftly plotted´ Financial Times `Breathtakingly original´ New York Journal of Books `Taut, gritty and thoroughly absorbing´ Booklist `A stunning addition to the icy-cold crime genre´ Foreword Reviews `A thrilling ride, super-addictive, fast-paced and atmospheric´ From Belgium with Booklove `Another emotional, pacy, tension-filled and highly topical investigation´ Jen Med's Book Reviews

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 369

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

On a snowy winter morning, an abandoned shipping container is discovered near Reykjavík. Inside are the bodies of five young women – one of them barely alive.

As Icelandic Police detective Daníel struggles to investigate the most brutal crime of his career, Áróra looks into the background of a suspicious man, who turns out to be engaged to Daníel’s former wife, and the connections don’t stop there…

Daníel and Áróra’s cases pit them both against ruthless criminals with horrifying agendas, while Áróra persists with her search for her missing sister, Ísafold, whose devastating disappearance continues to haunt her.

As the temperature drops and the 24-hour darkness and freezing snow hamper their efforts, their investigations become increasingly dangerous … for everyone.

Atmospheric, twisty and breathtakingly tense, White as Snow is the third instalment in the riveting, award-winning An Áróra Investigation series, as crimes committed far beyond Iceland’s shores come home…

WHITE AS SNOW

Lilja Sigurðardóttir

Translated by Quentin Bates

CONTENTS

PRONUNCIATION GUIDE

Icelandic has a couple of letters that don’t exist in other European languages and which are not always easy to replicate. The letter ð is generally replaced with a d in English, but we have decided to use the Icelandic letter to remain closer to the original names. Its sound is closest to the hard th in English, as found in thus and bathe.

The letter r is generally rolled hard with the tongue against the roof of the mouth. In pronouncing Icelandic personal and place names, the emphasis is placed on the first syllable.

Aktu-Taktu – Aktou-Taktou

Áróra – Ow-row-ra

Auðbrekka – Oyth-brekka

Baldvin – Bal-dvin

Elín – El-yn

Elliðavatn – Etli-tha-vatn

Garðabær – Gar-that-byre

Gylfi – Gil-fee

Gufunes – Gou-fou-ness

Gurrí – Gou-ree

Hólmsheiði – Holms-haythi

Ísafold – Ysa-fold

Jahérnahér – Ya-her-tna-hyer

Jóna – Yoe-wna

Keflavík – Kep-la-viek

Kópavogur – Koe-pa-voe-goor

Kristján – Krist-tyown

Lárentínus – Low-ren-tien-us

Leirvogstunga – Leyr-vogs-tou-nga

Mosfellsbær – Mos-fels-byre

Oddsteinn – Odd-stay-tn

Rauðhólar – Royth-hoe-lar

Sæbraut –Sey-broyt

Skeifan – Skay-fan

Smiðja –Smith-ya

Valur – Va-lour

Cold. It menaces her, forcing itself on her from every direction, searching for any way to get to her, slipping inside clothes, gnawing at flesh. It catches hold of extremities, fingers, hands, feet, legs as far as the knee. She fights back, shifting her legs. She gets to her feet and jumps, kicks into the darkness until she’s too weak to stay on her feet. That’s when she huddles into a ball and rubs her hands together, pushing them between her legs or into her armpits, and shivers. When she stops shivering is when she feels the numbness in her feet. It’s like they are gone, that they no longer belong to her. She can still move her feet, but has no feeling in them.

But cold is a liar. The numbness fades and the piercing pain that comes from inside, all the way from the bone, makes her again aware of her feet. She weeps, sees double so that the glimmer of light that comes through the grille appears multiplied and for a moment it’s as if she’s in her own bed at home, waking up to see the sunrise, and before long she’ll hear the cock crow and get up, go to the doorway and warm herself in the morning sun, listen to the news on the radio and drink coffee spiced with cardamom.

That’s how deceptive cold can be. It pretends to be warmth. It pretends that it’s warming her all the way through, and it’s such a joy to be warm that she loosens her clothing at the throat. But she’s too weak to undress. Clara lies half across her and she’s too heavy to be moved. So she just lies there and delights in finally being warm again, allowing herself to rest, to relax, to forget the nightmare of the last few days.

