6,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

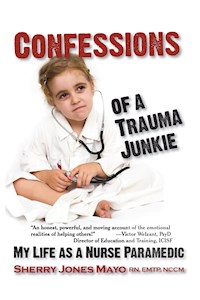

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: Reflections of America

- Sprache: Englisch

Ride in the back of the ambulance with Sherry Jones Mayo

Share the innermost feelings of emergency services workers as they encounter trauma, tragedy, redemption, and even a little humor. Sherry Jones Mayo has been an Emergency Medical Technician, Emergerncy Room Nurse, and an on-scene critical incident debriefer for Hurricane Katrina. Most people who have observed or experienced physical, mental or emotional crisis have single perspectives. This book allows readers to stand on both sides of the gurney; it details a progression from innocence to enlightened caregiver to burnout, glimpsing into each stage personally and professionally.

Emergency Service Professionals Praise Confessions of a Trauma Junkie

"A must read for those who choose to subject themselves to life at its best and at its worst. Sherry offers insight in the Emergency Response business that most people cannot imagine."

--Maj Gen Richard L. Bowling, former Commanding General, USAF Auxiliary (CAP)

"Sherry Mayo shares experiences and unique personal insights of first responders. Told with poetry, sensitivity and a touch of humor at times, all are real, providing views into realities EMTs, Nurses, and other first responders encounter. Recommended reading for anyone working with trauma, crises, critical incidents in any profession."

-- George W. Doherty, MS, LPC, President Rocky Mountain Region Disaster Mental Health Institute

"Sherry has captured the essence of working with people who have witnessed trauma. It made me cry, it made me laugh, it helped me to understand differently the work of our Emergency Services Personnel. I consider this a 'MUST READ' for all of us who wish to be helpful to those who work in these professions."

--Dennis Potter, LMSW, CAAC, FAAETS, ICISF Instructor

"Confessions of a Trauma Junkie is an honest, powerful, and moving account of the emotional realities of helping others! Sherry Mayo gives us a privileged look into the healing professions she knows firsthand. The importance of peer support is beautifully illustrated. This book will deepen the readers respect for those who serve."

--Victor Welzant, PsyD, Director of Education and Training The International Critical Incident Stress Foundation, Inc

From the Reflections of America Series

Medical : Allied Health Services - Emergency Medical Services

Biography & Autobiography : Medical - General

Psychology : Psychopathology - Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 394

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Ähnliche

Reflections of America Series

From Modern History Press

Confessions of a Trauma Junkie: My Life as a Nurse Paramedic

Copyright © 2009 by Sherry Jones Mayo. All Rights Reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mayo, Sherry Jones, 1955-

Confessions of a trauma junkie : my life as a nurse paramedic / by Sherry Jones Mayo.

p.; cm. -- (Reflections of America series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-932690-96-5 (trade paper : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-932690-96-4 (trade paper : alk. paper)

1. Mayo, Sherry Jones, 1955- 2. Nurses--Biography. 3. Emergency medical technicians--Biography. 4. Emergency nursing--Biography. I. Title. II. Series: Reflections of America series.

[DNLM: 1. Mayo, Sherry Jones, 1955- 2. Emergency Medical Technicians--Personal Narratives. 3. Nurses--Personal Narratives. 4. Emergency Medical Services--Personal Narratives. 5. Emergency Nursing--Personal Narratives. WZ 100 M47315 2009]

RT120.E4M345 2009

610.73092--dc22

2009017672

Distributed by Ingram Book Group

Published by Modern History Press,

www.ModernHistoryPress.com

An Imprint of Loving Healing Press

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI 48105

www.LHPress.com

Tollfree 888-761-6268

Fax 734-663-6681

Praise for Confessions of a Trauma Junkie

“A must read for those who choose to subject themselves to life at its best and at its worst. Sherry offers insight in the Emergency Response business that most people cannot imagine. This book details life through the eyes of a caring individual who is a devoted CISM practitioner and true professional, who continually accepts the crisis presented, employs best practices, focuses on the mission, and makes the trauma, pain and suffering a little easier to manage.”

—Maj Gen Richard L. Bowling,former Commanding General, USAF Auxiliary (CAP)

“We are not alone. Sherry Mayo shares experiences and unique personal insights of first responders. Told with poetry, sensitivity and a touch of humor at times, all are real, providing views into realities EMTs, Nurses, and other first responders encounter. Emotions shared bind this fraternity/sorority together in understanding, service and goals. Recommended reading for anyone working with trauma, crises, critical incidents in any profession. It’s heartening to know we share such common experiences and support from our peers.”

—George W. Doherty, MS, LPC, PresidentRocky Mountain Region Disaster Mental Health Institute

“In this book, Sherry has captured the essence of working with people who have witnessed trauma. It made me cry, it made me laugh, it helped me to understand differently the work of our Emergency Services Personnel. I consider this a ‘MUST READ’ for all of us who wish to be helpful to those who work in these professions.”