When she comes to her senses, the cold is everywhere. The deception is no more and she’s back in this wretched reality of a steel container that’s shaking. It rocks and rattles and shivers so that Clara is shaken off her, rolling to the floor where Marsela lies.

In the air there’s no sign of the newly risen sun or aroma of hot coffee, but just the merciless stench of fear and cold steel. With a struggle, she opens her eyes, but shuts them again as the white light flooding the container stings them.

TUESDAY

1

There was complete darkness in the room when Elín awoke. From the window, open just a crack behind the heavy curtain, she could hear a murmur, as if the wind played over the gap, producing a constant, monotonous whine that occasionally rose to a whistle. But it wasn’t the whine of the wind that had woken her, but Sergei’s voice from somewhere in the flat. He was on the phone, and she could tell from his tone of voice that he was speaking to the woman – the one who could call at any time of the day or night and who he said was his mother in Russia. That might be true, but there was still something odd about it – the way he left the room whenever she called and shut himself away. Why did he need to be in another room to speak to his mother? And anyway, Elín didn’t speak Russian, so he could be talking right in front of her, and she’d have no idea what it was about.

Elín stretched out a hand, felt on the bedside table for her phone, and was dazzled for a moment when the screen lit up bright blue, and she had to squint to see the time. It was getting on for six-thirty, so she might as well get up rather than try to go back to sleep. She was used to being up early and going down to her workshop, and had often been at work for two hours by the time Sergei knocked to let her know that he was awake and had made tea. It always took him a while to brew tea, as he followed a strict set of steps, adamant that it had to be done in a particular way. He started by making tea as dark as ink in a pot, then let it stand for a good while before decanting it into a small flask. Then he filled a large flask with hot water and sliced a lemon, putting the slices in their cups. By the time she came up, he was usually pouring the tea from the little flask into the cups – half a cup for him and just enough in hers to cover the bottom because she didn’t like it too strong – and then he filled the cups with water from the large flask. This was what he called ‘caravan tea’, and he was clearly convinced it was worth the trouble he took over it. She could just as well have dunked a tea bag in hot water and not noticed the difference.

Elín sat up, feeling with her toes for her thick woollen socks and pulling on her clothes in the darkness. She hadn’t exactly intended to eavesdrop on Sergei’s conversation, but found herself, almost without realising it, in the corridor, her ear to the bathroom door, listening to his strangely gentle tone. He had taught her a few Russian words, so she could pronounce them and understood whenever he said them to her, but when he spoke at his usual speed with other Russians, she couldn’t even tell one word from the next. His speech was just a string of strange syllables that all sounded much the same to her.

Tsya-tsya-sne-sne-minya-privnya-sne-sne.

It wasn’t the words that made her so heartsick, but his tone of voice, the gentleness of it. It was the tenderness that had captivated her because it was so diametrically at odds with his usual manner. Sergei was a big man, and looked to have some rough edges, although he was a good-looking guy, normally dressed in sports gear, with a gold chain dangling from his thick neck onto his chest, which he shaved in the shower at the same time as his head. When Elín suggested he wear a smarter shirt and a pair of jeans, he just laughed and told her that was the age difference talking. That Elín didn’t know anything about current street fashion and that he wouldn’t be putting on a shirt and tie, even though he was approaching thirty. When he reminded her, like this, of the almost twenty-year age difference between them, he left her with the lingering feeling that it was foolish for a woman of almost fifty to be so smitten.

This was the feeling that overwhelmed her now as she stood by the bathroom door and listened to him speak. Tsya-tsya-sne-sne. She felt, deep in her chest, that a hole had opened up in her heart, and the hot blood began to flood her belly, which stung with pain as she made out a familiar word. Baby, he had said into the phone. Come on, baby, as so often he said to her. When he needed to cajole her, get her to do something, take her out dancing, lend him money, get her between the sheets. Elín leaned against the door frame and hardly dared draw breath for fear of missing some word that she might know, some kind of clue. Who was he speaking to in this tone of voice? Wasn’t this the tender tone he kept for her alone?

Come on, baby. Come on, Sofia. Sne-sne. Tsya-tsya-sne.

2

The rust-red earth of the pseudocraters seemed brighter now that the ground was mostly covered in a thin layer of snow, which also seemed to have settled on the northern-facing slopes, as well as on the fence posts and the container itself, which was out of sight of the road. Daníel had parked at the side of the main road so as to not disturb any potential tyre tracks on the rarely used Heiðmörk road or on the track leading into the reddish gravel that gave the hills of the Rauðhólar district their name. Helena was on her way with the forensics team, and they too would leave their vehicles by the road – not sure yet whether it was safe to drive up here without comprising the evidence – and walk the rest of the way to the container, carrying any equipment they needed.

The snow had settled on the city during the night, melting almost immediately in the low-lying districts; but up here, according to the car’s temperature gauge, it was a couple of degrees colder. It was starting to get light as Daníel walked up the track, although it would be a little while before the pale March sun raised itself into the sky. He wasn’t exactly cold, but he zipped his coat up to the neck, as he felt a kind of a chill inside him. This had to be simple apprehension about what was to come. The message from the emergency call centre hadn’t sounded good. In fact, it had sounded horrific.

A jogger with a dog had come across the container first. The man made a habit of jogging here before eight every morning and had called the city’s environmental department, demanding to know what a twenty-foot shipping container was doing out here in this protected natural paradise.

The guy from the city council who’d turned up to take a look had opened the container and promptly vomited over his orange overalls. The two police officers who had been next on the scene had struggled to describe the sight that met their eyes. ‘A stack of corpses,’ they had said. A stack.

The officers stood some distance away from the container, one with his hands in his pockets, stiffly shuffling his feet. The other jogged on the spot, beating his shoulders with gloved hands to keep himself warm. Daníel thought he knew one of them but wasn’t sure. They had to be from the Dalvegur station. He fished out his ID, which hung from a lanyard around his neck, and held it up.

‘Daníel Hansson from CID,’ he said, and the two uniformed officers nodded at the same moment, neither of them bothering to glance at his card. Both of them had stiff, shocked expressions on their faces, and it seemed to Daníel that they were holding back tears.

‘We let the city council guy go home. He was ill at the sight of it.’

‘You took his details?’ Daníel said as he pulled latex gloves from his pocket.

‘I did,’ one of the officers said. ‘And I took a short statement from him covering why he came up here and opened the container, and what he saw inside.’

He held up a notebook, and Daníel nodded.

‘That’s good. You can write it up when you get back to the station and send it to me. What about the jogger who found the container?’

‘It seems the city council’s switchboard forgot to note down his name, but I guess CID can trace the number?’

Daníel gave a quick smile. Officers in uniform sometimes had strange ideas about CID’s priorities in the initial stages of an investigation.

‘We won’t worry about that right away.’ He pulled on one glove and looked at the two officers in turn. ‘What are we looking at, exactly, inside the container?’

‘I counted,’ the other officer said, the one who had been jogging on the spot. ‘There are five of them.’

‘All women?’ Daníel asked.

‘I think so.’

‘You think so?’ Daníel asked with a searching look.

‘Yeah. Well. It’s dark in there and, well … I don’t know. The city council guy threw up over the scene and I had to get him out of the way, and Jonni here went to call in for assistance and … well. I pretty much got out as quick as I could, and reckoned you’d check it out properly when you got here.’

Daníel had the second glove on.

‘Did you check all five for signs of life?’

‘Signs of life?’

‘Yes. Pulse, breathing.’

The officer stared at him in disbelief.

‘It’s not like that,’ he said. ‘You’ll see when you look inside. The smell, man. There’s a terrible stink. Just like at the apartment where that old guy was found after a month…’

‘Understood,’ Daníel said. ‘All the same, it’s a rule to always check for signs of life.’

He set off towards the container and slipped off one glove as he walked. He took a jar of tiger balm from his pocket and applied a generous amount under his nose. This wasn’t something he often needed to do, but having encountered the smell of someone long dead, he knew the instinctive reaction would be to retch, and going by the initial information, he would need to be in control.