— Dennis Potter, LMSW, CAAC, FAAETS, ICISF Instructor

“Sherry has encapsulated the first responder human lifestyle and given it soul. Makes you appreciate those who serve others in what happens in the streets of America every day. Sherry gracefully exposes the dreaded ‘F’ word…Feelings… and will absolutely touch every reader in surprising ways.”

—Police Officer (Ret.) Pete Volkmann, MSW, EMTOssining, NY Police Department

“Confessions of a Trauma Junkie is an honest, powerful, and moving account of the emotional realities of helping others! Sherry Mayo gives us a privileged look into the healing professions she knows firsthand. Her deep experience is a source of knowledge and inspiration for all who wish to serve. The importance of peer support is beautifully illustrated. This book will deepen the readers respect for those who serve.”

—Victor Welzant, PsyDDirector of Education and TrainingThe International Critical Incident Stress Foundation, Inc

“Never before has anyone depicted, in such vivid detail, the real life experiences of a street medic. EMS is a profession that at times can be extremely rewarding and other times painfully tragic. Thank you for telling our story through your eyes!”

—Diane F. Fojt, CEOCorporate Crisis Management, Inc.Former Flight Paramedic

Table of Contents

Preface: The Healer Within

Part I – On the Road Again: Stories from Emergency Services Workers

Sweet Dreams, Angel

Cheap Date

Regan: Little Girl Lost

Gross is in the Eye of the Beholder

95% Boredom

Trauma Junkie in the Air

Jeff Washington

Part II – The Other Side of the Gurney: The Mortal Side of Emergency Service Personnel

And Puppy Dogs’ Tails

Daddy’s Little Girl

Final Directive

We’re Not All That Tough

Batnofly Croswellian

Shadows on the Wall

Rollover

Part III – ER Short Stuff: The Day to Day Life of Emergency Room Personnel

ER Triage: What’s in a Name?

ER Triage: How Can We Help You Today?

A Curtain is Not a Wall: Things overheard…

Nurse’s Notes

A Few of My Favorite Things

I’m NOT Letting You Go

Part IV After the Call…: When It Isn’t Really Over

Julia’s Story

Delayed Reaction

Katrina: After the Storm

What Did You Do At Work Today, Mommy?

About the Author

Glossary

Index

Preface: The Healer Within

If we accept the premise that each of us is a special creation placed on Earth to perform as well as our design would enable us, I believe there is an individual choice whether or not to act upon inherent capabilities and gifts. In this case and in this book, this reference points to the healer within. As such, I believe that all the “secrets” held since the beginnings of time are for each of us to explore. No special dispensation is necessary; we are given access to it all and the capability to understand and take action, we are granted permission to enter into a world of limitless possibility. We truly choose our own adventure.

Sometimes the search for (and development of) talents takes one on diverse paths of self-discovery. I hold in memory a crystal image of my own day of realization, etched with full-spectrum coloration, when the dark curtain of ignorance fell away and the door to where answers are found was flung open before me. That moment prompted exploration into the mind/body connection where psychology and medicine merge. I’m still wading in that pool, taking it all in and learning as I go along. While I learn, I laugh a lot because lunacy abounds and I cry sometimes because humanity suffers so much pain. In that place between lunacy and sorrow, I grab a home-made water pistol (30cc syringe with a 22-gauge plastic IV catheter), and take aim.

This book is a peek into the world of EMS and ER folks from those who do those jobs daily. It is comprised of essays and quotes—all true though sometimes compiled—from EMTs and RNs around the country (names and some details occasionally changed to protect the guilty). This is your opportunity to share in the pain and laughter (not just the patient’s, but our own) while we go through life trying to keep from succumbing to whatever evil presents itself. We fight the enemy (death) with everything we have and try to keep a sense of humor while doing it. There are many more stories to be told… this is just a handful of them written by a Paramedic RN who has worked rural, country and city EMS as well as an urban trauma center since 1989 and continues to play in the ER pond today. That said, please don’t take offense—some of the items shared are less than politically correct, but that is to be expected when stories are relayed between those who do this work. Walk a mile in our shoes and we’ll talk about what truly offends. Walk two miles and you’ll have stories of your own and a greater understanding of the sights, smells and experiences of those who expertly do what nobody should ever have to do.

How we have (in medicine) separated the mind from the body baffles me. We know that our cells have an innate intelligence and somehow group with other cells that hold a common desire to sustain growth and continue life; similar cells combine to develop tissues, related tissues become organs, systems form and the infinitely small parts together become a functional whole. Our bodies are composed of energy and information; there is intelligence in each of the cells as there is intelligence in the organism (human being), directing and guiding toward the collective good and development of the entity.

By the end of one year, 98% of the body’s atoms are exchanged for new ones, which is a built-in mechanism for change, renewal and regeneration. Unifying the body and mind toward positive and forward growth is sometimes a challenge when either stumbles over pebbles (or boulders) in their paths; balance is interrupted and intervention is necessary (from internal or external sources) to recover physical and mental homeostasis. What we don’t know is what happens in that moment between thoughts, the moment between desiring and directing a physical action and its ultimate implementation; even when we do discover some of the mysteries of the mind we continue to tread water in their interpretations. Despite intellect, education, desire and experience, how we communicate is a mystery, too, as any married couple will tell you.