If it was correct that there were the corpses of five women in the container, then the crime scene and the structure of the investigation would be an organisational nightmare. Daníel felt a weariness settle on his mind at the thought of it, but this vanished as he approached the open door of the container. There wasn’t so much a stench of death in the container. It was a smell of pure desperation. The sensation that sometimes came over him at a crime scene began – it was like a spark of light at the back of his mind, moving to his forehead until it interrupted his vision for a moment, then becoming a whirlwind that spun through his head while a voice hissed in his ear that death had come calling here, ice cold and ruthless.

3

The kettle was boiling when Elín heard the bathroom door open. Sergei came out. He wore boxers and a T-shirt and smelled as if he had just shaved. Had he locked himself away because he was shaving?

‘I’ll make caravan tea,’ he said, laying an arm across her shoulders and quickly squeezing her against him as he planted a kiss on her neck. Elín felt a wave of delight, but also a touch of disappointment as bristles rasped against her skin. He wasn’t freshly shaved, so that wasn’t the reason he had locked himself away in the bathroom.

‘Who called?’ she asked, looking at him enquiringly, trying to assess whether or not he was telling the truth.

‘It was my mother,’ he said, quickly glancing up before going back to the tea procedure.

It seemed to Elín that he was telling the truth. But that was her all over. She always believed him – mainly because she wanted to believe him. She longed to believe in the rightness of old-fashioned romance, and that everything really could turn out for the best; that Sergei was as in love with her as she was with him, that they could have a bright future together filled with joy and happiness. She wanted to believe that the woman he hid away to speak to really was his mother.

He carried the tea cups to the little table under the kitchen window and sat down. Elín took a seat facing him.

‘What did your mother have to say?’ she asked.

‘The same as usual,’ he said. ‘She’s short of money. Things are tough in Russia. Especially for old people, for old ladies. She has no savings. But I told her she would have to make it through to next week. There’s a guy I’ve been doing a lot of work for who owes me quite a bit, so she’ll have to wait until he’s paid me.’ Sergei paused, and Elín knew what was coming. ‘Unless you … No, nothing. Forget it.’

Sergei gazed at her with what she thought of as puppy-dog eyes. He looked awkward, and his brown eyes seemed to become wider.

‘Yeah,’ Elín muttered. ‘I can give you something to tide her over.’

She reached for the handbag that lay on the kitchen windowsill.

‘No, no. Forget it,’ Sergei repeated, but she knew he didn’t mean it. He feigned reluctance to accept money because she had already loaned him some, but she was aware that he had few other options. He had no regular income – only what he picked up working the odd shift as a doorman at various clubs, or doing removals or whatever else came up that called for strength and was paid cash in hand. And anyway there was nothing wrong with lending him money. She had often done it and he had repaid her quite a few times. Not that she kept a precise tally. There wasn’t much point in that, considering they lived together.

She opened her wallet, counted out a few five-thousand-krónur notes and handed them to him. A quick smile appeared on his face, he nodded and took the cash.

‘Thanks, Elín,’ he said. ‘I’ll pay you back as soon as I get some money.’

‘Don’t worry about it,’ she said, and sipped the hot tea. For a moment she basked in the sense of bliss that came from being in Sergei’s proximity. The tea warmed her inside, and the smell of his aftershave was good. She could spend an age sitting like this, admiring his musclebound arms and taking deep breaths of his aroma. She could revel in the domestic routines they had so easily slipped into, sink herself into the love that she felt enveloped them like a cloud whenever they were together.

But then the disquiet sought her out once more, along with the questions that multiplied every time this woman phoned. Why did Sergei hide away like this if it was his mother calling? Before Elín knew what was happening, she once again found herself deep in the cold loneliness of jealousy.

‘What’s your mother’s name?’ she asked, surprised at herself for never having asked this before. Sergei looked back at her and narrowed his eyes, the puppy-dog expression gone now.

‘Why do you ask?’ he said, no warmth in his voice.

‘Just because,’ Elín replied, trying to sound unconcerned. ‘I was just wondering what her name is.’

‘Her name is Galina,’ Sergei said. There was a sharp look on his face, as if he were waiting for an argument. As if he was waiting for her to ask more questions, to accuse him of something; and he was right.

‘Oh? I thought her name was Sofia,’ Elín said, wishing as she spoke that she could have bitten her tongue, because Sergei rose to his feet so fast that he sent the kitchen chair flying to the floor and then kicked it halfway into the living room.

‘Sofia?’ he snapped. ‘Why do you say that?’

‘I heard you say something on the phone that sounded like Sofia,’ she said humbly, longing now to throw herself at his feet and beg his forgiveness; to make it all good again, to beg him to sit down, make more tea and look at her once more with those puppy-dog eyes and not this hard, cold glare.

‘Are you listening to my calls…? Are you spying when I’m on the phone, thinking you hear the names of other women? Is your Russian so good that you can hear me say other women’s names? That’s fantastic!’ He picked up the notes from the table and flung them at her. ‘Keep your money. I’ll find some other way to support my mother. I can’t live with this suspicion.’

He snatched his coat from its hook and stormed out. Elín started as he slammed the door behind him.

4

Helena slowed down and brought the car to a halt by the gravel track leading up to Rauðhólar, giving way to the ambulance, which was turning onto the main road. She drove along the track and parked on the verge at the top, and as she got out of the car, she could hear the wail of the ambulance’s siren down on Suðurlandsvegur. That would get them through the morning rush hour, which was now at its peak and which would stay busy until after nine. The number of cars that had collected by the side of the main road was a concern – a patrol car made its way through the middle of them, its blue lights flashing. This would attract the attention of the hundreds of people heading either into the city or out of it, up to the heath, and sooner or later someone would tip off the media. It was as well that the container itself was out of sight of the road, and that the forensic team had decided to park further along, so their white van wasn’t easily visible from the road and was still some way from the container.

The red gravel crunched under Helena’s feet, and she recalled when it had been a common sight on pavements and drives throughout the city. There was something enchanting about its colour, and back then people had no idea of the geological importance of the area it came from, so removing a trailer of dirt from this or that mound wasn’t seen as anything to be concerned about. They knew better now, and it had slipped out of use.

She took care to walk on the verge, although there was no need to, as the ambulance had most likely eradicated any tyre marks – if there had been any – and as she approached the container she saw the tangle of footprints in the thin layer of snow that covered the red gravel. There was something Christmassy in the juxtaposition of these colours and the green of the moss that peeked here and there from beneath the snow, now that the morning sun had made a late appearance and was picking out every detail.

This pleasant feeling quickly vanished when Helena spotted Daníel on his knees in the heather, shivering. She sent an enquiring glance to the uniformed officer who stood not far from the container, but he stared back with dazed eyes. She knew that look. The man’s mind was elsewhere; more than likely he was thinking about something mundane and ordinary, something that he meant to fix in the garage at home or the TV series he was currently watching. This was the soul’s defence mechanism at work, protecting him against the ugly parts of life.

She clambered over the tussocks and into the heather to crouch at Daníel’s side. His breath came in heavy gasps and he growled from between clenched teeth, as if his powerful jaw and teeth struggled to hold back a colossal flood of sorrow.

‘There was one still alive,’ he gasped. ‘She was still alive in the middle of the pile. The bodies of the others must have been just enough to keep her warm.’

Helena placed a hand on his back and gave him a couple of firm strokes.

‘I heard at the station,’ she said, ‘that she’s regained consciousness.’

Daníel snorted, apparently dismissive, but Helena knew him well enough to know the sound indicated surprise or astonishment.

‘I don’t know if I’d call it conscious, exactly,’ he said. ‘I could hardly believe she had a pulse, so I pressed harder to make sure and she jumped to her feet and rushed out onto the moor, howling in terror.’ He took a couple of deep breaths. ‘I tried to tell her again and again that I’m from the police. I’ve no idea if she understood me, but in the end she let me wrap my coat around her. Maybe she was just too exhausted and cold to protest.’