Life is a journey of discovery; learning is a relatively permanent transformation in an organism resultant of experience or acquired information. Working in the world of medicine (and mental health) provides multitudes of opportunity for education and change. I am emphatically not the person I was before becoming involved with medicine in the streets and in the ER, nor could I have known where searching for answers to the pain I witnessed in others as well as myself would lead. A gateway has been opened and I’ve stepped across a threshold to a new plane of existence that in the past appeared only fleetingly in the back of my consciousness. I am not an independent creature who can trek through life loving selectively and denying my affiliation with humanity or the universe; we are joined with each other. I am a spiritual being encased in a physical body—over which I have tremendous influence despite my immature denial in years past—who maintains a conscious walk into self and cosmic awareness.

The quest for answers and direction in response to emotional pain also led me to Jeffrey T. Mitchell, Ph.D., C.T.S., George S, Everly, Jr., Ph.D., ABPP, Dennis Potter, LMSW, CAAC, FAAETS, and my dear friend and mentor, Victor Welzant, PsyD, all from the International Critical Incident Stress Foundation (ICISF), who have provided a program of interventions that I have utilized and seen successfully applied countless times to thousands of people. I thank these brilliant and caring gentlemen for their unwavering guidance as I continue to learn from them.

From my family, of course, I have learned the most. From my children I have come to know and appreciate (and hopefully apply) unconditional love; they have gone from being my students to showing me wonderment I could not have imagined and I continue to learn from them daily. “Topher,” my sweet and generous computer genius son (programming at age six) has always had a vision that others couldn’t see or understand; still, he patiently points toward those unseen things that are beyond common comprehension, good-naturedly teaching concepts from the complex to the simple, like an introduction to the Mandelbrot set or showing me how to build and maintain a fire. Sometimes the mother but certainly always the devoted daughter and comedian, Michele Denise (named after her Grandfather Michael Dennis) lovingly keeps me from embarrassing myself in public (sometimes), attempts to influence my wardrobe and shows me how not to grow up. Grandson Sean is the new Topher, his and Angie’s son, who looks at me with the eyes of a very old soul as did his father.

My sweet Italian Mama, who always believed in her children regardless of obstacles, taught us that anything was possible; you just have to find the way and there is always a way to be found. Dad, now gone and terribly missed, was a Marine who gave me a strong sense of patriotism which translated (for me) into community service, an idea of giving back and learning that in giving I receive so much more than I could ever give. Sister Nonie, who is my second mama and also a writer, educated me in the ways of Suzy Homemaker and how (eventually) to stand up for any living creature in need, including myself. Finally and most dearly there is Gary, my sweet and loving husband, who can hug me and relieve any pain the world may heave upon these ever weary shoulders, a rock when my knees threaten to buckle, who holds me gently in his arms and keeps me safe. Most of us have someone in our lives to offer love and caring, even if our support systems are animals (like our uncharacteristically affectionate and attentive kitty, Izzy). Our supports offer friendship, love, a sense of presence in times of need, and refill our emotional tanks when those reserves threaten to run dry; they hold us up and sustain us when we cannot walk alone.

For all the EMTs, firefighters and police who have or are still working the road, you are my heroes. You are doing the best job that I have ever loved and I pray for you often. You are my family and we share a bond, even if we have never met, that cannot be explained or broken. Emergency Room staff, you and I stand together to bear the lunacy and sorrow, to fight our enemies (death, injury and illness) while trying to educate people and keep a sense of humor (as well as some level of empathy) intact. To you I say: keep your 16 gauge needles handy, remember the value of a B-52, and never, ever turn your back on a patient, however cooperative they were just a moment before. Keep your chins up, chests out, and remember that you do the impossible every day, in numbers no one could imagine, at a speed that rivals Olympic champions (regardless of your age, and the over-forty nurses especially will understand). Keep up the good fight, my brothers and sisters and hold each other up when it gets tough… we need to nurture that bond between us because no one, however much they see or read or witness, understands what we do. It is our private world, and this book will hopefully let outside folks see a little more of what we are made of and how we are trying to do the impossible every day, and win competitions where there is sometimes no clear winner. Most of all please continue to love what you do and if you don’t have the same passion you started with in emergency medicine, consider finding another avenue in which to channel your energies to keep your soul and your sanity intact.

When it is least expected, an Emergency Services worker can get “the call” that will change his life. We know that Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) is the way to appropriately handle emotionally traumatic types of circumstances and experiences we live through every day, so that we might keep our sanity and prevent becoming a second set of victims after witnessing trauma. Unfortunately, CISM is not practiced (or appropriately applied) everywhere and a lot of folks may be emotionally “lost” after a call that is so soul stirring they cannot mentally escape, causing the worker to become a secondary victim of the trauma himself. No one is immune.

This essay is about a medic who still carries an ambulance call clearly in her mind, heart and soul; although the emotional wounds have mostly healed, the memory remains and she is forever changed. “Angel” is now 26 years old with several years experience as an ER Tech in a Trauma Center; the medic became an ER nurse who worked with her daughter in that same hospital. Apparently, the apple doesn’t fall too far from the tree—what a legacy.