‘Christ, Daníel,’ Helena said. ‘Unbelievable.’

Daníel lifted himself up, got to his feet, shivered, and stared in fury at the container. Helena felt a jolt of surprise when he let out a heartfelt howl of rage; but it failed to carry far – it was swallowed up by the mutter of traffic on Suðurlandsvegur and muffled by Rauðhólar’s snow-speckled moss.

‘Never seen anything so totally fucking revolting.’

5

Elín was still trembling inside as she went down to her workshop, wondering whether to forget work and just go back up to the flat and spend the day watching television. But today not even a crime series was going to be enough to capture her attention, let alone one of the soap operas she and Sergei usually watched. Every argument with Sergei left her feeling like this – with her nerves shredded; that, or dissatisfied. Dissatisfaction was hardly the word; distressed was better. The pattern had always been a sharp exchange, followed by Sergei storming out. Elín had found it so distressing the first time it happened, she hadn’t been able to get it out of her mind. She had even wondered if he had gone for good, abandoned her, so by the time he returned, she had cried all the tears she had to shed. Now that she’d seen him storm out and return more than once, she knew that this was his way of cooling off – calming himself down and regaining his composure. He’d return, placid and sensible. Normally he’d apologise and they would be friends again.

Even though she knew that he would come back and that they would quietly make up in peace and quiet, she still felt disturbed. There was a knot of tension deep inside her, she felt nauseous and every nerve in her body felt as taut as a violin string. She was sure that if she were to put a microphone to her skin, she would hear the sound of these overstretched nerves – a painful chorus of anxiety, almost clear enough to call Sergei home to comfort her. No, it would more likely be her role to comfort him, to ask his forgiveness and apologise for her jealousy. Now, down here among her paintings, she couldn’t imagine what she had been thinking, what kind of suspicion had taken root inside her.

Elín looked around the little studio she had installed in the garage on the ground floor of her terraced house and suddenly felt that the place was a mess. In truth, it was no more disordered than usual; it must be her state of mind that was making her think this way.

She was about to give up for the day on the painting she was working on, and had started preparing a new blank canvas when her phone rang. She snatched it up and rushed to answer, certain it was Sergei, but it turned out to be her father.

‘Well, sweetheart,’ he said cheerfully. ‘What’s new in the art world?’

This was his standard opening question whenever he called or visited. She never failed to reply in the same way, that there was precious little to report. It was true in a way: in terms of her work one day was much like the one before. She stretched canvases, put down a base wash, sketched outlines with a pencil and then began to paint – and she couldn’t talk about paintings while she worked on them. If she tried to explain what lay behind them or how they had developed, it was as if the flow had been interrupted and she would lose interest. Maybe this was something akin to writer’s block. She never spoke about a work until it was complete, which meant she rarely had much to tell her father. Throughout her career she had exhibited every second year, but recently, she’d begun to feel that she didn’t have a body of work strong enough for an exhibition, so the paintings had begun to stack up. She wondered if she was losing the self-confidence an artist needed to put on an exhibition. There was certainly some kind of internal obstacle preventing her from producing the right material. Occasionally she would sell a work straight from the studio, but that was rare these days. She lived mainly on the rent she earned from another apartment, which she had bought when her father had paid out her inheritance in advance. It provided her with a decent income as she had already paid off her mortgage on her own place.

‘I’m stretching a canvas,’ she told her father.

‘Well, love,’ he said, and she could imagine him in his wheelchair by the living-room window, looking out over the burger joint and the slipway across the street.

‘What ship is out of the water now?’ she asked, and heard as he sat up in his chair, relieved to have something to tell her.

‘Saltvík,’ he said, and she scrawled it at the bottom of the list of ship names she had been collecting on one of the studio walls. This had become a game for them over the years, ever since her father had bought a flat overlooking the slipway. She liked collecting the names and was sure that one day something linked to this would become a painting. That was where ideas came from – something insignificant, often a trivial detail. A routine or some habit would take root, and at some point would ignite the fuse of inspiration, like a spark in a powder keg.

‘Well,’ her father said, and Elín knew what was coming next: ‘Your Russian’s being good to you, is he?’ he asked.

She sighed.

‘Yes, Dad. Sergei’s fine.’

Her father never referred to Sergei by name, always as the Russian, and Elín could tell that he was not fond of this choice of hers, although he was unfailingly courteous whenever he met Sergei.

‘He hasn’t been talking about a wedding again?’

‘He has, actually,’ she said slowly. This wasn’t something she wanted to discuss with her father, especially now, in the middle of a disagreement with Sergei. ‘He needs a residence permit and a work permit, and getting married is the easiest way to fix that.’

She had already explained this to her father more than once, but he never seemed to take notice and every time it was as if this was something new.

‘Well, now.’ Her father hummed over the phone, and Elín hummed back, as if their conversation had suddenly run aground and neither of them quite knew how to get it afloat again.

Her father was the first to break the ice. ‘Remember what I said to you the other day about a pre-nup,’ he said. ‘Because you have assets, and he doesn’t. So you’ll have to have a pre-nuptial agreement if you get married. Which you know I think is complete madness.’

6

‘I’ve only been ready to quit once in my whole career,’ Daníel said to the commissioner, who drew up one of the red armchairs that were arranged in her office, and sat down facing him, so close that their knees almost touched. ‘That was an investigation into a house fire in which someone died and I … I’ve never been able to clear my mind of the image of that person’s body, or the smell. The smell was the worst part.’

‘Drink this,’ the commissioner said and passed him a cup she had filled with Coke. ‘The sugar will pick you up.’

Daníel took the cup, drank half the sweet pop and almost took comfort in the feeling that his taste buds were being wiped clean, even though all his other senses were still shackled to the woman who, only two hours ago, he had cradled in his arms and covered with his coat, and to whom he had muttered that he was from the police and was there to help her, faintly hoping that his words would make it through the terror in her eyes and her chilled-through body, and that if they did make it through, they would have some meaning for her.

‘I feel I’m ready to burst,’ he said. ‘I want to go down to the docks and yell at Customs that they need to check every single container that gets shipped to Iceland. They need to open every single one and…’ His words faded away as the memory of the contents of the container up at Rauðhólar appeared again in sharp relief before his eyes – the bodies of women wrapped in clothes and blankets that were nowhere near enough to cope with the cold of winter up here in the north.

‘That would be the ideal situation, but even if funding for the Customs service was ten times what it is now, doing that still wouldn’t be realistic,’ the commissioner said. ‘They only manage to check a tiny fraction of the containers that arrive here. That’s why our work is so important. We have to nail whoever was behind this horror.’

Daníel shook his head, not sure if it was the commissioner’s words he wanted to shake off, or the memory of the curly, foul-smelling hair on the head he had held tight, in the desperate hope the woman would sense some warmth from him, even a little humanity and goodwill.

‘The smell…’ he said, looking up to meet the commissioner’s eyes. ‘Her smell, and the look in her eyes … I can’t do this. I can’t work on this case.’

The commissioner sat a little straighter.

‘You are one of my most experienced officers,’ she said. ‘This is going to call for a large team, but I can ask the chief superintendent to keep you away from any major responsibilities – you had asked for time off to look after your children before this, anyway. We do need someone of your calibre on this, though. Someone who can read people. Someone with your deep understanding – your insight and sympathy.’

‘What you call insight is really working against me right now,’ Daníel said. ‘The whole world is somehow becoming too … too something for me. After all these years of all kinds of investigations, I’ve hit my limits. I can’t handle my job if it’s going to get any worse.’

The commissioner placed a hand on his arm and squeezed.

‘Daníel,’ she said, and tried to catch his eye. ‘It can’t get worse than this. This is as bad as it gets.’

7

Helena was startled when she entered the large room: it was packed with people, some of them on their feet, as there were not enough chairs for everyone. It was clear that everything was being thrown at this investigation: representatives of every branch of the force, support departments included, were present. She slipped between the bodies and found a perch on the end of a table from which she could look around the room. The atmosphere was subdued, people speaking in low voices, and from what she could make out from the whispers, they were mostly questions. Apart from her and Daníel, it seemed likely that few people knew what this was about.