Sweet Dreams, Angel

The telephone’s ringing was an unwelcome intrusion into the night, breaking our silence into a thousand shards reflecting bits of dreams and pieces of reality mixing into an unreachable moment.

“Station nine, Cheryl,*” I mumbled, feigning coherence and attempting to ground myself in the moment and comprehend the directions I was about to be given.

“Priority one,” said Ronda,* the EMS dispatcher. “I need you on the air right away.”

I shook off the last remnants of sleep and called out to my partner in the bunk beside me. “Bob*: priority one. Ronda sounds a little edgy—we’d better move it.”

Sometimes the dispatchers have to use creative management skills when the crews on twenty-four hour shifts rebel at being allowed only a few minutes of sporadic and often interrupted sleep. Working a double, this had been one of those shifts; we were trying to grab a quick nap and hadn’t had time for lunch or dinner. Company policy dictated that we had three minutes to get into the ambulance and report on the air after being contacted by dispatch. Instead of using our time to freshen up, we each popped a piece of chewing gum into our mouths and immediately headed out the door. We assumed that Ronda was in a mood of some kind and didn’t want to incur any further wrath—we still had ten of the forty-eight hours left to work and alienating the affections of a dispatcher can never result in anything positive for EMS crew members.

“Alpha 255 is on the air.”

“255, priority one for Dearborn Park. Make northbound Southfield ramp to I-94 westbound. Child hit by a van. Your D-card number is 3472, time of call 2209h.”

“Alpha 255 copies that.”

We understood the edginess in Ronda’s formerly calm voice; the “big three” in dreaded EMS calls are those involving family members, friends and children. Normally I drove and Bob navigated, but this was a race against time. Bob jumped in the driver’s seat and I hopped into the back of the rig to set up the advanced life support equipment. We knew before we pulled the ambulance out of the bay that when a pedestrian takes on a motor vehicle, the vehicle usually wins.

“Spike two lines, normal saline and lactated ringers,” yelled Bob over his shoulder, straining to be heard above the screaming sirens. I knew what to do, but Bob’s calling out orders and my responding as I completed each step began the process of communication that was vital to our success as a team. “Pull out the drug box and set up the (cardiac) monitor. Don’t prepare the paddles or leads until we see how big this kid is.”

I hung the bags, though it seemed to take an interminable time; my hands felt big and especially clumsy as I tried to pull the packaging open and bleed the IV lines. The overhead strobe lights cast eerie red intermittent bursts inside the patient compartment, ticking off the seconds in our patient’s “golden hour.” It triggered an almost comical mental image of a wino, sitting in a cheap hotel room chain-smoking cigarettes with eyes transfixed on a small black-and-white TV screen. In this image, a red hotel sign flashed just outside his window, giving momentary peeks into the red, smoky glow of his reality. At that particular moment, my own reality was just as undesirable. I tried to free myself of those images and steered my mind back toward accomplishing the tasks at hand while taking a deep breath to reduce my anxiety and approaching panic.

“Both bags are hung, the tape is ripped and hanging on the overhead bar. Catheters are in a box on the bench seat with the pulse oximeter and the oxygen is on. Do you want the intubation kit left in the jump kit or opened and set up back here?”

“Leave it in the jump kit,” said Bob. “We might have to tube him on the ground.”

It was hard for me to monitor the radio communications from the back of the rig, so I asked Bob if the fire department was on scene: his response was a brusque, “Affirmative.” We knew that if fire-rescue workers were already there, they would stabilize our patient and perform whatever basic life support measures necessary. The fire trucks were a welcome sight as we rounded the curve toward the scene of the accident. My anxiety reduced slightly as I mentally checked off items in the victim stabilization process that I hoped would have been accomplished by the firefighters on scene, reducing our basic workload tremendously so that we could leap into the advanced trauma and life support steps that we hoped would make a difference in our patient’s chances for survival.

In that moment before stopping the rig and beginning our own tasks as paramedics, I switched to a more emotional appraisal of the situation. It isn’t our job to judge patients or their circumstances, but maintaining that particular level of professionalism is extremely difficult when you see something like severe trauma to a child. You can’t help wondering what prompted the child to be in such a dangerous place, especially at night… andwhere were his parents? Did they not care enough to monitor his whereabouts or bear any concern about his safety? Did they just assume that he had the appropriate judgment at his age to take care of himself?Somehow, I had switched into an empathetic mode for the child and anticipated the grief and loss that would be coming very shortly; in my own denial of the situation as it was announced by our dispatcher, I allowed a moment of anger to enter in before I even saw the boy’s face or condition. Inwardly, I prayed for this to be a salvageable situation where the boy may be injured but would live. We stopped the rig and the doors, pulled open by the firefighters, revealed a scene I had hoped not to see.

Looking at our patient, it didn’t seem like anyone would ever have the opportunity to question his judgment, or take away some privilege as punishment for his “playing in traffic.” The boy was obviously paying a pretty big price for what was probably an impulsive act. Instead of worrying about things that normally concern kids—like cool clothes, catching something awesome on the tube or getting the latest computer gadgetry—this kid was struggling to breathe.