She looked for him, but he was nowhere to be seen; however when the commissioner entered the room, accompanied by Gylfi, the chief superintendent responsible for CID, Daníel was with them. For a moment she wondered if the unhappy look on his face meant that he had been given responsibility for this investigation. She saw him searching the faces, then he caught her eye and gave her a quick wink – to her relief. This was the signal they kept for each other, an indication that things were fine, so she now felt sure that he wouldn’t have to shoulder the burden of this horrific case.

Helena thought of him this morning, kneeling in the peat, overcome with despair, and she was glad that he wouldn’t be under the yoke of this investigation. She had seen how people struggled with serious criminal cases and how personally they took it when the cases remained unsolved.

The commissioner cleared her throat and a silence fell across the room. Chief Superintendent Gylfi glanced at her, nodded, looked over the assembled throng, and nodded again before speaking. This was a habit of his that some people found endlessly irritating. Helena found it a rather amusing mannerism, and enjoyed seeing it made fun of so often at the station. Opinion was that the number of times he nodded his head before speaking was an indicator of how serious the case would turn out to be. This certainly applied now, as she reckoned that he had nodded his head no less than seven times before saying a word.

‘Just before eight this morning the emergency line had a call informing them that a twenty-foot shipping container had been found in the Rauðhólar park, south of Suðurlandsvegur, and in it were several bodies. Police officers established that in the container were five women, of whom one was alive and four were dead. The suspicion is that they died of hypothermia or from the effects of the poor conditions inside the container. It was clear that the women had been in it for some time. The nationality of the victims is unknown, although the indications are that they are of foreign origin. We are assuming that they were brought to Iceland in the container. The fact that these women were not simply doped and put on a plane, as we have seen happen before, indicates that they are from countries that do not have access to the Schengen agreement, or that they would require visas to enter Iceland.’

‘Are we talking about people trafficking?’ Kristján asked from where he stood in a corner.

Gylfi nodded gravely twice.

‘It’s a strong possibility, so it’s a scenario we will examine.’ He nodded again a couple of times, as if fumbling around for the thread he had lost when Kristján interrupted him. Then he continued: ‘The survivor is suffering from extreme hypothermia and is being treated at the National Hospital. She’s lost consciousness again. The doctors say that they will be able to tell in the next couple of hours if she’s likely to regain consciousness anytime soon.’

Gylfi gazed over the group in front of him, his head rising and falling as if he was registering the reactions of those present. Most seemed appalled.

‘This investigation has been given top priority, which is why you have all been called in to work on it,’ he said. ‘The commissioner and I have decided that it calls for a substantial response, which can be scaled back if necessary, rather than the opposite approach. From this moment this is the only case you are working on. I’d like you all to list your current active cases and send them to me. I’ll assign them to other teams.’

For the first time since Gylfi had starting speaking, a low murmur went around the room. People could get close to a case, even becoming emotionally attached, or, as the chief superintendent had been known to describe it, hanging on to it like a dog with a bone.

‘I will manage this investigation personally,’ he continued, ‘and will handle the media myself. I don’t need to emphasise to you the importance of maintaining discretion and sending any media questions in the right direction. There’s no doubt that news of the container will soon hit the front pages, but the fact that one of these women is alive is something we’ll keep to ourselves for as long as possible.’ Now almost everyone in the room was nodding in agreement. ‘The nature of this case means that there’s going to be all kinds of rumour and speculation, so we all need to take care not to add to the media madness.’

The chief superintendent fell silent and stepped aside, and the commissioner took his place.

‘I want to introduce our colleagues from the support departments,’ she said. ‘Most of you know each other already, but it’s as well to be clear about who does what. First is Jóna, who is the forensic pathologist.’ The commissioner gestured to an older woman with a bun of grey hair who was sitting to one side. ‘Her role, as usual, is to establish the cause of death, and in this instance there is the task of identifying the deceased. She will be supported by the national police commissioner’s International Division, so I’d like to introduce Ari Benz Liu, chief superintendent of the International Division.’