The fire department rescue crew had already applied MAST pants to stabilize lower extremity fractures and secured our patient to a long backboard. He appeared about ten or eleven, blonde hair, about five feet tall, maybe 95 pounds. There were multiple abrasions on his head and face, matting his blonde hair into bloody clumps, with bruising around both eyes. Blood oozed out of the boy’s nose and mouth, staining the cervical collar placed by the firefighters around his neck. He was in labored, agonal respirations as we approached him.

Bob checked for pulses and found a faint radial pulse at a non-life sustaining rate of about thirty. The boy’s pupils were fixed and dilated, his skin cool and pale and his lungs were already filling with fluid. We popped an oral airway in his mouth and began bagging with 100% oxygen. Lifting him onto our stretcher, we welcomed him into our world: a guaranteed, miracle-making, emergency room on wheels, prayers administered copiously at no extra charge. Come one, come all, see the happy ending, just like on TV. No one dies; no one is permanently impaired and somehow, just before the final scene, the heavens open, music sounds, and all are made well.

After loading, we again checked for a heartbeat. Finding absent pulses and confirming that the boy was not breathing Bob muttered an expletive and called for CPR to begin as a firefighter jumped in the front seat of the ambulance to drive. While the firefighters on board continued compressions and bag-valve-mask ventilations, we got the intubation equipment ready. A “quick look” on the cardiac monitor showed an AMF rhythm (Adios, Mother F—r), also known as asystole—flat line. Firefighters continued CPR with hyperventilation while Bob intubated and I looked for a site to gain IV (intravenous) access. We knew the prognosis was not good, which only encouraged us to fight harder; neither of us was any good at accepting failure or at seeing a situation as impossible. We had the skills and the toys; somehow we would make it work… we had to, as defeat and loss were not acceptable options.

The firefighters had already cut the boy’s rather thick left coat sleeve. I assumed they had prepared an opening for me to start the IV line and I grabbed the boy’s arm with both hands to look for a good vein. The upper left arm bent quickly in half like a rag doll, mid-shaft. Apparently his humerus had sustained a complete fracture and the arm bent grotesquely and flopped off to the side. I shuddered, took a deep breath to decrease the nausea I immediately felt, grabbed my medic shears, and cut away the thick coat sleeve exposing the other arm. Finding an acceptable vein, I muttered an audible and brief prayer—something to the effect of, Dear God, please let me get this first try,—and popped a needle into his right antecubital vein. I taped the line down as Bob secured his endotracheal tube and started preparing the drugs while Bob established a second line in the boy’s left external jugular vein.

Things moved smoothly and efficiently, like a well-rehearsed movie scene, but it felt like an aberration of time to me as sounds and movements achieved a slowing distortion. Our on-scene and en route times would later prove exceptionally brief, but as we performed our duties it felt as though we were there for eons. Every thought and movement was muddled, feeling thick and expanded as one might view the world through the feverish eyes of illness. Despite perceptual conflicts, we did manage to get weak pulses back after pushing the epinephrine and atropine which gave us momentary hope to pull this child out of death’s clutches and hopefully back into his mother’s arms. As we worked against time and mortality, the monitor showed an ever-hopeful sinus tachycardia at a rate of 120, but it didn’t last.

During the call we pushed all of the appropriate drugs and performed our protocols flawlessly but the boy, whose name we later learned was Scott,* died shortly after arriving at the hospital. His skull exhibited profound crepitation and his abdomen was rigid and distended with spilled blood. My partner wrote the report as I cleaned our rig with Big Orange, a delightfully fresh aroma designed to replace the smell of blood and other spilled bodily fluids with a more socially acceptable citrus scent. When we had both finished, I went back into the room and held onto Scott’s cold foot for a moment, trying one last time to consciously will life back into him. Our training concentrates on producing positive results and saving lives; nobody ever told us what to do when our advanced skills and expensive toys don’t work. Nobody ever explained that you can be completely successful in applying all of your talents and still come out with the worst result. Nobody ever walked us through how to handle it emotionally when a child dies. Nobody seemed ever to be there to hold the hand of the medic feeling lost, hopeless and helpless as they watched the spirit of a child fade into the universe.

Bob and I didn’t talk about Scott, or the call, except to critique the procedures we performed. There was nothing we could have done additionally or differently, but the boy died. I reminded myself that God performs miracles in His time and on whom He decides to confer them. Scott just wasn’t to be a recipient. My partner and I finished our shift and without another word, went home.

I spent the next several hours cuddled up with my daughter. I phoned my son and told him I loved and missed him. The ambulance call, every detail perfectly preserved—a video without end—played itself continuously in my head reminiscent of a promotional loop. It was like a song that keeps repeating itself in your consciousness, getting louder and louder and you can’t escape from it regardless of how hard you try. My heart raced and I couldn’t take one of those deep, cleansing breaths that reduce stress to offer some measure of relief. There was no relief. There was no return to normalcy.

Sometimes, in a hidden corner of the mind, there exists a place removed from reality. Darkness and the images that saturate the senses reaffirm an individual’s powerlessness; these images are beyond the point of chosen exposure or experience. I spent the next 48 hours unable to eat or sleep, reliving the recent violation with its unrelenting intrusive thoughts following the trauma. As the second night filled with darkness devoid of mercy and the line between rational and irrational thought became a chasm leading to an emotional abyss, I reached out for help.

Mark D. is a good friend who holds a degree in psychology. When I called him, a friend of his answered the phone, telling me that Mark had just stepped out. “This is Cheryl. It’s nothing important, really, not a matter of life and death. Well, I guess it is about life and death, but it’s no big deal. Just tell Mark I said hi.”

He called back within minutes.

“What’s going on?”

“I had a bad call. We picked up a kid who had been FUBAR’d (F—d Up Beyond All Recognition) by a van. I don’t know what the deal is because I’ve been doing this for five years, and nothing has ever really bothered me before, but I can’t eat or sleep or turn it off and it just keeps rolling around in my head…”

“All right; first of all, I have a lot of respect for what you do. I could never do it. What you do and what you see out there are not the normal things that people see, or should see. Tell me what happened.”

Quickly relating the call in elaborate detail (with the images so firmly imprinted in my mind and heart that I could effortlessly rattle them off without stopping to breathe) I told Mark what happened. I still couldn’t catch my breath and the room seemed to swim as I visited that place again. My senses relived their experience: the smell of exhaust and blood, the bits of glass crunching under my boots, the controlled panic in the eyes of the emergency workers as they fought so desperately against death.

Feelings of inadequacy mounted, accompanied by the urgent desire to quit my job. I wanted to never have to go back, never face another parent who hands you their dead baby or have to wonder, as you race against time to a scene, what you will find. There was a wave of understanding beginning to flow over me. The medics with whom I’ve worked had told, in their most private moments, of a desire to have the power of God, just once, to re-inflate a soul with life in the middle of senseless tragedy. I had yearned for that power even if it meant just giving Scott’s parents the time to hold him and say goodbye before his body grew cold and lifeless. I had far more questions than answers, but couldn’t identify or speak them as my heart ached with this loss.

Mark listened patiently. After I had answered all of his questions, he asked the one that opened the door of my prison. “What was different about this call?” It took a few minutes to understand what he was asking. I had seen a lot of people in pieces, handled drowning victims, offered comfort and understanding to those who faced a loss of dignity and sanity. I’d received projectile vomitus, been perceived as a hero and then scorned, all in the same day. What was different about this particular call was not the call itself.

I was in the middle of some demanding personal problems. That same day, my (now) ex-husband had stormed out of the house, refusing to watch our ten-year-old daughter and leaving her to fend for herself. At work and away from home I was powerless to care for her and hoped that the neighbor she was visiting that day would see to her safety. I had assumed she was safe as she rode her bike with her friends down our quiet streets, but I couldn’t justify that assumption. There is no safe place, for her or for me. There is no special place where the boogie man is prohibited, where pain, sorrow and loss will not enter and change everything we’ve come to know, doing so in a way we could never imagine.

The anger at my situation and the realization of the parallel between the family of the dead child and my own became clear: Scott’s mother left him with relatives trusting that he would be all right and I was with this other mother’s child as he took his last breath and died before my eyes. Where was my child during this time? I remembered suppressing a horrible fear as I fought for Scott’s life: another medic may have been cutting my daughter’s coat sleeve, looking for a good vein, and trying to instill life into her lifeless form. Would they have mourned her loss? Would they be callous and marvel simply at how physical trauma can pull apart a human body without giving a thought to the soul within that battered body? Would they know she was a beautiful little girl who excelled in gymnastics, who played a trumpet, who delighted in decorating cakes with her mom and was a whiz at reciting Bible verses? Would they know what she would miss, what I would miss, in a future now denied her?

Mark let me see that I was crying for this dead child and for my own, for any pain in her life I couldn’t control, for any moment lost I couldn’t regain. I could feel Mark’s hand leading me gently out of the darkness of my self-imposed emotional prison. I cried for Scott and his family, prayed for their strength through each coming day, and felt a release as I let him go.

My daughter was upstairs in her bed, asleep. After hanging up the phone, I stood over my baby girl and just watched her for a while: her breathing was deep and even, her face as sweet and innocent as a newborn’s. Thanking God for her and for Mark’s wisdom and kindness, I climbed into her bed and wrapped my arms around her. Tucking her warm feet between mine and whispering, “Sweet dreams, Angel” into her ear, I drifted off to sleep.

~~~

As EMS professionals, there are some things we don’t discuss publicly, because the outside world just wouldn’t “get it” or might judge us as crude, callous, insensitive or uncaring in our disclosures. However, when your life is filled with blood, guts and gore, trauma and tragedy, insane hours without food, sleep or solace and you’re often treated like an “Ambulance (a.k.a Taxi) Driver” with no more skills or training than the fella who asks, “Would you like fries with that?” No offense, of course, to the fast-food employees who keep us alive. Sometimes we’ve just got to share the stuff that makes us giggle.

The following is a true story, as are all the essays in this book, but this is one of those “you had to be there” disclosures that I’m going to share even though you weren’t there because you may not see something like this on reality TV—and it bears telling. It is an example of the “gallows humor” that arises commonly with emergency services personnel in the light of traumatic situations (or where trauma is common in their professional walks). When we stop laughing, we cry, so finding a humorous moment in any situation is the key to our survival. Besides, you just can’t make this stuff up.

Cheap Date

In a very small town bordered by Lake Michigan,* everybody knew everybody and the town folks often wore multiple hats. For example, the Police Chief, “Jr,*” was the EMS Director/ Police Chief (Medical Examiner, local auctioneer, farmer and real estate agent) and police and EMS cohabitated in the same section in the rear of the City Hall building. Most police officers filled multiple and cooperative roles; police were Emergency Medical Technicians of varying licensure and the EMS service was housed within the police station. Since the building was very small and the “EMS Quarters” were in a miniscule room off the front desk of the police station (consisting of a bunk bed, small refrigerator, table and coffee pot shared by the police officers and EMS folks), there was no distance between the officers and EMTs, physically or emotionally.

In the PD/EMS community refrigerator, it wasn’t unusual to see a container of yogurt sitting apathetically next to a sealed box containing blood samples (drawn from a corpse after a fatal accident) held by the police chief/medical examiner as evidence before making its way to the county sheriff’s office. The shared bathroom had no shower, so those who put in 48 hour shifts learned to make do with what attempts at grooming and hygiene could be accomplished in the sink of that tiny bathroom (sink baths), another item to bring potential strangers to the level of family (albeit distant relatives) in a hurry. Most of the EMS staffers were volunteers who responded from home via pagers dispatched from the county seat several miles away, avoiding the need to “live in” during their shifts. Whether responding from home or the station, it was an exciting experience to work in this city teeming with lively characters and infinite stories, so whether the uniforms were police blue or EMS grey (or both in some cases), closeness and familiarity between the officers and medics was apparent.

Dispatch information for the county was often sketchy and guarded knowing that the radio calls were monitored by many of the folks within earshot of the tower that transmitted radio signals to police, fire and EMS. Since this was before September 11th changed everything, the dispatcher sent out ambulances for the entire county and many of the folks in the various cities, villages and boroughs owned VHF scanners to monitor these calls. Most of them kept a tablet next to the radio (to take notes) allowing locals to pass on accurate information to their neighbors. If they didn’t know the police “ten codes” by heart, they often had a cheat sheet under the scanner box for quick reference.

On one call, the primary county EMS unit (Alpha 93) was dispatched to a private address for an unknown “medical emergency.” Since the term medical emergency could mean anything from someone falling out of bed (sometimes needing only to be placed back into that bed by a couple pairs of strong hands) to a full arrest needing CPR and advanced life support, a police unit, ambulance, and several volunteer EMS personnel responded to the scene within minutes of each other.

Alpha 93 paramedics arrived to find a 54-year-old male, whom we’ll call Marcus* sitting on the toilet. Police arrived shortly thereafter and came in to find one paramedic, Roy,* standing next to the patient and the other, a female RN/Medic named Sasha* on her knees and with gloved hands closely examining the patient from the front. When the police officer, John, viewed the nature of the medical emergency, he quickly made eye contact with Roy* visually relaying, “I cannot believe what people do,” and did his best to stifle laughter, only letting go of a polite and forced cough or two, once turning his head to let his face relax for a moment before coming back into view of the patient and the rest of the crew.

Giving in to the strain of holding a straight face for an extended period, which was becoming painful as Officer John realized he was about to lose control and break out into the type of laughter that leaves one breathless and makes their sides ache, John excused himself and went to the front yard to redirect other EMS volunteers arriving from home. No further assistance was needed, everything was under control, move along. The patient was packaged onto the EMS stretcher with care and transported to the closest appropriate hospital, where a cursory report was given over the radio on the way, followed by a more detailed accounting to the medical staff face to face upon their arrival to the ER.

Apparently, the male patient had been pleasuring himself into a sample-sized bottle of shampoo and the bottle got stuck—two days earlier. Thinking that the situation would resolve itself, the man didn’t seek medical attention until the pain became excruciating. He was swollen to the point of almost engulfing the shampoo bottle with a purplish-red and fluid-filled hunk of flesh that was (and hopefully would be again) his penis.

In small towns, one incident is trumped by another and the talk of current runs and situations continued (EMS calls were discussed by the crews in strictly professional context, of course, during weekly continuing education sessions intending to increase their knowledge base and treatment options), so Marcus’ rendezvous with the shampoo bottle was quickly forgotten.

We responded to many interesting calls: the rescue in the woods near where migrant farm workers gathered of a woman who was chanting in tongues over an animal sacrifice and began seizing, the call where a man had gotten into a car accident and while the paramedics were delivering him to the ER his mother screamed at the medics for cutting away expensive clothing in an attempt to treat the patient’s life-threatening wounds, the gunshot at the local bar where a kid was cleaning a gun “to protect himself, as you never know who might come up from the city” and shot himself in the leg.

Meanwhile, back at the hospital, someone else took a side mirror off one of the ambulances—again—while backing into the ambulance bay, so would you please be careful. Lastly, no more squirting Medic Shawn through the open bunkroom window while he is asleep as he then has to respond to calls in a wet uniform, which is unprofessional. Oh… and please stop removing and hiding Shawn’s light bar from his POV (privately owned vehicle); if he wants to be Joe Medic, let him. So many runs (ambulance calls)… so much to learn.

Several weeks later, the EMS crew and police officers who had responded to Marcus’ all but forgotten call were walking down the street to the local café, “Mom’s Eats,*” and saw Marcus coming out of the local convenience store carrying a full-sized bottle of shampoo. The police chief, Jr (recalling the incident from which Marcus had apparently healed), couldn’t contain himself, as he looked in Marcus direction and remarked to the EMS crew (ever so casually but with an obvious glint in his eye) “Look… Marcus has a date!”

~~~

When the patient of an EMS call is a friend, family member or even the casual acquaintance of a rescuer, the experience for an Emergency Services (ES) Worker in responding to that call changes exponentially; this story is about Regan, the neighbor of several EMTs in a small mid-western town. Seeing bad things happen to children is the worst call an ES worker can imagine. Knowing them personally is unthinkable. This story is about one little girl who died too soon; the ES folks who were involved in her life and death won’t ever forget her.

Regan: Little Girl Lost

Regan* was ten when I first met her; flaming red hair, countless freckles and a shy reserve that made you want to pull her out of her highly-developed shell and introduce her to all the fun stuff in the world. A little overweight and terribly sensitive, Regan often hung around with my daughter, Elise,* who was only seven, but living three houses away made her a convenient “best” friend. Elise would invite Regan in not only to play, but to sample the Susie Homemaker type treats that were always found in our kitchen, and I remember Regan giggling at having a choice between any one or more of the delectable “from scratch” goodies that weren’t readily available in her own home. Coming from a family with two brothers, two parents and a deaf grandmother, Regan seemed happy enough with a quick smile and subdued laugh, but quite a loner without many friends. The last time I remember Regan visiting, it was because she had missed the bus and her mom was already gone for the day. “I don’t know what to do…” she’d said tearfully, and I told her not to worry, I’d drive her to school. If only all of life’s problems could be so easily solved.

At that time, so many years ago, I was mostly a stay-at-home mom who was also preparing to become a volunteer EMT. Toward that end, I had been issued the mandatory but goofy red, white and blue smock to wear on a “ride-along” (that blatantly identified me as a trainee) and issued a pager allowing me to be able to respond to calls from home, as I lived a mere two blocks from the ambulance bay. The smock was forgivable only because even without an EMT license, if you had the pager and smock you were respected as a medical professional by the townspeople who would hear the pager’s tones and dispatch information over the pagers and home scanners. If EMTs were in the middle of lunch at the local restaurant and had to run when the tones dispatched them to a call, those EMTs would often return to the restaurant later to find their meal packaged and ready for take-out. Respect comes in many forms and those small acknowledgments of personal value were a great perk to an often thankless job.

Being on-call as a third rider (the unlicensed third person on board the ambulance for any calls, an extra pair of hands in part of the “see one, do one, teach one” process), my uniform, boots and Trainee-Smock were at the ready and I became quite adept at going from sound asleep to fully dressed and in my car within one minute. If I was in a very deep sleep, that minute usually included about ten seconds of bouncing into doorways and walls while trying to orient myself to place and time. Later, I learned to snooze in a sleeping bag on top of the bed so if I was awakened from a deep sleep, I would know that if I was either on call for the volunteer service or at work for my city EMS job.

One night when the alarms went off, they weren’t just the tones from the radio dispatcher. The town sirens also rang out waking everyone within earshot; there was a fire somewhere and all emergency vehicles were to respond. On this particular night, I wasn’t on call to ride along, so when the town sirens beckoned, I pulled the pillow over my head and waited for them to stop. The tones had preceded the information given a few moments later that I couldn’t ignore: the fire was on the opposite side of my street and about three houses down. I pulled on my gear and walked rapidly—we are trained never to run—across the street and toward the fire.

The first thing I saw was a volunteer firefighter holding an oxygen mask over the face of the male homeowner. The mask had some misting to it, so I knew the man was still breathing and since the ambulances had not yet arrived, I assumed the firefighter had this patient under control and I walked toward the house to see if there was anything I could do there. Unable to get any closer than the front yard, I returned to the known victim, the dad, Gregg,* who was no longer breathing; as I prepared to start compressions, I asked the volunteer firefighter where he had the oxygen setting, following my mental checklist and wanting to assure that it was on “high flow.” The man answered that he didn’t know how to work the (oxygen) tank and I discovered that the oxygen was not yet turned on even though the mask had been on the patients face for several minutes. The oxygen was finally turned on to a high-flow setting, CPR was started on Gregg and he was packaged into ambulance number